Abstract

The paper is inspired by recent experiment with a two-member discrete column subjected to dry friction force of interaction between the moving column and a moving plane. The experiment was presented in the form of a YouTube film and recommended as an experimental evidence for flutter in the Ziegler column. We show that the tested mechanism cannot be identified with the original Ziegler column.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The history of studies on stability of columns subjected to compressive forces goes back to Euler who analyzed the static buckling of elastic compressed rods and formulated the theory of buckling even now being used in the courses of strength of materials as a first attempt to address the stability problems of light load-carrying structures [1]. The problem was refreshed and attracted much attention of scientists in structural mechanics in the second half of the last century when flutter was theoretically found as a result of so-called follower forces that change their direction, following the current configuration of a system they act on (Bolotin [2]). Earlier, Ziegler [3] found flutter instability in a discrete two-degree-of-freedom double-rod system, now well-known as the Ziegler column.

The dynamical behavior of systems under assumed compressive follower forces showing flutter (like classical Beck and Leipholz columns) is not questionable and there are numerous studies of such systems demonstrating their specific properties, optimization and control. However, still rather little is known about the physics behind pure follower forces and there is skepticism among some scientists about the technical sense of the follower forces. Koiter denied the importance of such forces even knowing the results by Sugiyama concerning the effect of rocket propulsion as a source of a follower load acting on a beam [4]. Their contradicting opinions on the subject were expressed in the two publications in the Journal of Sound and Vibration:

-

Koiter W.T., 1996: Unrealistic follower forces [5],

-

Sugiyama Y., Langthjem M.A., Ryu B.J., 1999: Realistic follower forces [6].

An impressive overview of rich literature on mechanical systems under follower forces was given by Elishakoff [7] who was inspired by the discussion between Koiter and Sugiyama on the physical sense of what was called “follower forces” in the literature. First he wrote “Essay on the so-called follower forces” (after Koiter’s death in 1997), addressing it as a private publication to a group of scientists for their opinions (Besseling, Bogacz, Bolotin, Dimitriyk, Doak, Herrmann, Karihaloo, Kounadis, Maier, Nemet-Nasser, Padoussis, Panovko, Seyranian and Sugiyama).

Publication by Elishakoff [7] caused more interest of scientists in theoretical and experimental studies of mechanisms subjected to follower forces of various physical nature and technical importance [8]. The most important reference to the present paper is the experiment by Bigoni and Noselli [9] presented also in the form of a YouTube film and recommended as an evidence for flutter in the Ziegler column. In the following, we show the differences between the tested real mechanism and the Ziegler column in its original concept and formulation.

2 Models of the Ziegler column and the mechanism being tested in[9]

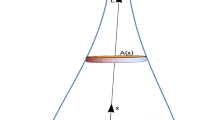

The original Ziegler column consists of two rigid rods linked and supported with joints and rotary springs, as shown in Fig. 1a. The compressive follower force applied to the free end of the column is assumed to be constant in magnitude and directed along the rod. All possible forces and moments of resistance (damping) are neglected. The original Ziegler column has two degrees of freedom.

Consider a Ziegler column in the version examined by Bigoni and Noselli [9] in their calculations. It is sort of a simplified system in which the rigid elements of the column, i.e. the arms, have been replaced with massless rods and particles m attached to the middles of each of them, see Fig. 1b. In further simplification, it has been assumed that lengths of the weightless rods are the same (l), both particle masses and torsional stiffnesses of the joints the same too. The follower force F remains a purely tip-concentrated circulatory load. Since we face with particles instead of lengthy beams, the derivation of kinetic energy of the whole system becomes exceptionally easy and hence the making use of Lagrange’s formalism quickly brings the final form of the equations of motion which are given below:

By linearizing, one arrives at:

or in a matrix form:

where the vector \({\varvec{\Phi }}\)is \({\varvec{\Phi }}=[\varphi _{1} , \varphi _{2}]\). Predicting the exponential solution in the form \({\varvec{\Phi }}={\varvec{\Omega }}\exp \{rt\}\), substituting it into (3) and demanding the determinant of the thus generated system of homogeneous algebraic equations to be zero for the existence of non-trivial solution, one gets a characteristic equation in the eigenvalue r:

Introducing new parameters:

one rewrites (4) in the following form:

the solution in which are two pairs of complex conjugate roots:

Analysis of behavior of the obtained eigenvalues in the complex plane is shown in Fig. 2.

Trajectories of the eigenvalues of the Ziegler column analyzed in [9]

If the system is free from the follower load (\(q=0)\), it remains stable—one observes four dots in Fig. 2, all lying in the imaginary axis. A nonzero and growing q make the dots (eigenvalues) travel along the ordinates and come in pairs closer to each other. Until they eventually meet, the system is still stable. Things get qualitatively changed when the eigenvalues merge and create only two pairs, which happens at \(q=3\). This is some criticality above which (\(q>3)\) the characteristic roots move clockwise along a circle—one eigenvalue with a negative real part, the other with positive, both with nonzero imaginary parts. This situation is the onset of dynamic instability known in mechanics as flutter—self-excited vibration of a certain amplitude established by nonlinearity embedded in the system. Exceeding \(q=13/3\), one finds out that both roots reach abscissa with nonzero real parts what obviously entails another type of instability-divergence. Zeroed all imaginary parts (\(Im\{r\}=0)\) and only a single positive real part of any root (\(Re\{r\}=0)\) are the evidence of no vibration and inevitable drift of the initial equilibrium to infinity. All the above-described behavior of the eigenvalues can also be shown in a bit different manner, see Fig. 3, where the real and imaginary parts are separately displayed and expressed as a function of magnitude of the applied load q.

Real (a) and imaginary (b) parts of the eigenvalues (7) vs follower load q

The experiment by Bigoni and Noselli is exactly an interesting proposal and method to test the theory. The authors and designers [9] conceived a tricky idea of making a mechanical system non-conservative and follower loaded. They added a perpendicularly oriented roller to the tip of the second arm of the Ziegler column and harnessed dry friction to do the final job. The friction is generated between the roller and a rough band moving steadily with constant velocity V beneath the roller. The friction force comes from slipping in the point of contact of the roller and the translating band. Neglecting inertia of the roller as well as rolling resistance, such a structural solution may indeed produce a concentrated load that follows the direction (\(\varphi _2 )\) of the second element of the Ziegler column.

The main intention of this paper is to investigate the problem of inertia of the roller and its effect on the dynamics of the entire system, now being a three-degrees-of-freedom one. The regions of stability and the extent of how they might be affected by the additional DOF are of special interest in the subsequent considerations. Admittedly, some discussion on that topic has been already taken up by Bigoni et al. [10].

3 Ziegler column with a roller

Analyze now the system depicted in Fig. 1c. In order to incorporate Lagrange’s equations of the second kind and to derive dynamical equations of motion, we require to determine kinetic and potential energy first. Assume for this purpose that the generalized coordinates of the considered three-degrees-of-freedom system are angles of rotation of the arms \(\varphi _2 \) and \(\varphi _2 \), both measured relative to the axis x and rotation of the roller denoted by \(\psi \). According to König’s theorem, the kinetic energy is:

where \(m_i \) is mass of the i-th element, \(v_{Ci} \)–velocity of its center of gravity, \(I_{C1} \) and \(I_{C2} \) moments of inertia of the arms with respect to the central axes \(z_{C1} \) and \(z_{C1} \), respectively, \({\varvec{\omega }}_3 \)—vector of the rotation velocity of the roller, \(\mathbf{I}_3 \)—tensor of inertia expressed in the principal coordinate system of the roller. The following hold:

Now let us determine kinetic energy of the roller. The vector of rotation speed is shown in Fig. 4.

The roller rotates with respect to its own axis (directed along the second arm) with spin velocity \(\omega _\psi =\dot{\psi }\). At the same time, it performs rotation with respect to the z axis together with the second arm of the column \(\omega _z =\omega _2 =\dot{\varphi }_2 \). To clarify the description, introduce now a coordinate system fixed to the roller and based on its principal axes of inertia \(Bn\tau z\), see Fig. 4. In that case:

and the tensor of inertia in \(Bn\tau z\):

so the kinetic energy related to rotation of the roller only will be:

Carrying out all necessary differentiations and simplifications, one arrives at the following form of the entire kinetic energy:

The potential energy comes only from springs mounted in the articulated joints, i.e. in points Oand A. These are linear springs, and thus their energy is:

No sources of energy dissipation are taken into account in our considerations. At this moment, the right-hand sides of Lagrange’s equations should be determined. In the system analyzed, the non-potential load is brought about by dry friction generated between the roller and moving band. As we know, the vector of Coulomb friction is exactly opposite to the direction of relative velocity in the point of rubbing contact:

where \(\mu \) denotes the coefficient of dry friction, R is the normal force in the contact point, \(\mathbf{w}\)—vector of relative velocity of the bottom point of the roller with respect to the moving band, w—magnitude of this velocity \(w=|\mathbf{w}|\). Neglecting any gyroscopic effect due to spatial motion of the roller, it is allowable to assume that \(R=\hbox {const}\). The relative velocity is the difference between the absolutely velocity of the bottom point (K) of the roller which is in contact with the moving bang slipping beneath the roller and the absolute velocity of the band V, see Fig. 5.

The absolute velocity of the bottom point K of the roller is:

where

If so, then:

and according to what has been already stated, see (16)

The vector of relative velocity and, consequently, the vector of the friction force are shown in Fig. 6. As can be noticed, generally, the friction load vector may not always (if ever) coincide with the direction of the second arm of the Ziegler column.

The friction force may deviate from the normal (follower) direction by an angle \(\delta \) (variable in time, predictably) whose value can be found from the following reasoning. In Fig. 6, one can see that:

Substituting the corresponding components from (21), after some manipulations, one obtains:

As far as the magnitude of the friction force is concerned, it stays constant (the proof is obvious).

It is now possible to derive the right-hand sides of the equations of motion. By definition, generalized forces can be found from the following expression:

where \(j=1, 2, 3\) and correspond to all degrees of freedom: \(q_1 =\varphi _1 , q_2 =\varphi _2 , q_3 =\psi \), n is the number of real forces (\(n=1\) in the problem considered, the friction force only), \(\mathbf{r}_i \) are position vectors of the real forces (there is only one such vector \(\mathbf{r}_1 =\mathbf{r}_K )\). Thus:

where

and where the relative velocity amounts to:

Substituting (26) into (25) and differentiating, one gets:

4 Stability of the system

The three governing equations of system dynamics implicitly are written in Lagrange’s formalism:

where, again, \(q_1 =\varphi _1 , q_2 =\varphi _2 , q_3 =\psi \) lead to the following set of nonlinear equations of motion

Before examining stability of the above system, it must be linearized around the equilibrium position first (trivial equilibrium in this problem). Additionally, assuming for simplicity that \(m_1 =m_2 =m\), \(l_1 =l_2 =l\), \(k_1 =k_2 =k\), see Fig. 7, one obtains:

where \(L_1 \) and \(L_2 \) are linear terms of \(Q_1 \) and \(Q_2 \). Naturally, \(L_i =L_i (\varphi _1 ,\varphi _2 ,\psi ,\dot{\varphi }_1 ,\dot{\varphi }_2 ,\dot{\psi })=L_i ({\varvec{\Phi }},{\dot{\varvec{\Phi }}})\) and \(Q_i =Q_i (\varphi _1 ,\varphi _2 ,\psi ,\dot{\varphi }_1 ,\dot{\varphi }_2 ,\dot{\psi })=Q_i ({\varvec{\Phi }},{ \dot{\varvec{\Phi }}})\). If so, then \((i=1 , 2)\):

Explicitly, the linear forms of the generalized forces are:

Now let us rewrite (31) while introducing some new parameters first:

Dividing all both sides of (31) by \(ml^{2}\), we obtain:

The right-hand sides will be then:

By denoting \(k/ml^{2}=a\) and \(R l/k=q\), we have:

Putting it all together, one gets:

or in a matrix form:

which, in turn, can be briefly presented as:

and where the matrices \(\mathbf{I}, \mathbf{G}, \mathbf{Q}\) correspond to those in (39). By predicting a general solution to (40) in an exponential form \({\varvec{\Phi }}={\varvec{\Omega }} \exp \{\lambda t\}\), where \({\varvec{\Omega }} \) denotes eigenvectors and \(\lambda \) eigenvalues to be found, one arrives at the characteristic equation of the sixth order in \(\lambda \):

The above algebraic equation yields three pairs of complex conjugate roots in general. Their values have been determined through numerical simulation carried out for various parameters of \(\nu , \rho , \mu , a, l, V\) and a growing load q. Exemplary results are shown in Fig. 8 for \(\nu =\rho = \mu =0.1, l=1 \hbox {m}, V=0.1 \hbox {m/s, } a=0.1 1/s^{\hbox {2}}\)and the force increasing quasi-statically and starting from zero. The results take into account the effect of inertia of the roller and its influence on the direction of the friction force which remains no longer purely follower, see (22). A diagram showing real and imaginary parts of the obtained eigenvalues is given in Fig. 8. Black lines are the eigenvalues of the classical Ziegler problem for a two-degrees-of-freedom column, and the gray lines depict the analyzed 3-DOF system, i.e. the column with the roller and friction force deviating from the follower direction. As can be seen, the system is degenerate (one pair of eigenvalues is zero—the gray horizontal line in both diagrams coinciding with the abscissa). This is because of the third column in the matrix \(\mathbf{Q}\), which contains zeros only, see (39) and (40), and which, physically, means that the roller may rotate without any elastic restriction (infinitely).

Nevertheless, both results, that are purely academic (black curves) and theoretical but including some aspects of Bigoni’s experiment (gray ones), are in qualitative agreement. Theoretical considerations of the modified (3-DOF) Ziegler-like column confirm the existence of the experimentally proved in [9] regions: stability, flutter and divergence versus growing load q. Some quantitative differences between both findings mainly concern the onset of flutter which appears for q below 3 in the column equipped with the roller. And that is in agreement with the conclusion drawn by Bigoni et al. in their contribution [10].

5 Concluding remarks

The experimental effort made by Bigoni and Noselli with coworkers on a mechanism exhibiting flutter and divergence instabilities induced by dry friction is impressive. The authors proved that dry friction may cause flutter like the follower force does in the exclusively theoretical Ziegler column. The smart technical solution proposed by the investigators is an inventive concept. However, the mechanism being tested is not strictly the Ziegler column. It is a Ziegler-like structure only.

The intention of the present paper was to indicate that in practical conditions the analyzed system loses its academic purity and becomes a three-degrees-of-freedom system instead of a 2-DOF one like in the classical formulation. The generated friction force is not exactly follower as it generally has a transverse component, caused by the inertia of the roller. In consequence, the follower force is not constant in magnitude but depends on the configuration and velocities. The mechanism becomes the Ziegler column if the roller is massless.

Nonetheless, the final results occurred to be in full qualitative agreement with the outcomes presented in [9] and [10]. The examined system behaves like Ziegler’s—it has regions of stable operation, self-excited vibration and divergent instability. It should be emphasized that the model excludes by assumption the stick-slip phenomena often encountered in systems with dry friction. In other words, velocity of the moving band should be high enough to eliminate the stick-slip effect. Moreover, the model shows singularity in the neighborhood of equilibrium when the band velocity tends to zero. It results from the discontinuous characteristic of Coulomb dry friction. The problem remains open, and further research work is expected.

References

Euler, L.: Determinatio onerum, quae columnae gestare valent. Acta Acad. Sci. Petropolitanae 1, 121–145 (1778)

Bolotin, V.V.: Nonconservative Problems in the Theory of Elastic Stability. Pergamon, New York (1964)

Ziegler, H.: Die Stabilitätskriterien der Elastomechanik. Ingenieria 20, 49–56 (1952)

Sugiyama, Y., Katayama, K., Kinoi, S.: Flutter of cantilever column under rocket thrust. J. Aerosp. Eng. 8, 9–15 (1995)

Koiter, W.T.: Unrealistic follower forces. J. Sound Vib. 194, 636–638 (1996)

Sugiyama, Y., Langthjem, M.A., Ryu, B.J.: Realistic follower forces. J. Sound Vib. 225, 779–782 (1999)

Elishakoff, I.: Controversy associated with the so-called “follower forces”: critical overview. Appl. Mech. Rev. 58, 117–142 (2005)

Kurnik, W., Bogacz, R.: Ziegler problem revisited—flutter and divergence interactions in a generalized system. Mach. Dyn. Res. 37, 71–84 (2013)

Bigoni, D., Noselli, G.: Experimental evidence of flutter and divergence instabilities induced by dry friction. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 59, 2208–2226 (2011)

Bigoni, D., Misseroni, D., Noselli, G., Zaccaria, D.: Surprising instabilities of simple elastic structures. In: Kirillov, O.N., Pelinovsky, D.E. (eds.) Nonlinear Physical Systems. Wiley, Hoboken (2013)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kurnik, W., Przybyłowicz, P.M. & Bogacz, R. Bigoni and Noselli experiment: Is it evidence for flutter in the Ziegler column?. Arch Appl Mech 88, 203–213 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00419-017-1294-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00419-017-1294-1