Abstract

This work deals with determination of the viscoelasticity coefficient in chiral smectic liquid crystals possessing the helical structure and is the continuation of the work, in which the elasticity coefficient was presented [Phase Transitions 89 (2016) 368]. The measurements have been performed using optical detection in the small deformation limit. The viscosity coefficient was measured on two commercially available pure chiral materials, namely, 4-(n-hexyloxy phenyl)-1-(2-fuethyl butyl) biphenyl-4-carboxylate and 4-(2-methylbutyl) phenyl-4-n-octylbiphenyl-4-carboxylate, and on resulting binary mixture composed from those materials in 50:50 weight ratio. All three liquid crystalline materials exhibit a tilted ferroelectric phase over a reasonably broad temperature range. Each of the two pure liquid crystalline materials have its own disadvantages. However, by design of the binary mixture in definite weight concentration, we tried to improve the behavior and to tune the properties; specifically, the effect of the viscoelastic properties on the mixture composition has been established.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

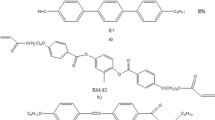

The chiral smectic ferroelectric liquid crystalline (FLC) materials form a very specific by highlighted class of the self-assembling materials with polar ordering which can be used for numerous attractive applications useful for the society needs. Specifically, due to unique properties, the ferroelectric liquid crystals can be effectively used in construction of various optoelectronic devices: light valves, modulators, display devices, and small liquid crystalline displays (Lagerwall 1999; Kuczyński et al. 2000; Kuczyński 2003; Lagerwall and Giesselmann 2006; Bubnov et al. 2008a, 2008b; Lagerwall and Scalia 2012). Application of chiral smectic materials possessing ferroelectric of antiferroelectric polar ordering enables to enhance the switching time, speed of addressing, contrast, information content, and also other parameters of the devices, which are very important for information visualization and control (Rosenblatt et al. 1979; Clark and Lagerwall 1980; Isozaki et al. 1992; Emelyanenko et al. 2006; Jeżewski et al. 2010; Emelyanenko and Ishikawa 2013; Dłubacz et al. 2016;). Since their discovery, a lot of new ferroelectric and antiferroelectric liquid crystalline materials were designed and their properties have been intensively studied (Isozaki et al. 1993; Bubnov et al. 2008a, 2008b; Malik et al. 2010). There are several main tools to reach the desired properties while searching for the materials responding definite demands, for instance, to tune the molecular structure by design on new materials structures, to prepare binary and multicomponent mixtures of structurally similar or structurally different materials (Novotná et al. 2004; Piecek et al. 2010; Modlińska et al. 2011; Bubnov et al. 2016a, 2016b; Emelyanenko 2016), and to prepare nanocomposite materials by doping of the liquid crystalline matrix by various nano-objects like single/multi-wall carbon nanotubes, quantum dots, or different nanoparticles (Fitas et al. 2017; Kurp et al. 2017; Bubnov et al. 2016a, 2016b; Stamatoiu et al. 2011). However, even if the viscoelastic properties are very desirable and important, as they are closely related to the switching time, the available related information for new materials and their mixtures is quite isolated and controversial. The main reason is related to the experimental difficulties, which can occur during the investigations that, in fact, make quite strong contrast with the needs of the research and engineering communities. One of the most significant factors is that the switching time of ferroelectric liquid crystals strongly depends on the mechanical properties, namely, on the rotational viscosity of the smectic c-director. Therefore, the precise determination of this adequate parameter is of great importance for successful design of new optoelectronic applications. Most commonly, the measurements of the viscosity coefficient were done using the switching phenomenon (see, e.g., De Gennes 1974, Takezoe et al. 1984, Lagerwall and Giesselmann 2006, and Marzec et al. 2014). However, this approach might provide incorrect results. The measurement of viscosity is based on the observation of flow caused by an external force. To ensure correctness of the measurements, the flow should be laminar. It is only the case when the flow stimulating factor (in our case the deformation of the helical structure) is weak. For this reason, the switching method can designate only qualitative but not the quantitative results. Up to now, the mechanical properties of the c-director in ferroelectric smectic crystals with non-deformed or weakly deformed helical structure have been unusually investigated (Kuczyński et al. 2009; Dardas et al. 2009). In this work, the electro-optic method has been used for determination of the rotational viscosity coefficient, γ, associated with the smectic c-director in ferroelectric liquid crystalline materials, namely, 4-(n-hexyloxy phenyl)-1-(2-fuethyl butyl) biphenyl-4-carboxylate (denoted here as Ce3) and 4-(2-methylbutyl) phenyl-4-n-octylbiphenyl-4-carboxylate (denoted here as Ce8), and also their binary mixture (denoted here as Ce3/8); this mixture possesses the helical superstructures originating from two ferroelectric liquid crystalline materials with different character of helicoidal behavior. In principle, to apply mixing of different LC materials in order to calibrate and optimize the response time, the dissipation modes and the appropriate laws of mixtures are to be established (Sengupta 2013). In general, it is demanding and not straightforward procedure which involves the dissipative and non-dissipative constitutive equations for nematic liquid crystals (Parodi 1970; Stewart 2004). In fact, from this procedure, the elastic moduli and/or the viscosity coefficients in various mesophases may be inferred. In the present work, an alternative approach is exploited which is based on the dynamic equation for the azimuthal angle and involves the electro-optical method. It is demonstrated that the viscoelastic properties of the binary LC mixtures may be predicted if the viscoelastic properties of the pure compounds are known in advance. It is demonstrated on the example of pure Ce3 material mixed with pure Ce8 material in a 1:1 ratio in this work. The ferroelectric SmC* phase of both materials has a layered structure and a single helicoid in the direction perpendicular to the layer plane. However, probably due to differences resulting mainly from the tilt angle of molecules with respect to the layer normal, one can notice differences in the temperature behavior of the pitch period for both materials. For Ce3 compound, the tilt angle is 45° and does not depend on the temperature; at the N*-SmC* phase transition, the values of tilt angle jump-up, which clearly indicates the first-order phase transition. On contrary for the Ce8 material, the tilt angle reaches 12° as maximum and decreases with increasing temperature (Dardas 2016). Figure 1 represents the temperature dependence of the helical pitch as p−2(T) and p−1(T) for Ce3 and Ce8 compounds, respectively. This reveals a different behavior and non-linear nature of helicoid in the Ce8 compound compare with that in the Ce3 compound included in the measurement results presented later in this work.

The electro-optical method fulfills the conditions of small deformation and laminar flow (see Fig. 2 and also ref. Sackmann and Demus 1966). It will be demonstrated that comparing obtained results can give an insight into restructuring processes, which occurs in the studied chiral smectic FLC materials. This study is a continuation and extension of the previous work (Dardas 2016) in which the method has been described for the first time and the elasticity coefficients for the materials were determined. This work is focused on the rotational viscosity. The advantage presented in this work approach is the ability to determine the viscoelastic properties of the material using the linear electro-optic coefficient. An additional advantage is the measurement performed exactly in the same cell geometry as the electro-optical panel used in liquid crystal displays. The linear optical tests can be applied as one of the complementary methods for determining the mechanical properties of liquid crystals (Kuczyński et al. 2012).

Schematic cartoon representing the behavior of the ferroelectric smectic phase under applied electric field of different strengths. Molecules arranged in the smectic layers are schematically represented by blue/white ovals, and the direction of the applied electric field is shown by long black arrows

Theoretical background

The rheological properties of liquid crystals are similar to highly viscose liquids. Measurements of liquid crystals are usually performed on ordered cells which are limited by surfaces. Specifically, for thick samples (few hundred micrometers), an average bulk viscosity can characterize the rheological behavior of the mesophase. However, if the confinement dimensions are progressively reduced, the surface-induced ordering increasingly contributes to the equilibrium director field. In general, effects of a distortion of the equilibrium state by flow depend on the flow direction and the director field (Gurovich et al. 1991; Sengupta et al. 2013). Hence, there is a set of viscosity coefficients which depend upon the mutual orientation of the flow and director fields, which was experimentally demonstrated first time by Mięsowicz (1946). The experiments of Gähwiller (1973) dealt with five independent coefficients, which appear in the dissipative part of the stress tensor, as it is formulated by Ericksen (1960), Leslie (1966), and Parodi (1970). Those five coefficients have the dimension of viscosity and are known as the Leslie coefficients. Moreover, one can define an effective coefficient of viscosity when the molecules undergo a rotational motion, γ (Larson 1999; Stewart 2004). The linear combinations of the Leslie coefficients defining three Mięsowicz viscosities, i.e., η1, η2, and η3, and the rotational viscosity γ are schematically presented in Fig. 3.

Viscosities in nematodynamics: n parallel to the flow direction, η1; n parallel to the gradient of flow, η2; n perpendicular to the flow direction and to the gradient of flow, η3; and γ, rotational viscosity (Stewart 2004)

Unlike isotropic fluids, perturbation of liquid crystals alters the director alignment, and conversely, the director reorientation induces liquid crystal flow (Leslie et al. 1991; Leslie et al. 1992; Sengupta 2013). Affected by external electric, magnetic, optical, or flow fields, the out-of-equilibrium states are ubiquitous in the realm of liquid crystal research and applications. A detailed description of the continuum and flow behavior of chiral smectic liquid crystals can be found in the book by Jakli and Saupe (2006). The effect of the electric field on the liquid crystal material depends on the mesophase. In general, to determine the coefficient of viscosity (η1, η2, η3, or γ), it is necessary to induce a properly controlled flow or deformation using an external force. In ferroelectric liquid crystals, an applied electric field can be used as an external factor. Due to its conjugation with spontaneous polarization, the induction of flow or deformation can be easily realized. When the electric field E is applied parallel to the smectic layers (electric field vector is in the x), then, a moment of force acts on the unit of the C* smectic volume, P0 × E, where P0 is a spontaneous polarization of a single smectic layer and φ is the angle between the electric field vector E and the physical director c (i.e., the unit vector in the direction of the projection of the medium position of the long axis molecules on the plane of the smectic layer). Deformation of the molecular distribution causes a change in the macroscopic properties of the sample. In a non-disturbed chiral smectic C*, the position of c-director in the successive smectic layers is described by \( \varphi =\frac{2\pi \bullet z}{p} \); z is the coordinate in the direction normal to the smectic layers, whereas p is the pitch of the helix. The constitutive equations, used to determine the effect of deformations on the electric field, originate from Orsay LC Group and also were described by Pierański et al. (1977) and by Kuczyński (2003). The moment of force from a small external disturbance is balanced by the elastic and viscous torques that can be expressed with the equation of motion for the azimuthal angle (Panarin et al. 1998),

where K is the elasticity constant (for cone movement) and γ stands for the above-mentioned rotational viscosity (some more details on the origin of the specified equations are given in Appendix).

In the case of the chiral ferroelectric smectic C* phase, the condition of small deformations means that the change in the angle between c-directors in the neighboring smectic layers must be small in comparison to the equilibrium value of this angle (Wojciechowski et al. 2013). Moreover, the systems are assumed to possess helical superstructures with helix axes oriented along the z-axis, perpendicular to smectic planes. The linear electro-optic coefficient a (Dardas et al. 2006) describing the change of optic axis orientation under a weak electric field E which does not destroy the helicoidal structure can be expressed as:

where \( q=\frac{2\pi }{p} \), p is helix pitch, the tilt angle θ of the molecules in a smectic layer (in the ferroelectric smectic C* phase, chiral molecules are spontaneously tilted at a tilt angle with respect to the layer normal), and τG denotes the relaxation time of the Goldstone mode:

From the weak distortion solution of Eq. (1), the relation in Eq. (2), and the condition ωτG<<1, one obtains (see Appendix) the expression for the interlayer elasticity coefficient K (Dardas 2016):

The last relation (Eq. (4)) enables to calculate the coefficient K, as soon as parameters a (the linear electro-optic coefficient), P0 (the local spontaneous polarization), p (the helical pitch of structure), and θ (the tilt angle) are known. Additionally, from Eqs. (3) and (4), the rotational viscosity can be obtained if τG is known,

where \( {\tau}_{\mathrm{G}}=\frac{1}{2\pi {f}_{\mathrm{G}}} \) is the relaxation frequency of Goldstone mode, i.e., a relaxation mode related to the fluctuations of the long molecular axis in azimuthal direction with respect to the smectic layer normal. The formulae in Eqs. (4) and (5) are the basis for determination of the viscoelasticity of ferroelectric liquid crystals with helicoidal structure in the small deformation and the laminar flow limit.

Experimental

Two commercially available materials 4-(n-hexyloxy phenyl)-1-(2-fuethyl butyl) biphenyl-4-carboxylate (denoted Ce3) and 4-(2-methylbutyl) phenyl-4-n-octylbiphenyl-4-carboxylate (denoted as Ce8) and resulting binary mixture (denoted here as Ce3/8) composed from those materials in 50:50 weight ratio have been used for the investigations. All three FLC materials exhibit ferroelectric properties within a relatively broad temperature range. The mesomorphic properties of pure FLC materials and of the binary mixture were determined by complementary methods: differential scanning calorimetry, electro-optics, and dielectric spectroscopy. The characteristic textures and their changes were observed using polarized optical microscope (POM) equipped by the temperature chamber with temperature controller. The synthetic details and the mesomorphic behavior of those materials were presented earlier (Bone et al. 1984). Ferroelectric liquid crystal, denoted as Ce3, possesses the cholesteric (N*) and the tilted ferroelectric smectic C* (SmC*) phases with phase transition temperatures as follows: Cr 65.0 °C SmC* 77.5 °C N* 162.0 °C Iso. Absence of the orthogonal smectic A* phase for this material caused definite difficulties while obtaining a homogeneous alignment. The second material studied was also ferroelectric liquid crystal, denoted as Ce8; it possesses a very rich polymorphism between the isotropic and crystal phases: Cr 39.6 °C SmG 56.0 °C SmJ 65.0 °C SmF 67.0 °C SmC* 86.0 °C SmA* 124.0 °C N* 145.5 °C BP 147.0 °C Iso. The resulting binary mixture possesses the following sequence of mesophases: Cr 39.6 °C SmG 56.0 °C SmJ 65.0 °C SmF 67.0 °C SmC* 85.8 °C SmA* 123.2 °C N* 148.7 °C BP 150.0 °C Iso.

For the measurements, the materials under the study were introduced by means of capillarity action in standard planar cells produced by Linkam Co. (UK) of 5 μm thick with ITO electrodes coated with a planar alignment polymer layers. The cells were placed in a modified Mettler hot stage. Their temperature was stabilized using Digi-Sense TC-9500 temperature controller with the accuracy of about 0.1 K.

The measurement of optic axis deviation a in a weak electric field is essential for determination of the elastic constant K when the electro-optic method is used. This quantity was measured by detection of electro-optical response with a photodiode connected to a lock-in amplifier SR850 (Stanford Research) followed by the calibration procedure as described by Dardas et al. 2011. This calibration procedure allows expressing the experimental results as angular quantities independent on experimental conditions. The remaining quantities can be found using further methods and techniques presented in more details by Diamant et al. (1957), Dąbrowski et al. (1992), Kuczyński et al. (2002), Dardas and Kuczyński (2004), Jeżewski et al. (2008) Kuczyński (2010), Kuczyński et al. (2010) and Kuczyński et al. (2012). The relaxation time was determined from the measurement of electro-optic response versus frequency in order to determine the rotational viscosity of the system.

Results and discussion

The experimental results obtained recently (Dardas 2016) were used to calculate the twist elastic coefficient K using Eq. (4) in the weak external field limit, from the static properties of the light modulation depth. After that, in order to determine the rotational viscosity coefficient γ using Eq. (5), the frequency of Goldstone mode relaxation by the electro-optic method was measured. The frequency dependence of the real (corresponds to a dielectric dispersion) and imaginary part of the optical response (corresponds to a dielectric absorption curve) for Ce3 and Ce8 is presented in Fig. 4.

If the frequency dispersion and absorption of the electro-optical response are already known, relaxation times can be determined, followed by the rotational viscosity index. For Ce3 compound, the relaxation time decreases with temperature, whereas the relaxation time is not sensitive to temperature change in case of Ce8 compound. On the basis of the obtained results, the coefficients of rotational viscosity of the tested materials were derived. The temperature dependence of the rotational viscosity, γ, for Ce3 and Ce8 pure compounds and for the resulting Ce3/8 binary mixture are presented in Fig. 5. The rotational viscosity coefficient γ vanishes at the phase transition from the SmC* phase to the paraelectric phase without helically structure (SmA*) or, in our case, with a different kind of helix (N*). This can be expected because the rotational viscosity γ parameter describes the properties of the c-director, which vanish at this transition. It is important to mention that from the application point of view, as predicted, the coefficient of rotational viscosity of the binary mixture runs practically between the curves obtained for pure materials. The value of the viscosity coefficient in the ferroelectric SmC* phase of the tested materials at 72 °C was 22 mPa s for the Ce3 material, 38 mPa s for Ce8, and 29 mPa s for Ce3/8 binary mixture, respectively. The viscosity coefficient is the smallest for material lacking the smectic A* phase. In the binary mixture, the smectic A* phase was induced and shows the viscous consequence. The highest viscosity has been detected for Ce8 compound. For all three studied materials, the viscosity coefficients considerably decreasing with temperature increase.

The Arrhenius law was used to evaluate the rotational viscosity activation energy. Plot of lnγ versus inverse temperature is presented in Fig. 6 and shows a linear behavior in a wide temperature range far from the transition to the paraelectric phase. The obtained activation energy for the material Ce8 is equal to 0.67 eV within the ferroelectric SmC* phase and is comparable with the results obtained for other similar materials (see for example refs. Wojciechowski et al. 2013). The activation energy values obtained for Ce3/8 binary mixture increase to about 1.6 eV. In case of Ce3 compound with uncommon, direct transition from the twisted ferroelectric phase to the cholesteric phase, the activation energy is significantly increased. In this case, the increase in activation energy is probably caused by the slowing down of the reaction time and frustration of the helix.

The Arrhenius plot of the rotational viscosity, lnγ, versus reduced temperature for Ce3 (red diamonds) and Ce8 (green circle) pure compounds and for the resulting Ce3/8 (yellow stars) binary mixture. Symbols, experimental data; line, linear fit demonstrating temperature range where the Arrhenius law is obeyed

Conclusion

The main objective of this work was to check the viscoelastic behavior of a binary ferroelectric mixture and to compare the values with those obtained on the pure FLC materials—the original components of the mixture. In the specific system studied here, the experimental results reveal that if we know the viscoelastic properties, specifically the viscosity, of the pure components, it is possible to predict it for the resulting binary mixture, e.g., the data presented in this work clearly show that the viscoelastic properties of new binary Ce3/8 mixture can be pre-determined by well-known viscoelastic properties of Ce3 and Ce8 materials. Very promising, from the potentials application point of view in information visualization devices is the fact, that knowing the coefficients of pure liquid crystal material with the ferroelectric properties, we could to anticipate the viscoelastic properties in newly designed liquid crystalline mixtures. In case of ferroelectric liquid crystalline Ce3/8 binary mixture, the estimated coefficients of elasticity (Dardas 2016) and, in this work, the viscosity are practically between the elasticity and viscosity coefficients of the original Ce3 and Ce8 pure materials. Having available a database of viscoelastic properties of FLC materials, it will be quite possible to produce a binary or a multicomponent mixture with the desired viscoelastic behavior. In the future, it would be worthwhile to verify this hypothesis on different subsequent FLC materials and to expend the area of ferroelectric materials/mixtures to other polar mesophases, like antiferroelectric and ferrielectric smectic mesophases. An essential difference in the evolution of the rotational viscosity seems to have now its grounds on helicoidal features and the nature of the neighboring liquid crystalline phases.

References

Bone MF, Coates D, Davey AB (1984) Spontaneous polarization measurements on Ce3 and Ce8, two commercially available ferroelectric liquid crystals. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst 102:331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/01406568408070548

Bubnov A, Kašpar M, Novotná V, Hamplová V, Glogarová M, Kapernaum N, Giesselmann F (2008a) Effect of lateral methoxy substitution on mesomorphic and structural properties of ferroelectric liquid crystals. Liq Cryst 35(11):1329–1337. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678290802585525

Bubnov A, Novotná V, Hamplová V, Kašpar M, Glogarová M (2008b) Effect of multilactate chiral part of liquid crystalline molecule on mesomorphic behaviour. J Mol Struct 892:151–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2008.05.016

Bubnov A, Podoliak N, Hamplová V, Tomášková P, Havlíček J, Kašpar M (2016a) Eutectic behaviour of binary mixtures composed of two isomeric lactic acid derivatives. Ferroelectrics 495:105–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/00150193.2016.1136776

Bubnov A, Tykarska M, Hamplová V, Kurp K (2016b) Tuning the phase diagrams: the miscibility studies of multilactate liquid crystalline compounds. Phase Transit 89(9):885–893. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411594.2015.1087523

Clark NA and Lagerwall ST (1980) Submicrosecond bistable electro-optic switching in liquid crystals, Appl Phys Lett 36, 899/19. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.91359

Dąbrowski R, Szulc J, Sosnowska B (1992) The stability of the smectic C phase in mixtures: an influence of a dopant on the phase sequence and the tilt angle. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst 215:13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10587259208038508

Dardas D (2016) Electro-optic and viscoelastic properties of a ferroelectric liquid crystalline binary mixture. Phase Transit 89(4):368–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411594.2016.1149179

Dardas D, Kuczyński W (2004) Non−linear electrooptical effects in chiral liquid crystals. Opto-Electron Rev 12(3):277–280

Dardas D, Kuczynski W, Hoffmann J (2006) Measurements of absolute values of electrooptic coefficients in a ferroelectric liquid crystal. Phase Transit 79(3):213–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411590500448957

Dardas D, Kuczyński W, Nowicka K (2009) Determination of the bulk rotational viscosity coefficient in a chiral smectic C* liquid crystal. Phase Transit 82(6):444–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411590902972869

Dardas D, Kuczyński W, Hoffmann J, Jeżewski W (2011) Determination of twist elastic constant in antiferroelectric liquid crystals. Meas Sci Technol 22:085707. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-0233/22/8/085707

De Gennes PG (1974) Physics of liquid crystals, Pergamon, Oxford,

Diamant H, Drenck K, Pepinsky R (1957) Bridge for accurate measurement of ferroelectric hysteresis. Rev Sci Instrum 22:3033. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1715701

Dłubacz A, Marzec M, Dardas D, Żurowska M (2016) New antiferroelectric liquid crystal for use in LCD. Phase Transit 89(4):349–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411594.2015.1116531

Emelyanenko AV (2016) Induction of new ferrielectric smectic phases in the electric field. Ferroelectrics 495:129–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/00150193.2016.1136862

Emelyanenko AV, Ishikawa K (2013) Smooth transitions between biaxial intermediate smectic phases. Soft Matter 9:3497. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3SM27724K

Emelyanenko AV, Fukuda A, Vij JK (2006) Theory of the intermediate tilted smectic phases and their helical rotation. Phys Rev E 74:011705. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.74.011705

Ericksen JL (1960) Anisotropic fluids. Arch Ration Mech Anal 4:231–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00281389

Fitas J, Marzec M, Kurp K, Żurowska M, Tykarska M, Bubnov A (2017) Electro-optic and dielectric properties of new binary ferroelectric and antiferroelectric liquid crystalline mixtures. Liq Cryst 44(9):1468–1476. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678292.2017.1285059

Gähwiller C (1973) Direct determination of the five independent viscosity coefficients of nematic liquid crystals. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst 20:301–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/15421407308083050

Gurovich EV, Kats EI and Lebedev VV (1991) Orientational phase transitions in liquid crystals. Critical dynamics

Isozaki T, Fujikawa T, Takezoe H, Fukuda A, Hagiwara T, Suzuki Y, Kawamura I (1992) Competition between ferroelectric and antiferroelectric interactions stabilizing varieties of phases in binary mixtures of smectic liquid crystals. Jpn J Appl Phys 31(2):L1435–L1438. https://doi.org/10.1143/JJAP.31.L1435

Isozaki T, Fujikawa T, Takezoe H, Fukuda A, Hagiwara T, Suzuki Y, Kawamura I (1993) Devil's staircase formed by competing interactions stabilizing the ferroelectric smectic-C* phase and the antiferroelectric smectic-CA* phase in liquid crystalline binary mixtures. Phys Rev B 48:13439–13450. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.48.13439

Jakli A, Saupe A (2006) One- and two dimensional fluids, Properties of Smectic, Lamellar and Columnar Liquid Crystals, Taylor&Francis

Jeżewski W, Kuczyński W, Hoffmann J et al (2008) Comparison of dielectric and optical response of chevron ferroelectric liquid crystals. Opto−Electron Rev 16:281–286. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11772-008-0021-4

Jeżewski W, Kuczyński W, Dardas D, Nowicka K, Hoffmann J (2010) Field-induced dynamics of ferroelectric liquid crystals with elastic interfacial confinement. Soft Matter 6(12):2786–2792. https://doi.org/10.1039/b926122b

Kuczyński W (2003) Electro-optical studies of relaxation processes in chiral smectic liquid crystals. In: Haase W, Wróbel S (eds) Relaxation phenomena. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, p 422444

Kuczyński W (2010) Behavior of the helix in some chiral smectic-C* liquid crystals. Phys Rev E 81:021708. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.81.021708

Kuczyński W, Dardas D, Goc F et al (2000) Linear and quadratic electrooptic effects in antiferroelectric liquid crystals. Ferroelectrics 274:191–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/00150190008228430

Kuczyński W, Goc F, Dardas D, Dąbrowski R, Hoffmann J, Stryła B, Małecki J (2002) Phase transitions in a liquid crystal with long-range dipole order. Ferroelectrics 274:83–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/713716405

Kuczyński W, Dardas D, Nowicka K (2009) Determination of the bulk rotational viscosity coefficient in a chiral smectic C* liquid crystal. Phase Transit 80(6):444–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411590902972869

Kuczyński W, Nowicka K, Dardas D, Jeżewski W, Hoffmann J (2010) Determination of bulk values of twist elasticity coefficient in a chiral smectic C* liquid crystal. Opto-Electron Rev 18(2):176–180. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11772-010-0006-y

Kuczyński W, Dardas D, Hoffmann J, Nowicka K, Jeżewski W (2012) Comparison of methods for determination of viscoelastic properties in chiral smectics C*. Phase Transit 85:358–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411594.2011.646273

Kurp K, Czerwiński M, Tykarska M, Bubnov A (2017) Design of advanced multicomponent ferroelectric liquid crystalline mixtures with sub-micrometer helical pitch. Liq Cryst 44(4):748–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678292.2016.1239774

Lagerwall ST (1999) Ferroelectric and antiferroelectric liquid crystals. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim

Lagerwall JPF, Giesselmann F (2006) Current topics in smectic liquid crystal research. Chem Phys Chem 7:20–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.200500472

Lagerwall JPF, Scalia G (2012) A new era for liquid crystal research: applications of liquid crystals in soft matter nano-, bio- and microtechnology. Curr Appl Phys 12:1387–1412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cap.2012.03.019

Larson RG (1999) The structure and rheology of complex fluids. Oxford University Press, New York

Leslie FM (1966) Some constitutive equations for anisotropic fluids. Q J Mech Appl Math 19:357–370. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmam/19.3.357

Leslie FM, Stewart IW, Nakagawa M (1991) A continuum theory for smectic C liquid crystals. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst 198:443–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/00268949108033420

Leslie FM, Laverty JS, Carlsson T (1992) Continuum theory for biaxial nematic liquid crystals. Q Jl Mech Appl Math 45:595–606

Malik P, Raina KK, Bubnov A, Chaudhary A, Singh R (2010) Electro-optic switching and dielectric spectroscopy studies of ferroelectric liquid crystals with low and high spontaneous polarization. Thin Solid Films 519(3):1052–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2010.08.042

Marzec M, Fryń P, Tykarska M (2014) New antiferroelectric compound studied by complementary methods. Phase Transit 87(10–11):1011–1017. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411594.2014.953513

Mięsowicz M (1946) The three coefficients of viscosity of anisotropic liquids. Nature 158:27

Modlińska A, Dardas D, Jadżyn J, Bauman D (2011) Characterization of some fluorinated mesogens for application in liquid crystal displays. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst 542(1):28/[550]–36/[558]. https://doi.org/10.1080/15421406.2011.569515

Novotná V, Hamplová V, Kašpar M et al (2004) Phase diagrams of binary mixtures of antiferroelectric and ferroelectric compounds with lactate units in the mesogenic core. Ferroelectrics 309:103–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00150190490509980

Panarin YP, Kalinovskaya O, Vij JK (1998) The investigation of the relaxation processes in antiferroelectric liquid crystals by broad band dielectric and electro-optic spectroscopy. Liq Cryst 25:241–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/026782998206399

Parodi O (1970) Stress tensor for a nematic liquid crystal. J Phys 31:581–584. https://doi.org/10.1051/jphys:01970003107058100

Piecek W, Bubnov A, Perkowski P, Morawiak P, Ogrodnik K, Rejmer W, Żurowska M, Hamplová V, Kašpar M (2010) An effect of structurally non-compatible additive on the properties of a long-pitch orthoconic antiferroelectric mixture. Phase Transit 83:551–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411594.2010.499496

Pierański P, Guyon E, Keller P, Liébert L, Kuczyński W, Pierański P (1977) Optical study of a chiral smectic C under shear. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst 38:275–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/15421407708084393

Rosenblatt C, Pindak R, Clark NA, Meyer RB (1979) Freely suspended ferroelectric liquid-crystal films: absolute measurements of polarization, elastic constants, and viscosities. Phys Rev Lett 42:1220–1223. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.42.1220

Sackmann H, Demus D (1966) The polymorphism of liquid crystals. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst 2:81–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/15421406608083062

Sengupta A (2013) Topological microfluidics nematic liquid crystals and nematic colloids in microfluidic environment, Springer Theses, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00858-5_2,)

Stamatoiu O, Mirzaei J, Feng X, et al (2011) Nanoparticles in liquid crystals and liquid crystalline nanoparticles Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Liquid Crystals pp 331–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/128_2011_233

Stewart IW (2004) The static and dynamic continuum theory of liquid crystals, Taylor&Francis

Takezoe H, Kondo K, Miyasato K, Abe S, Tsuchiya T, Fukuda A, Kuze E (1984) On the methods of determining material constants in ferroelectric smectic C* liquid crystals. Ferroelectrics 58:55–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00150198408237858

Wojciechowski M, Tykarska M, Bąk GW (2013) Dielectric properties of ferrielectric subphase of liquid crystal MHPOPB. Scient Bull Phys, Technical University of Łódź 34:57–64

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Centre (NCN) Poland under Grant 2017/25/B/ST3/00564.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

In this appendix, the main steps to determine viscoelastic coefficients by the electro-optic method with weak electric fields are given.

We deal with the conditions in which the distortion of the helix in the approximation of small perturbation is realized. The distortion can be induced by the shear or by the electric field, and we assume that it does not change the tilted angle, θ. With this simplification, the director (or the c-director) has only one degree of freedom, i.e., the rotation around the z-axis or φ-angle and z is the coordinate along the direction normal to the smectic layers. Thus, the equation of motion for the c-director involves only the z component of the acting torques and has the form (Pierański et al. 1977; Stewart 2004),

The first term represents the elastic torque with the K elastic constant for the movement on the θ-preserving cone, which opposes the deformation from the unperturbed configuration φu = qz (\( q=\frac{2\pi }{p} \)).

The second term accounts for the rotational viscosity, and γ stands for the rotational viscosity coefficient. The right hand side represents the perturbation which is the torque M acting on a volume unit of liquid crystal. The helix deformation can be caused by the shear flow (e.g., Pierański et al. 1977) or any other periodic excitation which can induce a perturbation. If the external torque is caused by an electric field E, then, \( M=\left|\overrightarrow{P_0}\times \overrightarrow{E}\right| \), where P0 denotes the spontaneous polarization of the smectic layer and the electric field is applied across the boundary plates in the direction of z. With regard to the signs, as φ is the angle between the tilt plane (or c-director) and x, and together also between P and E. Consequently, the torque \( \overrightarrow{P_0}\times \overrightarrow{E}=-{P}_0E\sin \varphi \) is in the negative z direction for φ > 0. When the alternating field is applied, E = E0 cos(ωt), the resulting basic dynamics of SmC* (when the effects of flow and the dielectric effects ~E2 are negligible) is described by the frequently exploited in the literature equation of motion (Stewart 2004):

In the case of small deformations, which we deal in this work with, the solution to the above equation is assumed in the following form (Pierański et al. 1977; Kuczyński 2003),

The first term represents unperturbed configuration and the second the distortion of the same period as the applied field. Inserting the solution in the equation of motion in Eq. (6), the expression for the amplitude of distortion is obtained,

where τG is the relaxation time of the Goldstone mode:

The change in the optic axis orientation ∆α under weak electric field can be expressed in the limit ω → 0 as:

with the coefficient a independent on E0 (Dardas and Kuczyński 2004). On the other hand, the relation between Δα and the tilt angle θ of the molecules in a smectic layer with respect to the layer normal was given by Lagerwall (1999):

From Eqs. (10) and (11), one gets,

Taking into account Eqs. (8) and (12), the formula for the coefficient a is,

For small ωτG<<1, the above relation yields the expression for the interlayer elasticity coefficient:

The above relation (Eq. (4) in the main text) enables to calculate the elastic coefficient K with parameters a, P0, p, and θ which are from experiment. Also, knowing K and measuring the relaxation frequency of Goldstone mode fG = 1/2πτG, the rotational viscosity γ in Eq. (9) can be determined from the following relation (Eq. (5) in the main text),

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Dardas, D. Tuning the electro-optic and viscoelastic properties of ferroelectric liquid crystalline materials. Rheol Acta 58, 193–201 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00397-019-01129-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00397-019-01129-z