Abstract

Background

Age, multimorbidity, immunodeficiency and frailty of older people living in nursing homes make them vulnerable to COVID-19 and overall mortality.

Objective

To estimate overall and COVID-19 mortality parameters and analyse their predictive factors in older people living in nursing homes over a 2-year period.

Method

Design: A 2-year prospective longitudinal multicentre study was conducted between 2020 and 2022.

Setting: This study involved five nursing homes in Central Catalonia (Spain).

Participants: Residents aged 65 years or older who lived in the nursing homes on a permanent basis.

Measurements: Date and causes of deaths were recorded. In addition, sociodemographic and health data were collected. For the effect on mortality, survival curves were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and multivariate analysis using Cox regression.

Results

The total sample of 125 subjects had a mean age of 85.10 years (standard deviation = 7.3 years). There were 59 (47.2%) deaths at 24 months (95% confidence interval, CI, 38.6–55.9) and 25 (20.0%) were due to COVID-19, mostly in the first 3 months. In multivariate analysis, functional impairment (hazard ratio, HR 2.40; 95% CI 1.33–4.32) was a significant risk factor for mortality independent of age (HR 1.17; 95% CI 0.69–2.00) and risk of sarcopenia (HR 1.40; 95% CI 0.63–3.12).

Conclusion

Almost half of this sample of nursing home residents died in the 2‑year period, and one fifth were attributed to COVID-19. Functional impairment was a risk factor for overall mortality and COVID-19 mortality, independent of age and risk of sarcopenia.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Alter, Multimorbidität, Immunschwäche und Gebrechlichkeit älterer Menschen, die in Pflegeheimen leben, machen sie anfällig für COVID-19 und erhöhen die Gesamtmortalität.

Zielsetzung

Schätzung der Gesamt- und COVID-19-Mortalität und Analyse ihrer prädiktiven Faktoren bei älteren Menschen, die in Pflegeheimen leben, über einen Zeitraum von 2 Jahren.

Methode

Diese prospektive, multizentrische Längsschnittstudie wurde zwischen 2020 und 2022 in 5 Pflegeheimen in Zentral-Katalonien (Spanien) durchgeführt. Teilnehmer waren Bewohner im Alter von 65 Jahren oder älter, die dauerhaft in den Pflegeheimen lebten. Datum und Ursachen der Todesfälle wurden erfasst. Darüber hinaus wurden soziodemografische und gesundheitliche Daten erhoben. Für die Auswirkung der Sterblichkeit wurden Überlebenskurven nach der Kaplan-Meier-Methode und eine multivariate Analyse mittels Cox-Regression durchgeführt.

Ergebnisse

Die Gesamtstichprobe von 125 Personen hatte ein Durchschnittsalter von 85,10 Jahren (Standardabweichung = 7,3). Nach 24 Monaten traten 59 (47,2 %) Todesfälle auf (95 % Konfidenzintervall [KI] 38,6–55,9), von denen 25 (20,0 %) auf COVID-19 zurückzuführen waren, zumeist in den ersten 3 Monaten. In der multivariaten Analyse war die Funktionseinschränkung (Hazard-Ratio [HR]: 2,40; 95 % KI 1,33–4,32) ein signifikanter Risikofaktor für die Sterblichkeit, unabhängig vom Alter (HR: 1,17; 95 % KI 0,69–2,00) und dem Risiko der Sarkopenie (HR: 1,40; 95 % KI 0,63–3,12).

Schlussfolgerung

Fast die Hälfte dieser Stichprobe von Pflegeheimbewohnern starb innerhalb von 2 Jahren, ein Fünftel davon wurde auf COVID-19 zurückgeführt. Funktionseinschränkungen waren ein Risikofaktor für die Gesamt- und COVID-19-Mortalität, unabhängig von Alter und Sarkopenierisiko.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic began to have a major impact on society in 2019 [1] having unprecedented consequences on global health and economic systems.

In developed European countries with a very high older population the COVID-19 mortality was 83.7% for people > 70 years and 16.2% for people younger than 69 years in 2020 [2] with a higher prevalence of COVID-19 deaths in nursing homes (NH) [3]. Health problems and geriatric syndromes associated with ageing also determined the risk of mortality [4,5,6,7,8,9].

At the beginning of the pandemic Spain had a total of 326,613 people institutionalised in NHs [10] and a study conducted in Madrid reported a 14% mortality rate in older adults with COVID-19 in NHs [7]. The COVID-19 mortality has already been extensively studied in several countries, although most of these follow-ups have not exceeded 1 year [11]. Longer follow-ups would enable more accurate data and the identification of predictive factors that may be relevant to clinical practice.

The main aim of the study was to estimate overall and COVID-19 mortality parameters and analyse their predictive factors in older people living in NHs over a 2-year period.

Methodology

Study design and population

This is a 2-year multicentre observational cohort study. The study was conducted in five NH in Central Catalonia, Spain. It was designed following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) standards for cohort studies [12, 13]. Residents aged 65 years and older permanently living in NH were included. Those in a coma or palliative care (short-term prognosis), those who refused (or their legal guardian) to participate in the study and those who left the NH during the 2‑year cohort period were excluded.

Sample size

For the calculation of the sample, the article by Burgaña Agoües et al. (2021) was taken as a reference due to its methodological similarity to the present article: Burgaña studied pandemic mortality due to COVID-19 in Spain, in people over 65 years of age resident in NH. Considering the findings of Burgaña Agoües et al. (2021) [14], i.e. the difference in proportions between individuals with severe functional impairment (23.0%) and deceased (11.1%), and with a confidence interval (CI) of 95% and a power of 80%, a sample size of 122 participants was estimated.

Study procedures

The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and COVID-19 over the 2‑year follow-up period. The mortality registry included cause and date of death, deaths in total, deaths due to COVID-19 including confirmed cases, and deaths due to symptomatic suspicion of COVID-19 [15]. Additional COVID-19 data collected included the presence of the disease, whether they had symptoms [16], the performance of COVID-19 screening tests such as C‑reactive protein (CRP), serological tests, and/or rapid antigen tests for SARS-CoV‑2 (RAT) [17]. The information was collected through on-line interviews with NH professionals as due to COVID-19, they could not be accessed.

Sociodemographic and health information was obtained from health centre records and cross-checked with health professionals. All sociodemographic variables and those described in this article were collected at baseline (January 2020), just before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Falls (number) during the last year were obtained from NH registers. Nutritional status was assessed using the mini nutritional assessment (MNA) [18]. The SARC‑F [19] was used to identify individuals at risk of developing sarcopenia. Functional capacity was measured using the modified Barthel index and results were classified according to the degree of dependency as: independent, slightly dependent, moderately dependent, severely or totally dependent [20]. Continence status was reported using section H of the minimum data set (MDS) version 3.024 [21]. Cognitive status was assessed using the Pfeiffer scale [22] and frailty using the clinical frailty scale (CFS) [23]. Sedentary behaviour (SB) and waking-time movement behaviours (WTMB) were assessed using the ActivPAL 3TM activity monitor (PAL Technologies Ltd., Glasgow, UK) [24].

The study was conducted over a 2-year period and ended in March 2022.

Statistical analysis

The nominal and ordinal quantitative variables were expressed according to frequency in percentages and the quantitative variables with mean and standard deviation (SD). Survival curves were formed using the Kaplan-Meier method and multivariate analysis was performed by Cox regression, using the hazard ratio (HR) as the measure of effect. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the analysis.

Results

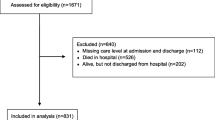

We recruited 125 people, 67.6% of the total number of NH residents in the main study. Finally, 7 (3.8%) participants who left NHs to reside elsewhere were excluded (Fig. 1).

The mean age of the participants was 85.1 years (SD = 7.3 years) and 104 (83.2%) were female. The mean number of months living in NH was 27.5 months (SD = 112.14 months). The analysis of health and sociodemographic variables is described in Table 1.

In the 2‑year period from baseline to the end of the study, 59 participants (47.2%) died, of whom 25 (20.0%) died from COVID-19 and 34 (27.2%) from other causes. All COVID-19 deaths occurred in the first year of the study: 44 (74.5%) of the 59 individuals had already died within the first 90 days (at the peak of COVID-19).

Survival and associated factors according to the variable mortality

In the bivariate analysis, mortality was associated with functional impairment, urinary incontinence (UI), faecal continence, risk of sarcopenia, % of waking time in SB and with a p-value of less than 0.05. All other health and sociodemographic variables were not significant (Table 2).

The variables were tested for collinearity and none of them showed collinearity with each other. A multivariate analysis was performed with the model with adjusted values including the variables age with severe functional impairment and risk of sarcopenia. The result showed that functional impairment predicted mortality independently of age (which was not statistically significant) and sarcopenia risk (Table 3).

Survival and associated factors according to the variable COVID-19 or other-cause mortality

In the univariate analysis, functional impairment, living in a private NH, being older than 86 years, malnutrition and being female were risk factors for COVID-19 mortality. Functional impairment was associated with mortality from other health causes with a p-value of less than 0.050 (Tables 4 and 5; Fig. 2).

We tested for collinearity between the variables and none of them were collinear with each other. The number of individuals in this variable is 59. Different combinations of significant variables, such as functionality, age and type of NH among others, were tested by multivariate analysis, but no significant results were found (Table 5).

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to examine the incidence of all-cause and COVID-19 mortality and to analyse the predictive factors in older NH residents over a 2-year period since the onset of the pandemic.

The results indicate that almost half of participants died with 20% being attributed to COVID-19. Most of the deaths (74.5%) were in the first 3 months of the study, coinciding with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. In the second year of the study, the survival curve became horizontal again, after the implementation of preventive measures. This study shows a higher incidence of mortality in the 1‑year period than other studies. Several articles on the pandemic phase report data on excess mortality [11]. A study in Barcelona reported a 3-month COVID-19 mortality rate of 11.1% in institutionalised older people [14]. For deaths from other causes, they reported excess mortality among institutionalised cases (34.8%) [14].

We also report the association of health, social and demographic variables with mortality: functional impairment, UI, sarcopenia risk and % of waking time in SB were found to be factors associated with mortality and functional impairment, type of NH and age were associated with COVID-19 mortality. The literature shows that UI and risk of sarcopenia are associated with mortality [25,26,27] and those who spent more time in SB had a higher risk of mortality [28].

Unlike other studies, our data show an increase of mortality in private NHs [29]. The NH type and size influenced mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in other studies [29]. Braun et al. (2020) attributed these results to the lack of organisation and shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) in private NHs [29].

This study has the limitation of the COVID-19 pandemic, which impeded access to NHs, increased deaths in older people and did not enable us to have a larger sample.

The strength of the study lies in the telematic data collection in NHs. This enabled us to extract real information on the health and social status of residents. The fact that we collected data prior to the start of the pandemic allowed us to make a comparison of the health and sociodemographic status of institutionalised older people. By having a cross-sectional analysis of the prepandemic sample, we provide data on the factors that predicted the risk of dying in a 2-year follow-up.

Conclusion

Almost half of this sample of NH residents died during the 2‑year observation period. One fifth of deaths were attributed to COVID-19 mostly in the first quarter, coinciding with the peak of the pandemic. Functional impairment was a risk factor for overall mortality and COVID-19 mortality, independent of age and risk of sarcopenia.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AHT:

-

Arterial hypertension

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CFS:

-

Clinical frailty scale

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease

- CVA:

-

Cerebral vascular accident

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ICC:

-

Interclass correlation coefficient

- MDS:

-

Minimum data set

- MNA:

-

Mini nutritional assessment

- NH:

-

Nursing homes

- PCR:

-

C‑reactive protein

- PPE:

-

Personal protective equipment

- RAT:

-

Rapid antigen tests

- SARC‑F:

-

Questionnaire assistance in walking, rising from chair, climbing stairs and falling

- SB:

-

Sedentary behaviour

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package Social Sciences

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- UI:

-

Urinary incontinence

- WTMB:

-

Waking-time movement behaviours

References

Licher S, Terzikhan N, Splinter MJ et al (2021) Design, implementation and initial findings of COVID-19 research in the Rotterdam Study: leveraging existing infrastructure for population-based investigations on an emerging disease. Eur J Epidemiol 36(6):649–654

Abbatecola AM, Antonelli-Incalzi R (2020) Editorial: Espiral de fragilidad COVID-19 en pacientes italianos mayores. Rev Nutr Salud Envejec 24(5):453–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1357-9

Levin AT, Owusu-Boaitey N, Pugh S et al (2022) Assessing the burden of COVID-19 in developing countries: systematic review, meta-analysis and public policy implications. BMJ Glob Health 7(5):e8477. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008477

Beard JR, Officer A, de Carvalho IA et al (2016) The World report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 387(10033):2145–2154. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00516-4

Damián J, Pastor-Barriuso R, García López FJ et al (2017) Urinary incontinence and mortality among older adults residing in care homes. J Adv Nurs 73(3):688–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13170

Escribà-Salvans A, Rierola-Fochs S, Farrés-Godayol P et al (2023) Risk factors for developing symptomatic COVID-19 in older residents of nursing homes: A hypothesis-generating observational study. JFSF 8(2):74–82. https://doi.org/10.22540/JFSF-08-074

Moreno-Torres V, de la Fuente S, Mills P, Muñoz A, Muñez E, Ramos A, Fernández-Cruz A, Arias A, Pintos I, Vargas JA, Cuervas-Mons V, de Mendoza C (2021) Major determinants of death in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 during the first epidemic wave in Madrid, Spain. Ann Univ Mariae Curie Sklodowska [Med] 100(16):E25634. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.000000000000025634

Regato-Pajares P, Villacañas-Novillo E, López-Higuera MJ et al (2023) Primary care and elderly people in nursing homes: proposals for improvement after the experience during the pandemic. Rev Clín Med Fam 16(1):24–32. https://doi.org/10.55783/rcmf.160105

Fallon A, Dukelow T, Kennelly SP, O’Neill D (2020) COVID-19 in nursing homes. QJM 113(6):391–392. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa136

Rodríguez Rodríguez P, Gonzalo Jiménez E (2022) COVID-19 in nursing homes: structural factors and experiences that support a change of model in Spain. Gaceta Sanit 36(3):270–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2021.09.005

Cases L, Vela E, Santaeugènia Gonzàlez SJ et al (2023) Excess mortality among older adults institutionalized in long-term care facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic: a populationbased analysis in Catalonia. Front Public Health 11:1208184. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1208184

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al (2008) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61(4):344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

Farrés-Godayol P, Jerez-Roig J, Minobes-Molina E et al (2021) Urinary incontinence and sedentary behaviour in nursing home residents in Osona, Catalonia: protocol for the OsoNaH project, a multicentre observational study. BMJ Open 11(4):e41152. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041152

Burgaña Agoües A, Serra Gallego M, Hernández Resa R et al (2021) Risk factors for COVID-19 morbidity and mortality in Institutionalised elderly people. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(19):10221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910221

Comas-Herrera A, Zalakain J Mortality associated with COVID-19 outbreaks in care homes: early international evidence. Resources to support community and institutional Long-Term Care responses to COVID-19. 2020;(April):1–6. https://ltccovid.org/2020/04/12/mortality-associated-with-covid-19-outbreaks-in-care-homes-early-international-evidence/

Dhama K, Patel SK, Natesan S et al (2020) COVID-19 in the elderly people and advances in vaccination approaches. Hum Vaccin Immunother 16(12):2938–2943. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1842683

López de la Iglesia J, Fernández-Villa T, Rivero A et al (2020) Predictive factors of COVID-19 in patients with negative RT-qPCR. Semergen 46(Suppl 1):6–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semerg.2020.06.010

Dewar AM, Thornhill WA, Read LA (1994) The effects of tefluthrin on beneficial insects in sugar beet. In: The mini nutritional assessment (MNA) and its use in grading the nutritional state of elderly patients, pp 987–992

Malmstrom TK, Miller DK, Simonsick EM et al (2016) SARC-F: a symptom score to predict persons with sarcopenia at risk for poor functional outcomes. J cachexia sarcopenia muscle 7(1):28–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12048

Cid-Ruzafa J, Damián-Moreno J (1997) Disability evaluation: Barthel’s index. Rev Esp Salud Publica 71(2):127–137 (Erratum in: Rev Esp Salud Publica 1997 Jul-Aug;71(4):411)

Klusch L (2012) SMD 3.0 and its impact on bladder and bowel care. Provider 38(6):33–37

Martínez de la Iglesia J, Dueñas Herrero R, Onís Vilches MC et al (2001) Spanish language adaptation and validation of the Pfeiffer’s questionnaire (SPMSQ) to detect cognitive deterioration in people over 65 years of age. Med Clin (Barc) 117(4):129–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0025-7753(01)72040-4

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C et al (2005) A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 173(5):489–495. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050051

Grant PM, Dall PM, Mitchell SL et al (2008) Activity-monitor accuracy in measuring step number and cadence in community-dwelling older adults. J Aging Phys Act 16(2):201–214. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.16.2.201

Huang P, Luo K, Wang C et al (2021) Urinary incontinence is associated with increased all-cause mortality in older nursing home residents: a meta-analysis. J Nurs Scholarsh 53(5):561–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12671

Yoshioka T, Kamitani T, Omae K et al (2021) Urgency urinary incontinence, loss of independence, and increased mortality in older adults: A cohort study. PLoS ONE 16:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245724

Yang M, Jiang J, Zeng Y et al (2019) Sarcopenia for predicting mortality among elderly nursing home residents. Medicine 98(7):e14546. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000014546

Ku PW, Steptoe A, Liao Y et al (2019) A threshold of objectively-assessed daily sedentary time for all-cause mortality in older adults: a meta-regression of prospective cohort studies. J Clin Med 8(4):564. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8040564

Braun RT, Yun H, Casalino LP et al (2020) Comparative performance of private equity-owned US nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 3(10):e2026702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.26702

Acknowledgements

We thank all the members of the study NH for their contribution to this work and the older adults who participated in the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hestia Chair from Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (grant number BI-CHAISS-2019/003) and the research grant from the Catalan Board of Physiotherapists Code R03/19.

Dyego Leandro Bezerra de Souza thank CNPq (Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) productivity grants 315962/2023-2.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anna Escriba-Salvans: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—reviewand editing. Eduard Minobes-Molina: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition. Pau Farrés-Godayol: formal analysis, writing—review and editing. Dyego Leandro Bezerra de Souza: writing—review and editing. Dawn A Skelton: supervision, writing—review and editing. Javier Jerez-Roig: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

A. Escribà-Salvans, J. Jerez-Roig, P. Farrés-Godayol, D.L. Bezerra de Souza, D.A. Skelton and E. Minobes-Molina declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of the University of Vic—Central University of Catalonia (registration number 92/2019 and 109/2020). Signed informed consent was obtained from the residents or the legal guardians. The project meets the criteria required in the Helsinki Declaration as well as the Organic Law 3/2018 (5 December) on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Scan QR code & read article online

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Escribà-Salvans, A., Jerez-Roig, J., Farrés-Godayol, P. et al. Health and sociodemographic determinants of excess mortality in Spanish nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a 2-year prospective longitudinal study. Z Gerontol Geriat (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-024-02294-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-024-02294-4