Abstract

Purpose

Adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands is of low incidence and a broad range of histopathological subtypes. Cancer stem cell markers (CSC) might serve as novel prognostic parameters. To date, only a few studies examined the expression of CSC in adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands with diverging results. To further investigate the reliability in terms of prognostic value, a histopathological analysis of CSCs on a cohort of patients with adenocarcinomas of the major salivary glands was performed.

Methods

Tumor samples of 40 consecutive patients with adenocarcinoma of the major salivary gland treated with curative intend at one tertiary center were stained with the CSCs ALDH1, BMI-1, CD44, Nanog, and SOX2. Expression of these markers was correlated with clinicopathological parameters and survival estimates.

Results

Correlation of high expression of ALDH1 with higher grading (p < 0.001) and high expression of CD44 with the localization of the neoplasm (p = 0.05), larger tumor size (p = 0.006), positive pN-category (p = 0.023), and advanced UICC stage (p = 0.002) was found. Furthermore, high expression of SOX2 correlated with a negative perineural invasion (p = 0.02). No significant correlation of any investigated marker with survival estimates was observed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study did not find a significant correlation of the investigated CSCs with survival estimates in adenocarcinoma of the major salivary glands. Recapitulating the results of our study in conjunction with data in the literature, the CSCs ALDH1, BMI-1, CD44, Nanog, and SOX2 do not seem to serve as reliable prognostic parameters in the treatment of adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Malignoma of the salivary glands exhibits a low incidence of 2.5–3.0 cases per 100,000 people per year [1]. Together with a broad range of more than 20 histological subtypes, and different localization, the investigation of this disease seems challenging [2]. However, a multimodal treatment-regimen with radical resection of the tumour, neck dissection, and adjuvant radiotherapy is recommended, and has shown superior survival in comparison to resection alone [3]. Clinical parameters like histopathological entity, grading, tumour size, and perineural invasion have proven helpful to estimate prognosis in malignoma of the salivary glands [4]. In cases of recurrence or inoperability, treatment options are limited and mostly chemotherapy in terms of a palliative care setting remain [5]. With a disease so rare combined with a possibly poor prognosis, further investigations about the pathogenesis of those tumour entities is required to improve treatment concepts.

Cancer stem cells are known to exhibit infinite properties of self-renewal, reconstitution of tumour-heterogeneity and maintenance of tumour growth [6]. Since the discovery of cancer stem cells, the involvement of certain markers as key regulators in oncologic diseases has been investigated thoroughly throughout the past decades [7]. In the head and neck region, cancer stem cell markers (CSC) are suspected to play a role in oncogenesis, as well as progression and prognosis of the disease [8]. ALDH1 serves as a marker for both tissue-resident stem cells, as well as cancer stem cells of different tissue types [9], like lung, colon, prostate, pancreatic, endometroid cancer, and head and neck malignoma [10]. BMI-1 is an epigenetic key regulator and influences p53 and Rb proteins, and was found to function as an enhancer for self-renewal in hematopoietic stem cells [11], head and neck tumours, and breast adenocarcinomas [12]. CD44 is known as a pivotal marker for cancer stem cells, and an overexpression in cancer cells with a suspected exhibition of highly malignant and therapeutic resistance properties is reported [13]. Also, a correlation of CD44 overexpression in head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC) was observed [14]. The cancer stem cell marker Nanog serves as a marker for pluripotency in both tissue-resident and cancer stem cells and plays a role in maintaining pluripotency [15]. Nanog is reported to correlate with a promotion of metastasis and poor prognosis in HNSCC [16]. SOX2, together with Nanog, is a transcription factor associated with the maintenance of stem cell pluripotency [17]. A correlation with an aggressive feature is reported in colon cancer, breast cancer, and HNSCC [18].

Evaluation of expression of those markers in malignoma of the salivary glands exists only in a few studies so far, which have shown diverging results in correlation with clinicopathological parameters and survival estimates. Thus, the question arises how reliable those CSCs could be in terms of a prognostic parameter. Therefore, we performed a histopathological analysis on a cohort of patients with adenocarcinomas of the major salivary glands to gain further insights into the promising novel prognostic parameter.

Material and methods

Patients and compliance with ethical standards

Retrospective analysis of 132 consecutive patients treated for epithelial malignoma of the salivary glands at one tertiary referral centre, the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, University Medical Centre Göttingen, Georg-August University Göttingen, Germany from 2003 to 2015. Patients treated primarily by surgery in curative intent, and in which an adenocarcinoma of the parotid or submandibular gland was diagnosed pathologically, were included in the analysis (Fig. 1a). 40 patients fulfilled those criteria. The analysis included patients’ and disease characteristics, as well as survival-rates.

Inclusion criteria and subtypes of adenocarcinomas. a 40 patients with adenocarcinoma of the major salivary glands, who received surgical treatment at one tertiary centre were included in the study. b 9 different entities of adenocarcinoma were summarized as adenocarcinoma of the major salivary glands, listed in a descending order regarding their share of patients (%). AC, adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell cancer

The study protocol was performed according to the ethical guidelines of the 2002 Declaration of Helsinki and carried out after approval by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the University Medical Centre Göttingen (reference number 2/1/17). All patients gave written consent to the study.

Immunohistochemistry

After assembly of 40 haematoxylin and eosin-stained slides into a tissue-microarray paraffin block, one-millimetre thick sections were cut and immunohistochemically (IHC) stained. Sections were dewaxed with clearify clearing agent (Agilent, Hamburg, Germany) for 20 min at 65 °C and blocked with EnV FLEX Peroxidase-Blocking Reagent (Agilent, Hamburg, Germany) for 15 min at 97 °C. IHC staining for ALDH-1 (1:200 FLEX + Rabbit, ABCAM, Cambridge, United Kingdom), BMI-1 (1:200 FLEX + Rabbit, CellSignalling, Leiden, Netherlands), Nanog (1:12,800 FLEX + Mouse, CellSignalling, Leiden, Netherlands) and CD44 (1:50 FLEX, CellSignalling, Leiden, Netherlands) was performed with the AutostainerLink 48 (Dako, Hamburg, Germany), incubated for 30 min at room temperature (RT) and incubated another 15 min at RT with the marked polymer EnV FLEX/HRP (Agilent, Hamburg, Germany). The reaction was developed by adding the diaminobenzidine FLEX/DAB + Substrate-Chromogene (Agilent, Hamburg, Germany) and counterstained with haematoxylin (Agilent, Hamburg, Germany) for 3 min at RT. IHC staining with SOX2 (FLEX + Rabbit, Cell Marque, California, USA) was performed with the Dako Omnis (Dako, Hamburg, Germany). Prior to IHC staining with SOX2, the samples were dewaxed with Clearify Clearing Agent for 1 min at 25 °C. Demasking was performed by applying EnV FLEX TRS for 30 min at 97 °C. Then, the antibody for SOX2 was added and incubated for 20 min. For blocking, the samples were incubated with EnV FLEX Peroxidase-Blocking for 3 min. As an enhancer EnV FLEX + Rabbit LINKER was applied. The reaction was developed by adding diaminobenzidine FLEX/DAB + Substrat-Chromogene and then counterstaining with haematoxylin. Between each step, the samples were washed with a buffer solution.

H-score was applied for assessing the extent of immunoreactivity with the following formula:

3 × percentage of strongly staining membrane/cytoplasm/nuclei + 2 × percentage of moderately staining membrane/cytoplasm/nuclei + percentage of weakly staining membrane/cytoplasm/nuclei, giving a range of 0–300 [19]. The H-Score was used by the two examiners in our pathology department. Diverging results were discussed between both examiners.

Calculation of a cutoff-value to define the high or low expression of the markers were performed with a ROC-curve and Youden-Index with the program easyROC version 1.3 [20]. Cutoff-values of the markers were as the following: BMI-1 cutoff at 190; CD44 cutoff at 255; SOX2 cutoff at 30. For calculation of ALDH1 and Nanog lack of staining was considered as a low expression. The clustering heat map was generated via the software Cluster, version 3.0 (Stanford University, Stanford, USA; https://www.encodeproject.org/software/cluster/).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the software Statistica, version 13.1 (StatSoft Europe, Hamburg, Germany) with values statistically significant at p < 0.05. Statistical differences between groups were calculated by the log-rank test and Mann–Whitney-U test. Overall survival (OS), disease-specific-survival (DSS), recurrence-free-survival (RFS) and the local control-rate (LCR) were calculated starting from the date of primary surgery by application of the Kaplan–Meier method. Calculating OS, death for any reason was considered as an event, and patients alive at last follow-up were censored. Regarding DSS, events were defined as death related to the primary tumour alone, and other causes of death were considered as censored. Concerning RFS, local and/or regional recurrences, distant metastasis or death-related to primary diagnosis were considered as events. Whereas, intercurrent-death or death related to secondary primaries, and patients alive without any disease-manifestation accounted for censored observations. In LCR, local recurrences were considered as events. Correlation of expression of CSCs with clinicopathological data was performed by the chi-square test and odds ratio. In the present study three- and 5 year estimates are presented. For multivariate analysis, we used logistic regression to evaluate the effect of clinicopathological variables. To avoid overfitting, we restricted ourselves to fitting clinicopathological variables that had the smallest p values in the single variable analysis or were deemed potentially biologically relevant. The model was fitted using the package glm with the software R (Build 3.2.5 for Windows, The R Project for Statistical Computing, https://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Patients and disease characteristics

Mean age was 64.4 ± 16.9 years, follow-up was 41.8 ± 42.0 months. Different histopathological subtypes were summarized as adenocarcinomas and are depicted in Fig. 1b. 50% (n = 20) were staged a T1-2 tumour, and 52.5% (n = 21) did not exhibit a locoregional metastasis at the time of diagnosis. 52.5% (n = 21) had a G2-graded adenocarcinoma, and in 90% (n = 36) of the patients a R0-resection was reached. Regarding treatment, 50% (n = 20) received the resection of the tumour along with a neck dissection and postoperative radiotherapy. A subset of 15 patients (37.5%) received a resection of the tumour with neck dissection, thereof in 10 patients an indication for postoperative radiotherapy was declined by the tumour board, two patients rejected this adjuvant therapy, and in three the radiotherapy was aborted due to complication issues. Three patients received tumour resection alone, of which in one patient no adjuvant therapy was recommended by the interdisciplinary tumour board, and the other two patients rejected the postoperative radiotherapy, as well as a following salvage surgical treatment. Two patients received a resection of the tumour with postoperative radiotherapy. All data regarding patients and disease characteristics are depicted in Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry

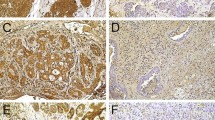

The complete cohort was analysed for high or low expression of the CSC ALDH1, BMI-1, CD44, Nanog, and SOX2. BMI-1 was highly expressed in 52.5% (n = 21) of the cohort, CD44 in 30% (n = 12). In terms of expression of ALDH1, Nanog, and SOX2, most of the cohort showed a low expression. Detailed data are shown in Table 1. Exemplary immunohistochemical staining for low and high expression is depicted in Fig. 2a–e.

Immunohistochemical staining with low and high expression of the cancer stem cell markers ALDH1, BMI-1, CD44, Nanog, and SOX2. (a) Immunostaining with ALDH1: low expression (left; × 10) in a ductal adenocarcinoma, high expression (right; × 10) in an adenoidcystic carcinoma. (b) Immunostaining with BMI-1: low expression (left; × 20) in an adenocarcinoma, high expression (right; × 20) in a salivary duct carcinoma. (c) Immunostaining with CD44: low expression (left; × 40) in a salivary duct carcinoma, high expression (right; × 20) in an adenocarcinoma. (d) Immunostaining with Nanog: low expression (left; × 20) in a mucoepidermoid carcinoma, high expression (right; × 20) in a mucoepidermoid carcinoma. (e) Immunostaining with SOX2: low expression (left; × 20) in a mucoepidermoid carcinoma, high expression (right; × 20) in a polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma

Correlation of patient and disease characteristics with CSC

Concerning an association of CSCs with clinicopathological parameters, a strong correlation of ALDH1 expression and higher histopathological grading (G1 vs. G2-3) was observed (p < 0.001). Expression of CD44 significantly correlated with the localization of the neoplasm (parotid vs. submandibular gland; p = 0.050), a larger tumour size (T1-2 vs. T3-4; p = 0.006), positive N-category (p = 0.023), and advanced UICC stage III-IV (p = 0.002). Regarding a high expression of SOX2, a significant association with a negative perineural invasion was observed (p = 0.020). In terms of BMI-1 and Nanog, no correlation was shown within this cohort (Table 2). To find a correlation upon patient and disease characteristics, a hierarchical clustering heat map was performed (Supplemental Fig. 1). By generating the heat map, two groups were identified: Group 1 contained tumour samples with high expression of BMI-1/CD44, and low expression of ALDH1/Nanog/SOX2, which correlated significantly with a higher grading (G1 vs. G2/3; p = 0.029). Group 2 was characterised by tumour samples exhibiting low expression of BMI-1/CD44 and high expression of ALDH1/Nanog/SOX2 associated with a lower grading (Supplemental Table 1). Results of the corresponding multivariate analysis are displayed in Supplemental Table 2.

Correlation of patient and disease characteristics and CSC with survival rates

Three- and 5 year survival-estimates (OS, DSS, RFS, LCR) were correlated with patient and disease characteristics, as well as expression of CSC (Table 3). Concerning histopathological grading, significant differences in both three- and 5 year survival rates between G1-2 and G3 with regard to OS (5 year-estimates: 87.0 vs. 20.2%; p < 0.001), DSS (5 year-estimates: 100.0 vs. 38.1%; p < 0.001), and RFS (5 year estimates: 83.3 vs. 40.5%; p = 0.043) were seen. Comparison of UICC stages showed a significant difference in RFS between UICC I-II and UICC III-IV (5 year-estimates: 90.0 vs. 61.9%; p = 0.030). Overall, no statistically significant differences were found regarding survival rates of high and low expression of the examined CSCs. Same findings were observed in the results of hierarchical clustering (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

The current study found no significant differences in survival-rates with regard to the investigated CSCs BMI-1, CD44, ALDH-1, Nanog, and SOX2. Concerning a correlation with disease characteristics, an association of high expression of ALDH1 with grading, high expression of CD44 with localization of the neoplasm, T- and N-category, and UICC stage, as well as high expression of SOX2 with perineural invasion was observed. Regarding IHC, the cohort of adenocarcinoma of the major salivary glands showed a predominantly high expression of BMI-1. Significant lower survival-estimates correlated with a high-grade histopathological disease.

Since salivary gland malignoma is a rather rare entity [1], clinicopathological data is scarce. To date, only 9 studies have examined the prognostic value of CSCs in adenocarcinoma of the major and minor salivary glands (Table 4). Our study is the only one so far to evaluate the correlation of the markers ALDH1, BMI-1, CD44, Nanog, and SOX2 with survival-rates and clinicopathological data in adenocarcinoma of the major salivary glands. The limitations lie in the retrospective nature and small evaluated cohort of the study. To apply a sound statistical comparison, higher numbers would be preferable.

The cohort of the present study consists of a comparable sample size when looking at other studies which analysed CSCs in adenocarcinomas of the salivary glands [21, 22]. Concerning the distribution of patients and disease characteristics, the data of our study is in line with the literature, where a large cohort of 4068 patients with malignoma of the salivary glands from the National Cancer Database (NCDB) of the American Cancer Society and Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons was investigated with regard to postoperative radiotherapy on survival-estimates [3].

In terms of ALDH1, an association of low expression with higher histopathological grading was observed. Zhou et al. observed a high ALDH1-expression in stromal cells of their cohort of 216 patients with adenoidcystic carcinoma; however, a significant correlation to survival-estimates was not found [23]. Sun et al. showed a high correlation of high ALDH-1-levels in adenoidcystic carcinoma with higher tumorigenic, invasive, and metastatic properties [24]. Regarding other tumour entities, diverging results in terms of a prognostic parameter were found. For example, in endometroid cancer higher ALDH1-expression correlated with longer overall and disease-free survival [25]; whereas, the study group around Chen et al. reported of a positive correlation of ALDH1 expression with a negative outcome in HNSCC [10].

Regarding BMI-1, our cohort exhibited a high expression in half of the cases, without correlation to neither survival-estimates nor clinicopathological parameters. Yi et al. found a high correlation of metastatic disease with expression of BMI-1 in a cohort of 102 patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma [26]. Whereas Destro Rodrigues et al. did not observe any correlation to survival-estimates or prognostic parameters [27]. Concerning other cancer entities, previously Koren et al. found a low expression of BMI-1 in 96 advanced staged non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in comparison to their control group of healthy individuals. Furthermore, they observed a correlation of high BMI-1 with longer progression-free and overall survival in advanced NSCLC patients [28]. Also, an association with high BMI-1-expression was observed in breast cancer, melanoma, gastric cancer, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma [12, 29]. CD44 showed a low expression in the majority of our carcinoma, mucoepidermoid-carcinoma, and other types of adenocarcinoma as investigated in our cohort [21, 27, 30, 31]. Regarding survival-estimates, we did not observe any correlation with CD44 when tested alone. Concerning an association with clinical parameters, a correlation with the tumour localization, tumour size, nodal status, and prognostic UICC stage was observed. Since CD44 is recognized as a pivotal marker for the cancer stem cells [13], a correlation with malignant clinicopathological characteristics and the worse prognosis seems consistent. The group of Xu et al. observed a strong correlation with a significantly increased overall survival in patients showing high expression of CD44, CD133, and SOX2 combined either all together, or CD44 with one of the other both markers. An association of one of the three markers alone with clinicopathological data was not observed [31]. In contrast, Soave and collaborators tested CD44 combined with CD24 in adenocarcinomas of the salivary glands, and found a strong correlation with tumour size and lymph node metastasis [21]. Wang et al. observed a strong correlation of high CD44-expression with distant metastasis, histologic pattern, perineural-invasion, vascular-invasion, and clinical stage [32]. Regarding HNSCC, diverging results were described. An older study by Mack and Gires specifically investigated the expression pattern of CD44 variants (CD44s and CD44v6) in HNSCC, and found no difference between benign and malignant tissue [33]. Whereas several recent studies observed a high expression of CD44 [34,35,36]. Concerning other tumour entities, the CD44 expression and its prognostic significance are well-studied, e.g. in breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and endometroid cancer [37, 38].

Investigating Nanog, our cohort showed a predominantly low expression with no significant correlation upon survival-rates or clinicopathological parameters. Solely a trend to a positive perineural-invasion was observed. Two other studies showed similar results investigating patients with adenoidcystic or mucoepidermoid-carcinoma [23, 31]. In contrast, Destro Rodrigues and collaborators observed a high expression of Nanog correlated with a perineural-invasion in patients with mucoepidermoid-carcinoma [27]; an association with survival-estimates was not observed. Investigations of other tumour entities showed promising prognostic values of Nanog in endometrioid carcinoma [37], liver cancer, lung cancer, and HNSCC [18].

In our cohort, SOX2 showed a low expression with no correlation to survival-estimates. Regarding clinicopathological parameters, an association with a negative perineural status was observed. Other studies found a high expression of SOX2 together with a correlation with clinical staging. Xu et al. did not observe any correlations when analysing SOX2 alone. However, a high expression of SOX2 in combination with CD44/CD133 showed a significant lower OS [31]. Dai and co-workers found a significant correlation of high SOX2 expression with advanced T-category, distant metastasis, OS, and DFS in patients with adenoidcystic carcinoma [39]. Sedassari et al. found an association with T-category, distant metastasis, grading, recurrence rate, and adverse outcome in their cohort of 30 patients with carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma [40]. In terms of other tumour entities, a prognostic correlation of SOX2 in colon cancer [41], breast cancer [42], and HNSCC [3] is well-documented.

The expression of stem cell markers such as ALDH1, BMI-1, CD44, Nanog, and SOX2 is well-investigated for other tumour entities, and has shown promising results as prognostic parameters with potential as a target for cancer treatment [43, 44]. Malignoma of the salivary glands is rare per se, with rather worse prognosis [1]. Retrospective analyses in literature have found clinical staging as a main prognostic factor [4, 21, 45]. Clinical prospective studies do not exist due to the low incidence of the disease. Regarding clinicopathological studies, 9 studies investigated a correlation of certain CSCs with survival-rates and clinical stages to date (Table 4). Unfortunately, the heterogeneity of cohorts, applied methods, and investigated CSCs differ significantly, therefore, a sound conclusion of those diverging results seems impossible. Regarding the results of our study and the literature, the CSCs ALDH1, BMI-1, CD44, Nanog, and SOX2 seem not to serve as reliable prognostic parameters in adenocarcinomas of the salivary glands.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study found no significant correlation of the investigated CSCs ALDH1, BMI-1, CD44, Nanog, and SOX2 with survival-estimates in adenocarcinoma of the major salivary glands. However, observed were a high ALDH1-expression associated with higher grading, a high CD44-expression with localization of the neoplasm, advanced pT- and pN-category, and UICC-stage, as well as a high SOX2-expression with negative perineural invasion.

Recapitulating the results of our study in conjunction with the literature, the CSCs ALDH1, BMI-1, CD44, Nanog, and SOX2 do not seem to serve as reliable novel prognostic parameters in the treatment of adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands.

Data availability

Original data are available on demand.

Code availability

Statistical analysis was performed with the software Statistica, version 13.1 (StatSoft Europe, Hamburg, Germany). The respective codes are available on demand.

References

Barnes L, Eveson J, Reichart P, Sidransky D (2005) Tumours of the salivary glands. In: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. IARC Press, Lyon, France,

Leivo I (2006) Insights into a complex group of neoplastic disease: advances in histopathologic classification and molecular pathology of salivary gland cancer. Acta Oncol 45(6):662–668

Safdieh J, Givi B, Osborn V, Lederman A, Schwartz D, Schreiber D (2017) Impact of adjuvant radiotherapy for malignantsalivary gland tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 157(6):988–994

Guzzo M, Locati L, Prott F, Gatta G, McGurk M (2010) Major and minor salivary gland tumors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 74(2):134–148

Lagha A, Chraiet N, Ayadi M, Krimi S, Allani B, Rifi H, Raies H, Mezlini A (2012) Systemic therapy in the management of metastatic or advanced salivary gland cancers. Head Neck Oncol 4(1):19

Reya T, Morrison S, Clarke M, Weissman I (2001) Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 414(6859):105–111

Nguyen L, Vanner R, Dirks P, Eaves C (2012) Cancer stem cells: an evolving concept. Nat Rev Cancer 12(2):133–143

Prince M, Sivanandan R, Kaczorowski A, al. e, (2007) Identification of a subpopulation of cells with cancer stem cell properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America 104(3):973–978

Douville J, Beaulieu R, Balicki D (2009) ALDH1 as a functional marker of cancer stem and progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev 18(1):17–25. https://doi.org/10.1089/scd.2008.0055

Chen Y, Chen Y, Hsu H, Tseng L, Huang P, Lu K, Chen D, Tai L, Yung M, Chang S, Ku H, Chiou S, Lo W (2009) Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a putative marker for cancer stem cells in head and neck squamous cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 385(3):307–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.048

Park I, Qian D, Kiel M, Becker M, Pihalja M, Weissman I, Morrison S, Clarke M (2003) Bmi-1 is required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 423(6937):302–305. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01587

Paranjape A, Balaji S, Mandal T, Krushik E, Nagaraj P, Mukherjee G, Rangarajan A (2014) Bmi1 regulates self-renewal and epithelial to mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells through Nanog. BMC Cancer 14:785. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-785

Toole B (2009) Hyaluronan-CD44 interactions in cancer: paradoxes and possibilities. Clin Cancer Res 15(24):7462–7468

Joshua B, Kaplan M, Doweck I, Pai R, Weissman I, Prince M, Ailles L (2012) Frequency of cells expressing CD44, a head and neck cancer stem cell marker: correlation with tumor aggressiveness. Head Neck 34(1):42–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.21699

Mitsui K, Tokuzawa Y, Itoh H, Segawa K, Murakami M, Takahashi K, Maruyama M, Maeda M, Yamanaka S (2003) The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell 113(5):631–642

Chiou S, Yu C, Huang C, Lin S, Liu C, Tsai T, Chou S, Chien C, Ku H, Lo J (2008) Positive correlations of Oct-4 and Nanog in oral cancer stem-like cells and high-grade oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 14(13):4085–4095. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4404

Boumahdi S, Driessens G, Lapouge G, Rorive S, Nassar D, Le Mercier M, Delatte B, Caauwe A, Lenglez S, Nkusi E, Brohée S, Salmon I, Dubois C, del Marmol V, Fuks F, Beck B, Blanpain C (2014) SOX2 controls tumour initiation and cancer stem-cell functions in squamous-cell carcinoma. Nature 511(7508):246–250. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13305

Baillie R, Tan S, Itinteang T (2017) Cancer stem cells in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: a review. Front Oncol 7:112. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2017.00112.eCollection2017

Ishibashi H, Suzuki T, Suzuki S, Moriya T, Kaneko C, Takizawa T, Sunamori M, Handa M, Kondo T, Sasano H (2003) Sex steroid hormone receptors in human thymoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88(5):2309–2317

Goksuluk D, Korkmaz S, Zararsiz G, Karaağaoğlu A (2016) easyROC: an interactive web-tool for ROC curve analysis using R language environment. The R Journal 8(2):213–230

Soave D, Oliveira da Costa J, da Silveira G, Ianez R, de Oliveira L, Lourenço S, Ribeiro-Silva A (2013) CD44/CD24 immunophenotypes on clinicopathologic features of salivary glands malignant neoplasms. Diagn Pathol 8:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-8-29

Destro Rodrigues M, Sedassari B, Esteves C, de Andrade N, Altemani A, de Sousa S, Nunes F (2017) Embryonic stem cells markers Oct4 and Nanog correlate with perineural invasion in human salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med 46(2):112–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.12449

Zhou J, Hanna E, Roberts D, Weber R, Bell D (2013) ALDH1 immunohistochemical expression and its significance in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Head Neck 35(4):575–578. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.23003

Sun S, Wang Z (2010) ALDH high adenoid cystic carcinoma cells display cancer stem cell properties and are responsible for mediating metastasis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 369(4):843–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.170

Chang B, Liu G, Xue F, Rosen D, Xiao L, Wang X, Liu J (2009) ALDH1 expression correlates with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancers. Mod Pathol 22(6):817–823. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.35

Yi C, Li B, Zhou C (2016) Bmi-1 expression predicts prognosis in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma and correlates with epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related factors. Ann Diagn Pathol 22:38–44

Rodrigues M, Xavier F, Andrade N, Lopes C, Miguita Luiz L, Sedassari B, Ibarra A, López R, Kliemann-Schmerling C, Moyses R, Tajara da Silva E, Nunes F (2018) Prognostic implications of CD44, NANOG, OCT4, and BMI1 expression in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck 40(8):1759–1773. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25158

Koren A, Rijavec M, Sodja E, Kern I, Sadikov A, Kovac V, Korosec P, Cufer T (2017) High BMI1 mRNA expression in peripheral whole blood is associated with favorable prognosis in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Oncotarget 8(15):25384–25394. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15914

Xu X, Liu Y, Su J, Li D, Hu J, Huang Q, Lu M, Liu X, Ren J, Chen W, Sun L (2016) Downregulation of Bmi-1 is associated with suppressed tumorigenesis and induced apoptosis in CD44(+) nasopharyngeal carcinoma cancer stem-like cells. Oncol Rep 35(2):923–931. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2015.4414

Binmadi N, Elsissi A, Elsissi N (2016) Expression of cell adhesion molecule CD44 in mucoepidermoid carcinoma and its association with the tumor behavior. Head Face Med 29(12):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13005-016-0102-4

Xu W, Wang Y, Qi X, Xie J, Wei Z, Yin X, Wang Z, Meng J, Han W (2017) Prognostic factors of palatal mucoepidermoid carcinoma: a retrospective analysis based on a double-center study. Sci Rep 7:43907. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43907

Wang Y, Chen W, Huang Z, Yang Z, Zhang B, Wang J, Li H, Li J (2011) Expression of the membrane-cytoskeletal linker Ezrin in salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 112(1):96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.02.018

Mack B, Gires O (2008) CD44s and CD44v6 expression in head and neck epithelia. PLoS ONE 3(10):e3360. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003360

Ludwig N, Szczepanski M, Gluszko A, Szafarowski T, Azambuja J, Dolg L, Gellrich N, Kampmann A, Whiteside T, Zimmerer R (2019) CD44(+) tumor cells promote early angiogenesis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett 467:85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2019.10.010

Chai L, Liu H, Zhang Z, Wang F, Wang Q, Zhou S, Wang S (2014) CD44 expression is predictive of poor prognosis in pharyngolaryngeal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Tohoku J Exp Med 232(1):9–19

Rajarajan A, Stokes A, Bloor B, Ceder R, Desai H, Grafström R, Odell E (2012) CD44 expression in oro-pharyngeal carcinoma tissues and cell lines. PLoS ONE 7(1):e28776. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028776

Park J, Hong D, Park J (2019) Association between morphological patterns of myometrial invasion and cancer stem cell markers in endometrial endometrioid carcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res 25(1):123–130

Wang Z, Tang Y, Xie L, Huang A, Xue C, Gu Z, Wang K, Zong S (2019) The prognostic and clinical value of CD44 in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Front Oncol 9:309. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00309

Dai W, Tan X, Sun C, Zhou Q (2014) High expression of SOX2 is associated with poor prognosis in patients with salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 15(5):8393–8406. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms15058393

Sedassari B, Rodrigues M, Conceição T, Mariano F, Alves V, Nunes F, Altemani A, de Sousa S (2017) Increased SOX2 expression in salivary gland carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma progression: an association with adverse outcome. Virchows Arch 471(6):775–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-017-2220-1

Neumann J, Bahr F, Horst D, Kriegl L, Engel J, Luque R, Gerhard M, Kirchner T, Jung A (2011) SOX2 expression correlates with lymph-node metastases and distant spread in right-sided colon cancer. BMC Cancer 11:518

Lengerke C, Fehm T, Kurth R, Neubauer H, Scheble V, Müller F, Schneider F, Petersen K, Wallwiener D, Kanz L, Fend F, Perner S, Bareiss P, Staebler A (2011) Expression of the embryonic stem cell marker SOX2 in early-stage breast carcinoma. BMC Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-11-42

Medema J (2013) Cancer stem cells: the challenges ahead. Nat Cell Biol 15(4):338–344. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2717

Wang T, Shigdar S, Gantier M, Hou Y, Wang L, Li Y, Shamaileh H, Yin W, Zhou S, Zhao X, Duan W (2015) Cancer stem cell targeted therapy: progress amid controversies. Oncotarget 6(42):44191–44206

Hocwald E, Korkmaz H, Yoo G, Adsay V, Shibuya T, Abrams J, Jacobs J (2001) Prognostic factors in major salivary gland cancer. Laryngoscope 111(8):1434–1439

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the support and work of Stefan Küffer, PhD (Department of Pathology, Georg-August-University of Goettingen, Goettingen, Germany) for performing and analysing the histological sections. We are grateful to all patients and clinical colleagues who donated or collected clinical samples.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jennifer L. Spiegel analysed and interpreted data, and wrote the paper. Mark Jakob conceptualized the study, designed the experiments and provided critical revision. Marie Kruizenga performed experiments, collected and analysed data, and provided critical revision. Saskia Freytag performed additional statistical analyses. Mattis Bertlich, Martin Canis, Friedrich Ihler, and Frank Haubner interpreted data and provided critical revision. Julia Kitz performed experiments, interpreted data, and provided critical revision. Bernhard G. Weiss conceptualized the study, designed the experiments, collected, analysed and interpreted data, and provided critical revision. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Study protocol was performed according to ethical guidelines of the 2002 Declaration of Helsinki and carried out after approval by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the University Medical Centre Göttingen (reference number 2/1/17). All patients gave written consent to the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Spiegel, J.L., Jakob, M., Kruizenga, M. et al. Cancer stem cell markers in adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands - reliable prognostic markers?. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 278, 2517–2528 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06389-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06389-7