Abstract

There is no consensus on the treatment of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), and practice seems to vary between centres. The main purpose of the present study was to survey current practice in Scandinavia. Thirteen paediatric surgical centres serving a population of about 22 million were invited, and all participated. One questionnaire was completed at each centre. The questionnaire evaluated management following prenatal diagnosis, intensive care strategies, operative treatment, and long-term follow-up. Survival data (1995–1998) were available from 12 of 13 centres. Following prenatal diagnosis of CDH, vaginal delivery and maternal steroids were used at eight and six centres, respectively. All centres used high-frequency oscillation ventilation (HFOV), nitric oxide (NO), and surfactant comparatively often. Five centres had extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) facilities, and four centres transferred ECMO candidates. The majority of centres (7/9) always tried HFOV before ECMO was instituted. Surgery was performed when the neonate was clinically stable (11/13) and when no signs of pulmonary hypertension were detected by echo-Doppler (6/13). The repair was performed by laparotomy at all centres and most commonly with nonabsorbable sutures (8/13). Thoracic drain was used routinely at seven centres. Long-term follow-up at a paediatric surgical centre was uncommon (3/13). Only three centres treated more than five CDH patients per year. Comparing survival in centres treating more than five with those treating five or fewer CDH patients per year, there was a tendency towards better survival in the higher-volume centres (72.4%) than in the centres with lower volume (58.7%), p =0.065.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is no consensus concerning perinatal treatment of patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH). Increasingly, CDH is diagnosed prenatally [1], and most authors advocate a planned delivery close to term at a tertiary centre [2]. However, centres vary in several important aspects of perinatal management [1, 3, 4].

During the last decade several new supportive CDH-treatment modalities have been introduced. The effects of these modalities has been sparsely documented [5]. The UK ECMO trial showed no significant survival benefit of ECMO in CDH patients [6, 7]. The advantage of ECMO in severe respiratory failure in newborn infants is less clear for CDH patients than for babies without CDH [8]. Randomised controlled trials (RCT) addressing the effect of nitric oxide (NO) in CDH patients reported no significant advantage of NO treatment [9, 10]. Two RCTs comparing early and delayed surgery failed to show any significant difference in survival between the two groups [11, 12], a finding that is in accordance with a recent systematic review [13]. Comparative studies have given important clues regarding ventilator settings; and gentle ventilation with permissive hypercapnea has been found to result in improved survival [1, 4, 14, 15]. A large study by the CDH Study Group revealed no consistency among centres in treatment strategies [16].

The lack of consensus on how to treat CDH patients prompted us to survey current practice in Scandinavia.

Material and methods

Thirteen paediatric surgical centres in the four Scandinavian countries were identified: two in Denmark, four in Finland, three in Norway, and four in Sweden. The population served by these centres is about 22 million, with approximately 280,000 births per year.

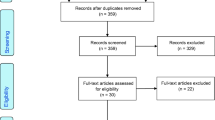

We conducted a cross-sectional survey with the centre as the unit of investigation. In order to increase the participation rate and according to the study protocol, the results of the participating centres are reported anonymously. One self-explanatory questionnaire in English was mailed to the head of each centre in October 1999. All centres participated, and all questionnaires were completed by March 2000. Twelve questionnaires were completed by paediatric surgeons and one by a paediatrician. The questionnaire included 28 items covering aspects of perinatal treatment following prenatal diagnosis, intensive care strategies, operative procedures, and long-term follow-up routines (Table 1). Centres that reported treating more than five CDH patients a year were defined as “high-volume centres”.

In a previous study, we retrospectively collected clinical data on 195 CDH patients (1995–1998) from 12 of the 13 centres participating in the present study [17]. Thus, available survival data predate the present questionnaire data. Survival to discharge is reported herein. In the present study, institutions treating more than five CDH patients a year were compared with those treating five or fewer. Risk stratification into three groups was performed as previously described by the CDH Study Group [18]. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS, Chicago, USA).

Results

The median estimated number of CDH patients was four per year (range 1–10) at each centre (Fig. 1). Three centres reported that they treat more than five CDH patients a year (“high-volume centres”).

Following prenatal diagnosis, a scheduled delivery close to term at a paediatric surgical centre was routine at all centres. Five centres planned delivery during week 38, three centres during week 39, and five centres during week 40. Six centres administered maternal steroids prenatally. Following prenatal diagnosis, eight centres (including two high-volume centres) preferred to deliver the baby vaginally, four preferred elective Cesarean section (including one high-volume centre), and one centre had no preference.

Prophylactic intubation of patients with CDH was favoured at four centres, whereas nine centres did not intubate until respiratory failure occurred. Eleven of 13 centres (including all three high-volume centres) preferred gentle ventilation with permissive hypercapnea. One centre applied a hyperventilation strategy, and one centre aimed at normal blood gases. Only five of 13 centres answered the question concerning positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). The median maximal PEEP in these centres was 4 cm H2O (range 1–5 cm H2O). Four centres responded to the question regarding peak inspiratory pressure (PIP). The median of the maximal PIP in these centres was 25 cm H2O (range 20–30 cm H2O).

Supportive treatment with surfactant, nitric oxide (NO), and high-frequency oscillation ventilation (HFOV) was commonly used (Table 2). Nine centres sometimes used ECMO. Five centres had ECMO facilities, and four centres had to transfer the ECMO candidate either by conventional transport or by using mobile ECMO if ECMO treatment was considered necessary [19]. In seven of nine centres HFOV was always tried before ECMO was started. The two remaining centres responded that HFOV frequently was tried before ECMO was started.

Delayed surgery, defined as that taking place after 24 h of age, was preferred at 12 centres and at two of three high-volume centres. A clinically stable patient was the most important criterion (12/13) for determining time of operation. Seven centres required that preoperative echo-Doppler demonstrated no signs of pulmonary hypertension. All centres performed repair by laparotomy. Nonabsorbable sutures were used at eight of 13 centres. Large defects were most commonly closed by a Gore-Tex patch (10/13). Routine appendectomy and Ladd’s procedure for malrotation were only performed at one and two centres, respectively.

Routine long-term follow-up at the perinatal centre was uncommon, occurring in only three centres.

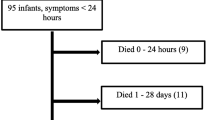

The overall survival rate (1995–1998) was 65% in 168 neonates with early symptoms (≤24 h) and 100% in 27 children with late symptoms [17]. The survival rate (neonates with early symptoms) in high-volume centres was 72.4% (55/76), compared with 58.7% (54/92) in non-high-volume centres (chi square =3.41, p =0.065). The data needed to calculate risk stratification groups were available for 152/168 neonates with early symptoms. Survival by hospital volume for those with predicted low, moderate, and high mortality risk is presented in Table 3.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that perinatal management of CDH patients differs widely across Scandinavia. The lack of harmonisation of CDH treatment in Scandinavia may be a consequence of lack of firm evidence about many aspects of perinatal CDH treatment. This is in accordance with the fact that most surgical procedures are not based on evidence from RCTs [20, 21].

The present study was not designed to compare outcome as a consequence of the reported management strategies. For this purpose, additional data are needed, and we intend to conduct such a study.

In accordance with the literature, all Scandinavian centres preferred that delivery after prenatal diagnosis take place close to term at a paediatric surgical centre [2, 22]. Eight of 13 centres preferred vaginal delivery, which is consistent with the fact that no study has demonstrated any benefit of routine Cesarean delivery of prenatally-diagnosed CDH patients [17, 23].

About half of the centres administered maternal steroids prenatally. None of these centres participated in any ongoing steroid trial. The relatively widespread use of prenatal maternal steroids following a prenatal diagnosis of CDH may be due to encouraging results in animal models [24], but the effect of prenatal maternal steroid treatment has only been reported in case series [25, 26].

The majority of centres (11/13) applied a gentle ventilation strategy with permissive hypercapnea. This strategy is highly beneficial according to large series, using historical comparisons, showing reduced frequency of barotrauma and superior survival after its implementation [1, 4, 15, 27].

The Scandinavian centres comparatively often used surfactant, NO, and HFOV, with infrequent use of ECMO. An intensive care strategy with infrequent use of ECMO has been shown to result in up to 80% survival [28]. Trials on NO treatment have shown no benefit in CDH patients as opposed to other causes of respiratory failure in neonates [9, 29]. No trials have been published evaluating the use of HFOV in CDH patients. Future trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of surfactant, NO, and HFOV in the management of CDH patients [5].

The UK ECMO trial did not show a significantly increased survival in CDH patients treated with ECMO compared with those treated without ECMO. However, only 35 CDH patients were included in that study [6]. Improved survival rates with ECMO have been reported in clinical series with historical controls [30, 31]. Moreover, a systematic review based on observational studies showed reduced preoperative mortality in the ECMO centres [32]. Stratified analysis of the CDH Registry data showed increased survival in the ECMO group among the most severely affected CDH patients [33]. Planned delivery of prenatally diagnosed CDH patients at an ECMO centre has been advocated [2]. We believe that the lack of firm evidence in favour of ECMO is the reason why this recommendation has not yet been implemented in all Scandinavian centres.

Most Scandinavian centres prefer delayed surgery, repair by laparotomy, and a low rate of appendectomy and malrotation procedures. This is in agreement with the data from the CDH Study Group [16].

The finding of varied clinical practice calls for prospective multicentre trials on management strategies. Treatment should be standardised in uncontroversial areas, and outcome data should be collected prospectively. Multicentre collaboration has been very helpful in some areas of paediatric surgical research [34], and a similar approach is encouraged for CDH research.

There is a reported long-term morbidity of up to 50% in CDH patients. Gastro-esophageal reflux, pulmonary problems, late bowel obstruction, nutritional problems, hearing problems, and skeletal malformations have been documented [5].Only three Scandinavian centres routinely arranged long-term follow-up of their CDH patients.

The annual number of CDH patients is very low at most Scandinavian centres, and the complexity of CDH treatment is increasing. Until now no studies on patient volume and outcome of CDH treatment have been published. In other paediatric surgical conditions needing highly specialised treatment, reduced mortality with increased patient load has been documented [35]. Our data suggest a tendency towards increased survival in centres treating more than five CDH patients per year, but the overall difference in survival did not reach significance ( p =0.065). For these reasons, centralisation of CDH management should be considered.

References

Kays DW, Langham MR, Jr., Ledbetter DJ, Talbert JL (1999) Detrimental effects of standard medical therapy in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Ann Surg 230:340–348

Finer NN, Tierney A, Etches PC, Peliowski A, Ainsworth W (1998) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: developing a protocolized approach. J Pediatr Surg 33:1331–1337

Azarow K, Messineo A, Pearl R, Filler R, Barker G, Bohn D (1997) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia—a tale of two cities: the Toronto experience. J Pediatr Surg 32:395–400

Wilson JM, Lund DP, Lillehei CW, Vacanti JP (1997) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia—a tale of two cities: the Boston experience. J Pediatr Surg 32:401–405

Muratore CS, Wilson JM (2000) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: where are we and where do we go from here? Semin Perinatol 24:418–428

UK Collaborative ECMO Trail Group (1996) UK collaborative randomised trial of neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Lancet 348:75–82

Bennett CC, Johnson A, Field DJ, Elbourne D (2001) UK collaborative randomised trial of neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: follow-up to age 4 years. Lancet 357:1094–1096

Elbourne D, Field D, Mugford M (2003) Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe respiratory failure in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, Issue 4: CD001340

Neonatal Inhaled Nitric Oxide Study Group (NINOS) (1997) Inhaled nitric oxide and hypoxic respiratory failure in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatrics 99:838–845

Jacobs P, Finer NN, Robertson CM, Etches P, Hall EM, Saunders LD (2000) A cost-effectiveness analysis of the application of nitric oxide versus oxygen gas for near-term newborns with respiratory failure: results from a Canadian randomized clinical trial. Crit Care Med 28:872–878

Nio M, Haase G, Kennaugh J, Bui K, Atkinson JB (1994) A prospective randomized trial of delayed versus immediate repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 29:618–621

de la Hunt MN, Madden N, Scott JE et al. (1996) Is delayed surgery really better for congenital diaphragmatic hernia? A prospective randomized clinical trial. J Pediatr Surg 31:1554–1556

Moyer V, Moya F, Tibboel R, Losty P, Nagaya M, Lally KP (2003) Late versus early surgical correction for congenital diaphragmatic hernia in newborn infants (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev, Issue 4: CD001695

Wung JT, Sahni R, Moffitt ST, Lipsitz E, Stolar CJ (1995) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: survival treated with very delayed surgery, spontaneous respiration, and no chest tube. J Pediatr Surg 30:406–409

Frenckner B, Ehren H, Granholm T, Linden V, Palmer K (1997) Improved results in patients who have congenital diaphragmatic hernia using preoperative stabilization, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and delayed surgery. J Pediatr Surg 32:1185–1189

Clark RH, Hardin WDJ, Hirschl RB et al. (1998) Current surgical management of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a report from the Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. J Pediatr Surg 33:1004–1009

Skari H, Bjornland K, Frenckner B et al. (2002) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Scandinavia from 1995 to 1998: predictors of mortality. J Pediatr Surg 37:1269–1275

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group (2001) Estimating disease severity of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in the first 5 minutes of life. J Pediatr Surg 36:141–145

Linden V, Palmer K, Reinhard J et al. (2001) Inter-hospital transportation of patients with severe acute respiratory failure on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation—national and international experience. Int Care Med 27:1643–1648

Kenny SE, Shankar KR, Rintala R, Lamont GL, Lloyd DA (1997) Evidence-based surgery: interventions in a regional paediatric surgical unit. Arch Dis Child 76:50–53

Baraldini V, Spitz L, Pierro A (1998) Evidence-based operations in paediatric surgery. Pediatr Surg Int 13:331–335

Stevens TP, Chess PR, McConnochie KM et al. (2002) Survival in early- and late-term infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatrics 110:590–596

Hentschel R, Wiethoff L, Hulskamp G et al. (1994) Manifestations and prognosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia [German]. Z Geburtsh Perinatol 198:81–87

Suen HC, Bloch KD, Donahoe PK (1994) Antenatal glucocorticoid corrects pulmonary immaturity in experimentally induced congenital diaphragmatic hernia in rats. Pediatr Res 35:523–529

Ford WD, Kirby CP, Wilkinson CS, Furness ME, Slater AJ (2002) Antenatal betamethasone and favourable outcomes in fetuses with ‘poor prognosis’ diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Surg Int 18:244–246

Taira Y, Miyazaki E, Ohshiro K, Yamataka T, Puri P (1998) Administration of antenatal glucocorticoids prevents pulmonary artery structural changes in nitrofen-induced congenital diaphragmatic hernia in rats. J Pediatr Surg 33:1052–1056

Downard CD, Jaksic T, Garza JJ et al. (2003) Analysis of an improved survival rate for congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 38:729–732

Somaschini M, Locatelli G, Salvoni L, Bellan C, Colombo A (1999) Impact of new treatments for respiratory failure on outcome of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Eur J Pediatr 158:780–784

Clark RH, Kueser TJ, Walker MW et al. (2000) Low-dose nitric oxide therapy for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Clinical Inhaled Nitric Oxide Research Group. N Engl J Med 342:469–474

Weber TR, Kountzman B, Dillon PA, Silen ML (1998) Improved survival in congenital diaphragmatic hernia with evolving therapeutic strategies. Arch Surg 133:498–502

Sreenan C, Etches P, Osiovich H (2001). The western Canadian experience with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: perinatal factors predictive of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and death. Pediatr Surg Int 17:196–200

Beresford MW, Shaw NJ (2000) Outcome of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Pulmonol 30:249–256

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group (1999) Does extracorporeal membrane oxygenation improve survival in neonates with congenital diaphragmatic hernia? J Pediatr Surg 34:720–724

Kumar R, Fitzgerald R, Breatnach F (1998) Conservative surgical management of bilateral Wilms tumor: results of the United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group. J Urol 160:1450–1453

McKiernan PJ, Baker AJ, Kelly DA (2000) The frequency and outcome of biliary atresia in the UK and Ireland. Lancet 355:25–29

Acknowledgements

Hans Skari was supported by the Norwegian Research Council and Dr. Alexander Malthe’s Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Contributors’ list

The study was designed by HS, KB, KW, and RE. Data collection was performed by all authors. Data entry and statistical analyses were performed by HS and RE. HS, KB, and RE organised the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Skari, H., Bjornland, K., Frenckner, B. et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a survey of practice in Scandinavia. Ped Surgery Int 20, 309–313 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-004-1186-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-004-1186-7