Abstract

The kinetic parameters of absorption and distribution of ingested water (300 ml labeled with D2O; osmolality <20 mOsm kg−1) in the body water pool (BWP) and of its disappearance from this pool were estimated in 36 subjects from changes in plasma or urine deuterium to protium ratio (D/H) over 10 days using one- and two-compartment and a non-compartmental pharmacokinetic models (1-CM, 2-CM and N-CM which applied well to 58, 42 and 100% of the subjects, respectively). Compared with the volume and turnover of the BWP computed with the slope-intercept method (60.7 ± 4.1% body mass or 72.7 ± 3.2% lean body mass; turnover 4.58 ± 0.80 l day−1: i.e., complete renewal in ~50 days; n = 36), the values were accurately estimated with the N-CM and 1-CM and were slightly overestimated and underestimated, respectively, with the 2-CM (~7–8% difference, significant for water clearance only). Ingested water appeared in plasma and blood cells within 5 min and the half-life of absorption (~11–13 min) indicates a complete absorption within ~75–120 min. The 2-CM showed that in 42% of the subjects, ingested water quickly distributed within a central compartment before diffusing with a very short half-life (12.5 ± 4.3 min) to a peripheral compartment (18.5 ± 4.3 and 31.6 ± 6.4 L, respectively), which were in complete equilibrium within ~90 min. Pharmacokinetic analyses of water labeled with D2O can help describe water absorption and distribution, for which there is no well defined reference method and value; depending on the characteristics of the subjects and the drinks, and of environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Computation of the kinetic parameters of the body water pool (BWP) from the exponential decrease in urine deuterium to protium ratio (D/H) over a few days following D2O ingestion is a common procedure since it is a component of the doubly labeled water technique for measuring energy expenditure (Schoeller et al. 1986a; Westerterp et al. 1995). Changes in plasma D/H following ingestion of water labeled with D2O have also been described in several studies at rest or exercise [e.g., reviewed in the recent report by Armstrong et al. (2010)]. However, in these studies, most of the drinks, designed for endurance athletes, contained electrolytes and/or carbohydrates. There is, thus, a paucity of data on plasma D/H following ingestion of water with a low mineral content and without carbohydrate, although their consumption is encouraged in the general population (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products 2010). In addition, in these studies, with the exception of two conducted during exercise in the heat which describe the distribution of ingested water from the plasma to sweat (Armstrong et al. 2010; Koulmann et al. 1997), plasma D/H response following ingestion was mainly used to compare fluid “availability” or “delivery” from drinks with different compositions. As a consequence, no precise data are available on the kinetic of water absorption and distribution in the BWP.

The purpose of the present study was to estimate the kinetic parameters of the absorption and distribution of water with a low mineral content in the BWP and of its disappearance from this pool using D2O labeling and three pharmacokinetic models [one- and two-compartment (1-CM and 2-CM), and a non-compartmental model (N-CM)]. These models were applied to changes in plasma D/H over the first hour following ingestion of labeled water, and on changes in urine D/H over the nine following days. We hypothesized that the kinetic parameters of labeled water disappearance from the BWP and the turnover of this pool estimated with the pharmacokinetic models will be similar to the reference value computed over the 9 days following ingestion using the slope-intercept method applied to changes in urine D/H (Colley et al. 2007; Schoeller et al. 1986b). In contrast, there is no well-defined reference method for measuring the kinetic parameters of water absorption and distribution in the BWP and thus no reference value, which can be used to compare and validate those obtained with the three pharmacokinetic models. However, we hypothesized that these values will be consistent with the rate of gastric emptying (Lambert et al. 1997; Murray et al. 1994) and water absorption in the small intestine (Lambert et al. 1997; Lee et al. 1955; Love et al. 1968; Palma et al. 1981; Scholer and Code 1954) measured using perfusion techniques and with data concerning the disappearance from the circulation of labeled water administered in the blood (Edelman 1952; Maguire et al. 2003; Schloerb et al. 1950; Scholer 1962), its appearance in selected organs, tissues and body fluids in animals and in man (Armstrong et al. 2010; Bering 1952; Edelman 1952; Hahn and Hevesy 1940; Koulmann et al. 1997; Schwartz 1966) and its complete distribution in the BWP (Mendez et al. 1970; Schloerb et al. 1950; Schoeller et al. 1980; van Marken Lichtenbelt et al. 1994; Wong et al. 1988).

Methods

Subjects

The experiment was approved by the ethic committee of the Institut de recherches cliniques de Montréal and conducted on 36 young healthy male subjects who gave their written informed consent prior to taking part to the study. The subjects enrolled were lean and did not present any health problems likely to interfere with the variables studied, as judged from medical history, clinical examination, standard blood biochemistry and hematology. Additionally, the glomerular filtration rate was normal (Cockcroft and Gault 1976) (Table 1). Subjects had a normal circadian rhythm and ingested a normal mixed diet providing ~15, ~30, ~55% energy from protein, fat and carbohydrate, respectively, as assessed through an interview with a dietician. None of the subjects smoked, ingested more than two alcoholic drinks per day, engaged in regular training, or was taking any medication likely to interfere with digestive, metabolic or renal functions (e.g. diuretics, antiacids, etc.).

The waters ingested were six plain natural mineral waters with a low mineral content (osmolality <20 mOsmol kg−1), commercially available in Indonesia (Aqua®), Turkey (Hayat®), Spain (Lanjaron®), Argentina (Villavicencio®), France (Volvic®), and Poland (Zywiec-Zdroj®). Six subjects were randomly assigned to each of these waters.

Two days before ingesting the labeled waters, as well as over the nine subsequent days (day 1–9), the subjects refrained from exercising and ingesting alcohol and were allowed only three cups of coffee or tea per day. However, they were asked to drink ad libitum and to include in their beverages 2 l day−1 of the same water (average actual intake compiled from the daily logs = 1.97 ± 0.09 l day−1). Average urine specific gravity which was measured at day 0 and at the end of experiment was lower than the 1.02-cut-off value suggested by Oppliger et al. (2005) for a proper hydration (1.018 ± 0.004 and 1.014 ± 0.006 g ml−1, respectively; Atago refractometer, PAL-10S, Bellevue, WA, USA).

Labeled water ingestion and blood sampling

The water labeled with deuterium oxide (D2O) was ingested between 8:00 and 9:00 a.m. following an overnight fast. Subjects were first weighed and then asked to produce a urine sample (collection cup: VWR International, Ville-Mont-Royal, QC, Canada). A catheter (Protectiv Plus, Medex, Yellowknife, NT, Canada) was inserted in an antecubital vein for repeated blood sampling. Following a 10-min rest, a sample of saliva was collected (Salivette, Sarsdedt, Montreal, QC, Canada), an initial sample of blood (15 ml) was withdrawn (time 0), and the labeled water (300 ml) was ingested. For this purpose, the tracer (D2O: 0.10 g kg−1 lean body mass [LBM]; sterility tested, CIL, Andover, MA, USA, 99.8% D; actual dose given: 6.54 ± 0.76 g or 0.327 ± 0.038 mol) was mixed with 100 ml of the water. These first 100 ml were quickly ingested and two successive 100-ml volumes of the water were then, poured in the cup and quickly ingested in order to rinse the cup and wash down the tracer. The entire procedure took about 1 min. While the subject remained seated, 15-ml blood samples were withdrawn at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 and 60 min time points (K2EDTA, Becton–Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Between samplings, the catheter was kept patent using a heparin lock (100 IU heparin ml−1, Lock Flush, Hospira, Lake Forest, Ill, USA).

At the end of the 60-min observation period, the catheter was removed. The subjects were offered a breakfast and remained in the laboratory for an additional 60 min to monitor any discomfort or adverse events (none was observed).

Finally, the subjects provided urine samples first thing in the morning on days 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9. The exact time of sampling was recorded.

Measurement of D/H

The D/H in water from urine, saliva, plasma and blood cells was measured by mass spectrometry (see below). This measurement was made directly in saliva and urine, but water from the plasma and blood cells was partially purified before analysis. For this purpose, blood cells were first separated from plasma (3 min at 3,900×g within 2 min following sampling). After removal of the plasma, blood cells in the pellet were lysed by adding anhydrous KCl (12–15 mg ml−1 of blood cells), vortexed for 1 min and spun for 5 min at 3,900×g. Water in the plasma and in supernatant from the lysed cells was partially purified by centrifugation (30 min at 5,000×g, Amicon ultra 15, 10 kDa, NMWL, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

The D/H was analyzed on a Micromass Isoprime DI coupled with an Aquaprep system (Isoprime Ltd, Cheadle Hulme, UK) using the H2-water equilibration method in the presence of hydrophobic platinum as the catalyst (Horita and Kendall 2004). For this analysis, 200-μl samples were transferred into 3-ml vials (Labco Ltd, High Wycombe, UK) containing the platinum catalyst. After purging three times with hydrogen, the head space was filled with 2.8 ml of hydrogen and the deuterium in water was allowed to exchange and equilibrate with gaseous hydrogen by incubating 4 h at 40°C. A sample of the gas in the head space was directed into the isotope ratio mass spectrometer, dried through a cold trap (−80°C) and analyzed in Dual Inlet mode against an internal reference gas. Two internal reference waters were used to correct samples for drift and true isotope values during each analytical sequence. The internal reference waters were calibrated against V-SMOW (Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water) on the V-SMOW-SLAP (Standard light Antarctic Precipitation) scale. The D/H was expressed in ppm versus V-SMOW (155.76 ppm): D/H (ppm) = [(D/H in delta V-SMOW/1,000) + 1] × 155.76.

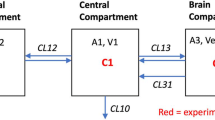

Kinetics of ingested water

The kinetics parameters of labeled water absorption and distribution in the BWP, and its disappearance from this pool were assessed using both compartmental models (1-CM with first-order absorption and elimination; 2-CM with first-order absorption and elimination from the central compartment) and a N-CM (WinNonlin Version 5.2 software; Pharsight Co., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). These three models were applied to plasma D/H from min 0 on day 0, to day 9, assuming that plasma D/H from day 1 to 9 was similar to that in urine (Schoeller et al. 1986a). The following parameters were computed: half-life of absorption (ta½, min), peak plasma D/H (C max, ppm) and time to reach C max (T max, min), area under plasma D/H concentration–time from 0 to infinity curve as a function of time (AUC0–∞, ppm day−1), volumes of distribution (total BWP with the three pharmacokinetic models: V, l), and central (V1, l) and peripheral volume (V2, l), rate constant of distribution (d, min−1) into V2 and td½ (with the 2-CM), water clearance (Clw, l day−1), half-life of water turnover (tr½, days), and mean residence time of water in the BWP (MRT, days). The volumes as well as Clw were corrected for exchange of deuterium with non-aqueous hydrogen (Racette et al. 1994).

The volume and renewal of the BWP were also modeled using the slope-intercept method (Colley et al. 2007; Schoeller et al. 1986b) from the decrease in urine D/H over the 9 days following ingestion of labeled waters (\( {\text{D}}/{\text{H}} = {\text{e}}^{{R_{0} - {\text{kr}} \times t}} \)). In this equation, \( {\text{e}}^{{R_{0} }} \) is the virtual D/H in the BWP at the time of ingestion, assuming an instantaneous and homogenous distribution of the complete dose of D2O administered in the BWP and kr is the rate constant of D2O disappearance from the BWP (which is equal to the rate of renewal of the BWP). The volume of the BWP was computed from \( {\text{e}}^{{R_{0} }} \) and the dose of D2O ingested taking into account the exchange of deuterium with non-aqueous hydrogen (Racette et al. 1994). The following kinetic parameters of the BWP were estimated: tr½ ([ln 2]/kr), MRT (1/kr) and Clw (BWP/MRT).

Statistics

Data are reported as mean and standard deviation. Comparisons were made with non-parametric (Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance for independent samples) or parametric methods (Student t tests and one- or two-way ANOVA for repeated or independent measurements) depending on the variable studied (see “Results”) using the Statistical Analyses System (SAS) software (v.9.1.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) at P < 0.05.

Results

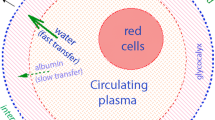

Background D/H before ingestion of labeled water in the 36 subjects ranged between 147 and 154 ppm and was not significantly different in urine, saliva, plasma or blood cells (149.0 ± 1.0, 149.1 ± 0.8, 148.8 ± 0.9 and 149.1 ± 1.4 ppm, one-way ANOVA for repeated measurements, P = 0.30). Following ingestion of labeled water, plasma and blood cell D/H quickly increased over basal values (Fig. 1). Both plasma and blood cell D/H were significantly above baseline values (see above) beginning at min 5: 192.8 ± 30.6 and 192.2 ± 30.8 ppm, respectively (Student t test for paired data, P < 0.0001); 95% confidence interval around the mean = 148–149 and 182–202 ppm for both plasma and blood cells at baseline and min 5, respectively. Individual D/H values in blood cells were remarkably similar to those observed in plasma (data not shown: mean difference ± SD = 0.8 ± 1.6 ppm, n = 252). Accordingly, the average value and dispersion of blood cell D/H were similar to the corresponding plasma values at all time points during the 60-min observation period [Fig. 1; two-way ANOVA for repeated measures (time × medium): no significant difference between media, P = 0.114]. Average peak plasma and blood cell D/H were reached at min 20, although individual time to peak ranged between min 15 and 60 (Fig. 2).

Plasma and blood cell deuterium to protium ratio (D/H) over the 60-min period following ingestion of labeled water (mean ± SD, n = 36). Blood samples were taken at min 0, 5, 10, 15 20, 30 and 60 but for the sake of clarity the data points for plasma and blood cell D/H have been slightly shifted to the left and right, respectively

No significant difference was present at any time point between the six groups of subjects for plasma and blood cell D/H during the 60-min period following water ingestion and for the corresponding kinetic parameters computed with the three pharmacokinetic models, respectively (Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance for independent samples; P > 0.05). The data obtained with the six waters were thus pooled for subsequent analysis.

Visual inspection of individual changes in plasma D/H following ingestion of labeled waters as well as examination of the goodness of fit with the compartmental models allowed segregating the 36 subjects into two groups (Fig. 2). In group 1 (n = 15, 42% of the subjects), plasma D/H peaked between min 15 and 30 (mean value = 326 ± 32 ppm observed at 20.0 ± 6.5 min) before decaying bi-exponentially and the data were well fitted by the 2-CM. In group 2 (n = 21, 58% of the subjects), plasma D/H peaked later, then decayed mono-exponentially and the data were well fitted by the 1-CM. In both groups, plasma D/H value was also well fitted by the non-compartmental model (N-CM). The goodness of fit of actual D/H values with predicted values yielded by the three pharmacokinetic models was assessed by the coefficient of variation, weighted corrected sum of squared observations, sum of weighted squared residuals, and weighted correlation coefficient between predicted and observed values (r > 0.93).

The decrease in urine D/H over the 9 days following ingestion of labeled water was adequately described by the slope-intercept method in each of the 36 subjects as shown by the correlation coefficients between predicted and observed values (r > 0.985, P < 0.0001) and no significant difference was observed between the two groups for any of the parameters (Table 2; one-way ANOVA for independent measurements, P > 0.15).

As depicted in Table 2, when compared with the kinetic parameters calculated with the 1-CM (group 2), the values of C max and T max calculated with the 2-CM (group 1) were higher and shorter, respectively (P < 0.001). The C max value computed using a compartmental model and the N-CM in the two groups was very similar. In group 1, the T max values predicted with the 2-CM and the N-CM were not different and close to that observed by visual inspection of the plasma D/H curve (~20 min). The T max value predicted by the N-CM in group 2 was much longer than that estimated in group 1 and much longer than that calculated with the 1-CM, and with a large inter-individual variability.

Based on the average values for ta½ estimated with the two-compartmental pharmacokinetic models (~11 and ~13 min with the 2-CM and 1-CM, respectively), water absorption was almost complete within ~75 to ~90 min after ingestion (i.e., 7 × ta½ with the 2-CM and 1-CM, respectively: >99% absorbed).

When the volume and kinetic parameters of the BWP estimated using the pharmacokinetic models were compared with those computed with the reference slope-intercept method in group 1, the 2-CM slightly but not significantly overestimated the volume of the BWP (e.g., ~3% for the absolute value and ~7% for the value corrected for LBM; not significant: one-way ANOVA for repeated measures, P = 0.40 and P = 0.19, respectively). The turnover of the BWP was, thus, slightly but significantly underestimated (e.g., ~8% for Clw; P = 0.041). In contrast, in group 2, no significant difference was observed between the volume and the kinetic parameters of the BWP obtained with the three models (one-way ANOVA for repeated measures; P > 0.52).

As shown in Fig. 3, for group 1, the volume of the central compartment computed using the 2-CM [18.5 ± 4.3 l, corresponding to 37 ± 10% of the total BWP and including the blood (~6 l in 76.9-kg subjects) but also a portion of extra-vascular space] was smaller than that of the peripheral compartment (31.6 ± 6.4 l or 63 ± 10% of the BWP). The microconstants depicted in Fig. 3 show that the rate constant of absorption was much greater than the inter-compartmental transfer constants and the elimination rate constant. The half-life of water distribution between the central and peripheral compartment (td½) was estimated to be 12.5 ± 4.3 min, indicating that ~90 min after ingestion, labeled water was almost evenly distributed within the entire BWP (>99% of the pool).

Mean kinetic parameters within a two compartment model and volume of the central (V1) and peripheral compartment (V2) (mean ± SD). ka rate constant of water absorption in the central compartment; k12 and k21 rate constant of water transfer between V1 and V2, and V2 and V1; kel rate constant of elimination from the central and peripheral compartments (kel1 and kel2, respectively)

Discussion

The purpose of the present experiment was to describe the kinetic parameters of water absorption and distribution in the BWP and the volume and turnover of this pool using pharmacokinetic models applied to changes in plasma D/H in the 60-min period following labeled water ingestion and in urine D/H over the nine following days.

Size and turnover of the BWP

Wang et al. (1999) showed that in adult mammals, including humans, hydration of fat free mass is relatively stable at ~73%. The volume of the BWP computed with the reference slope-intercept method in the present experiment for the 36 subjects (46.6 ± 5.7 l or 60.7 ± 4.1% body mass [BM] and 72.7 ± 3.2% LBM) is in complete accordance with this constant. The turnover of the BWP computed with the slope-intercept method (4.58 ± 0.80 l day−1, n = 36) was slightly higher than that reported in adult male subjects (~3.2–3.7 l day−1) [e.g., Blanc et al. (1998), Leiper et al. (1996), Raman et al. (2004), and Schoeller et al. (1986b)]. However, this may simply be due to the fact that the subjects were requested to drink 2 l of water day−1. Assuming that renal clearance is responsible for ~60% of water elimination (Raman et al. 2004) (vs. 40% in expired gas, sweat and feces), urine production can be estimated to ~2 ml min−1 or as expected, ~2% of the glomerular filtration rate estimated from the clearance of creatinine (110 ml min−1; see Table 1). The comparatively high water turnover observed translated into a renewal of the BWP (tr½ = 6.88 to 7.5 days; a higher value was observed with the 2-CM because of the larger volume estimated), which was slightly faster than generally observed in young subjects with a normal BM and a high BWP (7.17 ± 1.03 vs. 8–9 days) (Blanc et al. 1998; Leiper et al. 1996; Schoeller et al. 1986b). According to the value of tr½, the MRT of ingested water in the BWP was 10.3 ± 1.5 days which indicates that it will take ~50 days for complete elimination (i.e., >99%) of the ingested water and to renew the BWP.

The 2-CM slightly overestimated the volume of the BWP and slightly underestimated its turnover. In contrast, the volume and turnover of the BWP estimated with the N-CM (groups 1 and 2) and with the 1-CM (group 2) were within 0–2% of the corresponding values computed with the reference slope-intercept method.

Taken together, these data show that, when compared to the reference values computed with the slope-intercept method, the pharmacokinetic analysis performed in the present experiment provided very good estimates of the size and turnover of the BWP for all subjects using a N-CM pharmacokinetic model and with subjects in group 2 with the 1-CM. However, the values obtained with the 2-CM model for subjects in group 1 differed slightly from the reference data.

Water absorption

Water absorption was very rapid: plasma D/H was significantly above background as soon as 5 min after ingestion and peaked at min ~20; the ta½ calculated with the two compartmental pharmacokinetic models was ~11–13 min (this parameter is not estimated with the N-CM). These values are well in line with data from studies which have described changes in plasma D/H following ingestion of labeled water at rest with a high sampling rate (Currell et al. 2008; Davis et al. 1987, 1990): the tracer ingested was present in plasma as soon as 2–2.5 min following ingestion and the value of ta½ computed using a simple exponential model (Currell et al. 2008) or which can be estimated from visual inspection of the curves (Davis et al. 1987, 1990) ranged between 9.5 and 12 min. Based on the value of ta½ computed in the present study, ~99% of the 300 ml of water ingested were absorbed in ~75–90 min (i.e., 7 × ta½) or an average absorption rate of ~3.3–4 ml min−1. This is well below the maximal rate of gastric emptying and water absorption in the small intestine [~20–25 ml min−1 (Lambert et al. 1997; Murray et al. 1994) and 12–15 ml min−1, respectively (Lambert et al. 1997; Lee et al. 1955; Love et al. 1968; Palma et al. 1981; Scholer and Code 1954)] and is consistent with the concept that with 300 ml ingested, the kinetics of water absorption are first-order.

An interesting observation is that in most subjects (~58%, group 2), ingested water had a rapid unrestricted access to the entire BWP (45.7 ± 3.1 l or 61.2 ± 7.7% BM, not significantly different from the values computed with the reference slope-intercept method: 45.3 ± 4.6 l and 60.3 ± 4.6% BM; one-way ANOVA for repeated measures, P = 0.89 and 0.56, respectively). The kinetic parameters estimated with the 1-CM indicate that the absorption of water and its distribution in the BWP were complete within 75 min to 2 h following ingestion. In contrast, in the remaining ~42% of the subjects (group 1) ingested water was rapidly distributed within a 18.5-l central compartment before diffusing in a 36-l peripheral compartment. The central compartment included the blood (plasma and blood cells which are in continuity: see below) but also a large portion of the extra-vascular space and the total volume of distribution (i.e., central plus peripheral compartments) was not significantly different than the volume of the total BWP computed with the reference slope-intercept method (see above). The distribution rate constant describing water exchanges between the central and peripheral compartment estimated with the 2-CM (d = 18 ± 6 min) showed that water left the central compartment with a very short half-life (td½ = 12.5 ± 4.3 min, i.e., only slightly longer than the ta½ estimated with the 2-CM). Accordingly, the distribution of water in the BWP was also complete ~90 min following ingestion.

Except for a brief mention by Schloerb et al. (1950), we are not aware of any study discussing that, after ingestion of water labeled with D2O, plasma D/H can follow two different patterns and that in some subjects the water ingested rapidly distributes in a central compartment before diffusing with a small delay in the entire BWP. However, this phenomenon can be suspected from results of several previous studies in which, following ingestion of water labeled with deuterium (Armstrong et al. 2010; Currell et al. 2008; Davies et al. 2001; Hill et al. 2008; Schloerb et al. 1950) or tritium (Pinson and Langham 1957), the pattern of tracer-to-tracee ratio in plasma (Armstrong et al. 2010; Currell et al. 2008; Pinson and Langham 1957; Schloerb et al. 1950), saliva (Hill et al. 2008) or breath water (Davies et al. 2001) was similar to that observed in group 1 in the present experiment; at least in some subjects. This pattern indicates that in some subjects the rate of water absorption from the gut exceeded the rate of water distribution in the BWP. Since the time needed for a complete distribution of ingested water within the entire BWP was not shorter in group 1 than in group 2 (~90 vs. ~75–120 min) it can be suggested that the difference between the pattern of blood D/H between the two groups was due to a slightly higher rate of water absorption in the blood in group 1, which in turn could be due to a higher rate of gastric emptying and/or water absorption in the small intestine. Although the difference was not statistically significant, ta½ was actually slightly smaller in group 1 than 2 (10.9 ± 3.6 vs. 12.9 ± 7.0 min, Student t test for independent sample, P = 0.16).

The minimum time needed for a complete isotopic equilibrium between ingested water and the BWP has been investigated and discussed by several authors (Mendez et al. 1970; Schloerb et al. 1950; Schoeller et al. 1980; van Marken Lichtenbelt et al. 1994; Wong et al. 1988) because it is a key point to consider when computing the volume of the BWP by tracer techniques. Based on the stability of the tracer-to-tracee ratio in body fluids (as well as in breath CO2 for 18O), data from these studies suggest that an isotopic equilibrium is reached between 1 and 4 h. Results from the present study based on estimates of the kinetic parameters of water absorption and distribution are well in line with this range of values: depending on the model which best fitted the data points, within ~75 to 120 min ingested water was completely absorbed and evenly distributed in the entire BWP in both groups.

Kinetic of distribution of ingested water in selected organs and tissues

Because of both technical and ethical limitations, there are limited data on the kinetic of the distribution of ingested water in various sub-compartments of the BWP in humans and animals. In the present experiment, the similar D/H values observed in plasma and blood cells are well in line with in vitro data showing that the time needed for equilibration between extracellular tritiated water and water in red blood cells is only a few milliseconds (Fabry and Eisenstadt 1975). However, ingested water rapidly distributed outside the vascular compartment in both groups. This observation is consistent with data showing that water exchanges between plasma and interstitial fluids across capillary beds are several orders of magnitude larger than plasma flow (Pappenheimer 1953) and that exchanges of water between interstitial and intra-cellular water is also very rapid (Bacic et al. 1989; Verkman and Wong 1987). It is also consistent with a limited number of data obtained in man, showing that D2O administered in bolus in a peripheral vein disappears from the blood with a ~2–3 min half-life (Edelman 1952; Schloerb et al. 1950; Scholer 1962) and within 1 min is distributed in a volume corresponding to ~20% BM (Edelman 1952). A recent pharmacokinetic analysis of H2 15O disappearance from the blood following rapid administration in a peripheral vein shows that in man, the tracer was distributed within 3 min in a 20- to 22-l volume (Maguire et al. 2003) (~30% BM in the 70-kg subjects studied); a value which is close to the volume of the central compartment estimated in the present experiment. Data obtained in man and animals (Bering 1952; Edelman 1952; Hahn and Hevesy 1940; Schloerb et al. 1950; Schwartz 1966) suggest that the central compartment probably corresponds to water (interstitial fluids and intra-cellular water) in well perfused organs and tissues such as the brain (Bering 1952), liver (Edelman 1952), kidney (Schwartz 1966) and spleen (Schwartz 1966), in which the tracer/tracee ratio equilibrates with that in blood within ~2–10 min. It can be suspected also that during exercise in the heat, the skin, with a high blood flow, belongs to the central compartment. Data from Koulmann et al. (1997) indeed show that D/H in sweat collected over 30-min periods was similar to the corresponding average value in plasma. Recent data by Armstrong et al. (2010) confirm that D2O appeared in sweat within 10 min after ingestion but sweat D/H was consistently lower than plasma D/H over the entire 60-min period of exercise. As for the peripheral compartment, it probably corresponds to water in organs and tissues with lower perfusion and to water compartments with a low rate of renewal in which the tracer/tracee equilibrates more slowly with that in blood such as the skeletal muscles at rest (~10–40 min) (Schwartz 1966), the cerebrospinal fluid (~60 to 150 min) (Bering 1952; Schloerb et al. 1950) and bones (~4 h) (Edelman 1952).

Conclusions

Results from the present experiment show that when compared to the values computed with the reference slope-intercept method, the size and turnover of the BWP were accurately estimated: (1) using the N-CM in all the subjects studied, and (2) with the 1-CM pharmacokinetic model with first order absorption and elimination, in almost 60% of the subjects. In the remaining ~40% of the subjects, the data were best fitted with the 2-CM and the size of the BWP was slightly overestimated, with its turnover slightly underestimated. It should be recognized that, from a practical point of view, there are no advantages to estimate the size and turnover of the BWP using pharmacokinetic models when these data can be easily computed using the simple slope-intercept method. The main benefit of the pharmacokinetic analyses is to provide estimates of the kinetic parameters of water ingestion and distribution in the BWP, for which there are currently no well-defined reference values. Obviously, the values obtained depend on the model used, and the validity of pharmacokinetic models applied to water absorption and distribution will have to be further verified. In this respect, one limitation from the present study is the absence of data points between min 60 following ingestion and the next morning, at a time when isotopic equilibration occurs. These data points could help improve the kinetic parameters estimated with the 2-CM, which are slightly different from the reference values. Future researches could also focus on day-to-day intra-individual reproducibility of plasma D/H response and the kinetic parameters of water absorption and distribution following labeled water ingestion, for which, except for a short comment by Davis et al. (1987) no data are currently available. These reference data are needed to further describe possible changes in the kinetic parameters of water absorption and distribution in the BWP depending on the characteristics of the drinks (e.g., volume, temperature, electrolyte and carbohydrate content, etc.), of the subjects (e.g., age, hydration state, disturbances in gastro-intestinal functions, etc.) and of environmental conditions (e.g., rest vs. exercise, heat vs. cold, etc.).

Ethical standard The experiment was performed in compliance with laws of Canada.

References

Armstrong LE, Klau JF, Ganio MS, McDermott BP, Yeargin SW, Lee EC, Maresh CM (2010) Accumulation of 2H2O in plasma and eccrine sweat during exercise-heat stress. Eur J Appl Physiol 108:477–482

Bacic G, Alameda JC Jr, Iannone A, Magin RL, Swartz HM (1989) NMR study of water exchange across the hepatocyte membrane. Magn Reson Imaging 7:411–416

Bering EA Jr (1952) Water exchange of central nervous system and cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurosurg 9:275–287

Blanc S, Normand S, Ritz P, Pachiaudi C, Vico L, Gharib C, Gauquelin-Koch G (1998) Energy and water metabolism, body composition, and hormonal changes induced by 42 days of enforced inactivity and simulated weightlessness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:4289–4297

Cockcroft DW, Gault MH (1976) Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 16:31–41

Colley RC, Byrne NM, Hills AP (2007) Implications of the variability in time to isotopic equilibrium in the deuterium dilution technique. Eur J Clin Nutr 61:1250–1255

Currell K, Urch J, Cerri E, Jentjens RL, Blannin AK, Jeukendrup AE (2008) Plasma deuterium oxide accumulation following ingestion of different carbohydrate beverages. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 33:1067–1072

Davies S, Spanel P, Smith D (2001) Rapid measurement of deuterium content of breath following oral ingestion to determine body water. Physiol Meas 22:651–659

Davis JM, Lamb DR, Burgess WA, Bartoli WP (1987) Accumulation of deuterium oxide in body fluids after ingestion of D2O-labeled beverages. J Appl Physiol 63:2060–2066

Davis JM, Burgess WA, Slentz CA, Bartoli WP (1990) Fluid availability of sports drinks differing in carbohydrate type and concentration. Am J Clin Nutr 51:1054–1057

Edelman IS (1952) Exchange of water between blood and tissues; characteristics of deuterium oxide equilibration in body water. Am J Physiol 171:279–296

EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products N, and Allergies (NDA) (2010) Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for water. EFSA J 8:48

Fabry ME, Eisenstadt M (1975) Water exchange between red cells and plasma. Measurement by nuclear magnetic relaxation. Biophys J 15:1101–1110

Hahn L, Hevesy G (1940) Rate of penetration of ions through the capillary wall. Acta Physiol Scand 1:347–361

Hill RJ, Bluck LJ, Davies PS (2008) The hydration ability of three commercially available sports drinks and water. J Sci Med Sport 11:116–123

Horita J, Kendall C (2004) Stable isotope analysis of water and aqueous solutions by conventional dual-inlet mass spectrometry. Handbook of stable isotope analytical techniques, vol 1. Elsevier, New-York, pp 1–37

Koulmann N, Melin B, Jimenez C, Charpenet A, Savourey G, Bittel J (1997) Effects of different carbohydrate-electrolyte beverages on the appearance of ingested deuterium in body fluids during moderate exercise by humans in the heat. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 75:525–531

Lambert GP, Chang RT, Xia T, Summers RW, Gisolfi CV (1997) Absorption from different intestinal segments during exercise. J Appl Physiol 83:204–212

Lee PR, Code CF, Scholer JF (1955) The influence of varying concentrations of sodium chloride on the rate of absorption of water from the stomach and small bowel of human beings. Gastroenterology 29:1008–1016

Leiper JB, Carnie A, Maughan RJ (1996) Water turnover rates in sedentary and exercising middle aged men. Br J Sports Med 30:24–26

Love AH, Mitchell TG, Phillips RA (1968) Water and sodium absorption in the human intestine. J Physiol 195:133–140

Maguire RP, Spyrou NM, Leenders KL (2003) Whole body [O-15] water pharmacokinetics measured in blood. Physiol Meas 24:237–249

Mendez J, Prokop E, Picon-Reategui E, Akers R, Buskirk ER (1970) Total body water by D2O dilution using saliva samples and gas chromatography. J Appl Physiol 28:354–357

Murray R, Eddy DE, Bartoli WP, Paul GL (1994) Gastric emptying of water and isocaloric carbohydrate solutions consumed at rest. Med Sci Sports Exerc 26:725–732

Oppliger RA, Magnes SA, Popowski LA, Gisolfi CV (2005) Accuracy of urine specific gravity and osmolality as indicators of hydration status. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 15:236–251

Palma R, Vidon N, Bernier JJ (1981) Maximal capacity for fluid absorption in human bowel. Dig Dis Sci 26:6

Pappenheimer JR (1953) Passage of molecules through capillary walls. Physiol Rev 33:387–423

Pinson EA, Langham WH (1957) Physiology and toxicology of tritium in man. J Appl Physiol 10:108–126

Racette SB, Schoeller DA, Luke AH, Shay K, Hnilicka J, Kushner RF (1994) Relative dilution spaces of 2H- and 18O-labeled water in humans. Am J Physiol 267:E585–E590

Raman A, Schoeller DA, Subar AF, Troiano RP, Schatzkin A, Harris T, Bauer D, Bingham SA, Everhart JE, Newman AB, Tylavsky FA (2004) Water turnover in 458 American adults 40–79 yr of age. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286:F394–F401

Schloerb PR, Friis-Hansen BJ, Edelman IS, Solomon AK, Moore FD (1950) The measurement of total body water in the human subject by deuterium oxide dilution; with a consideration of the dynamics of deuterium distribution. J Clin Invest 29:1296–1310

Schoeller DA, van Santen E, Peterson DW, Dietz W, Jaspan J, Klein PD (1980) Total body water measurement in humans with 18O and 2H labeled water. Am J Clin Nutr 33:2686–2693

Schoeller DA, Leitch CA, Brown C (1986a) Doubly labeled water method: in vivo oxygen and hydrogen isotope fractionation. Am J Physiol 251:R1137–R1143

Schoeller DA, Ravussin E, Schutz Y, Acheson KJ, Baertschi P, Jequier E (1986b) Energy expenditure by doubly labeled water: validation in humans and proposed calculation. Am J Physiol 250:R823–R830

Scholer JF (1962) Determination of rates of absorption in the blood by integration of rates of appearance and disappearance. Am J Dig Dis 7:43–49

Scholer JF, Code CF (1954) Rate of absorption of water from stomach and small bowel of human beings. Gastroenterology 27:565–583

Schwartz PL (1966) Exchange of blood water in normal tissues and mammary carcinomas in mice. Am J Physiol 211:173–176

van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Westerterp KR, Wouters L (1994) Deuterium dilution as a method for determining total body water: effect of test protocol and sampling time. Br J Nutr 72:491–497

Verkman AS, Wong KR (1987) Proton nuclear magnetic resonance measurement of diffusional water permeability in suspended renal proximal tubules. Biophys J 51:717–723

Wang Z, Deurenberg P, Wang W, Pietrobelli A, Baumgartner RN, Heymsfield SB (1999) Hydration of fat-free body mass: review and critique of a classic body-composition constant. Am J Clin Nutr 69:833–841

Westerterp KR, Wouters L, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD (1995) The Maastricht protocol for the measurement of body composition and energy expenditure with labeled water. Obes Res 3(Suppl 1):49–57

Wong WW, Cochran WJ, Klish WJ, Smith EO, Lee LS, Klein PD (1988) In vivo isotope-fractionation factors and the measurement of deuterium- and oxygen-18-dilution spaces from plasma, urine, saliva, respiratory water vapor, and carbon dioxide. Am J Clin Nutr 47:1–6

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jean-François Hélie, Ph.D. from the Laboratoire de Géochimie des isotopes stables (Centre GEOTOP-UQAM) for performing the D/H assays. The study was supported by a grant from DANONE Research.

Conflict of interest

Rémi Rabasa-Lhoret, Diane Mignault and Patrick du Souich do not have any conflict of interest. François Péronnet is an occasional consultant for DANONE Research. Sébastien Vergne, Laurent Le Bellego and Liliana Jimenez are employees of DANONE Research.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Susan A. Ward.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Péronnet, F., Mignault, D., du Souich, P. et al. Pharmacokinetic analysis of absorption, distribution and disappearance of ingested water labeled with D2O in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 112, 2213–2222 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-011-2194-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-011-2194-7