Abstract

Introduction

Endoscopic treatment of subglottic stenosis (SGS) is regarded as a safe procedure with rare complications and less morbidity than open surgery yet related with a high risk of recurrence. The abundance of techniques and adjuvant therapies complicates a comparison of the different surgical approaches. The primary aim of this study was to investigate disease recurrence after CO2 laser excisions and balloon dilatation in patients with SGS and to identify potential confounding factors.

Materials and methods

In a tertiary referral center, two cohorts of previously undiagnosed patients treated for SGS were retrospectively reviewed and followed for 3 years. The CO2 laser cohort (CLC) was recruited between 2006 and 2011, and the balloon dilatation cohort (BDC) between 2014 and 2019. Kaplan‒Meier and multivariable Cox regression analyzed time to repeated surgery and estimated hazard ratios (HRs) for different variables.

Results

Nineteen patients were included in the CLC, and 31 in the BDC. The 1-year cumulative recurrence risk was 63.2% for the CLC compared with 12.9% for the BDC (HR 33.0, 95% CI 6.57–166, p < 0.001), and the 3-year recurrence risk was 73.7% for the CLC compared with 51.6% for the BDC (HR 8.02, 95% CI 2.39–26.9, p < 0.001). Recurrence was independently associated with overweight (HR 3.45, 95% CI 1.16–10.19, p = 0.025), obesity (HR 7.11, 95% CI 2.19–23.04, p = 0.001), and younger age at diagnosis (HR 8.18, 95% CI 1.43–46.82, p = 0.018).

Conclusion

CO2 laser treatment is associated with an elevated risk for recurrence of SGS compared with balloon dilatation. Other risk factors include overweight, obesity, and a younger age at diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Subglottic stenosis (SGS) is a rare condition of mucosal scarring, compromising the extrathoracic part of the tracheal airway below the vocal folds. An inflammatory response leading to fibrosis can be triggered by prolonged intubation or tracheostomy, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), or autoimmune conditions, such as vasculitis, sarcoidosis, and relapsing polychondritis [1]. The idiopathic type of SGS is considered to be very rare with an incidence of up to 1:200,000, affecting otherwise healthy perimenopausal females of Caucasian origin [1, 2]. Since SGS presents with common and relatively unspecific symptoms, such as exertional dyspnea, wheezing, chronic cough, or dysphonia, it is frequently misinterpreted as a difficult-to-treat lower airway obstruction resulting in a diagnostic delay of up to 2 years; thus, occasionally manifesting with stridor at rest [3].

Given that recurrence of SGS is regarded as the natural course of the condition, the main treatment goal is to restore durable airway patency without the need for tracheostomy. Open surgical procedures are considered to have the lowest incidence of recurrence; thus, a chance for a permanent treatment. However, these procedures are quite demanding with respect to institutional resources and are associated with increased perioperative and postoperative morbidity in terms of voice and swallowing deterioration [4,5,6]. Endoscopic techniques are low-risk, voice-sparing procedures that are safe to perform in an outpatient surgery setting; thus, have high patient acceptance [7,8,9]. However, they are considered to have a significantly higher recurrence rate than open surgery, reported to be approximately 30% within 1 year postoperatively, 50% within 2 years, and 80% within 3 years [10, 11]. Resection of quadrants of the fibrotic tissue with carbon dioxide (CO2) laser and balloon dilatation alone or following cold knife incisions in the stenotic part of the airway have frequently been used, among others, as the endoscopic treatment of SGS [12]. The rarity of SGS combined with the different types and concepts of endoscopic procedures, the divergence of volumes and resources in different institutions, and other unmeasured confounding factors leading to a selection bias make the comparison of these two techniques complicated [11, 13].

The aim of this study was to describe the disease characteristics of the patient cohort treated for SGS in our institution, a tertiary referral center in Sweden, to retrospectively assess whether balloon dilatation is a superior treatment compared to CO2 laser excision of the scar tissue, and to identify potential confounding factors in terms of time to disease recurrence.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

Previously undiagnosed adult patients treated primarily for isolated SGS at the Örebro University Hospital, a tertiary academic referral center in Sweden, between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2019 were identified based on a retrospective chart review of relevant ICD-10 codes, in particular J38.6, J95.5, and J95.8. Patients with SGS caused by malignant tumors, external compression of the airway, or a damaged laryngotracheal cartilaginous framework, and those previously treated for stenosis in the laryngotracheal part of the airway, or with multilevel and distal tracheal strictures, were excluded from the study.

Surgical techniques

From the early 1990s until 2011, patients with SGS had traditionally been treated with endoscopic CO2 laser excision of the scar tissue by every laryngologist in our institution. The procedure was performed under general anesthesia with high-frequency positive pressure ventilation (HFPPV, Monsoon™ ventilation, Acutronic Medical Systems AG, Fabrik im Schiffli, CH-8816, Hirzel, Switzerland) through a steel, laser-resistant catheter. Stenosis was then either vaporized or divided with radial incisions through suspension microlaryngoscopy, depending on the nature of the cicatrix and its craniocaudal length.

During 2012, Superimposed High-Frequency Jet Ventilation (SHFJV®, Twinstream™, Mariannengasse 17, 1090 Wien, Austria) was introduced at our institution as a promising method for airway surgery. Concurrently, the absence of a ventilation catheter in the trachea favored the switch of our surgical approach from CO2 laser excisions to balloon dilatation of the stenotic part of the airway, which became the surgical method of choice by the end of that year and has exclusively been used since. Through suspension laryngoscopy under general anesthesia with SHJV®, a balloon catheter is advanced in the airway and gently dilates the stenotic part of the airway, following radial incisions with cold steel if appropriate. An INSPIRA AIR® Balloon Dilatation System (Acclarent, Inc., 33 Technology Drive Irvine, CA 92618, USA) sized 14 mm at 10 atm pressure was used until 2017. It was then substituted by Continuous Radial Expansion™ balloons (Boston Scientific Corporation, 300 Boston Scientific Way, Marlborough, MA 01752, USA) for dilations of up to 15 mm at 8 atm pressure in females and 18 mm at 7 atm pressure in males. The pressure was applied during a short period of apnea aiming for a total of three-to-four dilatation attempts, with a duration between 1 and 2 min or until the patient started desaturating, and up to the maximum possible balloon expansion.

Data collection

This sharp switch in the surgical approach of treating SGS in our department generated the two patient groups we utilized in this study: the cohort of patients treated with CO2 laser excisions (CLC) between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2011, and the cohort of patients treated with balloon dilatation (BDC) between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2019. The period from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2013 was considered an adaptation period for both the surgeons and the anesthesiology staff to acquaint themselves with the novel techniques.

The follow-up time for both cohorts was set to 3 years postoperatively. The natural history of the disease after an endoscopic procedure is commonly implicated with a recurrence. In our study, this was defined as significant dyspnea requiring a new surgical treatment when assessed clinically with laryngotracheoscopy by an airway surgeon. Thus, the primary outcome of the study was determined as the time interval from the first surgery until the repeat surgery at recurrence (if it occurred), and the endpoints were a recurrence-free status at 3 years postoperatively or a surgical procedure for recurrence within the follow-up period. Demographic data extracted from the patients’ records included sex, age, time to SGS diagnosis, body mass index (BMI), SGS etiology, smoking history, the presence of diagnosed or self-reported GERD, and tracheal trauma from previous history of tracheostomy at any age or intubation within 2 years prior to the date of diagnosis. Other conditions registered from the patients’ records were diabetes, conditions of the lower airway or the lungs, and cardiovascular comorbidities, including ischemic heart disease, heart failure, arrhythmia, or cerebrovascular condition.

Statistical analysis

A power calculation was made prior to performing the statistical analysis. A total of 72 patients were required to have an 80% chance of detecting a reduction in the recurrence rate from 80% in the CLC group to 50% in the BDC at 3 years postoperatively, which was significant at the 5% level [10, 11]. Continuous variables were analyzed by the Mann‒Whitney U test and are presented as medians and the 25th-to-75th percentiles, whereas categorical variables were analyzed by the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate and are presented as numbers and percentages.

We visualized time to recurrence with the Kaplan‒Meier (KM) method and presented it as cumulative recurrence risk (1-KM). All patients were followed up after the initial operation to the first reoperation or censored at 3 years. Cox proportional hazard models were applied, estimating hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to compare disease recurrence for the two treatment groups. Models were both crude and adjusted for sex, age (categorized as 18–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥ 60 years), cause of SGS, smoking, positive intubation history within 2 years prior to the initial SGS diagnosis, BMI according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification (< 25 kg/m2 defined as normal weight, 25–29.9 kg/m2 defined as overweight, and ≥ 30 kg/m2 defined as obese), presence of self-reported or diagnosed GERD, and diabetes. Confounders were chosen prior to data analysis and in accordance with the previous studies [5, 11, 12]. The proportional hazard assumption was tested by the phtest command in STATA. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. IBM® SPSS® Statistics, version 27 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, USA) and STATA release 17 (StataCorp. 2021. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.) were used for the statistical analysis.

Ethics

This human study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Guidelines and was approved by the Ethics Review Board in Uppsala (diary number 2016/193) and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (diary numbers 2020-05509 and 2022-02708-02). All adult participants provided written informed consent to participate.

Results

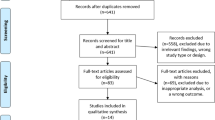

The study population consisted of 19 patients in the CLC and 31 patients in the BDC. We excluded 16 patients in total: Eight of them were previously treated for SGS outside our inclusion period, 3 subjects were found to have multilevel stenosis engaging other parts of the airway (2 with glottic, 1 with bronchial stenosis), 3 cases had a damaged cricotracheal cartilaginous framework and were not appropriate for endoscopic treatment, and in 2 cases treated with CO2 laser, we could not establish contact and receive an informed consent.

Both groups had a similar mean time to diagnosis, yet the mean age at diagnosis was significantly lower in the BLC. The most predominant SGS cause was the idiopathic type, followed by trauma, in both cohorts, and none of the patients were tracheostomized at any age. Table 1 lists the demographic data and comorbidities of the study population at baseline. Only one patient presented with ischemic heart disease. None of them were diagnosed with conditions of the lower airway or the lungs, yet 7 patients had been prescribed steroid inhalers by general practitioners suspecting asthma prior to the diagnosis of SGS. No readmissions or other complications were observed postoperatively for either surgical technique. Because of the relatively small sample size, the SGS cause variable was converted into a binary variable to consolidate the regression analysis.

A total of 30 events were observed in the study population, 14 in the CLC and 16 in the BDC. The 3-year recurrence risk was 73.7% for the CLC (14 of 19 study subjects at risk) compared with 51.6% for the BDC (16 of 31 patients at risk, Fig. 1). As seen in the KM plot, the association between study groups was different during the 3-year follow-up, with a tendency for disease recurrence within the first year in the CLC and after the first year in the BDC. Since the proportional hazard assumption was violated, we modeled the group variable interact with the follow-up time (0–1 vs. 1–3 years) as an indicator variable to estimate time-dependent analysis [14, 15]. In the first year, the cumulative risk of recurrence was 63.2% for the CLC compared to 12.9% for the BDC, with a crude HR of 7.55 (95% CI 2.42–25.6, p < 0.001) and an adjusted HR of 33.0 (95% CI 6.57–166, p < 0.001). Among patients without a recurrence during the first year, the follow-up period from 1 to 3 years showed a crude HR of 0.55 (95% CI 0.12–2.46) and an adjusted HR of 1.85 (95% CI 0.32–10.8).

The adjusted model showed an elevated risk of recurrence in overweight (adjusted HR 3.44, 95% CI 1.16–10.2, p = 0.025) and obese patients (adjusted HR 7.11, 95% CI 2.19–23.0, p = 0.001) compared to normal-weight patients. The group of patients aged 40 years and below was also found to have a higher risk of recurrence (adjusted HR 8.18, 95% CI 1.43–46.8, p = 0.018) than the group of patients aged 50–59 years (Table 2).

Discussion

The primary findings of our study indicate a superiority of balloon dilatation compared to CO2 laser excisions in short-term disease recurrence, particularly within the first year postoperatively. Furthermore, patients who were overweight or obese or had a disease presentation at a younger age were independently found to have a statistically significant increased risk of SGS recurrence.

The diversity of surgical approaches in the endoscopic treatment of SGS, such as different dilation instruments (e.g., rigid endoscopes or inflatable balloons), scar excision instruments (e.g., cold steel or CO2 laser), and adjuvant therapies (e.g., mitomycin C or steroids), complicates the comparison of these procedures. The homogeneity of the two surgical techniques used in our study population facilitates, in essence, the comparison of the thermal effect of a CO2 laser excision with the cold tissue expansion of balloon dilatation, minimizing the confounding impact of different endoscopic treatments. This is reflected by the 51.6% risk of recurrence at 3 years for our BDC group, which is consistent with other studies investigating the outcomes of balloon dilatation without CO2 laser-assisted excisions [5, 6, 13]. There is indisputable evidence that open surgical techniques prevail regarding the durability of maintaining a patent airway without the need for tracheostomy or repeated surgery, eliminating dyspnea. However, they are associated with substantial perioperative risks (e.g., anastomotic complications or temporary tracheostomy). Postoperative morbidity, including poor voice outcomes or even an eventual delayed disease recurrence of up to 30% between 5 and 10 years postoperatively, cannot be overlooked [4, 6, 11, 16,17,18]. Thus, endoscopic treatment still has an important role in the treatment of SGS with its excellent convalescence and despite the higher recurrence rate when compared to open surgical procedures [5, 19].

Our results encourage the use of balloon dilatation instead of CO2 laser excisions considering the longer time to recurrence, since this is ultimately considered the natural course of the condition. We showed that there is a particular propensity for recurrence in the CLC during the first year postoperatively, whereas stenoses treated with balloon dilatation tend to recur during the second year of follow-up. Interestingly, there seems to be a trend of stability in the relapsing manner of the condition in both groups within the third year (73.7% for both the 2-year and 3-year recurrence risk for the CLC compared to 42.9% and 51.6%, respectively, for the BDC; Fig. 1). These findings could be considered in the context of preoperative patient counseling and the individual selection of an endoscopic treatment. The vigilant perspective of an exceptional increase in the incidence of laryngotracheal stenosis during the COVID-19 outbreak [20] led to a prioritized handling of patients with airway problems. Therefore, the treatment of patients with airway obstruction, in particular SGS recurrence, was never delayed.

Although stenoses related to iatrogenic trauma are regarded to be more prevalent [1, 21, 22], the profile of our study population matches the idiopathic type of the condition. Previously published studies have discussed potential environmental or hereditary factors related to the high prevalence of idiopathic SGS [12, 23,24,25,26]. However, this finding might also reflect the anticipative policy in our institution of striving for either tracheostomy in patients with expected prolonged intubation or prompt decannulation combined with noninvasive ventilation to minimize mucosal trauma and scarring predisposing for traumatic SGS. Furthermore, the idiopathic type consists predominantly of otherwise healthy, middle-aged, nonsmoking females experiencing symptoms of dyspnea for approximately 2 years before given the correct diagnosis of SGS [11, 13, 27]. An elevated BMI is also identified as a factor associated with disease recurrence [17, 28, 29]. This view is supported by our findings with a relatively low incidence of comorbidities, and HRs of 3.5 and 7.1 for overweight and obese patients, respectively, compared to normal or underweight patients. The large CIs observed apparently depend on our study’s small sample size.

The theory of a hormonal imbalance in perimenopausal females has been previously studied to explain the onset of idiopathic SGS in that age group. Estrogen receptors are thought to be expressed either unproportionally compared to progesterone receptors and more extensively in females with idiopathic SGS compared to patients with a nonidiopathic type of SGS [30, 31]. Moreover, there is evidence of an age-related elevation in peripheral estrogen formation occurring in adipose tissue [32]. Thus, being overweight or obese could potentially affect and complicate the hormonal equilibrium in premenopausal females contributing to the development of idiopathic SGS before menopause. Pregnancy-associated idiopathic SGS, although a rare entity, further supports the hypothesis of a hormonal origin or blossoming of symptoms in an established and occult stenosis due to the physiological vascular and respiratory changes of pregnancy [33]. These are concepts requiring further studies that could potentially explain the idiopathic prevalence in our cohort and the higher risk of recurrence in the fertile age group (18–39 years old) than in the peri- or postmenopausal age groups.

The major strength of our study is the segmentation of the inclusion period into nonoverlapping timeframes where the physicians in our department performed only one of two interventions, including a distinct learning period in between. In this manner, we sought to minimize performance bias, since nonrandom intervention assignment is a well-described disadvantage in all retrospective studies. Furthermore, only previously untreated patients with isolated stenosis of the subglottic region were included to eliminate the potential confounding effect of scar transformation by previous surgery and potential selection bias. Due to the relapsing nature of SGS and in conformity with results from previous reports [6, 11, 13], the follow-up time was set to 3 years for both cohorts, ensuring an equal and homogenous assessment of the survival analysis.

The absence of an objective and subjective severity grading of stenosis both before the initial intervention and at the clinical assessment upon recurrence is the main limitation of our study. An anatomical classification made by the surgeon was absent from the entire CLC, as neither the Cotton–Myer nor McCaffrey system had been used by the physicians in our department at that time. Although these scales have been widely proposed to assess SGS disease severity and prognosis, the former does not address the length and complexity of the lesion, and the latter does not justify the cross-sectional degree of stenosis [1]. Song et al. [34] showed the poor interrater reliability of a visual estimation in Cotton–Myer grading among physicians and further discussed the difficulty in identifying cricoid cartilage when assessing stenosis length endoscopically. Moreover, neither of the two systems correlates with functional airway assessment with spirometry, as shown by several studies [35,36,37]. Since there is evidence that several measurements of pulmonary function could be used in the diagnosis and postoperative monitoring of patients with SGS [34, 35], the lack of a preoperative functional evaluation with spirometry in our study population is considered another shortcoming of our study. Moreover, it would be interesting to quantify patient-experienced dyspnea using questionnaires specifically developed for upper airway obstruction [38, 39]. However, these data were missing from the entire CLC, since a routine assessment with spirometry and the validated Swedish version of the Dyspnea Index was not introduced as part of the preoperative workup in our department until 2016.

Our study indicates that balloon dilatation is superior to CO2 laser treatment in SGS patients, which is in conformity with several other retrospective studies [5, 6, 13]. Future prospective multicenter randomized control trials are recommended to achieve a sufficient sample size to further evaluate this evidence and examine the effect of adjuvant therapies and the associations of different patient-specific confounders predisposing patients to SGS recurrence.

Conclusion

Endoscopic treatment for SGS with balloon dilatation is more favorable regarding short-term SGS recurrence compared to CO2 laser treatment, and patients with a younger age of SGS onset, overweight, or obesity showed a higher risk for SGS recurrence.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aravena C, Almeida FA, Mukhopadhyay S, Ghosh S, Lorenz RR, Murthy SC et al (2020) Idiopathic subglottic stenosis: a review. J Thorac Dis 12(3):1100–1111

Aarnæs MT, Sandvik L, Brøndbo K (2017) Idiopathic subglottic stenosis: an epidemiological single-center study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 274(5):2225–2228

Gnagi SH, Howard BE, Anderson C, Lott DG (2015) Idiopathic Subglottic and tracheal stenosis: a survey of the patient experience. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 124(9):734–739

Clunie GM, Roe JWG, Alexander C, Sandhu G, McGregor A (2021) Voice and swallowing outcomes following airway reconstruction in adults: a systematic review. Laryngoscope 131(1):146–157

Dwyer CD, Qiabi M, Fortin D, Inculet RI, Nichols AC, MacNeil SD et al (2021) Idiopathic subglottic stenosis: an institutional review of outcomes with a multimodality surgical approach. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 164(5):1068–1076

Gelbard A, Anderson C, Berry LD, Amin MR, Benninger MS, Blumin JH et al (2020) Comparative treatment outcomes for patients with idiopathic subglottic stenosis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146(1):20–29

Naunheim MR, Naunheim ML, Rathi VK, Franco RA, Shrime MG, Song PC (2018) Patient preferences in subglottic stenosis treatment: a discrete choice experiment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 158(3):520–526

Allen CT, Lee CJ, Meyer TK, Hillel AD, Merati AL (2014) Risk stratification in endoscopic airway surgery: is inpatient observation necessary? Am J Otolaryngol 35(6):747–752

Hoffman MR, Brand WT, Dailey SH (2016) Effects of balloon dilation for idiopathic laryngotracheal stenosis on voice production. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 125(1):12–19

Hseu AF, Benninger MS, Haffey TM, Lorenz R (2014) Subglottic stenosis: a ten-year review of treatment outcomes. Laryngoscope 124(3):736–741

Gelbard A, Donovan DT, Ongkasuwan J, Nouraei SA, Sandhu G, Benninger MS et al (2016) Disease homogeneity and treatment heterogeneity in idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope 126(6):1390–1396

Feinstein AJ, Goel A, Raghavan G, Long J, Chhetri DK, Berke GS et al (2017) Endoscopic management of subglottic stenosis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 143(5):500–505

Lavrysen E, Hens G, Delaere P, Meulemans J (2019) Endoscopic treatment of idiopathic subglottic stenosis: a systematic review. Front Surg 6:75

Dekker FW, de Mutsert R, van Dijk PC, Zoccali C, Jager KJ (2008) Survival analysis: time-dependent effects and time-varying risk factors. Kidney Int 74(8):994–997

Jachno KM, Heritier S, Woods RL, Mahady S, Chan A, Tonkin A et al (2022) Examining evidence of time-dependent treatment effects: an illustration using regression methods. Trials 23(1):857

Yamamoto K, Kojima F, Tomiyama KI, Nakamura T, Hayashino Y (2011) Meta-analysis of therapeutic procedures for acquired subglottic stenosis in adults. Ann Thorac Surg 91(6):1747–1753

Carpenter PS, Pierce JL, Smith ME (2018) Outcomes after cricotracheal resection for idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope 128(10):2268–2272

Menapace DC, Modest MC, Ekbom DC, Moore EJ, Edell ES, Kasperbauer JL (2017) Idiopathic subglottic stenosis: long-term outcomes of open surgical techniques. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 156(5):906–911

Richards BA, Xie KZ, Bowen AJ, Aden A, Wiedermann J, Rutt AL et al (2022) Complications following laser wedge excision for idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Am J Otolaryngol 43(6):103629

Piazza C, Filauro M, Dikkers FG, Nouraei SAR, Sandu K, Sittel C et al (2021) Long-term intubation and high rate of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients might determine an unprecedented increase of airway stenoses: a call to action from the European Laryngological Society. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 278(1):1–7

Gelbard A, Francis DO, Sandulache VC, Simmons JC, Donovan DT, Ongkasuwan J (2015) Causes and consequences of adult laryngotracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope 125(5):1137–1143

Fiz I, Monnier P, Koelmel JC, Di Dio D, Fiz F, Missale F et al (2020) Multicentric study applying the european laryngological society classification of benign laryngotracheal stenosis in adults treated by tracheal or cricotracheal resection and anastomosis. Laryngoscope 130(7):1640–1645

Woliansky J, Paddle P, Phyland D (2021) Laryngotracheal stenosis management: a 16-year experience. Ear Nose Throat J 100(5):360–367

Chan RK, Ahrens B, MacEachern P, Bosch JD, Randall DR (2021) Prevalence and incidence of idiopathic subglottic stenosis in southern and central Alberta: a retrospective cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 50(1):64

Anis MM, Zhao Z, Khurana J, Krynetskiy E, Soliman AM (2014) Translational genomics of acquired laryngotracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope 124(5):E175–E179

Drake VE, Gelbard A, Sobriera N, Wohler E, Berry LL, Hussain LL et al (2020) Familial aggregation in idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 163(5):1011–1017

Berges AJ, Lina IA, Chen L, Ospino R, Davis R, Hillel AT (2022) Delayed diagnosis of idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope 132(2):413–418

Menapace DC, Ekbom DC, Larson DP, Lalich IJ, Edell ES, Kasperbauer JL (2019) Evaluating the association of clinical factors with symptomatic recurrence of idiopathic subglottic stenosis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 145(6):524–529

Dang S, Shinn JR, Campbell BR, Garrett G, Wootten C, Gelbard A (2020) The impact of social determinants of health on laryngotracheal stenosis development and outcomes. Laryngoscope 130(4):1000–1006

Fiz I, Bittar Z, Piazza C, Koelmel JC, Gatto F, Ferone D et al (2018) Hormone receptors analysis in idiopathic progressive subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope 128(2):E72–E77

Fiz I, Antonopoulos W, Kölmel JC, Rüller K, Fiz F, Piazza C et al (2022) Hormone pathway comparison in non-idiopathic and idiopathic progressive subglottic stenosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 280:775–780

Nelson LR, Bulun SE (2001) Estrogen production and action. J Am Acad Dermatol 45(3, Supplement):S116–S124

Tapias LF, Rogan TJ, Wright CD, Mathisen DJ (2020) Pregnancy-associated idiopathic laryngotracheal stenosis: presentation, management and results of surgical treatment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 59(1):122–129

Song SA, Santeerapharp A, Choksawad K, Franco RA Jr (2020) Reliability of peak expiratory flow percentage compared to endoscopic grading in subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol 5(6):1133–1139

Ntouniadakis E, Sundh J, von Beckerath M (2022) Monitoring adult subglottic stenosis with spirometry and dyspnea index: a novel approach. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 167(3):517–523

Crosby T, McWhorter A, McDaniel L, Kunduk M, Adkins L (2020) Predicting need for surgery in recurrent laryngotracheal stenosis using changes in spirometry. Laryngoscope 131:2199–2203

Tie K, Buckmire RA, Shah RN (2020) The role of spirometry and dyspnea index in the management of subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope 130(12):2760–2766

Noud M, Hovis K, Gelbard A, Sathe NA, Penson DF, Feurer ID et al (2017) Patient-reported outcome measures in upper airway-related dyspnea: a systematic review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 143(8):824–831

Ntouniadakis E, Brus O, von Beckerath M (2021) Dyspnea Index: An upper airway obstruction instrument; translation and validation in Swedish. Clin Otolaryngol Off J ENT UK Off J Netherlands Soc Otorhinolaryngol Cervicofacial Surg 46(2):380–387

Funding

Open access funding provided by Örebro University. This study was funded by Örebro County Council (ALF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EN: conceptualization, design, conduct, analysis, and writing of the original manuscript draft. JS: design, writing—review and editing, and supervision. AM: analysis, and writing—review and editing. MvonB: design, writing—review and editing, and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ntouniadakis, E., Sundh, J., Magnuson, A. et al. Balloon dilatation is superior to CO2 laser excision in the treatment of subglottic stenosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 280, 3303–3311 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-023-07926-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-023-07926-w