Abstract

Purpose

Metal and chemical exposure can cause acute and chronic respiratory diseases in humans. The purpose of this analysis was to analyze 14 types of urinary metals including mercury, uranium, tin, lead, antimony, barium, cadmium, cobalt, cesium, molybdenum, manganese, strontium, thallium, tungsten, six types of speciated arsenic, total arsenic and seven forms of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and the link with self-reported emphysema in the US adult population.

Methods

A cross-sectional analysis using the 2011–2012, 2013–2014 and 2015–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey datasets was conducted. A specialized weighted complex survey design analysis package was used in analyzing the data. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess the association between urinary metals, arsenic, and PAHs and self-reported emphysema among all participants and among non-smokers only. Models were adjusted for lifestyle and demographic factors.

Results

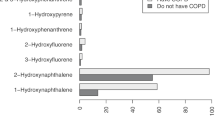

A total of 4,181 adults were analyzed. 1-Hydroxynaphthalene, 2-hydroxynaphthalene, 3-hydroxyfluorene, 2-hydroxyfluorene, 1-hydroxypyrene, and 2 & 3-hydroxyphenanthrene were positively associated with self-reported emphysema. Positive associations were also observed in cadmium and cesium with self-reported emphysema. Among non-smokers, quantiles among 2-hydroxynaphthalene, arsenocholine, total urinary arsenic, cesium, and tin were associated with increased odds of self-reported emphysema. Quantiles among 1-hydroxyphenanthrene, cadmium, manganese, lead, antimony, thallium, and tungsten were associated with an inverse relationship with self-reported emphysema in non-smokers.

Conclusion

The study determined that six types of urinary PAHs, cadmium, and cesium are positively associated with self-reported emphysema. Certain quantiles of 2-hydroxynaphthalene, arsenocholine, total urinary arsenic, cesium, and tin are positively associated with self-reported emphysema among non-smokers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the NHANES repository provided by the CDC to the public.

References

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (2020) Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2021 report. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GOLD-REPORT-2021-v1.1-25Nov20_WMV.pdf. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

Shapiro SD (2000) Animal models for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 22:4–7

GOLD (2018) Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD, global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD) 2018. https://goldcopd.org/. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ et al (2017) Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195(5):557–582

Mirza S, Clay RD, Koslow MA, Scanlon PD (2018) COPD guidelines: a review of the 2018 GOLD report. Mayo Clin Proc 93(10):1488–1502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.026

Kumar V, Kothiyal NC, Saruchi VP, Sharma R (2016) Sources, distribution, and health effect of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) —current knowledge and future directions. J Chin Adv Mater Soc 4(4):302–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/22243682.2016.1230475

Boström CE, Gerde P, Hanberg A et al (2002) Cancer risk assessment, indicators, and guidelines for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the ambient air. Environ Health Perspect 110(Suppl 3):451–488. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.110-1241197

Shiue I (2016) Urinary polyaromatic hydrocarbons are associated with adult emphysema, chronic bronchitis, asthma, and infections: US NHANES, 2011–2012. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 23(24):25494–25500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-7867-7

Burstyn I, Kromhout H, Partanen T et al (2005) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and fatal ischemic heart disease. Epidemiology 16(6):744–750. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ede.0000181310.65043.2f

Burstyn I, Boffetta P, Heederik D et al (2003) Mortality from obstructive lung diseases and exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons among asphalt workers. Am J Epidemiol 158(5):468–478. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwg180ae

Gammon MD, Sagiv SK, Eng SM et al (2004) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts and breast cancer: a pooled analysis. Arch Environ Health 59(12):640–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/00039890409602948

Zhang Y, Tao S, Shen H, Ma J (2009) Inhalation exposure to ambient polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and lung cancer risk of Chinese population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(50):21063–21067. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0905756106

Ganguly K, Levänen B, Palmberg L, Åkesson A, Lindén A (2018) Cadmium in tobacco smokers: a neglected link to lung disease? Eur Respir Rev 27(147):170122. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0122-2017

Davison AG, Fayers PM, Taylor AJ et al (1988) Cadmium fume inhalation and emphysema. Lancet 1(8587):663–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91474-2

Friberg L (1950) Health hazards in the manufacture of alkaline accumulators with special reference to chronic cadmium poisoning; a clinical and experimental study. Acta Med Scand Suppl 240:1–124

Chung JY, Yu SD, Hong YS (2014) Environmental source of arsenic exposure. J Prev Med Public Health 47(5):253–257. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.14.036

Powers M, Sanchez TR, Grau-Perez M et al (2019) Low-moderate arsenic exposure and respiratory in American Indian communities in the strong heart study. Environ Health 18(1):104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-019-0539-6

Concha G, Broberg K, Grandér M, Cardozo A, Palm B, Vahter M (2010) High-level exposure to lithium, boron, cesium, and arsenic via drinking water in the Andes of northern Argentina. Environ Sci Technol 44(17):6875–6880. https://doi.org/10.1021/es1010384

Svendsen ER, Kolpakov IE, Karmaus WJ et al (2015) Reduced lung function in children associated with cesium 137 body burden. Ann Am Thorac Soc 12(7):1050–1057. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201409-432OC

Rahman HH, Niemann D, Munson-McGee SH (2022) Environmental exposure to metals and the risk of high blood pressure: a cross-sectional study from NHANES 2015–2016. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 29(1):531–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15726-0

Rahman HH, Niemann D, Munson-McGee SH (2021) Association of albumin to creatinine ratio with urinary arsenic and metal exposure: evidence from NHANES 2015–2016 [published online ahed of print, 2021 Oct 13]. Int Urol Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-021-03018-y

Melnikov P, Zanoni LZ (2010) Clinical effects of cesium intake. Biol Trace Elem Res 135(1–3):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-009-8486-7

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (2017) About the national health and nutrition examination jsurvey. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2013) Medical conditions (MCQ_G). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2011-2012/MCQ_G.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2015) Medical conditions (MCQ_H). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2013-2014/MCQ_H.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2017) Medical conditions (MCQ_I). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/MCQ_I.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2013) Metals—urine (UHM_G). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2011-2012/UHM_G.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2016) Metals—urine (UM_H). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2013-2014/UM_H.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2018) Metals—Urine (UM_I). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/UM_I.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2013) Mercury—inorganic, Urine (UHG_G). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2011-2012/UHG_G.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2016) Mercury—urine (UHG_H). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2013-2014/UHG_H.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2018) Mercury—urine (UHG_I). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/UHG_I.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

Akerstrom M, Barregard L, Lundh T, Sallsten G (2013) The relationship between cadmium in kidney and cadmium in urine and blood in an environmentally exposed population. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 268(3):286–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2013.02.009

Jarup L, Berglund M, Elinder CG, Nordberg G, Vahter M (1998) Health effects of cadmium exposure—a review of the literature and a risk estimate. Scand J Work Environ Health 24(Suppl 1):1–51

European Food Safety Authority [EFSA] (2009) Cadmium in food1Scientific opinion of the panel on contaminants in the food chain. EFSA J 980:1–139. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2009.980

Nordberg G, Fowler BA, Nordberg M (2014) Handbook on the toxicology of metals. Academic Press, Cambridge

CDC (2013) Arsenics—total & speciated—urine (UAS_G). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2011-2012/UAS_G.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2016) Arsenic—total—urine (UTAS_H). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2013-2014/UTAS_H.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2016) Arsenics—speciated—urine (UAS_H). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2013-2014/UAS_H.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2018) Arsenic—total—urine (UTAS_I). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/UTAS_I.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2018) Speciated Arsenics - Urine (UAS_I). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/UAS_I.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2014) Polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)—urine (PAH_G). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2011-2012/PAH_G.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2016) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH)—urine (PAH_H). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2013-2014/PAH_H.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2020) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH)—urine (PAH_I). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/PAH_I.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

Shiue I (2015) Urinary heavy metals, phthalates and polyaromatic hydrocarbons independent of health events are associated with adult depression: USA NHANES, 2011–2012. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 22(21):17095–17103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-4944-2

Rahman HH, Niemann D, Munson-McGee SH (2022) Association among urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and depression: a cross-sectional study from NHANES 2015–2016. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 29(9):13089–13097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-16692-3

CDC (2017) Body measures (BMX_I). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/BMX_I.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2017) Demographic Variables and Sample Weights (DEMO_I). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/DEMO_I.htm. Accessed 25 November 2021

CDC (2018) Alcohol use (ALQ_I). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/ALQ_I.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2019) Cotinine and hydroxycotinine—serum (COT_I). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/COT_I.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

CDC (2020) About adult BMI. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html#trends. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

Rahman HH, Niemann D, Singh D (2020) Arsenic exposure and association with hepatitis E IgG antibodies. Occup Dis Environ Med 8:111–122. https://doi.org/10.4236/odem.2020.83009

Rahman HH, Yusuf KK, Niemann D, Dipon SR (2020) Urinary speciated arsenic and depression among US adults. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 27(18):23048–23053. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-08858-2

Rahman HH, Niemann D, Yusuf KK (2022) Association of urinary arsenic and sleep disorder in the US population: NHANES 2015–2016. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 29(4):5496–5504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-16085-6

Rahman HH, Niemann D, Munson-McGee SH (2021) Association of environmental toxic metals with high sensitivity C-reactive protein: a cross-sectional study. Occup Dis Environ Med 9(4):173–184. https://doi.org/10.4236/odem.2021.94013

Tutka P, Mosiewicz J, Wielosz M (2005) Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of nicotine. Pharmacol Rep 57(2):143–153

Fernandes AGO, Santos LN, Pinheiro GP et al (2020) Urinary cotinine as a biomarker of cigarette smoke exposure: a method to differentiate among active, second-hand, and non-smoker circumstances. Open Biomark J 10:60–68. https://doi.org/10.2174/1875318302010010060

CDC (2017) Albumin & creatinine—urine (ALB_CR_I). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/ALB_CR_I.htm. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

R Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Lumley T (2004) Analysis of complex survey samples. J Stat Soft. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v009.i08

Lumley TS (2010) Complex surveys: a guide to analysis using R. Wiley, Hoboken

Lumley T (2020) Package ‘survey’: analysis of complex survey samples, version 4.0. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survey/survey.pdf. Accessed 25 Nov 2021

Susmann H (2016) Package ‘RNHANES’: “facilitates analysis of CDC NHANES,” version 1.1.0. Accessed from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/RNHANES/RNHANES.pdf

CDC (2015) Smoking—cigarette use (SMQ_G). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2011-2012/SMQ_G.htm. Accessed 5 Feb 2022

CDC (2016) Smoking—cigarette use (SMQ_H). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2013-2014/SMQ_H.htm. Accessed 5 Feb 2022

CDC (2017) Smoking—cigarette use (SMQ_I). National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/SMQ_I.htm. Accessed 5 Feb 2022

Wang CK, Lee HL, Chang H, Tsai MH, Kuo YC, Lin P (2012) Enhancement between environmental tobacco smoke and arsenic on emphysema-like lesions in mice. J Hazard Mater 221–222:256–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.04.042

Mazumder DN, Haque R, Ghosh N et al (2000) Arsenic in drinking water and the prevalence of respiratory effects in West Bengal. India Int J Epidemiol 29(6):1047–1052. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/29.6.1047

von Ehrenstein OS, Mazumder DN, Yuan Y et al (2005) Decrements in lung function related to arsenic in drinking water in West Bengal. India Am J Epidemiol 162(6):533–541. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi236

Parvez F, Chen Y, Brandt-Rauf PW et al (2008) Nonmalignant respiratory effects of chronic arsenic exposure from drinking water among never-smokers in Bangladesh. Environ Health Perspect 116(2):190–195. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.9507

Guha Mazumder DN (2007) Arsenic and non-malignant lung disease. J Environ Sci Health A 42(12):1859–1867. https://doi.org/10.1080/10934520701566926

Taylor V, Goodale B, Raab A et al (2017) Human exposure to organic arsenic species from seafood. Sci Total Environ 580:266–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.12.113

Amster ED, Cho JI, Christiani D (2011) Urine arsenic concentration and obstructive pulmonary disease in the U.S. population. J Toxicol Environ Health A 74(11):716–727. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287394.2011.556060

Torén K, Olin AC, Johnsson Å et al (2019) The association between cadmium exposure and chronic airflow limitation and emphysema: the Swedish CArdioPulmonary BioImage Study (SCAPIS pilot). Eur Respir J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00960-2019

Mannino DM, Holguin F, Greves HM, Savage-Brown A, Stock AL, Jones RL (2004) Urinary cadmium levels predict lower lung function in current and former smokers: data from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Thorax 59(3):194–198. https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax.2003.012054

Rokadia HK, Agarwal S (2013) Serum heavy metals and obstructive lung disease: results from the national health and nutrition examination survey. Chest 143(2):388–397. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-0595

Valko M, Rhodes CJ, Moncol J, Izakovic M, Mazur M (2006) Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem Biol Interact 160(1):1–40

Forti E, Bulgheroni A, Cetin Y et al (2010) Characterisation of cadmium chloride induced molecular and functional alterations in airway epithelial cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 25(1):159–168. https://doi.org/10.1159/000272060

Gong Q, Hart BA (1997) Effect of thiols on cadmium-induced expression of metallothionein and other oxidant stress genes in rat lung epithelial cells. Toxicology 119(3):179–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0300-483x(96)03608-

Koizumi S, Gong P, Suzuki K, Murata M (2007) Cadmium-responsive element of the human heme oxygenase-1 gene mediates heat shock factor 1-dependent transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem 282(12):8715–8723. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M609427200

Croute F, Beau B, Arrabit C et al (2000) Pattern of stress protein expression in human lung cell-line A549 after short- or long-term exposure to cadmium. Environ Health Perspect 108(1):55–60. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.0010855

Souza V, Carmen ME, Gómez-Quiroz L et al (2004) Acute cadmium exposure enhances AP-1 DNA binding and induces cytokines expression and heat shock protein 70 in HepG2 cells. Toxicology 197(3):213–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2004.01.006

Almulla AF, Moustafa SR, Al-Dujaili AH, Al-Hakeim HK, Maes M (2021) Lowered serum cesium levels in schizophrenia: association with immune-inflammatory biomarkers and cognitive impairments. Braz J Psychiatry 43(2):131–137. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0908

Vanidassane I, Malik P, Gupta P et al (2021) P54.04 A study to determine the association of trace eelments and heavy metals with lung cancer and their correlation with smoking. J Thorac Oncol 16(3):S531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2021.01.940

Buendia-Roldan I, Palma-Lopez A, Chan-Padilla D et al (2020) Risk factors associated with the detection of pulmonary emphysema in older asymptomatic respiratory subjects. BMC Pulm Med 20(1):164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-020-01204-9

Mamary AJ, Stewart JI, Kinney GL et al (2018) Race and gender disparities are evident in COPD underdiagnoses across all severities of measured airflow obstruction. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis 5(3):177–184. https://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.5.3.2017.0145

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HHR conceptualized the study and contributed to the introduction, discussion and drafting of the paper. SMM conducted the data analysis, methods and contributed to the drafting of the paper. DN contributed to the introduction, discussion and drafting of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable. This study uses only secondary data analyses without any personal information identified using statistical data from the NHANES website, no further ethical approval for conducting the present study is required.

Consent to Participate

Consent was given by all the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rahman, H.H., Niemann, D. & Munson-McGee, S.H. Urinary Metals, Arsenic, and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Exposure and Risk of Self-reported Emphysema in the US Adult Population. Lung 200, 237–249 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-022-00518-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-022-00518-1