Abstract

Propriospinal myoclonus (PSM) is a rare disorder with repetitive flexor, arrhythmic jerks of the trunk, hips and knees. Its generation is presumed to relay in the spinal cord. We report a case series of 35 consecutive patients with jerks of the trunk referred as possible PSM to a tertiary referral center for movement disorders. We review classical PSM features as well as psychogenic and tic characteristics. In our case series, secondary PSM was diagnosed in one patient only. 34 patients showed features suggestive of a psychogenic origin of axial jerks. Diagnosis of psychogenic axial jerks was based on clinical clues without additional investigations (n = 8), inconsistent findings at polymyography (n = 15), regular eye blinking preceding jerks (n = 2), or the presence of a Bereitschaftspotential (BP) (n = 9). In addition, several tic characteristics were noted. Almost all patients referred with possible PSM in our tertiary referral clinic had characteristics suggesting a psychogenic origin even in the presence of a classic polymyography pattern or in the absence of a BP. Clinical overlap with adult-onset tics seems to exist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Propriospinal myoclonus (PSM) is a rare disorder involving axial muscles [1]. It is classically characterized by arrhythmic, usually flexor jerks of the trunk, hips and knees that are often stimulus sensitive and typically increase when supine [1]. PSM is presumed to originate from a spinal generator that elicits activity spreading up and down the spinal cord, supposedly via intrinsic propriospinal pathways. Electrophysiological features include a fixed pattern of muscle activation, slow spinal cord conduction velocity (5–15 m/s), electromyographic (EMG) burst duration of less than 1,000 ms, synchronous activation of agonist and antagonist muscles, and no involvement of facial muscles [2]. Polymyography is regarded as an essential diagnostic procedure for PSM [2]. However, the very EMG pattern that is considered typical for PSM has been observed in healthy volunteers mimicking PSM and in a case of PSM with a probable psychogenic origin [3, 4].

As we frequently considered a psychogenic origin of axial jerks in patients referred to our tertiary referral center with possible diagnosis of PSM, we reviewed all consecutive referrals for both congruity and inconsistencies in the classical PSM features. Special attention is given to tic characteristics, as sensory warnings have been reported [5]. Moreover, we review electrophysiological recordings available and include follow-up.

Methods

Patient inclusion

We retrospectively (January 2000–October 2007) reviewed all consecutive patients (n = 39) that were considered to be PSM by the referring doctor and seen by hyperkinetic movement disorder specialists in our tertiary movement disorders clinic. Final diagnoses as found in the charts were registered. Clinical records, imaging and electrophysiological recordings were systematically scored. Position dependency, axial initiation and stimulus sensitivity of the jerks were considered suggestive of classical PSM [1, 5]. Facial musculature should not be involved in PSM. Acute onset of the disorder, rapid progression of symptoms after onset, spontaneous (albeit temporarily) remissions, previous somatizations, non-objectifiable (neurological) complaints and psychiatric co-morbidity, distractibility, variability (over time) and inconsistency (at time of visit) in the jerks and involvement of facial or neck muscles were considered suggestive of a psychogenic origin [6]. Premonitory sensations, urge, relieve, ability of jerk suppression and rebound were considered suggestive of a tic disorder.

Electrophysiological recordings

Polymyography included surface EMG recordings with 9 mm diameter Ag/AgCl electrodes of ten unilateral muscles: orbicularis oculi, sternocleidomastoid, biceps, extensor carpi radialis, the sixth thoracic vertebral level, the first lumbar vertebral level, rectus abdominus (both upper and lower), iliopsoas, tibialis anterior, and two others according to specific muscles involved in the individual patient, which could be the contralateral muscle of one of the muscles listed above. Recordings were performed with time-locked registration on video (Brainlab; OSG bvba, Rumst, Belgium). Jerk-locked back averaging was performed if jerk frequency was sufficient. In addition, patients were also asked to briefly voluntarily extend the dominant wrist every 5–10 s upon their own intention (no external triggering) at least 50–80 times. Sample frequency was 1,000 Hz and data was high pass filtered at 0.005 Hz. For jerk-locked back averaging surface EMG and electroencephalography (EEG) were recorded from six muscles (a selection of the muscles above) and the EEG montage included Cz, C3, C4, Fz, F3, F4 (referenced to linked-ears). We also used electro-oculography (EOG) to monitor eye movement and blinking. Triggers were set at burst onset of the initial muscle and the wrist extensor in the voluntary task. In case of inconsistent spontaneous jerking, the earliest involved muscle was used to mark the burst onset. For both the spontaneous jerks and for the intentional movements, all traces were divided into 4 s segments (2 s before to 2 s after jerk onset). All segments were visually inspected and trials with artefacts (e.g. eye blinks, movement artefact) were removed. In all patients at least 50 artefact free trials per condition (spontaneous jerk or intentional movement) were averaged. The Bereitschaftspotential (BP) was defined as a negative electrical shift over the central cortical areas that increased over time with amplitudes of at least 5 μV. Polymyographic recordings were scored for order of muscle recruitment, consistency of activation of the first muscle, consistency of pattern of spread of muscles involved (rostral and caudal after initial segment or ‘marche’), burst duration, and synchronous co-contraction of anta- and agonists [2]. Inconsistency was defined as differences in initial muscle and/or highly variable pattern of muscle activation.

Follow-up

All patients received standard follow-up at the outpatient clinic for at least half a year after final diagnosis was made. All patients were contacted via the telephone during April and May 2008. A standardized interview was performed to establish presence and severity of symptoms. Patients were asked to score the severity of the jerks on a ten point scale (0 = full remission) twice, the first score when seen at the outpatient clinic in the past and the second at present. In addition, all GPs were contacted, after written patient consent, to verify the patients account. During the telephone interview, we gathered medical details, natural course and any other alternative diagnosis made after a second/another opinion by another specialist.

Results

Out of 39 referred patients retrieved from the movement disorders database, five were excluded (three for inconclusive clinical or neurophysiological documentation). One patient was diagnosed with belly dancer's dyskinesia and was excluded. In the remaining 35 patients (18 men), characteristics suggestive of a psychogenic origin of the axial jerks were present. Median age was 47 years (range 17–83 years). Mean duration of symptoms was 43 months (median 20, range 1–360 months). In eight cases, the diagnosis of clinically definite psychogenic axial jerks was made. These patients had no additional electrophysiological investigations, or refused them (n = 2). One patient was diagnosed with secondary PSM (ciprofloxacin) (published previously) [7]. In the other 26 patients electrophysiological investigations supported a probable psychogenic origin.

PSM characteristics

Twenty-five patients had jerks when sitting and 24 of them also when lying down. In ten of these patients, jerks were more severe when lying down. Ten patients had axial flexion jerks when walking, one of them only had jerks when active (walking, knee buckling) and one only after (minimal) physical exercise. In four patients, facial musculature was involved in the jerks. During sleep none of our patients reported axial jerks, although this was not objectified by polysomnography. None of the patients had a history of restless legs syndrome (RLS) either nor periodic limb movements (PLMD) during sleep. Jerks were stimulus sensitive in seven patients.

Clinical clues suggestive of psychogenesis

Onset of jerks was acute in 26 cases; six patients had paroxysmal jerk attacks. One patient had had a spontaneous remission and one patient had already had spontaneous long symptom free periods. Fifteen patients had a psychiatric history. Two were diagnosed with bipolar disorder (once with a psychotic episode), three with depression, one patient had a history of sexual harassment and two others had been diagnosed with conversion disorder previously from other symptoms (psychogenic tremor and periodic weakness of legs with concomitant speech disturbances). Fourteen patients had multiple somatizations previously. Four of these patients had a history of previously unexplained neurological symptoms. Two of these patients still had subjective impaired vision, impaired coordination, weakness, blackouts and transient sensory deficits. Ten patients appeared emotionally disturbed at time of visit, and three of them had obvious severe psychiatric disturbances. During examination, 19 patients had clinically inconsistent muscle involvement and 28 had a variable pattern of jerks. Distractibility was noted in nine patients.

Tic clues

Fifteen patients had premonitory sensations, and 12 were able to temporarily suppress the jerks. Two patients had urge prior to jerk onset. Two other patients reported rebound after suppression and the same patients felt relieved after the jerks. None of these patients had had a history of motor or vocal tics.

Imaging and laboratory testing

In 27 patients a CT and MRI scan of the head and spinal cord revealed no abnormalities. Two patients refused imaging, and others (n = 5) were unable to lay still. CSF and laboratory testing were normal.

Electrophysiology

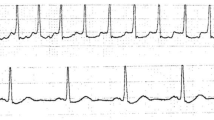

On polymyography (27 cases, one patient refused recordings), 15 patients showed inconsistencies, both in (order of) muscles involved, propagation of the muscle contraction (‘marche’) and duration of jerks. Frequency of jerks varied from once per day to once per 10 s. Some of our patients had ‘bouts’ or flurries of jerks. In 12 patients, a consistent pattern, defined as a consistent first muscle or topography was detected. Only six of them also had a rostral and caudal muscle spread on polymyography typical of PSM. More details on polymyography findings are listed in Table 2. In 17 patients, jerk-locked back averaging was performed. Nine patients with a consistent polymyography had a BP preceding their axial jerks (see Table 2). The three remaining patients with a consistent pattern of jerks did not exhibit a BP. Investigations and analysis were difficult in two patients as, in one of them, jerks were preceded by eye blinking and in the other patient, facial musculature contraction with eye blinking prior to the onset of axial jerks was noted. In none of the patients with an inconsistent pattern on polymyography (n = 5) was a BP found (see Table 2). Figures 1 and 2 display a BP preceding a consistent pattern of jerks and an example of an inconsistent polymyography. Additional SSEP recordings were performed in five patients, none of whom showed giant SSEPs.

Example of Bereitschaftspotential (BP) recording. EMG was triggered of the onset of the left deltoid muscle (initial muscle; rectified EMG displayed). One hundred sixty-nine events were averaged to resolve the BP. Premovement negativity was maximal at the vertex (Cz) and more prominent at C4 compared to C3

Illustration of polymyography recording of inconsistent jerks (single traces displayed, same patient). Jerks could start in the rectus abdominus muscle (RA) left (L) or right (R) and then spread to legs and neck and not the arms nor the eye musculature (OO orbicularis oculi muscle). Jerks were of variable duration and conduction was rapid. Other jerks confined to the one arm or the neck were also noted. APB abductor pollicis brevis muscle, L1 first lumbar, SCM sternocleidomastoid, TA tibialis anterior, Th thoracic, vastus vastus medialis muscle

Illustrative case report

A 62 year old female with a 1 year history of jerking of the trunk and limbs presented to our clinic for a second opinion. Her medical history consisted of a bipolar disorder, once accompanied by psychosis. Her current medication consisted of lithium, clonazepam and temazepam. Family history included a brother with epilepsy.

The truncal jerks had started acutely 30 min after coloring her hair, which subsequently lead the patient to try to prosecute the producing company. The pattern of jerks changed over time and jerks mainly appeared while lying supine. During the attacks she felt panic and could have unbalanced (not ataxic) walking afterwards. Jerks were accompanied by a premonitory sensory warning and she was able to suppress them, but no rebound occurred. During examination the jerks had a changing pattern and were distractible. Electrophysiology was not performed. Diagnosis of clinically definite psychogenic axial jerks was made, although influence of lithium could not be excluded. The patient was contacted via the telephone after 7 months. She had been treated by a psychiatrist and physiotherapist and had experienced a sudden remission while continuing lithium (unaltered dosage). A video can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Follow-up

Average time from discharge was 40 months (median 23 months, range: 3–104). Thirty out of 33 (one lost to follow-up, one refused participation) patients still had jerks (91%), but most of them to a lesser extent. The patients with continuing complaints rated it 8 out of 10 (SD: 1.4) for severity in the past when seen in the outpatient clinic, and 5 (SD: 1.7) at the time of the telephone call. Written consent of the patients was obtained to contact all GPs and their assessment concurred with the patients account. Moreover, none of the patients had received an alternative diagnosis (by another specialist or neurologist) that could explain the axial jerks.

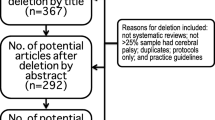

An overview of clinical work-up and final diagnoses of our case series is provided in Fig. 3. Results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Overview of the clinical work-up of the patients in our study. The case of PSM due to ciprofloxacin has been published previously [7]. BP Bereitschaftspotential, Jerk-locked BA jerk-locked back averaging, PSM propriospinal myoclonus, Psychogenic psychogenic axial jerks

Discussion

Our study suggests that axial jerks in most cases meet criteria for a psychogenic origin. PSM is a rare disorder and is presumed to be clinically homogenous [5]. Common etiologies of PSM are cervical lesions [5]. However, in 80% of the cases reported in the literature, etiology remains undetermined or speculative. Although PSM patients are usually not considered to have a tic or psychogenic disorder, atypical symptoms suggestive of these diagnoses such as grunting, tonic contractions of the eye musculature, long symptom free intervals, decrease of jerk frequency by mental arithmetic tasks and peculiar restless sensations prior to the jerks are often reported [5, 8, 9]. Interestingly, some patients in our case series with presumed psychogenic axial jerks were able to (briefly) suppress jerking (n = 12), had rebound after suppression (n = 2), premonitory sensations (n = 15) and urge (n = 2) prior to the onset of jerks. Our findings imply an overlap between psychogenic axial jerks and adult-onset motor tics. In our opinion, reported adult-onset tic disorders are rather atypical. For instance, Davies and colleagues reported a case of recumbent tics that is rather similar to some of our cases and its organic origin might be questioned [10, 11].

Defining of electrophysiological characteristics specific to PSM is difficult. In most reports on PSM, electrophysiological details are missing. This hampers comparison between studies and development of strict clinical and electrophysiological criteria for PSM. Duration of bursts, according to previous studies, is usually long but highly variable (between 20 and 4,000 ms) [4]. A slow conduction velocity over the spinal cord has been suggested to indicate involvement of polysynaptic propriospinal pathways, but these velocities can also be found in voluntarily mimicked PSM [4]. The reported electromyography findings raise the question of the exact nature of PSM, and may suggest a cortical (frontal) rather than a spinal origin of PSM in many patients indeed. In our series, we either found a BP or inconsistent jerking to support the possible psychogenic etiology.

Our case series may not be representative as it was collected in a specialized movement disorders center. Moreover, the accuracy of the differential diagnosis of PSM made by referring neurologists can, in hindsight, be questioned in some cases. This might be explained by the rareness of PSM and the heterogeneous descriptions of PSM in literature [5].

Moreover, in other reports, primarily ‘typical’ cases were included (for instance [5]) contributing to possible report bias. Nevertheless, we also encountered many ‘classical’ cases. The existence of a clinical spectrum of patients with axial jerks ranging from a true spinal origin to a tic-like disorder and psychogenic jerks is also illustrated in the literature, as many patients described with a diagnosis of PSM actually do not fit the classical description and/or show features that are not consistent with an organic origin [5, 8, 9]. It is unfortunate that not all of our patients received standardized additional investigations. It has been recently reported that diffusion tensor imaging of the spinal cord was abnormal in patients with PSM [5]. However, its use in clinical practice may be limited, as regular imaging of the spinal cord proved to be particularly difficult in our patients, as their axial flexion jerks posed too much movement artefact. In contrast, therefore, electrophysiological testing is the additional investigation of choice, including both polymyography and jerk-locked back averaging in case of isolated axial jerks.

In conclusion, our series of patients with axial flexion jerks may serve as an incentive to redefine the characteristics and diagnostic criteria for PSM.

References

Brown P, Thompson PD, Rothwell JC, Day BL, Marsden CD (1991) Axial myoclonus of propriospinal origin. Brain 114(Pt 1A):197–214

Chokroverty S, Walters A, Zimmerman T, Picone M (1992) Propriospinal myoclonus: a neurophysiologic analysis. Neurology 42(8):1591–1595

Kang SY, Sohn YH (2006) Electromyography patterns of propriospinal myoclonus can be mimicked voluntarily. Mov Disord 21(8):1241–1244

Williams DR, Cowey M, Tuck K, Day B (2008) Psychogenic propriospinal myoclonus. Mov Disord 23(9):1312–1313

Roze E, Bounolleau P, Ducreux D et al (2009) Propriospinal myoclonus revisited: clinical, neurophysiologic, and neuroradiologic findings. Neurology 72(15):1301–1309

Fahn S, Williams DT (1988) Psychogenic dystonia. Adv Neurol 50:431–455

Post B, Koelman JH, Tijssen MA (2004) Propriospinal myoclonus after treatment with ciprofloxacin. Mov Disord 19(5):595–597

Espay AJ, Ashby P, Hanajima R, Jog MS, Lang AE (2003) Unique form of propriospinal myoclonus as a possible complication of an enteropathogenic toxin. Mov Disord 18(8):942–948

Lozsadi DA, Forster A, Fletcher NA (2004) Cannabis-induced propriospinal myoclonus. Mov Disord 19(6):708–709

Eapen V, Lees AJ, Lakke JP, Trimble MR, Robertson MM (2002) Adult-onset tic disorders. Mov Disord 17(4):735–740

Davies L, King PJL, Leicester J, Morris JGL (1992) Recumbent tic. Mov Disord 7:359–363

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank J. Speelman M.D. Ph.D., neurologist in the AMC, for providing detailed patient records, T. Boerée for help with illustrations and M. Pleizier M.D. for valuable discussion.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary video: Patient demonstrates position dependant jerks of trunk, arms and legs. Jerks are inconsistent and vary in duration, muscle distribution and topography. (MPG 18171 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Salm, S.M.A., Koelman, J.H.T.M., Henneke, S. et al. Axial jerks: a clinical spectrum ranging from propriospinal to psychogenic myoclonus. J Neurol 257, 1349–1355 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5531-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5531-6