Abstract

Purpose

To investigate (a) differences in work characteristics and (b) determinants of job satisfaction among employees in different age groups.

Methods

A cross-sectional questionnaire was filled in by 1,112 university employees, classified into four age groups. (a) Work characteristics were analysed with ANOVA while adjusting for sex and job classification. (b) Job satisfaction was regressed against job demands and job resources adapted from the Job Demands-Resources model.

Results

Statistically significant differences concerning work characteristics between age groups are present, but rather small. Regression analyses revealed that negative association of the job demands workload and conflicts at work with job satisfaction faded by adding job resources. Job resources were most correlated with more job satisfaction, especially more skill discretion and more relations with colleagues.

Conclusions

Skill discretion and relations with colleagues are major determinants of job satisfaction. However, attention should also be given to conflicts at work, support from supervisor and opportunities for further education, because the mean scores of these work characteristics were disappointing in almost all age groups. The latter two characteristics were found to be associated significantly to job satisfaction in older workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In most of the 30 countries joint in OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), the mean age of workers increases as a result of demographic and social trends (Keese et al. 2006). Birth cohorts since the 1960s are smaller than previous ones, and nowadays a large proportion of the youngest age group (15–25 years) in the labour force is still in education. As an additional effect of these trends, the number of available workers will diminish in the next decades. Estimations in the Netherlands for 2025, compared to 2008, show that the number of persons available for work will decrease by 4.1% (around 340,000 employees) (http://www.statline.nl). Comparable trends are predicted for other Western countries. Participation of a larger part of the people who potentially are able to work is necessary to prevent scarcity on the labour market. The European Council in Lisbon (in 2000) and Stockholm (in 2001) have set ambitious targets to be reached by 2010: to increase the general employment rate to 70% and the employment rate of older workers (55 and older) to 50% (Hutsebaut 2005). Encouraged by these targets and urged by the predicted scarcity in the labour market, many governments have enacted, among others, measures to discourage early retirement, in order to increase labour force participation (Hutsebaut 2005). In the Netherlands, these measures are rather successful: over the past 15 years, the participation of older workers (aged between 55 and 64) has increased from the all-time low of 24% in 1993 (Wilthagen 2004) to 47% in 2008 (Janssen and Souren 2009).

Retirement at a more advanced age will contribute to the trend that a larger number of employees will be of 55 up to 65 years. For a good HRM and occupational health policy it is important to get a better picture of how people in this age group perceive their work and to evaluate what contributes to their job satisfaction, compared to employees in younger age groups. The latter is also important because low job satisfaction is one of the factors that affect the intention to leave (Irvine and Evans 1995; Karatepe 2007; McCarthy 2007) and to early retirement (Sibbald et al. 2003). Moreover, Faragher et. al. (2005) concluded from a meta-analysis that job satisfaction influences the health and well-being of workers.

This article addresses employees’ work characteristics, and the relationships between work characteristics and job satisfaction. Two research goals were addressed:

-

To obtain more insight into the employees’ point of view concerning some work characteristics and job satisfaction, after classification in four age groups in order to investigate the differences between these age groups.

-

To find out which work characteristics are associated with job satisfaction in four different age groups.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed on data sampled in an online survey on employability and workability among the employees at a Dutch university (both staff and faculty). We compared age differences in various work characteristics in univariate analyses, and we regressed job satisfaction onto work characteristics in the multivariate analyses. On account of current (negative) beliefs about older workers (Chiu et al. 2001; Visser et al. 2003; Remery et al. 2003; Peeters et al. 2005; Henkens 2005), we expect that the scores of the oldest age group will be substantially lower than those of younger age groups. Furthermore, we expect that differences in determinants of job satisfaction will be found due to differences in career, position, work-life balance, etc. (Donders et al. 2007).

Theoretical background

Many studies have shown that work characteristics can have a profound impact on employee well-being (e.g. job strain, work engagement and job satisfaction). Although a great deal of research has been done into the determinants of job satisfaction (Oshagbemi 2003; Lu et al. 2005; Horton 2006; Chen et al. 2006), so far less attention has been paid to differences between age groups.

Job satisfaction is known to be affected by multiple factors. The Job Demands-Resources Model (JD-R model) (Demerouti et al. 2001) is a theoretical model that attempts to provide insight into the relationships between psychosocial work characteristics on the one hand and well being on the other. According to the JD-R model, the characteristics of work environment can be classified into two general categories: job demands and job resources. Job demands are those physical, social or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical and/or psychological effort and are therefore associated with physical and/or psychological costs. Job resources are those physical, social or organizational aspects of the job that (a) are functional in achieving work-related goals, (b) reduce job demands and the associated physical and/or psychological effects and (c) stimulate personal growth and development (Demerouti et al. 2001). The JD-R model may incorporate different demands and resources, depending on the context under study. Though the model was originally developed to explain burnout, it is also applicable to clarify well being at work and job satisfaction (Van Ruysseveldt 2006). Robustness of the model was ascertained (Llorens et al. 2006).

The JD-R model predicts that when high job demands are experienced, emotional exhaustion increases and job satisfaction will decrease. Job resources, however, are associated with a reduction in emotional exhaustion and an increase in job satisfaction (Demerouti et al. 2001; Van Ruysseveldt 2006). So, we expect that especially job resources will correlate with job satisfaction in the multivariate models.

On theoretical grounds (Van Ruysseveldt 2006), four job demands and five job resources were selected for the multivariate analyses. The job demands included problems with workload, conflicts at work, work-home facilitation and “able to relax sufficiently at home from job demands”. Many studies have reported a negative relation between workload and conflicts at work, and job satisfaction (Quine 1999; Van der Doef and Maes 2000; Biron et al. 2008). Work-family conflict and job satisfaction are strongly related (Kossek and Ozeki 1998). Work-to-life balance is one of the stressors strongly associated with reported physical and psychological health (Tytherleigh et al. 2005; Kinman 2008; Kinman and Jones 2008). Furthermore, the extent to which someone can relax sufficiently at home from job demands is considered a job demands measure but has not been subject to research yet.

Five job resources were included: skill discretion, autonomy, support from supervisor, relation with colleagues and opportunities for further education. Skill discretion refers to the breadth of skills used by the employee on the job, and it is positively associated with job satisfaction (Iiacqua 1995; Van der Doef and Maes 2000). Autonomy refers to the employees’ authority to make decisions regarding one’s tasks. It is an important aspect of job control. Relations with colleagues and support from supervisor are beneficial for job satisfaction (Bilimoria et al., 2006). Opportunities for further education are important for employability, and highly associated with job satisfaction (Van Ruysseveldt 2006).

Methods

Respondents

An invitation to participate in an online survey was emailed to all 2,995 employees at a Dutch university. They all had the Dutch nationality and had been employed for at least 1 year. Each respondent was given a personal number which enabled them to fill in the questionnaire online. The 142 employees who did not have a personal e-mail address received a paper version at their home address, but it was also made possible for them to respond online. One reminder was sent (by e-mail or in writing) after 10 days.

A total of 1,297 respondents returned the questionnaire (43%). Age had been filled in by 1,112 respondents, which resulted in 37% usable questionnaires. Comparison with the total population showed that the sample gave a fair reflection with respect to age, unit and ‘job classification’ (faculty versus staff). Differences were present especially among faculty. Slightly more women (37% compared to 33%) and older respondents (≥ 55 years) (23% compared to 18%) returned the questionnaire. Thus, (older) lectures were overrepresented (33% compared to 26%), while (younger) PhD students (20% compared to 25%) and faculty with temporary contracts of employment (34% compared to 43%) were underrepresented.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was based on preliminary research in which interviews were held with stakeholders and two rounds of focus groups to enquire about barriers and factors to support work ability in (older) workers. Subsequently, relevant scales were selected from the questionnaire that is used extensively by “IVA Policy research and advice” in their employee studies (Thunissen and Van der Hoek 2001). Confirmatory factor analyses showed an almost similar classification as can be expected on theoretical grounds (data available on request), with satisfactory reliability which will be presented in the next paragraph. The questionnaire contained scales and items measuring work characteristics (i.e. job demands and job resources) and other relevant scales and items, which we will call ‘other (work) characteristics’.

The outcome measure job satisfaction was assessed using a 7-item scale (α = 0.87) with questions such as “I am satisfied with my job at the moment”, “I enjoy my work” and “I would choose exactly the same job again”.

Workload was obtained by measuring the extent to which the respondents agreed with “all in all, I have problems with workload”.

Conflicts at work was assessed with four items (α = 0.79); e.g. “conflicts are solved easily” (reverse scoring) and “I have conflicts with my colleagues”. Work-home facilitation was assessed with one single item “I can adjust my working hours well in my private life”. “Able to relax sufficiently at home from job demands” was measured with one single item.

Skill discretion was analysed with 5 items (α = 0.85), e.g. “I have enough opportunities within my current job to take on challenging new tasks” and “I can fully use my knowledge and skills during work”. Autonomy was measured with four items (α = 0.81), e.g. “I can determine how to organize my work” and “I can determine my own work pace”. Relation with colleagues was assessed with two items (α = 0.63): “the contact with my colleagues is good” and “I feel respected by my colleagues”).

The support from supervisor scale contained 16 items (α = 0.96), e.g. “my supervisor inspires and motivates me” and “my supervisor regularly discusses opportunities for my personal development”. Opportunities for further education were assessed with three items (α = 0.63): “I receive sufficient opportunities for retraining”, “it is my own responsibility to update the knowledge and skills necessary for my further development” and “the university attaches importance to retraining employees”.

In addition to the aspects from the JD-R model, several other (work) characteristics were assessed. For further exploring differences and similarities concerning workload, two items were analysed: “it is aggravating to have to work longer hours than intended” and “expecting positive results from decreasing workload”. For further exploring social support, “if there is a problem, I can ask someone for help” was included. Appreciation of older workers by the employer was assessed with three items (α = 0.68): “older workers are valued because they are highly experienced”, “older workers are expected to be less productive than younger employees” (reverse scoring) and “knowledge and experience are being passed on from older to younger employees”. Appreciation and feedback were separately assessed with “I receive enough appreciation for my efforts” and “I receive enough feedback”. Contentment with remuneration was assessed with three items. (α = 0.89): “my salary is suitable for the job”, “my salary is in accordance with my knowledge and skills” and “my salary prospects are good”). “Readiness to join in further education” included two items (α = 0.81): “I am prepared to retrain” and “I am prepared to invest time in retraining”. Furthermore, following items were included: “I am ready to take on new tasks all the time”, “I expect positive results from regular attention to career and development opportunities”, “I expect positive results from clarifying the work objectives”. The ‘positive results’ intended by these questions were job satisfaction, employability and optimal performance.

These ‘other (work) characteristics’ were not included in the multivariate analyses as they were not included in the research model by Van Ruysseveldt (2006). However, literature shows that they are associated with job satisfaction (Chen et al. 2006; Bilimoria et al. 2006; Winefield et al. 2008) and therefore of interest to get better insight into differences and similarities between the age groups.

Control variables included into the multivariate models are “presence of chronic disease”, “normal job performance is impeded by poor health”, sex and job classification [“faculty” (professors, lectures and researchers) versus “staff” (all other employees)]. The first two variables are included since the prevalence of chronic disease and poor health increases with age. Personal characteristics included age, the number of working hours per week, contract of employment (temporary or permanent), term of appointment, number of years in the same position and having children at home. They were all assessed with one single item.

Most items were scored on a 5-point scale either to indicate the level of agreement with a statement (1 completely disagree, 5 completely agree) or to measure the extent to which a statement applied to the respondent (1 not at all, 5 to a large extent). An exception was “normal job performance is impeded by poor health”, which was assessed with a 4-point answering scale (1 not/hardly, 4 greatly). Furthermore, a few items simply required a yes or no.

For all scales, a scale score was calculated by averaging the item scores. In all scales and items, higher scores mean more agreement with the proposition. Thus, higher scores for skill discretion means that the respondents experience more skill discretion (desirable), whereas higher scores for conflicts at work means that the respondents are confronted with more conflicts at work (which is undesirable).

In the statements with a positive formulation, mean scores higher than 3.5 were considered to be satisfactory, because this level suggested that the relevant work conditions were solid. In the negative formulations, this applied to mean scores of 2.5 and lower. In addition, the portion of the respondents with satisfactory scores was calculated. This means the percentages of workers with satisfactory mean scale scores (i.e. >3.5 or ≤2.5) or the percentages workers with satisfactory answers for items [i.e. either agree to moderate or to large extent or (completely) agree].

Analyses

Analyses were conducted on four age groups: younger than 35, 35–44, 45–54 and 55 years and older. This choice of classification was based on the probable major differences in home situation (e.g. younger versus older children at home) and work experience (e.g. duration of professional tenure) between the age groups that were likely to interfere with work characteristics and job satisfaction (Lynn et al. 1996). Data were analysed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Differences in personal characteristics were analysed with χ2-tests (Table 1). “Normal job performance is impeded by poor health” was dichotomized. Impediment was assumed when the respondents indicated to agree ‘slightly’, ‘moderately’ or ‘greatly’ with the proposition.

In order to answer the first research question, factorial ANOVA was used to test the correlation between age and several work characteristics while adjusting for sex and job classification (Table 2).

In order to answer the second research question, blockwise linear regression analyses were used in each age group separately to investigate variables associated with job satisfaction (Table 3). First, before including into the regression analyses, the answers of four items were dichotomized; normal job performance is impeded by poor health, problems with workload, work-home facilitation, “able to relax sufficiently at home from job demands”. Agreement with the statement (completely agree, agree and neither agree nor disagree) was appointed a one, while disagreement (disagree and completely disagree) was appointed a zero. In normal job performance is impeded due to poor health, an one was assigned to agreement (slightly, moderately and greatly) and a zero to disagreement (not/hardly). Secondly, we checked multicollinearity by computing tolerances and variance inflation factors (VIFs). Following the guidelines (Bowerman and O’Connell 1990; Menard 1995), we concluded that there was no reason for concern (adapted from Field 2002) (but available on request). The regression model with the independent variable ‘job satisfaction’ comprised three blocks. First, the control variables (presence of chronic disease, normal job performance is impeded by poor health, sex and job classification) were entered. Next, into the second block, job demands (problems with workload, conflicts at work, work-home facilitation and “able to relax sufficiently at home from job demands”) were entered. Finally, into the third block, job resources (skill discretion, autonomy, support from supervisor, relation with colleagues and opportunities for further education) were entered. Statistical significance was set at α ≤ 0.05.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the personal characteristics per age group. The percentage of women in the oldest age group (26.6%) was significantly smaller than that in the other groups. In the whole study population, only 13% reported to have chronic disease. The prevalence differed significantly between the age groups. Occurrence of “normal job performance impeded by poor health” varied (not significantly) from 12.7% in the 35- to 44-year olds to 20.2% in the oldest age group. Further analysis showed that this impediment had other causes than chronic disease in about 50–60% of the cases in the three oldest age groups. In the youngest age group, only about one quarter of the cases was attributable to chronic disease. In all the age groups, significantly more men than women had full-time jobs.

Work characteristics in different age groups

In Table 2, sex and job classification adjusted mean scores (i.e. estimated marginal means) (range 1–5) and their standard errors are presented per age group. Also the percentages of employees with satisfactory scores are shown.

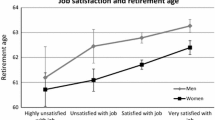

Job satisfaction had high mean scores in all the age groups. Higher age was associated with more job satisfaction.

Most mean scores for work characteristics differed statistically significantly between the age groups. In all the work characteristics, standard errors of the youngest and the oldest age groups were slightly higher than in the two midst age groups. However, mean scores were almost consistently either satisfactory or disappointing in all the age groups using the cut offs. Six out of the 20 work characteristics shown had disappointing scores in all the age groups. When significant differences between the age groups were present, the youngest age group most often had the most favourable scores and the two midst age groups most often had the least favourable scores. Older workers reported significantly lower scores on ‘readiness to join in further education’ and ‘I am ready to take on new tasks all the time’. In only a few work characteristics, both satisfactory and disappointing mean scores were found, namely in problems with workload, opportunities for further education and “if there is a problem, I can ask someone for help”.

Determinants of job satisfaction

Blockwise multiple regression analyses were performed to identify determinants of job satisfaction in the four age groups separately. F-ratios of all three models were highly significant in all the age groups, except the first model (control variables only) in the youngest age group. Standardized coefficients (Beta) and the percentages of explained variance of each model are shown in Table 3 for each age group separately.

The models show a rather good fit: between 53 and 65% of the variance in job satisfaction was explained. The job demands explain about 15% of the variance in job satisfaction in all the age groups. Addition of the job resources yields an increase of on average 35% of the variance explained.

The second model (control variables and job demands) shows that more problems with workload and more conflicts at work are associated with lower job satisfaction in all the age groups.

In the final models (control variables, job demands and job resources), problems with workload is no longer associated with job satisfaction. Especially, skill discretion and to a lesser extent relation with colleagues are associated with job satisfaction. More skill discretion (i.e. the possibility to use all ones knowledge and skills at work) and better relation with colleagues are associated with more job satisfaction. Among 45- to 54-year olds, more autonomy is also associated with more job satisfaction, while in the oldest age group also opportunities for further education and support from supervisor show a significant positive association.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to explore differences and similarities in work characteristics [i.e. job demands, job resources and other (work) characteristics] between employees divided into four different age groups. In addition, by applying regression analyses, determinants of job satisfaction were investigated as job satisfaction is known to be one of the variables associated with early retirement (Sibbald et al. 2003) and intention to drop-out (Irvine and Evans 1995; Karatepe 2007; McCarthy 2007). Both research questions are discussed separately below.

Differences and similarities in work characteristics

The answer to the first research question is not straightforward. It depends on the way the results are looked at. In 17 out of the 20 work characteristics analysed, mean scores were either satisfying or disappointing in all the age groups (see Table 2). So, concordance was found regarding the mean scores using the chosen cut-offs (>3.5 for positively phrased variables and ≤2.5 for negatively phrased variables, respectively). Nonetheless, the results showed small but statistically significant differences between the four age groups with regard to many work characteristics. In addition, the higher standard errors in both the youngest and the oldest age group indicate larger in-group differences among the youngest and the oldest respondents.

Striking was the fact that mean scores in the youngest age group were almost consistently most favourably, followed by the mean scores of the oldest age group. The youngest age group experienced least workload and best support from supervisor. Two explanations may fit. The youngest workers are relatively inexperienced and starting their career through which they probably have less tasks and responsibilities. Also, many of these workers may be PhD students, whom are clearly assigned a supervisor and who receive relatively much support. Only in skill discretion and in “I expect positive results from clarifying the work objectives”, they had least favourable scores. When work experience grows and tasks are expanded, more possibilities to use skills and knowledge will appear. Older workers scores may reflect their years of experience on the job, which was significantly higher than in the other age groups (see Table 1). It is to be expected that older workers have accomplished many of their goals in working life. This might explain why their mean scores for readiness for further education, “I am ready to take on new tasks all the time” and “I expect positive results from regular attention to career and development opportunities” where least favourable. This tendency that older workers are less enthusiastic to join in further education is also found in other research (Muffels 2003; Ilmarinen 2005). However, supplementary analysis on a separate item from the ‘opportunities for further education’ scale does not support this explanation. Older employees felt significantly more responsible for keeping pace with the new knowledge and skills needed for further development than the workers in the younger age groups (almost 90 vs. about 75%, respectively). This attitude was also found among alumni at a US state university’s School of Business. Age did not appear to be associated with the hours the alumni invested in professional development (Greller 2006).

All in all, the mean scores suggested that working conditions were good. Interesting is that three of the six work characteristics with disappointing scores in all the age groups were related to support and appreciation. Most favourable work characteristics were reported by the youngest and the oldest age groups. This does not correspond with the negative beliefs, many employers (especially the younger ones) were found to have about older employees (Chiu et al. 2001; Visser et al. 2003; Remery et al. 2003; Peeters et al. 2005; Henkens 2005), although not all the research confirmed this (Munnel et al. 2006). For instance, older workers were expected to be less able to cope with a heavy workload (Visser et al. 2003) and hard to (re)train, while depletion of professional knowledge and skills were considered to be the most important obstacles against employing older workers (Taylor and Walker 1998). Our results show that statistical differences are present, but that these differences are small. For instance, readiness to join in further education is significantly lower among older workers, but still satisfactory (more than 60% satisfactory mean scores in the oldest age group). Also, significantly lower percentages of older employees stated to be “ready to take on new tasks all the time”, but still almost 60% of the older workers answered this item confirmative.

Many research demonstrated the relationship between employee age and job satisfaction. However, the nature of this relationship, whether linear or curvilinear, remains unsettled (Oshagbemi 2003). In our data we found a significant positive correlation between age and job satisfaction, indicating that job satisfaction increases with age. The fact that the youngest workers had least favourable scores on job satisfaction is remarkable, since they reported most favourable work characteristics.

In order to understand the rather small differences between the age groups, we have to consider them in the light of the possible dual selection within the study population. First, in a university setting—but probably especially within the faculty—only the workers who prove to have sufficient mental and physical capacities are offered permanent jobs. In addition, only those with a job that suits them, including the necessary job-related adjustments, will stay on during their further career. Second, ageing is often accompanied by higher prevalence of chronic disease, which may lead to early drop-out (De Boer et al. 2004) and thereby create a ‘healthy worker effect’ (Eisen et al. 2006). It is likely that the oldest age group contains a disproportionately high number of healthy and motivated employees with well-suited jobs. However, the total proportion of respondents with chronic diseases in this study, which was 13%, was considerably smaller than in the Dutch population aged between 15 and 65 years (namely, 30%) (De Klerk 2000). In our sample, we found only small differences in the health measures ‘presence of chronic disease’ and ‘normal job performance impeded by poor health’ between the four age groups (see Table 1). So, predominantly healthy workers were found in all the age groups. But, in the near future, due to public and company measures reducing early retirement and limiting possibilities for entering disability pensions, managers may need to employ more chronically ill people and also retain their less satisfied older employees. Such developments will probably reduce the “healthy worker effect” and increase the differences in health between the age groups.

Determinants of job satisfaction in the different age groups

Job satisfaction was regressed onto several job demands and job resources derived from the JD-R model in four different age groups. The second objective of the study was to find out which of the work characteristics are associated with job satisfaction in each of them. As, to our knowledge, no research has been conduced into determinants of job satisfaction in different age groups, we can only compare our results to those from research that did not focus on age-related differences.

In block 2, conflicts at work was significantly associated with job satisfaction in all the age groups, but in the final model this was the case in only the youngest age group. Their inexperience and the fact that relatively many of them are PhD student may result in more dependency. This may contribute to the stronger correlation between conflicts at work and job satisfaction in the youngest age group than the other age groups.

Factors of major importance to job satisfaction in the final models were the extent to which personal skills could be used at work (‘skill discretion’) and the relations with colleagues. Skill discretion was often found to be one of the factors most associated with job satisfaction in other studies among highly skilled professionals as well, i.e. in university faculty (Iiacqua 1995), in health care employees (Van der Doef and Maes 2000; Pomaki et al. 2004; Akerboom and Maes 2006) and in general practitioners (McGlone and Chenoweth 2001; Akerboom and Maes 2006), but not always (Smerek and Peterson 2007).

It is remarkable that especially in the oldest employees support from supervisor is correlated with job satisfaction. Older and more experienced workers may be deprived of support from their supervisor since they are expected to work independently, while support from supervisor is important for job satisfaction (Robson et al. 2005; Callister 2006), apparently irrespective of age. It is therefore alarming that disappointing mean scores were found for support from supervisor in all age groups (see Table 2).

The correlation between job satisfaction and opportunities for further education may partly be explained by the perception of the provision of further training by older workers. In a study in New Zealand on skilled workers, older workers perceived the supply of extra training as a signal from the employer that they are still being taken seriously and as valuable employees (Gray and McGregory 2003).

The final regression models show a rather good fit with 53–65% of the variance explained. As expected most variance in job satisfaction was explained by job resources (on average 35% unique variance). This finding is consistent with former research using the JD-R model to explain well being (Demerouti et al. 2001; Van Ruysseveldt 2006). Well-being factors such as job satisfaction are most strongly associated with the availability of positive work characteristics. Job resources included into the model seem to reduce the disadvantageous effects of job demands such as workload and conflicts at work. Moreover, in the oldest age group, the adverse consequence of chronic disease for job satisfaction has been reduced completely.

Methodological considerations

In this study, all the respondents were employees at a university, a work setting with specific characteristics. This has implications for generalization because autonomy is often very broad in university populations and the majority of jobs are “white collar” (Donders et al. 2003).

As in many other research into university personnel, the results of our study concerned faculty and staff together. This was justified because we focused on differences and similarities between age groups. Also, we assumed that job classification (faculty or staff) would add relatively little explanatory information in linear regression analyses beyond perceived work characteristics (Bültmann et al. 2001). Moreover, a large proportion of the university staff were highly educated people with professional job titles (Donders et al. 2003). However, being a faculty employee appeared to be associated with greater job satisfaction in the 35- to 44-year olds and the oldest age group (see Table 3).

According to (Baruch 1999) our response (37%) can be considered acceptable. However, the proportion of youngest employees was lower than in the university population (17 and 24%, respectively). The same applied to the workers with temporary contracts (16% in the sample and 23% in the population, respectively), who are predominantly found in the youngest age group. We suppose that younger employees were less motivated to participate in a study on the employability and workability of older workers. We do not believe that especially satisfied or only dissatisfied young workers engaged in the study.

Owing to the cross-sectional design of our study, we could not establish causality.

Conclusion

The results of this study show that differences concerning work characteristics between age groups are present, but rather small. The two midst age groups (35–44 and 45–54 years of age, respectively) had least favourable mean scores in most work characteristics.

For HRM and occupational health professionals it is of interest to know what contributes most to job satisfaction and in which work characteristics most gain is to be expected when subject to improvement projects. Following our results, skill discretion and relations with colleagues play a major role. Both work characteristics contributed strongly to the variance in job satisfaction. Also, attention should be given to support from supervisor and opportunities for further education. In all age groups, the mean scores of these work characteristics were disappointing. Moreover, these factors contribute significantly to the job satisfaction of older workers.

References

Akerboom S, Maes S (2006) Beyond demand and control: the contribution of organizational risk factors in assessing the psychological well-being of health care employees. Work Stress 20(1):21–36

Baruch Y (1999) Response rate in academic studies—a comparative analysis. Hum Relat 52(4):421–438

Bilimoria D, Perry S, Liang X, Stoller E, Higgins P, Taylor C (2006) How do female and male faculty members construct job satisfaction? The roles of perceived institutional leadership and mentoring and their mediating processes. J Technol Transf 31(3):355–365

Biron C, Brun JP, Ivers H (2008) Extent and sources of occupational stress in university staff. Work J Prev Assess Rehabil 30(4):511–522

Bowerman BL, O’Connell RT (1990) Linear statistical models: an applied approach. Duxbury, Belmont

Bültmann U, Kant IJ, van Amelsvoort LGPM, van den Brandt PA, Kasl SV (2001) Differences in fatigue and psychological distress across occupations: results from the Maastricht cohort study of fatigue at work. J Occup Environ Med 43(11):976–983

Callister R (2006) The impact of gender and department climate on job satisfaction and intentions to quit for faculty in science and engineering fields. J Technol Transf 31(3):367–375

Chen S, Yang C, Shiau J, Wang H (2006) The development of an employee satisfaction model for higher education. TQM Mag 18(5):484–500

Chiu WCK, Chan AW, Snape E, Redman T (2001) Age stereotypes and discriminatory attitudes towards older workers: An East-West comparison. Hum Relat 54(5):629–661

De Boer AGEM, Van Beek JC, Durinck J, Verbeek JHAM, Van Dijk FJH (2004) An occupational health intervention programme for workers at risk for early retirement; a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med 61(11):924–929

De Klerk MMY (2000) Aantal chronisch zieken en gehandicapten [in Dutch; number of chronically ill and disabled]. In: De Klerk MMY (ed) Rapportage ouderen 2000. Arbeidsmarktpositie en financiële situatie van mensen met beperkingen en/of chronische ziekten [in Dutch; report on the disabled 2000]. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau

Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB (2001) The Job Demands-Resources Model of burnout. J Appl Psychol 86(3):499–512

Donders NCGM, Van der Gulden JWJ, Furer JW, Tax B, Roscam Abbing EW (2003) Work stress and health effects among university employees. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 76(8):605–613

Donders NCGM, Bos JT, van der Gulden JWJ (2007) Associations between sick leave and aspects of work and family life in different age groups. Eur J Public Health 17(Suppl 1):236–237

Eisen EA, Wegman DH, O’Neill MS (2006) Epidemiology. In: Levy BS, Wegman DH, Baron SL, Sokas RK (eds) Occupational and environmental health. Recognizing and preventing disease and injury. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Faragher EB, Cass M, Cooper CL (2005) The relationship between job satisfaction and health; a meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med 62105–62112

Field A (2002) Discovering statistics using SPSS for windows. The Cromwell Press Ltd., Trowbridge

Gray L, McGregory J (2003) Human resource development and older workers: stereotypes in New Zealand (abs.). Asia Pac J Hum Resour 41(3):338–353

Greller MM (2006) Hours invested in professional development during late career as a function of career motivation and satisfaction. Career Dev Int 11(6):544–559

Henkens K (2005) Stereotyping older workers and retirement: the managers’ point of view. Can J Aging 24(4):353–366

Horton S (2006) High aspirations: differences in employee satisfaction between university faculty and staff. ARQOL 1(3):315–322

Hutsebaut M (2005) How to reconcile employees’ interest with the increasing older workers employment policies. Eur Pap New Welf (1):116–122

Iiacqua JA (1995) Factors contributing to job satisfaction in higher education. Education

Ilmarinen J (2005) Towards a longer work life! Ageing and the quality of worklife in the European Union. Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Helsinki

Irvine DM, Evans MG (1995) Job satisfaction and turnover among nurses: integrating research findings across studies. Nurs Res 44(4):246–253

Janssen B, Souren M (2009) Naar een arbeidsparticipatie van 80 procent in 2016 [in Dutch, ‘To labour participation of 80 percent in 2016’]. Sociaaleconomische Trends (2):7–13

Karatepe OM (2007) Conflict, exhaustion, and motivation: a study of frontline employees in Northern Cyprus hotels. Int J Hospit Manag 26(3):645–665

Keese M, Hirsch D, Bednarzik R (2006) Live longer, work longer: a synthesis report

Kinman G (2008) Work stressors, health and sense of coherence in UK academic employees. Educ Psychol 28(7):823–835

Kinman G, Jones F (2008) A life beyond work? Job demands, work-life balance and wellbeing in UK academics. J Hum Behav Soc Environ 17(1/2):41–60

Kossek EE, Ozeki C (1998) Work-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: a review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research 17. J Appl Psychol 83(2):139–149

Llorens S, Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB, Salanova M (2006) Testing the robustness of the Job Demands-Resources Model. Int J Stress Manag 13(3):378–391

Lu H, While A, Barriball K (2005) Job satisfaction among nurses: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud 42(2):211–227

Lynn SA, Cao LT, Horn BC (1996) The influence of career stage on the work attitudes of male and female accounting professionals. J Organiz Behav 17135–17149

McCarthy G (2007) Intention to ‘leave’ or ‘stay’ in nursing. J Nurs Manag 15(3):248–255

McGlone SJ, Chenoweth IG (2001) Job demands and control as predictors of occupational satisfaction in general practice. Med J Aust 175(2):88–91

Menard S (1995) Applied logistic regression analysis. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Muffels R (2003) To be employable or not to be? De inzetbaarheid van oudere en jongere werknemers in Nederland en Europa The employability of older and younger workers in the Netherlands and Europe [in Dutch]. In: Ester P, Muffels R, Schippers J (eds) De organisatie en de oudere werknemer. Bussum: Uitgeverij Coutinho

Munnel A, Sass S, Soto M (2006) Employer attitudes towards older workers: survey results

Oshagbemi T (2003) Personal correlates of job satisfaction: empirical evidence from UK universities. Int J Soc Econ 3020(12):1210–1232

Peeters MCW, Nauta A, De Jonge J, Schalk R (2005) De toekomst van oudere werknemers: de revival van een ‘oud’ thema in de arbeids- en organisatiepsychologie [in Dutch; The future of older employees: the revival of an ‘old’ theme in Work and Organizational Psychology]. Gedrag Organisatie 18(6):297–308

Pomaki G, Maes S, ter Doest L (2004) Work conditions and employees’ self-set goals: goal processes enhance prediction of psychological distress and well-being. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 30(6):685–694

Quine L (1999) Workplace bullying in NHS community trust: staff questionnaire survey. BMJ 318(7178):228–232

Remery C, Henkens K, Schippers J, Ekamper P (2003) Managing an aging workforce and a tight labor market: views held by Dutch employers. Popl Res Pol Rev 22(1):21–40

Robson A, Yarrow D, Owen J (2005) Does quality drive employee satisfaction in the UK learning sector? Int J Qual Reliab Manag 22(5):465–484

Sibbald B, Bojke C, Gravelle H (2003) National survey of job satisfaction and retirement intentions among general practitioners in England. BMJ 326(22):73–79

Smerek RE, Peterson M (2007) Examining Herzberg’s theory: improving job satisfaction among non-academic employees at a university. Res High Educ 48(2):229–250

Taylor P, Walker A (1998) Employers and older workers: attitudes and employment practices. Ageing Soc 18(6):641–658

Thunissen M, Van der Hoek Th (2001) De personeelsenquête [in Dutch; The employee questionnaire]. Gids voor Personeelsmanagement (4):21–23

Tytherleigh MY, Webb C, Cooper CL, Ricketts C (2005) Occupational stress in UK higher education institutions: a comparative study of all staff categories. High Educ Res Dev 24(1):41–61

Van der Doef MP, Maes S (2000) Do (changes in) job conditions affect health and well-being among nursing home employees? Thesis. Leiden University, Enschede

Van Ruysseveldt J (2006) Psychische vermoeidheid en plezier in het werk bij Vlaamse werknemers [in Dutch; Mental exhaustion and job satisfaction in Flemish workers]. Tijdschrift voor Arbeidsvraagstukken 22(4):328–343

Visser P, Henkens K, Schippers J (2003) Beeldvorming en stereotypering over oudere werknemers [in Dutch; Perception and stereotyping about older workers]. In: Ester P, Muffels R, Schippers J (eds) De organisatie en de oudere werknemer [in Dutch; The organization and the older worker]. Coutinho, Bussum

Wilthagen T (2004) The Netherlands—participation of older workers increases and disability rates go down. EEO, vol 21 http://www.eu-employment-observatory.net

Winefield T, Boyd C, Saebel J, Pagnata S (2008) Update on national university stress study. Aust Univ Rev 50(1):20–29

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Jan Burema for his statistical recommendations after reviewing a previous draft of this manuscript. They also would like to thank Hans Bor for sharing his knowledge on SPSS concerning some part of the calculations.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bos, J.T., Donders, N.C.G.M., Bouwman-Brouwer, K.M. et al. Work characteristics and determinants of job satisfaction in four age groups: university employees’ point of view. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 82, 1249–1259 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-009-0451-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-009-0451-4