Abstract

Four recent reanalysis products ERA-Interim, NCEP-CFSR, MERRA-2 and JRA-55 are evaluated and compared to an older reanalysis JRA-25, to quantify their confidence in representing Cut-off lows (COLs) in the Southern Hemisphere. The climatology of COLs based on the minima of 300-hPa vorticity (\(\xi_{300}\)) and 300-hPa geopotential (\(Z_{300}\)) provides different perspectives of COLs and contributes to the understanding of the discrepancies observed in the literature regarding their numbers and seasonality. The COLs compare better among the newest reanalyses than compared to the older reanalysis JRA-25. The difference in number between the latest reanalyses are generally small for both \(\xi_{300}\) and, with more COLs identified in \(\xi_{300}\) than in \(Z_{300}\) for all reanalyses. The spatial differences observed between the newest reanalyses are mainly due to differences in the track lengths, which is larger in ERA-Interim and JRA-55 than in NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2, resulting in disparities in the track density. This is likely due to the difference in the assimilation data system used in each reanalysis product. The largest differences in intensities occur in the \(\xi_{300}\), because this field is very sensitive to the reanalysis resolution. The mean separation distance of the COLs that match between the latest reanalyses are generally small, while the older JRA-25 has a broader distribution and larger number of matches with relatively large distances, indicating larger uncertainties in location of COLs. The results show significant improvements for the most recent reanalyses compared to the older JRA-25 reanalysis, indicating a progress in representing the COL properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the past years, several climatologies of Cut-off lows (COLs) have been obtained for different parts of the world, such as in the Northern Hemisphere (NH) (Price and Vaughan 1992; Kentarchos and Davis 1998; Nieto et al. 2005; Porcù et al. 2007) and more recently in the Southern Hemisphere (SH) (Fuenzalida et al. 2005; Reboita et al. 2010; Ndarana and Waugh 2010; Favre et al. 2012, Pinheiro et al. 2017, hereafter P17). In particular, the focus of attention has been on revealing the climatological aspects of COLs, such as their spatial distribution, seasonality, intensity, mean lifetime, and genesis and lysis statistics. The use of objective schemes to identify COLs allows the analysis to be reproduced fairly consistently over time, avoiding subjective decisions as usually happens in manual methods.

The earliest objective climatology of SH COLs was carried out by Fuenzalida et al. (2005) based on the Laplacian of 500-hPa geopotential of National Centers for Environmental Prediction–National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCEP-NCAR) reanalysis data (Kalnay et al. 1996). Later, other studies have investigated the synoptic and climatological features of COLs in the SH, focusing on particular regions (Campetella and Possia 2007; Singleton and Reason 2007) or the entire hemisphere (Ndarana and Waugh 2010; Reboita et al. 2010; Favre et al. 2012; Ndarana and Waugh 2010; P17). These studies are based on relatively old reanalysis datasets obtained using earlier forms of data assimilation and at relatively low spatial resolution, such as the NCEP-NCAR, the 40-year Reanalysis European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecast (ECMWF) (hereafter ERA-40), and the NCEP Department of Energy (NCEP-DOE). The exception is the study of P17 that used a more modern reanalysis product, the ECMWF—Interim reanalysis (hereafter ERA-Interim).

Reanalysis datasets are a valuable homogeneous source of atmospheric data, in particular for the SH where the large oceanic areas and the sparse network of observations make the assimilated data dominated by satellite observations. Evaluating the skill of reanalyses is important since they are widely used for studying synoptic systems such as COLs. Moreover, reanalysis datasets have been widely used to evaluate the ability of climate models to reproduce the observed climate in the SH, as demonstrated in several studies (Fyfe 2003; Marshall et al. 2004; Mitas and Clement 2006; Harvey et al. 2012; Jones and Carvalho 2013).

In Reboita et al. (2010), a comparison of SH COLs identified at three pressure levels (200, 300, and 500 hPa) was performed for a 21-year period (1979–1999) using the ERA-40 and the NCEP-NCAR reanalysis. These authors found substantial differences between the reanalyses with respect to number and seasonality. In general, the number of COLs identified in the ERA-40 is larger than that identified in the NCEP-NCAR. Nieto et al. (2008) used the same reanalysis datasets to obtain the spatial distribution of the NH COLs for a 45-year period (1958–2002) and found an improvement in the agreement between the ERA-40 and the NCEP-NCAR reanalysis in comparison to the results found by Reboita et al. (2010). This indicates uncertainties in the austral COLs possibly due to the lack of observations in the SH compared to the NH, in particular before the advent of satellites. Moreover, the differences between studies are also due to the different methods for COL identification, which is related to how a COL is defined (Pinheiro et al. 2019).

The discrepancies between ERA-40 and NCEP-NCAR reanalysis observed in previous studies may occur as a result of different causes, such as the problems with the components of the hydrological cycle associated with the humidity analysis in ERA-40, as discussed in Bengtsson et al. (2004). Additionally there is a problem with the Australian surface pressure bogus data called PAOBS for the years 1979–1992 (http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/wesley/paobs/ek.letter.html), that is used for both older reanalysis of NCEP and ECMWF, although this problem affects only some variables of the reanalysis mainly south of about 40° S–60° S.

Recent atmospheric reanalyses, produced with state-of-the-art atmospheric models and advanced data assimilation systems, have improved markedly over earlier ones with known issues being improved, making the newer reanalyses more reliable for representing the properties of synoptic systems. In a study of extratropical cyclones, Hodges et al. (2011) show that the improvement of using more recent reanalysis is more evident in the SH. The main benefits of using modern reanalyses include the increased spatial resolution, more complete observational network, more realistic representation of dynamics, and improved data assimilation schemes and variational bias correction of satellite radiances.

In the recent study of P17, a seasonal analysis of the SH COLs was performed using the ERA-Interim reanalysis. A wide range of statistics are used to explore the main COL characteristics using an objective scheme to identify and track COLs based on the 300-hPa relative vorticity minima, and three restrictive criteria for the presence of a cold-core, stratospheric air intrusion, and cut-off cyclonic circulation. The results indicate that the differences in seasonality observed between previous studies are due to differences in the reanalyses as well as the different approaches used to identify COLs.

For the present paper, a similar but simpler method than that presented in P17 is used for the COL detection, which has no temperature and potential temperature criteria. The advantage of using the simpler method is that a larger number of systems are identified in comparison to the method based on multiple criteria, allowing more tracks to be used in the analysis. In addition, the use of a simpler scheme reduces the complexity of the computations which allows an easier detection of COLs by simply imposing on the detection system a cyclonic circulation appearance regardless of the physical and dynamical characteristics (Pinheiro et al. 2019). The results from P17 will be considered as the basis for the comparison for the 300-hPa COLs in this paper but with the analysis extended to the 300-hPa geopotential COLs in order to present two different perspectives.

So far, Reboita et al. (2010) is the only study that has evaluated two different reanalyses in representing the COLs in the SH. Given the importance of continuing to assess the reanalyses, the goal of this study is to understand the uncertainties in the reanalysis datasets by comparing different reanalyses in terms of SH COL properties such as numbers, spatial distribution, intensity and variability. Thus, we intend to determine the reanalyses deficiencies and the impact of the improvement over the earlier reanalyses. The paper continues in Sect. 2 with a description of each reanalysis system and the methodology used to identify COLs. Section 3 presents results for the temporal and spatial distributions and the intensities of the COLs as well as a direct matching of COLs between different reanalyses to determine which COLs are common between the reanalyses. Section 4 summarises the results and presents the conclusions.

2 Data and methodology

2.1 Reanalysis datasets

The five reanalyses investigated in this study for COLs are: the ERA-Interim (Dee et al. 2011), the NCEP Coupled Forecast System Reanalysis (NCEP-CFSR) (Saha et al. 2014), the second National Aeronautics and Space Administration Modern Era Retrospective Reanalysis for Research and Applications (NASA MERRA-2, hereafter MERRA-2) (Bosilovich et al. 2016) and the two reanalyses produced by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) which are the Japanese 25- and 55-year Reanalysis Project (JRA-25 and JRA-55) (Onogi et al. 2007; Ebita et al. 2011; Kobayashi et al. 2015). Four of the datasets represent the new generation of reanalyses (ERA-Interim, NCEP-CFSR, MERRA-2 and JRA-55), which are more recent than the reanalyses used in previous studies of COLs in the SH (e.g. Favre et al. 2012; Ndarana and Waugh 2010; Reboita et al. 2010), except for P17 who used the ERA-Interim reanalysis. JRA-25 is expected to provide the largest contrast between reanalyses since JRA-25 is the oldest and the lowest resolution data set used in this study. A key difference between the reanalyses is that the NCEP-CFSR is the only reanalysis used in this study which is fully coupled and which assimilates ocean observations as well as atmospheric observations, while the other reanalyses are atmosphere only systems that use prescribed boundary conditions of SSTs and sea ice. A summary of the configuration differences between the reanalyses is given in Table 1.

The reanalyses used in this study cover the modern satellite period after 1979, though JRA55 begins in 1958. The results of the comparison between the five reanalyses are obtained for the 30-year period 1980–2009. The reason for this period is because some reanalyses do not cover recent years, such as the NCEP-CFSR which is not available beyond 2010, though this could be extended with the operational analyses but there are some model changes. The dataset that provides the longest time range data, the Twentieth Century Reanalysis Project (Compo et al. 2011), would not be appropriate for this purpose since only surface observations are assimilated which are sparse in the SH, although this type of reanalysis has been very useful to study low-frequency variability of specific phenomena, particularly that associated with low-tropospheric fields (Cerrone et al. 2017). The fields used for the COL identification and tracking are horizontal winds, relative vorticity and geopotential at 300 hPa.

2.2 Cut-off low identification and matching approach methods

A feature-tracking algorithm is applied to identify and track the upper-level COLs by using the simplest scheme described in Pinheiro et al. (2019) where the identification process is based only on winds as additional fields. The COL detection is performed on the relative minima in the 6-hourly 300-hPa vorticity (Z300) and 300-hPa geopotential (ξ300) in order to provide two different perspectives.

Before the tracking is performed, the large-scale background is removed as performed in recent studies on COLs (P17; Pinheiro et al. 2019) and discussed in Hoskins and Hodges (2002). Vorticity is spectrally truncated at T42 to smooth this very noisy field, whilst the T63 resolution is used for the geopotential field as it is a generally smoother field. This procedure reduces the resolution of each reanalysis to the same spatial scale for each field, which allows a fair comparison between reanalyses with different resolutions. The main problem in using the geopotential at 300 hPa is that the gradient is normally weak at low latitudes, therefore the zonal mean is removed from the geopotential data at each time step and for each latitude to emphasize the synoptic features. This allows the “weak” extremes to be more easily identified than in the raw geopotential, resulting in the detection of a larger number of COLs compared to the method using the unfiltered geopotential field.

Initially all systems at the 300 hPa are identified and tracked as features lower than − 1.0 × 10−5 s−1 for \(\xi_{300}\) and − 50 geopotential meters (gpm) for \({\text{Z}}_{300}\). Feature points are initially linked together using the nearest neighbour approach and then refined by the optimization of a cost function (Hodges 1999). A post-tracking filter is employed to guarantee that the cyclonic features are completely detached from the westerlies. This is done by referencing the horizontal wind components (u, v) to the tracks at a fixed radial distance of 5° (geodesic distance) from the COL centre in four directions relative to the centre, which are 0° (u > 0), 90° (v < 0), 180° (u < 0), and 270° (v > 0) relative to North. The COL is defined when these conditions are fulfilled for at least four consecutive points along the track. As the focus of this study is on subtropical COLs, only the tracks that move northward and reach at least 40° S or have their genesis north of 40° S are included. The more northern boundary is fixed at 15° S, i.e. tracks that are north of this latitude are excluded to reject tropical cyclonic vortices (Kousky and Gan 1981).

To assess in more detail how COLs in different reanalyses compare to each other, the identical COLs are identified using a matching approach (Hodges et al. 2011). The identically same COLs are defined as the tracks with mean separation distance less than 4° (geodesic) that overlap in time by at least 50% of the track points. A wide range of spatial statistics for the activity of COLs was explored in P17 but in the present study only the track density is used. The track density is determined using spherical kernel estimators (Hodges 1996). The discussion of the spatial statistics will focus on the austral autumn (MAM) and winter (JJA) which have respectively the largest frequency and intensities of COLs in the SH (P17).

3 Results

This section presents results comparing the five different reanalysis for the SH COLs based on the and Z300. Before presenting the results comparing different reanalyses, the climatology of COLs using the ERA-Interim is shown in order to provide a general view of the spatial distribution of COLs. The ERA-Interim reanalysis was chosen arbitrarily, but this does not affect any of the interpretations made for further results.

3.1 Climatology

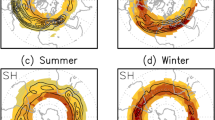

The COL track densities based on the and for austral autumn and winter are shown in Fig. 1. This climatology differs somewhat from the previous study using the same algorithm (P17), but with more complex criteria based on temperature and potential vorticity. The two climatologies of COLs differ mainly in terms of numbers and intensity of the COLs detected. The sensitivity of identifying COLs using multiple criteria is examined in a recent study by Pinheiro et al. (2019).

Southern Hemisphere COL track density for the austral a, b autumn (MAM) and c, d winter (JJA), identified by 300-hPa vorticity (a, c) and filtered geopotential (b, d) for the period from 1980 to 2009. Unit is number per unit area per season, the unit area is equivalent to a 5º spherical cap (~ 106 km2)

The track density with (Fig. 1b, d) indicates a similar spatial distribution between autumn and winter, the largest values are found from southeast Australia to the western Pacific, southeast Pacific near the west coast of Chile, and southern Africa and surroundings, which is agreement with earlier studies (Keable et al. 2002; Fuenzalida et al. 2005; Reboita et al. 2010; Ndarana and Waugh 2010). The large frequencies of COLs in Australia and neighborhoods coincide with preferred areas of genesis and lysis (P17) where the COLs are often associated with the occurrence of blocking (Trenberth and Mo 1985). For the vorticity perspective, a remarkable seasonal variation between autumn and winter is observed. The track density shows the maximum values around the continental areas in winter, but extending into oceanic regions in autumn. Note that the largest differences between \(Z_{300}\) and \(\xi_{300}\) are seen in autumn mainly in the central Indian Ocean where the density values in \(\xi_{300}\) are much larger than in \(Z_{300}\). In autumn when the COL mean intensity is not as strong as in winter (see Figs. 5 and 6 of P17) using the \(\xi_{300}\) seems to be more able to capture the COLs compared to using the \(Z_{300}\).

The differences observed between the \(Z_{300}\) and \(\xi_{300}\) COLs is probably related to their different spatial scales. In general, methods using fields that emphasise the smaller synoptic scales (e.g. vorticity) tend to identify longer tracks than methods using larger-scale fields such as geopotential (Hodges et al. 2003; Grieger et al. 2018). This affects the life cycle of the detected system, resulting in differences in numbers particularly for the counts of short-lived systems (Rudeva et al. 2014). For our study, the choice of the tracking parameter has important implications for the track density estimation since this statistic is sensitive to the track length. Hence, longer tracks contribute to higher track densities, while shorter tracks contribute to smaller densities. This may be the reason for the track density gaps in the ocean areas observed in the compared to the in Fig. 1. A somewhat similar distribution of the COLs has been shown in previous studies that use the geopotential for the tracking (e.g. Fuenzalida et al. 2005; Reboita et al. 2010).

3.2 Differences in numbers

The number of COLs based on and for each reanalysis is summarised in Table 2. For the annual mean, the largest number of systems is found in JRA-55 for (518.1) and in ERA-Interim for (407.0), while the smallest number of systems is found in JRA-25 for both (485.1) and (372.4). The reason why the ERA-Interim and JRA-55 have more tracks than NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2 is unclear, even though the former reanalyses do not have the highest resolutions. One hypothesis for the larger number of COLs in ERA-Interim and JRA-55 is that these reanalyses are produced with the same type of model and data assimilation system (4D-Var), whereas the NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2 reanalyses both use the the 3D-Var GSI data assimilation.

The numbers of COLs identified in the reanalyses for each season compare well in most reanalyses. If considering only the latest reanalyses the results are very impressive since the differences in numbers are generally less than three tracks per season (~ 3% of total number) for both and. The exception is the comparisons between JRA-55 and MERRA-2 in winter, in which the differences in values reach 5.9 systems in. These values are comparable to numbers found for extratropical cyclones in the NH and SH (Hodges et al. 2011). In contrast, the differences in numbers of COLs between JRA-25 and the newest reanalyses are much larger and the average difference is about 7-8 COLs per season, although the difference reaches 13.4 COLs for the JRA-25 comparison with JRA-55 of \(\xi_{300}\) COLs in winter.

It is noticeable that the number of COLs is greater than the number of COLs for all reanalyses due to the difference in scale as discussed in Hoskins and Hodges (2002), although the post-tracking filtering reduces the differences between the two fields since very small-scale systems will be excluded. Despite this, \(\xi_{300}\) COLs are more frequent than COLs even if the highest resolution reanalysis is contrasted with the lowest resolution reanalysis, that is, the NCEP-CFSR and JRA-25 reanalyses respectively. The only exception occurs in winter when the number of COLs for NCEP-CFSR (84.9 COLs) is slightly higher than the number of COLs for JRA-25 (84.8 events). The large differences between the COLs identified in vorticity and geopotential become even more obvious when the tracks are contrasted through a spatial–temporal matching approach, as described in Sect. 2.2. For example, the percentage of the \(\xi_{300}\) COLs that matches against the COLs correspond to 61.7% (78.3%) of the total number of (\(Z_{300}\)) COLs in the ERA-Interim. These numbers are comparable to those obtained in other modern reanalysis such as NCEP-CFSR (60.1%/76.6%), MERRA-2 (60.7%/76.2%) and JRA-55 (59.6%/77.5%), but a reduced number of matches is found regarding to the JRA-25 comparison, corresponding to 57.8% and 75.3% of the total number of and \(Z_{300}\) COLs, respectively. However, these numbers are dependent on the threshold chosen for detecting COLs which in turn may be somewhat arbitrary and difficult to define due to the nature of individual systems.

3.3 Differences and similarities in spatial distribution

To investigate the differences in the spatial distribution of COLs, the differences in track density between the reanalysis datasets are shown in Figs. 2 and 3, using ERA-Interim as a reference. The periods analysed here are the austral autumn (MAM) and winter (JJA), which have the most frequent and intense COLs respectively (P17). The frequency of COLs in summer is comparable to the frequency observed in autumn, particularly for the, but summer COLs are much weaker than the systems in other seasons.

Differences of track density for the \(\xi_{300}\) Cut-off lows in the Southern Hemisphere, between ERA-Interim and NCEP-CFSR (top), ERA-Interim and MERRA-2 (middle), and ERA-Interim and JRA-55 (bottom) for the austral autumn (left panel) and winter (right panel). The analysis is performed for the 30-year period (1980–2009). Units is number per unit area, the unit area is equivalent to a 5º spherical cap (≅ 106 km2)

As Fig. 2, but for the differences ERA-Interim—JRA-25 (top), and NCEP-CFSR—MERRA-2 (bottom)

For the comparison between ERA-Interim and NCEP-CFSR (i.e. ERAI—NCEP-CFSR, Fig. 2a, b), the track density shows there are relatively small differences, typically less than 3–5 per season per unit area. Positive values indicate that the track density has larger values in ERA-Interim than in NCEP-CFSR. The largest values occur in autumn for regions where the COL activity is high (see Fig. 1), such as in the western Pacific and southern Africa where the values reach 3–5 per season per unit area in autumn and winter. For the ERA-Interim comparison with MERRA-2 (Fig. 2c, d), the differences are similar to those seen in the NCEP-CFSR comparison with the largest differences in regions of high values of track density. Comparing ERA-Interim with JRA-55 (Fig. 2e, f), it is noticeable that in general the differences are much smaller than those observed in NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2. Most regions present values ranging between − 1 and 1 in both autumn and winter. The largest differences are observed south of Madagascar in autumn and through the western and eastern Pacific in winter, but the values do not exceed 1–3 per season per unit area. The largest differences in track density are observed for the JRA-25 (Fig. 3a, b), with in many areas there are values ranging from 3 to 5 between 25° S and 35° S, and reaching values up to 5–7 on the southwest coast of Africa and near Madagascar in autumn.

For another perspective, the track density between NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2 is compared (Fig. 3c, d). Results show that there is an improvement in the agreement compared to ERA-Interim. In general the differences between NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2 are close to zero in the main COL region for both autumn and winter, similarly to the comparison between ERA-Interim and JRA-55. These results suggest that the similarities between ERA-Interim and JRA-55 as well as between NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2 are likely related to the way the data are assimilated in each reanalysis, since the best performances were achieved by comparing reanalyses produced with similar assimilation systems. It is worthwhile mentioning that the differences in numbers of COLs between the more recent reanalyses are relatively small as shown in Table 2. The differences in the track density are mainly due to the differences in the track length, which is larger in ERA-Interim and JRA-55 than in NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2 (figure not shown). The longer tracks lead to an increase in overlapping tracks and consequently an increase in the track density. Similar results were found in the track density based on geopotential (figure not shown).

3.4 Monthly distribution

Figure 4 shows the monthly distribution of the 300-hPa SH COLs based on the and for each reanalysis. This shows that there is a well-defined cycle with the peak in March and the minimum in June, July or August, with small differences in distribution between reanalyses. For most reanalyses the minimum occurs in June for and in August for. The more pronounced seasonal cycle in rather than in may be as a consequence of a higher number of small-scale weak \(\xi_{300}\) systems in summer, as observed in all reanalyses. The largest difference occurs in the JRA-25 distribution, in particular during winter and spring months when the numbers of COLs are much less than those observed in the newest reanalyses. However, if considering only the four newest reanalyses, the differences are not significant, which is consistent with the results found through comparative studies for extratropical cyclones (Hodges et al. 2011) and tropical cyclones (Hodges et al. 2017). It is then plausible that the newer reanalyses have improved over the older ones in their representation of cyclones and COLs in both hemispheres. The large standard deviation found in January and February for and September for (figure not shown) reveals a significant interannual variability, which will be examined in detail in the next section.

Monthly distribution of the and Cut-off Low number for the reanalysis ERA-Interim (solid line), NCEP-CFSR (dotted line), MERRA-2 (dashed line), JRA-55 (dashed-dotted line), and JRA-25 (dashed-double-dotted line). Vorticity in black lines and geopotential in red lines. Analysis is performed for the latitudinal range 15º S–50º S for the 30-year period (1980–2009)

3.5 Interannual variability

The interannual variability of the and COLs in terms of frequency is shown in Fig. 5. During the 30-year period 1980–2009, there seems to be no obvious trend in the number of and COLs represented in each reanalyses, but there is clearly a considerable variation over this period, with noticeable peaks and troughs. The highest standard deviation of the COL number is found in NCEP-CFSR for both (26.6) and (24.7), whereas ERA-Interim has the lowest standard deviation (21.0, 19.8). It is not surprising that the largest differences between reanalyses occur throughout the first half of period, when the uncertainties are larger than the more recent years due to the quality and available observations that are assimilated. In contrast, the period that started from the start of the 21st century is particularly marked by reducing differences between the reanalyses, performing better with respect to the COL variability.

Interannual distribution of the Cut-off Low number based on and for the reanalysis ERA-Interim (solid line), NCEP-CFSR (dotted line), MERRA-2 (dashed line), JRA-55 (dashed-dotted line), and JRA-25 (dashed-double-dotted line). Vorticity in black lines and geopotential in red lines. The analysis is performed for the latitudinal range 15º S–50º S for the 30-year period (1980–2009)

Interestingly, there are a number of studies that have reported a positive trend of COL activity in terms of interannual and interdecadal scales for both the southern (Fuenzalida et al. 2005; Pezza et al. 2007; Piva et al. 2008; Favre et al. 2012) and northern hemispheres (Wang et al. 2006; Nieto et al. 2007). Fuenzalida et a. (2005), using the NCEP-NCAR reanalysis for a 31 year-period (1969–1999), who found a positive trend for the number of COLs in the African and South American sectors, in particular from 1999, but a decrease in number occurred for COLs in Australia. For the same regions, similar results have been found by Favre et al. (2012) for the period 1979–2008 using the NCEP DOE reanalysis, also known as NCEP 2 reanalysis (Kanamitsu et al. 2002), which is based on the same system as used for NCEP-NCAR, who suggested the positive trend may be as a result of the temperature and pressure rising in mid-latitudes as reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessment (IPCC 2007). Hence more highs and cut-off low pressure systems associated with blocking patterns are generated, as suggested by Favre et al. (2012). The findings of the present work do not show an obvious trend, and even slight negative trends occur in the NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2 reanalyses for the tracks (figure not shown). No noticeable trend is apparent for all five reanalyses for both and tracks even though a simpler method is used (without a filter to detect a cut-off circulation), where about 70% of the detected tracks were observed as open troughs in the geopotential maps by a visual inspection (figure not shown). Also, our study did not analyse the interannual variability in terms of the COL intensity which may be interesting to examine in future work.

It is also important to remark that some discrepancies observed between studies are related to the different types of weather systems and regions chosen in addition to the dataset used for the analysis, as pointed out by Wang et al. (2006). For the large number of studies that have found a positive trend, it is reasonable to consider this aspect may be related to the increase in quality of available observations and how they are assimilated (Simmonds and Keay 2000). The studies that found a positive trend, as commented before, used relatively old reanalyses with low resolution in which the reanalyses have some problems in observations in the SH, as discussed before. Therefore, the use of the more recent reanalyses, which have more modern atmospheric models and assimilation systems, and with known problems found in previous versions corrected, provides much more confidence in the analysis of weather systems in the SH.

An interesting aspect of the COL distribution is the abrupt decrease in occurrence in 2002, represented for all the reanalysis in both and. The reduction in the number of COLs is well defined in spring (figure not shown) and may be associated with the anomalous event of a Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW) in 2002, as discussed in many studies (e.g. Varotsos 2004; Charlton et al. 2005; Kruger et al. 2005; Newman and Nash 2005; Orsolini and Randall 2005; Thompson et al. 2005). A SSW is characterized by an abrupt disruption of the westerly winds associated with the winter stratospheric polar vortex. For the NH, numerous studies have shown evidence of the stratosphere-troposphere coupling (e.g. Andrews et al. 1987; Limpasuvan et al. 2004), suggesting the deceleration of the stratospheric polar vortex that impacts the tropospheric circulation. In particular, a SSW event is often accompanied by a shift of the jet stream and storms tracks equatorward (Baldwin and Dunkerton 2001). However, SSW events are very rare in the SH due to the smaller planetary wave amplitude (Van Loon et al. 1973). The exception is the unique and remarkable case of September 2002, the only SSW event detected in the SH since the satellite observations began in 1979 (Butler et al. 2017). Despite the evidence of the importance of the SSW in positioning the main mid-latitude storms tracks, it is unclear what the influence of SSWs are in the subtropics. A hypothesis for the decrease in number of COLs is that during the extraordinary event of SSW in 2002 the equatorward displacement of the jet stream would strengthen the lower mid-latitude zonal flow, which is not favorable for COL formation.

Although the main focus of this study is not on the low-frequency variability, some large-scale modes have been investigated. The possible association between the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the frequency of COLs is examined. This found that the annual mean Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) is temporally correlated with the annual number of and COLs in each reanalysis in respect of El Niño and La Niña events. Table 3 shows the correlation coefficients between the SOI and and COL numbers. The two-tailed student’s t test is used to test the significance of the correlation coefficients. The highest correlations are found for JRA-55 and JRA-25 for the COLs with values of 0.58 and 0.45, respectively, which are statistically significant at a 99% confidence level. In contrast, the correlation coefficients for the COLs identified by the NCEP-CFSR are low compared with those in other reanalyses (about 0.09), indicating these systems are less correlated with the SOI. The relatively weak correlation in NCEP-CFSR for the is related with particular years (1987, 1989, 1990, and 1997) in which the correlation was negative, while the other reanalyses presented very high correlation values. A common aspect between the reanalyses is the positive correlation coefficients for both and COLs, indicating the increase in number of systems may be related to the La Niña episodes, which corroborates the findings of Singleton and Reason (2007) for the southern Africa region and Favre et al. (2012) for the entire hemisphere. During the cold phase of ENSO, negative anomalies of SST near the equator decrease the meridional pressure gradient between lower and mid-latitudes, weakening the westerlies associated with the subtropical jet which is found to be favourable for COL genesis. Other indices used to characterize the SST anomalies in different sectors of the tropical Pacific as well as the correlation for seasonal frequencies could be interesting to be considered for further work.

There are other patterns of large-scale atmospheric variability that might affect COLs such as the Southern Annual Mode (SAM) or Antarctic Oscillation, the Pacific South American mode (PSA), and the Semi-annual Oscillation (SAO). For the SAO, in particular, a few studies have found a half-yearly cycle of COLs and a positive correlation with the COL frequency (Singleton and Reason 2007; Ndarana and Waugh 2010; Favre et al. 2012). However, the results shown here do not show a semi-annual cycle of COLs, nor does the method that uses a multiple step scheme to identify COLs (P17).

3.6 Intensity distributions

The maximum intensity distributions of the and COLs referenced to the full resolution for and, are shown in Fig. 6 as a probability density distribution. These values are computed for all tracks identified in each reanalysis over an area averaged within a 5° (geodesic) radius. If the direct search for absolute minima is performed within the same area the results are very similar to the distribution produced using an area average. The distribution of intensities for the COLs (Fig. 6a) shows that there is a broad range of values and significant differences between the reanalyses. NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2 have stronger COLs (higher-intensity tails) than the other reanalysis, and JRA-25 has the weakest extremes. It is plausible that the higher resolution reanalyses help to produce the most intense systems, although a larger number of COLs is not always found (see Table 2). There are other reasons, in addition to the resolution, that contribute to the differences in the intensities of \(\xi_{300}\) COLs between the reanalyses such as the data assimilation system and forecast model, which may explain the differences in the intensity distributions found between reanalyses with similar resolutions such as JRA-55 and JRA-25. For the intensities based on the (Fig. 6b), the distribution shows much smaller differences between the reanalyses than that shown for \(\xi_{300}\). Again, MERRA-2 and NCEP-CFSR have the deeper COLs in comparison to the other reanalyses, whereas the JRA-25 consistently underestimates the intensities compared to the higher resolution datasets. Smaller differences are expected between the geopotential distributions since the geopotential tends to focus on the large-scale features, which are less influenced by the reanalysis resolution.

Probability density function of the intensity for the a, b Cut-off lows obtained from the reanalyses ERA-Interim (solid line), NCEP-CFSR (dotted line), MERRA-2 (dashed line), JRA-55 (dashed-dotted line), and JRA-25 (dashed-double-dotted line). Units is 10−5 s−1 for vorticity and gpm for geopotential, both scaled by − 1. Analysis is perfomed for the latitudinal range 15º S–50º S for the 30-year period (1980–2009)

3.7 Track matching

A more detailed comparison of COLs between the reanalyses is performed by matching the identically same COLs. The matches are determined as described in Sect. 2.2. The number of matches for each pair of reanalysis for both the and tracks are shown in Table 4. Percentages are defined as the number of matches divided by the largest number between each pair of reanalysis. This shows that ERA-Interim has the largest number of matches for both and with about 78% of matches in (83% in) for each modern reanalysis, whereas the worst comparison occurs for JRA-25 with about 67% of matches in (75% in). Using ERA-Interim as a reference, the largest number of matches occurs for JRA-55, followed by NCEP-CFSR, MERRA-2, and JRA-25. For the most intense COLs (90% percentile), the number of matches in ξ300 (Z300) increases to 92.5% (87.8%) for JRA-55, 91.3% (89.4%) for NCEP-CSFR, 90.3% (89.3%) for MERRA2, and 85.5% (83.4%) for JRA-25 (not shown). This result is expected since the strongest COLs are more easily identified in reanalyses.

Also, the comparison between reanalyses show lower percentages of matches in winter than in other seasons for both and. The exception occurs for the MERRA-2 comparisons in that have the lowest percentages of matches in summer. This result contradicts the fact that the number of matches increases for the most intense systems, which are typically found in winter. A possible reason for the relatively low percentage of matches in winter may be due to the variable behavior of the COLs in the western Pacific which is a preferred region for both COL genesis and lysis (P17). This aspect may result in uncertainties due to the difficult task of identifying the COL lifecycle.

From the tracks that match, the distribution of the mean separation distances between each pair of reanalyses is constructed as shown in Fig. 7. This shows a positive skew distribution with the best matches occurring for the newest reanalyses. Most of tracks in the more recent reanalysis have mean separation distances less than 0.5° (geodesic) for and 0.7° for. The smallest values of separation distances in general occur for ERA-Interim, NCEP-CFSR, and MERRA-2. In contrast, JRA-25 has a broader distribution for separation distances than in the other reanalyses, indicating greater uncertainties in location of COLs which is consistent with the statistics shown in Figs. 2 and 3. The reason for the larger uncertainties in vorticity compared to geopotential may be related to the position of the centres in COLs. For symmetric systems, the maximum tends to appear near the low-pressure centre, as typically seen in surface extratropical cyclones. However, an elongated upper-level COL may shift the maximum equatorward as a consequence of the shear component (Bell and Keyser 1993), resulting in differences in location of centres.

Probability density distribution for mean separation distances for the tracks that match between the reanalyses ERA-Interim, NCEP-CFSR, MERRA-2, JRA-55, and JRA-25 for a\(\xi_{300}\) and b Cut-off lows. Analysis is performed for the latitudinal range 15º S–50º S for the 30-year period (1980–2009). Unit is degree geodesic

4 Discussion and concluding remarks

An intercomparison between five different reanalyses have been made based on the and COLs, with the aim of determining the differences and similarities between the reanalyses and the impact of the improvements in the data assimilation and forecast models used in the newer datasets (ERA-Interim, NCEP-CFSR, MERRA-2 and JRA-55) over those used in the older JRA-25. The numbers and the spatial distribution of COLs compare much better between the newer reanalyses than with the older JRA-25. For the track density, in particular the smallest differences were found for the comparison between ERA-Interim and JRA-55 as well as between NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2. These results are likely associated with the form that the data are assimilated, where ERA-Interim and JRA-55 both using 4D-Var, whereas NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2 use the 3D-Var GSI system.

Previous studies using older reanalyses have shown large differences in the COL seasonality, particularly for the SH (Reboita et al. 2010). The results presented here exhibit a strong similarity in seasonality between the reanalyses, even for the older JRA-25 reanalysis. Despite the agreement in seasonality, there are clearly large differences in numbers for the comparisons with the JRA-25, while the results obtained with the newest reanalyses compare well and are as good as those found for extratropical cyclones in both hemispheres (Hodges et al. 2011). Although the reanalyses are important to determine the number of identified COLs, the set of criteria used to detect a COL is found to be the most important factor in determining the seasonality, as shown in the recent study of Pinheiro et al. (2019).

A large variability of the and COLs in terms of annual numbers is shown, although no significant trends were observed. The best comparison occurs for the new reanalyses, particularly for the period starting from the 21th century, partly due to the improved assimilation of satellite radiances from infrared and microwave sounders and scatterometers for wind information. An absolute minimum in 2002 is observed for all reanalyses, which may be related to the anomalous event of a Sudden Stratospheric Warming. A positive but weak correlation between COLs and La Niña was found, i.e. COLs are found to be more common during the La Niña events. However, no evidence has been found between the El Niño and the COL activity, corroborating previous studies (Fuenzalida et al. 2005; Singleton and Reason 2007; Favre et al. 2012).

It was found that a strong relation is present between the distribution of maximum intensity of COLs and the reanalysis resolution. This is particularly the case in the distributions where NCEP-CFSR and MERRA-2 have the strongest COLs and JRA-25 has the systematically weakest COLs. This occurs because vorticity emphasises small-spatial scales which are more sensitive to the spatial resolution of reanalysis. In contrast, small differences in the values occur between the reanalyses even if the newer higher resolution reanalyses are compared with the older lower resolution JRA-25 reanalysis, indicating a larger reliability in representating the geopotential intensities of COLs.

The different statistics produced with the matched tracks show considerable improvement in the agreement between the new reanalyses compared to the older reanalysis. The best results were found for the comparison between ERA-Interim and JRA-55 with about 80% of matches but increasing to greater than 90% for the most intense COLs. This is much better than the comparison of the older JRA-25 reanalysis that has about 70% of matches, similar to previous findings (Hodges et al. 2003, 2011). The improvement of the new reanalyses over the older one is also apparent for the mean separation distances, with the matches having the majority of values around 0.5° (geodesic) for the comparison between the new reanalyses and greater than 1.0° for the comparison with the JRA-25, indicating a larger uncertainty in the location of COLs for the older reanalysis.

The overall impression is that the results obtained from the most recent reanalysis datasets are much better constrained than those from the older datasets, such as at high levels in the SH where the available observations are much sparser than in the NH. This progress provides more confidence in representing the COLs in the reanalyses, being also potentially useful for assessing climate models. However, uncertainties still persist with respect to the intensities of COLs, and it is difficult to quantify from the intercomparison presented here which reanalysis is closer to the reality due to the lack of a high-quality homogeneous verification data. More generally, further investigations could be undertaken to assess how reanalyses represent the precipitation associated with COLs. The use of remote sensing data such as the International Satellite Cloud Climatology Project (ISCCP) (Rossow and Schiffer 1991) and CloudSat (Stephens et al. 2002) satellite simulators could be an alternative to evaluate the precipitation estimated by the reanalyses studied in this paper together with new higher resolution reanalyses that are continuously being produced such as the ECMWF ERA5 reanalysis (Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) 2017).

References

Andrews DG, Holton JR, Leovy CB (1987) Middle atmospheric dynamics. Academic Press, New York, p 489

Baldwin MP, Dunkerton TJ (2001) Stratospheric harbingers of anomalous weather regimes. Science 294:581–584

Bell GD, Keyser D (1993) Shear and curvature vorticity and potential vorticity interchanges: interpretation and application to a cut-off cyclone event. Mon Weather Rev 121:76–102

Bengtsson L, Hodges KI, Hagemann S (2004) Sensitivity of large-scale atmospheric analyses to humidity observations and its impact on the global water cycle and tropical and extratropical weather systems in ERA40. Tellus A Dyn Meteorol Oceanogr 56:202–217

Bosilovich MG, Lucchesi R, Suarez M (2016) MERRA-2: File Specification. GMAO Office Note No 9 (Version 1.1), pp 1–75. https://gmao.gsfc.nasa.gov/pubs/docs/Bosilovich785.pdf. Accessed 02 Sept 2019

Butler AH, Sjoberg JP, Seidel DJ, Rosenlof KH (2017) A sudden stratospheric warming compendium. Earth Syst Sci Data 9:63–76

Campetella C, Possia N (2007) Upper-level cut-off lows in southern South America. Meteorol Atmos Phys 96:181–191

Cerrone D, Fusco G, Cotroneo Y, Simmonds I, Budillon G (2017) The Antarctic Circumpolar Wave: its presence and interdecadal changes during the last 142 years. J Clim 30:6371–6389

Charlton AJ, O’Neill A, Lahoz WA, Massacand AC, Berrisford P (2005) The impact of the stratosphere on the troposphere during the southern hemisphere stratospheric sudden warming, September 2002. Q J R Meteorol Soc 131:2171–2188

Compo GP, Whitaker JS, Sardeshmukh PD, Natsui N, Allan RJ et al (2011) The Twentieth Century reanalysis project. Q J R Meteorol Soc 137:1–28

Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) (2017): ERA5: Fifth generation of ECMWF atmospheric reanalyses of the global climate. Copernicus Climate Change Service Climate Data Store (CDS). https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/home. Accessed on 12 April 2019

Dee DP, Uppala SM, Simmons AJ, Berrisford P, Poli P et al (2011) The ERAI reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q J R Meteorol Soc 137:553–597

Ebita A, Kobayashi S, Ota Y, Moriya M, Kumabe R et al (2011) The Japanese 55-year reanalysis “JRA-55”: an interim report. Sola 7:149–152

Favre A, Hewitson B, Tadross M, Lennard C, Cerezo-Mota R (2012) Relationships between cut-off lows and the semiannual and southern oscillations. Clim Dyn 38:1473–1487

Fuenzalida HA, Sánchez R, Garreaud RD (2005) A climatology of cutoff lows in the Southern Hemisphere. J Geophys Res 110:D18101

Fyfe JC (2003) Extratropical Southern Hemisphere cyclones: Harbingers of climate change? J Clim 16:2802–2805

Grieger J, Leckebusch GC, Raible CC, Rudeva I, Simmonds I (2018) Subantarctic cyclones identified by 14 tracking methods, and their role for moisture transports into the continent. Tellus A Dyn Meteorol Oceanogr 70:1–18

Harvey BJ, Shaffrey LC, Woollings TJ, Zappa G, Hodges KI (2012) How large are projected 21st century storm track changes? Geophys Res Lett 39:L18707

Hodges KI (1996) Spherical nonparametric estimators applied to the UGAMP model integration for AMIP. Mon Weather Rev 124:2914–2932

Hodges KI (1999) Adaptive constraints for feature tracking. Mon Weather Rev 127:1362–1373

Hodges KI, Boyle J, Hoskins BJ, Thorncroft C (2003) A comparison of recent reanalysis datasets using objective feature tracking: storm tracks and tropical easterly waves. Mon Weather Rev 131:2012–2037

Hodges KI, Lee RW, Bengtsson L (2011) A comparison of extratropical cyclones in recent reanalyses ERAI, NASA MERRA, NCEP CFSR, and JRA-25. J Clim 24:4888–4906

Hodges K, Cobb A, Vidale PL (2017) How well are tropical cyclones represented in reanalysis datasets? J Clim 30:5243–5264

Hoskins JB, Hodges KI (2002) New perspectives on the Northern Hemisphere winter storm tracks. J Atmos Sci 59:1041–1061

Jones C, Carvalho LM (2013) Climate change in the South American monsoon system: present climate and CMIP5 projections. J Clim 26:6660–6678

Kalnay E et al (1996) The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 77:437–471

Kanamitsu M, Ebisuzaki W, Woolen J, Yang S-K, Hnilo JJ et al (2002) NCEP-DOE AMIP-II reanalysis (R-2). Bull Am Meteorol Soc 83:1631–1643

Keable M, Simmonds I, Keay K (2002) Distribution and temporal variability of 500 hPa cyclone characteristics in the Southern Hemisphere. Int J Climatol 22:131–150

Kentarchos AS, Davis TD (1998) A climatology of cut-off lows at 200 hPa in the Northern Hemisphere, 1990–1994. Int J Climatol 18:379–390

Kobayashi S et al (2015) The JRA-55 reanalysis: general specifications and basic characteristics. J Meteorol Soc Jpn Ser II 93:5–48

Kousky VE, Gan MA (1981) Upper tropospheric cyclonic vortices in the subtropical South Atlantic. Tellus 33:538–551

Kruger K, Naujokat B, Labitzke K (2005) The unusual midwinter warming in the Southern Hemisphere stratosphere 2002. J Atmos Sci 62:603–613

Limpasuvan V, Thompson DWJ, Hartmann DL (2004) The life cycle of the Northern Hemisphere sudden stratospheric warmings. J Clim 17:2584–2596

Marshall GJ, Stott PA, Turner J, Connolley WM, King JC, Lachlan-Cope TA (2004) Causes of exceptional atmospheric circulation changes in the Southern Hemisphere. Geophys Res Lett 31:L14205

Mitas CM, Clement A (2006) Recent behavior of the Hadley cell and tropical thermodynamics in climate models and reanalyses. Geophys Res Lett 33:L01810

Ndarana T, Waugh DW (2010) The link between cut-off lows and Rossby wave breaking in the Southern Hemisphere. Q J R Meteorol Soc 136:869–885

Newman PA, Nash ER (2005) The unusual Southern Hemisphere stratospheric winter of 2002. J Atmos Sci 62:614–628

Nieto R, Gimeno L, de la Torre L, Ribeira P, Gallego D, García-Herrera R et al (2005) Climatological features of cutoff low systems in the Northern Hemisphere. J Clim 18:3085–3103

Nieto R, Gimeno L, de la Torre L, Ribeira P, Barriopedro D, García-Herrera R et al (2007) Interannual variability of cut-off low systems over the European sector: the role of blocking and the Northern Hemisphere circulation modes. Meteorol Atmos Phys 96:85–101

Nieto R, Sprenger M, Wernli H, Trigo RM, Gimeno L (2008) Identification and climatology of cut-off low near the tropopause. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1146:256–290

Onogi K, Tsutsui J, Koide H, Sakamoto M, Kobayashi S et al (2007) The JRA-25 reanalysis. J Meteorol Soc Jpn Ser II 85:369–432

Orsolini Y, Randall C (2005) An observational study of the final breakdown of the Southern Hemisphere stratospheric vortex in 2002. J Atmos Sci 62:735–747

Pezza AB, Simmonds I, Renwick JA (2007) Southern Hemisphere cyclones and anticyclones: recent trends and links with decadal variability in the Pacific Ocean. Int J Climatol 27:1403–1419

Pinheiro HR, Hodges KI, Gan MA, Ferreira NJ (2017) A new perspective of the climatological features of upper-level cut-off lows in the Southern Hemisphere. Clim Dyn 48:541–559

Pinheiro HR, Hodges KI, Gan MA (2019) Sensitivity of identifying Cut-off lows in the Southern Hemisphere using multiple criteria: implications for numbers, seasonality and intensity. Clim Dyn 53:6699–6713

Piva ED, Gan MA, Rao VB (2008) An objective study of 500-hPa moving troughs in the Southern Hemisphere. Mon Weather Rev 136:2186–2200

Porcù F, Carrassi A, Medaglia CM, Prodi F, Mugnai A (2007) A study on cut-off low vertical structure and precipitation in the Mediterranean region. Meteorol Atmos Phys 96:121–140

Price JD, Vaughan G (1992) Statistical studies of cut-off low systems. Ann Geophys 10:96–102

Reboita MS, Nieto R, Gimeno L, Rocha RP, Ambrizzi T, Garreaud R, Kruger LF (2010) Climatological features of cutoff low systems in the Southern Hemisphere. J Geophys Res Atmos 115:D17104

Rossow WB, Schiffer RA (1991) ISCCP cloud data products. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 72:2–20

Rudeva I, Gulev SK, Simmonds I, Tilinina N (2014) The sensitivity of characteristics of cyclone activity to identification procedures in tracking algorithms. Tellus A Dyn Meteorol Oceanogr 66:24961

Saha S, Moorthi S, Wu X, Wang J, Nadiga S et al (2014) The NCEP climate forecast system version 2. J Clim 27:2185–2208

Simmonds I, Keay K (2000) Variability of Southern Hemisphere extratropical cyclone behavior, 1958–97. J Clim 13:550–561

Singleton AT, Reason CJC (2007) Variability in the characteristics of cut-off low-pressure systems over subtropical southern Africa. Int J Climatol 27:295–310

Stephens GL, Vane DG, Boain RJ, Mace GG, Sassen K et al (2002) The CloudSat mission and the A-Train: a new dimension of space-based observations of clouds and precipitation. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 83:1771–1790

Thompson DW, Baldwin M, Solomon S (2005) Stratosphere–Troposphere coupling in the Southern Hemisphere. J Atmos Sci 62:708–715

Trenberth KE, Mo KC (1985) Blocking in the Southern Hemisphere. Mon Weather Rev 113:3–21

Van Loon H, Jenne RL, Labitzke K (1973) Zonal harmonic standing waves. J Geophys Res 78:4463–4471

Varotsos C (2004) The extraordinary events of the major, sudden stratospheric warming, the diminutive antarctic ozone hole, and its split in 2002. Environ Sci Pollut Res 11:405–411

Wang X, Swail VR, Zwiers F (2006) Climatology and changes of extratropical cyclone activity: comparison of ERA-40 with NCEP–NCAR reanalysis for 1958–2001. J Clim 19:3145–3166

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecast (ECMWF), Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) for making the reanalyses datasets available for this study which are ERA-Interim, JRA-25 and JRA55, MERRA-2, and NCEP-CFSR. We also wish to thank the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and the University of Reading (England) for providing support throughout the preparation of this work. HP acknowledges funding from the CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) and CAPES (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel) for his research grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pinheiro, H.R., Hodges, K.I. & Gan, M.A. An intercomparison of subtropical cut-off lows in the Southern Hemisphere using recent reanalyses: ERA-Interim, NCEP-CFRS, MERRA-2, JRA-55, and JRA-25. Clim Dyn 54, 777–792 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-019-05089-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-019-05089-1