Abstract

Objective

Data on post-stroke use of antidepressants in young individuals are scarce. We examined pattern and factors associated with initiating post-stroke antidepressants (PSAD) after ischemic stroke (IS) in young adults.

Methods

Helsinki Young Stroke Registry includes patients aged 15–49 years with first-ever IS, 1994–2007. Data on prescriptions, hospitalizations and death came from nationwide registers. We defined time of initiating PSAD as time of the first filled prescription for antidepressants within 1 year from IS. We assessed factors associated with initiating PSAD with multivariable Cox regression models, allowing for time-varying effects when appropriate.

Results

We followed 888 patients, of which 206 (23.2%) initiated PSAD. Higher hazard of starting PSAD within the first 100 days appeared among patients with mild versus no limb paresis 2.53 (95% confidence interval 1.48–4.31) and during later follow-up among those with silent infarcts (2.04; 1.27–3.28), prior use of antidepressants (2.09; 1.26–3.46) and moderate versus mild stroke (2.06; 1.18–3.58). The relative difference in the hazard rate for moderate–severe limb paresis persisted both within the first 100 days (3.84, 2.12–6.97) and during later follow-up (4.54; 2.51–8.23). The hazard rate was higher throughout the follow-up among smokers (1.48; 1.11–1.97) as well as lower (1.78; 1.25–2.54) and upper white-collar workers (2.00; 1.24–3.23) compared to blue-collar workers.

Conclusion

One-fourth of young adults started PSADs within 1 year from IS. We identified several specific clinical characteristics associated with PSAD initiation, highlighting their utility in assessing the risk of post-stroke depression during follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression after stroke affects nearly a third of all patients, affecting the quality of life of the patient and worsening the outcome [1,2,3,4,5,6]. This appears to apply also to young individuals [7], thus remarkably affecting their general health, vocational performance, and family relations.

Most patients develop symptoms of depression shortly after the acute event [2, 6]. Disability and pre-stroke depression are the most consistently reported predictors of post-stroke depression in older patients, in addition to cognitive impairment, stroke severity, lack of social or family support, and anxiety [2, 6]. Similar factors are found to be associated with post-stroke depression in young stroke patients as well [8], although the evidence is scarce [8]. Post-stroke depression itself is associated with lower quality of life and reductions in activities of daily living, impaired functional recovery as well as increased disability and mortality [2, 6, 9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Depression after stroke is associated with long-term mortality also in younger individuals [16] and even solely using antidepressants after stroke is suggested to increase mortality or lead to other unfavorable outcomes [9, 17, 18]. Moreover, stroke patients are treated with antidepressants more often than patients with other chronic conditions [19] while increasing stroke severity is shown to be associated with higher likelihood of newly prescribed antidepressant medication [20].

However, prevalence and factors associated with newly initiated post-stroke antidepressants (PSADs) are poorly known in the young. Thus, we aimed to characterize the initiation of antidepressants after ischemic stroke (IS) in young adults.

Methods

Study population

In this registry-based follow-up study, we studied patients with first-ever IS that occurred at the age of 15–49 years between January 1994 and May 2007. Our cohort originates from the Helsinki Young Stroke Registry (HYSR), consisting of 1008 consecutive young patients with first-ever IS treated in the Department of Neurology, Helsinki University Hospital, as identified from a prospective computerized hospital discharge database. We utilized the original WHO stroke definition, however also including those with imaging-positive findings of IS despite a short symptom duration [21]. We further combined HYSR data with the data from several national registries using personal identification number, which is assigned to every resident in Finland. From the present study, we excluded patients who had a false primary diagnosis, could not be linked to databases, died within 3 weeks from IS (early i.e., in-hospital deaths), or had antidepressant use within 1 year prior to index stroke (cannot be classified as initiating PSAD use during the follow-up).

Baseline data

Baseline laboratory and other diagnostic tests have been previously fully described [22]. Brain imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed for all patients. We collected patients’ sociodemographic data, i.e., age, sex, socioeconomic status [23], prior antidepressant use, prior psychiatric hospitalization; data on risk factors for IS, i.e., cigarette smoking status at the time of index IS, heavy alcohol use (consumption over 200 g a week), history of drug abuse, cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus type 1 and 2; and data on stroke-related variables measured at admission, i.e., NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS), Trial of Org 10,172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification, infarct size and laterality, silent infarcts, and leukoaraiosis [22].

Information on hospitalizations from any psychiatric reasons, including mood disorders, psychotic disorders, and other psychiatric reasons (International Classification of Diseases, eighth revision (ICD-8) categories 291–299, 300–301, ninth revision (ICD-9) categories 295–298, 300–301, 309, and tenth revision (ICD-10) categories F04–F09, F20–F48, F60–69) ever prior to IS was obtained from the Care Register for Health Care, maintained by the National Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland, from 1969 to the end of 2011. Socioeconomic status was classified according to the patient’s occupation as upper white-collar worker, lower white-collar worker, blue-collar worker, and other (entrepreneur, student, pensioner, and unemployed) or unknown [23]. Based on NIHSS score at admission, stroke severity was categorized as mild (NIHSS 0–6), moderate (NIHSS 7–14) and severe (NIHSS ≥ 15).

Initiation of antidepressants

We obtained data on filled prescriptions (i.e., purchases) from 1993 to the end of 2011, including date of purchase and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes (WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, 2018), from the Drug Prescription Register kept by the Social Insurance Institution of Finland. The Drug Prescription Register includes information on all prescriptions assigned by any physician in Finland. In Finland, prescribed medications are entitled to reimbursement scheme (reimbursement of 40–100% of the medicine’s price) and the Social Insurance Institution of Finland can only reimburse a quantity of medication equivalent to 3 months of treatment at any one time, thus the typical interval of the purchases are 3 months. Based on ATC code N06A, we identified those who purchased antidepressants before and after the index IS. In this study, we defined PSAD initiators to be those patients who had at least one purchased antidepressant medication prescription during the first year after the index IS. We considered patients with filled prescription earlier than 1 year prior to index IS as prior antidepressant users. The follow-up started at the index stroke and ended at the first PSAD purchase, death, or at 1 year from IS, whichever came first.

Statistical analyses

The baseline characteristics of the patients are presented with descriptive statistics for all IS patients and stratified by initiation of PSAD. We reported median and interquartile range for continuous variables and number of observations and percentages for categorical variables. The missingness of data was reported as number of observations and percentages. We demonstrated the numbers of different types of antidepressants used by Venn diagram.

Univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazard’s regression models were fitted to the data on the entire study population to analyze the hazard of initiating antidepressants within the first year after index IS with regard to the baseline characteristics. Based on the univariate Cox regression model, we identified variables with p value < 0.10 to be further studied in the multivariable analysis. In multivariable analysis, we considered age and sex as essential to control for and forced them into the model. The final model was constructed using backward stepwise selection with cut-off of p < 0.05 for variables to be included. There was no considerable collinearity (variance inflation factors > 5) between covariates included into the final model. We checked whether proportional hazards assumption held for the variables included into the final Cox regression model. In case of non-proportional hazards, we allowed for time-varying coefficients. From these analyses, we reported crude and adjusted as well as time-varying hazard ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the initiation of antidepressants. In addition, we modeled and plotted the hazard rate of initiating PSAD as a function of follow-up time using the restricted cubic spline function. The cumulative incidence curves assessing differences in survival with log-rank test were used to visualize the overall and stratum-specific initiating of PSAD. We did additional analysis by also including patients with antidepressant use within 1 year prior to IS to see whether the main results would change. We used Kaplan–Meier curves to examine the survival probabilities for patients using antidepressants at different time points before the index event.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 25.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and with the R software (R Core Team, 2020) [24].

Results

Initiation of antidepressants after stroke

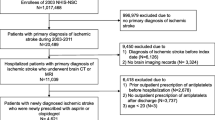

After applying exclusion criteria, a total of 888 patients were followed up (Fig. 1), of which 206 (23.2%) initiated PSAD in the first year after index IS. During the first year from IS, 14 (1.6%) patients without purchase of antidepressants and 3 (0.3%) patients with PSAD died. A total of 73 (8.2%) patients and 31 (15.0%) of the PSAD initiators had used antidepressants at some point earlier than 1 year preceding the index IS.

Of the 206 patients initiating PSAD, 33 (16.0%) used non-selective monoamine reuptake inhibitors, 187 (90.8%) used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and 82 (39.8%) used some other antidepressant, with considerable overlap and use of different antidepressants over time (Fig. 2).

Median time to first PSAD purchase was 102 days (interquartile range 50–163) and the hazard rate of initiating PSAD was highest during the first 100 days since IS (Fig. 3). A total of 101 (49.0%) of the PSAD initiators started use within 100 days and 105 (51.0%) after 100 days from IS. The only statistically significant difference in clinical characteristics between the early and late PSAD starters was the more frequent history of psychiatric hospitalizations among late starters (data not shown). A total of 116 (56.3%) PSAD initiators had their second purchase within 3 months and 159 (77.2%) within 6 months from the first filled prescription. Eleven (11.7%) of patients under 30 years old, 47 (25.0%) of patients aged 30–39 years and 148 (24.4%) of patients over 40 years started PSAD. However, age was not statistically significant factor in the multivariable models.

Table 1 depicts the baseline characteristics of PSAD non-initiators and initiators (Supplementary Material 1 presents the numbers for these groups combined). Compared to patients without starting PSAD, PSAD starters were less often blue-collar workers, more often cigarette smokers, they had more often moderate and severe strokes and silent infarcts, as well as large anterior infarcts and infarcts caused by large-artery atherosclerosis. At the time of hospital discharge, PSAD starters had more often limb paresis and aphasia. These patients also had more often history of psychiatric hospitalization and antidepressant use.

In the univariate Cox regression analysis, several factors, including sociodemographic factors, risk factors for IS and clinical IS data, were associated with initiating PSAD (Table 2).

The final multivariable model (n = 863, 2.8% excluded due to missing value in socioeconomic status and limb paresis at discharge) included age, sex, socioeconomic status, antidepressant use (earlier than 1 year) prior to stroke, current cigarette smoking at the time of index IS, NIHSS score at admission, limb paresis at discharge, and silent infarcts (Table 2). Cumulative incidence curves of initiating PSAD and numbers of patients at risk for all patients and for variables included to the final model are shown in Supplementary Material 2.

The proportional hazards assumption was violated for prior use of antidepressants, silent infarcts, stroke severity, and limb paresis at discharge. To account for non-proportionality, we split the follow-up time into two time strata (PSAD started ≤ 100 or > 100 days) and fitted the Cox regression model when allowing for time-varying coefficients (Table 3). Based on this model, moderate stroke symptoms on admission, limb paresis at discharge, higher socioeconomic status, prior use of antidepressants, silent infarcts, and current smoking were associated with a higher hazard rate of initiating PSAD. In addition, the model showed that prior use of antidepressants, moderate stroke symptoms at admission as well as silent infarcts, were only associated with PSAD initiated after 100 days. Moreover, mild limb paresis at discharge was only associated with PSAD initiated within the first 100 days and the relative difference in the hazard rate for moderate–severe limb paresis compared to no paresis persisted both within the first 100 days and during later follow-up.

If also including patients with recent antidepressant use (n = 78) in the study population, higher socioeconomic status, antidepressant use before IS, silent infarcts, current smoking, and moderate to severe limb paresis at discharge were associated with increased hazard for starting PSAD. Mild limb paresis at discharge was associated with PSAD initiated within the first 100 days from IS, whereas moderate as well as severe stroke symptoms at admission were associated with PSAD initiated after 100 days (data not shown). In visual comparison, the cumulative survival probabilities were substantially different in patients with recent antidepressant use prior IS compared to those with earlier or no use prior IS (Supplementary Material 3). Furthermore, when combined on our analyses and adjusted also for other factors, antidepressant use within 1 year prior IS increased the hazard of starting PSAD (data not shown), suggesting these patients being those continuing their pre-stroke antidepressant use.

Discussion

In this registry-based follow-up study on 888 young patients with first-ever IS, every fourth purchased antidepressants within the first year after stroke, mostly SSRIs. Moderate strokes compared with mild ones, limb paresis at discharge, silent infarcts, higher socioeconomic status, history of earlier antidepressant use, and current smoking increased the hazard for initiating PSAD.

The data especially on antidepressant use in young IS survivors are limited. In our study, the percentage of PSAD starters within the first year from IS (23%) corresponds with the post-stroke depression rates reported in previous studies including patients of any age, mainly older patients [1,2,3,4]. In the present study, median time to the first PSAD purchase from IS was around 3 months and SSRIs were the most frequently initiated antidepressants. Furthermore, those starting PSAD were more often older. Correspondingly, a large Danish cohort study found that stroke patients had a higher incidence of depression during the first 3 months after hospitalization compared with the reference population and that older age was significant risk factor for depression in both populations [6]. Similarly, in a recent study on 5070 consecutive first-ever ischemic stroke patients with a mean age of over 70 years [20], almost half of the previously untreated patients started antidepressant medication shortly after IS, the cumulative incidence of antidepressant treatment over 6 months post-stroke was 35%, and the most commonly prescribed antidepressants were SSRIs.

Furthermore, in that study [20], increasing stroke severity was associated with a higher likelihood of newly prescribed antidepressant after stroke. Association between stroke severity and initiating PSAD was also found in young individuals in our study. Those with moderate stroke symptoms at admission had higher hazard of starting PSADs compared to mild strokes. In addition, severe symptoms were associated with PSAD initiation univariately. However, this association was likely to be related to symptoms of limb paresis at hospital discharge, since 85% of those with severe stroke symptoms at admission had also limb paresis of some stage at discharge. Our study is in accordance with earlier findings that greater disability is associated with post-stroke depression not only in the general stroke population but also in younger individuals [2, 8, 25].

Silent infarcts and current smoking predicted the initiation of PSAD in our study, both of which can be indicators of poor lifestyle habits and poor adherence to self-care [26]. In accordance with our observations, one study found an association between silent lacunar infarction in basal ganglia and higher risk of depression [27]. Smoking is known to be associated with increased risk of depression in general [28, 29] and association between smoking and increased risk of post-stroke depression was reported recently [6, 30]. Furthermore, current smokers had higher NIHSS scores on admission in IS patients with small-vessel occlusions [31], but in our study, the frequencies of more severe strokes at admission did not differ significantly between smokers and non-smokers (data not shown). Heavy alcohol use was not associated with the initiation of PSAD in our study with relatively few heavy drinkers (n = 28, 13.6%) among patients initiating PSAD, but nor was it in a recent registry-based cohort study [6]. However, in these previous studies again, the age distribution is older compared to our study [6, 27, 30, 31]. The association between higher socioeconomic status and initiating PSAD in the present study might reflect a better compliance for starting antidepressant treatment. Expenses of the medicines are unlikely to be a significant reason not to purchase prescribed antidepressants among patients with lower socioeconomic status, since the costs are covered by the reimbursement system.

Our study has numerous strengths. It has a large study population of young patients with IS, detailed information on baseline stroke characteristics as well as other clinically important factors available. As an observational study, it brings the benefit of real-life setting compared to clinical trials. Data were collected from obligatory records required by health authorities, which reduces information bias. To assess the initiation of antidepressants, we excluded patients who had filled antidepressant prescriptions within 1 year prior to index stroke, since these patients were most likely continuing pre-stroke antidepressant use.

Also, we included only patients surviving the primary hospitalization period after IS and thus excluded 24 patients dying within the first 21 days. All of these patients died during the hospitalization, most of them (n = 20) within the first week after IS. Despite the fact that we had no information on actual compliance for antidepressant use, our study is likely to provide a good reflection of actual drug use, since our data consisted of only filled prescriptions and more than a half of the PSAD initiators had their second purchase within 3 months and over 3 of 4 initiators within 6 months, suggesting that those patients were also likely to become longer-term users. Furthermore, the present study has several methodological and analytical advantages, including a thorough assessment of the proportional hazards assumption and evaluation of the variation of both the ratio and rate of hazard of initiating PSAD over time.

Our study also has some inevitable limitations, and some sources of bias are challenging to control entirely due to its retrospective observational nature. It is noteworthy that the evidence on the value of the antidepressants for post-stroke depression and the range of different antidepressants available have remarkably changed over the long time period that our study covers. This presents some challenges in interpreting the results of the study and generalizing them when considering PSAD initiation occurred after this study. However, there were no consistent variations by calendar in initiation of PSAD (data not shown) and it is likely that the same factors are associated with PSAD initiation, since their association is not dependent on calendar time. This study assessed post-stroke (i.e., most likely stroke-related) initiation of antidepressants and accounted only PSAD started within the first year after IS. Although the data on antidepressant purchases prior to index IS did not reach up to 5 or more years in all patients, we estimated that approximately only 3 patients (9% of the previous antidepressant users) were potentially misclassified as a non-previous user. Even though the incidence of depression is still reported to be almost twice as high during the second year after stroke compared to reference population [6], the definition of starting PSAD applied in this study is relevant with respect to the research question on the post-stroke initiation of antidepressants. Despite it cannot be ruled out that PSAD started later than the first year after IS might be stroke-related in some individuals, by including also patients starting antidepressants after one or more years since IS death will most likely become a competing risk, unlike with our current method when the mortality rate within the first year after IS is low (n = 17, 1.9%). Furthermore, by focusing on PSAD initiated within the first year after IS, the results might be better utilized for post-stroke rehabilitation and follow-up. In our study population, 63% of PSAD initiators and 47% of non-initiators were discharged to institutional care or rehabilitation. We had no data on duration of the period of institutional rehabilitation and on the medication used during this time. However, institutional long-time hospitalization is less common in younger stroke patients compared to older population [32]. It is possible that some of those discharged to institutional rehabilitation started PSAD during this period and continued or stopped the use after institutional rehabilitation. The results form multivariable regression model including institutional rehabilitation suggested that the pattern of initiating PSAD was not affected by institutional rehabilitation (data not shown). Since the definition of initiating antidepressant use was based on filled prescriptions, we were not able to distinguish whether the indication for starting PSAD was depression, or some other reason, for example, to enhance neuroplasticity and promote stroke recovery. It is also possible that a patient diagnosed with depression had poor adherence to treatment and for this reason did not have any filled prescriptions. In addition, some possibly important risk factors for PSAD, such as diabetes [6], are relatively rare in younger population and thus the statistical power regarding these factors is limited.

In conclusion, even though additional research on young IS patients with larger study population, as well as prospective follow-up studies on post-stroke depression is needed to further assess the nature of our findings, we can conclude that previous history of depression as well as specific clinical characteristics are to be thoroughly assessed and post-stroke depression kept in mind in post-stroke rehabilitation and follow-up visits.

Data availability

We have documented the data, methods, and materials used to conduct the research in this report. The individual patient data are not publicly available because of legal restrictions.

Code availability

The syntax of the study analyses may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hackett ML, Yapa C, Parag V, Anderson CS (2005) Frequency of depression after stroke. Stroke 36:1330–1340. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000165928.19135.35

Ayerbe L, Ayis S, Wolfe CDA, Rudd AG (2013) Natural history, predictors and outcomes of depression after stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 202:14–21. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.107664

Towfighi A, Ovbiagele B, El Husseini N et al (2017) Poststroke depression: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000113

Ayerbe L, Ayis S, Crichton S (2014) The long-term outcomes of depression up to 10 years after stroke; the south london stroke register. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2013-306448

Mitchell AJ, Sheth B, Gill J et al (2017) Prevalence and predictors of post-stroke mood disorders: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of depression, anxiety and adjustment disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 47:48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.04.001

Jørgensen TSH, Wium-Andersen IK, Wium-Andersen MK et al (2016) Incidence of depression after stroke, and associated risk factors and mortality outcomes, in a large cohort of danish patients. JAMA Psychiat 73:1032–1040. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1932

Waje-Andreassen U, Thomassen L, Jusufovic M et al (2013) Ischaemic stroke at a young age is a serious event—final results of a population-based long-term follow-up in Western Norway. Eur J Neurol 20:818–823. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12073

Naess H, Nyland HI, Thomassen L et al (2005) Mild depression in young adults with cerebral infarction at long-term follow-up: a population-based study. Eur J Neurol 12:194–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00937.x

Ayerbe L, Ayis S, Crichton SL et al (2014) Explanatory factors for the increased mortality of stroke patients with depression. Neurology 83:2007–2012. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001029

Pan A, Sun Q, Okereke OI et al (2011) Depression and risk of stroke morbidity and mortality: a meta-analysis and systematic review. JAMA 306:1241–1249. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1282

Chemerinski E, Robinson RG, Kosier JT (2001) Improved recovery in activities of daily living associated with remission of poststroke depression. Stroke 32:113–117. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.32.1.113

Schmid AA, Kroenke K, Hendrie HC et al (2011) Poststroke depression and treatment effects on functional outcomes. Neurology 76:1000–1005. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318210435e

House A, Knapp P, Bamford J, Vail A (2001) Mortality at 12 and 24 months after stroke may be associated with depressive symptoms at 1 month. Stroke 32:696–701. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.32.3.696

Van De Weg FB, Kuik DJ, Lankhorst GJ (1999) Post-stroke depression and functional outcome: a cohort study investigating the influence of depression on functional recovery from stroke. Clin Rehabil 13:268–272. https://doi.org/10.1191/026921599672495022

Nannetti L, Paci M, Pasquini J et al (2009) Motor and functional recovery in patients with post-stroke depression motor and functional recovery in patients with post-stroke depression. Disabil Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280400009378

Naess H, Nyland H (2013) Poststroke fatigue and depression are related to mortality in young adults: a cohort study. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002404

Mortensen JK, Larsson H, Johnsen SP, Andersen G (2013) Post stroke use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and clinical outcome among patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke 44:420–426. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.674242

Juang HT, Chen PC, Chien KL (2015) Using antidepressants and the risk of stroke recurrence: report from a national representative cohort study. BMC Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-015-0345-x

Dam H, Harhoff M, Andersen PK, Kessing LV (2007) Increased risk of treatment with antidepressants in stroke compared with other chronic illness. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 22:13–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0b013e328010357f

Mortensen JK, Johnsen SP, Andersen G (2018) Prescription and predictors of post-stroke antidepressant treatment: a population-based study. Acta Neurol Scand 138:235–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12947

Aho K, Harmsen P, Hatano S et al (1980) Cerebrovascular disease in the community: results of a WHO collaborative study. Bull World Health Organ 58:113–130

Putaala J, Metso AJ, Metso TM et al (2009) Analysis of 1008 consecutive patients aged 15 to 49 with first-ever ischemic stroke: the Helsinki young stroke registry. Stroke 40:1195–1203. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.529883

Tilastokeskus—Luokitukset—Sosioekonominen asema (1989) Luokituksen kuvaus. http://www.stat.fi/meta/luokitukset/sosioekon_asema/001-1989/kuvaus.html. Accessed 21 Oct 2018

R Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Meng G, Ma X, Li L et al (2017) Predictors of early-onset post-ischemic stroke depression: a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol 17:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-017-0980-5

Putaala J, Kurkinen M, Tarvos V et al (2009) Silent brain infarcts and leukoaraiosis in young adults with first-ever ischemic stroke. Neurology 72:1823–1829. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a711df

Wu R-H, Li Q, Tan Y et al (2014) Depression in silent lacunar infarction: a cross-sectional study of its association with location of silent lacunar infarction and vascular risk factors. Neurol Sci 35:1553–1559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-014-1794-5

Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ (2010) Cigarette smoking and depression: tests of causal linkages using a longitudinal birth cohort. Br J Psychiatry 196:440–446. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065912

Flensborg-Madsen Trine T, Bay von Scholten M, Flachs EM et al (2011) Tobacco smoking as a risk factor for depression. A 26-year population-based follow-up study. J Psychiatr Res 45:143–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.06.006

Shi YZ, Xiang YT, Yang Y et al (2015) Depression after minor stroke: prevalence and predictors. J Psychosom Res 79:143–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.012

Weng WC, Huang WY, Chien YY et al (2011) The impact of smoking on the severity of acute ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci 308:94–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.046

Burton JK, Ferguson EEC, Barugh AJ et al (2018) Predicting discharge to institutional long-term care after stroke: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 66:161–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15101

Acknowledgements

Paula Bergman, Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. Bob Siegerink, Center for Stroke Research Berlin (CSB) Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Jessica Rohmann, Center for Stroke Research Berlin (CSB) Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Helsinki including Helsinki University Central Hospital. JB received support from Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District. KA received research support from the Finnish Medical Foundation and Maire Taponen Foundation. The principal investigator, JP received research support from Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District and Academy of Finland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JB designing the study, data collection, statistical analysis, writing the first version of the manuscript. KA supervising and designing the study, data collection, statistical analysis, editing the manuscript. AB planning data analysis, statistical analysis, editing the manuscript. IM designing the study, editing the manuscript. JR-P designing the study, editing the manuscript. MK designing the study, data collection, editing the manuscript. TT designing the study, data collection, editing the manuscript. JP funding, supervising and designing the study, data collection, statistical analysis, editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Jenna Broman reports no conflict of interest. Karoliina Aarnio reports no conflict of interest. Anna But reports no conflict of interest. Ivan Marinkovic reports no conflict of interest. Jorge Rodríguez-Pardo reports no conflict of interest. Markku Kaste reports no conflict of interest. Turgut Tatlisumak reports no conflict of interest. Jukka Putaala reports no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted retrospectively from data obtained for clinical purposes. The Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa approved the study protocol (73/13/03/00/11).

Consent to participate

Informed consent from patients in our cohort was not needed because the study is based on registry data without direct patient contacts.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Broman, J., Aarnio, K., But, A. et al. Initiation of antidepressants in young adults after ischemic stroke: a registry-based follow-up study. J Neurol 269, 956–965 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10678-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10678-4