Abstract

Objective

A systematic review and meta-analysis were performed to evaluate the prevalence and prognosis of otorhinolaryngological symptoms in patients with the diagnosed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Methods

A systematic search of PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases was performed up to August 19, 2020.We included studies that reported infections with COVID-19 and symptoms of otolaryngology. The retrieved data from the respective studies were evaluated and summarized. The study's immediate result was to assess the combined prevalence of otorhinolaryngological symptoms in patients with COVID-19. However, the secondary result was to determine the exacerbation of COVID-19 infection in patients with otorhinolaryngological symptoms.

Results

Fifty-four studies with 16,478 patients were included. Olfactory dysfunction, sneezing and sputum production were the 3 most prevalent otorhinolaryngological symptoms in patients with COVID-19. The pooled prevalence amongst the prevalent symptoms was 47% (95% CI 29–65; range 0–98; I2 = 99.58%), 27% (95% CI 11–48; range 12–40; I2 = 93.34%), and 22% (95% CI 16–30; range 2–56; I2 = 97.60%), respectively. The proportion of severely ill patients with sputum production and shortness of breath was significantly higher among patients with COVID-19 infections (OR 1.66 [95% CI 1.08–2.54]; P = 0.02, I2 = 51% and 3.29 [95% CI 1.57–6.90]; P = 0.002, I2 = 49%, respectively). Subgroup analysis showed no statistically significant differences between the incidence of otolaryngology symptoms in severely ill patients and non-severely ill patients (OR 1.43 [95% CI 1.12–1.82]; P = 0.07 I2 = 53.1%). In contrast, the incidence of shortness of breath in severely ill patients was significantly increased (3.29 [1.57–6.90]; P = 0.002, I2 = 49%).

Conclusion

Our research shows that otorhinolaryngology symptoms in patients with COVID-19 are not uncommon, which should attract otorhinolaryngologists' attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

COVID-19 is a new infectious disease caused by a new coronavirus strain (SARS-CoV-2), first reported in Wuhan, China, in 2019 [1]. The disease has a high infection rate with widespread infectivity and has become a global health threat [2]. SARS-CoV-2 is primarily transmitted via the respiratory tract, and the symptoms are similar to that of upper respiratory tract infections, such as fever, dry cough, and fatigue [3]. In severely ill patients, pneumonia manifestations such as dyspnea, imaging abnormalities, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may occur [4]. Moreover, there is evidence that olfactory or taste dysfunction is also one of the early symptoms of COVID-19 [5]. Giacomelli et al. has pointed out that olfactory and taste disorders occur in 34% -59% of COVID-19 patients [6]. Significantly, the British Association of Otorhinolaryngology has proposed olfactory or taste dysfunction as one of the primary screening symptoms of COVID-19 [7]. The discovery has, however, aroused widespread concern among otorhinolaryngologists. Studies have shown that otorhinolaryngological symptoms such as nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and sore throat were also found in COVID-19 patients [8, 9]. The above reports of otorhinolaryngological symptoms are of great significance to diagnosing and treating individual cases, but systematic reviews to summarize the otorhinolaryngological symptoms of COVID-19 patients are scarce.

When patients with upper respiratory symptoms are admitted, otorhinolaryngology and respiratory diseases departments are crucial in treating them. Hence, it is paramount to summarize the otorhinolaryngological characteristics of COVID-19. Thus, the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis study will provide a reference point and better equip otorhinolaryngologists on the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COVID-19 infections.

According to the recently reported studies, the study aims to (i) systematically review and meta-analyze the otorhinolaryngological characteristics of COVID-19 patients, (ii) evaluate the prevalence of otorhinolaryngological symptoms in COVID-19 patients, and (iii) determine if the existence of these symptoms will affect the aggravation of the disease.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

In the present study, we searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Google Scholar data bases from the date of establishment to August 19, 2020, using the keywords "COVID-19" and "Signs and Symptoms." We modified the keywords according to the vocabulary of each database and combined them with the Boolean operators. To retrieve more related papers, we also screened the list of references in the included research.

The literature search was limited to articles published in English. The search strategy was designed by XY, a reviewer with experience in the database search, and later modified by other authors. Endnote (version X9.0) was used to exclude duplicates from the retrieved literature and select qualified studies. All eligible studies reported the otorhinolaryngological symptoms of COVID-19 patients. The following studies were excluded: reviews; editorials; preprint; and small case series (≤ 10 cases).

According to these selection criteria, two reviewers (XY, LL) with experience in systematic reviews independently screened titles and abstracts. When differences exist among reviewers, they are resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer (JQ). Two reviewers (XY, LL) independently rated the included studies' quality using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) quality assessment tool. Differences between the two reviewers were resolved by the third reviewer (JQ).

Data extraction and definitions

Two researchers (XY and LL) who conducted literature retrieval independently extracted data from the included studies. Any differences between the reviewers will be resolved through discussion and consensus or by a third reviewer (JQ). Data extracted from each study included: title; first author; date; study design; country; total sample size; the number of patients with severe and non-severe diseases; otorhinolaryngological symptoms, namely sore throat, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and olfactory dysfunction. The present study followed the PRISMA guidelines on systematic review and meta-analysis based [10].

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

We conducted a meta-analysis on the prevalence rate of otorhinolaryngological symptoms and calculated the combined prevalence rate with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The odds ratio (OR) was used to describe the probability ratio of events in severely and non-severely ill COVID-19 patients. Due to the heterogeneity within and between studies, we use the random effect model to estimate the average effect and its accuracy as it will provide a conservative estimate of 95% CI.

We also conducted a subgroup analysis based on the severity of the disease to observe if the severity of COVID-19 impacted the survey results' estimated prevalence rate. I2 statistic was used to evaluate heterogeneity between studies, and I2 values > 50% indicate significant heterogeneity. Meta-analysis was carried out using the metaprop command in STATA (version 15.0) to merge single-arm ratios. We used Review-Manager (version 5.3) to carry out all other statistical analyses. Funnel charts were used to evaluate publication bias [11].

Results

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 2201 published articles were retrieved from the electronic database (n = 2143) and other sources (n = 58). After removing the duplicates, 1252 published articles were left. After a preliminary review of the title and abstract for each published article, 116 articles were considered to meet the full-text review criteria. After the full-text screening, 54 papers [4, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64], including 16,478 COVID-19 patients, were included in the present systematic review. Figure 1 shows the Prisma flow chart of the research included in the system review.

The main characteristics of the studies and patients included in the meta-analysis are shown in Table 1. All the subjects in the included studies for the present meta-analysis were all adult patients. Based on the included studies, 1523 and 3876 were in severe and non-severe conditions, respectively. All the included studies were published in 2020. The countries included in the study were: 26 studies in China, 8 in the United States, 6 in Italy, and 3 in South Korea. Kuwait, Canada, Bolivia, Germany, France, Brazil, Belgium, Iraq, Iran, Poland, and Switzerland each conducted one study.

Among the studies carried out in China, eleven were from Hubei province, three from Zhejiang province, three from Chongqing city, two from Henan province, and one from Jilin province, Shandong province, Jiangsu province, Taiwan province, Hunan province; and Anhui province. The included reports were all graded as to quality studies according to the NIH quality assessment tool.

Prevalence of otorhinolaryngological symptoms

The present meta-analysis showed that the three most prevalent otorhinolaryngological symptoms among patients with confirmed COVID-19 were olfactory dysfunction, sneezing, and nasal congestion. The pooled prevalence of olfactory dysfunction, from 24 studies (n = 8992), was 47% (95% CI 29–65; range 0–98; I2 = 99.58%). The prevalence of sneezing with COVID-19 infection was reported in three studies. Eighty-nine reported sneezing from a total of 333 patients with a pooled prevalence of 27% (95% CI 11–48; range 12–40; I2 = 93.34%). Among the 24 studies reporting sputum production, the overall prevalence ranged from 2 to 56%. One thousand two hundred and twenty-four of the 6472 patients with COVID-19 infection reported sputum production with a pooled prevalence of 22% (95% CI 16–30; I2 = 97.60%). We also analyzed the prevalence of other otorhinolaryngological symptoms, such as nasal congestion, sore throat, shortness of breath, dizziness, and rhinorrhea. Among them, the pooled prevalence of nasal congestion was 19% (95% CI 11–29; range 0–59; I2 = 98.60%), sore throat 16% (95% CI 12–20; range 1–51; I2 = 95.57%), rhinorrhea 14% (95% CI 9–20; range 0–57; I2 = 97.18%), shortness of breath 12% (95% CI 4–22; range 2–20; I2 = 93.97%), and dizziness 9% (95% CI 4–16; range 2–20; I2 = 93.97%). Figure 2 shows the forest plots for the prevalence of otorhinolaryngological symptoms.

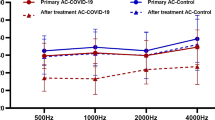

The proportion of severely ill COVID-19 patients with or without otorhinolaryngological symptoms

We analyzed the differences in the proportion of severely ill patients amongst patients with otorhinolaryngological symptoms and those without otorhinolaryngological symptoms. The results are shown in Fig. 3. The proportion of patients with severe COVID-19 was increased in patients with sputum production compared with those without sputum production (OR 1.66 [95% CI 1.08–2.54]; P = 0.02, I2 = 51%).

Similarly, the proportion of severely ill COVID-19 patients with shortness of breath was higher than in patients without shortness of breath (OR 3.29 [95% CI 1.57–6.90]; P = 0.002, I2 = 49%). However, the pooled rate of severity was similar between patients with and without rhinorrhoea (OR 1.02[95% CI 0.68–1.53]; P = 0.93, I2 = 0%). Concerning the analytical results of rhinorrhea, we found out that there was no significant difference in the proportion of severely ill COVID-19 patients with or without nasal congestion (OR 1.39[95% CI 0.74–2.63]; P = 0.31, I2 = 0%), sore throat (OR 1.10[95% CI 0.79–1.54]; P = 0.56, I2 = 16%), or dizziness (OR 1.17[95% CI 0.59–2.34]; P = 0.65, I2 = 0%).

The differences in otorhinolaryngological symptoms between severe and non-severely ill patients

We analyzed the differences in otorhinolaryngological symptoms between severe and non-severely COVID-19 patients (Fig. 4). Patients with severe disease were similar to have otorhinolaryngological symptoms compared with those with non-severe disease (OR 1.43 [95% CI 1.12–1.82]; P = 0.07 I2 = 53.1%). Correspondingly, we found no significant difference between severely and non-severely ill patients with sputum production (1.52 [0.99–2.33]; P = 0.05; I2 = 49%), sore throat (1.15[0.84–1.58]; P = 0.39; I2 = 13%), rhinorrhea (1.02 [0.68–1.53]; P = 0.93; I2 = 0), or nasal congestion (1.28 [0.62–2.67]; P = 0.51, I2 = 5%). However, severely ill patients were more likely to have shortness of breath than non-severely ill patients with the disease (3.29 [1.57–6.90]; P = 0.002, I2 = 49%).

Discussion

Several studies have reported on the otorhinolaryngological symptoms of COVID-19 patients. The present study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of otorhinolaryngological symptoms in COVID-19 patients. Significantly, otorhinolaryngological symptoms are not uncommon in patients with COVID-19, for which the incidence of olfactory dysfunction, sneezing, sputum production, nasal congestion and sore throat exceeds 15%. With the increase in the severity of the disease, shortness of breath becomes more apparent. Patients with sputum production or shortness of breath have an increased risk of developing associated complications, severely impacting patients' prognosis.

The study results show that the incidence of otorhinolaryngological symptoms in COVID-19 is 47% for olfactory dysfunction, 27% for sneezing, 22% for sputum production, 19% for nasal congestion, 16% for sore throat, 14% for rhinorrhea, 12% for shortness of breath, and 9% for dizziness. Although the occurrence of otorhinolaryngological symptoms is less threatening to patients' lives, its incidence has nonetheless exceeded that of digestive system symptoms such as diarrhea and nausea [65].

Olfactory dysfunction is the otorhinolaryngological symptom with the highest incidence in the study, and it is also a recognized WHO sign for COVID-19 infection [39]. Initially, a few scholars have conducted a separate systematic evaluation of the incidence of olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients. In a study by Agyeman et al., the incidence of olfactory dysfunction was 41% [66], while in another study by Gramel Tong et al. was 52.73% [67]. The present study results show that olfactory dysfunction is 47%, which is similar to the results of the previous two studies.

The cause of olfactory dysfunction caused by SARS-CoV-2 is not completely clear. A previous study has proposed that SARS-CoV-2 can enter epithelial cells by directly binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the cell surface. Simultaneously, ACE2 is highly expressed in the nasal mucosal epithelium, especially in ciliated epithelium and goblet cells, which may be one reason for SARS-CoV-2's olfactory dysfunction [68]. Also, the theory that the upper respiratory tract virus destroys olfactory nerve epithelium and leads to chronic olfactory dysfunction has been reported in previous literature [69].

An expert who carried out animal experiments has confirmed that coronavirus is highly neurotropic and can directly affect olfactory neurons, which might be another fundamental cause of olfactory dysfunctions induced by the novel coronavirus [70]. When the potential target of SARS-CoV-2 is located in non-neuro-olfactory epithelial cells, the patient's olfactory function often recovers within 2 to 4 weeks [71]. Significantly, once the virus infects olfactory stem cells, such as horizontal basal cells, it can cause long-term olfactory dysfunctions [72]. Notably, Kaye et al. pointed out that olfactory dysfunction as the first symptom appeared in 26.6% of COVID-19 patients [73].

Hence, it is of the utmost importance for otorhinolaryngologists to be well equipped in the vast symptoms of COVID-19 to avoid missed diagnosis. Simultaneously, timely treatment should be given after the diagnosis of COVID-19 to prevent long-term olfactory dysfunction. Nasopharyngeal swabs and oropharyngeal swabs are the primary sites for collecting upper respiratory tract samples because the nasopharynx or oropharynx is the central location of COVID-19 infection and the primary source of transmission of the infection [2]. SARS-CoV-2 damage to the nasopharynx is the leading cause of nasopharyngeal symptoms. In the present study, the incidence of sneezing and sputum production was > 15%, and the emergence of both symptoms was also the primary way of COVID-19's transmission. Thus, otolaryngologists should take necessary protective measures while improving the current diagnostic criteria.

We further investigated the effects of different otorhinolaryngological symptoms on the various causes of COVID-19. We found that severe illness incidence in patients with sputum production or shortness of breath was significantly higher than patients without sputum production or shortness of breath. The occurrence of symptoms such as nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, sore throat, or vertigo had no significant effect on the incidence of COVID-19. Li et al. pointed out that sputum production is one of the signs of severe COVID-19 infection, while shortness of breath was a common symptom of critically ill COVID-19 patients [34]. Therefore, we believe that the occurrence of sputum production or shortness of breath has a particular value in predicting the severity of the disease. The emergence of these symptoms should attract otorhinolaryngologists' intense attention, and timely control should be carried out at the early onset of symptoms to prevent the disease from progressing to a severe stage with adverse effects on patient's lives.

We analyzed the incidence of various otorhinolaryngological symptoms in severely and non-severely ill patients to understand further the relationship between otorhinolaryngological symptoms and the severity of COVID-19. We found out that the prevalence rate of shortness of breath in severely ill COVID-19 patients was significantly higher than non-severely ill patients. The results were also in line with previously published studies [4, 34]. Therefore, one can consider the shortness of breath as a sign of intensive care for confirmed cases. However, when various symptoms such as sputum production, sore throat, nasal congestion, and rhinorrhea were considered, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of otorhinolaryngological symptoms between severely ill patients and non-severely ill patients.Wei et al. analyzed the data of 276 patients in Hubei Province and found no significant difference in the incidence of sputum production and sore throat between severely ill patients and non-severely ill patients [49]. The study of Wang et al. also provided support for the present study analysis. After following up on the patients' progress in the square cabin hospital, there were no significant differences in nasal congestion and rhinorrhea between the aggravated patients and the non-aggravated patients [47].The above results show that most otorhinolaryngological symptoms are common in severely ill and non-severely ill patients. Otorhinolaryngologists should maintain a high degree of clinical suspicion during the epidemic and implement active protection strategies to prevent the widespread nosocomial infection caused by negligence in diagnosis.

In conclusion, the study results show that the otorhinolaryngological symptoms of COVID-19 patients are not uncommon. Otorhinolaryngologists should improve their understanding of otorhinolaryngology symptoms in COVID-19 patients and pay keen attention to their differentiation. Simultaneously, otorhinolaryngologists should pay special attention to the symptoms of shortness of breath and sputum production in COVID-19 patients to prevent aggravating the disease and causing irreversible damage to patients.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are in this published article.

References

Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS (2020) Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 382(18):1708–1720. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

Pascarella G, Strumia A, Piliego C, Bruno F, Del Buono R, Costa F, Scarlata S, Agrò FE (2020) COVID-19 diagnosis and management: a comprehensive review. J Intern Med 288(2):192–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13091

Wu D, Wu T, Liu Q, Yang Z (2020) The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: what we know. Int J Infect Dis 94:44–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.004

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet (London, England) 395(10223):497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5

Xydakis MS, Dehgani-Mobaraki P, Holbrook EH, Geisthoff UW, Bauer C, Hautefort C, Herman P, Manley GT, Lyon DM, Hopkins C (2020) Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis 20(9):1015–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30293-0

Giacomelli A, Pezzati L, Conti F, Bernacchia D, Siano M, Oreni L, Rusconi S, Gervasoni C, Ridolfo AL, Rizzardini G, Antinori S, Galli M (2020) Self-reported olfactory and taste disorders in patients with severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 infection: a cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis 71(15):889–890. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa330

Coleman JJ, Manavi K, Marson EJ, Botkai AH, Sapey E (2020) COVID-19: to be or not to be; that is the diagnostic question. Postgrad Med J 96(1137):392–398. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137979

Lovato A, de Filippis C, Marioni G (2020) Upper airway symptoms in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Am J Otolaryngol 41(3):102474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102474

Lovato A, de Filippis C (2020) Clinical presentation of COVID-19: a systematic review focusing on upper airway symptoms. Ear Nose Throat J 99(9):569–576. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145561320920762

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 315(7109):629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

Aggarwal S, Garcia-Telles N, Aggarwal G, Lavie C, Lippi G, Henry BM (2020) Clinical features, laboratory characteristics, and outcomes of patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): early report from the United States. Diagnosis (Berlin, Germany) 7(2):91–96. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2020-0046

Andrikopoulou M, Madden N, Wen T, Aubey JJ, Aziz A, Baptiste CD, Breslin N, DʼAlton ME, Fuchs KM, Goffman D, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Matseoane-Peterssen DN, Miller RS, Sheen JJ, Simpson LL, Sutton D, Zork N, Friedman AM, (2020) Symptoms and critical illness among obstetric patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Obstet Gynecol 136(2):291–299. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000003996

Argenziano MG, Bruce SL, Slater CL, Tiao JR, Baldwin MR, Barr RG, Chang BP, Chau KH, Choi JJ, Gavin N, Goyal P, Mills AM, Patel AA, Romney MS, Safford MM, Schluger NW, Sengupta S, Sobieszczyk ME, Zucker JE, Asadourian PA, Bell FM, Boyd R, Cohen MF, Colquhoun MI, Colville LA, de Jonge JH, Dershowitz LB, Dey SA, Eiseman KA, Girvin ZP, Goni DT, Harb AA, Herzik N, Householder S, Karaaslan LE, Lee H, Lieberman E, Ling A, Lu R, Shou AY, Sisti AC, Snow ZE, Sperring CP, Xiong Y, Zhou HW, Natarajan K, Hripcsak G, Chen R (2020) Characterization and clinical course of 1000 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York: retrospective case series. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 369:m1996. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1996

Boscolo-Rizzo P, Borsetto D, Spinato G, Fabbris C, Menegaldo A, Gaudioso P, Nicolai P, Tirelli G, Da Mosto MC, Rigoli R, Polesel J, Hopkins C (2020) New onset of loss of smell or taste in household contacts of home-isolated SARS-CoV-2-positive subjects. Eur Arch Oto-rhino-laryngol 277(9):2637–2640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06066-9

Burke RM, Killerby ME, Newton S, Ashworth CE, Berns AL, Brennan S, Bressler JM, Bye E, Crawford R, Harduar Morano L, Lewis NM, Markus TM, Read JS, Rissman T, Taylor J, Tate JE, Midgley CM (2020) Symptom profiles of a convenience sample of patients with COVID-19 - United States, January-April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69(28):904–908. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6928a2

Carignan A, Valiquette L, Grenier C, Musonera JB, Nkengurutse D, Marcil-Héguy A, Vettese K, Marcoux D, Valiquette C, Xiong WT, Fortier PH, Généreux M, Pépin J (2020) Anosmia and dysgeusia associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: an age-matched case-control study. Can Med Assoc J 192(26):702. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200869

Cecconi M, Piovani D, Brunetta E, Aghemo A, Greco M, Ciccarelli M, Angelini C, Voza A, Omodei P, Vespa E, Pugliese N, Parigi TL, Folci M, Danese S, Bonovas S (2020) Early Predictors of Clinical Deterioration in a Cohort of 239 Patients Hospitalized for Covid-19 Infection in Lombardy Italy. J Clin Med 9:5. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051548

Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia J, Yu T, Zhang X, Zhang L (2020) Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet (London, England) 395(10223):507–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30211-7

Dell’Era V, Farri F, Garzaro G, Gatto M, Aluffi Valletti P, Garzaro M (2020) Smell and taste disorders during COVID-19 outbreak: Cross-sectional study on 355 patients. Head Neck 42(7):1591–1596. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26288

Du N, Chen H, Zhang Q, Che L, Lou L, Li X, Zhang K, Bao W (2020) A case series describing the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 infection in Jilin Province. Virulence 11(1):482–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2020.1767357

Du W, Yu J, Wang H, Zhang X, Zhang S, Li Q, Zhang Z (2020) Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in children compared with adults in Shandong Province China. Infection 48(3):445–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-020-01427-2

Duan X, Guo X, Qiang J (2020) A retrospective study of the initial 25 COVID-19 patients in Luoyang China. Jap J Radiol 38(7):683–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-020-00988-4

Duanmu Y, Brown IP, Gibb WR, Singh J, Matheson LW, Blomkalns AL, Govindarajan P (2020) Characteristics of Emergency Department Patients With COVID-19 at a Single Site in Northern California: Clinical Observations and Public Health Implications. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med 27(6):505–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14003

Escalera-Antezana JP, Lizon-Ferrufino NF, Maldonado-Alanoca A, Alarcón-De-la-Vega G, Alvarado-Arnez LE, Balderrama-Saavedra MA, Bonilla-Aldana DK, Rodríguez-Morales AJ (2020) Clinical features of the first cases and a cluster of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Bolivia imported from Italy and Spain. Travel Med Infect Dis 35:101653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101653

Haehner A, Draf J, Dräger S, de With K, Hummel T (2020) Predictive value of sudden olfactory loss in the diagnosis of COVID-19. ORL 82(4):175–180. https://doi.org/10.1159/000509143

Huang R, Zhu L, Xue L, Liu L, Yan X, Wang J, Zhang B, Xu T, Ji F, Zhao Y, Cheng J, Wang Y, Shao H, Hong S, Cao Q, Li C, Zhao XA, Zou L, Sang D, Zhao H, Guan X, Chen X, Shan C, Xia J, Chen Y, Yan X, Wei J, Zhu C, Wu C (2020) Clinical findings of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Jiangsu province, China: a retrospective, multi-center study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14(5):e0008280. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008280

Kim ES, Chin BS, Kang CK, Kim NJ, Kang YM, Choi JP, Oh DH, Kim JH, Koh B, Kim SE, Yun NR, Lee JH, Kim JY, Kim Y, Bang JH, Song KH, Kim HB, Chung KH, Oh MD (2020) Clinical Course and Outcomes of Patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection: a Preliminary Report of the First 28 Patients from the Korean Cohort Study on COVID-19. J Korean Med Sci 35(13):e142. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e142

Kim GU, Kim MJ, Ra SH, Lee J, Bae S, Jung J, Kim SH (2020) Clinical characteristics of asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with mild COVID-19. Clin Microbiol 26(7):948.e941-948.e943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.040

Klopfenstein T, Kadiane-Oussou NJ, Toko L, Royer PY, Lepiller Q, Gendrin V, Zayet S (2020) Features of anosmia in COVID-19. Medecine et maladies infectieuses 50(5):436–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2020.04.006

Kosugi EM, Lavinsky J, Romano FR, Fornazieri MA, Luz-Matsumoto GR, Lessa MM, Piltcher OB, Sant’Anna GD (2020) Incomplete and late recovery of sudden olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 86(4):490–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2020.05.001

Lechien JR, Cabaraux P, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Khalife M, Hans S, Calvo-Henriquez C, Martiny D, Journe F, Sowerby L, Saussez S (2020) Objective olfactory evaluation of self-reported loss of smell in a case series of 86 COVID-19 patients. Head Neck 42(7):1583–1590. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26279

Lee Y, Min P, Lee S, Kim SW (2020) Prevalence and duration of acute loss of smell or taste in COVID-19 patients. J Korean Med Sci 35(18):e174. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e174

Li J, Chen Z, Nie Y, Ma Y, Guo Q, Dai X (2020) Identification of symptoms prognostic of COVID-19 severity: multivariate data analysis of a case series in Henan Province. J Med Internet Res 22(6):e19636. https://doi.org/10.2196/19636

Li K, Wu J, Wu F, Guo D, Chen L, Fang Z, Li C (2020) The clinical and chest CT features associated with severe and critical covid-19 pneumonia. Invest Radiol 55(6):327–331. https://doi.org/10.1097/rli.0000000000000672

Liu JY, Chen TJ, Hwang SJ (2020) Analysis of imported cases of COVID-19 in Taiwan: a nationwide study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093311

Liu K, Fang YY, Deng Y, Liu W, Wang MF, Ma JP, Xiao W, Wang YN, Zhong MH, Li CH, Li GC, Liu HG (2020) Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J 133(9):1025–1031. https://doi.org/10.1097/cm9.0000000000000744

Merza MA, Haleem Al Mezori AA, Mohammed HM, Abdulah DM (2020) COVID-19 outbreak in Iraqi Kurdistan: The first report characterizing epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological findings of the disease. Diabetes Metab Syndr 14(4):547–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.047

Moein ST, Hashemian SM, Mansourafshar B, Khorram-Tousi A, Tabarsi P, Doty RL (2020) Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID-19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 10(8):944–950. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22587

Sierpiński R, Pinkas J, Jankowski M, Zgliczyński WS, Wierzba W, Gujski M, Szumowski Ł (2020) Sex differences in the frequency of gastrointestinal symptoms and olfactory or taste disorders in 1942 nonhospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Polish Arch Int Med 130(6):501–505. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.15414

Speth MM, Singer-Cornelius T, Oberle M, Gengler I, Brockmeier SJ, Sedaghat AR (2020) Olfactory dysfunction and sinonasal symptomatology in COVID-19: prevalence, severity, timing, and associated characteristics. Otolaryngol -Head Neck Surg. 163(1):114–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820929185

Vaira LA, Deiana G, Fois AG, Pirina P, Madeddu G, De Vito A, Babudieri S, Petrocelli M, Serra A, Bussu F, Ligas E, Salzano G, De Riu G (2020) Objective evaluation of anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 patients: Single-center experience on 72 cases. Head Neck 42(6):1252–1258. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26204

Vaira LA, Hopkins C, Petrocelli M, Lechien JR, Soma D, Giovanditto F, Rizzo D, Salzano G, Piombino P, Saussez S, de Riu G (2020) Do olfactory and gustatory psychophysical scores have prognostic value in COVID-19 patients? A prospective study of 106 patients. J Otolaryngol 49(1):56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-020-00449-y

Vaira LA, Hopkins C, Salzano G, Petrocelli M, Melis A, Cucurullo M, Ferrari M, Gagliardini L, Pipolo C, Deiana G, Fiore V, De Vito A, Turra N, Canu S, Maglio A, Serra A, Bussu F, Madeddu G, Babudieri S, Giuseppe Fois A, Pirina P, Salzano FA, De Riu P, Biglioli F, De Riu G (2020) Olfactory and gustatory function impairment in COVID-19 patients: Italian objective multicenter-study. Head Neck 42(7):1560–1569. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26269

Wan S, Xiang Y, Fang W, Zheng Y, Li B, Hu Y, Lang C, Huang D, Sun Q, Xiong Y, Huang X, Lv J, Luo Y, Shen L, Yang H, Huang G, Yang R (2020) Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in northeast Chongqing. J Med Virol 92(7):797–806. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25783

Wang D, Yin Y, Hu C, Liu X, Zhang X, Zhou S, Jian M, Xu H, Prowle J, Hu B, Li Y, Peng Z (2020) Clinical course and outcome of 107 patients infected with the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, discharged from two hospitals in Wuhan, China. Crit Care (London, England) 24(1):188. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-02895-6

Wang X, Fang J, Zhu Y, Chen L, Ding F, Zhou R, Ge L, Wang F, Chen Q, Zhang Y, Zhao Q (2020) Clinical characteristics of non-critically ill patients with novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in a Fangcang Hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect 26(8):1063–1068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.032

Wang Z, Yang B, Li Q, Wen L, Zhang R (2020) Clinical features of 69 cases with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 71(15):769–777. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa272

Wei Y, Zeng W, Huang X, Li J, Qiu X, Li H, Liu D, He Z, Yao W, Huang P, Li C, Zhu M, Zhong C, Zhu X, Liu J (2020) Clinical characteristics of 276 hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Zengdu District, Hubei Province: a single-center descriptive study. BMC Infect Dis 20(1):549. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05252-8

Wu J, Liu J, Zhao X, Liu C, Wang W, Wang D, Xu W, Zhang C, Yu J, Jiang B, Cao H, Li L (2020) Clinical characteristics of imported cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Jiangsu Province: a multicenter descriptive study. Clin Infect Dis 71(15):706–712. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa199

Wu J, Wu X, Zeng W, Guo D, Fang Z, Chen L, Huang H, Li C (2020) Chest CT findings in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and its relationship with clinical features. Invest Radiol 55(5):257–261. https://doi.org/10.1097/rli.0000000000000670

Xu XW, Wu XX, Jiang XG, Xu KJ, Ying LJ, Ma CL, Li SB, Wang HY, Zhang S, Gao HN, Sheng JF, Cai HL, Qiu YQ, Li LJ (2020) Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 368:m606. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m606

Yan CH, Faraji F, Prajapati DP, Boone CE, DeConde AS (2020) Association of chemosensory dysfunction and COVID-19 in patients presenting with influenza-like symptoms. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 10(7):806–813. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22579

Yan CH, Faraji F, Prajapati DP, Ostrander BT, DeConde AS (2020) Self-reported olfactory loss associates with outpatient clinical course in COVID-19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 10(7):821–831. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22592

Yan N, Wang W, Gao Y, Zhou J, Ye J, Xu Z, Cao J, Zhang J (2020) Medium term follow-up of 337 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a Fangcang Shelter Hospital in Wuhan China. Front Med 7:373. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.00373

Yang BY, Barnard LM, Emert JM, Drucker C, Schwarcz L, Counts CR, Murphy DL, Guan S, Kume K, Rodriquez K, Jacinto T, May S, Sayre MR, Rea T (2020) clinical characteristics of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) receiving emergency medical services in king county Washington. JAMA Netw Open 3(7):e2014549. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14549

Yang W, Cao Q, Qin L, Wang X, Cheng Z, Pan A, Dai J, Sun Q, Zhao F, Qu J, Yan F (2020) Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multi-center study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang China. J Infect 80(4):388–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.016

Yin S, Peng Y, Ren Y, Hu M, Tang L, Xiang Z, Li X, Wang M, Wang W (2020) The implications of preliminary screening and diagnosis: Clinical characteristics of 33 mild patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Hunan, China. J Clin Virol 128:104397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104397

Yu C, Lei Q, Li W, Wang X, Li W, Liu W (2020) Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 1663 hospitalized patients infected with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a single-center experience. J Infect Public Health 13(9):1202–1209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.07.002

Zhang X, Cai H, Hu J, Lian J, Gu J, Zhang S, Ye C, Lu Y, Jin C, Yu G, Jia H, Zhang Y, Sheng J, Li L, Yang Y (2020) Epidemiological, clinical characteristics of cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection with abnormal imaging findings. Int J Infect Dis 94:81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.040

Zhao D, Yao F, Wang L, Zheng L, Gao Y, Ye J, Guo F, Zhao H, Gao R (2020) A comparative study on the clinical features of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia with other pneumonias. Clin Infect Dis 71(15):756–761. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa247

Zhao XY, Xu XX, Yin HS, Hu QM, Xiong T, Tang YY, Yang AY, Yu BP, Huang ZP (2020) Clinical characteristics of patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in a non-Wuhan area of Hubei Province, China: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 20(1):311. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05010-w

Zheng Y, Xiong C, Liu Y, Qian X, Tang Y, Liu L, Leung EL, Wang M (2020) Epidemiological and clinical characteristics analysis of COVID-19 in the surrounding areas of Wuhan, Hubei Province in 2020. Pharmacol Res 157:104821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104821

Almazeedi S, Al-Youha S, Jamal MH, Al-Haddad M, Al-Muhaini A, Al-Ghimlas F, Al-Sabah S (2020) Characteristics, risk factors and outcomes among the first consecutive 1096 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in Kuwait. EClinicalMedicine 24:100448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100448

Zarifian A, Zamiri Bidary M, Arekhi S, Rafiee M, Gholamalizadeh H, Amiriani A, Ghaderi MS, Khadem-Rezaiyan M, Amini M, Ganji A (2020) Gastrointestinal and hepatic abnormalities in patients with confirmed COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26314

Agyeman AA, Chin KL, Landersdorfer CB, Liew D, Ofori-Asenso R (2020) Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc 95(8):1621–1631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.030

Tong JY, Wong A, Zhu D, Fastenberg JH, Tham T (2020) The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 163(1):3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820926473

Sungnak W, Huang N, Bécavin C, Berg M, Queen R, Litvinukova M, Talavera-López C, Maatz H, Reichart D, Sampaziotis F, Worlock KB, Yoshida M, Barnes JL (2020) SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med 26(5):681–687. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0868-6

Doty RL (2008) The olfactory vector hypothesis of neurodegenerative disease: is it viable? Ann Neurol 63(1):7–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.21327

Wheeler DL, Athmer J, Meyerholz DK, Perlman S (2017) Murine olfactory bulb interneurons survive infection with a neurotropic coronavirus. J Virol 91:22. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01099-17

Jain A, Kumar L, Kaur J, Baisla T, Goyal P, Pandey AK, Das A, Parashar L (2020) Olfactory and taste dysfunction in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: its prevalence and outcomes. J Laryngol Otol. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022215120002467

Schwob JE (2002) Neural regeneration and the peripheral olfactory system. Anat Rec 269(1):33–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.10047

Kaye R, Chang CWD, Kazahaya K, Brereton J, Denneny JC (2020) COVID-19 anosmia reporting tool: initial findings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 163(1):132–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820922992

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JQ, XY, and LL: designed the study, performed the systematic literature search, review, data extraction, statistical data analysis and interpretation, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JQ and TW: verified data extraction, data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. XY and LC: critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. YM and YS: supervised the data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and wrote the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest in this study.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, J., Yang, X., Liu, L. et al. Prevalence and prognosis of otorhinolaryngological symptoms in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 279, 49–60 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-021-06900-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-021-06900-8