Abstract

Study aim

We hypothesise that due to a lower quality of working life and higher job insecurity, the health and work-related attitudes of temporary workers may be less positive compared to permanent workers. Therefore, we aimed to (1) examine differences between contract groups (i.e. permanent contract, temporary contract with prospect of permanent work, fixed-term contract, temporary agency contract and on-call contract) in the quality of working life, job insecurity, health and work-related attitudes and (2) investigate whether these latter contract group differences in health and work-related attitudes can be explained by differences in the quality of working life and/or job insecurity.

Methods

Data were collected from the Netherlands Working Conditions Survey 2008 (N = 21,639), and Hypotheses were tested using analysis of variance and cross-table analysis.

Results

Temporary work was associated with fewer task demands and lower autonomy and was more often passive or high-strain work, while permanent work was more often active work. Except for on-call work, temporary work was more insecure and associated with worse health and work-related attitude scores than permanent work. Finally, the quality of working life and job insecurity partly accounted for most contract differences in work-related attitudes but not in health.

Conclusions

Especially agency workers have a lower health status and worse work-related attitudes. Job redesign measures regarding their quality of working life and job insecurity are recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the European Union (EU 27), the percentage of employees with limited contract duration has increased from 11.8% in 1999 to 14% in 2010, currently involving around 24 million workers (Eurostat 2011a, b). The share of agency workers sharply increased from 1.1 to 1.7% and is now worldwide estimated at 9.5 million workers (in 2008 in FTE: Ciett 2010). This increase in non-standard employment may reflect a segmented labour market, with organisational insiders (those with standard working arrangements such as full-time permanent workers) and organisational outsiders (those holding non-standard working arrangements, such as temporary agency workers) (Kalleberg 2003). In line with this, many organisations today have a core–periphery structure, with permanent workers in a core surrounded by a periphery of layers of flexible, less secure temporary workers (Auer and Cazes 2000; Ferrie et al. 2008). Therefore, much research has been carried out to examine the potential risks of temporary employment, and its impact on workers’ health, well-being and work-related attitudes (De Cuyper et al. 2008).

Temporary employment, labour market segmentation and the quality of working life

Three related theoretical perspectives suggest that temporary work is (1) low-quality work and (2) highly insecure work. First, the insider–outsider idea (standard vs. non-standard employment: Kalleberg 2003) stems from the aforementioned segmentation theories, which divide the labour market into core and peripheral workers (Atkinson 1984; Becker 1993; Hudson 2007). Core workers possess job-specific skills and are therefore hard to replace and thus important to their company. In order to tie these workers to their organisation, employers must offer them high-quality employment, including learning opportunities, job security and a proper salary (Hudson 2007). In contrast, employers do not need to tie the less important and more easily replaceable peripheral workers to their organisation. Consequently, these workers receive less attractive working conditions and lower earnings than primary segment workers.

Secondly and related to segmentation theories, temporary employment is expected to include more adverse job characteristics than permanent work (De Cuyper et al. 2008; De Witte and Näswall 2003). For example, temporary work has been associated with worse ergonomic conditions, lower earnings, less autonomy, less supervisory tasks, a higher dynamic work load, more repetitive tasks, monotonous work, less training opportunities and exposure to discrimination (Brown and Sessions 2003; De Cuyper et al. 2008; Goudswaard and Andries 2002; Kompier et al. 2009; Layte et al. 2008; Letourneux 1998; Parent-Thirion et al. 2007); but also often with (indicators of) lower task demands (De Cuyper and De Witte 2006; Goudswaard and Andries 2002; Kompier et al. 2009; Letourneux 1998; Parker et al. 2002). Based on theories on well-designed ‘healthy’ work (Kompier 2003), it can be expected that such characteristics (e.g. combinations of high [but also low] demands and low control, low feedback, low support and high job insecurity) adversely impact workers’ health, well-being and work-related attitudes.

Temporary employment and job insecurity

A third perspective focuses on the impact of job insecurity on temporary workers’ health and well-being. Job insecurity, which increases with the temporality of the job (De Cuyper et al. 2008), implies uncertainty and thus unpredictability and uncontrollability. This can be linked to central elements of job stress theories (e.g. environmental clarity and lack of control) (De Witte 1999). Moreover, according to Jahoda’s (1982) latent deprivation model, employment is central to many people’s lives as it fulfils important needs as income, social contacts and opportunities for self-improvement. Threat and worry about job loss thus include potential loss of important resources and may therefore have many negative consequences for the worker involved (De Witte 1999). For example, job insecurity has been associated with lower work satisfaction, less organisational commitment, less organisational trust, deteriorated physical and mental health, lower self-esteem, reduced performance and increased turnover intention (Cheng and Chan 2008; De Witte 1999; Ferrie et al. 2002; Hellgren and Sverke 2003; Kinnunen et al. 2003; Lau and Knardahl 2008; Sverke et al. 2002. Virtanen et al. 2011).

Impact of temporary employment on health, well-being and work-related attitudes

The combination of (1) a lower quality of working life and (2) higher job insecurity may make temporary work less healthy and satisfying. Indeed, non-standard employment has been associated with poorer health, lower well-being and higher mortality (Aronsson et al. 2002; Benach et al. 2004; De Cuyper et al. 2008; Kawachi 2008; Kivimäki et al. 2003; Kompier et al. 2009; M. Virtanen et al. 2005; P. Virtanen et al. 2005; Waenerlund et al. 2011). However, such contract differences have been often found to be inconsistent and inconclusive (for an overview see De Cuyper et al. 2008). For example, De Cuyper and De Witte (2006) found no evidence for mediation by workload or autonomy between the type of employment contract (permanent vs. fixed-term) and work-related attitudes. To date, many reasons for such inconsistent findings have been offered (De Cuyper et al. 2008). These can generally be divided into (1) conceptual issues and (2) methodological issues (Kompier et al. 2009). The main conceptual issue is the heterogeneity of the temporary workforce. Temporary contracts may differ in various respects, including perceived job insecurity, the quality of working life and their demographical composition in terms of gender, age, ethnicity and educational level (Connelly and Gallagher 2004; De Cuyper et al. 2008). Methodologically, most research is cross-sectional and usually refers to specific groups of workers, for example within a particular sector and country, meaning that causal relationships cannot be drawn and findings may not generalise to other groups of workers.

Research goal and hypotheses

Against this background, the goal of the current study was twofold. First, in a large and representative sample of the Dutch working population, we aimed to examine employment contract differences [i.e. between permanent, temporary with prospects on permanent employment (semi-permanent), fixed-term without prospects (temporal-no prospect), agency work and on-call work] in (1) the quality of working life (i.e. task demands and autonomy), (2) job insecurity, (3) health (i.e. general health, musculoskeletal symptoms and emotional exhaustion) and (4) work-related attitudes (work satisfaction, turnover intention and employability). We expect agency and on-call workers to have the lowest autonomy and fewest task demands, while the opposite is expected for permanent workers (Hypothesis 1a). In line with this, temporary work (especially agency and on-call work) may be more often passive work (i.e., low control and low demands), and permanent work more often active work (high control and high demands) (Hypothesis 1b). Based on the peripheral nature of agency and on-call work, these workers are expected to report the highest job insecurity and permanent workers the lowest (Hypothesis 2). With regard to contract differences in health, we expect similar results. Due to the expected lower quality of working life and higher job insecurity among agency and on-call workers, this group should have the lowest health status and permanent workers the highest (Hypothesis 3). Similarly, agency and on-call workers are expected to have the least favourable work-related attitudes, while the opposite should hold true for permanent workers (Hypothesis 4).

Secondly, we aimed to determine the role of the quality of working life and job insecurity in the relationship between employment contracts and (5) health and (6) work-related attitudes. We expect the contract differences in health to be partly explained by the quality of working life (Hypothesis 5a) and the degree of job insecurity (Hypothesis 5b). Moreover, we expect these contract differences to be best explained by the combination of the quality of working life and job insecurity (Hypothesis 5c). Similarly, we expect the contract differences in work-related attitudes to be also partly explained by the quality of working life (Hypothesis 6a) and job insecurity (Hypothesis 6b). Again, we expect that these differences in work-related attitudes will be best explained by the combination of quality of working life and job insecurity (Hypothesis 6c).

Methods

Sample

Data for the current study were obtained from the Netherlands Working Conditions Survey 2008 (NWCS: Koppes et al. 2009), which focused on the Dutch working population, excluding self-employed. This survey consists of a written questionnaire, which was sent to the respondents’ homes. Participants were asked to fill in and return the questionnaire or to complete an online version of the questionnaire. Responses were obtained from 22,025 participants (30.8% response rate). The data were weighted to increase its representativeness for the Dutch working population, for example with regard to gender, age, ethnicity and occupation (Koppes et al. 2009). Because we restricted our analyses to workers holding a permanent or temporary contract, our final sample comprised 21,639 participants. Their mean age was 40.2 years (SD = 12.0), and 53.7% was male.

Measures

Employment contract

The question ‘what is the nature of your employment?’ distinguished among five contract types: 1 = employee with permanent employment (for indefinite time), 2 = employee with temporary employment with prospect on permanent employment, 3 = employee with temporary employment for a fixed term, 4 = temporary agency work and 5 = on-call work. It should be noted that, although all temporary workers are protected by the so-called flex-law in the Netherlands, this flex-law does not include specific arrangements for on-call workers. However, the latter can be characterised as having non-standard work schedules and only performing work when called upon by their employer (Verhulp et al. 2002). In general, these workers enjoy similar labour protection as other temporary workers.

Quality of working life

To assess the quality of working life, we measured task demands, autonomy and computed the combination of both characteristics (i.e. Karasek’s quadrants: active, passive, high-strain and low-strain work; Karasek 1985). The 4-item Task demands scale (e.g. ‘do you have to perform a lot of work?’ and ‘do you need to work extra hard?’; 1 = ‘never’, 2 = ‘sometimes’, 3 = ‘often’, 4 = ‘always’) and the 3-item Autonomy scale (e.g. ‘can you regulate your work pace?’ and ‘can you decide yourself how to perform your work?’; 1 = ‘yes, regularly’, 2 = ‘yes, sometimes’, 3 = ‘no’ [reverse coded]) were derived from the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ: Karasek 1985; Karasek et al. 1998).

In order to compute four combinations of high–low scores on both factors and, thus, to distinguish between the four quadrants proposed by Karasek (1979), we first divided the participants in a group with low demands (i.e. those with an average score of M ≤ 2 on the job demands scale, which corresponds with the answer category ‘sometimes’ of the items of this scale), and a group with high demands (i.e. those with an average score of >2, meaning that job demands are experienced more frequently than ‘sometimes’). Similarly, based on the autonomy scale, we divided the participants into a low and a high control group (low control = M ≤ 2; high control = M > 2). Finally, we combined these groups into the four Karasek quadrants: passive work (low demands and low control), active work (high demands and high control), low-strain work (low demands and high control) and high-strain work (high demands and low control).

Job insecurity

Job insecurity was measured with a two question-scale derived from Goudswaard et al. (1998): (1) ‘are you at risk of losing your job?’ and (2) ‘are you worried about retaining your job?’ (1 = ‘yes’; 2 = ‘no’ [reverse coded]).

Health

Health was measured using three scales. General health was assessed with the question ‘generally taken, how would you define your health?’ (1 = ‘excellent’, 2 = ‘very good’, 3 = ‘good’, 4 = ‘moderate’, 5 = ‘bad’ [reverse coded]), derived from Statistics Netherlands (CBS 2003). Musculoskeletal symptoms were measured with four items (‘in the past 12 months, did you have trouble (pain, discomfort) from your:’ (1) ‘neck’, (2) ‘shoulders’, (3) ‘arms/elbows’ and (4) ‘wrists/hands’) based on the work of Blatter et al. (2000), and two additional items referring to (5) back complaints and (6) hip, legs, knees and feet complaints (1 = ‘no, never; 2 = ‘sometimes, short lived’; 3 = ‘sometimes, long lasting’; 4 = ‘multiple times, short lived’; 5 = ‘multiple times, long lasting’). Emotional exhaustion was measured with five items, adapted from the corresponding scale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS: Schaufeli et al. 1996). A typical item is: ‘I feel burned out from my work’ (1 = ‘never’, 7 = ‘every day’).

Work-related attitudes

Three work-related attitudes were measured, namely work satisfaction, turnover intention and employability. Work satisfaction was measured with two questions, ‘to what extent are you, all in all, satisfied with your work?’ and ‘to what extent are you, all in all, satisfied with your working conditions?’, respectively (1 = ‘very dissatisfied’, 5 = ‘very satisfied’). Turnover intention was assessed with two questions derived from Goudswaard et al. (1998): (1) ‘in the past year, did you consider to search for another job than the job at your current employer?’ and (2) ‘in the past year, have you actually undertaken something to find another job?’ (1 = ‘yes’; 2 = ‘no’ [reverse coded]). Employability was measured with the question ‘if you compare yourself with your colleagues, are you more broadly employable in your company than your colleagues?’ (1 = ‘yes, more broadly employable’; 2 = ‘no, comparable to others’; 3 = ‘no, less broadly employable’ [reverse coded], cf. Verboon et al. 1999).

Finally, age (in years) was used as a continuous control variable in the analyses including workers’ health status because temporary workers are on average much younger and therefore healthier than permanent workers, cf. M. Virtanen et al. 2005. If applicants voiced no opinion on a question, this was coded as a missing answer. For all scales, we computed average scores per item. The theoretical range of all measures, descriptive statistics, correlations and Cronbach’s alphas are summarised in Table 1. It should be noted that instead of Cronbach’s alpha, we reported the more appropriate Kuder-Richardson Rho (KR-20) for our dichotomous measures (Zeller and Carmines 1980).

Statistical procedure

Hypothesis 1 (contract differences in the quality of working life) was tested using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and cross-table analysis. First, we conducted a MANOVA with the type of employment contract as independent variable and the quality of working life indicators (task demands and autonomy) as dependent variables, followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test. Cohen’s D values were computed for effect sizes and were interpreted in line with Cohen (1988), as small (d < 0.5), moderate (d = 0.5–0.8) or large (d > 0.8). Further, we conducted cross-table analysis to examine whether the number of workers holding an active, passive, high-strain or low-strain job varied as a function of employment contract.

To test Hypothesis 2 (contract differences in job insecurity), we conducted an ANOVA with a Bonferroni post-hoc analysis and computed corresponding Cohen’s D values. Type of employment contract was the independent variable, and job insecurity was the dependent variable.

In order to test Hypothesis 3 and 4, MAN(C)OVAs were used with the type of employment contract as independent variable. To test Hypothesis 3 (contract differences in health), we entered general health, musculoskeletal symptoms and emotional exhaustion as dependent variables and repeated this analysis with age as a covariate. Next, we entered work satisfaction, turnover intention and employability as dependent variables to test Hypothesis 4 (contract differences in work-related attitudes). For both analyses, we conducted Bonferroni post-hoc analyses and computed corresponding Cohen’s D values.

Hypothesis 5 [contract differences in health are explained by the quality of working life (5a), job insecurity (5b) and their combination (5c)] was tested by repeating the MANCOVA conducted for testing Hypothesis 3 with the quality of working life indicators (i.e. task demands and autonomy) as additional covariates. To test Hypothesis 5b, we repeated this analysis with job insecurity as a covariate instead of the quality of working life indicators. Finally, Hypothesis 5c was tested using both the quality of working life indicators and job insecurity as covariates.

Similarly, Hypothesis 6 [contract differences in work-related attitudes explained by the quality of working life (6a), job insecurity (6b) and their combination (6c)] was first tested by repeating the MANOVA conducted for testing Hypothesis 4, but with the quality of working life indicators (i.e. task demands and autonomy) as covariates. In the same way, we tested Hypothesis 6b, by using job insecurity as a covariate. Finally, we tested Hypothesis 6c by using both the quality of working life indicators and job insecurity as covariates.

Results

Contract types and quality of working life

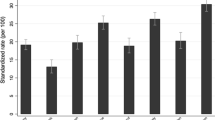

Hypothesis 1a stated that especially agency and on-call workers would experience less autonomy and fewer task demands than permanent workers. The results presented in Table 2 support this hypothesis. The largest difference in autonomy (i.e. between permanent and agency workers) represents a moderate effect, while the largest difference in task demands (i.e. between permanent and on-call workers) represents a small effect. Moreover, agency and on-call workers did not differ significantly in their scores on autonomy and task demands. Furthermore, the results of the cross-table analysis (Table 2) support Hypothesis 1b. As expected, permanent work was more often active work (i.e. high demands and high control), while temporary work was more often passive work (i.e. low demands and low control). However, temporary work was also more often high-strain work (i.e. high demands and low control). Thus, both Hypotheses 1a and 1b were supported.

Contract types and job insecurity

Hypothesis 2 held that agency and on-call workers would experience the highest and permanent workers the lowest job insecurity. The results in Table 2 support this expectation for agency work, but not for on-call work. Moreover, the largest difference in job insecurity was found for permanent versus agency work (large effect). In contrast, job insecurity among on-call workers was roughly the same as among (semi-)permanent workers. Thus, Hypothesis 2 receives support for agency work, but not for on-call work.

Contract types, health and work-related attitudes

Hypothesis 3 and 4 stated that agency and on-call workers would have the lowest health status and the worst work-related attitudes scores, respectively, while the opposite was expected for permanent workers. Regarding contract differences in health (Hypothesis 3), the findings in Table 3 support this expectation for agency work, but not for on-call work. Agency workers had the worst scores on general health, musculoskeletal symptoms and emotional exhaustion, while the opposite was true for on-call workers. However, all differences between contract groups were small, and the F-value for general health was strongly reduced after controlling for age (Hypothesis 3 partially supported). As regards the contract differences in work-related attitudes (Hypothesis 4), Table 4 shows that permanent workers indeed had the best scores, while agency workers reported the lowest work satisfaction, the highest turnover intention and (together with the ‘temporal-no prospect’ workers) the lowest employability. Again, on-call workers did not report the worst scores, as they were about as satisfied with their work as permanent workers. However, most of these contract differences were small, and Hypothesis 4 thus received partial support.

Contract differences in health explained

Hypothesis 5 stated that the contract differences in health would be partly explained by the quality of working life (5a), job insecurity (5b) and the combination of both (5c). First, note that in the analyses including job insecurity as an additional covariate to age, the effect of age on contract differences in emotional exhaustion became non-significant. Secondly, the quality of working life hardly reduced the contract differences in health, as the F-values controlled for the quality of working life and age (Table 3) were similar to the F-values only controlled for age (Hypothesis 5a not supported). Furthermore, the expected reduction due to job insecurity was only supported for musculoskeletal symptoms, while the F-values for general health and emotional exhaustion increased (Hypothesis 5b partially supported). Finally, the contract differences in health could not for the largest part be explained when controlling for both the quality of working life and job insecurity (Hypothesis 5c not supported).

Contract differences in work-related attitudes explained

Hypothesis 6 consists of three subhypotheses. First, we expected the quality of working life to partly explain contract differences in work-related attitudes (6a). Indeed, as shown in Table 4, the quality of working life reduced most (i.e. 2 out of 3) F-values for these contract differences (namely those for work satisfaction and employability), but the F-value for turnover intention increased (Hypothesis 6a partially supported). Secondly, all F-values for the contract differences in work-related attitudes, especially those for work satisfaction and turnover intention, decreased when controlling for job insecurity (Hypothesis 6b supported). Finally, most (i.e. 2 out of 3) F-values in Table 4 (namely those for work satisfaction and employability) were reduced most when controlling for both the quality of working life and job insecurity (Hypothesis 6c thus partially supported).

Discussion

Temporary work is on the increase in the European Union, and there is some concern as regards the quality of working life, job insecurity, health and well-being of these temporal employees. In a large and representative sample of the Dutch working population, we first investigated contract differences in the quality of working life, job insecurity, health and work-related attitudes. Secondly, we investigated the role of the quality of working life and job insecurity in the relation between different employment contracts and health and work-related attitudes. Table 5 summarises the support for each of our hypotheses.

Theoretical implications

Four theoretical implications can be derived from the current study. First, we found support for a multi-layered core–periphery structure (Ferrie et al. 2008), meaning that from the core of permanent workers to the periphery of agency workers, work autonomy and task demands decreased, whereas job insecurity increased. In line with Goudswaard and Andries (2002), we also found the prevalence of both passive and high-strain jobs to increase with the temporality of the contract, which illustrates the heterogeneity within the temporary workforce (De Cuyper et al. 2008).

Secondly, not all ‘peripheral’ contracts were associated with negative outcomes, which underline the need to distinguish among different forms of temporary employment (De Cuyper et al. 2008; Kompier et al. 2009). Especially, agency work was of low quality (i.e. relatively low autonomy, high job insecurity and an unfavourable health status and unfavourable work-related attitudes). However, on-call work seemed to be a distinct form of temporary work, as a large share of these workers had high-strain work, but overall they had favourable scores on job insecurity, health and work satisfaction, quite comparable to those of permanent workers. Therefore, we conducted additional post-hoc analyses to examine both categories of temporary workers in more detail, revealing that in our sample the prevalence of agency work was lower than that of on-call work [1.8% (N = 392) vs. 2.2% (N = 467)]. Furthermore, agency workers were less often females (45.0% vs. 59.4%), young workers (13.5% vs. 44.5% ≤ 20 years) and low educated (29.4% vs. 39.4%), and they worked more days [4.2 (SD = 1.4) vs. 2.7 (SD = 1.5)] and more hours [28.3 (SD = 14.7) vs. 7.6 (SD = 9.6)] a week than on-call workers. Moreover, they were relatively often employed in the business services (36.0%), industry (13.3%) and transport (10.6%) sectors, whereas on-call workers were most often employed in the health care (28.1%), catering (19.1%) and trading (20.2%) sectors. This suggests that a large share of on-call workers may be (high school) students holding part-time jobs (because they are young, low educated and only employed for a few hours a week), for whom paid work is not especially salient. This may explain their low job insecurity, which in combination with little exposure to low-quality work (i.e. only few hours a week) may explain their favourable health status and high job satisfaction.

The third and fourth implication can be derived from the answer to our title question: “Can labour contract differences in health and work-related attitudes be explained by quality of working life and job insecurity?”. Both aspects could hardly explain contract differences in health, whereas they could not fully explain contract differences in work-related attitudes. First, regarding health, we should note that many contract differences (i.e. in general health and musculoskeletal symptoms) were already small, especially after controlling for age. Moreover, work-related variables as the quality of working life and job insecurity may only have a small impact on a multidimensional outcome as general health (Virtanen et al. 2011). Nevertheless, both aspects failed to explain contract differences in emotional exhaustion, which is a work-related health outcome. It does not seem plausible that this depends upon poor measurement of the quality of working life (i.e. autonomy and task demands), as these concepts were measured using the corresponding scales from the well-validated Job Content Questionnaire (Karasek et al. 1998). Also, job insecurity seems rather well reflected by the measurement of both cognitive and affective job insecurity (Probst 2003). In addition, similar measures for autonomy, task demands and job insecurity are strongly related to health and well-being measures (Cheng and Chan 2008; Häusser et al. 2010; Sverke et al. 2002).

Therefore, we argue that this finding may be explained by a healthy worker effect, in that healthy workers are the most likely to seek and gain (permanent) employment, while unhealthy workers may become ‘trapped’ into temporary employment or even be drawn into unemployment (M. Virtanen et al. 2005). This explanation finds support in several studies among fixed-term workers, demonstrating that good health, low psychological distress and high work satisfaction increase the chance on future permanent employment (Virtanen et al. 2002), and that non-optimal health increases the chance of becoming unemployed (P. Virtanen et al. 2005). To complicate matters, this explanation is challenged by a recent Belgian study which failed to find evidence of such selection processes (De Cuyper et al. 2009). This underlines the need for further research in this area. Secondly, not all contract differences in work-related attitudes could be fully attributed to differences in the quality of working life and job insecurity. Therefore, other possible important determinants of temporaries’ work-related attitudes warrant attention as well, such as positive elements of temporary employment (e.g. flexibility); expectations and preferences regarding employment contract, occupation and workplace; and, related to this, motives for being temporary employed (e.g. to obtain permanent employment or to become more flexible) (Aronsson and Göransson 1999; De Cuyper et al. 2008; De Cuyper and De Witte 2006; Tan and Tan 2002).

Practical implications

The current study found that agency workers, but not on-call workers, constitute a risk group for health and work attitudinal problems in the Netherlands. Especially, the large share of temporary workers having (1) high-strain jobs and those having (2) passive jobs may be at risk of entrapment in precarious employment, and even unemployment. High-strain work may lead to health and well-being problems (Karasek 1979; Häusser et al. 2010), whereas passive workers may have fewer learning opportunities (Van der Doef and Maes 1999), which may lower their employability. Therefore, measures aimed at improving the quality of working life are needed. In combination with measures targeting job insecurity, they may be effective in reducing contract differences in work-related attitudes. In order to improve the quality of working life among temporary workers, the latter could better be treated as primary segment workers (e.g. in terms of salary, career opportunities, work–time control and fringe benefits). Especially since 70% of the Dutch employers report small to large differences in the way they treat their temporary versus their permanent personnel, which often means better career and training opportunities among the latter (Isaksson et al. 2010). Furthermore, a longitudinal study showed a reduction in job insecurity after acquiring permanent, and thus job secure work (Virtanen et al. 2003). Similar results may be obtained by offering temporary workers better work security guarantees (Bryson et al. 2009).

Strengths and limitations

The most important limitation of the current study is its cross-sectional design, meaning that no causal inferences concerning the associations between employment contracts and the quality of working life, job insecurity, health and work-related attitudes can be drawn. It should be noted that the causal direction of the associations among employment contract, health and work-related attitudes may well be reversed, as it is unlikely that employees with (chronic) health and well-being problems will easily find permanent employment. Secondly, we only measured task demands and autonomy to assess the quality of working life, whereas other job characteristics, such as social support, may also be of importance (Kompier 2003). Finally, this study employed a sample of Dutch employees only. In some respects, there are large differences within the European Union, for example with regard to the number of temporary workers, employment protection legislation with regard to permanent and temporary contracts, job quality and job insecurity (European Commission 2008; Leschke and Watt 2008). Therefore, the degree to which our findings can be generalised to other countries is unknown.

The strongest point of the current study is its large and representative national sample. This allowed us to differentiate among four types of temporary work, including agency and on-call work, which are not always systematically separated (e.g. Kompier et al. 2009). A second asset is our focus on two different mechanisms (quality of working life and job insecurity) that may theoretically account for contract differences in health and work-related attitudes. We also used valid operationalisations to measure both concepts. In line with Probst (2003), we measured job insecurity as a ‘rich’ concept, including both cognitive job insecurity (i.e. perceived chance of job loss) and affective job insecurity (i.e. worry about job loss). We also focused on the combination of task demands and autonomy. This gave us the opportunity to assess, within each contract type, the proportion of jobs with four theoretically relevant combinations of job characteristics, both positive and negative. Finally, we did not operationalise Karasek’s four job types by a rough division of autonomy and task demands (e.g. by means of a crude median split), but based our division on substantive grounds, that is, on absolute answer category labels, which more accurately correspond to the categorisation of ‘low’ versus ‘high’ control and demands.

Future research

Some recommendations for future research are the following. First, the current study showed much diversity in the quality of working life and job insecurity among temporary workers. Therefore, future research should search for specific risk groups for health and well-being problems by focusing on temporary workers, especially agency workers, with a low quality of working life and high job insecurity. Secondly, on-call work proved to be a distinct form of temporary employment. Therefore, future research should separate on-call work from other forms of temporary employment and should investigate the profile(s) of these workers more extensively. Thirdly, the quality of working life and job insecurity acted somewhat differently in explaining health and work-related attitudinal differences between contract types. Thus, future research should distinguish between these two factors in the context of employment contracts, most notably in relation to employability and turnover intention. Finally, longitudinal research is needed to test whether employment contracts and health and work-related attitudes affect each other reciprocally. To this aim, we must study different career paths, not only in terms of contract transitions and transitions between employment and unemployment (e.g., Kompier et al. 2009; P. Virtanen et al. 2005), but also regarding quality of working life and job insecurity. In this way, we can discover which type of work leads to health and attitudinal problems (and eventually to unemployment), and which type of work serves as a stepping stone to healthier work.

References

Aronsson G, Göransson S (1999) Permanent employment but not in a preferred occupation: psychological and medical aspects, research implications. J Occup Health Psychol 4:152–163

Aronsson G, Gustafsson K, Dallner M (2002) Work environment and health in different types of temporary jobs. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 11:151–175. doi:10.1080/13594320143000898

Atkinson J (1984) Manpower strategies for flexible organizations. Pers Manage 16:28–31

Auer P, Cazes S (2000) The resilience of the long-term employment relationship: Evidence from the industrialized countries. Int Labour Rev 139:379–408. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2000.tb00525.x

Becker GS (1993) Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education, 3rd edn. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Benach J, Gimeno D, Benavides FG, Martínez JM, Del Mar Torné M (2004) Types of employment and health in the European Union: changes from 1995 to 2000. Eur J Public Health 14:314–321. doi:10.1093/eurpub/14.3.314

Blatter BM, Bongers PM, Kraan KO, Dhondt S (2000) RSI-klachten in de werkende populatie. De mate van vóórkomen en de relatie met beeldschermwerk, muisgebruik en andere ICT gerelateerde factoren [RSI complaints in the working population. The prevalence and relationship with computer and mouse use and other ICT-related factors]. TNO Arbeid, Hoofddorp

Brown S, Sessions JG (2003) Earnings, education, and fixed-term contracts. Scot J Polit Econ 50:492–506

Bryson A, Cappellari L, Lucifora C (2009) Workers’ perceptions of job insecurity: do job security guarantees work? Labour 23(Suppl 1):177–196

CBS (2003) Permanent Onderzoek Leefsituatie (POLS) Gezondheid 2004 [Permanent living conditions and health survey 2004]. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, Heerlen

Cheng GHL, Chan DKS (2008) Who suffers more from job insecurity? A meta-analytic review. Appl Psychol Int Rev 57:272–303. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00312.x

Ciett (2010) The agency work industry around the world. International Confederation of Private Employment Agencies, Brussels

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Erlbaum, Hillsdale

Connelly CE, Gallagher DG (2004) Emerging trends in contingent work research. J Manage 30:959–983. doi:10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.008

De Cuyper N, De Witte H (2006) Autonomy and workload among temporary workers: their effects on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, life satisfaction, and self-rated performance. Int J Stress Manage 13:441–459. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.13.4.441

De Cuyper N, De Jong J, De Witte H, Isaksson K, Rigotti T, Schalk R (2008) Literature review of theory and research on the psychological impact of temporary employment: towards a conceptual model. Int J Manag Rev 10:25–51. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2007.00221.x

De Cuyper N, Notelaers G, De Witte H (2009) Transitioning between temporary and permanent employment: a two-wave study on the entrapment, the stepping stone and the selection hypothesis. J Occup Organ Psychol 82:67–88. doi:10.1348/096317908X299755

De Witte H (1999) Job insecurity and psychological well-being: review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 8:155–177. doi:10.1080/135943299398302

De Witte H, Näswall K (2003) `Objective’ vs `Subjective’ job insecurity: consequences of temporary work for job satisfaction and organizational commitment in four European countries. Econ Ind Democr 24(2):149–188. doi:10.1177/0143831X03024002002

European Commission (2008) Employment in Europe 2008. European Commission, Brussels

Eurostat (2011a) Employees with a contract of limited duration (annual average). http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tps00073&plugin=1. Accessed 6 Oct 2011

Eurostat (2011b) Temporary employees by sex, age groups and highest level of education attained (1000). http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=lfsq_etgaed&lang=en. Accessed 3 May 2011

Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Stansfeld SA, Marmot MG (2002) Effects of chronic job insecurity and change in job security on self reported health, minor psychiatric morbidity, physiological measures, and health related behaviours in British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. J Epidemiol Commun Health 56:450–454. doi:10.1136/jech.56.6.450

Ferrie JE, Westerlund H, Virtanen M, Vahtera J, Kivimäki M (2008) Flexible labor markets and employee health. Scand J Work Environ Health (Suppl 6):98–110

Goudswaard A, Andries F (2002) Employment status and working conditions. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Luxembourg

Goudswaard A, Dhondt S, Kraan K (1998) Flexibilisering en Arbeid in de Informatie-maatschappij; werknemersvragenlijst, bestemd voor werknemers van organisaties die deelnemen aan het SZW-Werkgeverspanel 1998 [Flexibilization and work in the information society, employee questionnaire for employees of organizations participating in the SZW employers panel 1998]. TNO Arbeid, Hoofddorp

Häusser JA, Mojzisch A, Niesel M, Schulz-Hardt S (2010) Ten years on: A review of recent research on the Job Demand-Control (-Support) model and psychological well-being. Work Stress 24:1–35. doi:10.1080/02678371003683747

Hellgren J, Sverke M (2003) Does job insecurity lead to impaired well-being or vice versa? Estimation of cross-lagged effects using latent variable modelling. J Organ Behav 24:215–236. doi:10.1002/job.184

Hudson K (2007) The new labor market segmentation: labor market dualism in the new economy. Soc Sci Res 36:286–312. doi:10.1080/02678371003683747

Isaksson K, Peiró JM, Bernhard-Oettel C, Caballer A, Gracia FJ, Ramos J (2010) Flexible employment and temporary contracts: the employer’s perspective. In: Guest DE, Isaksson K, De Witte H (eds) Employment contracts, psychological contracts, and employee well-being. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 45–64

Jahoda M (1982) Employment and unemployment: a social-psychological analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kalleberg AL (2003) Flexible firms and labor market segmentation: effects of workplace restructuring on jobs and workers. Work Occup 30:154–175. doi:10.1177/0730888403251683

Karasek RA (1979) Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q 24:285–308

Karasek R (1985) Job Content Questionnaire and user’s guide. University of Massachusetts, Department of Work Environment, Lowel

Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B (1998) The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol:322–355. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.3.4.322

Kawachi I (2008) Globalization and workers’ health. Ind Health 46:421–423. doi:10.2486/indhealth.46.421

Kinnunen U, Feldt T, Mauno S (2003) Job insecurity and self-esteem: evidence from cross-lagged relations in a 1-year longitudinal sample. Pers Individ Dif 35:617–632. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00223-4

Kivimäki M, Vahtera J, Virtanen M, Elovainio M, Pentti J, Ferrie JE (2003) Temporary employment and risk of overall and cause-specific mortality. Am J Epidemiol 158:663–668. doi:10.1093/aje/kwg185

Kompier M (2003) Job design and well-being. In: Schabracq MJ, Winnubst JAM, Cooper CL (eds) Handbook of work and health psychology. Wiley, West Sussex, pp 429–454

Kompier M, Ybema JF, Janssen J, Taris T (2009) Employment contracts: cross-sectional and longitudinal relations with quality of working life, health and well-being. J Occup Health 51:193–203. doi:10.1539/joh.L8150

Koppes LLJ, De Vroome EMM, Mol MEM, Janssen BJM, Van den Bossche SNJ (2009) Nationale Enquête Arbeidsomstandigheden 2008 [The Netherlands working conditions survey 2007: methodology and overall results]. TNO Work and Employment, Almere

Lau B, Knardahl S (2008) Perceived job insecurity, job predictability, personality, and health. J Occup Environ Med 50:172–181. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e31815c89a1

Layte R, O’Connell PJ, Russell H (2008) Temporary jobs in Ireland: does class influence job quality? Econ Soc Rev 39:81–104

Leschke J, Watt A (2008) Job quality in Europe. ETUI-REHS, Brussels

Letourneux V (1998) Precarious employment and working conditions in Europe. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Luxembourg

Parent-Thirion A, Macías EF, Hurley J, Vermeylen G (2007) Fourth European working conditions survey. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Luxembourg

Parker SK, Griffin MA, Sprigg CA, Wall TD (2002) Effect of temporary contracts on perceived work characteristics and job strain: a longitudinal study. Pers Psychol 55:689–719. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2002.tb00126.x

Probst TM (2003) Development and validation of the job security index and the job security satisfaction scale: a classical test theory and IRT approach. J Occup Organ Psychol 76:451–467. doi:10.1348/096317903322591587

Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C, Jackson SE (1996) Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS). In: Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP (eds) MBI manual, 3rd edn. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto

Sverke M, Hellgren J, Näswall K (2002) No security: a meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. J Occup Health Psychol 7:242–264. doi:10.1037//1076-8998.7.3.242

Tan HH, Tan CP (2002) Temporary employees in Singapore: what drives them? J Psychol 136:83–102. doi:10.1080/00223980209604141

Van der Doef M, Maes S (1999) The job demand-control(-Support) model and psychological well-being: a review of 20 years of empirical research. Work Stress 13:87–114. doi:10.1080/026783799296084

Verboon FC, Feyter MG, Smulders PGW (1999) Arbeid en zorg, inzetbaarheid en beloning: het werknemersperspectief [Work and care, employability and reward: the employee perspective]. TNO Arbeid, Hoofddorp

Verhulp E, Beltzer RM, Boonstra K, Christe D, Riphagen J (2002) Flexibele arbeidsrelaties [Flexible employment relations]. Kluwer, Deventer

Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J (2002) Selection from fixed term to permanent employment: prospective study on health, job satisfaction, and behavioural risks. J Epidemiol Community Health 56:693–699. doi:10.1136/jech.56.9.693

Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, Ferrie JE (2003) From insecure to secure employment: changes in work, health, health related behaviours, and sickness absence. Occup Environ Med 60:948–953. doi:10.1136/oem.60.12.948

Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, Joensuu M, Virtanen P, Elovainio M (2005) Temporary employment and health: a review. Int J Epidemiol 34:610–622. doi:10.1093/ije/dyi024

Virtanen P, Vahtera J, Kivimäki M, Liukkonen V, Virtanen M, Ferrie J (2005) Labor market trajectories and health: a four-year follow-up study of initially fixed-term employees. Am J Epidemiol 161:840–846. doi:10.1093/aje/kwi107

Virtanen P, Janlert U, Hammarström A (2011) Exposure to temporary employment and job insecurity: a longitudinal study of the health effects. Occup Environ Med 68(8):570–574. doi:10.1136/oem.2010.054890

Waenerlund AK, Virtanen P, Hammarström A (2011) Is temporary employment related to health status? Analysis of the Northern Swedish Cohort. SPUB. doi:10.1177/1403494810395821

Zeller RA, Carmines EG (1980) Measurement in the social sciences: the link between theory and data. Cambridge University Press, New York

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wagenaar, A.F., Kompier, M.A.J., Houtman, I.L.D. et al. Can labour contract differences in health and work-related attitudes be explained by quality of working life and job insecurity?. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 85, 763–773 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0718-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0718-4