Abstract

Purpose

Emergency training using simulation is a method to increase patient safety in the delivery room. The effect of individual training concepts is critically discussed and requires evaluation. A possible influence factor of success can be the perceived reality of the participants. The objective of this study was to investigate whether the presence in a simulated emergency caesarean section improves subjective effect of the training and evaluation.

Methods

In this observation study, professionals took part in simulated emergency caesarean sections to improve workflow and non-technical skills. Presence was measured by means of a validated questionnaire, effects and evaluation by means of a newly created questionnaire directly after the training. Primary outcome was a correlation between presence and assumed effect of training and evaluation.

Results

106 participants (70% of course participants) answered the questionnaires. Reliability of the presence scale was good (Cronbach’s alpha 0.72). The presence correlated significantly with all evaluated items of non-technical skills and evaluation of the course. The factor “mutual support” showed a high effect size (0.639), the overall evaluation of the course (0.395) and the willingness to participate again (0.350) a medium effect. There were no differences between the professional groups.

Conclusion

The presence correlates with the assumed training objectives and evaluation of the course. If training is not successful, it is one factor that needs to be improved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Reducing maternal and neonatal mortality is a global effort for years [1, 2]. Meanwhile, the concept of “maternal near miss morbidity” is being pursued, which includes the period around birth in the observation period [3]. Analogous to other areas of healthcare, the working circumstances of obstetrics fulfil the framework of a high responsibility team (HRT). Death as a result of decisions made, the irreversibility of many therapeutic decisions and time pressure are some characteristics of this work environment [4]. Like in aviation settings, better training of emergencies has been a widespread recommendation [1, 2] and simulation trainings with technical and non-technical contents were implemented [5]. However, success has not always been proven and the content and structure of trainings is debated [6]. Draycott et al. testify, that training is expensive, therefore if training is done, it should be ‘effective training’. This means a reduction in mortality and morbidity and improved outcomes [7].

Evaluation of training and its impact in the patient care can be difficult, especially when it comes to identify success factors. Team composition, training location, didactics and content vary between the studies and complicate the comparability. For example, the debriefing of scenarios is recognized as the most important feature of simulation-based medical education [8] and is not always described methodically.

In this study, we focused on the relevance of perceived reality of the participant. For the description of the participant’s perceived reality, a wide range of different terms and scoring systems are used. Fiction contract [9] and immersion [10] are some examples. In our study, we used the “Presence Scale for Lab-based Microworld Research” (PLBMR), which is available in a German language validated form [11] and adapted to the health care context [12].

Even though studies found positive correlations between perceived degree of reality and learning outcomes [13, 14], we have not yet found any correlation between presence and changes in the willingness of participants to work in teams [15]. However, learning non-technical and technical skills could be different on presence.

The aim of the study was to assess the impact of presence on the subjective training value to the participant in an emergency caesarean section training. The used simulation course for this purpose was already established [16] and was successfully tested positively for transfer to everyday clinical practice [17].

The results are used, to value presence as a quality marker for simulation scenarios to integrate them into a corresponding course. Our hypotheses were: the scales of PLBMR are applicable for a German inter-professional delivery room team (a), different professional groups rate the training differently (b), the presence correlates with the subjective effect on non-technical skills (c), the presence correlates with the evaluation of the course in regard to significance for daily work (d), overall evaluation (e), and willingness to participate the training again (f).

Methods

The study was designed as a retrospective study using survey methodology with participants from an emergency caesarean section training program (HAINS Safety simulation program). The measurements were taken immediately after the training course. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Hannover Medical School (no. 7511) and financed exclusively from departmental funds.

Setting and population

The participants were professionals of a university hospital (tertiary referral centre). In the year before the training, 2982 childbirth were recorded, of which 919 were caesarean sections, 54 were emergency caesarean sections. Up to the training, there were training events by means of lectures and separated practical exercises of technical skills. Participation in the questionnaire study was voluntary and could be terminated at any time without giving reasons. The setting has already been described an devaluated in another context with regard to subjective competence gain [16] and transfer of the training content into everyday clinical practice [17]. Participation in the training was planned and specified by the supervisors. In total, 25 theatre nurses, 31 midwives, 23 obstetricians, 46 anaesthetic nurses and 26 anaesthesiologists (in total 151 participants). At last, 80% of the delivery room staff of each department was trained. No other simulation trainings were performed before and during the study.

Training course

The intervention was scheduled as a 4 h simulation-based emergency caesarean section training in an inter-professional team with all involved professional groups [18]. The training goals were to train the department-specific standard operation procedure of an emergency caesarean section and to improve non-technical skills. In the context of these objectives, it was possible to train in the simulation center, unlike training in process flows [19]. The availability of an audio–video debriefing facility and the possibility of normal clinical care in the delivery room were further arguments. Neonatal care was not included in the scenarios because, in the experience of the trainers, the scenarios become too long and complex. After an introductory lecture, each participant has the opportunity to take part in two scenarios actively and in two scenarios as an observer. The scenarios included the care of the mother in the delivery room, the decision to perform an emergency caesarean section, alerting the operation team, transfer of the patient to the operation room, induction of a general anaesthesia and skin incision. All scenarios were recorded on video and a debriefing according “TeamGAINS” methodology [20] was conducted.

Questionnaire

Presence

The scale “Presence Scale for Lab-based Microworld Research” (PLBMR) was devised by Frank and Kluge [11]. All six items of the questionnaire were rated in a 6-point Likert scale from 1 = “totally disagree” to 6 = “totally agree” (Table 1). The internal consistency of the scale proved to be alpha = 0.71 [11]. The mean of all items is used as a marker for the presence during the simulated scenarios (one item is used reverse-scored).

Evaluation of the course by the participants

In the work environment of the study participants, it cannot be assumed that the terms around the research of non-technical skills are known. To assess the impact of the training, authors therefore chose terms which, in their experience, are most frequently used by the employees in the context of an emergency caesarean section (6 Items). The questionnaire can be found in the supplement material. The assumed effect of the training should be rated on a Likert-scale of 1 = “strong effect” to 6 = “no effect”. In addition, participants were asked to rate the statement: “I have benefited from the course for my everyday working life” (Likert Scale: 1 = strongly agree to 6 = strongly disagree). To proceed the overall evaluation of the course, the six-point scale of the German school rating system was used, which is considered to be generally known (1 = “very good”–6 = “unsatisfactory”). To assess the participant’s willingness to take part in a future simulation session, a three-point Likert scale was used: 1 = “participate not voluntary” to 3 “gladly participate”.

Statistical analysis

The demographic and survey data were analysed in a descriptive manner. For testing hypothesis (a), the reliability of the scale, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated. The normal distribution was revised using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Differences in the evaluation by the professional groups (hypothesis b) were examined by the Kruskal–Wallis test.

To test hypothesis c-f, whether the presence correlates with rating and subjective effect of the course, a Kendall-Tau-b correlation was calculated. We assumed a p < 0.05 as being statistically significant. The effect size was interpreted according to Cohen as small (> 0.1), medium (0.3–0.5) and high (> 0.5) [21]. All calculations were conducted using SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM Corporation, Forster CITY, CA, USA).

Results

In total, 106 participants completed the questionnaire (70 percent of the course participants). The data are shown by professional group in Table 2.

Reliability of the scale

To test hypothesis (a), Cronbach’s alpha was calculated. The result for the presence questionnaire was 0.72. No item reduction led to a further substantial increase in Cronbach’s alpha.

Rating and evaluation by professional group

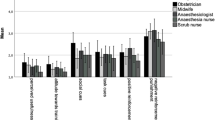

To evaluate the presence, suspected effects on non-technical skills and attitude of the individual to further training (hypothesis b), the arithmetic mean was calculated within each item. The presence was rated mean = 4.76 (SD = 0.78). Values of the suggested effects are shown in Fig. 1. The benefit for the own daily work was evaluated with mean = 1.63 (SD = 0.98). The overall evaluation was rated with mean = 1.63 (SD = 0.87). The willingness to take part in a repetitive training was rated with mean = 2.66 (SD = 0.51).

The results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test showed not normally distributed data. There were no significant differences in the ratings between the professional groups (hypothesis b).

Correlation

The correlation of presence and effects on non-technical skills is shown in Table 3. (hypothesis c). All questioned items showed a significant correlation, with the parameter “mutual support” achieving a high effect, self-reflection and finding solutions a medium effect. The correlation of presence and evaluation of the course is shown in Table 4. “Overall evaluation of the course” and “willingness to participate in another simulation training” showed a medium effect. All three items correlated significantly with the perceived presence (hypothesis d-f).

Discussion

The aim of our study was, to test the assessment of presence in the target group of an inter-professional delivery room team and to describe its effects on the subjective perception of the participants.

Main findings

Reliability of the presence scale

The value of Cronbach’s alpha was 0.72 which is good for low-stakes instruments [22]. Compared to a previous study (Cronbach’s alpha 0.53 (acceptable)) [15], this is a higher value, which is interesting, because the number of professional groups involved in a delivery room training tend to be more. In the comparative study, only two professional groups, anesthetist and anesthesia nurse were involved in an incident training, but they worked in a wide variety of anesthesia departments [15]. Participants´ history, previous social interaction, and past psychological history are known as influence factors on perceived reality [23].

Here, the work environment of the participants seems to have more influence on the reliability of presence than the professional group. Consequentially, scenarios should be adapted to the special needs of the participants in various departments. For delivery room training, for example, an evaluation with professional groups working in different level of cares might be necessary.

Different evaluation of the training by professional group

The argument, that the professional group is not decisive is supported by the fact, that in our study, we did not have any significant differences in all assessments by the professional group (hypothesis b). The scenarios of an emergency caesarean section seem to be equally suitable for all professional groups to generate an equivalent presence.

All evaluation items were rated good (all values above 4.4), which was not surprising as the training had already been evaluated in terms of subjective competence gain [16].

Presence as one success factor for simulation training

The presence correlated significantly with all evaluated items of non-technical skills (hypothesis c). This correlation supports the approach that the perceived reality is correlated to learning as one factor and is in line with this part of the literature [14]. Especially when trainings are ineffective, as discussed in obstetric trainings [6], a lack of presence or similar concepts can provide clues to improve the simulations. This must not be reduced to the use of different simulators—e.g., high versus low fidelity. Furthermore, there are studies that showed the superiority of a low-fidelity simulator [24, 25]. In addition to a physical fidelity, a high psychological fidelity and cognitive fidelity are especially important [26]. To create a high perceived reality of the participants, several conditions have to be met. Availability of expected material, demands for underlying cognition and information processing, disturbing jumps in time and unnatural interaction with the patient are some examples [27]. It is not surprising that the effects were high, as other factors also have influence on the success factors of training courses. In addition to the mentioned debriefing concept, there are additional influence factors like the role of the teacher [28].

Strengths and limitations

This study hast the limitation of having a monocentric design. Training and safety culture of the individual department could influence the willingness to train and thus also the perception of the simulation. Due to the voluntary nature of the study, not all participants took part in the survey and a pre-selection is possible. However, we consider the response rate almost 70% to be almost acceptable. The professional group of anesthesia nurses shows a lower participation. The training was organized so that the anesthesia nurses of the first course (two trainings a day) replaces the colleagues of the second course in the operation theatre. In our opinion, this time, pressure influences the willingness to participate.

Interpretation

Since starting our anesthesia-focused studies, there was no dependence of presence on teamwork [15]. Here the highest correlation of presence is with the item “mutual support”, which can be assigned to the non-technical skill “teamwork” [29]. This aspect is likely increased, the more interdisciplinary and inter-professional groups are involved in the training. The scenarios require procedures, which are not necessarily assigned to one medical specialty (e.g., positioning the patient on the operating table). Even if there is a clear allocation in the standard of the clinic, distractors always occur (e.g., different times of arrival of the team members) and need handling. The perceived reality increases the pressure to act for the participants. The scenarios in anesthesia settings are mostly single-placed. There is no challenge of changing the place of action during urgent medical measures.

The item “improving finding solutions” can be interpreted in line with this argumentation. Based on the as-if-concept, who perceived the effects of the clinical rules (here time pressure during emergency cesarean section), these circumstances influence the item.

It is also understandable for the item “self-reflection”. A participant, as experienced professional, only reviews his own behavior when the observed situation feels real. This interpretation follows the theory that adults learn through a process of working out what possible explanations are and sorting them into probable and less probable, on the basis of reflecting on feedback, on existing experience and knowledge [30].

The item “improving communication” has the lowest correlation with the measured presence. This was not expected, as communication is seen as one of the core-elements of non-technical skills [31]. On the Likert Scale of evaluation, the item reaches the highest level, so other success factors of the course must influence the evaluation of communication improvements.

The trained professional groups meet in everyday practice mainly in clinical care. The course offers a rare opportunity to meet with other professional groups in a protected environment. A positive effect of simulation as a method for teambuilding has been described before [32] and, according to our interpretation, is highly valued in the study group for the item “communication”. The training of standard keywords (e.g., anesthesiologist: “Tube is in-incision!”), may not require high levels of scenario reality. These aspects can be noted as training of processes rather than simulation training.

The evaluation of the items “significance for daily work”, “overall evaluation” and “willingness to participate again” (hypothesis d, e, f) can be classified as level one according to Kirkpatrick [33]. The correlation of presence with these items shows that presence is a factor of reaction and should be subsequently valued. Implementation and compliance of standard operation procedures are challenging and needed continuous efforts over time [34]. Participant´s acceptance and appreciation of the training will be important for the long-term implementation of a training program, as postulated by Draycott et al [7].

Conclusion

The scale of presence is applicable in the professional groups working in a delivery room. The presence correlates with the assumed training objectives and the evaluation of the course. This could be a success factor for the implementation of a continuous training concept. If simulation training is not successful, the perceived reality of participants in the training would be a possible point of improvement. The concept of presence provides an easy-to-use method.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

All code for data cleaning and analysis associated with the current submission are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, Dawson A, Drife J, Garrod D et al (2011) Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006–2008. the eighth report of the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. Int J Obstet Gynaecol 118(Suppl 1):1–203

Mavalankar D, Singh A, Patel SR, Desai A, Singh PV (2009) Saving mothers and newborns through an innovative partnership with private sector obstetricians: chiranjeevi scheme of Gujarat. India Int J Gynaecol Obstet 107(3):271–276

Pattinson R, Say L, Souza JP, Broek N, Rooney C (2009) WHO maternal death and near-miss classifications. Bull World Health Organ 87(10):734

Hagemann V, Kluge A, Ritzmann S (2011) High responsibility teams – a systematic analysis of teamwork contexts for effective competence acquisition. Psychol Everyday Act 4(1):22–42

Gavin NR, Satin AJ (2017) Simulation training in obstetrics. Clin Obstet Gynecol 60(4):802–810

Draycott T (2017) Not all training for obstetric emergencies is equal, or effective. BJOG 124(4):651

Draycott TJ, Collins KJ, Crofts JF, Siassakos D, Winter C, Weiner CP et al (2015) Myths and realities of training in obstetric emergencies. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 29(8):1067–1076

Fanning RM, Gaba DM (2007) The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Healthc 2(2):115–125

Dieckmann P, Gaba D, Rall M (2007) Deepening the theoretical foundations of patient simulation as social practice. Simula Healthc 2(3):183–193

Dede C (2009) Immersive Interfaces for engagement and Learning. Science 323:66–69

Frank B, Kluge A (2014) Development and first validaton of the Presence Scale (PLBMR) for lab-based microrworld research. In: Felnhofer A, Kothgassner OD (eds) Challenging presence: proceedings of the international society for presence research; 15th international conference on presence, vol 2014. Facultas WUV Universitätsverlag, Vienna, Austria, pp. 31-42.

Hagemann V, Herbstreit F, Kehren C, Chittamadathil J, Wolfertz S, Dirkmann D et al (2017) Does teaching non-technical skills to medical students improve those skills and simulated patient outcome? Int J Med Educ 8:101–113

MacLean S, Geddes F, Kelly M, Della P (2019) Realism and presence in simulation: nursing student perceptions and learning outcomes. J Nurs Educ 58(6):330–338

Dede C (2009) Immersive interfaces for engagement and learning. Science 323(5910):66–69

Flentje M, Eismann H, Sieg L, Hagemann V, Friedrich L (2020) Impact of simulator-based crisis resource management training on collective orientation in anaesthesia: pre-post survey study with interprofessional anaesthesia teams. J Med Educ Curric Dev 7:2382120520931773

Flentje M, Schott M, Woltemate AL, Jantzen JP (2017) Interdisciplinary simulation of emergency caesarean section to improve subjective competence. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol 221(5):226–234

Flentje M, Eismann H, Höltje M, Hagemann V, Brodowski L, von Kaisenberg C (2020) Transfer of an interprofessional emergency caesarean section training program: using questionnaire combined with outcome data of newborn. Arch Gynecol Obstet 302(3):585–593

Flentje M, Schott M, Pfützner A, Jantzen JP (2014) Etablierung eines interprofessionellen simulationsgestützten Kreißsaaltrainings. Notfall + Rettungsmed 17(5):379–385

Flentje M, Eismann H, Sieg L, Friedrich L, Breuer G (2018) Simulation as a training method for the professionalization of teams. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 53(1):20–33

Kolbe M, Weiss M, Grote G, Knauth A, Dambach M, Spahn DR et al (2013) TeamGAINS: a tool for structured debriefings for simulation-based team trainings. BMJ Qual Saf 22(7):541–553

Cohen J (1992) A power primer. Psychol Bull 112(1):155–159

Wasserman JD, Bracken BA (2003) Psychometric characteristics of assessment procedures. In: Graham JR, Naglieri JA (eds) Handbook of Psychology, vol 10. John Wiley, USA, pp 43–66

Rudolph JW, Simon R, Raemer DB (2007) Which reality matters? questions on the path to high engagement in healthcare simulation. Simul Healthc 2(3):161–163

Nicolaides M, Theodorou E, Emin EI, Theodoulou I, Andersen N, Lymperopoulos N et al (2020) Team performance training for medical students: low vs high fidelity simulation. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 55:308–315

Roberts F, Cooper K (2019) Effectiveness of high fidelity simulation versus low fidelity simulation on practical/clinical skill development in pre-registration physiotherapy students: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 17(6):1229–1255

Kluge A (2014) The acquisition of knowledge and skills for taskwork and teamwork to control complex technical systems: a cognitive and macroergonomics perspective. Springer, Netherlands

Hagiwara MA, Backlund P, Söderholm HM, Lundberg L, Lebram M, Engström H (2016) Measuring participants’ immersion in healthcare simulation: the development of an instrument. Adv Simul 1(1):17

Terhart E (2011) Has John hattie really found the holy grail of research on teaching? an extended review of visible learning. J Curric Stud 43(3):425–438

Flin R, Patey R, Glavin R, Maran N (2010) Anaesthetists’ non-technical skills. Br J Anaesth 105(1):38–44

Taylor DCM, Hamdy H (2013) Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education AMEE guide no 83. Med Teach 35(11):e1561–e1572

Aebersold M (2016) The history of simulation and its impact on the future. AACN Adv Crit Care 27(1):56–61

Orledge J, Phillips WJ, Murray WB, Lerant A (2012) The use of simulation in healthcare: from systems issues, to team building, to task training, to education and high stakes examinations. Curr Opin Crit Care 18(4):326–332

Kirkpatrick D, Kirkpatrick J (2006) Evaluating training programs: the four levels. Berrett-Koehler, Oakland

Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Breizat AH, Dellinger EP et al (2009) A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med 360(5):491–499

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Departmental funding only.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors listed have contributed sufficiently to the project (MF: conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript; VH: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article; LB: acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript; SP: acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript; KC: acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript. HE: conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript), authorships have been acknowledged appropriately.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Markus Flentje-receives training simulators free of charge for pilot projects from Laerdal Vera Hagemann-none Lars Brodowski-none Spiridon Papageorgiou-none Constantin von Kaisenberg: Chief manager of PROMPT Germany gUH, which promotes training events to reduce complications in obstetrics Hendrik Eismann-none.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Hannover Medical School (no. 7511) at 08/11/2017 (Chair: Professor S. Engeli).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Flentje, M., Hagemann, V., Brodowski, L. et al. Influence of presence in an inter-professional simulation training of the emergency caesarean section: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 305, 1499–1505 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-022-06465-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-022-06465-9