Abstract

Background

Delirium is a frequent psychopathological syndrome in geriatric patients. It is sometimes the only symptom of acute illness and bears a high risk for complications. Therefore, feasible assessments are needed for delirium detection.

Objective and methods

Rapid review of available delirium assessments based on a current Medline search and cross-reference check with a special focus on those implemented in acute care hospital settings.

Results

A total of 75 delirium detection tools were identified. Many focused on inattention as well as acute onset and/or fluctuating course of cognitive changes as key features for delirium. A range of assessments are based on the confusion assessment method (CAM) that has been adapted for various clinical settings. The need for a collateral history, time resources and staff training are major challenges in delirium assessment. Latest tests address these through a two-step approach, such as the ultrabrief (UB) CAM or by optional assessment of temporal aspects of cognitive changes (4 As test, 4AT). Most delirium screening assessments are validated for patient interviews, some are suitable for monitoring delirium symptoms over time or diagnosing delirium based on collateral history only.

Conclusion

Besides the CAM the 4AT has become well-established in acute care because of its good psychometric properties and practicability. There are several other instruments extending and improving the possibilities of delirium detection in different clinical settings.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Das Delir ist ein häufiges psychopathologisches Syndrom bei geriatrischen Patient:innen. Teilweise stellt es das einzige Symptom einer Akuterkrankung dar und geht mit einem hohen Komplikationsrisiko einher. Zur Erfassung sind daher praktikable Assessments wichtig.

Zielsetzung und Methodik

Rapid Review basierend auf einer aktuellen Medline-Suche und Querverweisanalyse zu verfügbaren Delir-Assessments mit Fokus auf den Einsatz im akutmedizinischen Bereich.

Ergebnisse

Insgesamt 75 Delir-Assessments wurden identifiziert. Viele detektierten als Schwerpunkt Aufmerksamkeitsstörungen sowie den für ein Delir charakteristischen akuten Beginn/fluktuierenden Verlauf. Eine Reihe von Assessments basieren auf der Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), die für verschiedene klinische Bereiche modifiziert wurde. Die Notwendigkeit zur Einholung einer Fremdanamnese, limitierte Zeitressourcen sowie die Schulung von Assessoren stellen bei vielen Assessments eine Herausforderung dar. Dieser wird u. a. dadurch begegnet, dass ein kurzes Screening einem ausführlicheren Assessment vorgeschaltet wird (z. B. ultra-brief CAM, UB-CAM). Alternativ muss bei manchen Assessments die Fremdanamnese nur fakultativ erhoben werden (z. B. 4 As Test, 4AT). Die meisten sind für das Screening von Patient:innen geeignet, es gibt aber auch Assessments, die eine Schweregradeinteilung oder ein Monitoring von Delir-Symptomen ermöglichen oder auch nur auf einer Fremdanamnese basieren.

Diskussion

Neben der CAM hat sich der 4AT in der Akutmedizin aufgrund der guten Praktikabilität und psychometrischen Charakteristika etabliert. Daneben existieren weitere geeignete Assessments, die einen zielgerichteten Einsatz in verschiedenen klinischen Bereichen erlauben und die Möglichkeiten des Delir-Assessments erweitern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Delirium is a frequent psychopathological and cognitive syndrome in geriatric patients and is associated with a high risk of acute care complications and negative outcomes [37]. It is the most important presenting phenotype of acute encephalopathy [61]. Therefore, delirium detection is an important part of evaluation of geriatric patients and feasible assessments are needed.

Background

Multiple risk factors contribute to the development of delirium and a multifactorial origin is common [28]. Various prevention and treatment options for delirium exist and range from optimizing risk factors (e.g. reducing anticholinergic medication) to the treatment of precipitating factors (e.g. pneumonia, electrolyte imbalances, pain) and the implementation of nonpharmacological multimodal care models [37]. For the adequate administration of preventive measures and treatment early identification of patients at high risk for and with delirium is essential; however, presentation of delirium can be heterogeneous and identification challenging.

Psychopathology and cognitive alterations in delirium

For a tailored use of delirium screening instruments, it is important to understand the different aspects of delirium as a psychopathological syndrome and its diagnostic criteria. In the International Classification of Diseases 10th edition (ICD-10) the syndrome of delirium is described as a rather variable combination of different psychopathological disturbances with a non-specific organic etiology (Table 1; [53]). Besides altered consciousness, an alteration of attention, perception, (logical) thinking, memory, psychomotor behavior, emotion or the sleep-wake schedule might be present.

Different subtypes of delirium exist: hyperactive delirium accounts for 20% of cases and is characterized by psychomotor agitation and restlessness [43]. It often includes pulling out tubes and is disrupting for hospital procedures, and is therefore an eye-catcher diagnosis for hospital professionals. In contrast hypoactive delirium, accounting for 30% of cases, presents with reduced psychomotor activity and patients are often misdiagnosed with depression or severe dementia. About 45% of delirious patients can show both hyperactive and hypoactive symptoms indicating a fluctuating course of disease.

Delirium can also be accompanied by psychotic symptoms. More than 40% of patients display predominantly optical hallucinations or delusions, such as being poisoned or persecuted [45].

The reference standard for delirium diagnosis has most commonly been the psychopathological examination through a skilled psychiatrist. The delirium rating scale in its original and revised version (DRS-R-98) sticks very closely to the various possibilities of psychopathological disturbances that can be found in delirium and tries to operationalize this psychopathological examination [58, 59]. Therefore, it is time-consuming and relatively complex to administer.

Development of the confusion assessment method (CAM)

In 1990 the first version of the confusion assessment method (CAM) was introduced, which is based on four core criteria [2, 29]. These criteria were derived from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised (DSM-III-R), a literature review as well as the discussion of an expert panel. Fig. 1 shows the CAM diagnostic algorithm in a schematic way.

Since its introduction CAM-based delirium diagnosis has become the gold standard of delirium detection. Many subsequently developed assessment tools focused on inattention and acute onset/fluctuating course as core diagnostic criteria, as defined in the DSM‑5 in 2013 [3]. Also, the upcoming ICD-11 shifts its focus towards these criteria for delirium definition [33]. The assessment of other cognitive disturbances, such as logical thinking was skipped as it was too complex and less valid. Table 1 compares core diagnostic criteria and involved psychopathological findings of delirium according to ICD-10 and ICD-11 (Table 1; [26, 27]). The comparison shows how the definition of delirium has developed from a heterogeneous psychopathological syndrome to a more specific diagnosis based primary on temporal onset, vigilance and attention, so that the needs of acute and emergency care physicians in daily routine can be better addressed.

This review, therefore, presents a summary of the available evidence on the broad variety of delirium assessments and provides suggestions on delirium detection tools that might be particularly useful in an acute care setting.

Methods

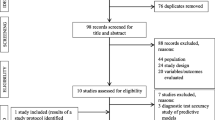

To identify the most relevant assessments, the Medline database was searched for reviews and validation articles of delirium screening instruments in older patients. Inclusion criteria were evaluation of assessment instruments in the context of delirium, English or German language and published between 2001 and 2021 (see supplementary material 1 for search string). These publications were screened for existing tests and the psychometric properties. In a second step, the cross-referenced literature of these reviews was examined in addition to the validation studies found to collect the primary literature of the respective assessments and extract further details. Thirdly, the Network for Investigation of Delirium: Unifying Scientists (NIDUS) website was used for an additional cross-reference search [41]. All instruments were investigated in detail by checking the full texts of the corresponding publications and extracting data on the number of study participants, investigators, scoring method, psychometric properties, time required for application and further aspects.

Fig. 2 illustrates the search, screening and selection process.

Results

The search of Medline, cross-references and NIDUS website revealed 118 full-text articles that were evaluated in detail. A total of 75 delirium assessments were identified of which a selection of 15 tools with high clinical practicability and satisfactory psychometric properties are presented (Table 2). All other tools can be found in a separate table (Table S1) in the supplementary material.

The CAM family

A total of 13 tools belonging to the CAM family were identified, all focusing on the 4 core symptoms: acute onset and/or fluctuating course, inattention, disorganized thinking and altered level of consciousness.

All CAM derivatives share the underlying diagnostic algorithm but differ in their structure and targeted group of persons. Most instruments are designed for patient interviews supplemented by collateral history from relatives, staff and medical records, e.g. CAM, CAM-severity scale (CAM-S), brief CAM (bCAM) and CAM for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) [11, 20, 30]. They often include an informal interview by which the presence of the core symptoms is evaluated. An example for a clearly structured variant is the 3‑minute diagnostic CAM (3D-CAM) with 10 questions to be answered by the patient, 10 questions to be answered by the interviewer and 2 optional questions requiring collateral history provided by relatives, friends and/or caregivers and medical records examination. Other CAM instruments are based on patient observation, e.g. nursing home CAM (NH-CAM) or caregiver interview, e.g. family CAM (FAM-CAM) [9, 51]. Furthermore, several variants address specific subgroups of patients, such as the CAM-ICU, which is also applicable to intubated patients, or the CAM for the emergency department (CAM-ED) [10, 18].

The CAM and its derivatives have many advantages but also some disadvantages. Advantages are the short examination duration, the structured evaluation algorithm and the convincing results of numerous validation studies with sensitivity and specificity values of 90–100% for delirium diagnosis compared to extensive and time-consuming clinical diagnostics; however, an important disadvantageous aspect is that for correct application of most CAM instruments intensive training is required to ensure valid and reliable test results. Some studies demonstrated poor sensitivity when the CAM was conducted by untrained or insufficiently trained raters [47, 48]. For example, the symptom disorganized thinking requires an experienced assessor for its detection. This issue has been addressed by deriving the 3D-CAM with more operationalized features [38]. In future this limitation might be overcome as the new definitions of delirium according to DSM‑5 and ICD-11 no longer include the symptom of impaired thinking.

Other delirium detection tools

For the emergency department and many other clinical settings there is a need for easy and quick screening tools. Examples for such assessments that could be integrated in daily clinical routine are the 4 As test (4AT) and the nursing delirium screening scale (Nu-DESC) [5, 15]. The 4AT has recently been evaluated against the CAM showing significant better sensitivity in a multicenter study [50].

As inattention is a characteristic delirium symptom many assessments that address this aspect have been evaluated in acute care and emergency settings [60]. The most popular of these is the months of the year backwards test (MOTYB) that provides a very quick option to screen for this feature. It is included in many assessments that combine testing for different aspects of delirium, such as the CAM. Several studies have evaluated its singular use in the context of delirium reporting high sensitivity and specificity [24]. Efforts have been made to further simplify the scoring method while maintaining good psychometric properties [23]. Another instrument, the bedside confusion scale (BCS), includes the MOTYB and adds one more question to assess a second delirium feature: psychomotor disturbance [52].

There are also easy to use tools focusing on the core feature acute onset. An example is the single question in delirium (SQID), which determines acute confusion by asking a relative or caregiver: “Do you feel that [patient’s name] has been more confused lately?” [48]. The SQiD can be used as a screening as well as a monitoring instrument for hospital staff.

An example for a quick tool examining the vigilance/level of consciousness of a patient, the change of which is another core feature of delirium, is the Richmond agitation sedation scale (RASS) [21]. It is widely used in intensive care units. The instrument assesses the vigilance on a scale from −5 (unarousable) to +4 (combative). There is a modified version, the mRASS, which has been optimized by adding the level of attention to each category [7].

There have been numerous attempts to use other tests originally designed for dementia diagnostics as delirium detection tools, for example the clock drawing test (CDT), but the studies revealed poor accuracy for this purpose, independent of the scoring method [1]. Other examples are the short portable mental status questionnaire (SPMSQ) or the abbreviated mental test (AMT), which are suitable to detect early dementia symptoms, but not to distinguish between dementia and delirium [8, 12].

While most of the identified tools serve solely as screening tools, some are also appropriate for monitoring the course of delirium. This group primarily comprises instruments including severity scoring and thus offering the possibility to observe change including the effect of measures taken. Examples are the CAM‑S, Nu-DESC or delirium observation screening scale (DOSS) [15, 30, 49].

Discussion

Over the last decades different assessments supportive for delirium diagnosis have been developed. These assessments differ in length and structure, psychometric performance, screening vs. monitoring abilities and whether the patient or an informant is assessed. The main goal of a delirium screening tool should be the differentiation of delirium as a cause of cognitive impairment in an emergency/acute care setting. In this setting major differential diagnoses of delirium are dementia and delirium superimposed on dementia (DSD).

Delirium vs. dementia vs. delirium superimposed on dementia

The focus on inattention most delirium assessments share seems feasible for different reasons: inattention is a typical feature of delirium but not dementia, and is easy and fast to evaluate in any acute care setting [14, 27]. In dementia inattention is typically not altered unless disease progresses to severe stages. Nevertheless, in non-Alzheimer’s dementias, such as Parkinson’s disease dementia, inattention might be a cognitive domain altered in earlier stages [6].

Acute change in cognitive function is another important feature to discriminate delirium from dementia. In contrast to delirium, dementia is characterized by a chronic progressive disease course. Therefore, a second focus of many delirium assessments is the documentation of acute onset and/or fluctuating course, a central feature of the CAM family; however, a main limitation is the necessity to obtain collateral history, particularly difficult in emergency situations.

Assessments like the UB-CAM or the delirium triage screen (DTS) address this limitation by combining a short screening with a focus on inattention, followed by a second assessment that includes collateral history [20, 40]. The 4AT, that enjoys growing popularity, contains the item acute onset/fluctuating course but its presence is not mandatory for positive delirium screening [50, 57].

In order to better discriminate delirium from DSD tools have been validated to address pre-existing cognitive decline by a structured collateral history. Good psychometric properties have been shown for the informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE) and the Alzheimer’s disease 8 (AD8) [14, 32].

Psychomotor disturbances, delusions and hallucinations

Psychomotor change has been added to the CAM algorithm to improve specificity in discriminating delirium and dementia [55]. In addition, the combination of a letter recognition attention test with the observational scale of level of arousal (OSLA) improved test performance compared to both individual tests [46].

Further frequent psychopathologic findings found in delirium are delusions and hallucinations. They are usually not integrated into commonly used assessments because they lack sensitivity and specificity for delirium diagnosis although they often have therapeutic consequences. Antipsychotic treatment should, however, only be used for very distressing delusions and hallucinations [31].

Additional diagnostics

Several other diagnostic techniques have been evaluated for delirium diagnostics. Electroencephalography (EEG) can visualize alterations in brain functioning that are common in delirium, and shows potential even in differentiating delirium from dementia [54]. Recently a study described a short 1‑min single-channel EEG with new automated power analysis as a potential delirium detection tool [42]. Besides this example most EEG studies need experienced staff to obtain valid results and are, therefore, currently not implemented on a large scale. Neuroimaging, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) that detects network disintegration, or fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) that shows focal hypometabolism in the posterior cingulate cortex, an important region for attention, can elucidate further pathophysiology but are also costly and complex to administer [19, 39]. Actimetry or other digitalized assessments are still in their infancy; however, 14 of 16 patients with CAM-positive delirium in the Canadian PredicT study were able to use a tablet-based “serious game” tapping on targets, showing digital assessments as a feasible approach [35]. A multicenter proof of assessing inattention is pursued by the DelApp. This smartphone app tests attention by presentation and recall of a sequence of symbols [56]. Other smartphone applications offer digital versions of common interview-based assessment tools facilitating documentation and practicability of the assessments [4].

Conclusion

Delirium is a common neuropsychiatric syndrome in geriatric patients especially in the context of emergency medicine and acute inpatient care. Its regular screening and monitoring should be mandatory. Many tailored delirium assessments with good psychometric properties for screening and monitoring have been adapted for emergency and acute care medicine needs.

Most of these assessments focus on inattention and acute onset/fluctuating course of disease in order to enable discrimination of delirium from dementia. The increasingly popular 4AT and several CAM-derived assessments include both items and can be used with confidence in different acute care settings. Imaging techniques and electronic assessments, such as mobile apps, are still not routinely available and feasible. Assessment selection should be driven by clinical setting as well as staff training, available time resources, feasibility and validity.

Change history

18 May 2022

An Erratum to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-022-02071-1

References

Adamis D, Morrison C, Treloar A et al (2005) The performance of the clock drawing test in elderly medical inpatients: does it have utility in the identification of delirium? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 18:129–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988705277535

American Psychiatric Association (1987) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd edn. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‑5, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C

Armstrong B, Habtemariam D, Husser E et al (2021) A mobile app for delirium screening. JAMIA Open. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/ooab027

Bellelli G, Morandi A, Davis DHJ et al (2014) Validation of the 4AT, a new instrument for rapid delirium screening: a study in 234 hospitalised older people. Age Ageing 43:496–502. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu021

Bronnick K, Emre M, Lane R et al (2007) Profile of cognitive impairment in dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease compared with Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78:1064–1068. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2006.108076

Chester JG, Harrington BM, Rudolph JL, VA Delirium Working Group (2012) Serial administration of a modified richmond agitation and sedation scale for delirium screening: modified RASS for identifying delirium. J Hosp Med 7:450–453. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1003

Chonchubhair NA, Valacio R, Kelly J, O’Keefe S (1995) Use of the abbreviated mental test to detect postoperative delirium in elderly people. Br J Anaesth 75:481–482. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/75.4.481

Dosa D, Intrator O, McNicoll L et al (2007) Preliminary derivation of a nursing home confusion assessment method based on data from the minimum data set: NURSING HOME CONFUSION ASSESSMENT MODEL. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:1099–1105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01239.x

Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR et al (2001) Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA 286:2703–2710. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.21.2703

Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J et al (2001) Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med 29:1370–1379. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-200107000-00012

Erkinjuntti T, Sulkava R, Wikström J, Autio L (1987) Short portable mental status questionnaire as a screening test for dementia and delirium among the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 35:412–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1987.tb04662.x

Fick DM, Inouye SK, Guess J et al (2015) Preliminary development of an ultrabrief two-item bedside test for delirium. J Hosp Med 10:645–650. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2418

Fong TG, Davis D, Growdon ME et al (2015) The interface between delirium and dementia in elderly adults. Lancet Neurol 14:823–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00101-5

Gaudreau J‑D, Gagnon P, Harel F et al (2005) Fast, systematic, and continuous delirium assessment in hospitalized patients: the nursing delirium screening scale. J Pain Symptom Manage 29:368–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.07.009

Gaudreau J‑D, Gagnon P, Harel F, Roy M‑A (2005) Impact on delirium detection of using a sensitive instrument integrated into clinical practice. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 27:194–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.01.002

van Gemert LA, Schuurmans MJ (2007) The Neecham confusion scale and the delirium observation screening scale: capacity to discriminate and ease of use in clinical practice. BMC Nurs 6:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-6-3

Grossmann FF, Hasemann W, Graber A et al (2014) Screening, detection and management of delirium in the emergency department—a pilot study on the feasibility of a new algorithm for use in older emergency department patients: the modified confusion assessment method for the emergency department (mCAM-ED). Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 22:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-7241-22-19

Haggstrom LR, Nelson JA, Wegner EA, Caplan GA (2017) 2‑18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in delirium. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 37:3556–3567. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271678X17701764

Han JH, Wilson A, Vasilevskis EE et al (2013) Diagnosing delirium in older emergency department patients: validity and reliability of the delirium triage screen and the brief confusion assessment method. Ann Emerg Med 62:457–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.05.003

Han JH, Vasilevskis EE, Schnelle JF et al (2015) The diagnostic performance of the richmond agitation sedation scale for detecting delirium in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 22:878–882. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12706

Hasemann W, Grossmann FF, Stadler R et al (2018) Screening and detection of delirium in older ED patients: performance of the modified confusion assessment method for the emergency department (mCAM-ED). A two-step tool. Intern Emerg Med 13:915–922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-017-1781-y

Hasemann W, Grossmann FF, Bingisser R et al (2019) Optimizing the month of the year backwards test for delirium screening of older patients in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 37:1754–1757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.06.035

Hasemann W, Duncan N, Clarke C et al (2021) Comparing performance on the months of the year backwards test in hospitalised patients with delirium, dementia, and no cognitive impairment: an exploratory study. Eur Geriatr Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-021-00521-4

Husser EK, Fick DM, Boltz M et al (2021) Implementing a rapid, two-step delirium screening protocol in acute care: barriers and facilitators. J Am Geriatr Soc 69:1349–1356. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17026

ICD (2019) ICD-10 version: 2019. https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en. Accessed 20 Aug 2021

ICD (2021) ICD-11 for mortality and morbidity statistics. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en. Accessed 19 Aug 2021

Inouye SH, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS (2014) Delirium in older people. Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1

Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA et al (1990) Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 113:941–948. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941

Inouye SK, Kosar CM, Tommet D et al (2014) The CAM-S: development and validation of a new scoring system for delirium severity in 2 cohorts. Ann Intern Med 160:526. https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-1927

Inouye SK, Marcantonio ER, Metzger ED (2014) Doing damage in delirium: the hazards of antipsychotic treatment in elderly persons. Lancet Psychiatry 1:312–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70263-9

Jackson TA, MacLullich AMJ, Gladman JRF et al (2016) Diagnostic test accuracy of informant-based tools to diagnose dementia in older hospital patients with delirium: a prospective cohort study. Age Ageing 45:505–511. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw065

Khoury B, Kogan C, Daouk S (2017) International classification of diseases, 11th edn., pp 1–6 (ICD-11)

Koster S, Hensens AG, Oosterveld FGJ et al (2009) The delirium observation screening scale recognizes delirium early after cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 8:309–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.02.006

Lee JS, Tong T, Tierney MC et al (2019) Predictive ability of a serious game to identify emergency patients with unrecognized delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc 67:2370–2375. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16095

Lin H‑S, Eeles E, Pandy S et al (2015) Screening in delirium: a pilot study of two screening tools, the simple query for easy evaluation of consciousness and simple question in delirium: a pilot study for screening delirium. Australas J Ageing 34:259–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12216

Marcantonio ER (2017) Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med 377:1456–1466. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1605501

Marcantonio ER, Ngo LH, O’Connor M et al (2014) 3D-CAM: derivation and validation of a 3-minute diagnostic interview for CAM-defined delirium: a cross-sectional diagnostic test study. Ann Intern Med 161:554. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-0865

van Montfort SJT, van Dellen E, van den Bosch AMR et al (2018) Resting-state fMRI reveals network disintegration during delirium. Neuroimage Clin 20:35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2018.06.024

Motyl CM, Ngo L, Zhou W et al (2020) Comparative accuracy and efficiency of four delirium screening protocols. J Am Geriatr Soc 68:2572–2578. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16711

Network for Investigation of Delirium—Unifying Scientists (NIDUS) (2021) Measurement and harmonization core

Numan T, van den Boogaard M, Kamper AM et al (2019) Delirium detection using relative delta power based on 1‑minute single-channel EEG: a multicentre study. Br J Anaesth 122:60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2018.08.021

O’Keeffe ST, Lavan JN (1999) Clinical significance of delirium subtypes in older people. Age Ageing 28:115–119. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/28.2.115

O’Regan NA, Ryan DJ, Boland E et al (2014) Attention! A good bedside test for delirium? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 85:1122–1131. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2013-307053

Paik S‑H, Ahn J‑S, Min S et al (2018) Impact of psychotic symptoms on clinical outcomes in delirium. PLoS ONE 13:e200538. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200538

Richardson SJ, Davis DHJ, Bellelli G et al (2017) Detecting delirium superimposed on dementia: diagnostic accuracy of a simple combined arousal and attention testing procedure. Int Psychogeriatr 29:1585–1593. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217000916

Ryan K, Leonard M, Guerin S et al (2009) Validation of the confusion assessment method in the palliative care setting. Palliat Med 23:40–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216308099210

Sands M, Dantoc B, Hartshorn A et al (2010) Single question in delirium (SQiD): testing its efficacy against psychiatrist interview, the confusion assessment method and the memorial delirium assessment scale. Palliat Med 24:561–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216310371556

Schuurmans MJ, Shortridge-Baggett LM, Duursma SA (2003) The delirium observation screening scale: a screening instrument for delirium. Res Theory Nurs Pract 17:31–50. https://doi.org/10.1891/rtnp.17.1.31.53169

Shenkin SD, Fox C, Godfrey M et al (2019) Delirium detection in older acute medical inpatients: a multicentre prospective comparative diagnostic test accuracy study of the 4AT and the confusion assessment method. BMC Med 17:138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1367-9

Steis MR, Evans L, Hirschman KB et al (2012) Screening for delirium using family caregivers: convergent validity of the family confusion assessment method and interviewer-rated confusion assessment method. J Am Geriatr Soc 60:2121–2126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04200.x

Stillman MJ, Rybicki LA (2000) The bedside confusion scale: development of a portable bedside test for confusion and its application to the palliative medicine population. J Palliat Med 3:449–456. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2000.3.4.449

Tassé MJ (2017) International classification of diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314281848_International_Classification_of_Diseases_10th_Edition_ICD-10. Accessed 22 Aug 2021

Thomas C, Hestermann U, Walther S et al (2008) Prolonged activation EEG differentiates dementia with and without delirium in frail elderly patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79:119–125. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2006.111732

Thomas C, Kreisel SH, Oster P et al (2012) Diagnosing delirium in older hospitalized adults with dementia: adapting the confusion assessment method to international classification of diseases, tenth revision, diagnostic criteria. J Am Geriatr Soc 60:1471–1477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04066.x

Tieges Z, Stíobhairt A, Scott K et al (2015) Development of a smartphone application for the objective detection of attentional deficits in delirium. Int Psychogeriatr 27:1251–1262. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610215000186

Tieges Z, Lowrey J, MacLullich AMJ (2021) What delirium detection tools are used in routine clinical practice in the United Kingdom? Survey results from 91 % of acute healthcare organisations. Eur Geriatr Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-021-00507-2

Trzepacz PT, Baker RW, Greenhouse J (1988) A symptom rating scale for delirium. Psychiatry Res 23:89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(88)90037-6

Trzepacz PT, Mittal D, Torres R et al (2001) Validation of the delirium rating scale-revised-98: comparison with the delirium rating scale and the cognitive test for delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 13:229–242. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.13.2.229

Voyer P, Champoux N, Desrosiers J et al (2016) Assessment of inattention in the context of delirium screening: one size does not fit all! Int Psychogeriatr 28:1293–1301. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216000533

Wilson JE, Mart MF, Cunningham C et al (2020) Delirium. Nat Rev Dis Primers 6:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-00223-4

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

S. Brefka, G. W. Eschweiler, D. Dallmeier, M. Denkinger and C. Leinert declare that they have no competing interests.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies performed were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

Additional information

Scan QR code & read article online

The original online version of this article was revised:

Page 109, Table 2, mCAM-ED

Column Screening vs. monitoring/Items:

2. If inattention present → MSQ for identifying cognitive impairment, Comprehension subtest of CTD for identifying disorganized thinking

Column Scoring:

Modified CAM algorithm: 1a (acute onset) AND 1b (fluctuating course) + 2 + (3 or 4) positive = diagnosed delirium

1a OR 1b + 2 + (3 or 4) positive = suspected delirium

Page 111, Legend table 2:

As a replacement for SPMSQ: MSQ mental status questionnaire

Supplementary Information

391_2021_2003_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary material 1: Search string in Medline (via PubMed) and Supplementary material 2: Table S1 with additional delirium detection tools

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brefka, S., Eschweiler, G.W., Dallmeier, D. et al. Comparison of delirium detection tools in acute care. Z Gerontol Geriat 55, 105–115 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-021-02003-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-021-02003-5