Abstract

Purpose

We present our case series of four adult patients with Pott’s puffy tumour (PPT), successfully treated with Draf III over a mean period of 11 months. A critical review of the literature is also provided.

Methods

A retrospective review of patients undergoing Draf III for PPT from January 2018 to January 2019 was performed.

Results

Four consecutive male patients ranging from 26 to 62 years, with a mean age of 49.5 ± 16.3 years, undergoing Draf III for Pott’s puffy tumour were included. Two patients had a Kuhn type IV frontal cell narrowing the frontonasal pathway and presented without previous sinus surgery, whereas the other two had previous sinus surgery. The success rate of the operation was 100% with an average length of follow-up of 11 months (range 5–18).

Conclusion

In our experience, the Draf III procedure is a highly effective treatment of PPT. In particular, we have demonstrated it to be very effective in accessing highly positioned Kuhn type IV cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pott’s puffy tumour (PPT) is a subperiosteal abscess of the anterior frontal plate associated with osteomyelitis. It was first described by Sir Percivall Pott in 1775 as a complication of a frontal sinusitis [1]. It is a relatively rare but serious condition usually presenting as a localized swelling of the forehead, and can be associated with periorbital oedema, purulent nasal discharge, fever, headache and vomiting. Occasionally, it may cause severe intracranial complications like meningitis, epidural abscess, subdural empyema, intracerebral abscess, and dural sinus thrombophlebitis as a result of the spreading of the infection through bony erosions or septic thrombosis [2]. The most frequently affected age group is adolescents, while its occurrence in the adults is considered rare [3,4,5].

Treatment of PPT and prevention of its complications involves a combination of intravenous antibiotics and surgical drainage. Empiric antibiotic therapy consists of broad-spectrum antibiotics with good penetration to central nervous system, commonly clindamycin, ceftriaxone, metronidazole and vancomycin, and it must be started as soon as possible. Then, the antibiotic can be changed accordingly to the results of culture and microbial susceptibility testing, and should be prolonged for at least 6–8 weeks postoperatively [6,7,8].

However, surgical treatment remains the keystone in the management of these patients and may vary from external surgical approach alone, endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) either alone or in combination with external drainage. External approach to the frontal sinus is easy and rapid, and it allows a direct visualization of the sinus. Nonetheless, this approach is associated with facial scars and does not address the frontal sinus blockage causation which theoretically may lead to a relapse of the abscess. ESS approach as well as addressing the site of frontal sinus blockage also prevents the need for an external facial scar [4]. The extend of ESS may vary from a simple (Draf I) to an extended drainage of the frontal sinus (Draf II), with the latter achieved by resecting the floor of the frontal sinus between the lamina papyracea and the middle turbinate (Draf IIa) or between the lamina papyracea and nasal septum (Draf IIb). In some cases, an endonasal median drainage (Draf III or endoscopic modified Lothrop procedure) is required to achieve the maximum possible opening [9]. The challenge whilst addressing the frontal sinus blockage caused by a Kuhn type IV cell [10] is whether endoscopically it can be reached and cleared properly. Evidence in the literature demonstrating the long-term outcomes of Draf III for the surgical treatment of PPT is poor and whether Draf III can be used in all cases, especially in those with frontal sinus obstructing cells, has not been reported [11]. We present our case series of four adult patients with PPT successfully treated with Draf III over a mean period of 11 months, including two with highly placed obstructing Kuhn type IV cells.

Materials and methods

A retrospective review of patients undergoing Draf III for PPT from January 2018 to January 2019 at the Royal National Throat Nose and Ear Hospital, London, United Kingdom was performed. The diagnosis was confirmed by clinical examination and imaging (CT and MRI scan). Population data including clinical presentation, imaging, surgical operative reports final outcomes, interval between diagnosis and treatment, pre- and post-operative medical treatment, length of follow-up were recorded and analysed. Formal ethical approval was not required because all the data were processed through local hospital trust audit policy. All investigations and treatments were carried out in line with accepted clinical practice.

Surgical technique

Draf III, also called endonasal median drainage or modified endoscopic Lothrop procedure, was performed under general anaesthesia and with image guidance assistance. In this procedure, a wide opening between the two frontal sinuses and the nasal cavity is achieved. Once an opening of frontal sinus between lamina papyracea and nasal septum (Draf IIb) has been performed bilaterally, the frontal sinus floor in front of the olfactory cleft and the intersinus septum is removed. The middle turbinate is resected very gently from an anterior to posterior direction, along its origin at the skull base. A diamond burr drill is used to reduce the frontal beak and the frontal intersinus septum or septa, if more than one is present [9]. Finally, the nose is packed with varnished whitehead ribbon gauze or absorbable packs soaked in betamethasone 0.1% drops to reduce scarring and post-operative oedema.

Results

Population

Four consecutive male patients ranging from 26 to 62 years, with a mean age of 49.5 ± 16.3 years, undergoing Draf III for PPT were included. Clinical and demographic data are summarized in Table 1.

Clinical presentation and history

All patients presented to the Emergency Department with a forehead swelling and headache overlying the frontal sinuses. All but one had a history of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) without nasal polyps with only one patient having nasal polyps under medical treatment. Two patients had a history of previous sinonasal surgery for their CRS. None of them had intracranial complications at presentation. All patients received broad spectrum intravenous antibiotic with good penetration to the central nervous system before undergoing Draf III. Two patients had already had ESS with simple frontal sinus drainage (Draf I) with or without external drainage. Unfortunately, PTT recurred in all of them and they underwent Draf III under our care. In another patient, Draf III was chosen as the first approach from the beginning based on the presence of an unfavourable frontal sinus anatomy at the CT scan.

Imaging

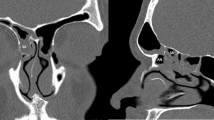

PTT was diagnosed preoperatively by means of CT and MRI scans. In one patient, the CT scan showed an asymptomatic meningeal enhancement. Two patients had a Kuhn type IV cell obstructing the frontal recess (Fig. 1). CT scan was performed post-operatively in all the patients to rule out any intracranial complication, stenosis or recurrence (Table 1, Figs. 2, 3). Patients two and four were lost earlier at follow-up, while the other two patients had a longer follow-up and received a second post-operative CT scan to evaluate long-term results (Table 1).

Post-operative CT scan of the 59-year-old male, 9 months after Draf III. Kuhn type IV cell has been opened and is not visible at the CT scan. There is residual inflammation in the frontal sinus which is compatible with the underlying chronic rhinosinusitis. A wider sinonasal frontal cavity has been obtained. a Axial, b coronal and c sagittal view. d 3D reconstruction

a–c Sequential slices in coronal view of the pre-operative CT scan of the 26-year-old male presenting with pott’s puffy tumour. Please note the osteitis of the frontal bone blocking the frontonasal pathway as a result of the previous endoscopic sinus surgeries and the ongoing inflammation. d–f Sequential slices in coronal view of the post-operative CT scan 13 months after Draf III

Outcomes

Draf III was successful in all cases. There were no acute complications. Histology of the specimens showed inflammatory mucosa in all cases. Microbiology culture was positive for Streptococcus milleri in one case while showed normal flora in the rests. All patients received broad-spectrum antibiotics with good central nervous system penetration postoperatively for at least 2 weeks and adjusted according to microbiology findings. In our experience, following Draf III surgery, patients benefit from a long-term course of macrolide treatment for at least a further 8 weeks (clarithromycin 500 mg daily for 8 weeks). Patients are started on a short course of oral steroid (prednisolone 40 mg daily for 5 days), if not contraindicated. Nasal douches with normal saline are highly recommended at least twice a day followed by intranasal steroid drops (bethamethasone sodium phosphate 0.1%, 2 drops each nostril twice a day) in the “Kaiteki” position were also suggested for 4 weeks. At 4 weeks, patients are debrided in out-patients under local anaesthetic whereby crusts and debris are removed. Out of the four patients, only one required endoscopic nasal de-crusting under general anaesthesia 2 weeks after the operation. One patient developed sinusitis within the first month postoperatively, which eventually resolved with oral antibiotics. Once the cavity starts stabilising at 4 weeks, patients continue with douching and commence Fluticasone propionate 400 μg nasal drops (400 μg divided between the nostrils) twice a day.

Follow-up

The success rate of the operation was 100% with an average length of follow-up of 11 months (range 5–18). All patients were followed up with nasendoscopy in an outpatient setting and none of them required revision surgery for recurrence.

Discussion

PPT most frequently occurs in paediatric and adolescent populations while it is considered rare in adults [12]. In young people, PPT is considered more prevalent as a result from either an anatomically undeveloped frontal sinus or an increased blood flow within the diploic veins found in adolescence [13, 14]. In the adults, the main cause of PPT is stenosis of the frontoethmoidal duct, as a result of recurrent sinusitis or head surgery/trauma [14, 15]. CRS is considered as a risk factor for PPT development [16, 17], and all of our patients had a history of CRS with or without nasal polyps. It has also been speculated that the status of the host and his past history are important factors in adult cases. Underlying diseases such as diabetes, chronic renal failure, and aplastic anaemia have been reported to be developing risk factors but not clear exacerbating factors of PPT. Intranasal cocaine use has also been described as a predisposing factor related to its ability to compromise bones and generate intranasal inflammation [14]. A male to female preponderance has also been reported [3, 18] and our study strongly confirms this with all four cases being male.

In our cohort of four patients, we identified two main causes for PPT. The first cause appears to be frontal sinus ostium stenosis following previous sinus surgery which has been already described in the literature as a risk factor for PPT development. Repeated frontal sinus surgery, in fact, can cause a bony remodelling with a potential narrowing of the frontonasal duct (Fig. 3). The second cause was the presence of a highly placed Kuhn type IV cell resulting in frontal sinus obstruction which we found in two of our cases (Fig. 1). Kuhn type IV cells are single, but isolated cells found within the frontal sinus [10, 19], which can be found with a frequency ranging from 1.3% to 8.5% [10, 20]. The origin of the isolated frontal cell (Kuhn type IV cell) remains unclear and updated frontal sinus classification systems postulate it to be related to the midline intersinus septum [21]. The presence of frontal cells, especially of a Kuhn type III or IV cell, has been reported to correlate with a significantly higher incidence of frontal sinus disease [22] as well as frontal sinus revision surgery [23]. However, to our knowledge, a Kuhn type IV cell has never been described as a risk factor for PPT development. In our opinion, this type of cell, even if rarely found, can create a higher and distal block of the sinonasal pathway with an increased risk of frontal sinusitis and consequent potential complications. This risk becomes even higher if one or more additional risk factors of the above-mentioned are present.

Until recently, the surgical treatment of PPT involved many techniques and predominantly an external approach. In a recent review of the literature which included 83 paediatric and adolescent patients surgically treated for PPT, Koltsidopoulos et al., reported that an external approach was used in most of the cases (46.5%), while an endoscopic treatment was used alone in 20% of cases and in combination with an external drainage in 27% of cases. In the remaining cases (3.5%), no surgical treatment was adopted [24]. In another review of the literature published in 2012 including 32 adult patients with PPT after 1990, Akiyama and colleagues reported that external surgical procedure was chosen in 58.1% of the cases, but ESS in combination with an external subperiosteal abscess drainage was adopted in 32.9% of the rest. Only forehead drainage treatment without radical drainage surgery for frontal sinuses was performed in three cases (9.7%). Recurrence was observed in two of the patients undergoing sinus surgery [14]. In 2017, Şimşek reported one case of PPT treated by means of an external approach to drain the abscess and remove the osteomyelitic bone combined with an endoscopic enlargement of the frontonasal duct [25]. Similarly Geyton and colleague performed ESS with external drainage of frontal sinus abscess in a 45-year-old man presented with PPT [26], while Tatsumi et al., performed successfully ESS alone, even if they did not report the extent of the sinus surgery [27]. More recently, another two cases have been reported by two different authors. However, both combined endoscopic and external surgical approach with drainage of the abscess and debridement of necrotic material [5, 28].

Evidence is not available to determine the extent of endoscopic sinus surgery required to prevent recurrence of PPT. Van der Poel et al., in their case series of six paediatric patients successfully used Draf IIa in five cases even if they reported a high rate of re-stenosis with two patients undergoing a Draf IIa revision and another one requiring a Draf III to treat a mucocele [4].

Current indications for a Draf III procedure include; persistent chronic frontal sinusitis with failure of endoscopic frontal surgery, frontal sinus mucoceles, inverted papilloma, osteoma and trauma [29]. In our experience, Draf III should be also considered the procedure of choice in patients with PPT including those with an isolated frontal sinus obstructing cell (i.e., Kuhn type IV cell).

The issue over post-operative care following Draf III is crucial with the need to treat post-operative crusting. Patients will require endoscopic debridement under local anaesthesia at week 3 and potentially week 6. We recommend frequent nasal douches as well as intranasal steroid drops in the “Kaiteki” position to allow for delivery of the drug to the frontal sinuses [30]. We also suggest long-term macrolide antibiotics for 8 weeks in view of their anti-inflammatory and immune-mediating properties [31], compatible with the antibiogram of the microbiology sent out during the procedure. However, there are cases where this fails according to the literature. Sekine et al., described an immunocompromised case of recurrent PPT after a combination of incisional drainage (× 2) and a Draf III who was eventually treated with a combination of repeat ESS, craniotomy, and frontal sinus reconstruction using an anterolateral thigh flap [32]. Similarly, Leong reported a recurrence in one of his two patients undergoing Draf III for PTT [33]. In those recurrent cases, craniotomy and total removal of the affected tissue should be considered.

The optimum timing for PPT surgery, either external or endoscopic frontal sinus surgery, has not been determined. Akiyama et al., reported no correlation between the time from onset to surgery and the incidence of intracranial complications [14]. In the planning of a Draf III procedure for PPT, we advise early administration of intravenous antibiotic and corticosteroids which may help reducing the inflammatory state and thus diminishing the intraoperative bleeding and the risk of surgical complication.

Conclusions

In our experience, the Draf III procedure is a highly effective treatment of PPT. In particular, we have demonstrated it to be very effective in accessing highly positioned Kuhn type IV cells. This particular frontal sinus anatomical variant is rare but appeared to be a risk factor in our cohort.

References

Flamm ES (1992) Percivall Pott: an 18th century neurosurgeon. J Neurosurg 76:319–326

Bambakidis NC, Cohen AR (2001) Intracranial complications of frontal sinusitis in children: Pott’s puffy tumor revisited. Pediatr Neurosurg 35:82–89

Ketenci I, Ünlü Y, Tucer B, Vural A (2011) The Pott’s puffy tumor: a dangerous sign for intracranial complications. Eur Arch Oto Rhino Laryngol 268:1755–1763

van der Poel NA, Hansen FS, Georgalas C, Fokkens WJ (2016) Minimally invasive treatment of patients with Pott’s puffy tumour with or without endocranial extension: a case series of six patients: our experience. Clin Otolaryngol 41:596–601

Koltsidopoulos P, Papageorgiou E, Skoulakis C (2019) Acute sinusitis complicated with Pott puffy tumour. CMAJ 191:E165

Liu A, Powers AK, Whigham AS et al (2015) A child with fever and swelling of the forehead. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 54:803–805

Arora HS, Abdel-Haq N (2014) A 14-year-old male with swelling of the forehead. Pediatr Ann 43:479–481

Stark P, Ghumman R, Thomas A, Sawyer SM (2015) Forehead swelling in a teenage boy. J Paediatr Child Health 51:731–733

Draf W (2005) Endonasal frontal sinus drainage type I-III according to draf. The frontal sinus. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 219–232

Lee WT, Kuhn FA, Citardi MJ (2004) 3D computed tomographic analysis of frontal recess anatomy in patients without frontal sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 131:164–173

Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C et al (2020) European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2020. Rhinology 58:1–464

Keehn B, Jorgensen S, Towbin A, Towbin R (2018) Article Pott’s puffy tumor. In: Appl Radiol. https://appliedradiology.com/articles/pott-s-puffy-tumor. Accessed 26 Mar 2020.

Weinberg B, Gupta S, Thomas MJ, Stern H (2005) Pott’s puffy tumor: sonographic diagnosis. J Clin Ultrasound 33:305–307

Akiyama K, Karaki M, Mori N (2012) Evaluation of adult Pott’s puffy tumor: our five cases and 27 literature cases. Laryngoscope 122:2382–2388

Collet S, Grulois V, Eloy P et al (2009) A Pott’s puffy tumour as a late complication of a frontal sinus reconstruction: case report and literature review. Rhinology 47:470–475

Moser R, Schweintzger G, Uggowitzer M et al (2009) Recurrent Pott’s puffy tumor: atypical presentation of a rare disorder. Wien Klin Wochenschr 121:719–722

Nouraei SAR, Elisay AR, Dimarco A et al (2009) Variations in paranasal sinus anatomy: implications for the pathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis and safety of endoscopic sinus surgery. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 38:32–37

Forgie SE, Marrie TJ (2008) Pott’s puffy tumor. Am J Med 121:1041–1042

Kuhn F (2001) Surgery of the frontal sinus. In: Kennedy D, Bolger W, Zinreich S (eds) Diseases of the sinuses: diagnosis and management. London BC, Decker, pp 281–301

Eweiss AZ, Khalil HS (2013) The prevalence of frontal cells and their relation to frontal sinusitis: a radiological study of the frontal recess area. ISRN Otolaryngol 2013:687582

Wormald PJ, Hoseman W, Callejas C et al (2016) The international frontal sinus anatomy classification (IFAC) and classification of the extent of endoscopic frontal sinus surgery (EFSS). Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 6:677–696

Meyer TK, Kocak M, Smith MM, Smith TL (2003) Coronal computed tomography analysis of frontal cells. Am J Rhinol 17:163–168

DelGaudio JM, Hudgins PA, Venkatraman G, Beningfield A (2005) Multiplanar computed tomographic analysis of frontal recess cells: effect on frontal isthmus size and frontal sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 131:230–235

Koltsidopoulos P, Papageorgiou E, Skoulakis C (2020) Pott’s puffy tumor in children: a review of the literature. Laryngoscope 130:225–231

Şimşek H (2019) Patient presenting with frontal subperiosteal abscess and headache: a case of Pott’s puffy tumour. Br J Neurosurg 33:275–277

Geyton T, Henderson A, Morris J, McDonald S (2017) A case of Pott’s puffy tumour from primary dental infection. BMJ Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2017-222294

Tatsumi S, Ri M, Higashi N et al (2016) Pott’s puffy tumor in an adult: a case report and review of literature. J Nippon Med Sch 83:211–214

Dusu K, Chandrasekharan D, Al Yaghchi C, Quiney R (2019) A huge Pott’s puffy tumour secondary to pansinusitis. BMJ Case Rep 12(4):e229755. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2019-229755

Kountakis SE (2005) Endoscopic modified lothrop procedure. The frontal sinus. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 233–241

Eloy P, Andrews P, Poirrier AL (2017) Postoperative care in endoscopic sinus surgery: a critical review. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 25:35–42

Shen S, Lou H, Wang C, Zhang L (2018) Macrolide antibiotics in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis: evidence from a meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis 10:5913–5923

Sekine R, Omura K, Ishida K, Tanaka Y (2019) Recurrent Pott’s puffy tumor treated with anterior skull base resection with reconstruction of the anterolateral thigh flap. J Craniofac Surg 30:E94–E96

Leong SC (2017) Minimally invasive surgery for Pott’s puffy tumor: is it time for a paradigm shift in managing a 250-year-old problem? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 126:433–437

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pendolino, A.L., Koumpa, F.S., Zhang, H. et al. Draf III frontal sinus surgery for the treatment of Pott’s puffy tumour in adults: our case series and a review of frontal sinus anatomy risk factors. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 277, 2271–2278 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-05980-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-05980-2