Abstract

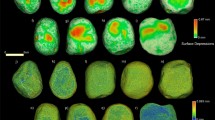

This experimental study provides a further understanding of the post-burning nature of sharp force trauma. The main objective is to analyse the distortion that fire may inflict on the length, width, roughness, and floor shape morphology of toolmarks induced by four different implements. To this end, four fresh juvenile pig long bones were cut with a bread knife, a serrated knife, a butcher machete, and a saw. A total of 120 toolmarks were induced and the bone samples were thus burnt in a chamber furnace. The lesions were analysed with a 3D optical surface roughness metre before and after the burning process. Afterwards, descriptive statistics and correlation tests (Student’s t-test and analysis of variance) were performed. The results show that fire exposure can distort the signatures of sharp force trauma, but they remain recognisable and identifiable. The length decreased in size and the roughness increased in a consistent manner. The width did not vary for the saw, serrated knife, or machete toolmarks, while the bread knife lesions slightly shrunk. The floor shape morphology varied after burning, and this change became more noticeable for the three knives. It was also observed that the metrics of the serrated knife and machete cut marks showed no significant variations. Our results demonstrate that there is a variation in the toolmark characteristics after burning. This distortion is dependent on multiple factors that influence their dimensional and morphological changes, and the preservation of class features is directly reliant upon the weapon employed, the trauma caused, and the burning process conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Alunni V, Grevin G, Buchet L, Quatrehomme G (2014) Forensic aspect of cremations on wooden pyre. Forensic Sci Int 241:167–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.05.023

Bohnert M, Rost T, Pollak S (1998) The degree of destruction of human bodies in relation to the duration of the fire. Forensic Sci Int 95:11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0379-0738(98)00076-0

Mayne Correia P (1996) Fire modification of bone. In: Haglund WD, Sorg MH (eds) Forensic taphonomy: the postmortem fate of human remains. CRC Press Inc., Boca Raton, pp 275–293

Thompson TJU (2004) Recent advances in the study of burned bone and their implications for forensic anthropology. Forensic Sci Int 146:S203–S205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.09.063

Symes SA, Dirkmaat DC, Ousley S et al (2012) Recovery and interpretation of burned human remains. BiblioGov 236

Fairgrieve SI (2008) Forensic cremation: recovery and analysis. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Ubelaker DH (2009) The forensic evaluation of burned skeletal remains: a synthesis. Forensic Sci Int 183:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.09.019

Emanovsky P, Hefner JT, Dirkmaat DC (2002) Can sharp force trauma to bone be recognized after fire modification? An experiment using Odocoileus virginianus (white-tailed deer) ribs. Proc Annu Meet Am Acad Forensic Sci 8:214–215

Koch S, Lambert J (2017) Detection of skeletal trauma on whole pigs subjected to a fire environment. J Anthropol Rep 02:1–7. https://doi.org/10.35248/2684-1304.17.2.113

Mata Tutor P, Márquez-Grant N, Villoria Rojas C et al (2020) Through fire and flames: post-burning survival and detection of dismemberment-related toolmarks in cremated cadavers. Int J Legal Med 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-020-02447-1

Franceschetti L, Mazzucchi A, Magli F et al (2021) Are cranial peri-mortem fractures identifiable in cremated remains? A study on 38 known cases. Leg Med 49:101850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2021.101850

Ochôa Rodrigues C, Ferreira MT, Matos V, Gonçalves D (2020) “Sex change” in skeletal remains: assessing how heat-induced changes interfere with sex estimation. Sci Justice 0–1.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scijus.2020.09.007

Gonçalves D, Thompson TJU, Cunha E (2013) Osteometric sex determination of burned human skeletal remains. J Forensic Leg Med 20:906–911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2013.07.003

Love JC (2019) Sharp force trauma analysis in bone and cartilage: a literature review. Forensic Sci Int 299:119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.03.035

Byers SN (2016) Sharp and miscellaneous trauma. In: Byers SN (ed) Introduction to forensic anthropology, 4th ed. Taylor & Francis, pp 320–335

Symes SA, Williams J, Murray E et al (2001) Taphonomic context of sharp-force trauma in suspected cases of human mutilation and dismemberment. In: Haglund WD, Sorg MH (eds) Advances in forensic taphonomy: method, theory, and archaeological perspectives. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 403–434

Symes SA, Chapman EN, Rainwater CW et al (2010) Knife and saw toolmark analysis in bone: a manual designed for the examination of criminal mutilation and dismemberment. Pennsylvania Mercyhurst Coll 142

Kimmerle EH, Baraybar JP (2008) Sharp force trauma. In: Taylor & Francis Inc (ed) Skeletal trauma: identification of injuries resulting from human rights abuse and armed conflict. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 263–314

Norman DG, Watson DG, Burnett B et al (2018) The cutting edge—micro-CT for quantitative toolmark analysis of sharp force trauma to bone. Forensic Sci Int 283:156–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2017.12.039

Ross AH, Radisch D (2019) Toolmark identification on bone. In: Dismemberments. Elsevier, pp 165–182

Saville PA, Hainsworth SV, Rutty GN (2007) Cutting crime: the analysis of the “uniqueness” of saw marks on bone. Int J Legal Med 121:349–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-006-0120-z

Love JC, Derrick SM, Wiersema JM, Peters C (2015) Microscopic saw mark analysis: an empirical approach. J Forensic Sci 60:S21–S26. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12650

Sanabria-Medina C, Osorio Restrepo H (2019) Dismemberment of victims in Colombia. In: Dismemberments. Elsevier, pp 7–41

Alunni-Perret V, Borg C, Laugier J-P et al (2010) Scanning electron microscopy analysis of experimental bone hacking trauma of the mandible. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 31:326–329. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181e2ed0b

Humphrey JH, Hutchinson DL (2001) Microscopic characteristics of hacking trauma. J Forensic Sci 46:228–233. https://doi.org/10.1520/JFS14955J

McCardle P, Stojanovski E (2018) Identifying differences between cut marks made on bone by a machete and katana: a pilot study. J Forensic Sci 63:1813–1818. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13754

de Gruchy S, Rogers TL (2002) Identifying chop marks on cremated bone: a preliminary study. J Forensic Sci 47:15506J. https://doi.org/10.1520/JFS15506J

Macoveciuc I, Márquez-Grant N, Horsfall I, Zioupos P (2017) Sharp and blunt force trauma concealment by thermal alteration in homicides: an in-vitro experiment for methodology and protocol development in forensic anthropological analysis of burnt bones. Forensic Sci Int 275:260–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2017.03.014

Pope EJ, Smith OC (2004) Identification of traumatic injury in burned cranial bone: an experimental approach. J Forensic Sci 49:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1520/JFS2003286

Poppa P, Porta D, Gibelli D et al (2011) Detection of blunt, sharp force and gunshot lesions on burnt remains. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 32:275–279. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAF.0b013e3182198761

Mata Tutor P, Benito Sánchez M, Villoria Rojas C et al (2021) Cut or burnt?–categorizing morphological characteristics of heat-induced fractures and sharp force trauma. Leg Med 50:101868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2021.101868

Alunni V, Nogueira L, Quatrehomme G (2018) Macroscopic and stereomicroscopic comparison of hacking trauma of bones before and after carbonization. Int J Legal Med 132:643–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-017-1649-8

Herrmann NP, Bennett JL (1999) The differentiation of traumatic and heat-related fractures in burned bone. J Forensic Sci 44:14495J. https://doi.org/10.1520/JFS14495J

Kooi RJ, Fairgrieve SI (2013) SEM and stereomicroscopic analysis of cut marks in fresh and burned bone. J Forensic Sci 58:452–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12050

Marciniak S-M (2009) A preliminary assessment of the identification of saw marks on burned bone. J Forensic Sci 54:779–785. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2009.01044.x

Robbins SC, Fairgrieve SI, Oost TS (2015) Interpreting the effects of burning on pre-incineration saw marks in bone. J Forensic Sci 60:S182–S187. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12580

Vegh EI, Rando C (2018) Effects of heat as a taphonomic agent on kerf dimensions. Archaeol Environ Forensic Sci 1:105–118. https://doi.org/10.1558/aefs.35927

Waltenberger L, Schutkowski H (2017) Effects of heat on cut mark characteristics. Forensic Sci Int 271:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.12.018

Thompson TJU (2005) Heat-induced dimensional changes in bone and their consequences for forensic anthropology. J Forensic Sci 50:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1520/JFS2004297

Ellingham STD, Thompson TJU, Islam M, Taylor G (2015) Estimating temperature exposure of burnt bone—a methodological review. Sci Justice 55:181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scijus.2014.12.002

Bonney H, Goodman A (2020) Validity of the use of porcine bone in forensic cut mark studies. J Forensic Sci 1556–4029:14599. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.14599

Pearce A, Richards R, Milz S et al (2007) Animal models for implant biomaterial research in bone: a review. Eur Cells Mater 13:1–10. https://doi.org/10.22203/eCM.v013a01

Matuszewski S, Hall MJR, Moreau G et al (2020) Pigs vs people: the use of pigs as analogues for humans in forensic entomology and taphonomy research. Int J Legal Med 134:793–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-019-02074-5

Rainwater CW (2015) Three modes of dismemberment: disarticulation around the joints, transection of bone via chopping, and transection of bone via sawing. Skeletal trauma analysis. Wiley, Chichester, pp 222–245

Konopka T, Strona M, Bolechała F, Kunz J (2007) Corpse dismemberment in the material collected by the Department of Forensic Medicine, Cracow, Poland. Leg Med 9:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2006.08.008

Mata Tutor P, Villoria Rojas C (2020) Vayamos por partes-Desmembramiento y mutilación en España en los últimos 10 años. V Anu Int Criminol y Ciencias Forenses, SECCIF 5:165–185

Wilke-Schalhorst N, Schröder AS, Püschel K, Edler C (2019) Criminal corpse dismemberment in Hamburg, Germany from 1959 to 2016. Forensic Sci Int 300:145–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.04.038

Black S, Rutty G, Hainsworth S, Thomson G (2017) Introduction to criminal human dismemberment. In: Black S, Rutty G, Hainsworth S, Thomson G (eds) Criminal dismemberments, 1st edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 1–6

Mata Tutor P, Márquez-Grant N, Villoria Rojas C et al (Under review) Cadaver dismemberment and posterior destructive alteration as a method of body disposal in Spanish forensic cases. J Forensic Leg Med

Vazquez-Calvo C, Alvarez de Buergo M, Fort R, Varas-Muriel MJ (2012) The measurement of surface roughness to determine the suitability of different methods for stone cleaning. J Geophys Eng 9:S108–S117. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-2132/9/4/S108

Miller AZ, Rogerio-Candelera MA, Dionísio A et al (2012) Evaluación de la influencia de la rugosidad superficial sobre la colonización epilítica de calizas mediante técnicas sin contacto. Mater Construcción 62:411–424. https://doi.org/10.3989/mc.2012.64410

Ellingham S, A. Sandholzer M, (2020) Determining volumetric shrinkage trends of burnt bone using micro-CT. J Forensic Sci 65:196–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.14150

Vassalo AR, Mamede AP, Ferreira MT et al (2019) The G-force awakens: the influence of gravity in bone heat-induced warping and its implications for the estimation of the pre-burning condition of human remains. Aust J Forensic Sci 51:201–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00450618.2017.1340521

Báez Calderón A (2018) Aplicación de peróxido de hidrógeno al 40% con o sin activadores y su efecto sobre esmalte, estudio in vitro al rugosímetro. Universidad Central del Ecuador (Bachelor Thesis)

Casanova X, Roldán M, Subirà ME (2020) Analysis of cut marks on ancient human remains using confocal profilometer. J Hist Archaeol Anthropol Sci 5:18–26. https://doi.org/10.15406/jhaas.2020.05.00213

Porta D, Amadasi A, Cappella A et al (2016) Dismemberment and disarticulation: a forensic anthropological approach. J Forensic Leg Med 38:50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2015.11.016

Thompson TJU, Inglis J (2009) Differentiation of serrated and non-serrated blades from stab marks in bone. Int J Legal Med 123:129–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-008-0275-x

Stanley SA, Hainsworth SV, Rutty GN (2018) How taphonomic alteration affects the detection and imaging of striations in stab wounds. Int J Legal Med 132:463–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-017-1715-2

Acknowledgements

This experiment is adhered to the British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology guidance on Ethics and Practice. We would like to express our gratitude to the members of Petrophysics Laboratory at Geosciences Institute (CSIC, UCM) for the technical assistance provided during the use of the optical roughness metre and the electric furnace. We kindly thank Iván Serrano Muñoz for his help and patience during the burning process. Lastly, we thank Daniel García Rubio for his assistance in designing the tables and figures and for providing the samples.

Funding

This experiment was funded by the British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology research grant (2020–2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Pilar Mata Tutor: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, software, formal analysis and interpretation, visualisation, writing—original draft, writing—editing, funding acquisition; Catherine Villoria Rojas: methodology, software, formal analysis and interpretation, visualisation; Nicholas Marquéz-Grant: supervision, writing—editing; Mónica Álvarez del Buergo Ballester: software, resources; Natalia Pérez Ema: software, resources; María Benito Sánchez: supervision, writing—editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This is not applicable as this experiment adhered to the British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology guidance on Ethics and Practice.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Highlights

• Fire exposure can distort the signatures of sharp force trauma.

• Toolmark’s length decreased in size and roughness increased in a consistent manner.

• Serrated knife and machete cut marks metrics showed no significant variations.

• Roughness metre is a valid non-destructive device that may complement the toolmark analysis.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mata-Tutor, P., Villoria-Rojas, C., Márquez-Grant, N. et al. Measuring dimensional and morphological heat alterations of dismemberment-related toolmarks with an optical roughness metre. Int J Legal Med 136, 343–356 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-021-02627-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-021-02627-7