Abstract

Purpose

Intestinal anastomosis is a crucial step in most intestinal resections, as anastomotic leakage is often associated with severe consequences for affected patients. There are especially two different techniques for hand-sewn intestinal anastomosis: the interrupted suture technique (IST) and the continuous suture technique (CST). This study investigated whether one of these two suture techniques is associated with a lower rate of anastomotic leakage.

Methods

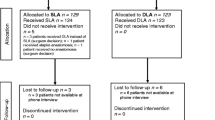

A retrospective review of 332 patients with Crohn’s disease who received at least one hand-sewn colonic anastomosis at our institution from 2010 to 2020 was performed. Using propensity score matching 183 patients with IST were compared to 96 patients with CST in regard to the impact of the anastomotic technique on patient outcomes.

Results

Overall anastomotic leakage rate was 5%. Leakage rate did not differ between the suture technique groups (IST: 6% vs. CST: 3%, p = 0.393). Multivariate analysis revealed the ASA score as only independent risk factor for anastomotic leakage (OR 5.3 (95% CI = 1.2–23.2), p = 0.026). Suture technique also showed no significant influence on morbidity and the re-surgery rate in multivariate analysis.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that the chosen suture technique (interrupted vs. continuous) has no influence on postoperative outcome, especially on anastomotic leakage rate. This finding should be confirmed by a randomized controlled trial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intestinal resections are one of the most common procedures in abdominal surgery. In the context of intestinal resections, intestinal anastomosis are of particular importance, as anastomotic leakage has far-reaching consequences for the affected patients including high re-surgery rates, higher risk of accompanying morbidities and longer hospital stays as well as impaired quality of life [1,2,3,4,5,6]. This aspect applies even more to patients with Crohn’s disease, as they have an increased risk of anastomotic leaks compared to patients without Crohn’s disease [7, 8].

There are different known risk factors associated with anastomotic leakage including aspects of surgical technique [7,8,9,10,11]. There are a number of technical variations for intestinal anastomosis regarding different aspects like kind of anatomical reconstruction (end-to-end vs. end-to-side vs. side-to-side), kind of suture techniques (stapled vs. hand-sewn, interrupted vs. continuous suture technique, single vs. double-layered technique) as well as the used suture material [12,13,14]. Therefore, the variability of the surgical technique for intestinal anastomosis may be one of the greatest among surgeons. And the “surgical school” may play a unique role for the surgical technique of the intestinal anastomosis.

In particular, there is a lack of sufficient evidence for the question of interrupted suture technique (IST) versus continuous suture technique (CST) [15]. Experimental investigations suggest that the interrupted suture technique might be associated with a better perfusion of anastomosis, whereas the continuous suture might offer a better sealing of the anastomosis [16]. Moreover, advocates of the continuous technique allege that the continuous suture may be able to save costs and operating time in comparison to the interrupted suture technique. However, until now there are only two retrospective studies that compared IST and CST with conflicting results. While a more recent study with 347 patients was able to show a significant difference between the suture techniques (IST: 16% vs. CST: 2.5%, p = 0,001), another investigation with only 53 patients showed no difference in the insufficiency rate (IST: 3.7% vs. CST: 3.8%) [10, 17].

Therefore, we focused on the influence of hand-sewn interrupted suture technique (IST) versus continuous suture technique (CST) on the postoperative outcome, especially on leakage rate and chose the high-risk population of patients with Crohn’s disease.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively analyzed 332 consecutive patients with Crohn’s disease who received an intestinal resection and anastomosis from 2010 to 2020 at the University Hospital Erlangen. Patients had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) age greater than or equal to 18 years; (2) histologically proven Crohn’s disease; (3) at least one colonic anastomosis; (4) intestinal anastomosis in hand-sewn technique. Anastomoses with a protective stoma were excluded. Both open and laparoscopic approaches and both elective and emergency surgeries were allowed.

Data on patient demographics, comorbidities, preoperative parameters, and surgical technique as well as on the postoperative course including anastomotic leakage and morbidity were obtained and analyzed. Primary outcome was the occurrence of anastomotic leakage (see definition below). As secondary outcome influence of suture technique on morbidity (defined by Clavien Dindo [18]), wound healing CDC definition [19]) and re-surgery rate were investigated.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of FAU Erlangen (22–222-Br).

Surgical techniques

All patients received preoperative intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis with a cephalosporin and metronidazole.

All intestinal anastomoses were performed based on three fundamental key points: (1) sufficient mobilization of the intestinal ends to obtain a tension-free anastomosis; (2) preservation of adequate blood perfusion of both intestinal ends; (3) low-bleeding preparation through subtle hemostasis.

Decision about anastomotic technique was made by the surgeon depending on his preference.

-

1.

Interrupted suture technique (IST):

This technique was always performed as single-layered anastomosis with extramucosal inverting stiches using 3/0 polyglactin (Vicryl, Ethicon).

-

2.

Continuous suture technique (CST):

For this technique single and double-layered technique was used. Suture material included 4/0 or 5/0 polydioxanone (PDS, Ethicon) and 4/0 polyglyconate (Maxon, Covidien).

Definition of anastomotic leakage

Postoperative anastomotic leakage of the intestinal anastomosis was defined as the presence of at least one of the following criteria: (1) Evidence of anastomotic leakage by endoscopy; (2) radiological evidence of leakage by contrast-enhanced computer tomography; (3) evidence of leakage during re-surgery.

Statistical analysis

For propensity score matching, the nearest neighbor method to 2:1 ratio was used. Propensity score deviation width was set to a threshold of < 0.2. Variables used for matching were age, gender, and surgically relevant factors: surgical priority and number of anastomosis. Data analysis was performed with SPSS software (SPSS, version 28.0). Comparisons of metric and ordinal data were calculated with the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test. The chi-square test was used for categorical data. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All recorded parameters were tested as potential risk factors for postoperative outcome parameters (morbidity, anastomotic leakage, wound infection, re-surgery) using univariate analysis. Associations with the outcome parameters with a p-value ≤ 0.1 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis.

Results

Demographics

Propensity score matching of the 332 patients (median age: 36 years, 49% female) meeting inclusion criteria revealed 279 matched patients. Of these 279 patients, interrupted suture technique was applied in 183 patients (IST group) and continuous suture technique in 96 patients (CST group). Nine patients of the CST group had only one matched partner in the IST group.

Patients of the IST group had significantly more previous surgeries (1 vs. 0, p = 0.008) and a significantly lower hemoglobin (12.8 vs. 13.4 g/dl, p = 0.042). All other demographic parameters including age, gender, ASA, comorbidities, and preoperative blood results other than hemoglobin did not significantly differ between the groups (Table 1).

Characteristics of Crohn’s disease

At the time of surgery, Crohn’s disease had existed for an average of 7 years. Most patients were diagnosed with Crohn’s disease between the ages of 17 and 40 years (71%). The predominant pattern of Crohn’s disease was an ileocolic location (92%) and a stricturing behavior (77%). Fifty-six percent of the patients were treated with an oral anti-inflammatory and/or immunosuppressive therapy up to 12 weeks before surgery. Comparing Crohn’s characteristics between the suture technique groups, the only difference was that patients of the IST group had significantly more frequent colonic location of Crohn’s disease (40% vs. 22%, p = 0.039) (Table 1).

Surgical parameters

Most patients underwent elective surgery (96%) and one intestinal anastomosis (88%; 226 ileo-colonic anastomosis, 19 colo-colonic anastomosis), whereas 12% received two (16 ileo-colonic + colo-colonic anastomosis, 12 ileo-colonic and small intestine anastomosis and 5 colo-colonic + small intestinine anastomosis) and 1 patient three intestinal anastomosis (colo-colonic + 2 × small intestine anastomosis). Sixty-five percent of all surgeries were performed open and 35% laparoscopically (Table 2). Significant differences between the IST and the CST groups regarding surgical parameters included a significantly more often open approach (79 vs. 38%, p < 0.001) in the IST compared to the CST group (Table 2).

Outcome parameters

Overall morbidity, respectively, mortality in our collective was 35% and, respectively, 0%. Most of the complications were minor complications (63%). Anastomotic leakage occurred in 5% and wound infection in 9%. Six percent of the patients required re-surgery. Reasons for re-surgery were anastomotic leakage (81%), small bowel perforation (13%), and hematoma of the abdominal wall (6%). Median length of postoperative stay was 7 days. Re-admission within 90 days was necessary in 9% of the patients (Table 3).

Primary endpoint analysis

Anastomotic leakage rate did not differ significantly between the two groups (IST: 6% vs. CST: 3%, p = 0.393). Subgroup analysis with stratification of patients according to the surgical approach showed also no significant differences between the two suture technique groups (Table 3). In the univariate analysis, we identified eight risk factors for postoperative anastomotic leakage with a p-value ≤ 0.1 (higher ASA score, p < 0.001; higher number of previous surgeries, p = 0.003; age > 40 years at Crohn’s diagnosis, p = 0.043; increase of preoperative CRP, p = 0.046; emergency surgery, p = 0.081; open surgical approach, p = 0.054; higher number of anastomosis, p = 0.085; increase of operative time, p = 0.029). Among these variables, only an ASA score of III/IV (OR 5.32 (95% CI = 1.22–23.18), p = 0.026) was confirmed as independent risk factors for the development of anastomotic leakage in the multivariate analysis (Table 4).

Secondary endpoint analysis

In univariate analysis, in-hospital-morbidity was significantly lower in the CST-group compared to the IST-group (CST: 26% vs. IST: 39%, p = 0.034). Stratified according to the Clavien Dindo classification, in-hospital morbidity did not differ between the groups (p = 0.294). Wound infection rate as well as the rate of re-surgery did not differ between the two groups (p = 0.280, respectively, p = 0.062) (Table 3).

In multivariate analysis, the suture technique could not be confirmed as independent risk factor for morbidity (OR 1.44 (95% CI = 0.74–2.81, p = 0.288). Independent risk factors for morbidity were a lower preoperative hemoglobin (OR 0.85 (95% CI = 0.73–0.99), p = 0.036) and a longer operative time (OR 1.01 (95% CI = 1.00–1.01), p = 0.003). A higher number of previous surgeries could be identified as an independent risk factors for wound infection (OR 1.36 (95% CI = 1.07–1.73), p = 0.013). There were two independent risk factors for the need for re-surgery: an ASA score of III/IV (OR 4.34 (95% CI = 1.15–16.46), p = 0.031) and a longer operative time (OR 1.01 (95% CI = 1.00–1.02), p = 0.020) (Table 4).

Discussion

The surgical technique represents a decisive component for safe performance of intestinal anastomosis. Well-known surgical principles to prevent anastomotic leakage are gentle tissue handling, good hemostasis, adequate blood perfusion, asepsis, and a tension-free anastomosis. However, the evidence regarding interrupted versus continuous suture technique for intestinal anastomosis is insufficient.

The present study revealed no difference regarding the anastomotic leakage rate when comparing the interrupted and the continuous suture technique in the high-risk population of patients with Crohn’s disease. This result is in line with one of two existing previous studies with the same study endpoint. This study of Deen and Smart from 1995 was able to demonstrate an insufficiency rate of 3.8% and 3.7% for the interrupted and continuous suture technique, respectively, but in a clearly limited sample size of 57 patients [17]. In contrast, a more recent analysis of Eickhoff et al. from 2018 included 347 patients and could reveal a significant influence of the suture technique on anastomotic leakage showing a fivefold increased risk for anastomotic leakage using the interrupted suture technique (IST: 16% vs. CST: 2.5%, p = 0,001) [10]. However, one possible explanation for these ambiguous results might be the quite high anastomotic leakage rate of 16%, clustered especially in the group of interrupted suture technique, which the authors of the study have already mentioned as non-ideal anastomosis outcome.

In our cohort, the overall anastomotic leakage rate was 5% and is therefore in the range of those reported in the literature in which leakage rates vary between 1 and 10% for patients with different indications for surgery [6,7,8, 10, 11, 20,21,22,23,24,25]. Regarding patients with Crohn’s disease, an analysis of 463 patients with ileocolonic anastomosis using continuous suture technique by Volk et al. showed a leakage rate of 4.3% in this subgroup [8]. Repeated intestinal resection in patients with Crohn’s disease was associated with an increased rate of anastomotic leakage [24].

In our hospital, experiences with both techniques originate from different surgical schools. This fact could be a possible explanation for our result and may underline the importance of surgical school in intestinal anastomosis. Again, this suggests that surgeons should choose the technique with which they are used to and are more comfortable.

The only identified independent risk factor for anastomotic leakage in our cohort was the ASA score. This is in line with previous reports [6, 11, 20]. Moreover, in literature there are several other identified risk factors such as urgent operation setting, a body mass index > 25 kg/m2, diabetes mellitus, a hypotensive circulation upon admission, preoperative leukocytosis, intraoperative septic conditions, difficulties encountered during anastomosis, colocolic anastomosis, higher intraoperative blood loss, and postoperative blood transfusion [7, 8, 22, 23]. Some of these risk factors could not be confirmed, and some were not investigated in our study.

Secondary endpoint analysis showed that the suture technique has no relevant influence on morbidity, on wound infection rate as well as re-surgery rate in multivariate analysis. The significant association of morbidity with the suture technique in univariate analysis may be explained by the significant more often use of laparoscopic approach in continuous suture technique, which is known to be associated with less morbidity. The lack of impact of the suturing technique on the occurrence of wound infections was also demonstrated in the already mentioned study by Eickhoff et al. [10].

In our study, independent risk factors for morbidity were lower preoperative hemoglobin and longer operative time; for wound infection, a higher number of previous surgeries; and for re-surgery, an ASA score of III/IV and a longer operative time. All these are already reported risk factors in literature [8].

Our study is the first analysis using a propensity score matched cohort, which might be a relevant strength for homogenization of patient cohorts. Moreover, we selected the high risk population of patients with Crohn’s disease, which again leads to a homogenization of the patient population and gives our results additional relevance due to the increased insufficiency rates in this patient population. However, the present study has several limitations. First, the retrospective design of our study may have incurred some bias. Second, the patient cohort is heterogeneous regarding the surgical approach. Subsequently, the differences in univariate analysis for morbidity may be affected by the extended trauma in open surgery. However, the surgical approach was included to the multivariate analysis, so that a potential influence of this factor was taken into account.

Conclusion

Our results show that in experienced hands, both the interrupted and the continuous suture technique can be performed with equal safety. Randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm these findings.

References

Ellis CT, Maykel JA (2021) Defining anastomotic leak and the clinical relevance of leaks. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 34(6):359–365. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1735265

Fouda E, El Nakeeb A, Magdy A, Hammad EA, Othman G, Farid M (2011) Early detection of anastomotic leakage after elective low anterior resection. J Gastrointest Surg 15(1):137–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-010-1364-y

Hammond J, Lim S, Wan Y, Gao X, Patkar A (2014) The burden of gastrointestinal anastomotic leaks: an evaluation of clinical and economic outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg 18(6):1176–1185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2506-4

Thornton M, Joshi H, Vimalachandran C, Heath R, Carter P, Gur U, Rooney P (2011) Management and outcome of colorectal anastomotic leaks. Int J Colorectal Dis 26(3):313–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-010-1094-3

Temple LK, Bacik J, Savatta SG, Gottesman L, Paty PB, Weiser MR, Guillem JG, Minsky BD, Kalman M, Thaler HT, Schrag D, Wong WD (2005) The development of a validated instrument to evaluate bowel function after sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 48(7):1353–1365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-004-0942-z

Alves A, Panis Y, Trancart D, Regimbeau JM, Pocard M, Valleur P (2002) Factors associated with clinically significant anastomotic leakage after large bowel resection: multivariate analysis of 707 patients. World J Surg 26(4):499–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-001-0256-4

Lipska MA, Bissett IP, Parry BR, Merrie AE (2006) Anastomotic leakage after lower gastrointestinal anastomosis: men are at a higher risk. ANZ J Surg 76(7):579–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03780.x

Volk A, Kersting S, Held HC, Saeger HD (2011) Risk factors for morbidity and mortality after single-layer continuous suture for ileocolonic anastomosis. Int J Colorectal Dis 26(3):321–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-010-1040-4

Neary PM, Aiello AC, Stocchi L, Shawki S, Hull T, Steele SR, Delaney CP, Holubar SD (2019) High- risk ileocolic anastomoses for Crohn’s disease: when is diversion indicated? J Crohns Colitis 13(7):856–863. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz004

Eickhoff R, Eickhoff SB, Katurman S, Klink CD, Heise D, Kroh A, Neumann UP, Binnebösel M (2019) Influence of suture technique on anastomotic leakage rate-a retrospective analyses comparing interrupted-versus continuous-sutures. Int J Colorectal Dis 34(1):55–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-018-3168-6

McDermott FD, Heeney A, Kelly ME, Steele RJ, Carlson GL, Winter DC (2015) Systematic review of preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative risk factors for colorectal anastomotic leaks. Br J Surg 102(5):462–479. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9697

Zurbuchen U, Kroesen AJ, Knebel P, Betzler MH, Becker H, Bruch HP, Senninger N, Post S, Buhr HJ, Ritz JP, German Advanced Surgical Treatment Study Group (2013) Complications after end-to-end vs. side-to-side anastomosis in ileocecal Crohn’s disease--early postoperative results from a randomized controlled multi-center trial (ISRCTN-45665492). Langenbecks Arch Surg 398(3):467–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-012-0904-1

Herrle F, Diener MK, Freudenberg S, Willeke F, Kienle P, Boenninghoff R, Weiss C, Partecke LI, Schuld J, Post S (2016) Single-layer continuous versus double-layer continuous suture in colonic anastomoses-a randomized multicentre trial (ANATECH Trial). J Gastrointest Surg 20(2):421–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-015-3003-0

Gustafsson P, Jestin P, Gunnarsson U, Lindforss U (2015) Higher frequency of anastomotic leakage with stapled compared to hand-sewn ileocolic anastomosis in a large population-based study. World J Surg 39(7):1834–1839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-015-2996-6

Slieker JC, Daams F, Mulder IM, Jeekel J, Lange JF (2013) Systematic review of the technique of colorectal anastomosis. JAMA Surg 148(2):190–201. https://doi.org/10.1001/2013.jamasurg.33

Delaitre B, Champault G, Chapuis Y, Patel JC, Louvel A, Leger L (1977) Sutures intestinales par surjets et points séparés. Etude expérimentale et clinique [Continuous and interrupted intestinal sutures. Experimental and clinical study (author's transl)]. J Chir (Paris) 113(1):43–57. French.

Deen KI, Smart PJ (1995) Prospective evaluation of sutured, continuous, and interrupted single layer colonic anastomoses. Eur J Surg 161(10):751–753

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240(2):205–213. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae

Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG (1992) CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Am J Infect Control 20(5):271–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0196-6553(05)80201-9

Buchs NC, Gervaz P, Secic M, Bucher P, Mugnier-Konrad B, Morel P (2008) Incidence, consequences, and risk factors for anastomotic dehiscence after colorectal surgery: a prospective monocentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis 23(3):265–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-007-0399-3

Telem DA, Chin EH, Nguyen SQ, Divino CM (2010) Risk factors for anastomotic leak following colorectal surgery: a case-control study. Arch Surg 145(4):371–376; discussion 376. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2010.40

Leichtle SW, Mouawad NJ, Welch KB, Lampman RM, Cleary RK (2012) Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 55(5):569–575. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182423c0d

Morse BC, Simpson JP, Jones YR, Johnson BL, Knott BM, Kotrady JA (2013) Determination of independent predictive factors for anastomotic leak: analysis of 682 intestinal anastomoses. Am J Surg 206(6):950–955; discussion 955–956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.07.017

Johnston WF, Stafford C, Francone TD, Read TE, Marcello PW, Roberts PL, Ricciardi R (2017) What is the risk of anastomotic leak after repeat intestinal resection in patients with Crohn's disease? Dis Colon Rectum 60(12):1299–1306. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000946

Midura EF, Hanseman D, Davis BR, Atkinson SJ, Abbott DE, Shah SA, Paquette IM (2015) Risk factors and consequences of anastomotic leak after colectomy: a national analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 58(3):333–338. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000249

Acknowledgements

The present work was performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for obtaining the degree "Dr. med" for Tobias von Loeffelholz.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Georg F. Weber and Maximilian Brunner; investigation: Tobias Loeffelholz and Maximilian Brunner; resources: Robert Grützmann; data curation: Tobias Loeffelholz and Maximilian Brunner; writing — original draft preparation: Anke Mittelstädt and Maximilian Brunner; writing — review and editing: Anke Mittelstädt, Tobias Loeffelholz, Klaus Weber, Axel Denz, Christian Krautz, Robert Grützmann, Georg F. Weber, and Maximilian Brunner; supervision: Georg F. Weber and Maximilian Brunner. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Statement of human rights

For this type of study, formal consent is not required. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of FAU Erlangen (22-222-Br).

Statement on the welfare of animals

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This study contains no information that would enable individual patient identity.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mittelstädt, A., von Loeffelholz, T., Weber, K. et al. Influence of interrupted versus continuous suture technique on intestinal anastomotic leakage rate in patients with Crohn’s disease — a propensity score matched analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 37, 2245–2253 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-022-04252-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-022-04252-1