Abstract

Purpose

To investigate whether blue-collar employment in the Swedish rubber industry from 1973 onwards had a negative impact on reproductive health.

Methods

Pairs of mother and child, and triads of father–mother–child were obtained through linkage of a cohort of 18,518 rubber factory employees with the Swedish Population Registry. Birth outcomes were obtained from the Medical Birth Register for 17,918 children. For each child, parental employment as blue-collar rubber worker during the pregnancy and sperm maturation period was obtained from work-place records. Children to female food industry workers, in all 33,256, constituted an external reference group.

Results

The sex ratio was reversed, with odds ratio (OR) for having a girl was 1.15 (95% CI 1.02, 1.31) when the mother was exposed. When both parents were exposed, the OR was even higher, 1.28 (95% CI 1.02, 1.62). An increased risk of multiple births was observed when both parents were exposed, with OR 2.42 (95% CI 1.17, 5.01). Children with both maternal and paternal exposure had a reduced birth weight compared to the external reference cohort. After adjustment for smoking (available for births from 1983 onwards), ethnicity and sex, the difference between children (singletons, live births) with maternal and paternal exposure and external referents was −142 g (95% CI −229, −54). The adjusted OR for having a small-for-gestational-age child was 2.15 (95% CI 1.45, 3.18) when the mother was a rubber worker during the pregnancy.

Conclusion

There were clear indications that reproductive outcome was adversely affected in rubber workers. The findings warrant further investigation with refinement of exposure indices and inclusion of other endpoints of reproductive health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Work in the rubber industry may entail exposure to a number of toxic compounds, of which many are carcinogenic or mutagenic. It is well known that work in the rubber industry previously has resulted in enhanced risks for bladder cancer, lung cancer, leukaemia and probably certain other tumor types (Kogevinas et al. 1998), whereas cancer risks in the modern rubber industry are still unrevealed. In contrast to the numerous cancer studies, reproductive health in the rubber industry has been investigated to a minor extent.

Based on a very small material, a suspected enhanced risk for spontaneous abortions and malformations was reported among Swedish female rubber workers (Axelson et al. 1983). A Finnish study based on census-derived job-titles indicated an enhanced risk for spontaneous abortions among wives to rubber workers (Lindbohm et al. 1991). In a similar Canadian study, an increased risk for congenital malformations, although not statistically significant, was observed among infants born to women working in rubber and plastics industries (McDonald et al. 1988). Also, an increased risk for stillbirths, however not statistically significant, has been reported in women working in the rubber, plastics and synthetics industry (Savitz et al. 1989), as well as an increased risk for spontaneous abortions in women in the rubber and plastics production industry (Figa-Talamanca 1984). In two small studies from Cuba and Mexico, rubber workers had, somewhat more aberrant sperm morphology than a control group (de Celis et al. 2000; Rendon et al. 1994), but methodological problems limit the conclusions that can be drawn from these studies.

The present state of knowledge is not sufficient for a firm assessment of risks for the reproductive health in the rubber industry. The chemical work environment has indeed become better in the Swedish rubber industry during the last decades (ExAsRub 2004; de Vocht et al. 2007a, b). Still substantial exposures remain, and we assume that rubber workers are among those Swedish workers, who have the highest exposure levels to substances, which may affect reproductive outcome adversely.

The aim of the present study was to investigate, whether employment in the Swedish rubber industry from 1973 onwards, i.e. “modern” work conditions, had a negative impact on reproductive health among females as well as among males. The Swedish population registry gives a unique possibility to perform epidemiological studies on reproductive health. Through linkages of a rubber worker cohort to the population registry we identified not only pairs of mothers and child, but also the triads of the legally acknowledged father, mother and child. Outcome data were obtained from the Swedish Medical Birth Register and the Register of Congenital Malformations, which are of good quality, and covers almost all children born in Sweden since 1973 (Otterblad-Olaussen and Pakkanen 2003).

Materials and methods

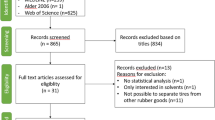

Exposed cohorts

A cohort of rubber manufacture employees has been established, using personnel records from rubber plants, in all 12 production facilities all over Sweden. In all of the facilities, there was production of general rubber goods. One of the facilities also produced tyres. The cohort includes all employees first employed 1965 or later, employed for at least 3 months, in total 12,014 men and 6,504 women. Information on periods of blue-collar employment was available for all subjects. Information on job tasks varied in complexity and completeness between plants, and was not considered to have enough accuracy for use in this study. Statistics Sweden was able to identify all but 1% of the women, and 1% of the men.

Referent cohort

In the year 2001, the Food Worker’s Union provided a list of all female members, 35,757 women from all over the country. Of these, Statistics Sweden was able to identify all but 8 women. All women were blue-collar workers. Information on duration of employment and specific exposures was not available.

Linkage to the Swedish Population Registry to establish cohorts of mothers, fathers and children, and to registers of reproductive outcome

The rubber workers cohort and the female members of the Food Workers Union were linked to the Swedish Population Register by Statistics Sweden. Also, cross-checking with the registries of deaths and births was performed. Thus, the identities of all children born to these women and men between 1973 and 2001 were obtained. Altogether, 17,918 children to rubber workers and 33,487 children to female food industry workers were identified.

In a next step, these children were identified in the Medical Birth Register, which includes almost every infant born in Sweden since 1973. The registry is based on copies of records and forms from the maternity health care, the delivery and the pediatric examination of the newborn. In 1982, several new variables were introduced into the register, for example, information on maternal smoking in early pregnancy. Also, all children were matched to the Register of Congenital malformations, which includes serious congenital malformations reported within 6 months after birth.

In the present study, we restricted the cohort of rubber workers children. The restriction of employment period that was considered for exposure of the child was based on the assumption that there are no accumulated effects of exposure in the rubber industry that affect reproductive outcome. For female workers, only continuous employment as a blue-collar worker during 9 months before the birth of a child was consider as an exposed pregnancy. For male rubber workers, we similarly considered the entire period between 12 and 9 months before the birth of a child as an exposed sperm production period, assuming 3 months for maturation of spermatozoa, and a full term pregnancy. The various combinations of mother’s and father’s rubber work and the number of children in each study group are shown in Table 1. There were altogether 2,828 live-born children with maternal and/or paternal employment during the entire 3 or 9-month period. Children with no parental employment in the rubber industry during these periods constituted the internal reference cohort (n = 12,882). Children with partial parental employment (n = 2,208) during these periods were not included in the present study.

In a second step, we restricted the study to first-child only. In a third step, a restriction within the rubber worker cohort was made including only siblings with contrasting exposure, thus enabling an exposure crossover design. There were 222 children with maternal rubber work during the pregnancy (with or without paternal rubber work), having altogether 255 siblings with neither maternal nor paternal rubber work during the pregnancy and sperm maturation period.

Among food industry workers, 231 children with a father or mother who had ever been a rubber cohort member were excluded. Thus, 33,256 children remained in the study group.

Outcomes measures

The reproductive outcomes studied were offspring sex ratio, birth weight, preterm birth (gestational length ≤ 37 weeks), small for gestational age (SGA) (Källén 1995), large for gestational age (LGA) (Källén 1995), length at birth, head circumference at birth, multiple births, all malformations and stillbirths (week 28 and later). Also, involuntary childlessness for 1 year or more, ever, reported at the pregnancy under study was investigated.

Characteristics of the cohorts

Descriptive maternal data are given in Table 1. The annual number of children with both parents employed in the rubber industry was highest during the 1970s. In contrast, in the food industry workers as well as in the other rubber workers study groups, the annual number of births peaked during the late 1980s and 1990s.

The maternal age distribution was median 26–27 years in the rubber workers study groups, and slightly lower among food industry workers, median 25 years. Accordingly, the proportion of young mothers <20 years was slightly higher among food industry workers. Around 40% of all children were first-born. The maternal height and weight during early pregnancy did not differ between study groups. Information on the maternal native country was available only for births after 1978. Among children with both parents as active rubber workers, a slightly higher proportion of the mothers were immigrants from Europe. In contrast, more food industry workers were non-European. The rubber plants were situated in different parts of Sweden, all of them in provincial towns. The majority in the reference cohort, 79%, resided outside the urban areas of Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö.

Information on maternal smoking during early pregnancy was available from 1983. The proportion of non-smokers among females employed in the rubber industry during the actual pregnancy was 64%, compared to 62% among food industry workers.

Statistical methods

The effect of cohort membership, with the food industry workers’ cohort as a reference category, was investigated using linear regression analysis for continuous outcomes (i.e. birth-weight) and logistic regression analysis for binary outcomes (i.e. multiple births, gender of child, involuntarily childlessness). Mother was incorporated as a random effect in these regression models in order to account for the dependence in outcome within a set of siblings. Only live births were included. As potential confounders, we considered child’s sex, smoking status (non-smoker, smoker), maternal age (−24, 25–29, 30+) and parity (1, 2, 3+) kept together, calendar year of birth (5 year intervals) and maternal ethnicity (Sweden, other Scandinavia, other Europe, non-European). We used the method suggested by Greenland (1989) for deciding which of the potential confounders that should be included in the final multivariate model. Potential covariates were entered into bivariate and multivariate models if they changed the effect estimate by >10%. All regression analyses were conducted using PROC MIXED and PROC NLMIXED in SAS version 8.2. For analyses of first-child only, SPSS was used for the linear and logistic analyses.

In addition, an exposure–crossover design was explored, comparing siblings in rubber worker families with and without maternal exposure during the pregnancy. Linear and logistic analyses were performed without mother as random effect, adjusting only for sex, using SPSS.

Results

The number of stillbirths was similar between groups, varying between 0 and 0.5%. The number of registered malformations was similar between groups, around 4% for all malformations. There was no obvious clustering of specific malformations. Pregnancy outcome for all pregnancies is reported in Table 2 (all live births) and Table 3 (live births, multiple births excluded).

A history of involuntarily childlessness for one year or more, ever (i.e. not only preceding the present pregnancy) was registered from 1983 and on. This was reported in 6.4% of births with any parent ever employed in the rubber industry, compared to 5.5% among food industry workers (Table 1). This corresponds to an odds ration of 1.20 (95% CI 1.09, 1.32) comparing all rubber workers groups (excluding those who were first employed in the rubber industry after the birth of the child) with food workers. When age and parity was included in the model, thus correcting for a potential artificial increase with increasing number of at risk times, the odds ratio was not elevated, OR 0.99 (95% CI 0.90, 1.09).

The sex ratio was reversed, with a loss of boys when the mothers were exposed during the pregnancy (Table 2). The OR for having a girl was 1.15 (95% CI 1.02, 1.31) if only the mother was exposed during the pregnancy. When both parents were exposed, the OR was even higher, 1.28 (95% CI 1.02, 1.62). In the internal reference group (i.e. mother or father was a rubber worker, but not during the observed pregnancy/conception period), the sex ratio was similar to the external reference group. In the exposure–crossover analysis, comparing siblings in rubber worker families and thus reducing the influence of unmeasured confounders, the odds ratio for a girl was 1.44 (95% CI 1.05, 2.07) when the mother was exposed.

When both parents were exposed, an increased proportion of multiple births was observed, 5%, compared to the external reference group (Table 2), corresponding to an OR of 2.42 (95% CI 1.17, 5.01).

The influence of rubber industry employment on birth weight was investigated, excluding multiple births. Girls with both maternal and paternal exposure had a reduced birth weight compared to the external reference cohort, median 3,370 vs 3,440 g (Table 3). Length at birth, and head circumference were similar between groups (Table 3). When mother was incorporated as random effect, the mean weight difference was −101 g (95% CI −189, −13) (Table 4). A lower birth weight was also observed among boys with both maternal and paternal exposure, median 3,455 g vs 3,561 g among external referents (mean difference −106 g, 95% CI −208, −4). When only first-born children were investigated, the effect estimates were very similar, albeit with wider confidence intervals (Table 4). In the exposure–crossover design, comparing siblings in rubber worker families and thus reducing the influence of unmeasured confounders, the estimated effect of maternal rubber work during the pregnancy on birth weight, adjusted for sex, was −53 g (95% CI −153, 48).

Information on smoking and ethnicity was available only for births during the period 1983–2001. After adjustment for these covariates and sex, the weight difference between children with both maternal and paternal exposure and external referents was −142 g (95% CI −229, −54) (Table 4). Neither parity and maternal age kept together nor calendar year of birth changed the effect estimate.

There was a numeric slight increase of preterm births (gestational length <38 weeks) in the group with maternal and paternal exposure (Table 2), corresponding to OR 1.23 (95% CI 0.78, 1.96) vs external referents. When preterm births, which is an intermediary outcome and not a confounder, were introduced in the above-mentioned model in a last step, the estimated birth weight was slightly reduced for children with maternal and paternal exposure, now −91 g (95% CI −170, −12). The estimates for other groups did not change. Thus, preterm births did not explain the observed reduced birth weight, and we are likely to observe intrauterine growth retardation. Also, the risk for growth retardation which fulfilled criteria for “small for gestational age” (Källén 1995) was increased when the mother was exposed during the pregnancy, with OR 2.15 (95% CI 1.45, 3.18; singletons only, adjusting for the sex of the child, maternal age and parity, smoking and ethnicity, and with mother incorporated as random effect). The corresponding ORs in the groups with paternal exposure only, and with no exposure, did not differ significantly from the external referents.

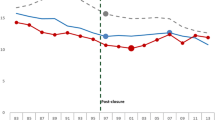

The lower birth weight among both girls and boys was mainly observed during the latter part of the observation period. In a crude analysis, only adjusting for sex, the weight difference between children with both maternal and paternal exposure and the internal reference group for the period 1988–2001 was −164 g (95% CI −260, −68). The corresponding figures for the period 1973–1987 was −21 g (95% CI −113, 71). Similarly, the effect on sex ratio was most marked during the latter period, with OR 1.70 (95% CI 1.23, 2.36) for having a girl, vs OR 0.95 (95% CI 0.69, 1.32) during the early period. Also preterm births were more common in the latter period, OR 2.27 (95% CI 1.27, 4.06) vs 0.50 (95% CI 0.22, 1.13) in the early period.

Discussion

The present analysis gives a crude picture of reproductive outcome among rubber employees, using blue-collar employment in the rubber industry during an assumed full-term pregnancy and/or sperm production and maturation period as the only available proxy for exposure. Such a crude measure of exposure would rather tend to underestimate effects, compared to analyses with a more refined measure of exposure. The strengths of our study are the availability of prospectively collected information on potential confounders for all births, and the use of an external reference cohort of food workers which are likely to have no exposure to chemical agents that have reproductive toxicity, but otherwise being similar with respect to manual work and socioeconomic background. This is of importance, as it has been shown that maternal adulthood class had an impact on birth weight in Sweden during the period that we have studied (Gisselmann 2006), accentuating over time (Gisselmann 2005). The use of an internal referent cohort, and even more the additional exposure–crossover analysis comparing siblings among rubber workers families, further reduced the influence of unmeasured confounders.

We observed several findings, which indicate that there might be adverse effects on reproductive outcome in the rubber industry. The mean birth weight in singletons was reduced by around 100 g if both parents were employed in the rubber industry, similar for boys and girls, and the risk for a SGA child was doubled when the mother was exposed during the pregnancy. This can be compared to the estimated effect of maternal smoking in our study groups, around 200 g. The smoking effect observed was similar to a previous report from Sweden during the 1980s (Ericson et al. 1991).

The perhaps most striking observation was that the offspring sex ratio in female rubber employees was reversed, with fewer boys. It has been hypothesized that mammalian (including human) sex ratios at birth are partially controlled by the hormone levels of both parents at the time of conception (James 2004). Another hypothesis is a more intensive early embryonic selection among males. An altered offspring sex ratio has been observed in populations exposed to persistent organic compounds like PCBs (Karmaus et al. 2002; Mocarelli et al. 2000; Rogan et al. 1999; Rylander et al.1995), and pesticides (Hanke and Jurewicz 2004), albeit not consistently. Also, a reversed sex ratio has been observed after heavy methyl mercury pollution (Sakamot et al. 2001).

The external reference cohort was cross-sectionally defined, in contrast to the rubber workers cohort, which explains the differences in calendar year of births. However, calendar year of birth did not affect the effect estimates, when tested as covariates in multivariate models. It should be noted that all main findings were congruent in the differing comparisons, using external reference cohort, internal reference cohort and within-family comparisons. The proportion of industrial workers being trade union members has traditionally been very high in Sweden. It has been estimated that around 90% of all rubber workers were union members in 2001 (Rosalie Andersson, IF-Metall, personal message). Thus, the differing principles for definitions of the cohorts cannot invalidate our findings.

We had information on employment as a blue-collar rubber worker during the pregnancy and sperm maturation period. Some of the workers may have been absent from work during this period (i.e. sick leave, vacation), but we have no information on such absenteeism. The Swedish social insurance system with generous benefits for sick leave and parental leaves would tend to keep workers with pregnancy-related medical problems to stay employed. Thus, we do not find it likely that there is differential selection out of the work force during pregnancy between rubber workers and food workers that would affect our findings. The analysis of first-child pregnancies rules out differential selection out of the work force when being a mother.

Within the EU Concerted Action “Improved Exposure Assessment for Prospective Cohort Studies and Exposure Control in the Rubber Manufacturing Industry” a job-exposure matrix for exposure to rubber dust and fumes, nitrosamines, and organic solvents, based on more than 46,000 individual occupational hygiene measurements (of which 4,800 from Sweden) has recently been developed (de Vocht et al. 2005). Overall, the levels of inhalable dust seems to have declined by 4% per year since 1975 in compounding, mixing and pre-treatment departments which often are male-dominated in Sweden (de Vocht et al. 2007a, b), but no decline was observed in curing departments during the 1990s. For post-treating departments, where many women are employed, there were no data to allow modeling of exposure trends. A marked decrease in air levels of organic solvents was observed during the 1970s and early 1980s, with continuing decrease, thereafter (ExAs Rub 2004). Recently, extensive occupational hygiene measurements have been performed in the Swedish rubber industry. The surveys were performed mainly in curing areas, and in areas with combined curing and post-processing procedures. High levels of nitrosamines in air were detected in certain curing processes (de Vocht et al. 2007a). Also, elevated urinary levels of phthalates (Vermeulen et al. 2005), and 1-hydroxypyrene as an indicator of PAH-exposure were detected at certain work tasks (Balogh et al. 2003). Measurements from other work areas dominated by female workers, as post-processing procedures, still are scarce. Also, there are few measurements from the male-dominated mixing areas.

Although the substances for which modeling of exposure levels and time trends are available might not be the pertinent ones for reproductive outcome, overall changes in exposure levels due to better workplace hygiene will indeed be reflected. In this perspective, it is intriguing that we observed a stronger effect on birth-weight, offspring sex ratio, and preterm births during the latter part of the observation period in our study, i.e. after 1987. We have at present no good explanation to this finding. Better exposure estimates, not only for chemical exposures but also for other factors that may affect reproductive outcomes, are indeed needed to elucidate this unexpected finding.

From occupational settings outside the rubber industry, there are some indications that paternal solvent exposure is associated with an increased time to pregnancy (Sallmén et al. 1998), and inconsistent findings of low birth weight or preterm birth and spontaneous abortions (Lindbohm 1999). Experimentally, diethylnitrosamine has been shown to be hormonally active (Liao et al. 2001), as well as phthalates (Hoppin et al. 2002). There is evidence from animal data that phthalates have adverse reproductive effects in males (Foeter et al. 2001; Gray et al. 2000; Mylchreest et al. 2002; Nagao et al. 2000), and possibly also females (Ema and Miyawaki 2001). Also, some phthalates have been associated with adverse effects on semen quality in infertile or subfertile couples (Duty et al. 2003; Rozati et al. 2002). Thus, there are several exposure candidates for adverse reproductive outcome within the rubber industry.

Our findings clearly indicate that there is good reason to study reproductive outcome in the rubber industry in more detail. A study on spontaneous abortions and time to pregnancy (Joffe 1997), which assesses the couple’s fertility, is now under way in our cohorts. Male fertility in the rubber industry can be further studied with respect to sperm quality (Bonde et al. 1999; Spanó et al. 1998, 2000). The novel method of assessing the Y:X sperm chromosome ratio with FISH-technique is of special interest (Tiido et al. 2005). Such studies would also benefit from better exposure data, combining information from plant personnel records, subject’s reports, job-exposure matrices, and (for sperm studies) biomarkers of exposure.

References

Axelson O, Edling C, Andersson L (1983) Pregnancy outcome among women in a Swedish rubber plant. Scand J Work Environ Health 9(Suppl 2):79–83

Balogh I, Bergendorf U, Hagmar L et al. (2003) Health risks, prevention and rehabilitation in the rubber industry. Report 2003–03–06 (in Swedish). Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Lund. Available at http://www.ymed.lu.se

Bonde JP, Joffe M, Danscher G, et al (1999) Objectives, designs and populations of the European Asclepios study on occupational hazards to male reproductive capability. Scand J Work Environ Health 25(Suppl 1):49–61; discussion 76–8

de Celis R, Feria-Velasco A, Gonzalez-Unzaga M (2000) Semen quality of workers occupationally exposed to hydrocarbons. Fertil Steril 73(2):221–8

Duty SM, Silva MJ, Barr DB, et al (2003) Phtalate exposure and human semen parameters. Epidemiology 14:269–77

Ema M, Miyawaki E (2001) Effects of monobutyl phthalate on reproductive function in pregnant and pseudopregnant rats. Reprod Toxicol 15:261–7

Ericson A, Gunnarskog J, Källén B, et al (1991) Surveillance of smoking during pregnancy in Sweden, 1983–1987. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 70:111–7

ExAsRub (Exposure assessment in the rubber industry) (2004) Improved exposure assessment for prospective cohort studies and exposure control in the rubber manufacturing industry. In: Hans Kromhout (ed). Final report from the ExAsRub consortium, EU concerted action, QLK4-CT-2001-00160 and QLK4-CT-2002-02786. Utrecht, The Netherlands

Figa-Talamanca I (1984) Spontaneous abortions among female industry workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Med 54:163–71

Foster PM, Mylchreest E, Gaido KW, et al (2001) Effects of phthalate esters on the developing reproductive tract of male rats. Hum Reprod Update 7(3):231–5

Gisselmann M (2005) Education, infant mortality, and low birth weight in Sweden 1973–1990: Emergence of the low birth weight paradox. Scand J Public Health 33:65–71

Gisselmann M (2006) The influence of maternal childhood and adulthood social class on the health of the infant. Soc Sci Med 63:123–33

Gray LE Jr, Ostby J, Furr J, et al (2000) Perinatal exposure to the phthalates DEHP, BBP, and DINP, but not DEP, DMP, or DOTP, alters sexual differentiation of the male rat. Toxicol Sci 58(2):350–65

Greenland S (1989) Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am J Public Health 79:340–9

Hanke W, Jurewicz J (2004) The risk of adverse reproductive and developmental disorders due to occupational pesticide exposure: an overview of current epidemiological evidence. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 17:223–43

Hoppin JA, Brock JW, Davis BJ, et al (2002) Reproducibility of urinary phthalate metabolites in first morning urine samples. Environ Health Perspect 110(5):515–8

James WH (2004) Further evidence that mammalian sex ratios at birth are partially controlled by parental hormone levels at the time of conception. Hum Reprod 19(6):1250–6

Joffe M (1997) Time to pregnancy: a measure of reproductive function in either sex. Asclepios Project. Occup Environ Med 54(5):289–95

Källén B (1995) A birth weight for gestational age standard based on data in the Swedish medical birth registry, 1985–1989. Eur J Epidemiol 11:610–6

Karmaus W, Huang S, Cameron L (2002) Parental concentration of dichlorodiphenyl dichloroethene and polychlorinated biphenyls in Michigan fish eaters and sex ratio in offspring. J Occup Environ Med 44:8–13

Kogevinas M, Sala M, Boffetta P, et al (1998) Cancer risk in the rubber industry: a review of the recent epidemiological evidence. Occup Environ Med 55(1):1–12

Liao DJ, Blanck A, Eneroth P, et al (2001) Diethylnitrosamine causes pituitary damage, disturbs hormone levels, and reduces sexual dimorphism of certain liver functions in the rat. Environ Health Perspect 109(9):943–7

Lindbohm ML (1999) Effects of occupational solvent exposure on fertility. Scand J Work Environ Health 25(Suppl 1):44–6

Lindbohm ML, Hemminki K, Bonhomme MG, et al (1991) Effects of paternal occupational exposure on spontaneous abortions. Am J Public Health 81(8):1029–33

McDonald AD, McDonald JC, Armstrong B, et al (1988) Congenital defects and work in pregnancy. Br J Ind Med 45(9):581–8

Mocarelli P, Gerthoux PM, Ferrari E, et al (2000) Paternal concentrations of dioxin and sex ratio of offspring. Lancet 355:1858–63

Mylchreest E, Sar M, Wallace DG, et al (2002) Fetal testosterone insufficiency and abnormal proliferation of Leydig cells and gonocytes in rats exposed to di(n-butyl) phthalate. Reprod Toxicol 16(1):19–28

Nagao T, Ohta R, Marumo H, et al (2000) Effect of butyl benzyl phthalate in Sprague-Dawley rats after gavage administration: a two-generation reproductive study. Reprod Toxicol 14(6):513–32

Otterblad-Olaussen P, Pakkanen M (2003) The Swedish Medical Birth Register. A summary of content and quality. Center for Epidemiology, The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, Stockholm (article nr 2003-112-3) http://www.sos.se

Rendon A, Rojas A, Fernandez SI, et al (1994) Increases in chromosome aberrations and in abnormal sperm morphology in rubber factory workers. Mutat Res 323(4):151–7

Rogan WJ, Gladen BC, Guo YL, et al (1999) Sex ratio after exposure to dioxin-like chemicals in Taiwan. Lancet 353:206–7

Rozati R, Reddy PP, Redanna P, et al (2002) Role of environmental estrogens in the deterioration of male fertility. Fertil Steril 78:1187–1194

Rylander L, Srömberg U, Hagmar L (1995) Decreased birthweight among infants born to women with a high dietary intake of fish contamined with persistent organochlorine compounds. Scand J Work Environ Health 21:368–75

Sakamoto M, Nakano A, Akagi H (2001) Declining Minamata male birth ratio associated with increased male fetal death due to heavy methyl mercury pollution. Environ Res 87:92–8

Sallmén M, Lindbohm ML, Anttila A, et al (1998) Time to pregnancy among the wives of men exposed to organic solvents. Occup Environ Med 55:24–30

Savitz DA, Whelan EA, Kleckner RC (1989) Effects of parents´ occupational exposures on risk of stillbirths, preterm delivery, and small-for-gestational-age infants. Am J Epidemiol 29:1201–18

Spanó M, Kolstad AH, Larsen SB, et al (1998) The applicability of the flow cytometric sperm chromatin structure assay in epidemiological studies. Asclepios. Hum Reprod 13(9):2495–505

Spanó M, Bonde JP, Hjollund HI, et al (2000) Sperm chromatin damage impairs human fertility. The Danish First Pregnancy Planner Study Team. Fertil Steril 73(1):43–50

Tiido T, Rignell Hydbom A, Jönsson BAG, et al (2005) Serum levels of p,p'-DDE and CB-153 in relation to human sperm Y:X chromosome ratio. Hum Reprod 20(7):1903–9

Vermeulen R, Jönsson BAG, Lindh CH, et al (2005) Biological monitoring of carbon disulphide and phthalate exposure in the contemporary rubber industry. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 78(8):663–9

de Vocht F, Straif K, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, et al, on behalf of the EXASRUB consortium (2005) A database of exposures in the rubber manufacturing industry; Design and quality control. Ann Occ Hyg 49(8):691–701

de Vocht F, Burstyn I, Straif K, et al (2007a) Occupational exposure to NDMA and NMor in the European rubber industry. J Environ Monit 9:253–9

de Vocht F, Vermeulen R, Burstyn I, et al (2007b) Exposure to inhalable dust and its cyclohexane soluble fraction since 1970 in the rubber manufacturing industry in the European Union. Occup Environ Med, on-line publication Oct 10. doi:10.1136/oem.2007.034470

Acknowledgments

In memoriam of Professor Lars Hagmar, who took part in the planning of the study and the writing of the first version of the manuscript. Jonas Björk and Håkan Lövkvist gave valuable assistance with the statistical modeling. We gratefully acknowledge the cooperation from the rubber plant personnel, and local trade union representatives, and from a reference group with representatives from the employers and The Industrial Workers’ Union. The Swedish Food Workers Union kindly provided member lists. This study was financially supported by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (FAS) and the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Sweden. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing financial interests.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author’s contribution

Kristina Jakobsson was the main author of the manuscript. Zoli Mikoczy supervised the cohort assembly, handled the registry data, performed the data analysis, and participated in the writing of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jakobsson, K., Mikoczy, Z. Reproductive outcome in a cohort of male and female rubber workers: a registry study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 82, 165–174 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-008-0318-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-008-0318-0