Abstract

Purpose

A procedure is needed for bodies with disfiguring injuries to the face and the use of their portrait for visual identification.

Method

We present the application of a simple image processing procedure, otherwise known as ”bubbling,” which is based on the concept of ”perceptual filling-in,” to images for visual identification in the forensic context. The method is straight forward and can be performed using readily available software and hardware..

Results

The method is demonstrated and examples are shown. The visual recognition of known persons using “bubbled” images was successfully tested.

Conclusion

The “bubbling” procedure for visual identification enhancement is quick and straightforward and may be attempted before escalating to more involved identification methods and procedures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The practice of visual identification (ID) of dead bodies is performed in forensic medicine under various circumstances, for example, mass death scenarios [1,2,3,4]. Despite reports of high error rates of 50% [5], visual ID may be “the only pragmatic option” [6] in some scenarios. In routine autopsy practice, visual ID is performed before autopsy and is generally reliable [7]. In some countries, such visual ID by relatives or any recognizant person is mandatory [8]. The psychological effect on relatives is mixed [9]. Reconstruction, thanatopraxy, or modern embalming techniques may be necessary [10, 11]. Visual ID may be used to identify unknown bodies in morgues [12], and in some countries, the publication of postmortem portraits in different media is a standard procedure [13]. Media publication may also be considered in criminal investigation cases involving unknown bodies, if alternative measures fail for one reason or another. This is however seen as problematic in western cultures, especially in cases with facial trauma. Testing the feasibility of a method called ”bubbling” to correctly recognize and identify a known person after removing trauma stigmata from images was our goal.

Method

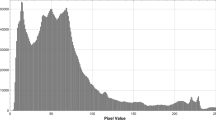

Visual recognition is a complex process, which involves a mechanism known as perceptual filling-in, where “a visual attribute [...] is perceived in a region of the visual field even though such an attribute exists only in the surround” [14]. The brain fills in the gaps, based on experience. This principle has been applied unscientifically in online forums to generate proxy-nudity out of harmless source images, in a process dubbed ”bubbling.” Usually in bubbling, harmless images of a target person wearing swimwear or other light clothing is used as the source. Desired content (skin) is selected while undesired content (clothing) in non-selected residual spaces is faded out to create proxy-nudity. The use of round or ellipsoid selections (”bubbles”) seems to promote this process by creating an unobtrusive mesh of organically shaped residual spaces (see Fig. 1, for example). The technical application of the bubbling procedure is straightforward, including the application for facial recognition. A basic image manipulation program is needed (Photoshop®, Paintshop®, GIMP). Then, round- or ellipsoid-shaped selections (”bubbles”) are drawn around undisturbed areas, while undesired (in our case traumatized) space is left unselected. At first, as large as possible bubbles are selected, followed by smaller bubbles in between selections until most of the desired content is selected. Now, this selection is inverted and the residual space in between bubbles is painted in or otherwise obscured, for example using large-scale pixelation. Original color should be retained, since skin tones and hair color may contribute to the identification. De-saturation/gray scaling of bubble content may however be necessary for prominent lividity, bruising, decomposition, or other distracting discolorations (see Fig. 2 for an overview of the process (using GIMP) and Fig. 3 for a result example).

Results

The general recognition of “bubbled” portraits was tested in an experimental setting. Two student groups from Homburg (N=38) and Budapest (N=15) were presented with 10 bubbled portraits of national and international public figures in quick succession. For each, the students had to either note the name of the person or mark it “not recognized.” After all bubbled pictures were shown, the unaltered original images were shown and the students could note “I do not know this person” if in fact they did not.Footnote 1 Different outcomes had to be considered:

-

(1)

A known person was recognized correctly (“It was A, I knew it!”).

-

(2)

A known person was mistaken for another known person (“I thought it was A, but now I see it is B.”).

-

(3)

A known person was not recognized (“I did not see that it was A.”).

-

(4)

An unknown person was not recognized (“Never seen, no idea!”).

-

(5)

An unknown person was wrongly identified as another person (“Not B? Then I don’t know!”).

The total count of queries was 530 (53 × 10). The public figure was confirmed to be known by the student in 382 cases (72.1%). Out of those, 255 queries (66.8%) were recognized correctly, 33 (8.6%) were mistaken for another celebrity, and 94 (24.6%) were not identified.

Discussion

Many portraits of cases with disturbing, yet circumscribed facial trauma can be treated efficiently and effectively for possible publication by unobtrusively fading out findings. Depending on the individual case, recognition rates are potentially high, as suggested by the outcome of our experiment. In violent mass death such as terror attacks and train accidents, the method may assist in the identification of victims (and perpetrators), especially when for one reason or the other sufficient other means of identification are unavailable. The method may be applied to electronic images quickly and easily, using readily available software and hardware. As far as can be said following our experiment, the method works best with limited, circumscribed findings such as gunshot wounds, cuts, and lacerations. It is advisable to salvage presentable fractions of features whenever possible to retain features such as shape, position, and size for eyes, nose, ears, hairline and others, even if a larger extent of said features is distorted. Use of pre-autopsy, pre-cleaning pictures might sometimes be beneficial for identification (noticeable head wear, make up, jewelry, and clothing). Bloodstains or damage on objects may be included into the ”bubbling” process. Generalized findings without “gaps to fill,” such as swelling, bloating, and discoloration as well as grotesque deformations cannot be improved by the procedure. As to how much visual information may be omitted in the grid depends both on the case and the viewer, so no general rules can be given. However, if large portions of the face must be left blank when ”bubbling,” alternative methods such as forensic artwork, sophisticated image processing, or facial reconstruction techniques may be more suitable.

Conclusion

The “bubbling” procedure is a fast, inexpensive identification enhancement technique which may be attempted before escalating to more involved procedures.

Notes

Celebrities included Lothar Matthäus (soccer player/ coach), Ursula von der Leyen (politician), Heidi Klum (model), Viktor Orbán (politician), Bruce Lee (actor), Greta Thunberg (political activist), Pope Francis, Tom Cruise (actor), Rihanna (singer), Frauke Petry (politician), and Inka Bause (TV presenter). In addition, one person known as a tutor was included as well as one person who was not a public figure and completely unknown to the students (as a control).

References

Wright K, Mundorff A, Chaseling J, Forrest A, Maguire C, Crane DI (2015) A new disaster victim identification management strategy targeting “near identification-threshold” cases: experiences from the Boxing Day tsunami. Forensic Sci Int 250:91–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.03.007

Morgan OW, Sribanditmongkol P, Perera C, Sulasmi Y, Van Alphen D, Sondorp E (2006) Mass fatality management following the South Asian tsunami disaster: case studies in Thailand, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka. PLoS Med 3:e195. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030195

Mcentire D, Sadiq AA, Gupta K (2012) Unidentified Bodies and Mass-Fatality Management in Haiti: A Case Study of the January 2010 Earthquake with a Cross-Cultural Comparison. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters 01:30. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2012.0123

Gunawardena SA, Samaranayake R, Dias V, Pranavan S, Mendis A, Perera J (2019) Challenges in implementing best practice DVI guidelines in low resource settings: lessons learnt from the Meethotamulla garbage dump mass disaster. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 15:125–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-018-0033-4

Lain R, Griffiths C, Hilton JMN (2003) Forensic dental and medical response to the Bali bombing. A personal perspective. Med J Aust 179:362–365. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05594.x

The international Committee of the Red Cross, ICRC (2009) Missing people, DNA analysis and identification of human remains - A guide to best practice in armed conflicts and other situations of armed violence. https://www.icrc.org/en/publication/4010-missing-people-dna-analysis-and-identification-human-remains-guide-best-practice. Accessed 5 Feb 2021

Bassendale M (2009) Disaster Victim Identification After Mass Fatality Events: Lessons Learned And Recommendations For The British Columbia Coroners Service. https://www.royalroads.ca/sites/default/files/tiny_files/M__Bassendale_MRP_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2021

Uzün I, Daregenli O, Sirin G, Müslümanoğlu O (2012) Identification procedures as a part of death investigation in Turkey. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 33:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAF.0b013e3182243eae

Chapple A, Ziebland S (2010) Viewing the body after bereavement due to a traumatic death: qualitative study in the UK. BMJ. 340:c2032. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c2032

Hejna P, Safr M, Zátopková L (2011) Reconstruction of devastating head injuries: a useful method in forensic pathology. Int J Legal Med 125:587–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-011-0553-x

Joukal M, Frišhons J (2015) A facial reconstruction and identification technique for seriously devastating head wounds. Forensic Sci Int 252:82–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.04.027

Hanzlick R (2006) Identification of the unidentified deceased and locating next of kin: experience with a UID web site page, Fulton County, Georgia. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 27:126–128. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.paf.0000221069.55267.05

Yadav A, Kumar A, Swain R, Gupta SK (2017) Five-year study of unidentified/unclaimed and unknown deaths brought for medicolegal autopsy at Premier Hospital in New Delhi, India. Med Sci Law 57:33–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0025802416680523

Komatsu H (2006) The neural mechanisms of perceptual filling-in. Nat Rev Neurosci 7:220–231. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1869

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Theoretical study, no ethical approval necessary.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key points

We present a method to unobtrusively conceal facial trauma in dead body portraits.

The method (“bubbling”) was originally used by individuals online to create “proxy-nudity” by fading out clothing.

The method is quick and simple and requires only simple software and hardware.

“Bubbled” portraits of celebrities had high recognition rates when tested on students.

The method may be attempted for visual identification before escalating to more involved procedures.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Potente, S., Ramsthaler, F., Kettner, M. et al. Application of the “bubbling” procedure to dead body portraits in forensic identification. Int J Legal Med 135, 1655–1659 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-021-02515-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-021-02515-0