Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether gender-segregated occupations and branches are associated with future medically certified sick leave for women and men.

Methods

All gainfully employed residents in Sweden in December 31st 2014 aged 16–69 years (n = 4 473 964) were identified in national registers. Subjects working in segregated (61–90%) and extremely segregated (> 90%) occupations and branches were evaluated v/s subjects in gender-integrated occupations and branches (40–60%). Combinations of segregation by occupation and branch were also investigated. Two-year prospective medically certified sick leaves (> 14 days) were evaluated using logistic regression with odds ratios recalculated to relative risks (RR), adjusted for work, demographic and health related factors.

Results

The sick leave risk was higher for those working in extremely female-dominated occupations (women RR 1.06 and men RR 1.13), and in extremely female-dominated branches (women RR 1.09 and men RR 1.12), and for men in extremely male-dominated branches (RR 1.04). The sick leave risk was also higher for both women and men in female-dominated occupations regardless of the gender segregation in the branch they were working in. However, the differences in sick leave risks associated with gender segregation were considerably smaller than the differences between occupations and branches in general.

Conclusions

Gender segregation in occupations and branches play a role for sick leave among women and men, especially within extremely female-dominated occupations and branches. However, gender segregation appears to be subordinate to particular occupational hazards faced in diverse occupations and branches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Why is gender segregation problematic for occupational health?

Gender segregation at workplaces are often problematized in terms of the mental strain put on persons in minority positions (Evans and Steptoe 2002; Kanter 1977), potentially reducing their ability to work and increase their sick leave (Alexanderson et al. 1994; Leijon et al. 2004). Still, other studies give no support for higher sick leave in the minority group (Mastekaasa 2005), or report higher psychological stress among those working at gender balanced workplaces (Elwer et al. 2014). There may also be a gender difference as regards minority status. Men may be more welcome in female-dominated occupations than the other way around, as bearers of potential status to the occupation (Kröger 2017; Jonsson et al. 2013).

The presence of so-called absence cultures, with more permissive attitudes towards work absence, has also been reported in the literature (Laaksonen et al. 2012; Nicholson and Johns 1985; Virtanen et al. 2000). However, in women-dominated occupations and workplaces among Helsinki town employees, such cultures have been attributed to self-certified short-term sick leave rather than medically certified long-term sick leave (Laaksonen et al. 2012). More tolerant sick leave attitudes in extremely gender-segregated occupations have also been reported in a recent Norwegian study, but no differences in attitudes were found between women and men (Löset et al. 2018), contesting the role of gendered sick leave attitudes per se.

A competing explanation suggests that the increased risk for sick leave among employees in female-dominated occupations and workplaces is due to a poor psychosocial work environment (Elwer et al. 2014; Lidwall et al. 2018; Wieclaw et al. 2006). Furthermore, in female-dominated workplaces within health care and social care, treatments are often more available and the acceptance for weakness and health impairments is higher (Wieclaw et al. 2006). In addition, health selection potentially influences the association at different parts of the labour market (Grönlund and Magnusson 2018; Hensing and Alexanderson 2004; Kröger 2016; Melsom and Mastekaasa 2019; Milner et al. 2018). In the Swedish context, it has also been reported that workplaces with higher sick leave rates tend to recruit labour with sick leave in their work history (Nordström et al. 2016).

The operationalisation of gender segregation

The concept of workplace is seldom problematized in the literature regarding workplace gender segregation and health. In studies of single organisations, branches or occupations, the concept of workplace is fairly straightforward (Hensing and Alexanderson 2004; Laaksonen 2012). But in studies with heterogeneous samples or entire labour markets, the concept of workplace is problematic and for practical reasons researchers often operationalize workplace gender composition using occupational gender composition (Gonäs et al. 2019; Hensing and Alexanderson 2004; Leijon et al. 2004; Melsom and Mastekaasa 2018; Milner et al. 2018; Nyberg et al. 2018).

Occupational working conditions and the contextual factor of branch

Another feature of the literature regarding gender segregation and sick leave is that other working conditions than gender segregation are often overlooked, (Gonäs et al. 2019; Laaksonen et al. 2012; Melsom and Mastekaasa 2018) which is problematic because gender segregation and adverse working conditions often coincide (Elwer et al. 2014; Lidwall et al. 2018; Wieclaw et al. 2006). An extensive review of sick leave research also highlighted that the lack of adjustment for occupation in studies analysing the role of working conditions is problematic, especially in studies investigating occupationally heterogenous populations (Allebeck and Mastekaasa 2004). However, some later studies adjust for occupation (Mastekaasa 2005; Nordström et al. 2016) or distinct aspects of the work environment (Bryngelson et al. 2011; Hensing and Alexanderson 2004; Jonsson et al. 2013). Indeed, occupation is a potent factor for worker health encompassing both occupational and socioeconomic conditions playing a crucial role for differences in sick leave (Lidwall et al. 2018; Mastekaasa 2005; Virtanen et al. 2010). As employers have a key role in addressing preventive work environment measures, branches are also crucial for the identification of where to intervene (Berglund et al. 2019; Gaspar et al. 2018; Irastorza et al. 2016; Kristman et al. 2016; Marshall et al. 1997). Branch is also an important contextual factor constituting economic conditions and future prospects influencing wages, job opportunities and job security (Irastorza et al. 2016; Kristman et al. 2016; Marshall et al. 1997; Virtanen et al. 2010). Branch may also be a relevant indicator of the gendered labour market, where a gender minority position may be protected as long as one is adhering to traditional gender norms, i.e. women sticking to female occupations within male branches and men sticking to male occupations within female branches (Swedish social insurance agency 2018). Such mechanisms may also explain why the gender minority hypothesis originally presented by Kanter in 1977 has received so limited empirical support in studies using occupational gender segregation.

To account for gender aspects of both the work tasks one performs and the broader work environment and economic context, the present study operationalise gender composition by addressing gender segregation within both occupations and branches, and their combinations. The study simultaneously adjusts for the role of other working conditions, using occupation and branch at a more aggregated level as approximate covariates. With sick leave as the outcome, this has not been done before for a country’s entire working population.

Aim

To investigate whether working in gender-segregated or gender-integrated occupations and branches and their combinations is associated with future medically certified sick leave for women and men. First, in accordance with the literature, U-shaped risk distributions with high sick leave risks in either female- or male-dominated occupations and branches are expected. Second, for combinations of gender segregation in occupations and branches, it is expected that sick leave risks are higher in lower status, adverse working conditions female occupations and branches, especially among men. The latter hypothesis is due to prevailing norms of proper gender behaviour and the negative attention towards breaking such norms, especially for men, and the lower status attached to female-dominated branches and occupations.

Methods

Study population

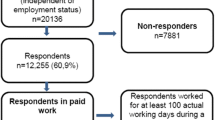

The population at risk, i.e. the employed residents in Sweden in ages 16–69 years the 31st of December 2014 were identified in the registers maintained by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SSIA) and their subsequent sick leave during the two-year follow-up in 2015 and 2016. In all 4, 510, 988 persons were identified as employed. After exclusion of individuals who emigrated (37, 024) or died (14, 185) during follow-up, the population eligible for analysis consisted of 4, 473, 964 persons.

Measures

Exposures—gender segregation in occupations and branches

The exposures where measured at the most feasible level of detail. Occupation was measured according to the Swedish version of ISCO-88, Swedish Standard Classification of Occupations (Statistics Sweden 2001), at the four-digit level constituting detailed unit occupational groups. Branches were measured according to the Swedish version of NACE rev 2, Swedish Standard Industrial Classification (Statistics Sweden 2007), at the three-digit level constituting detailed branch groups. The data originally contained 355 occupations and 265 branches. They were reduced to 299 occupations and 213 branches when categories with less than 1,000 employees were merged into larger groups described elsewhere (Swedish Social Insurance Agency 2018). For the 299 occupations and 213 branches, the measure of gender segregation is the proportion of women in each of these occupations and branches. Gender segregation was classified in five categories: extremely female dominated > 90%; female dominated 61–90%; integrated 40–60%; male dominated 61–90% and extremely male dominated > 90%. The distributions for exposure variables and outcomes in the study population are presented in Table 1. Sick leave prevalence is higher in extremely female-dominated occupations and branches, and among men in extremely male-dominated occupations and branches. For combinations of gender segregation in occupations and branches, sick leave prevalence is higher among both women and men in female occupations in female branches and among men in male occupations in male branches. The independent role for sick leave of working in diverse occupations and branches were assessed for 11 and 10 overarching categories presented in Table 2.

Outcome—compensated sick leave

Cases of sick leave compensated by Swedish sickness insurance were retrieved from the MiDAS database (Micro Data for Analysis of Social Insurance) with data originating from registers held by the SSIA. All spells exceeding 14 days with onset during 2015 and 2016 were included in the study. Medically certified sick leave exceeding 2 weeks could be considered less voluntary and therefore closely connected to illness and disease (Kivimäki et al. 2003). Recurrent spells were excluded so each individual only contributed with one spell in the analysis. The total number of spells was 685, 184 with 430, 317 for women.

Confounders

Several variables originating from the registers held by the SSIA, recorded at baseline in December 2014, were used as covariates for prospective sick leave. All covariates used were categorical and the categories for each covariate are presented in Table 2. The covariates were considered relevant according to previous studies (Allebeck and Mastekaasa 2004; Swedish Social Insurance Agency 2018). The covariates were sickness insurance history, age, civil status, children in the family and their age, country of birth, income from work, waiting days in sickness insurance and finally type of municipality of residence (according to the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, SKL 2017, elaborated with population and commuter data from 2014). Additional covariates such as education, employment sector, occupation and branch originate from registers held by Statistics Sweden and recorded at baseline in December 2014. In the analyses of gender segregation, adjustments were made for 113 occupations (three-digit level constituting minor occupational groups) and 89 branches (two-digit level constituting branch divisions). Hence, adjustments for occupation and branch were made at a more aggregated level than gender segregation.

Statistical analyses

Logistic regression was used to analyse the odds of prospective sick leave and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Since sick leave was fairly common, the odds ratios (OR) were recalculated to relative risks (RR) according to the formula RR = OR/(1 + OR). Missing values for covariates constitute distinct categories in the analysis, but their results are not presented since they lack meaningful interpretation. Furthermore, all analyses have been stratified by sex. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows (release 23).

Results

In Table 3, crude and adjusted relative risks for sick leave are presented for women and men. The crude risks are U-shaped with higher risks in female- and male-dominated occupations for both women and men, with the highest risks in extremely gender-segregated occupations. Crude risks for branches also show a U-shaped pattern with the exception of women working in extremely male-dominated branches. However, after adjustment for occupation, branch and other covariates, the U-shaped patterns are eroded, see Fig. 1 and 2. Among both women and men, higher sick leave risks are still evident in female-dominated occupations and branches, especially for men. Among men, there is also a slightly higher risk in extremely male-dominated branches. For particular branches, the sick leave risks are higher among women working within transportation, education and social services. Among men, the same holds for those working within construction and social services. For particular occupations, the gaps in sick leave between groups are wide-ranging among both women and men, with higher risks for blue collar occupations, particularly for crafts and related trades workers, plant and machine operators and assemblers, and for elementary occupations.

In Table 4, results for combinations of occupational and branch gender segregation are presented for women and men. The familiar U-shaped pattern is obvious in the crude analyses with low sick leave risks among women and men working in integrated occupations in integrated branches. With adjustments, sick leave is higher among women within female branches in female or integrated occupations, and among women in female occupations in integrated branches. Among men, sick leave is higher in female occupations regardless of branch gender segregation and in female branches regardless of the occupational gender segregation.

Discussion

As expected, the results from the study show that without adjusting for confounders there is a clear U-shaped association for occupational gender segregation as found in several other studies (Alexanderson et al. 1994; Bryngelsson et al. 2011; Laaksonen et al. 2012; Leijon et al. 2004; Mastekaasa 2005; Melsom and Mastekaasa 2018). Without adjustment, a U-shaped pattern also appears for branch gender segregation, with women in extremely male-dominated branches as the exception. However, with adjustment for occupation, branch and other confounders, the U-shaped patterns eroded. Higher sick leave risks were evident mainly in female-dominated occupations and branches for both sexes. The highest risks were found among men in extremely female-dominated occupations with a relative risk of 1.13 and among men in extremely female-dominated branches with a relative risk of 1.12, compared to men in integrated occupations and branches.

Combining gender segregation for occupations and branches further emphasized the higher sick leave risks found in female-dominated occupations and branches, with some exceptions. Women in male-dominated branches did not have higher sick leave risks regardless of the gender structure in their occupation. A possible explanation could be positive health selection among women into male branches for those holding a sex integrated or male occupation (Grönlund and Magnusson 2018; Hensing and Alexanderson 2004; Kröger 2016; Melsom and Mastekaasa 2019; Milner et al. 2018). For women working in female occupations in male branches it may also be protective to adhere to prevailing gender norms about occupational choices (Grönlund and Magnusson 2018; Kröger 2017; Jonsson et al. 2013), which could be considered as positive tokenism at the workplace (Kanter 1977). In addition, women working in male-dominated branches may also adhere to cultures of low sick leave (Laaksonen et al. 2012; Löset et al. 2018; Nicholson and Johns 1985; Virtanen et al. 2000). Positive health selection may also play a role for women working in male-dominated occupations, even though some of this have been accounted for in the study through adjustment for previous sick leave.

In contrast, female-dominated occupations and branches appear problematic for worker health. Among men, sick leave is higher in female occupations regardless of branch gender segregation and also in female branches regardless of occupation gender segregation. Negative health selection for men into female-dominated occupations may play a role. However, as male-dominated economic activities are being higher valued and prestigious in society, males breaking traditional gender norms by working in gender atypical occupations or branches may face negative tokenism both in and outside work (Kanter 1977; Kröger 2017; Jonsson et al. 2013). Even though men may be welcomed in female-dominated occupations as bearers of potential higher status to the occupation (Kröger 2017; Jonsson et al. 2013), a potential positive tokenism at work could possibly be overridden by negative tokenism in society as a whole. In addition, men working in female-dominated occupations and branches may also adhere to more lenient attitudes towards sick leave (Laaksonen et al. 2012; Löset et al. 2018; Nicholson and Johns 1985; Virtanen et al. 2000).

Besides the potential role of a gender minority position at the workplace, health selection into occupations and branches, and sick leave cultures and attitudes at workplaces, there are substantial differences in working conditions between occupations and branches in general and between female- and male-dominated occupations and branches in particular (Bryngelson et al. 2011; Jonsson et al. 2013; Lidwall et al. 2018; The Swedish Work Environment Authority 2016). Even though the current study adjust for occupation and branch at a more aggregated level as proxies for working conditions in the analyses, it does not explicitly account for adverse working conditions. Hence, it cannot be ruled out that the used measures of gender segregation capture the poorer working conditions in the gender-segregated parts of the labour market. Some evident examples in the Swedish context, are poorer psychosocial working conditions within the female-dominated tax financed human service sector and poorer physical working conditions within the male-dominated private enterprise construction sector (The Swedish Work Environment Authority 2016). The effects on sick leave of these working conditions for women and men could be further reinforced or mitigated by health selection (Nordström et al. 2016; Melsom and Mastekaasa 2018) and gendered cultures of absenteeism or presenteeism (Kröger 2017; Laaksonen et al. 2012).

However, despite the role of gender segregation for subsequent medically certified sick leave, it appears modest in comparison with differences in risks between particular occupations and branches (Lidwall et al. 2018; Swedish social insurance agency 2018; Montano 2020). While, for illustrative purposes, solely using a crude number of 10 and 11 categories in the analyses, the span in relative risks between branches and occupations was 18 and 38 percentage points among women, and 20 and 44 among men. Not surprisingly, studies using more detailed occupations and branches present substantially larger differences (Lidwall et al. 2018; Swedish social insurance agency 2018). Hence, gender segregation appears subordinate in comparison with particular occupational hazards faced in different occupations and branches and their associated socioeconomic factors. Many studies aiming at finding general patterns for entire labour markets often overlook the complexity reflected by the number of occupations and branches represented in post-industrial economies (Statistics Sweden 2001, 2007; Lidwall et al. 2018; Swedish social insurance agency 2018). Furthermore, there is a need for theoretical development regarding the role of gender segregation at the workplace, and a more solid base underpinning the mechanisms behind potential adverse health consequences. A possible interpretation of the results is that gender segregation at workplaces is not particularly problematic per se, but rather serves as an indicator of gender inequality and social injustice at the labour market (Messing et al. 1998). Gender inequality and injustice could probably be better researched and addressed by more direct measures such as bullying, harassment, discrimination, unequal pay and organisational justice. From a policy perspective, the most important factors for women and men at the Swedish labour market struggling in their work is prevailing physical health hazards, job strain, effort reward imbalance and work–life imbalance (Bryngelson et al. 2011; Jonsson et al. 2013; Lidwall et al. 2018; Lidwall 2016; The Swedish Work Environment Authority 2016; Montano 2020).

Methodological considerations

This study has several advantages including the prospective design and accounting for baseline health as reflected in sickness insurance and a large heterogeneous population of an entire country. All Swedish employees in ages 16–69 years were included in the study. Hence, the external validity for the Swedish society is high as should also be the case for comparable countries. In addition, the register data used in the analysis are in general very reliable. A further strength is that a number of relevant confounders were considered in the regression analysis. For instance, the general adjustment for occupation and branch at a more aggregated level reduce the potential bias due to differences in exposures at work as well as other socioeconomic factors. Still, a more detailed adjustment for other working conditions would probably attenuate the role of gender segregation even further. Nevertheless, the study has limitations. As in all observational studies, the possible impact of residual confounding from other unmeasured or poorly measured covariates cannot be excluded. However, there is no single factor that has not been included in the analyses that is a likely candidate to explain the main findings by confounding. Still, the observational nature of the study inherently opens up for the possibility that other potential predictors influence the outcomes.

Conclusion

Gender segregation in occupations and branches play a role for sick leave among women and men in Sweden, especially within extremely female-dominated occupations and branches. However, gender segregation appears to be subordinate to particular occupational hazards faced in different occupations and branches.

References

Allebeck P, Mastekaasa A (2004) Chapter 5. Risk factors for sick leave—general studies. Scand J Public Health 32:49–108

Alexanderson K, Leijon M, Akerlind I, Rydh H, Bjurulf P (1994) Epidemiology of sickness absence in a Swedish county in 1985, 1986 and 1987 A three year longitudinal study with focus on gender, age and occupation. Scand J Soc Med 22(1):27–34

Berglund L, Johansson M, Nygren M, Samuelson B, Stenberg M, Johansson J (2019) Occupational accidents in Swedish construction trades. Int J Occup Saf Ergon JOSE 1–10

Bryngelson A, Bacchus Hertzman J, Fritzell J (2011) The relationship between gender segregation in the workplace and long-term sickness absence in Sweden. Scand J Public Health 39(6):618–626

Elwer S, Johansson K, Hammarström A (2014) Workplace gender composition and psychological distress: the importance of the psychosocial work environment. BMC Public Health 14:241

Evans O, Steptoe A (2002) The contribution of gender-role orientation, work factors and home stressors to psychological well-being and sickness absence in male- and female-dominated occupational groups. Soc Sci Med (1982) 54(4):481–492

Gaspar FW, Zaidel CS, Dewa CS (2018) Rates and predictors of recurrent work disability due to common mental health disorders in the United States. PLoS ONE 13(10):e0205170

Gonäs L, Wikman A, Vaez M, Alexanderson K, Gustafsson K (2019) Gender segregation of occupations and sustainable employment: a prospective population-based cohort study. Scand J Public Health 47(3):348–356

Grönlund A, Magnusson C (2018) Do atypical individuals make atypical choices? Examining how gender patterns in personality relate to occupational choice and wages among five professions in Sweden. Gend Issues 35(2):153–178

Hensing G, Alexanderson K (2004) The association between sex segregation, working conditions, and sickness absence among employed women. Occup Environ Med 61(2):e7

Irastorza X, Milczarek M, Cockburn W, European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) (2016) Second European survey of enterprises on new and emerging risks (ESENER-2). Overview report: managing safety and health at work. European agency for safety and health at work, Luxembourg

Jonsson R, Lidwall U, Holmgren K (2013) Does unbalanced gender composition in the workplace influence the association between psychosocial working conditions and sickness absence? Work 46(1):59–66

Kanter RM (1977) Men and women of the corporation. Basic Books, New York

Kivimäki M, Head J, Ferrie J, Shipley M, Vahtera J, Marmot M (2003) Sickness absence as a global measure of health: evidence from mortality in the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ 327(7411):364–369

Kristman VL, Shaw WS, Boot CR, Delclos GL, Sullivan MJ, Ehrhart MG (2016) Researching complex and multi-level workplace factors affecting disability and prolonged sickness absence. J Occup Rehabil 26(4):399–416

Kröger H (2016) The contribution of health selection to occupational status inequality in Germany—differences by gender and between the public and private sectors. Public health 133:67–74

Kröger H (2017) The stratifying role of job level for sickness absence and the moderating role of gender and occupational gender composition. Soc Sci Med (1982) 186:1–9

Laaksonen M, Martikainen P, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E (2012) The effect of occupational and workplace gender composition on sickness absence. J Occup Environ Med 54(2):224–230

Leijon M, Hensing G, Alexanderson K (2004) Sickness absence due to musculoskeletal diagnoses: association with occupational gender segregation. Scand J Public Health 32(2):94–101

Lidwall U (2016) Effort–reward imbalance, overcommitment and their associations with all-cause and mental disorder long-term sick leave—a case–control study of the Swedish working population. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 29(6):973–989

Lidwall U, Bill S, Palmer E, Olsson Bohlin C (2018) Mental disorder sick leave in Sweden: a population study. Work (Reading, Mass) 59(2):259–272

Loset GK, Dale-Olsen H, Hellevik T, Mastekaasa A, von Soest T, Ostbakken KM (2018) Gender equality in sickness absence tolerance: attitudes and norms of sickness absence are not different for men and women. PLoS ONE 13(8):e0200788

Marshall NL, Barnett RC, Sayer A (1997) The changing workforce, job stress, and psychological distress. J Occup Health Psychol 2(2):99–107

Mastekaasa A (2005) Sickness absence in female- and male-dominated occupations and workplaces. Soc Sci Med (1982) 60(10):2261–2272

Melsom AM, Mastekaasa A (2018) Gender, occupational gender segregation and sickness absence: longitudinal evidence. Acta Sociol 61(3):227–245

Messing K, Tissot F, Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Kaminski M, Bourgine M (1998) Sex as a variable can be a surrogate for some working conditions: factors associated with sickness absence. J Occup Environ Med 40(3):250–260

Milner A, King T, LaMontagne AD, Bentley R, Kavanagh A (2018) Men’s work, women’s work, and mental health: a longitudinal investigation of the relationship between the gender composition of occupations and mental health. Soc Sci Med (1982) 204:16–22

Montano D (2020) A psychosocial theory of sick leave put to the test in the European Working Conditions Survey 2010–2015. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 93(2):229–242

Nicholson N, Johns G (1985) The absence culture and the psychological contract—who’s in control of absence? Acad Manag Rev 10(3):397–407

Nordström K, Hemmingsson T, Ekberg K, Johansson G (2016) Sickness absence in workplaces: does it reflect a healthy hire effect? Int J Occup Med Environ Health 29(2):315–330

Nyberg A, Magnusson Hanson LL, Leineweber C, Hammarstrom A, Theorell T (2018) Occupational gender composition and mild to severe depression in a Swedish cohort: the impact of psychosocial work factors. Scand J Public Health 46(3):425–432

Swedish Social Insurance Agency (2018) Sjukfrånvaron på svensk arbetsmarknad. In Swedish [Sick leave on the Swedish labour market]. Socialförsäkringsrapport 2018:2. Försäkringskassan: Stockholm

Statistics Sweden (2001) SSYK96 Swedish standard classification of occupations 1996. MiS 1998:3. SCB: Örebro

Statistics Sweden (2007) SNI 2007 Swedish standard industrial classification 2007. MiS 2007:2. SCB: Örebro

The Swedish work environment authority (2016) The work environment 2015. Arbetsmiljöstatistik Rapport 2016:2. Arbetsmiljöverket: Stockholm

Virtanen P, Nakari R, Ahonen H, Vahtera J, Pentti J (2000) Locality and habitus: the origins of sickness absence practices. Soc Sci Med (1982) 50:27–39

Virtanen P, Vahtera J, Nygard CH (2010) Locality differences of sickness absence in the context of health and social conditions of the inhabitants. Scand J Public Health 38(3):309–316

Wieclaw J, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB, Bonde JP (2006) Risk of affective and stress related disorders among employees in human service professions. Occup Environ Med 63(5):314–319

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Since only register data were used no informed consent was required from participants. The Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SSIA) is the Government authority in Sweden responsible for social insurance statistics and the author is a senior research officer at the Statistics Department at the SSIA. The current register data are stored and processed under strict secrecy in accordance with Swedish law on official statistics (2001:99) and the data can only be used for production of social insurance statistics or research within the SSIA.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lidwall, U. Gender composition in occupations and branches and medically certified sick leave: a prospective population study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 94, 1659–1670 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01672-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01672-4