Abstract

Purpose

Despite patients’ widespread use and acceptance of complementary and integrative medicine (IM), few data are available regarding health-care professionals’ current implementation of it in clinical routine. A national survey was conducted to assess gynecologists’ attitudes to and implementation of complementary and integrative treatment approaches.

Methods

The Working Group on Integrative Medicine of the German Society of Gynecological Oncology conducted an online survey in collaboration with the German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (DGGG) in July 2019. A 29-item survey was sent to all DGGG members by email.

Results

Questionnaires from 180 gynecologists were analyzed, of whom 61 were working office-based in private practice and 95 were employed in hospitals. Seventy percent stated that IM concepts are implemented in their routine clinical work. Most physicians reported using IM methods in gynecological oncology. The main indications for IM therapies were fatigue (n = 98), nausea and vomiting (n = 89), climacteric symptoms (n = 87), and sleep disturbances (n = 86). The most commonly recommended methods were exercise therapy (n = 86), mistletoe therapy (n = 78), and phytotherapy (n = 74). Gynecologists offering IM were more often female (P = 0.001), more often had qualifications in anthroposophic medicine (P = 0.005) or naturopathy (P = 0.019), and were more often based in large cities (P = 0.016).

Conclusions

There is strong interest in IM among gynecologists. The availability of evidence-based training in IM is increasing. Integrative therapy approaches are being implemented in clinical routine more and more, and integrative counseling services are present all over Germany. Efforts should focus on extending evidence-based knowledge of IM in both gynecology and gynecological oncology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The overall use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has increased noticeably worldwide in recent years, and evidence on its effectiveness has started to be incorporated into medical treatment guidelines [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The recommendations on the treatment of breast cancer published by the Breast Committee of the Working Group on Gynecological Oncology (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie, AGO) already included complementary methods in 2002. In addition, the German Cancer Society (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, DKG) is developing a guideline for IM that includes various medical professions [7].

Complementary medicine refers to health-care practices that traditionally have not been part of conventional medicine and represent forms of treatment that are used together with conventional medicine. In contrast, alternative medicine refers to non-mainstream practices that are generally not considered standard medical approaches and are used instead of conventional medicine [8,9,10]. According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), integrative medicine (IM) differs from CAM because it combines conventional and complementary treatments in a coordinated way [11]. Neither rejecting conventional therapies nor relying on alternative medicine, IM adopts only those complementary modalities that are supported by the strongest evidence of safety and effectiveness, resulting in a supplementary, holistic approach to oncological treatment [1, 12,13,14]. We therefore prefer to use the term IM instead of CAM.

The Working Group on Integrative Medicine (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Integrative Medizin, AG-IMed) of the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe, DGGG) identifies CAM treatment on the basis of published evidence-based research that is suitable for supplementing the portfolio of conventional medicine [1].

Physicians represent the main providers of IM therapy in Germany [1, 15] and, in contrast to other countries, breast cancer in Germany is treated by onco-gynecologists. Naturopathy, acupuncture, nutritional counseling, homeopathy, and manual therapy/chiropractic are recognized qualifications for physicians in Germany. While naturopathy is used for different and often eclectic treatment approaches internationally [16], it mainly encompasses herbal medicine (also called phytotherapy), hydrotherapy, and mind–body medicine counseling in Germany [17]. While not a recognized qualification for physicians, anthroposophic medicine is commonly used by German physicians. This medical system is based on a specific organismic concept and uses drugs derived from herbal, mineral, and animal sources, eurythmy (a specific movement therapy), art therapy, rhythmical massage, and lifestyle recommendations [18] (Supplementary digital file 2). No formal qualification is mandatory to practice IM in Germany.

Previous studies on IM use have mainly focused on oncological patients’ motivation, objectives, information sources, and characteristics [19,20,21,22,23,24]. However, little is known about the acceptance and use of IM by gynecological oncologists and general gynecologists throughout Germany [19, 25]. While patients often request IM, many physicians and other caregivers are hesitant to apply any IM methods, especially in a curative setting. A study conducted by Furlow et al., surveyed 401 obstetrics/gynecology physicians in the state of Michigan. Physicians appeared to have a positive attitude toward IM and the majority indicated that they had referred patients for at least one IM modality. Around 73.2% of physicians stated that IM includes areas and methods from which conventional medicine could benefit [26]. The modalities that were most commonly regarded as being highly or moderately effective were biofeedback, chiropractic, acupuncture, meditation, and hypnosis/guided imagery. Physicians (83%) indicated that they routinely ask their patients about IM use [26]. However, the majority of patients did not consult their health-care provider before initiating an IM method elsewhere. The reason for this given by patients was that their physicians never asked them about the use of IM [26]. There is an obvious discrepancy, possibly due to physicians’ time constraints and/or lack of reimbursement for IM. A recent study by Hack et al. confirmed that aspects of IM still very rarely form part of oncological consultations, and this in turn discourages patients. IM programs in comprehensive cancer centers might solve such problems [27].

The aim of this cross-sectional study was to evaluate the current state of attitudes toward IM and patterns of IM provision by office-based as well as hospital-based physicians throughout Germany. Further characteristics such as age, gender, duration of professional work, and experience of physicians perceiving IM as effective were also analyzed. In addition, indications for IM use, competences, structures, implementation, and qualifications, as well as the patients’ expectations (as perceived by the gynecologists) were assessed. Finally, the financial reimbursement provided for IM therapies in daily routine was analyzed. The data collected represent the current situation in the provision of IM by gynecologists in Germany.

Materials and methods

The Working Group on Integrative Medicine of the German Society of Gynecological Oncology (IMed) conducted an online survey in collaboration with the DGGG. The IMed Committee was founded on June 28, 2013. This group of gynecological oncologists focuses on the clinical, scientific, and organizational aspects of IM in oncology. It supports scientific research and cooperation in the field of IM and also encourages the implementation of evidence-based integrative therapy approaches and regular IM consultation hours, to integrate these into standard oncological care [19].

In July 2019, a self-administered, 29-item online survey was sent to all members of the DGGG. The email was sent on July 17th, and a reminder email was not sent. Participation was voluntary and anonymous.

The survey contained 15 multiple-choice questions, including items on the use of integrative therapy methods, fields of indications, counseling services, level of specific qualifications, etc., as well as 14 sociodemographic questions. Questions were designed with a multiple-choice entry format, with single or multiple answers. Missing values were allowed. However, in cases of suspected duplication or when values were missing in all questionnaire items, these questionnaires were deemed unsatisfactory and excluded (Fig. 1). The online platform “SoSci Survey” ensured data transmission at any time in accordance with the current state of technology, and study participants were determined using unique visitors by generating a code with regard to name and date of birth at the start of the survey. The time needed to complete the survey was approximately 12 min. Explanations of terms with regard to the topic of integrative and complementary medicine can be found in Supplementary digital file 2.

The study protocol was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was obtained from the Hamburg Medical Association (reference number Hamburg PV5847). Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to participation in the study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation consisted of descriptive analysis. Total amounts and percentages were calculated. Patients with missing values were excluded from the analysis of the corresponding variables. Student’s independent t tests were used to assess differences in age and years of professional experience between physicians who were providing and not providing IM methods. Differences in categorical variables between physicians providing and not providing IM methods were tested using chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The level of significance was set at < 0.05. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 24.0.0.2 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

A total of 205 questionnaires were returned, 25 of which were excluded from the evaluation either because of suspected duplication or because values were missing in all questionnaire items. Details on evaluable questionnaires are provided in the flow chart (Fig. 1). In all, 180 gynecologists completed the survey, with 102 women (57%) and 48 men (27%). Thirty participants (17%) gave no details on their gender. The respondents’ age ranged from 20 to 74 years (median 43 years). A total of 101/180 gynecologists (56%) had at least a doctoral degree (Table 1).

Among the participants surveyed, 146 (81%) stated that they provided IM approaches in clinical practice. Gynecologists offering IM were more often female, more often had qualifications in anthroposophic medicine or naturopathy, and were more often based in large cities than those who did not offer IM (Table 1). Sixty-five percent of the female gynecologists surveyed provided IM, in comparison with 17% of the male gynecologists surveyed (Table 1).

Sixty-one out of 180 gynecologists worked in private office practices and 95 were employed in hospitals. Three participants stated that they worked both in an office practice and a hospital, and nine participants stated they were neither office-based nor hospital-based; 77/180 (43%) worked in certified breast cancers centers and 61/180 (34%) in certified gynecological oncology centers (Table 1). Most of the gynecologists surveyed were already specialists and had been working for a mean of 14.9 years.

With regard to regional differences, it was found that most participants surveyed were from the state of North Rhine–Westphalia (n = 22, 12%) in western Germany; Bavaria (n = 20, 11%) in southern Germany; and Schleswig–Holstein (n = 13, 7%) in northern Germany (Fig. 2).

Seventy percent of the gynecologists surveyed (n = 94) providing IM (n = 134, 12 missing) stated that they had implemented IM in their routine clinical work, versus 25% (n = 34) who did not include it in the clinical routine and 5% (n = 6) who did not provide any information on the issue. Participants who had established routine IM procedures had been offering these procedures for an average of 10.9 ± 8.7 years. Ninety-five gynecologists (71%) stated that they routinely informed their patients about IM treatment approaches at any time during diagnosis and treatment, whereas 30/134 (22%) started counseling only if patients asked for it, and three participants (2%) stated that they only discussed IM options if conventional medical methods had been insufficient or had failed. Only 5% (n = 6) did not provide any further information (data not shown in a table).

Counseling on applicable IM therapies was mainly provided by the gynecologists themselves (n = 130); by collaborating partners such as other hospitals, clinics, or nonmedical practitioners (n = 43); or by breast care nurses (n = 41) (Table 2). The additional qualifications most often held by those providing IM counseling were naturopathy (n = 63), acupuncture (n = 46), and anthroposophic medicine (n = 39) (Table 2).

Most providers of IM therapy treatments 83/134 (62%) estimated that counseling was not cost-effective, 15% (n = 20) considered that IM counseling would be cost-neutral, and 23% (n = 31) did not supply this information (data not shown in a table).

Participants were also asked to rate the fields in which, and for which problems, IM was a reasonable treatment option in gynecology and gynecological oncology. The results are presented in Table 3. For gynecological complaints such as climacteric symptoms (n = 102), premenstrual syndrome (n = 80), hormonal dysregulation (n = 79), and urinary tract infection (n = 75), IM therapies are most commonly regarded as a reasonable option. By contrast, polycystic ovary syndrome (n = 43), infertility (n = 42), and incontinence (n = 38) were thought by most participants to have less relevance as possible indications for IM (Table 3).

Most of the gynecologists surveyed (n = 113) reported that they used IM therapy methods in the field of gynecological oncology in patients with breast cancer (n = 112), ovarian cancer (n = 93), cervical cancer (n = 62), endometrial cancer (n = 79), peritoneal and Fallopian tube cancer (n = 72), and vulvar/vaginal carcinoma (n = 66) (data not shown in a table). The main indications for IM therapies were fatigue (n = 98), nausea and vomiting (n = 89), climacteric symptoms (n = 87), sleep disturbances (n = 68), and psychological complaints such as anxiety and depression (Table 3). Complementary, the Supplementary digital file 3 displays integrative therapies used during and after breast cancer treatment, with levels of evidence on complementary medicine while breast cancer is the area in which most research of this kind has been carried out.

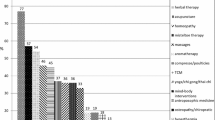

The most commonly recommended methods in the field of general gynecology, such as phytotherapy (n = 81), exercise therapy (n = 76), and food supplements (n = 66), are listed in Table 4. The most commonly recommended IM methods in the field of gynecologic oncology were exercise therapy (n = 86), mistletoe therapy (n = 78), and phytotherapy (n = 74) (Table 4).

Most physicians used IM during chemotherapy (n = 100), hormone therapy (n = 98), and aftercare/follow-up (n = 92) (Supplementary digital file 4).

Last but not least, the gynecologists were asked about their patients’ expectations of IM. IM providers reported their patients’ leading expectations to be an improvement in the quality of life (n = 119), followed by the wish to have holistic treatment (n = 98) and the strengthening of their immune system (n = 96) (Table 5).

Discussion

This national survey represents an attempt to describe attitudes toward IM and patterns of IM provision by office-based as well as hospital-based gynecologists and gynecological oncologists, most likely the main providers of IM for gynecological cancer patients. Little has so far been known about current gynecological providers’ characteristics, as well as their attitudes and user behavior in Germany. So far, professional integrative counseling and therapy concepts have rarely been available in hospitals in Germany and are often limited to a few selected breast cancer centers and specialized hospitals for IM [28]. As it has now been shown by several published studies that gynecological patients are in favor of IM, the evaluation of IM supply by health professionals in Germany is a matter of major interest.

The Working Group on Integrative Medicine of the German Society of Gynecological Oncology earlier developed a questionnaire for gynecological oncologists to evaluate the degree of acceptance, usage, and implementation of IM. The questionnaire was successfully distributed in 2014 to all members of the German Society of Gynecological Oncology in the German Cancer Society (DKG), with a focus on gynecological oncologists working in hospitals [7, 19]. The study showed that there is considerable interest in IM among gynecological oncologists, but that IM therapy approaches were poorly implemented in routine clinical work (25%). However, 64.7% of the gynecological oncologists were planning to do so [19]. In addition, although not routinely, 93% reported that they use IM therapy methods with breast cancer patients and 80% that they use them with ovarian cancer patients. IM providers tended to be male (67.3%) rather than female (32.7%), and 76% were working in certified breast cancer centers.

When the present data are compared with the data from the 2015 survey—as a follow-up study after 5 years—it is evident that 81% of the participants surveyed were providers (vs. non-providers) of IM; 70% were implementing IM in their routine clinical work, and tended to be female rather than male (65% vs. 17%). They were also slightly older than in the earlier AGO survey. Most were working in hospitals rather than being office-based, were in certified breast cancer centers in the majority of cases (41% vs. 35%), and were living in larger cities rather than smaller ones (63% vs. 17%). However, only gender and location differed significantly between providers and non-providers.

A similar survey conducted in 1998–1999 by Münstedt et al., including physicians in various medical fields (including gynecologists, both hospital and office-based) found significant differences between IM providers and non-providers with respect to gender (male 56% vs. female 48.3%), age (providers were older than non-providers), and place of work (office-based 73.4%, vs. hospitals 43.2%, vs. university hospitals 34.7%) [15]. In comparison with the previous studies, the present results show that in the past 20 years, IM has been increasingly integrated into cancer care, particularly in hospitals. However, the studies are not fully comparable, as gynecologists were only a subgroup in the earlier analysis.

A study by Huber et al. surveyed the attitudes of young general practitioners in Germany toward IM [29]. The data indicated that experienced older general practitioners had made a shift from primarily disease-centered to more person-centered care [29, 30].

Recent data from 2014 on IM in radiotherapy in Germany showed that for 32.2% of gynecological oncologists, IM is part of routine treatment (not part of it, 57.3%; unknown, 10.5%) and that 22.0% were planning to incorporate it [7]. Like the Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics, the German Society of Radio-Oncology and Radiotherapy (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Radioonkologie, DEGRO) has recently set up a guideline commission for IM, and radiation oncology is a key field in this context [7].

Relative to the different federal states in Germany, it appears that North Rhine–Westphalia, Bavaria, Schleswig–Holstein, Baden-Wurttemberg, and Hamburg are playing a pioneering role in providing integrative counseling in an oncologic setting (Fig. 2). This is not surprising, as one of the best-established naturopathic hospitals in Germany is located in Essen in North Rhine–Westphalia (“Integrative Onkologie KEM/Evangelische Kliniken Essen-Mitte”). Moreover, the south of Germany has historically shown greater interest in naturopathic treatments than the north. However, due to the high demand from patients and increasing training opportunities for gynecologists, IM has now also reached the north. In recent years, many (university) medical centers in the north such as Schleswig–Holstein and Hamburg-Eppendorf, for example, have established qualified counseling units for IM in gynecology—following the south of Germany, where such units have already existed for more than 10 years (e.g., the university medical centers in Erlangen and at the Technical University of Munich). However, it should be borne in mind that North Rhine–Westphalia and Bavaria have the largest populations among Germany’s federal states, and this may have skewed the data.

At best, gynecologists with appropriate training (e.g., by the Working Group on Gynecological Oncology/AGO) and with qualifications can offer integrative oncology care. Less optimally, physicians without evidence-based knowledge may provide counseling on IM therapies.

In contrast to the special curricula that apply in naturopathy or nutrition, for example, with an examination by the regional state medical association, comparable standardized quality and qualifications for IM counseling in oncology, general gynecology, or obstetrics do not exist. However, the Working Group on Integrative Medicine of the German Society of Gynecological Oncology has recently established a certified course in “Integrative Medicine in Oncology” to correct the current shortage and train medical staff in integrative oncology, to enable them to implement certified IM counseling units both hospital-based and office-based settings to meet the high demand and necessary quality for integrative counseling in Germany. In the best cases, additional qualifications are available.

In addition to the shortage of services and qualified medical staff, another potential hazard that is well known in association with integrative counseling is communication difficulties between physicians and patients [19]. Recent data showed that 47–85% of women with breast cancer who used IM did not disclose this use to the doctors treating them [31]. In the field of general gynecology, only 51.8% of women disclosed their use of IM [32, 33]. Moreover, physicians have in the past had little interest in initiating communication about unconventional therapies, with most regarding such a discussion as a poor use of their time [34]. Although patients want counseling on IM therapies from their gynecologists, rather than from friends, media, self-help groups, etc., gynecologists and other physicians complain about a lack of time, concepts, experience, and last but not least a lack of adequate remuneration [1, 19]. Similarly, in this cross-sectional study, most providers of IM (63%) estimated that counseling would be not cost-effective (AGO survey 55%, DEGRO survey 37.8%), and only 15% considered IM counseling to be cost-neutral (DEGRO 9.8%). Future studies could compare the perceived percentage of use and the disclosure of use by physicians and real percentages from patient surveys.

Among the gynecologists providing IM, 71% stated that they informed their patients about IM at various times during diagnosis and treatment, whereas 22% only started counseling if the patients asked about it proactively. Two percent of the participants, however, only started such a conversation if conventional medical methods were insufficient or had failed (data not shown in a table). Although at a far lower level, this is in line with the results reported by Kalder et al. that 40% (vs. 2% today) of gynecologists recommended IM because of the ineffectiveness of conventional therapies, as an expression of helplessness when the limits of conventional treatment options had been reached [1]. However, the motivation for IM should never be desperation, since helpful palliative medical options have been developed in the field of oncology in particular [35].

IM use and counseling in oncology in the present study were mainly present during chemotherapy (AGO 84%, DEGRO 80%), hormone therapy (AGO 60%, DEGRO 46.2%), and aftercare/follow-up (AGO 70%, DEGRO 55.2%), but continued through all phases of treatment (Supplementary digital file 4)—underlining the strong demand from patients in all treatment phases. The reasons for using IM concomitantly with conventional treatment or after primary therapy are mostly not for medical treatment of the disease, but rather as a supportive treatment to eliminate symptoms, reduce side effects, and strengthen the immune system [36]. Other reasons given by patients for using IM include physical and psychological support for the body and general well-being, improving quality of life, relieving chemotherapy-induced symptoms, enhancing the immune system, and even increasing the chances of survival [37, 38].

This again emphasizes, on the one hand, the need for implementation of qualified and certified IM counseling units, and on the other hand the need for interdisciplinary collaboration among physiotherapists, nutritionists, psychologists, office-based gynecologists, general practitioners, and so on. It is surprising that IM counseling services exist without adequate interdisciplinary collaboration to combine services for patients who request them.

Implementation of office-based units is important, since long-term relationships between most gynecologists and patients may offer a deeper basis of trust to enable patients to ask about integrative methods without inhibitions. Regardless of the cancer type, treatment phase, or workplace, IM therapy methods need to be implemented more in official treatment guidelines to promote trust around physicians as well as patients. At the same time, education and training are mandatory to enable physicians to implement these evidence-based IM methods [39]. In addition, IM treatment approaches need to be implemented in routine clinical work to promote adherence to proposed therapies that meet patients’ urgent needs. Remuneration for IM therapies also needs to be discussed by health-care insurance bodies.

The view that there is an urgent need to provide better qualifications and training for providers of IM in gynecology is not new [25]. The increasing numbers of qualifications available in IM appear to be a positive response to this. The main additional qualifications observed in the present cohort were in naturopathic therapy n = 63 (AGO survey 2014, 48.6%), followed by acupuncture at n = 46 (AGO survey 2014, 29.2%) and anthroposophic medicine at n = 39 (AGO survey 2014, 13.9%) (Table 2). These figures are higher than those in a similar survey by Münstedt et al., which was conducted six years earlier but in a different cohort (310 gynecologists and obstetricians from the state of Hesse in Germany). In that study, 14.8%, 6.1%, and 2.6% had received qualifications in acupuncture, naturopathy, and homeopathy, respectively.

To date in 2020, most research concerned the group of breast cancer patients. The most relevant practical skills seem to be exercise therapy, yoga, nutritional counseling, mindfulness-based stress reduction, acupuncture as well as hypnosis. According to existing Level of Evidence A, the recommendation of these skills for physicians might be meaningful (Supplementary digital file 3) [40,41,42]. Besides international guidelines—in Germany for example—the Breast Committee of the Working Group on Gynecological Oncology (AGO) annually updates evidence-based recommendations on complementary therapies (an English version is available as well) [41, 42]. This is in addition to international guidelines. It would therefore be advisable that physicians obtain qualifications in these IM approaches or collaborate with certified providers.

Data on IM are scarce in the field of gynecology. The participants in the present survey mentioned climacteric symptoms, premenstrual syndrome, hormonal dysregulation, urinary tract infections, genital infections, and endometriosis as reasonable indications for IM (Table 3). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of complementary treatments for endometriosis reported that significant pain reduction is obtained with acupuncture in comparison with sham acupuncture [43]. Other complementary interventions studied included exercise, electrotherapy, and yoga. All of these were inconclusive in relation to benefit, but demonstrated a positive trend in the treatment of endometriosis symptoms [43].

The present study is not without limitations. The self-reported nature of the survey means that the data are at risk of responder and recall bias; there is an inherent bias when distributing a survey regarding IM because those who care for the matter tend to respond more than those who do not. Furthermore, since invitations were sent out by email and could have been forwarded to other physicians, a response rate cannot be calculated. It is also unclear whether responders were representative for the population of German gynecologists and onco-gynecologists. Another limitation is the missing answers in some questions. Moreover, most participants were from larger cities, which might also reduce generalizability; however, hospitals and private practices in Germany tend to be located in bigger cities rather than in smaller ones. Last but not least, most of the initiators of this survey work in the field of gynecology, and some work in the field of IM, and thus were not free of inherent preconceptions about the topic of this survey. This most likely did not lead to substantial bias, since data were assessed and analyzed quantitatively rather than qualitatively.

Despite these limitations, it is clear that physicians need to obtain information about the field of IM to provide accurate advice to patients and optimize their care.

Importantly, the representative national sample included in the study means that the findings may be generalized, and as such this study has potential value for German policy-makers, researchers, and health professionals.

Conclusion

There is a high level of interest in IM among both office-based and hospital-based gynecologists. The availability of evidence-based training in IM is growing, and IM therapy approaches are being increasingly implemented in clinical routine work all over Germany. As IM therapies may involve potential hazards, the provision of qualified IM counseling integrated into conventional medicine may be a helpful tool for keeping in touch with patients who might otherwise withdraw from the physicians’ sphere of influence. Efforts should focus on extending evidence-based knowledge and integrating it into official medical guidelines. Physicians have an ethical obligation to optimize the use of resources and implement newly acquired evidence by incorporating evidence-based IM into conventional medicine and counseling patients proactively about evidence-based practices.

Data availability

Detailed data are available on request by email from Dr. Donata Grimm (d.grimm@uke.de and donatakatharina.grimm@uksh.de) and Dr. Carolin Hack (carolin.hack@uk-erlangen.de).

References

Kalder M, Muller T, Fischer D, Muller A, Bader W, Beckmann MW, Brucker C, Hack CC, Hanf V, Hasenburg A, Hein A, Jud S, Kiechle M, Klein E, Paepke D, Rotmann A, Schutz F, Dobos G, Voiss P, Kummel S (2016) A review of integrative medicine in gynaecological oncology. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 76(2):150–155. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-100208

Xue CC, Zhang AL, Lin V, Da Costa C, Story DF (2007) Complementary and alternative medicine use in Australia: a national population-based survey. J Altern Complement Med 13(6):643–650. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2006.6355

Su D, Li L (2011) Trends in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States: 2002–2007. J Health Care Poor Underserved 22(1):296–310. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2011.0002

Hunt KJ, Coelho HF, Wider B, Perry R, Hung SK, Terry R, Ernst E (2010) Complementary and alternative medicine use in England: results from a national survey. Int J Clin Pract 64(11):1496–1502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02484.x

Kemppainen LM, Kemppainen TT, Reippainen JA, Salmenniemi ST, Vuolanto PH (2018) Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Europe: health-related and sociodemographic determinants. Scandinavian J Public Health 46(4):448–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494817733869

Horneber M, Fischer I, Dimeo F, Ruffer JU, Weis J (2012) Cancer-related fatigue: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Deutsches Arzteblatt Int 109(9):161–171. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2012.0161 ((quiz 172))

Kessel KA, Klein E, Hack CC, Combs SE (2018) Complementary medicine in radiation oncology : German health care professionals’ current qualifications and therapeutic methods. Strahlenther Onkol 194(10):904–910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-018-1345-8

Baum M, Ernst E, Lejeune S (2004) Horneber M (2006) Role of complementary and alternative medicine in the care of patients with breast cancer: report of the European Society of Mastology (EUSOMA) Workshop, Florence, Italy. Eur J Cancer 42(12):1702–1710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2006.02.020

Hack CC, Huttner NB, Fasching PA, Beckmann MW (2015) Development and validation of a standardized questionnaire and standardized diary for use in integrative medicine consultations in gynecologic oncology. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 75(4):377–383. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1545850

Witt CM, Balneaves LG, Cardoso MJ, Cohen L, Greenlee H, Johnstone P, Kucuk O, Mailman J, Mao JJ (2017) A comprehensive definition for integrative oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgx012

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: What’s in a name? https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health-integrative. Accessed 23 Jul 2019

Leis AM, Weeks LC, Verhoef MJ (2008) Principles to guide integrative oncology and the development of an evidence base. Curr Oncol 15(Suppl 2):s83-87. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.v15i0.278

Seely DM, Weeks LC, Young S (2012) A systematic review of integrative oncology programs. Curr Oncol 19(6):e436-461. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.19.1182

Explore IM Integrative Medicine (2011) East Meets West: How integrative medicine is changing Health Care. https://exploreim.ucla.edu/health-care/east-meets-west-how-integrative-medicine-is-changing-health-care/. 14 July 2020

Munstedt K, Entezami A, Wartenberg A, Kullmer U (2000) The attitudes of physicians and oncologists towards unconventional cancer therapies (UCT). Eur J Cancer 36(16):2090–2095. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00194-5

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (2019) Naturopathy. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/naturopathy. Accessed 14 Oct 2020

Michalsen A (2019) The nature cure: a doctor’s guide to the science of natural medicine. Viking, New York

Kienle GS, Ben-Arye E, Berger B, Cuadrado Nahum C, Falkenberg T, Kapocs G, Kiene H, Martin D, Wolf U, Szoke H (2019) Contributing to global health: development of a consensus-based whole systems research strategy for anthroposophic medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3706143

Klein E, Beckmann MW, Bader W, Brucker C, Dobos G, Fischer D, Hanf V, Hasenburg A, Jud SM, Kalder M, Kiechle M, Kummel S, Muller A, Muller MT, Paepke D, Rotmann AR, Schutz F, Scharl A, Voiss P, Wallwiener M, Witt C, Hack CC (2017) Gynecologic oncologists’ attitudes and practices relating to integrative medicine: results of a nationwide AGO survey. Arch Gynecol Obstet 296(2):295–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4420-y

Paul M, Davey B, Senf B, Stoll C, Munstedt K, Mucke R, Micke O, Prott FJ, Buentzel J, Hubner J (2013) Patients with advanced cancer and their usage of complementary and alternative medicine. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 139(9):1515–1522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-013-1460-y

Tautz E, Momm F, Hasenburg A, Guethlin C (2012) Use of complementary and alternative medicine in breast cancer patients and their experiences: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer 48(17):3133–3139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.021

Fasching PA, Thiel F, Nicolaisen-Murmann K, Rauh C, Engel J, Lux MP, Beckmann MW, Bani MR (2007) Association of complementary methods with quality of life and life satisfaction in patients with gynecologic and breast malignancies. Support Care Cancer 15(11):1277–1284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-007-0231-1

Vapiwala N, Mick R, Hampshire MK, Metz JM, DeNittis AS (2006) Patient initiation of complementary and alternative medical therapies (CAM) following cancer diagnosis. Cancer J 12(6):467–474. https://doi.org/10.1097/00130404-200611000-00006

Burstein HJ, Gelber S, Guadagnoli E, Weeks JC (1999) Use of alternative medicine by women with early-stage breast cancer. N Eng J Med 340(22):1733–1739. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199906033402206

Munstedt K, Maisch M, Tinneberg HR, Hubner J (2014) Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in obstetrics and gynaecology: a survey of office-based obstetricians and gynaecologists regarding attitudes towards CAM, its provision and cooperation with other CAM providers in the state of Hesse, Germany. Arch Gynecol Obstet 290(6):1133–1139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-014-3315-4

Furlow ML, Patel DA, Sen A, Liu JR (2008) Physician and patient attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine in obstetrics and gynecology. BMC Complement Altern Med 8:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-8-35

Hack CC, Wasner S, Meyer J, Haberle L, Jud S, Hein A, Wunderle M, Emons J, Gass P, Fasching PA, Egloffstein S, Beckmann MW, Lux MP, Loehberg CR (2020) Analysis of Oncological second opinions in a certified university breast and gynecological cancer center in relation to complementary and alternative medicine. Complement Med Res. https://doi.org/10.1159/000508235

Hack CC, Hackl J, Huttner NBM, Langemann H, Schwitulla J, Dietzel-Drentwett S, Fasching PA, Beckmann MW, Theuser AK (2018) Self-reported improvement in side effects and quality of life with integrative medicine in breast cancer patients. Integr Cancer Ther 17(3):941–951. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735418777883

Huber CM, Barth N, Linde K (2020) How young german general practitioners view and use complementary and alternative medicine: a qualitative study. Complement Med Res. https://doi.org/10.1159/000507073

Ostermaier A, Barth N, Schneider A, Linde K (2019) On the edges of medicine—a qualitative study on the function of complementary, alternative, and non-specific therapies in handling therapeutically indeterminate situations. BMC Family Practice 20(1):55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-019-0945-4

Saxe GA, Madlensky L, Kealey S, Wu DP, Freeman KL, Pierce JP (2008) Disclosure to physicians of CAM use by breast cancer patients: findings from the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study. Integr Cancer Ther 7(3):122–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735408323081

Harrigan JT (2011) Patient disclosure of the use of complementary and alternative medicine to their obstetrician/gynaecologist. J Obstet Gynaecol 31(1):59–61. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2010.531303

Von Gruenigen VE, White LJ, Kirven MS, Showalter AL, Hopkins MP, Jenison EL (2001) A comparison of complementary and alternative medicine use by gynecology and gynecologic oncology patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer 11(3):205–209. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1438.2001.01011.x

Gray RE, Fitch M, Greenberg M, Voros P, Douglas MS, Labrecque M, Chart P (1997) Physician perspectives on unconventional cancer therapies. J Palliat Care 13(2):14–21

Gaertner J, Wolf J, Hallek M, Glossmann JP, Voltz R (2011) Standardizing integration of palliative care into comprehensive cancer therapy–a disease specific approach. Support Care Cancer 19(7):1037–1043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1131-y

Akpunar D, Bebis H, Yavan T (2015) Use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with gynecologic cancer: a systematic review. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prevent 16(17):7847–7852. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.17.7847

Swisher EM, Cohn DE, Goff BA, Parham J, Herzog TJ, Rader JS, Mutch DG (2002) Use of complementary and alternative medicine among women with gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol 84(3):363–367. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.2001.6515

von Gruenigen VE, Frasure HE, Jenison EL, Hopkins MP, Gil KM (2006) Longitudinal assessment of quality of life and lifestyle in newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients: the roles of surgery and chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol 103(1):120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.01.059

Muecke R, Paul M, Conrad C, Stoll C, Muenstedt K, Micke O, Prott FJ, Buentzel J, Huebner J (2016) Complementary and alternative medicine in palliative care: a comparison of data from surveys among patients and professionals. Integr Cancer Ther 15(1):10–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735415596423

Greenlee H, DuPont-Reyes MJ, Balneaves LG, Carlson LE, Cohen MR, Deng G, Johnson JA, Mumber M, Seely D, Zick SM, Boyce LM, Tripathy D (2017) Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 67(3):194–232. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21397

Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft DK, AWMF): S3-Leitlinie Früherkennung D, Therapie und Nachsorge des, Mammakarzinoms V (2020). https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/mammakarzinom/

AGO Kommission Mamma (2020) Komplementäre Therapie. https://www.ago-online.de/fileadmin/ago-online/downloads/_leitlinien/kommission_mamma/2020/PDF_DE/2020D%2023_Komplementaermedizin.pdf. Accessed 14 Oct 2020

Mira TAA, Buen MM, Borges MG, Yela DA, Benetti-Pinto CL (2018) Systematic review and meta-analysis of complementary treatments for women with symptomatic endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 143(1):2–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12576

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe, DGGG), the Working Group on Gynecological Oncology (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie, AGO), the Working Group on Integrative Medicine (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Integrative Medizin, AG-IMed), and the Professional Association of Gynecologists in Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania (Berufsverband der Frauenärzte), as well as Dr. Julia Katharina Rothe.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DG: project development and administration, study design, data collection, analysis of data and writing the manuscript (original draft); PV: project development, conceptualization, supporting, reviewing and approving the manuscript; DP: project development, conceptualization. supporting, reviewing and approving the manuscript; JD: project development, conceptualization, methodology, supporting, reviewing, and approving the manuscript; HC: analysis of the data, reviewing and approving the manuscript; SK: project administration, supervision, reviewing and approving the manuscript; MWB: project development, study design, supervision, reviewing and approving the manuscript; LW: study design, supervision, reviewing and approving the manuscript; BS: project administration, supervision, study review, and approving the manuscript; UF: project administration, reviewing and approving the manuscript; MK: project development, study design, reviewing and approving the manuscript; MW: project development, reviewing and approving the manuscript; A-KT: analysis of data, reviewing and approving the manuscript; CCH: project development, study design, data collection, reviewing and approving the manuscript (original draft).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

DG: research support: Greiner Bio-One GmbH; honoraria: Roche, ESOP, Genomic Health, Oncotype, PV: grant: Karl and Veronica Carstens Foundation; consulting role: Novartis; honoraria: Roche, Novartis, Celgene. CCH: honoraria from Roche and Novartis. SK: personal fees: Roche/Gentech, Genomic Health, Novartis, Amgen, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Astra Zeneca, Somatex, MSD, Pfizer, PFM medical, Lilly, Sonoscape, nonfinancial support from Roche, Daiichi Sankyo, Sonoscape, outside the research submitted here. All other authors hereby declare that they had no conflicts of interest in preparing the present manuscript.

Ethical approval

Research involving human participants.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The study protocol was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was obtained from the respective ethics committees (reference number Hamburg PV5847).

Consent for publication

All authors have provided written consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grimm, D., Voiss, P., Paepke, D. et al. Gynecologists’ attitudes toward and use of complementary and integrative medicine approaches: results of a national survey in Germany. Arch Gynecol Obstet 303, 967–980 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05869-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05869-9