Abstract

Ancestry inference for an individual can only be as good as the reference populations with allele frequency data on the SNPs being used. If the most relevant ancestral population(s) does not have data available for the SNPs studied, then analyses based on DNA evidence may indicate a quite distantly related population, albeit one among the more closely related of the existing reference populations. We have added reference population allele frequencies for 14 additional population samples (with >1100 individuals studied) to the 125 population samples previously published for the Kidd Lab 55 AISNP panel. Allele frequencies are now publicly available for all 55 SNPs in ALFRED and FROG-kb for a total of 139 population samples. This Kidd Lab panel of 55 ancestry informative SNPs has been incorporated in commercial kits by both ThermoFisher Scientific and Illumina for massively parallel sequencing. Researchers employing those kits will find the enhanced set of reference populations useful.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Soundararajan et al. [1] recently highlighted the limited utility of the many published ancestry informative SNP (AISNP) panels. The review identified 21 publications reporting different SNP panels for ancestry inference. The union of SNPs in the 21 published panels consisted of 1397 SNPs of which only 46 occurred in three to six panels. No SNP occurred in more than six of the 21 panels. Also, relatively few ethnic groups had been studied on any common set of SNPs making comparisons and likelihood calculations difficult to impossible for forensic ancestry applications. The development efforts underlying some panels involved examining population samples from only a few very different world regions. The review concluded that there is little need for more new ancestry panels focused on inferring ancestry to a handful of major world geographical regions. What is needed is a coordination of efforts to greatly expand the ethnic populations with published SNP frequency data on the panels with the best worldwide coverage of human diversity. Soundararajan et al. (2016) [1] note that the 128 AISNPs from the Seldin group [2, 3] and our Kidd Lab set of 55 AISNPs [4, 5] at present have the largest numbers of reference populations with the broadest coverage of major world regions.

Here, we report on 14 additional population samples with allele frequencies on all of the 55 AISNPs in the Kidd lab panel [4]. ALFRED and FROG-kb now have a total of 139 reference populations that have allele frequencies on all 55 of the Kidd panel AISNPs.

Materials and methods

The 14 new populations are listed in Table 1 with the sample size, the laboratory generating the data, and the typing method employed. Supplementary Table S1 lists the 139 different population samples representing the diverse ethnic groups and biogeographic regions that have now been analyzed for these 55 AISNPs. The populations in the table are organized by geographic region. The table also includes the number of individuals, the three-character abbreviations used in illustrations, and the unique sample identifier (UID) in the ALFRED database for looking up the description of each sample.

Every locus-population combination for which individual genotypes were available was tested for Hardy-Weinberg on the assumption that each locus was a codominant di-allelic genetic system. Genotypes were examined to ensure that the alleles on the positive strand have been entered into the database and are used in FROG-kb.

The STRUCTURE [10] software provides one way of assessing how well a set of loci tested on multiple individuals can infer ancestry. We employed version 2.3.4 applying the standard admixture model assuming correlated allele frequencies. At each K value from 6 to 10, the program was run 20 times with 10,000 burn-ins and 10,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) iterations.

Results

No significant deviations from Hardy-Weinberg ratios were observed beyond those expected by chance. All of the different typing methods appeared consistent: the same alleles are being detected at the same loci. Allele frequencies for the complete set of 55 SNPs in all 139 population samples are accessible in ALFRED. Additional populations have been studied and reported in scientific publications for some of the SNPs, and thus, some SNPs have frequency data on more than 139 population samples in ALFRED. In FROG-kb, the “Kidd Lab—Set of 55 AISNPs” has complete allele frequency data on all 55 SNPs for all 139 reference population samples. The completeness of the data allows likelihoods and likelihood ratios to be calculated for all of these 139 population samples for any input DNA profile for the 55 AISNPs (or a subset of the SNPs).

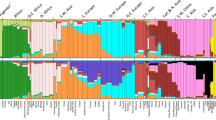

The STRUCTURE analysis result displayed in Fig. 1 is for the highest likelihood run of the most commonly occurring (for 10 of 20 runs) cluster pattern at K = 9. This analysis includes 66 additional populations since the previously reported analysis of only 73 populations [4]. The analysis of 139 reference populations included 8055 individuals after excluding individuals with an excessive number of missing genotypes. Of the 8055 individuals analyzed, 72.3% had all 55 AISNP genotypes present; 91.0% of individuals had no more than three missing typings; 1.9% of the 55 × 8055 possible genotypes were missing. The new populations generally show strong similarity to previously analyzed populations that were known to be closely related. In addition, a group of related populations from a previously underrepresented region can clearly define a new cluster, witness the North African cluster. Another interesting new clinal pattern across clusters for East Asian populations is seen for the ethnic minority populations sampled in Southwestern China—primarily Tibet, Yunnan, and Sichuan provinces. Elsewhere, a group of populations from Central Asia appears similar but shows partial similarity to several of the inferred clusters that predominate among populations in the surrounding geographical regions.

STRUCTURE results for estimated cluster membership values at K = 9 in 139 reference populations. Population abbreviations are explained in Table S1

Discussion and conclusions

With nearly twice as many population samples, we can see significant differences when that previously published STRUCTURE result [4] is compared with this new one. The 55 AISNP panel now shows that an additional cluster is defined by the North African populations recently included [5], consistent with the findings based on many more SNPs, that these North African populations form a genetically distinct cluster [11]. The large number of additional East Asian populations begins to show variation among the populations with Tibetans and other ethnic groups from Southwest China having a pattern of ancestral similarity that is quite visually distinct. Strong frequency differences at five SNPs (near ADH1B, ALDH2, OCA2, RPS28P8) underlie the Southwest China pattern obtained from STRUCTURE. The Southwest China pattern we have observed may correspond to the distinctive ethnic patterns reported for a study of mitochondrial DNA in 115 populations in Southern Asia [12]. They reported an interesting clustering of distinctive haplotypes centered on Myanmar and Southwest China.

Our interpretation of the multiple cluster memberships for populations in Central Asia is that this set of AISNPs does not work well to distinguish Central Asian populations from populations to the East, South, and West. While, historically, Central Asia has seen many migrations, it has been inhabited since modern humans first reached this far in their expansion from Africa before they reached East Asia. How much the historical migrations are responsible compared to these simply being intermediate and not well differentiated by these SNPs is a question for future research.

In our update on the growing number of reference populations studied for the 55 AISNPs [5], our previous conclusion remains very relevant; specifically, “The ideal forensic ancestry inference resource will consist of a large number of highly informative AISNPs with full data on a large number of population samples representing all regions of the world.” Finding the best and most appropriate ancestry match for an individual in forensic work depends on having a comprehensive set of reference populations from around the world. Many more reference populations are needed. As various relatively neglected geographical regions and smaller ethnic groups in better studied areas are added, we will likely observe more interesting new cluster patterns and novel clinal variations. Such new findings will offer fresh opportunities to improve and fine-tune the best AISNP panels that will develop.

We continue to work on our own and with our collaborators to study more new populations on the 55 AISNP panel. We also continue to assess other SNPs for ancestry informativeness and whether they can improve refined ancestry inference by modifying the existing panel. We continue to encourage other researchers to consider adding their unique populations to this growing dataset of population samples which are all tested for the same set of ancestry informative SNPs. Similarly, we encourage others with excellent candidate AISNPs to request that we test them on our population samples.

These results demonstrate the value of more populations studied for a small number of informative SNPs. To date, no other panel of AISNPs has data on such a large number of populations distributed as widely. That does not mean this panel should be considered a final panel. There are other panels, noted above, that are also included in ALFRED and FROG-kb. We are working to increase reference population coverage of those panels as well so that the most globally informative subset of SNPs can be identified from the union.

References

Soundararajan U, Yun L, Shi M, Kidd KK (2016) Minimal SNP overlap among multiple panels of ancestry informative markers argues for more international collaboration. Forensic Sci Int Genet 23:25–32

Kosoy R, Nassir R, Tian C, White PA, Butler LM, Silva G, Kittles R, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Gregersen PK, Belmont JW, De La Vega FM, Seldin M (2009) Ancestry informative marker sets for determining continental origin and admixture proportions in common populations in America. Hum Mutat 30(1):69–78. doi:10.1002/humu.20822

Kidd JR, Friedlaender FR, Speed WC, Pakstis AJ, De La Vega FM, Kidd KK (2011) Analyses of a set of 128 ancestry informative single-nucleotide polymorphisms in a global set of 119 population samples. Investig Genet 2(1):1. doi:10.1186/2041-2223-2-1

Kidd KK, Speed WC, Pakstis AJ, Furtado MR, Fang R, Madbouly A, Maiers M, Middha M, Friedlaender FR, Kidd JR (2014) Progress toward an efficient panel of SNPs for ancestry inference. Forensic Science International: Genetics 10:23–32

Pakstis AJ, Haigh E, Cherni L, Ben Ammar ElGaaied A, Barton A, Evsanaa B, Togtokh A, Brissenden J, Roscoe J, Bulbul O, Filoglu G, Gurkan C, Meiklejohn KA, Robertson JM, Li C-X, Wei Y-L, Li H, Soundararajan U, Rajeevan H, Kidd JR, Kidd KK (2015) 52 additional reference population samples for the 55 AISNP panel. Forensic Sci Int Genet 19:269–271

Ercan-Sencicek AG, Jambi S, Franjic D, Nishimura S, Li M, El-Fishawy P, Morgan TM, Sanders SJ, Bilguvar K, Suri M, Johnson MH, Gupta AR, Yuksel Z, Mane S, Grigorenko E, Picciotto M, Alberts AS, Gunel M, Sestan N, State MW (2015) Homozygous loss of DIAPH1 is a novel cause of microcephaly in humans. Eur J Hum Genet 23:165–172

Gabriel S, Ziaugra L, Tabbaa D (2009) SNP genotyping using the Sequenom MassARRAY iPLEX platform. Current Protocols in Human Genetics Chapter 2: Unit 2.12

Themudo GE, Smidt Mogensen H, Børsting C, Morling N (2016) Frequencies of HID-ion ampliseq ancestry panel markers among greenlanders. Forensic Sci Int Genet 24:60–64. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2016.06.001

Wendt FR, Churchill JD, Novroski NMM, King JL, Ng J, Oldt RF, McCulloh KL, Weise JA, Smith DG, Kanthaswamy S, Budowle B (2016) Genetic analysis of the Yavapai Native Americans from West-Central Arizona using the Illumina MiSeq FGxTM forensic genomics system. Forensic Sci Int Genet 24:18–23

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155(2):945–959

Cherni L, Pakstis AJ, Boussetta S, Elkamel S, Frigi S, Khodjet-El-Khil H, Barton A, Haigh E, Speed WC, Ben Ammar Elgaaied A, Kidd JR, Kidd KK (2016) Genetic variation in Tunisia in the context of human diversity worldwide. Am J Phys Anthropology 161(1):62–71

Li Y-C, Wang H-W, Tian J-Y, Liu L-N, Yang L-Q, Zhu C-L, Wu S-F, Kong Q-P, Zhang Y-P (2015) Ancient inland human dispersals from Myanmar into interior East Asia since the Late Pleistocene. Scie Rep 5, Article#9473. DOI:10.1038/srep09473

Electronic resources cited

ALFRED: https://alfred.med.yale.edu

FROG-kb: https://frog.med.yale.edu

1000 Genomes project: http://www.1000genomes.org

Acknowledgements

The assembly and analyses of the data were funded primarily by NIJ Grants 2013-DN-BX-K023 and 2014–DN-BX-K030 to KKK awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice, and Grant BCS-1444279 from the US National Science Foundation. Points of view in this presentation are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. National Natural Science Foundation of China grants (31260252, 31760097, 31660307) to LK supported data collection. Acknowledgements for the collection of the individual sets of data are in the publications cited. Only the data for the eight new East Asian populations and the UAE Arabs are not fully published as yet and have been made available by the coauthors (LL, KK, ZZ, TJ, SH, MSQ) for this summary in advance of their full papers. Special thanks are due to the many hundreds of individuals who volunteered to give blood or saliva samples for studies of gene frequency variation and to the many colleagues who helped us collect the samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pakstis, A.J., Kang, L., Liu, L. et al. Increasing the reference populations for the 55 AISNP panel: the need and benefits. Int J Legal Med 131, 913–917 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-016-1524-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-016-1524-z