Abstract

Objective

Heterotopic pancreas, an uncommon condition in children, can present with diagnostic and treatment challenges. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical features and treatment options for this disorder in pediatric patients.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis, including patients diagnosed with heterotopic pancreas at four tertiary hospitals between January 2000 and June 2022. Patients were categorized into symptomatic and asymptomatic groups based on clinical presentation. Clinical parameters, including age at surgery, lesion size and site, surgical or endoscopic approach, pathological findings, and outcome, were statistically analyzed.

Results

The study included 88 patients with heterotopic pancreas. Among them, 22 were symptomatic, and 41 were aged one year or younger. The heterotopic pancreas was commonly located in Meckel’s diverticulum (46.59%), jejunum (20.45%), umbilicus (10.23%),ileum (7.95%), and stomach (6.82%). Sixty-six patients had concomitant diseases. Thirty-three patients had heterotopic pancreas located in the Meckel’s diverticulum, with 80.49% of cases accompanied by gastric mucosa heterotopia (GMH). Patients without accompanying GMH had a higher prevalence of heterotopic pancreas-related symptoms (75%). Treatment modalities included removal of the lesions by open surgery, laparoscopic or laparoscopic assisted surgery, or endoscopic surgery based on patient’s age, the lesion site and size, and coexisting diseases.

Conclusions

Only one-fourth of the patients with heterotopic pancreas presented with symptoms. Those located in the Meckel’s diverticulum have commonly accompanying GMH. Open surgical, laparoscopic surgical or endoscopic resection of the heterotopic pancreas is recommended due to potential complications. Future prospective multicenter studies are warranted to establish rational treatment options.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pancreatic tissues located at unusual sites, exhibiting histological structures similar to those of normal pancreas, yet lacking anatomical relation to the normal pancreas, and direct blood vessel connections to the normal pancreas are termed “heterotopic pancreas, aberrant pancreas, or ectopic pancreas” [1, 2]. Its pathogenesis is attributed to abnormal developmental regulatory mechanisms [3]. Heterotopic pancreas can be found in various locations, including the stomach, duodenum, jejunum, Meckel’s diverticulum, duplication or other sites [4, 5]. While heterotopic pancreas often remains asymptomatic and is incidentally detected during gastroscopy or abdominal surgery for other unrelated causes [6], it can manifest with symptoms such as acute or chronic inflammation, bleeding, and intestinal obstruction [4, 5]. Moreover, reports exist of malignant transformation to adenocarcinoma or acinar cell carcinoma originating from heterotopic pancreas [7]. The diagnosis and optimal treatment of this condition pose challenges for clinicians in the pediatric population [8, 9]. The aim of this study was to explore the clinical features and treatment options for heterotopic pancreas in children.

Materials and methods

Electronic medical records of pediatric patients with pathologically confirmed heterotopic pancreas were retrospectively collected from four tertiary hospitals between January 2000 and June 2022, using the search terms ‘‘ectopic pancreas, heterotopic pancreas, and/or adenomyoma”.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with confirmed pancreatic tissue in other sites without any connection with the normal pancreas (2) patients aged ≤ 18 years with symptom onset related to heterotopic pancreas or incidentally found due to other abdominal surgery or endoscopy screeningand (3) pathologically confirmed diagnosis. The exclusion criteria included patients aged > 18 years with symptom onset of heterotopic pancreas, and patients with a suspected diagnosis of heterotopic pancreas that was not confirmed pathologically.

Clinical data, including sex, age, clinical presentation, lesion size and site, coexisting diseases, treatment approach, Heinrich pathological type, and occurrence of intra- and postoperative complications were collected. Patients with symptoms strongly associated with heterotopic pancreas were considered symptomatic, whereas those whose lesions were incidentally found in other diseases were considered asymptomatic. Patients presenting with symptoms due to the mechanical causes of Meckel’s diverticulum or duplication cysts were classified as asymptomatic [5, 10].

Regarding pathological evaluation, sections were reviewed by senior pathologists from their hospitals and categorized into three types based on the Heinrich classification [1, 6, 11]. Briefly, type I consists of three components: pancreatic acini, ducts, and islet cellstype II is composed of acini and pancreatic ductsand type III contains only pancreatic ducts. Gastrointestinal adenomyomas, consisting of ducts and smooth muscle bundles, are categorized as type III [11, 12].

The patients were divided into symptomatic and asymptomatic groups based on their clinical presentation. Categorical variables are shown as numbers and percentages and were statistically analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University Hospital (No. 20210120-01). Written informed consent for the use of their data for scientific purposes was obtained from the parents/legal guardians (s) of all children involved in the study.

Results

Eighty-eight patients with pathologically confirmed heterotopic pancreas met the inclusion criteria. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The results indicate that 41 (46.59%) patients were aged 1 year or younger, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.84:1. Twenty-two patients (25%) exhibited symptoms related to a heterotopic pancreas. The lesions were predominantly found in the Meckel’s diverticulum (46.59%), jejunum (20.45%), ileum (7.96%), stomach (6.82%), and umbilicus (10.23%). Three-fourths of the patients had comorbidities such as gastrointestinal bleeding, intussusception, omphalomesenteric duct anomalies, jejunal or ileal atresia/stenosis, and acute abdomen (malrotation with gut volvulus, appendicitis, and intestinal perforations).

Eighty-two cases (93.18%) were classified as Heinrich type I, while three (3.41%) as type II, and two (2.27%) as type III. There was no evidence of neoplasia found in this case series. The clinical spectrum of heterotopic pancreas varies from asymptomatic to mild abdominal pain to severe peritonitis caused by gastrointestinal perforations. The occurrence of symptoms in patients aged ≤ 1 year, > 1–5 years, and > 5–18 years was 8/41 (19.51%), 6/32 (18.75%), and 8/15 (53.33%), respectively.

As depicted in Table 2, the heterotopic pancreas within Meckel’s diverticulum is typically located at the apex of the diverticular lumen, with a lesion size less than 1 cm in maximum diameter. Intestinal bleeding and intussusception were common symptoms. Heterotopic pancreas accompanying gastric mucosa heterotopia (GMH) (80.49%) was found in 33 patients, and those without GMH had a higher prevalence of heterotopic pancreas related symptoms (75%), p < 0.001.

Coexisting diseases, including Meckel’s diverticulum, gut malrotation, intestinal stenosis/atresia, intussusception, duplication cyst, gastrointestinal perforation, biliary atresia, congenital choledochal cyst, a peri-umbilical mass, mediastinal mass, and neuroblastoma, were diagnosed by radiography, upper gastrointestinal series (UGIs), ultrasonography, or endoscopic ultrasonography.

Management approaches included open surgery (Fig. 1), laparoscopic or laparoscopic-assisted mini-incision surgery for intra-abdominal lesions, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for gastric heterotopic pancreas (Figs. 2 and 3), and surgical removal of the umbilical lesions. Curative treatments included segmental bowel resection (n = 49), gastrointestinal wedge resection (n = 12), mass resection (n = 20), ESD (n = 6), and endoscopic biopsy (n = 1).

A 2-day-old boy with malrotation complicating midgut volvulus. (A) intraoperative findings showing a mass at the jejunal mesentery (yellow arrow) (B) gross pathologic appearance revealing an irregular mass along the mesenteric border (red arrow) compressing the adjacent jejunal wall (green arrows) (C) pathologic findings confirming heterotopic pancreas (Heinrich type I), including pancreatic acini (blue arrow), duct (white arrow), and islet cells (black arrow). (Hematoxylin–eosin stain, original magnification, 200 ×)

An 18-year-old boy with recurrent epigastric pain and non-bilious vomiting (A) gastroscopic view of a polypoid submucosal mass (gray arrow) with intact overlying mucosa located in the greater curvature of the stomach fundus (B) endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) showing a submucosal mass heterogeneous and hypoechoic (pink arrow), 2.5 cm × 2.0 cm in size, being suspicious for stromal tumor (C) ESD procedure, dissecting the mucosa to expose the submucosal mass (yellow arrow), removing the slight yellow-colored multilobulated massclip closure (green arrow) (E) ESD resected sample(F) pathological findings confirming heterotopic pancreas (Heinrich type I), including pancreatic acini (white arrow), duct (black arrow), and islet cells (blue arrow), (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification, 200 ×)

A 13-year-old boy with chronic epigastric pain. (A) an antral umbilicated submucosal nodule (white arrow) protruding into the gastric lumen under gastroscopy, suggestive of submucosal heterotopic pancreas (B) ESD technique (pink arrow) (C) defect after removal of the nodule (yellow arrow)clip closure post-ESD referring to Fig. 1D (D) ESD resected sample (E) pathological findings confirming heterotopic pancreas (Heinrich type II), including pancreatic acini (red arrow) and ducts (gray arrow). (Hematoxylin–eosin stain, original magnification, 200 ×). (F) appearance of endoscopic follow up 11 weeks after ESD (green arrow)

No postoperative hemorrhage, ESD perforations or bleeding, surgical site infection or organ/space infection, incision dehiscence, bowel anastomotic leak or stenosis, and adhesive small bowel obstruction related to the management of heterotopic pancreas occurred over six months to one year follow-up period.

Discussion

Heterotopic pancreas is defined as pancreatic tissue existing in an abnormal location and lacking any direct or vascular communication with the normal pancreas [6, 13, 14]. Its pathogenesis remains unclear.7 Based on the pathological classification, heterotopic pancreas is divided into three pathological types [11]. Type I consists of three components: acini, duct, and islet cellstype II is composed of acini and fewer ductsand type III consists of only pancreatic ducts. Some studies have revealed that gastrointestinal adenomyoma is a variant of type III heterotopic pancreas evidenced by the epithelial component resembling the pancreatic duct and the absence of acini formation [15]. For instance, Rhim et al. [16]. reported an 8-week-old infant who presented with obstruction due to gastric adenomyoma. In our study, two cases of adenomyoma were identified, including one concomitant with type I heterotopic pancreas. However, others consider adenomyomas to be myoepithelial hamartomas, an independent disorder with nonspecific symptoms [17].

The prevalence of heterotopic pancreas ranges from 0.6 to 13%, and with the widespread use of endoscopy screening, heterotopic pancreas is not a rare finding [5, 7, 13]. Clinical data analysis from our case series revealed that there was a slight predominance of males (1.84:1), with nearly half (46.59%) of the patients aged 1 year or younger.

Our case series confirmed previous findings that the heterotopic pancreas is commonly located at the apex of Meckel’s diverticulum, jejunum, umbilicus, ileum, and stomach [12, 18,19,20,21,22]. Heterotopic pancreatic tissues found within the Meckel’s diverticulum often accompany gastric mucosa heterotopia (80.49%), a finding seldom reported in the literature, with its pathogenesis remaining unclear [23, 24].

Regarding symptomatology, nearly 75% of the cases with heterotopic pancreas were incidentally diagnosed during other abdominal surgical procedures, consistent with previous reports [25]. The prevalence of symptoms related to heterotopic pancreas in patients aged 5 years and older was 53.33% compared to those under 5 years of age (19.18%). These results are consistent with the findings of Persano et al. [5]. Common symptoms included mechanical obstruction, bleeding, and umbilical discharge in the pediatric population [21]. Notably, heterotopic pancreas in the stomach may lead to clinical symptoms more often than in other sites. However, no evidence of neoplasia was observed in this study, although malignant transformation may complicate heterotopic pancreas in adults and adolescents [1, 5, 7].

The preoperative diagnosis of symptomatic heterotopic pancreas is challenging, and it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain, inflammation, obscure gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation, bowel or biliary obstruction, and malignant tumors [1, 19, 25]. Ginsburg et al. [26]. described mesenteric ectopic pancreatitis in an adolescent with acute abdominal pain and elevated serum lipase and amylase levels. Massive gastrointestinal bleeding caused by heterotopic pancreas is rare and is usually confirmed by endoscopy, CT enterography, laparoscopic exploration, exploratory laparotomy, intraoperative endoscopy, and even capsule endoscopy [20]. In our case series, twenty-five Meckel’s diverticulum cases presented with lower gastrointestinal bleeding, and only three were defined as heterotopic pancreas-associated bleeding. Heterotopic pancreas should be considered in the differential diagnosis among patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding after ruling out Meckel’s diverticulum with GMH [20]. It should also be considered in children with umbilical discharge [19]. Ultrasonography and fistulogram may help in making an accurate diagnosis.

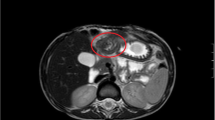

Heterotopic pancreas may present with a variety of symptoms requiring surgical intervention [4, 5, 21]. Gastric heterotopic pancreas can be misdiagnosed as other submucosal masses, such as stromal tumors. Imaging techniques like contrast CT and MRI can assist in making accurate diagnoses while EUS can show the origination and hypoechoic or mixed pattern of the heterotopic pancreas in the layers of the gastrointestinal wall [27,28,29].

Regarding management options, surgical removal of the heterotopic pancreas should be considered due to its potential complications, including inflammation, ulceration, gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation, bowel or biliary obstruction, and even malignant transformation with increasing age [8, 26]. In our present study, foci of the heterotopic pancreas were removed in all cases with ESD, laparoscopic, laparoscopic-assisted, or open surgical approach based on patients’ age, the lesion site and size, and co-existing diseases. Although over 86% of cases were treated with open surgery in this case series, minimal invasive approach should be considered as a treatment option in selected cases in the era of minimal access surgery [18, 29]. What’s more, EUS examination combined with extended biopsy or endoscopic SPOT® Tattooing may help decide the type of procedure in submucosal gastric heterotopic pancreas [30,31,32,33]. In recent years, the characteristic imaging features and precise preoperative diagnosis may help differentiate heterotopic pancreas from malignancies, thus avoiding unnecessary extensive surgical intervention [6].

Regarding the occurrence of intra-operative complications for excision of heterotopic pancreas, surgeons may face intra-operative technical challenges, such as performing complex and multiple procedures, intracorporeal suturing skills, conversion to open or laparoscopic repair, prolonged operative time and anesthesia time [34,35,36]. In our case series, one neonatal case had malrotation and midgut volvulus with incidental large mesenteric heterotopic pancreas, which was really decision-making dilemmas for surgeons. Excision of heterotopic pancreas with involved bowel segment and primary anastomosis was performed. Although the patient recovered uneventfully, longer operative time and anesthesia time, multiple procedures, and requirements of high experienced skills may increase intra-operative risks and postoperative complications in the newborn period. To ensure these patients in a stable condition and avoid potential intra- and postoperative complications, staged procedures [34] should be considered in both hemodynamically unstable and stable patients.

Regarding the postoperative complications of heterotopic pancreas, like other surgical procedures, infection (superficial incisional, deep incisional, and organ/space), incision dehiscence, bleeding, anastomotic leak/stenosis, or adhesive small bowel obstruction may occur in patients with heterotopic pancreas located in intestine or in mesentery involving bowel segment [36,37,38,39].

Our study has limitations, including its retrospective study design, somewhat small number of patients, and heterogeneity due to data collection from four different institutions over a longer period of time. A more diverse pool of cases may obtain a more representative sample and improve the generalizability of our experience.

Conclusions

Our multicenter retrospective study revealed that only 25% of the patients presented with symptoms. However, 75% of the cases had comorbidities, with the majority of the cases of Meckel’s diverticulum being accompanied by GMH. Surgical removal of the lesion is recommended due to its potential complications, highlighting the need for prospective multi-center studies to establish more rational treatment options, particularly in asymptomatic small babies or patients with severe coexisting diseases.

Data availability

Anonymus data can be provided upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Trifan A, Târcoveanu E, Danciu M et al (2012) Gastric heterotopic pancreas: an unusual case and review of the literature. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 21(2):209–212 (PMID: 22720312)

Lee MJ, Chang JH, Maeng IH et al (2012) Ectopic pancreas bleeding in the jejunum revealed by capsule endoscopy. Clin Endosc 45(3):194–197. https://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2012.45.3.194

Kung JW, Brown A, Kruskal JB et al (2010) Heterotopic pancreas: typical and atypical imaging findings. Clin Radiol 65(5):403–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2010.01.005

LeCompte MT, Mason B, Robbins KJ et al (2022) Clinical classification of symptomatic heterotopic pancreas of the stomach and duodenum: a case series and systematic literature review. World J Gastroenterol 28(14):1455–1478. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i14.1455

Persano G, Cantone N, Pani E et al (2019) Heterotopic pancreas in the gastrointestinal tract in children: a single-center experience and a review of the literature. Ital J Pediatr 45(1):142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-019-0738-3

Rezvani M, Menias C, Sandrasegaran K et al (2017) Heterotopic pancreas: histopathologic features, imaging findings, and complications. Radiographics 37(2):484–499. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2017160091

Cazacu IM, Luzuriaga Chavez AA, Nogueras Gonzalez GM et al (2019) Malignant transformation of ectopic pancreas. Dig Dis Sci 64(3):655–668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-018-5366-z

Serrano JS, Stauffer JA (2016) Ectopic pancreas in the wall of the small intestine. J Gastrointest Surg 20(7):1407–1408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-016-3104-4

Rao A, Wagner ES, Wieck MM et al (2020) An unusual lung mass of heterotopic pancreatic tissue in a neonate with an elevated immunoreactive Ttrypsinogen on newborn screen. Pediatric Dev Pathol 23(2):163–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/109352661987682

Seddon K, Stringer MD (2020) Gastric heterotopic pancreas in children: a prospective endoscopic study. J Pediatr Surg 55(10):2154–2158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.10.053

Heinrich H (1909) Ein Beitrag zur Histologie des sogen. akzessorischen Pankreas. Virchows Arch Pathol Anet 198:392–401

Kim DU, Lubner MG, Mellnick VM et al (2017) Heterotopic pancreatic rests: imaging features, complications, and unifying concepts. Abdom Radiol (NY) 42(1):216–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-016-0874-9

Kim DH, Kim JH, Han S et al (2022) Differentiation between small (< 4.5 cm) true subepithelial tumors and ectopic pancreas in the small bowel on computed tomography enterography. Eur Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-021-08252-7

Sharma S, Agarwal S, Nagendla MK et al (2016) Omental acinar cell carcinoma of pancreatic origin in a child: a clinicopathological rarity. Pediatr Surg Int 32(3):307–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-015-3850-5

Sakurai Y, Togasaki K, Nakamura Y et al (2024) Gastric type III heterotopic pancreas presenting as adenomyoma in the antrum of the stomach: a case report. Clin J Gastroenterol 17(1):34–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-023-01872-0

Rhim JH, Kim WS, Choi YH et al (2013) Radiological findings of gastric adenomyoma in a neonate presenting with gastric outlet obstruction. Pediatr Radiol 43(5):628–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-012-2521-0

Babál P, Zaviacic M, Danihel L (1998) Evidence that adenomyoma of the duodenum is ectopic pancreas. Histopathology 33(5):487–488. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.0491d.x

Vitiello GA, Cavnar MJ, Hajdu C et al (2017) Minimally invasive management of ectopic pancreas. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 27(3):277–282. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2016.0562

Kilius A, Samalavicius NE, Danys D et al (2015) Asymptomatic heterotopic pancreas in Meckel’s diverticulum: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 9:108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-015-0576-x

Juricic M, Djagbare DY, Carmassi M et al (2018) Heterotopic pancreas without Meckel’s diverticulum in children as unique cause of gastrointestinal bleeding: think about it! Surg Radiol Ana 40(8):963–965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-018-2042-0

Nakame K, Hamada R, Suzuhigashi M et al (2018) Rare case of ectopic pancreas presenting with persistent umbilical discharge. Pediatr Int 60(9):891–892. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.13637

Camoglio FS, Forestieri C, Zanatta C et al (2004) Complete pancreatic ectopia in a gastric duplication cyst: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg 14(1):60–62. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-815783

Murakami M, Tsutsumi Y (1999) Aberrant pancreatic tissue accompanied by heterotopic gastric mucosa in the gall-bladder. Pathol Int 49(6):580–582. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00905.x

Tanemura H, Uno S, Suzuki M et al (1987) Heterotopic gastric mucosa accompanied by aberrant pancreas in the duodenum. Am J Gastroenterol 82(7):685–688

Chou SJ, Chou YW, Jan HC et al (2006) Ectopic pancreas in the ampulla of Vater with obstructive jaundice. a case report and review of literature. Dig Surg. https://doi.org/10.1159/000096158

Ginsburg M, Ahmed O, Rana KA et al (2013) Ectopic pancreas presenting with pancreatitis and a mesenteric mass. J Pediatr Surg 48(1):e29-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.10.062

Dalal I, Cristelli R, Shahid H et al (2020) Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: ectopic pancreas presented as a large paragastric mass. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 35(6):920. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.15013

Jang KM, Kim SH, Park HJ et al (2013) Ectopic pancreas in upper gastrointestinal tract: MRI findings with emphasis on differentiation from submucosal tumor. Acta Radiol 54(10):1107–1116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0284185113491251

Matsumoto T, Tanaka N, Nagai M et al (2015) A case of gastric heterotopic pancreatitis resected by laparoscopic surgery. Int Surg 100(4):678–682. https://doi.org/10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00182.1

Kida M, Kawaguchi Y, Miyata E et al (2017) Endoscopic ultrasonography diagnosis of subepithelial lesions. Dig Endosc 29(4):431–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.12854

Liu X, Wu X, Tuo B et al (2021) Ectopic pancreas appearing as a giant gastric cyst mimicking gastric lymphangioma: a case report and a brief review. BMC Gastroenterol 21(1):151. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-01686-9

Liou YJ, Weng SC, Chang PC et al (2023) Localization and laparoscopic excision of gastric heterotopic pancreas in a child by endoscopic SPOT® Tattooing. Children (Basel) 10(2):201. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020201

MikovinyKajzrlikova I, Kuchar J, Vitek P et al (2024) Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic fluid collection in gastric heterotopic pancreas. a case report. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 168(1):92–96. https://doi.org/10.5507/bp.2022.043

Yu S, Liu J, Reid J, Clarke J et al (2024) Reoperation for post hepatectomy complications. ANZ J Surg 94(4):660–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.18803

Parelkar SV, Makhija DP, Sanghvi BV et al (2023) Initial experience with 3D laparoscopic choledochal cyst (CDC) excision and hepatico-duodenostomy (HD) in 21 children. Pediatr Surg Int 39(1):189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-023-05472-4

Maisat W, Yuki K (2023) Surgical site infection in pediatric spinal fusion surgery revisited: outcome and risk factors after preventive bundle implementation. Perioper Care Oper Room Manag 30:100308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcorm.2023.100308

Rafaqat W, Lagazzi E, Jehanzeb H et al (2024) Does practice make perfect? The impact of hospital and surgeon volume on complications after intra-abdominal procedures. Surgery 175(5):1312–1320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2024.01.011

Habti M, Miyata S, Côté J et al (2022) Bowel obstruction following pediatric abdominal cancer surgery. Pediatr Surg Int 38(7):1041–1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-022-05127-w

Miyake H, Seo S, Pierro A (2018) Laparoscopy or laparotomy for adhesive bowel obstruction in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int 34(2):177–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-017-4186-0

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families and appreciate all staff’s cooperation.

Funding

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaofeng Yang—project development, data collection, and manuscript writing. Chen Liu—data collection, data interpretation, and manuscript writing. Shuai Sun—data collection and manuscript writing. Chao Dong—project development and manuscript editing. Shanshan Zhao—data collection and manuscript editing. Zaitun M Bokhary—data collection and data interpretation. Na Liu—data collection and data interpretation. Jinghua Wu—project development and data interpretation. Guojian Ding—data collection and manuscript editing. Shisong Zhang—data collection and interpretation. Lei Geng—project development, data interpretation. Hongzhen Liu—project development, data collection and interpretation. Tingliang Fu—project development, data interpretation, manuscript editing. Xiangqian Gao—project development, data collection, data interpretation. Qiong Niu—project development, data interpretation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interests was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, X., Liu, C., Sun, S. et al. Clinical features and treatment of heterotopic pancreas in children: a multi-center retrospective study. Pediatr Surg Int 40, 141 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-024-05722-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-024-05722-z