Abstract

Purpose

To compare perinatal outcomes between active and routine management in true knot of the umbilical cord (TKUC).

Methods

A retrospective study of singletons born beyond 22 6/7 weeks with TKUC. Active management included weekly fetal heart rate monitoring(FHRM) ≥ 30 weeks and labor induction at 36–37 weeks. Outcomes in active and routine management were compared, including composite asphyxia-related adverse outcome, fetal death, labor induction, Cesarean section (CS) or Instrumental delivery due to non-reassuring fetal heart rate (NRFHR), Apgar5 score < 7, cord Ph < 7, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission and more.

Results

The Active (n = 59) and Routine (n = 1091) Management groups demonstrated similar rates of composite asphyxia-related adverse outcome (16.9% vs 16.8%, p = 0.97). Active Management resulted in higher rates of labor induction < 37 weeks (22% vs 1.7%, p < 0.001), CS (37.3% vs 19.2%, p = 0.003) and NICU admissions (13.6% vs 3%, p < 0.001). Fetal death occurred exclusively in the Routine Management group (1.8% vs 0%, p = 0.6).

Conclusion

Compared with routine management, weekly FHRM and labor induction between 36 and 37 weeks in TKUC do not appear to reduce neonatal asphyxia. In its current form, active management is associated with higher rates of CS, induced prematurity and NICU admissions. Labor induction before 37 weeks should be avoided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This is the first comparative study to evaluate the benefit of weekly fetal monitoring and early labor induction as an active management strategy in umbilical-cord knot. | |

Although there is some indication that active management may decrease fetal death, it does not appear to reduce neonatal asphyxia and is associated with more caesarean sections and induced prematurity. |

Introduction

True knot of the umbilical cord (TKUC) is estimated to occur in 1–1.25% of singleton pregnancies [1,2,3,4]. Prenatal detection of TKUC was first described in 1991 by Collins et al. [5]. Although TKUC does not appear to impact long-term neurological outcome in exposed offspring [6], it has been associated with multiple adverse perinatal outcome including fetal death [1,2,3, 7, 8], non-reassuring fetal heart rate (NRFHR) [3, 7, 9], NRFHR-indicated Cesarean section (CS) [1, 7, 9, 10], meconium-stained amniotic fluid [3, 10], lower Apgar scores [2, 9, 10] and more [1,2,3, 7,8,9,10]. Beyond 37 weeks of gestation, the risk of fetal death is tenfold greater than that of singleton pregnancies without a TKUC [1]. Despite the higher rate of multiple adverse perinatal outcomes associated with TKUC, effective prenatal management strategies have not yet been investigated. This is probably because until recently, prenatal detection of TKUC was rare and inaccurate [7, 9, 11,12,13,14]. With advancements in ultrasound technology, it has recently been shown that TKUC can be accurately diagnosed prenatally, reaching a 96.4% detection rate when the umbilical cord is actively scanned [15]. Thus, the opportunity to assess management strategies has become available. The aim of this study was to compare perinatal outcomes between TKUC patients receiving active management, consisting of weekly fetal heart rate monitoring (FHRM) and labor induction between 36–37 weeks, and those receiving routine management.

Materials and methods

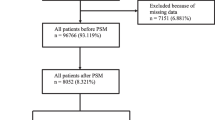

This was a retrospective study of all singletons born at a single tertiary center and diagnosed postnatally with TKUC between 2011 and 2022. Some of the patients in the current study have been reported on in 2 previous studies addressing different aspects of TKUC which were conducted at the same center [1, 15]. Singleton pregnancies that delivered livebirths and stillbirths beyond 22 6/7 weeks of gestation, which were diagnosed postnatally with a TKUC, were included. High-order pregnancies and pregnancies terminated were excluded. The cohort was divided into 2 groups: (1) prenatally detected TKUC patients (Fig. 1) receiving active management (Active Management group) and (2) prenatally undetected TKUC patients receiving routine management (Routine Management group). The local departmental active management protocol included the following: 1. weekly FHRM from 30 weeks of gestation, 2. a growth scan at approximately 32 weeks of gestation and 3. labor induction between 36–37 weeks of gestation, or before, when fetal distress was suspected. Cases that were diagnosed at term were induced upon detection. Routine management included 1. a growth scan at approximately 32 weeks of gestation and 2. fetal well-being assessments beginning at 40 weeks of gestation, including growth assessment, FHRM and biophysical scans, which were conducted at the hospital every 2–3 days until delivery. Labor induction was recommended at 41.6 weeks or earlier in patients who presented other maternal/fetal indications.

The background maternal characteristics, including maternal age, parity, body mass index (BMI), previous cesarean deliveries and trial of labor after cesarean section (TOLAC), were compared between the groups. The perinatal outcomes compared included gestational age at delivery, birthweight, mode of delivery, rates of preterm birth (< 37 weeks), fetal death, labor induction, NRFHR [16], operative vaginal/CS delivery due to NRFHR, meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF), 5-min Apgar (Apgar5) score < 7, umbilical cord pH < 7 (preferably arterial, venous in the absence of arterial), neonatal asphyxia, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), mechanical ventilation, NICU admission and neonatal death before discharge.

A composite asphyxia-related outcome, including fetal death, operative vaginal/CS delivery due to NRFHR, Apgar5 score < 7, umbilical cord pH < 7, neonatal asphyxia, HIE, mechanical ventilation, NICU admission and neonatal death before discharge, was compared between the groups.

Definitions [17]

Neonatal asphyxia was defined as organ impairment presenting immediately after birth caused by compromised tissue oxygenation resulting from a suspected prenatal hypoxic event, characterized by NRFHR, a low APGAR score or a low cord Ph.

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy was defined as neurological impairment appearing immediately after birth resulting from suspected asphyxia with one or more of the following presentations: low Apgar score (< 7), seizures and reduced tone, decreased reflexes, depressed respiratory effort or decreased level of consciousness.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (approval number 5345–18-SMC).

Statistical analysis

The normality of the data was tested using the Shapiro‒Wilk or Kolmogorov‒Smirnov tests. Continuous variables are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), and categorical variables are presented as numbers (%). Comparisons between unrelated variables were conducted with Student's t test or the Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. The chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used for comparisons between categorical variables. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS v.25; IBM Corporation Inc., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

During the study period, there were 121,435 singleton births at our center, 1158 of which were postnatally diagnosed with a TKUC, yielding an incidence of 0.95%. Four cases of pregnancy termination and 4 cases of twin pregnancy were excluded, leaving 1150 cases available for analysis. The Active Management group included 59 patients, and the Routine Management group included 1091 patients. The median gestational age at the time of knot detection was 23 4/7 weeks (IQR 22–30 6/7). Over one-third (39%) of the cases were detected on a targeted scan for various anomalies or conditions, such as FGR, single umbilical artery, placenta accreta, previous IUFD, NRFHR, liver calcifications, increased HCG, echogenic bowel, aortic stenosis, genetic abnormality, placental abruption and placental lesions, while the rest were detected on routine anomaly or biophysical scans. Table 1 displays a comparison of background characteristics of the groups. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups regarding maternal age and BMI, rates of nulliparity, previous CS or trial of labor after TOLAC.

Perinatal adverse outcome

A comparison of the perinatal outcomes of the entire cohort is presented in Table 2. Both groups demonstrated a similar rate of composite asphyxia-related outcome (16.9% vs 16.8%, p = 0.97). There were no statistically significant differences detected in the individual perinatal outcomes between the groups, except for MSAF, which was lower in the active management group (1.7% vs 18%, p < 0.001), and NICU admissions, especially prematurity-related NICU admissions, which were greater in the active management group (13.6% vs 3%, p < 0.001 and 8.5% vs 1.7%, p = 0.005, respectively). Fetal death occurred exclusively in the Routine Management group (1.8%, 20/1091), but this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.62).

As expected, the Active Management group delivered earlier and at lower median birthweights than did the Routine Management group (37 1/7 vs 39 2/7 weeks of gestation, 2822 g versus 3260 g, p < 0.0001, for both). There was a higher rate of prematurity (27.1% vs 5.3%, p < 0.001) and induced prematurity (81.3% vs 31.6%, p < 0.001) in the Active Management group. There was a similar dispersion of iatrogenic prematurity indication, with most cases induced for maternal/fetal distress in both groups (72.2% vs 61.5%, p 0.7%).

Clinical significance of meconium-stained amniotic fluid

The rate of MSAF was found to be significantly lower in the active management group. Since both fetal distress and advanced gestational age at the time of delivery are known to be associated with MSAF [18], collinearity was suspected. Binary logistic regression was performed and included the following variables: gestational age at the time of delivery, study group assignment (Active/Routine Management) and NRFHR. Of these, only gestational age at delivery and NRFHR were found to be independently associated with MSAF in the current cohort.

Delivery outcomes

Delivery outcomes are presented in Table 3. Significant differences were found regarding the mode of delivery between the groups. There was a higher rate of CS and a lower rate of normal vaginal delivery in the Active than in the Routine Management group (37.3% vs 19.2% and 55.9% vs 74.4%, respectively, p = 0.003). There was a higher rate of primary CS without trial of labor (TOL) in the Active Management group (27.1% vs 11%, p < 0.0001). Accordingly, there was a lower rate of TOL in the Active Management group (72.9% vs 89%, p < 0.0001).

Among patients attempting TOL, there were similar rates of vaginal deliveries (86% vs 90.8%, p = 0.3), including spontaneous vaginal deliveries (76.7% vs 83.6%, p = 0.48). Notably, the Active Management group presented a nonsignificant trend toward lower rates of CS due to NRFHR and of CS/instrumental vaginal delivery due to NRFHR than did the Routine Management group (0% vs 6.1%, p = 0.17 and 4.7% vs 12.2%, p = 0.14).

Fetal death characteristics

The characteristics of the 20 cases o fetal death are presented in Table 4. The median and interquartile range of gestational age at fetal death was 36.5 5/7 weeks (33–38 2/7). Half of the fetal deaths occurred at term, and 95% (19/20) occurred after 30 weeks of gestation. A quarter of the fetuses were growth restricted, significantly more than among TKUC survivors (25% vs 6.8%, p = 0.01). Fetal well-being assessment, including FHRM and biophysical profile, was performed in half of the fetal death cases in the preceding week. A reassuring fetal status was determined in 90% (9/10) of the fetal death cases assessed by FHRM. One case of fetal death was preceded by recurrent moderate decelerations on FHRM. Despite an emergency CS, the fetus was stillborn and did not respond to cardio-respiratory resuscitation.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the benefit of active management of prenatally detected TKUC, consisting of weekly fetal monitoring from 30 weeks and labor induction between 36 and 37 weeks. Previous studies have investigated other aspects of TKUC, including associated risk factors, perinatal outcomes and prenatal detection [1,2,3,4, 7,8,9, 11, 13,14,15, 19,20,21,22,23]. TKUC was found to be associated with fetal death [1,2,3, 7, 8], NRFHR [3, 7, 9], CS due to NRFHR [1, 7, 9, 10], low Apgar score [2, 8, 10], and meconium-stained amniotic fluid [3, 10]. The principal findings of the current study are that active management of TKUC confers a comparable rate of composite asphyxia-related outcome to that of routine management. Furthermore, active management in its current form is associated with increased rates of CS, labor induction, prematurity, induced prematurity, and NICU admissions, especially due to prematurity. These findings question the justification of active management in its current form.

The main purpose of active management is to prevent fetal death and asphyxia. Although rare, it has been shown by Weissmann-Brenner et al. to be more common in pregnancies affected by TKUC, with a tenfold increased risk of fetal death from 37 weeks of gestation compared to the general fetal population, reaching 1% at term [1]. In accordance with this study, half of the fetal deaths in the current study occurred at term, supporting the rationale for labor induction at 37 weeks as a preventative measure. The fact that all fetal deaths occurred exclusively in the Routine Management group implies that active management may prove to be beneficial; however, a larger cohort is needed to statistically confirm this observation.

The benefit of weekly fetal well-being assessment is questionable since fetal death seems to be acute and unpredictable. In the present study, fetal death occurred within a week of a reassuring fetal assessment in nearly half of the patients, implying that FHRM is ineffective for predicting fetal death in TKUC. Moreover, intrapartum FHRM has been shown to be unaffected by TKUC, presenting similar FHRM patterns in pregnancies with and without TKUC [2, 21]. Therefore, the evidence does not support intermittent FHRM as an effective measure for preventing fetal death.

Interestingly, our study revealed a lower rate of MSAF in the active management group. Previous studies have shown higher rates of MSAF in patients with TKUC than in controls. MSAF has been proven to be associated with both fetal distress and advanced gestational age [18]. Similarly, multiple regression in the current study revealed that MSAF was independently associated with both gestational age at delivery and NRFHR but not with active/routine management group assignment. Whether this reduction in MSAF may aid in preventing the rare occurrence of Meconium Aspiration Syndrome should be further assessed in a large cohort. None of the patients in the current study experienced this dire outcome.

Unfortunately, active management appears to have had a negative impact on delivery outcomes. First, there were fewer attempts at TOL, lower rates of vaginal delivery and higher rates of primary CS, without a trial of labor. This may be partially due to maternal anxiety caused by the knowledge of an existing TKUC, as reflected in the nonsignificant trend of a higher rate of CS at maternal request. The effect of maternal anxiety in TKUC on the choice of CS as a mode of delivery was also described in a previous study by Bohiltea et al. [9]. In addition to maternal anxiety, patients in the Active Management group with a history of a single CS might have chosen an elective re-CS instead of attempting labor induction to avoid uterine rupture [24, 25]. Nevertheless, our data show that patients receiving active management and attempting TOL had equally high rates of successful vaginal deliveries as patients receiving routine management (86% vs 90.8%, p 0.3). Therefore, patients with prenatally detected TKUC should be encouraged to attempt TOL. Patients with a history of a single low segment CS should be counselled on the risk of uterine rupture during labor induction in TOLAC which has been shown to be slightly increased compared to spontaneous labor in TOLAC [26, 27].

A second disadvantage of active management was the increased rate of prematurity, especially induced prematurity, which led to increased rates of adverse neonatal outcomes, including increased NICU admissions due to prematurity. Fortunately, some cases of induced prematurity can be prevented by avoiding preterm labor induction due to TKUC in the presence of reassuring fetal well-being, as occurred in 30.8% of the cases of induced preterm birth in the current study. This approach is supported by the observation of Weissmann-Brenner et al. of a tenfold increased risk of fetal death from 37 weeks of gestation in TKUC compared to the general fetal population. Before term, there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of fetal death [1].

The clinical value of routinely scanning the entire length of the umbilical cord is questionable. This depends on the benefit of an intervention to prevent fetal death and asphyxia associated with TKUC. Currently, there is no evidence to support this practice. Should a sufficiently powered study prove an advantage for some form of active management, then a routine scan of the umbilical cord would be justified. The current study presents preliminary data to support a larger future study. Technically, scanning the entire length of the cord at mid-trimester has been shown to be feasible with an accuracy of 96.4% [15].

The current study is not without limitations. First, due to the relatively small number of prenatally detected knots and the rarity of fetal deaths, this study was underpowered to evaluate this outcome. At least 300 active management cases are needed to prove a statistically significant difference in fetal death at a power of 80%. Furthermore, a larger cohort might reveal other statistically significant differences, which in the current study appear as trends, such as a lower rate of NRFHR and CS due to NRFHR. Second, the retrospective design of the study has inherent methodological flaws, including a selection bias of high-risk patients in the Active Management group, who were more frequently scanned for various indications, facilitating the detection of TKUC in this population. Another inherent limitation of the retrospective design was the nonuniform management of both groups, since department policy slightly evolved over the 11-year period of the study. For example, in earlier years, patients diagnosed with TKUC were induced at 36 weeks, and over the years, induction was postponed to 37 weeks. Ideally, in order to optimally evaluate the benefit of active management in TKUC, a randomized control trial randomizing patients with a prenatally detected TKUC to routine and active management should be performed. However, considering the evidence of increased fetal death [2,3,4, 7, 8], especially at term [1], it may be regarded unethical and pose legal risks to intentionally provide routine management in pregnancies with a known TKUC.

This study has several strengths worth mentioning. First, this is a novel study evaluating the impact of active management in TKUC, a subject that has never been studied before. Second, the study comprises the largest cohort of prenatally diagnosed TKUCs in the published literature, offering insights that may improve the perinatal outcome in pregnancies diagnosed with a TKUC, such as avoiding unnecessary induced prematurity and unindicated CS.

To conclude, compared with routine management, weekly FHRM and labor induction at 36–37 weeks in patients with TKUC do not appear to reduce neonatal asphyxia. In its current form, active management is associated with higher rates of cesarean deliveries, induced prematurity, and NICU admissions. Based on these observations, labor induction before 37 weeks should be avoided. In the absence of a contraindication, patients can be encouraged to attempt vaginal delivery. Although there is a certain indication that active management may reduce fetal death a larger cohort is needed to determine a true advantage.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Weissmann-Brenner A, Meyer R, Domniz N, Levin G, Hendin N, Yoeli-Ullman R, Mazaki-Tovi S, Weissbach T, Kassif E (2022) The perils of true knot of the umbilical cord: antepartum, intrapartum and postpartum complications and clinical implications. Arch Gynecol Obstet 305:573–579

Airas U, Heinonen S (2002) Clinical significance of true umbilical knots: a population-based analysis. Am J Perinatol 19:127–132

Hershkovitz R, Silberstein T, Sheiner E, Shoham-Vardi I, Holcberg G, Katz M, Mazor M (2001) Risk factors associated with true knots of the umbilical cord. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 98:36–39

Hayes DJL, Warland J, Parast MM, Bendon RW, Hasegawa J, Banks J, Clapham L, Heazell AEP (2020) Umbilical cord characteristics and their association with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 15:e0239630

Collins JH (1991) First report: prenatal diagnosis of a true knot. Am J Obstet Gynecol 165:1898

Lichtman Y, Wainstock T, Walfisch A, Sheiner E (2020) The significance of true knot of the umbilical cord in long-term offspring neurological health. J Clin Med 10:123

Agarwal I, Singh S (2022) Adverse perinatal outcomes of true knot of the umbilical cord: A case series and review of literature. Cureus 14:e26992

Gaikwad V, Yalla S, Salvi P (2023) True knot of the umbilical cord and associated adverse perinatal outcomes: a case series. Cureus 15:e35377

Bohiltea RE, Varlas V-N, Dima V, Iordache A-M, Salmen T, Mihai B-M, Bohiltea AT, Vladareanu EM, Ducu I, Grigoriu C (2022) The strategy against iatrogenic prematurity due to true umbilical knot: from prenatal diagnosis challenges to the favorable fetal outcome. J Clin Med 11:818

Houri O, Bercovich O, Wertheimer A, Pardo A, Berezowsky A, Hadar E, Hochberg A (2024) Clinical significance of true umbilical cord knot: a propensity score matching study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 24:59

Sepulveda W, Shennan AH, Bower S, Nicolaidis P, Fisk NM (1995) True knot of the umbilical cord: a difficult prenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 5:106–108

Hasbun J, Alcalde JL, Sepulveda W (2007) Three-dimensional power Doppler sonography in the prenatal diagnosis of a true knot of the umbilical cord: value and limitations. J Ultrasound Med 26:1215–1220

Ramón Y, Cajal CL, Martínez RO (2004) Prenatal diagnosis of true knot of the umbilical cord. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 23:99–100

Sherer DM, Amoabeng O, Dryer AM, Dalloul M (2020) Current perspectives of prenatal sonographic diagnosis and clinical management challenges of true knot of the umbilical cord. Int J Womens Health 12:221–233

Weissmann-Brenner A, Domniz N, Weissbach T, Mazaki-Tovi S, Achiron R, Weisz B, Kassif E (2020) antenatal detection of true knot in the umbilical cord - how accurate can we be? Ultraschall Med 43(3):298–303

Macones GA, Hankins GDV, Spong CY, Hauth J, Moore T (2008) The 2008 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop report on electronic fetal monitoring: update on definitions, interpretation, and research guidelines. Obstet Gynecol 112:661–666

Executive summary: Neonatal encephalopathy and neurologic outcome, second edition. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy (2014) Obstet. Gynecol 123:896–901

Gallo DM, Romero R, Bosco M, Gotsch F, Jaiman S, Jung E, Suksai M, Ramón Y, Cajal CL, Yoon BH, Chaiworapongsa T (2023) Meconium-stained amniotic fluid. Am J Obstet Gynecol 228:S1158–S1178

Ippolito DL, Bergstrom JE, Lutgendorf MA, Flood-Nichols SK, Magann EF (2014) A systematic review of amniotic fluid assessments in twin pregnancies. J Ultrasound Med 33:1353–1364

Linde LE, Rasmussen S, Kessler J, Ebbing C (2018) Extreme umbilical cord lengths, cord knot and entanglement: Risk factors and risk of adverse outcomes, a population-based study. PLoS ONE 13:e0194814

Carter EB, Chu CS, Thompson Z, Tuuli MG, Macones GA, Cahill AG (2018) True knot at the time of delivery: electronic fetal monitoring characteristics and neonatal outcomes. J Perinatol 38:1620–1624

Guzikowski W, Kowalczyk D, Więcek J (2014) Diagnosis of true umbilical cord knot. Arch Med Sci 10:91–95

Singh C, Kotoch K (2020) Prenatal diagnosis of true knot of the umbilical cord. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 42:1065–1066

Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Leindecker S, Varner MW, Moawad AH, Caritis SN, Harper M, Wapner RJ et al (2004) Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 351:2581–2589

Macones GA, Peipert J, Nelson DB, Odibo A, Stevens EJ, Stamilio DM, Pare E, Elovitz M, Sciscione A, Sammel MD et al (2005) Maternal complications with vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: a multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 193:1656–1662

Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Martin DP (2001) Risk of uterine rupture during labor among women with a prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 345:3–8

Kehl S, Weiss C, Rath W (2016) Balloon catheters for induction of labor at term after previous cesarean section: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 204:44–50

Funding

Open access funding provided by Tel Aviv University. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Yonatan Back, Shir Lev, Abeer Massarwa, Raanan Meyer, Tal Elkan Miller, Eran Kassif and Tal Weissbach. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Tal Weissbach and Eran Kassif and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.”

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare to have fulfilled the following roles in the conduct of the study and composing of the manuscript. Tal Weissbach: Protocol/project development, Writing—Original Draft, Data collection or management, Data analysis. Yonatan Back: Writing—Review & Editing, Data collection or management. Shir Lev: Writing—Review & Editing, Data collection or management. Abeer Massarwa: Writing—Review & Editing, Data collection or management. Raanan Meyer: Writing—Review & Editing, Resources, Data analysis. Tal Elkan Miller: Writing—Review & Editing, Data collection or management. Boaz Weisz: Writing—Review & Editing, Protocol development. Alina Weissmann-Brenner: Protocol development, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. Shali Mazaki-Tovi: Protocol development, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. Eran Kassif: Protocol/project development, Writing—Original Draft, Data analysis.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weissbach, T., Lev, S., Back, Y. et al. The benefit of active management in true knot of the umbilical cord: a retrospective study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 310, 337–344 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-024-07568-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-024-07568-1