Abstract

Background and aims

The ileoanal pouch (IPAA) provides patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) that have not responded to medical therapy an option to retain bowel continuity and defecate without the need for a long-term stoma. Despite good functional outcomes, some pouches fail, requiring permanent diversion, pouchectomy, or a redo pouch. The incidence of pouch failure ranges between 2 and 15% in the literature. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis aiming to define the prevalence of pouch failure in patients with UC who have undergone IPAA using population-based studies.

Methods

We searched Embase, Embase classic and PubMed from 1978 to 31st of May 2021 to identify cross-sectional studies that reported the prevalence of pouch failure in adults (≥ 18 years of age) who underwent IPAA for UC.

Results

Twenty-six studies comprising 23,389 patients were analysed. With < 5 years of follow-up, the prevalence of pouch failure was 5% (95%CI 3–10%). With ≥ 5 but < 10 years of follow-up, the prevalence was 5% (95%CI 4–7%). This increased to 9% (95%CI 7–16%) with ≥ 10 years of follow-up. The overall prevalence of pouch failure was 6% (95%CI 5–8%).

Conclusions

The overall prevalence of pouch failure in patients over the age of 18 who have undergone restorative proctocolectomy in UC is 6%. These data are important for counselling patients considering this operation. Importantly, for those patients with UC being considered for a pouch, their disease course has often resulted in both physical and psychological morbidity and hence providing accurate expectations for these patients is vital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) is considered to be the gold standard surgical treatment for ulcerative colitis (UC) that is refractory to medical therapy [1]. Several iterations have been described in the literature following its introduction in 1978 by Parks and Nicholls [2]. Ultimately, IPAA involves resection of the diseased colon and rectum and restoration of bowel continuity, allowing the patient to defecate without the need of an ileostomy. This in turn has been shown to improve patients’ quality of life [3]. The value of such a procedure cannot be understated when considering that one fifth of patients with UC will need surgical intervention with a colectomy rate of 16% after a disease duration of 10 years [4].

Despite good functional outcomes, serious complications such as pelvic sepsis, strictures, anastomotic leaks, de novo Crohn’s disease, pouchitis and persistent pouch dysfunction can occur. These are known risk factors for pouch failure, defined as the need for pouch resection, permanent diversion, or a redo pouch. Several risk factors for pouch failure have been documented in the literature, the commonest being pelvic sepsis [5]. Chronic pouchitis and fistulas have also been associated with pouch failure. Primary sclerosing cholangitis can increase pouchitis rates as well as the risk of postoperative sepsis [6]. Reported failure rates vary significantly in the literature, ranging from 2 to 15% [7, 8]. When compared to a permanent ileostomy, a viable alternative, IPAA has been shown to improve patients’ perceptions of their body image and has similar effects on quality of life [9]. Despite this, IPAA has a higher complication rate [10]. A vital component of informed decision making and managing expectations is being able to accurately convey the likelihood of complications such as pouch failure occurring for a given intervention. Furthermore, understanding the prevalence of pouch failure and how this changes over time can help identify and manage complications which have the potential to cause pouch failure.

Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis aiming to define the prevalence of pouch failure in patients with UC exclusively who have undergone IPAA using population-based studies.

Methods

We searched Embase, Embase classic and PubMed from 1978 to 31st of May 2021 to identify population-based studies (cross-sectional, case control and cohort) that reported the prevalence of pouch failure in adults (≥ 90% of the population), age 18 years and above who underwent IPAA for UC exclusively. Pouch failure was defined as the need for permanent diversion and/or pouchectomy and/or a redo pouch. Short-term outcomes have been reported extensively in the literature [11]. Therefore, we only included studies with a minimum of 1-year follow-up. To minimise the risk of selection bias, we excluded studies with a small sample size (< 200 patients). We hand-searched the references from eligible studies and the proceedings from inflammatory bowel disease conferences (United European Gastroenterology, European Crohn’s and Colitis Society, British Society of Gastroenterology and Digestive Disease week) up until May 2021. We searched the medical literature using the terms provided in Supplementary Table 1, using them as medical subject headings [MeSH] and free-text terms. No language restrictions were implemented. We manually searched references from eligible studies for any further studies to included. For studies that appeared to be eligible for inclusion but did not have sufficient data, we attempted to contact the authors for clarification.

Data were extracted by two independent reviewers (ZA, AS) using Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. The extracted data is provided in Supplementary Table 2. All disagreements went to a third reviewer (JPS) for a consensus. The following data were extracted for each study: country, number of patients providing complete data, type of study, year of study, reason for pouch failure, total number of patients, number of patients with pouch failure, mean/median follow-up (rounded to the nearest year), number of failed IPAA at various timepoints.

We combined the proportion of patients with pouch failure in each study to give a pooled prevalence for each study. We then performed a random effects model to pool the data and provide an estimate of the prevalence of pouch failure.

We assessed the quality of case–control studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale, with a total possible score of 9 (higher scores indicating higher quality studies). Sensitivity analysis was performed using the one-study remove method to detect the impact of each study on the combined effect. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot inspection and Egger’s test. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. All statistics were performed using R with the package “meta.”

This review is presented in line with the PRISMA guidelines and was registered priori on Prospero (CRD42021259505).

Results

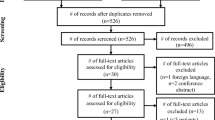

Two thousand six hundred and twenty-two studies were identified in the search. Twenty-six cohort studies (5 prospective cohort studies and 21 retrospective cohort studies) met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis [1, 5, 7, 8, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Data were extracted from the 26 articles comprising 23,389 patients with UC who underwent IPAA (Fig. 1).

With < 5 years of follow-up, the prevalence of pouch failure was 5% (95%CI 3–10%). With ≥ 5 but < 10 years of follow-up, the prevalence was 5% (95%CI 4–7%). This increased to 9% (95%CI 7–16%) with ≥ 10 years of follow-up. The overall prevalence of pouch failure was 6% (95%CI 5–8%) (Fig. 2). However, the studies demonstrated a significant amount of heterogeneity at each time frame (< 5 years (I2 = 89%, P < 0.01), ≥ 5 but < 10 (I2 = 91%, P < 0.01), ≥ 10 years (I2 = 97%, P < 0.01) and overall prevalence of pouch failure (I2 = 95%, P < 0.01)). Using Egger’s test, no funnel plot asymmetry was observed when assessing studies with < 5 years and ≥ 5 but < 10 years of follow-up (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Due to the lack of data, it was not possible to perform Egger’s test on studies with ≥ 10 years of follow-up. Despite this, no asymmetry is observed on visual inspection of the graph (Supplementary Fig. 3). The year in which a study was published (1978–2021) did not have a significant impact on pouch failure rates (R2 = 5.12%, P = 0.2477) (Fig. 3).

Using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale and AHRQ standards, 19 studies were classified as poor while 7 were deemed to be good (Table 1).

Nine articles reported causes of pouch failure, the most common being fistulae (n = 72). Other reported causes of pouch failure include pouchitis (n = 33), strictures (n = 20), Crohn’s disease (n = 45), surgical complications (n = 6) and pelvis sepsis (n = 1). Four articles reported failure rates at multiple time points (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis with systematic review that defines the prevalence of pouch failure in patients exclusively with UC. Our data suggests that the overall prevalence of pouch failure is 6%. Recent meta-analyses by Heuthorst et al. [34] and Emile et al. [35] report pouch failure rates of 7.7% and 7.5%, respectively. However, these studies also assessed patients with intermediate colitis, cancer and Crohn’s disease along with UC which may have a compounding detrimental effect on pouch outcomes. Prior studies have shown that complications predominantly occur within the first few months of surgery [36]. This suggested that the IPAA may withstand the test of time with a relatively stable failure rate. This is echoed by Lorenzo et al. [11], who found that despite slightly worsening function over a period of 20 years, failure rates remained stable while quality of life measurements remained high. However, there are relatively few studies that provide long follow-up periods, with only 7 articles in our meta-analysis following patient for ≥ 10 years. This would have added another dimension to our understanding of pouch failure, particularly with there being a suggestion of increasing failure rates with time [36, 37]. Despite this, our analysis did not show any evidence of publication bias.

Our results show that the year of publication did not affect pouch failure rates. This is despite several advancements to the procedure in recent years such as the advent different pouch designs and the introduction of the laparoscopic and robotic approaches [38, 39]. Although not specifically investigated in our study, there is evidence to suggest that these advancements have not only led to faster recovery times and progression to restoration of intestinal continuity, but have also led to better functional outcomes over time which have been reported to have a positive impact on patients’ quality of life [3, 38, 40, 41]. This may prove to be useful when counselling patients on the risks and benefits of the procedure.

Additionally, the analysis demonstrated significant heterogeneity overall, and in each follow-up period. This could reflect the differences in study design, follow-up periods, baseline patient characteristics, type of IPAA performed and type of centre the procedure was performed in. It is also worth considering the differences in practice between countries and how this may impact the management of UC as a whole.

Several causes of pouch failure were cited in the literature such as Crohn’s disease, pouchitis, fistulae, pelvic sepsis and leaks. Additionally, several risk factors for pouch failure have been identified such as male gender, high BMI, advanced age and extraintestinal manifestation of UC such as erythema nodosum [42]. However, only a few studies reported the exact figures, making it difficult to ascertain the correlation between the complications and pouch failure. Heuthorst et al. [34] showed that the pouch failure was significantly correlated with fistulae and pelvic sepsis. Of note, the study included patients with Crohn’s disease, indeterminate colitis, familial adenomatous polyposis, and colorectal cancer along with UC. Nonetheless, it may be used to guide future follow-up. The aim of this study was to provide an estimate of the prevalence of pouch failure in patients with UC. This may guide future studies and power calculations. We excluded studies where pouches were originally constructed for CD as the literature suggests that they have a higher incidence of failure and was deemed to be a relative contraindication [43] Additionally, significant differences exist in the definition and terminology used when discussing CD of the pouch which may result in its overdiagnosis [44]. Therefore, including these studies may have skewed our results. We also excluded studies assessing patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis as it is known to have a significant impact on pouch failure and would also skew the results [45]. The lack of a definition has resulted in large discrepancies in the reported incidence of pouch failure secondary to CD and may benefit from a metanalysis of its own.

This is the first meta-analysis evaluating the literature from the inception of IPAA to May 2021. The large sample size of 23,389 patients allowed us to give a comprehensive estimate of the prevalence of pouch failure in UC. Our bubble plot shows that the year of publication did not have a significant effect on pouch failure rates, allowing us to include all eligible studies from 1978 to 2021. Furthermore, we assessed how failure rates change over time which would assist patients in making informed decisions. Additionally, we excluded studies with small sample sizes to minimise the risk of selection bias.

Limitations of this study should also be noted. Firstly, the studies included are observational in nature with no prospective randomised studies being available. This, however, is unavoidable in view of these being the mainstay of available evidence in this area. Secondly, most studies included were performed on western populations which may impact the article’s generalisability. As our aims were to assess overall pouch failure, we examined studies looking at whole UC populations and excluded articles looking at specific surgical techniques. Additionally, we attempted to evaluate the prevalence of pouch failure at multiple time points to provide granularity. Unfortunately, most of the studies that met our inclusion criteria did not report failure at multiple time points and yielded insufficient data to allow for meaningful analysis. Several articles cited CD as a cause of pouch failure despite operating on patients with UC exclusively. Additionally, fistulae may have occurred secondary to CD as well as surgical complications and ischaemia. In an ideal situation, we would have reanalysed the data, excluding patients with a postoperative diagnosis of CD. Unfortunately, the data lacked granularity and proved to be insufficient when undertaking any meaningful analyses.

Future studies should aim to report the causes of pouch failure using established definitions at various timepoints. This would allow us to find optimal follow-up periods, monitoring modalities and management plans in order to minimise the risk of pouch failure.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of patients with UC who underwent IPAA demonstrates an overall prevalence of pouch failure of 6%. Despite the intricacies of the subject matter, the question of pouch failure is an important one to address, with these data being particularly important for counselling patients considering the procedure. Importantly, for those patients with UC being considered for a pouch, their disease course has often resulted in both physical and psychological morbidity and hence providing accurate expectations is vital.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

Code availability

Available on request by emailing corresponding author.

References

Jackson KL, Stocchi L, Duraes L, Rencuzogullari A, Bennett AE, Remzi FH (2017) Long-term outcomes in indeterminate colitis patients undergoing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: function, quality of life, and complications. J Gastrointest Surg 21(1):56–61

Parks AG, Nicholls RJ (1978) Proctocolectomy without ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. Br Med J 2(6130):85–88

Heikens JT, de Vries J, Goos MR, Oostvogel HJ, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ (2012) Quality of life and health status before and after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg 99(2):263–269

Kühn F, Klar E (2015) Surgical principles in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Viszeralmedizin 31(4):246–250

Uchino M, Ikeuchi H, Sugita A, Futami K, Watanabe T, Fukushima K et al (2018) Pouch functional outcomes after restorative proctocolectomy with ileal-pouch reconstruction in patients with ulcerative colitis: Japanese multi-center nationwide cohort study. J Gastroenterol 53(5):642–651

Deputy M, Segal J, Reza L, Worley G, Costello S, Burns E et al (2021) The pouch behaving badly: management of morbidity after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Colorectal Dis 23(5):1193–1204

Dayton MT, Larsen KR, Christiansen DD (2002) Similar functional results and complications after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in patients with indeterminate vs ulcerative colitis. Arch Surg 137(6):690–695

Mark-Christensen A, Erichsen R, Brandsborg S, Pachler FR, Nørager CB, Johansen N et al (2018) Pouch failures following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis 20(1):44–52

Murphy PB, Khot Z, Vogt KN, Ott M, Dubois L (2015) Quality of life after total proctocolectomy with ileostomy or IPAA: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum 58(9):899–908

Camilleri-Brennan J, Munro A, Steele RJ (2003) Does an ileoanal pouch offer a better quality of life than a permanent ileostomy for patients with ulcerative colitis? J Gastrointest Surg 7(6):814–819

Lorenzo G, Maurizio C, Maria LP, Tanzanu M, Silvio L, Mariangela P et al (2016) Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis 20 years later: is it still a good surgical option for patients with ulcerative colitis? Int J Colorectal Dis 31(12):1835–1843

Olecki E, Kronfli AP, Stahl KA, King S, Razavai N, Koltun W, Hershey PA (2021) Stoma-less ileal-pouch-anal-anastomosis is not associated with increased long-term pouch failure rates in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum Conf: Am Soc Colon Rectal Surg Ann Sci Meet 7–38

Erondu A, Akiyama S et al (2020) Time trend analysis of pre-operative characteristics and post-operative pouch outcomes in UC patients undergoing ileal pouch anal-anastomosis: S0777. Am J Gastroenterol

Lavryk OA, Stocchi L, Hull TL, Lipman JM, Shawki S, Holubar SD et al (2020) Impact of preoperative duration of ulcerative colitis on long-term outcomes of restorative proctocolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 35(1):41–49

Lee GC, Deery SE, Kunitake H, Hicks CW, Olariu AG, Savitt LR et al (2019) Comparable perioperative outcomes, long-term outcomes, and quality of life in a retrospective analysis of ulcerative colitis patients following 2-stage versus 3-stage proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Int J Colorectal Dis 34(3):491–499

Skowron KDL, Rubin M, Hurst R, Fichera A, Umanskiy K (2012) J-pouch outcomes in ulcerative colitis are not affected by preoperative administration of biologic agents. Am Soc Colon Rectal Surg Ann Meet Abstracts

Lepistö A, Kärkkäinen P, Järvinen HJ (2008) Prevalence of primary sclerosing cholangitis in ulcerative colitis patients undergoing proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 14(6):775–779

Nordenvall C, Westberg K, Söderling J, Everhov ÅH, Halfvarson J, Ludvigsson JF et al (2021) Restorative surgery is more common in ulcerative colitis patients with a high income: a population-based study. Dis Colon Rectum 64(3):301–312

Helavirta I, Lehto K, Huhtala H, Hyöty M, Collin P, Aitola P (2020) Pouch failures following restorative proctocolectomy in ulcerative colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis 35(11):2027–2033

Landerholm K, Abdalla M, Myrelid P, Andersson RE (2017) Survival of ileal pouch anal anastomosis constructed after colectomy or secondary to a previous ileorectal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis patients: a population-based cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol 52(5):531–535

Helavirta I, Huhtala H, Hyöty M, Collin P, Aitola P (2015) Restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis in 1985–2009. Scand J Surg 105(2):73–77

Mukewar S, Wu X, Lopez R, Bo S (2014) Comparison of long-term outcomes of S and J pouches and continent ileostomies in ulcerative colitis patients with restorative proctocolectomy-experience in subspecialty pouch center ✩. J Crohns Colitis 8(10):1227–1236

Nieminen I, Huhtala H, Hyöty M, Collin P, Aitola P (2013) P346 The experience of restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis during 1985–2009. J Crohns Colitis 7(Supplement_1):S148-S

Keighley MR (2000) The final diagnosis in pouch patients for presumed ulcerative colitis may change to Crohn’s disease: patients should be warned of the consequences. Acta Chir Iugosl 47(4 Suppl 1):27–31

Delaney CP, Remzi FH, Gramlich T, Dadvand B, Fazio VW (2002) Equivalent function, quality of life and pouch survival rates after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for indeterminate and ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg 236(1):43–48

Heuschen U, Schmidt J, Allemeyer E, Stern J, Heuschen G (2001) The ileo-anal pouch procedure: Complications, quality of life, and long-term results. Zentralbl Chir 126(Suppl 1):36–42

Fazio VW, Kiran RP, Remzi FH, Coffey JC, Heneghan HM, Kirat HT et al (2013) Ileal pouch anal anastomosis: analysis of outcome and quality of life in 3707 patients. Ann Surg 257(4):679–685

Berndtsson I, Lindholm E, Oresland T, Börjesson L (2007) Long-term outcome after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: function and health-related quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum 50(10):1545–1552

Arai K, Koganei K, Kimura H, Akatani M, Kitoh F, Sugita A et al (2005) Incidence and outcome of complications following restorative proctocolectomy. Am J Surg 190(1):39–42

Farouk R, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, Dozois RR, Browning S, Larson D (2000) Functional outcomes after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg 231(6):919–926

Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, Oakley JR, Lavery IC, Milsom JW et al (1995) Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg 222(2):120–127

Pemberton JH, Kelly KA, Beart RW Jr, Dozois RR, Wolff BG, Ilstrup DM (1987) Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Long-term results Ann Surg 206(4):504–513

MacRae HM, McLeod RS, Cohen Z, O’Connor BI, Ton EN (1997) Risk factors for pelvic pouch failure. Dis Colon Rectum 40(3):257–262

Heuthorst L, Wasmann KATGM, Reijntjes MA, Hompes R, Buskens CJ, Bemelman WA (2021) Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis complications and pouch failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Open 2(2):e074

Emile SH, Gilshtein H, Wexner SD (2020) Outcome of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with indeterminate colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis 14(7):1010–1020

Leowardi C, Hinz U, Tariverdian M, Kienle P, Herfarth C, Ulrich A et al (2010) Long-term outcome 10 years or more after restorative proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 395(1):49–56

Tulchinsky H, Hawley PR, Nicholls J (2003) Long-term failure after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg 238(2):229–234

McCormick PH, Guest GD, Clark AJ, Petersen D, Clark DA, Stevenson AR et al (2012) The ideal ileal-pouch design: a long-term randomized control trial of J- vs W-pouch construction. Dis Colon Rectum 55(12):1251–1257

Flynn J, Larach JT, Kong JCH, Warrier SK, Heriot A (2021) Robotic versus laparoscopic ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 36(7):1345–1356

Beyer-Berjot L, Maggiori L, Birnbaum D, Lefevre JH, Berdah S, Panis Y (2013) A total laparoscopic approach reduces the infertility rate after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a 2-center study. Ann Surg 258(2):275–282

Fajardo AD, Dharmarajan S, George V, Hunt SR, Birnbaum EH, Fleshman JW et al (2010) Laparoscopic versus open 2-stage ileal pouch: laparoscopic approach allows for faster restoration of intestinal continuity. J Am Coll Surg 211(3):377–383

Frese JP, Gröne J, Lauscher JC, Konietschke F, Kreis ME, Seifarth C (2021) Risk factors for failure of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with refractory ulcerative colitis. Surgery

Barnes EL, Kochar B, Jessup HR, Herfarth HH (2019) The incidence and definition of Crohn’s disease of the pouch: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 25(9):1474–1480

Lightner AL, Fletcher JG, Pemberton JH, Mathis KL, Raffals LE, Smyrk T (2017) Crohn’s disease of the pouch: a true diagnosis or an oversubscribed diagnosis of exclusion? Dis Colon Rectum 60(11):1201–1208

Barnes EL, Holubar SD, Herfarth HH (2021) Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 15(8):1272–1278

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JPS conceptualized the study. JPS, ZA, and AS conducted the literature review, performed the data extraction, and drafted the manuscript. JPS performed the analysis. All authors agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

JPS has received speaker fees for Janssen, Abbvie, and Takeda. Guarantor of article Jonathan P Segal (Jonathansegal1@nhs.net).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsafi, Z., Snell, A. & Segal, J.P. Prevalence of ‘pouch failure’ of the ileoanal pouch in ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 37, 357–364 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-021-04067-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-021-04067-6