Abstract

Although the moisture feedback has been well known to be essential in the Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO) dynamics, whether its pre-moistening effect plays a key role in exciting the onset of primary MJO events, as has been confirmed in the successive initiation, remains elusive. In this study, using a hybrid coupled climate model that has a good fidelity in simulating the intraseasonal variability, we develop a new framework of methodology to investigate the nonlinear excitation of primary MJO event, of which the key achievement is the successful implementation of the conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation (CNOP). In an application of this new framework, the CNOP-type moisture perturbations are calculated for the pre-chosen non-MJO reference states and generally favor a moistening in the equatorial region while drying in the poleward. Comparisons of the model simulation with observation give credibility to the existence of moisture signals several weeks before some primary MJO events. A suite of numerical experiments confirms that the CNOPs of moisture can contribute to the excitation and propagation of strong primary MJO events while random perturbations cannot. The moisture budget analysis further reveals the central importance of the horizontal moisture advection, especially the nonlinearly upscaled moisture transports associated with the high-frequency disturbances on the quasi-3–4-day and 6–8-day synoptic time scales, in supporting the nonlinear excitation of the primary MJO events. The subgrid-scale processes of evaporation, condensation and eddy transport of moisture are found to be critical for the pre-moistening effect in the boundary layer as well. This study directly supports the vital importance of the moisture perturbations, which are characterized by a particular pattern concentrated at low levels, to the nonlinear growth and propagation of the primary MJO events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The most prominent variability in the tropics at the intraseasonal time scale (20–90 days) has been widely recognized as the Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO, Madden and Julian 1971, 1972). The composite life cycle of the MJO often manifests as firstly being initiated from the western Indian Ocean (WIO), moving eastward slowly (~ 5 m/s) with a locally unstable growth, peaking over the eastern Indian Ocean (EIO), and then crossing the Maritime Continent (MC) with a weakening to some degrees. When continuously propagating into the equatorial western Pacific (EWP) warm pool, it will re-develop and finally decay upon approaching the dateline (e.g., Madden and Julian 1972; Rui and Wang 1990; Wang and Rui 1990a; Hendon and Salby 1994; Wheeler and Hendon 2004; Zhang 2005; Lau and Waliser 2012). This “mobile”, equatorially convective heating in the MJO can strongly affect weather and climate worldwide, for example, it can significantly modulate the tropical cyclones genesis, heat and cold waves, drought and flooding, Asian-Australian monsoon system, and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Moreover, the MJO can also serve as an excellent predictability source on the sub-seasonal to seasonal (S2S) time scale (e.g., Ren et al. 2016; Ren and Ren 2017; Ren et al. 2018), and thus has the potential to fill the gap between the weather forecast and climate prediction. For more details, please refer to the comprehensive reviews by Zhang (2013), Serra et al. (2014), and Lee et al. (2017).

In the past several decades, although some great progress in understanding the dynamics and physics of the MJO have been frequently reported (e.g., Madden and Julian 1994; Zhang 2005; Li 2014; DeMott et al. 2015; Jiang et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2016; Ahn et al. 2017), there still exist some fundamental but unresolved scientific questions in which one of the most challenging and least studied aspects may be the initiation of the large-scale, deep convection and the planetary-scale circulation cells over the WIO associated with the MJO event (Ling et al. 2017; Zhang and Yoneyama 2017). Based on the past works, two major groups of thoughts can be generalized in understanding the MJO initiation: the internal origin from the deep tropics and the external forcing from the extratropics. The first group of thought consists of the dynamically Kelvin-wave response to the upstream (EWP)-moist and Rossby-wave responses to the downstream (EIO)-dry convective anomalies (e.g., Matthews 2000; Seo and Kim 2003; Zhao et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2014), the nonlinearly trio-interaction of localized radiation, convection, and surface fluxes (e.g., Bladé and Hartmann 1993; Hu and Randall 1994; Yu and Neelin 1994; Kemball-Cook and Weare 2001; Benedict and Randall 2007), and the dynamically and thermodynamically air-sea interactions (Li et al. 2008; Webber et al. 2010; Rydbeck et al. 2017). The second group highlights the key role of the intrusion of extratropical disturbances (e.g., Hsu et al. 1990; Ray and Zhang 2010; Adames et al. 2014; Sakaeda and Roundy 2015; Gahtan and Roundy 2019), such as the high-frequency (< 20 days) transients (Matthews and Kiladis 1999), the wave activity of mid-latitude Rossby waves (Zhao et al. 2013; Mei et al. 2015), the dry air (Kerns and Chen 2014), and cold surges (Hong et al. 2017). More recently, some studies even related the MJO initiation with the interaction between the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and the large-scale environments of lower-tropospheric wind and moisture (e.g., Ciesielski et al. 2018; Zelinsky et al. 2019).

These diverse viewpoints have reflected a large uncertainty associated with the MJO initiation, partially resulted from the highly episodic nature of the MJOs. Based on this sporadic timing of convective initiation, Matthews (2008) (denoted as M08 hereafter) classified each MJO event as either the successive type that is initiated by the previous MJO event or the primary type that occurs without any preceding eastward-propagating MJO signal. By composing the basic fields, such as the specific humidity, outgoing longwave radiation (OLR), temperature, divergence, and sea surface temperature (SST), associated with the all-seasonal events during 1974–2005, M08 concluded that the only significant precursor signal associated with the primary MJO initiation lies in the mid-tropospheric cold temperature anomaly associated with the in situ suppressed convective anomaly over the equatorial Indian Ocean (IO), but those mechanisms working well for the successive MJO initiation, including the dynamical effect of the upstream circumnavigating Kelvin wave (e.g., Matthews 2000), the pre-moistening effect of the shallow convection (e.g., Nasuno et al. 2015), and the leading warm SST anomaly (e.g., Li et al. 2008), are all absent. In a case study, however, Feng and Li (2016) showed that the onset of one primary event occurring during boreal winter of 2000–2001 results dramatically from the lower-tropospheric moisture accumulation of three types of equatorial perturbations, i.e., a weak MJO, an eastward-propagating Kelvin wave, and a westward-moving Rossby wave. Motivated by this case study, Wei et al. (2019) (denoted as W19 hereafter) further examined the moisture anomaly associated with each historical primary MJO event during boreal winter of 1979–2013, and found that slightly less than half of them was preceded by a westward-moving moist signal. This implies that the precursor signals or the most potentially preconditioning anomalies triggering the primary MJO initiation may involve the moisture.

Almost all the theoretical studies of the MJO prefer the linearized modeling frameworks (refer to Lau et al. 2012), mainly because these simplified frameworks can analytically represent and isolate different physical processes by the linearization. However, this is not always true for the primary MJO events, especially for their initiation stage. From a statistical point of view, for example, the MJO index should display a sharp growth from near zero to be enough strong (just exceed one standard deviation, STD) in a short duration, while once upon the triggering of eastward-propagating, planetary-scale MJO signal, the index evolves slowly and linear dynamics dominates (refer to Fig. 4 of Ling et al. 2013). From these arguments, we may make a conjecture that the nonlinearity should be key to the onset of primary MJO events. There have been some early attempts to explore the role of nonlinearity in the dynamics of low-frequency equatorial waves. For example, a nonlinear view of the MJO has been offered based on resonant triad interactions of a discrete set of planetary-scale waves (Kartashova and L’vov 2007). Due to the multiscale characteristics embedded in the planetary-scale MJO envelop (Nakazawa 1988), the nonlinear upscale transports of momentum, heat, and moisture associated with subplanetary-scale convection/wave activity were demonstrated to play a key role in the MJO dynamics (e.g., Majda and Stechmann 2009, 2011; Zhou and Li 2010; Zhu et al. 2019). The nonlinear dry Rossby wave dynamics was also tested to be fundamental to reproduce the eastward-propagating MJO-like structure (Wedi and Smolarkiewicz 2010). Using nonlinearity may offer a new idea to explain why almost all the spectrum variance of equatorial cloudiness can be predicted by the linear dry shallow water equation (Matsuno 1966; Gill 1980), except for the dominated peak associated with MJO (Wheeler and Kiladis 1999; Kiladis et al. 2009), although the moisture and its linear feedback to convective heating may also bring in extra solutions depicting the MJO (Adames and Kim 2016).

Utilizing the spectral density and wavelet analysis, Chen et al. (2015b) focused on the suppressed phase of the MJOs captured during the field campaign of the Dynamics of the MJO (DYNAMO) (Gottschalck et al. 2013; Yoneyama et al. 2013) and revealed a deep layer of vapor resurgence during the phases 5–8 of MJO as defined by the real-time multivariate MJO (RMM) index (Wheeler and Hendon 2004). They found that the nonlinear moisture transport associated with the high-frequency oscillating patterns, including the diurnal, quasi-2-, quasi-3–4-, quasi-6–8-, and quasi-16-day perturbations plays an essential role in the MJO initiation. By examining the third MJO event during the DYNAMO period as observed in December 2011, Kubota et al. (2015) found the advective pre-moistening effect of the westward-propagating disturbances with a 2-day period, which is consistent with the findings of Yu et al. (2018). More recently, using the in situ observation collected during the Year of Maritime Continent (YMC)-Sumatra 2017, Takasuka et al. (2019) found evidently westward-moving positive moisture and meridional wind disturbances of the quasi-3–8-day mixed Rossby-gravity waves preceding the onset of the December primary MJO event, validating their earlier findings using the aqua-planet experiments in Takasuka et al. (2018).

Motivated by the aforementioned reviews, we may assume that the moist initialization using a nonlinear model is capable to trigger the onset of primary MJO events. To validate this hypothesis, W19 have directly chosen a novel method of conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation put forward by Mu et al. (2003) and (2010), after extensively unsuccessful attempts to derive suitable linear solutions. With a preliminary study, W19 checked that the nonlinear optimal moist initialization is the potential to excite a new strong MJO event from a pre-chosen non-MJO reference state (NMRS). Inspired by W19, in this study, we developed a new methodology framework, aiming to reveal the vital importance of nonlinear moist processes, i.e., the nonlinearly upscale moisture transport associated with the synoptic-scale perturbations, in exciting the primary MJO events. This paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, we introduce the data and the hybrid coupled global climate model (CGCM) used here. We briefly review the conception of CNOP in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4, we will give a systematic and comprehensive introduction of our newly developed methodological framework for studying the primary MJO initiation. An application of this framework is shown in Sects. 5–6, including the solutions of the CNOPs of moisture (CNOP-m) (Sect. 5) and their potentialities in exciting the onset of primary MJO events (Sect. 6). In Sect. 7 we will devote our efforts to unravel the dominant physical processes that control the nonlinear excitation of primary MJO events. The last section summarizes our main findings and discusses some of their broader implications.

2 Data and model

2.1 Data

To measure the convective activity, we use the daily mean OLR data that is interpolated from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Advanced Very High-Resolution Radiometer satellite product (Liebmann and Smith 1996). The daily mean zonal and meridional winds (\(u\) and \(v\)), pressure velocity (\(\omega\)), and the specific humidity (\(q\)) are from the reanalysis data of the National Centers for Environmental Prediction/the National Center for Atmospheric Research (Kalnay et al. 1996). The time range analyzed here is from 1979 to 2013, and all datasets have been interpolated to a standard horizontal resolution of 2.5 °× 2.5° before analysis. For simplicity, we refer to them as “observations” throughout this paper.

2.2 The hybrid coupled global climate model

We use a hybrid CGCM that was originally developed by Fu et al. (2002), comprising the fourth-generation of ECHAM (ECHAM-4) atmospheric global climate model (Roeckner et al. 1996) coupled to an upper ocean model (Fu and Wang 2001) of intermediate complexity, with a coupling frequency of once per day. Over the global tropics (30°S–30°N), the full coupling is implemented by exchanging SST, surface wind stress and heat fluxes, whereas over the extratropics, the ECHAM-4 model is forced by the climatological SST and sea ice that retain only annual variations. The cumulus convection is parameterized using a bulk model including updraft and downdraft mass fluxes and considers shallow, mid-level, and penetrative convection (Tiedtke 1989). The radiation scheme was adopted from the model of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasting (ECMWF) (Fouquart and Bonnel 1980; Morcrette et al. 1986). The stratiform cloud water content is calculated from the budget equations including sources and sinks due to phase changes and precipitation. The oceanic model consists of a vertically uniform mixed layer, a thermocline layer with linearly decreasing temperature, and a motionless layer beneath the thermocline base.

The simulation uses the standard, triangular truncation with 42 spectra, that is, T42 (roughly 2.8° × 2.8°) version of ECHAM-4 model that resolves 19 vertical layers extending from the surface to 10 hPa, and the oceanic model is run with a horizontal resolution of 0.5° × 0.5° Although without using heat flux corrections, this CGCM displays a good fidelity in simulating the climatology and variability over the Asia-Pacific region, especially the intraseasonal oscillations (e.g., Fu et al. 2003; Fu and Wang 2004). As a universal representation of the MJO, for example, the modeled first two combined empirical orthogonal function (EOF) modes of OLR, zonal wind at 850 hPa (U850), and 200 hPa (Waliser et al. 2009) can bear a strong resemblance as that in observations (correlation > 0.88) (Figure not shown).

To study the primary MJO initiation using this CGCM, we should further examine the simulation fidelity associated with the initiation and propagation of primary MJO events. To make this point, we have selected 49 (32) non-overlapping primary MJO events initiated over the IO from observation (30-year free run of the CGCM). The methodology to identify primary events is the same as that proposed by M08. Figure 1 shows the composites of equatorially averaged (10°S–10°N), 20–90-day, bandpass-filtered OLR (shading) and U850 (contour) anomalies in observational data and CGCM’s simulation, respectively. As shown in M08 and Yong and Mao (2016), in Fig. 1a, there exists a weak, standing, suppressed convection over the central-eastern IO centered at day − 15 immediately preceding the onset of the large-scale, eastward-propagating (~ 5 m/s), deep convection. Besides, a planetary-scale easterly wind anomaly is also leading the primary MJO initiation, which is in good consistency with the findings reported by Straub (2013) and Ling et al. (2013). The suppressed convection over the western Pacific around lag 0 is the result of tropical-extratropical interaction rather than being originated from the propagation of the suppressed convection over the IO (Chen and Wang 2018a). All these observational features have been well reproduced by the CGCM (Fig. 1b), although the simulated primary event tends to be characterized by a more westward dispersive group velocity (~ 1 m/s) (Adames and Kim 2016; Chen and Wang 2018b) and an exaggerated “MC propagation barrier” (Zhang and Ling 2017; Fu et al. 2018).

Hovmöller diagrams of the composite, equatorially averaged (10°S–10°N) outgoing longwave radiation (shading, W m−2) and 850-hPa zonal wind (contour, m s−1) anomalies simulated from (a) observation and (b) coupled global climate model, respectively. The shading is shown with contour interval of 5 W m−2. The thick, solid (dashed) contour denotes the westerly (easterly) wind anomaly with interval of 0.5 m s−1, while the thin, solid lines represent the zero contours. The bottom axis is the longitude (degrees), whereas the left axis is the lead time (days). The dash magenta line shows the referenced phase speed of 5 m s−1. Day 0 denotes the time when the MJO convection reach the peak over the Indian Ocean

3 Conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation

Determination of the fastest-growing initial perturbations in predictability studies of weather and climate is of central importance, in which the linear approaches are widely used (e.g., Lorenz 1965; Buizza and Palmer 1995; Diaconescu and Laprise 2012). The motions of atmosphere and ocean, however, are essentially governed by the complicated nonlinear systems. The conventional linear theories can only suggest a fast-growing direction of sufficiently small perturbations in a short duration (Lacarra and Talagrand 1988; Tanguay et al. 1995; Mu 2000). To grasp the role of nonlinearity in the long-lasting (> 2 weeks) evolution of finite-amplitude initial disturbances, it is desirable and often necessary to deal with the nonlinear models themselves rather than their linear approximations. Based on these considerations, the CNOP method, which is a natural extension of linear singular vector to the nonlinear regime, was put forward (Mu et al. 2003). In the following, we use boldface to denote the multi-dimensional (> 2) matrix or vector, whereas those non-bold types represent the one-dimensional variables.

We describe the nonlinear motions of atmosphere and ocean as the following initial value problem:

where \(\varvec{S}_{0}\) is the initial value of the state vector \(\varvec{S}\) representing wind, temperature, humidity, and/or oceanic variables. \(\varvec{P}\) is model parameter vector that is independent with time \(t\), and \({\mathbf{\mathcal{B}}}\) is a nonlinear operator. We assume that Eq. (1) is well-posed, hence, for a pre-given forecast time \(T\) (> 0), the solution \(\varvec{S}_{T} = {\mathbf{\mathcal{M}}}_{T} \left( \varvec{P} \right)\left( {{\mathbf{S}}_{0} } \right)\) is well-defined, in which the parameter-dependent \({\mathbf{\mathcal{M}}}_{T} \left( \varvec{P} \right)\) is the propagator that propagating the initial value \({\mathbf{S}}_{0}\) to the forecast value \(\varvec{S}_{T}\). Let \(\varvec{S}_{T} + \varvec{s}_{T}\) be the solution of Eq. (1) with initial value \(\varvec{S}_{0} + {\mathbf{s}}_{0}\) and parameter value \(\varvec{P} + \varvec{p}^{\prime}\), in which \(\varvec{s}_{0}\) and \(\varvec{P} + \varvec{p}^{\prime}\) are the finite-amplitude initial perturbations of \(\varvec{S}_{0}\) and the departure from parameter \(\varvec{P}\), respectively. We have

The combination mode (\(\varvec{s}_{0\delta } ,{{\varvec{p}}^{\prime}}_{\sigma }\)) is called the CNOP (Mu et al. 2010) if and only if

where

Here, \(\varvec{s}_{0} \in C_{\delta }\) and \(\varvec{p}^{\prime} \in C_{\sigma }\) separately denote the constraint of initial perturbation and parameter perturbation, in which \(C_{\delta }\) and \(C_{\sigma }\) are closed convex sets with spherical radius of \(\delta\) and \(\sigma\), respectively. As stated in W19, a “perfect model” assumption, that is, letting the model parameter perturbation \(\varvec{p}^{\prime}\) be zero, has been used here. In this scenario, the optimization problem consisting of Eqs. (3) and (4) is reduced to

where we term the optimal initial perturbation \(\varvec{s}_{0\delta }^{I}\) as CNOP-I. With a true initialization, that is, \(\varvec{s}_{0} = 0\), we have the following optimization problem:

To distinguish with CNOP-I, we call such an optimal parameter perturbation in the constraint as CNOP-P. The CNOP method has been also extended to investigate the effects of boundary condition uncertainty (CNOP-B, Wang and Mu 2015).

In the past 15 years, the CNOP method has shown good advantages to linear methods across various fields of atmospheric and oceanic sciences (refer to the reviews by Mu and Duan 2005; Duan and Mu 2009; Mu et al. 2015). For example, it has been successfully used to explore the “spring predictability barrier” and target observation problems of ENSO (e.g., Mu et al. 2007, 2014; Tao et al. 2018), the stability of thermohaline circulation (Sun et al. 2005) and ecosystem (Sun and Mu 2011, 2016), the ensemble forecast of the tropical cyclones (Wang et al. 2011), and the optimally growing initial errors associated with the seasonal prediction of Kuroshio large mender (Wang et al. 2013). In this study, the CNOP method will be implemented and applied further to investigate the nonlinear optimal excitation of primary MJO events.

4 A new CNOP-based methodological framework

Benefiting from the CGCM, we have developed a new methodological framework to study the primary MJO initiation, with a successful implementation and application of CNOP and an intelligent differential evolution (DE) algorithm (Storn and Price 1997; Price et al. 2005). We will introduce this nonlinear framework step by step as follows.

4.1 Selecting the non-MJO reference states

Seen from Eq. (5), CNOP may display a strong sensitivity to the initial state \(\varvec{S}_{0}\) and its nonlinear evolution \({\mathbf{\mathcal{M}}}_{T} \left( \varvec{P} \right)\left( {\varvec{S}_{0} } \right)\). Thus, to calculate the optimal precursor exciting the primary MJO events, some distinctive NMRSs should be examined here. First, we identified “day 0” based on the time series of the 5-day running mean RMM amplitude when its minimum was met and also smaller than the one STD. Second, we chose such a period during which the RMM amplitude keeps smaller than a prescribed threshold of one STD from day 0 to 31. Third, the 5-day running mean of the OLR-based MJO index (OMI) (Kiladis et al. 2014) is further utilized to exclude those events with a weak RMM amplitude (< 1) but a strong convection (Straub 2013), viz., those that continuously maintain a high-amplitude (> 1) OMI lasting for more than 10 days. Using the above procedure and focusing on the extended boreal winter from 15 October to 15 May, a total of 8 NMRSs have been selected and half of them have been randomly chosen to be investigated in our study. The hovmöller diagrams of OLR and U850 were also examined (Figure not shown), but none of them shows the planetary-scale, organized, MJO signal. The re-forecasts will be started from day 0 of each NMRS. We will try to examine what type of initial perturbations can excite the strongest MJO events during the subsequent 41-day nonlinear evolutions.

4.2 Quantitatively defining the MJO

To make sure the feasibility of the CNOP method in investigating the MJO, which is characterized as a “mobile” system, we should first address the following question: how to quantitatively judge whether any MJO signal has been excited or not with a priori knowledge of only 42-day forecast? Motivated by Eq. (5), the MJO should be measured by the “energy” of the nonlinear evolutions in terms of initial perturbations. However, only transient information obtained at the forecast time \(T\) is not enough. Following Wang et al. (2015), we have used the 42-day zonal wavenumber-frequency spectra (Wheeler and Kiladis 1999; Kiladis et al. 2009) of convection and circulation to construct an energy-based metric of the MJO in the frequency domain, which can well consider the “time accumulation effect” of initial perturbations, as follows:

This formula involves the accumulated power spectrum of OLR (\(i = 1\)), U850 (\(i = 2\)), and coherence square between them (\(i = 3\)). \(\rho_{i}\) (\(\in \left[ {0, 1} \right]\)) is the weight coefficient, by which one can easily explore the MJO initiation identified by the excitation of slowly eastward propagating, large-scale cloudiness signals (\(\rho_{1} \gg \rho_{2}\)), or planetary-scale, dynamical circulation signals (\(\rho_{1} \ll \rho_{2}\)), or the simultaneous development of well-organized convection anomalies and circulation cells (\(\rho_{1} \approx \rho_{2}\)). Here, we take \(\rho_{1} = \rho_{2} = \rho_{3} = 1/3\), which can guarantee a more precise definition of MJO initiation that considers initiation of a tight coupling between circulation and convection. \(P_{i} \left( {\omega ,k} \right)\) is the spectral variance at frequency \(\omega\) and zonal wavenumber \(k\). \(\left( {\omega ,k} \right)\) (\(\in \varOmega_{MJO} = \left[ {0, 3} \right] \times \left[ {1/100, 1/20} \right]\)) outline the spatial-frequency range of eastward-propagating MJO signal. To satisfy the additivity, a pre-normalization by \(\pi_{i}\), which denotes the STD of total power spectrum variance in \(\varOmega_{MJO}\), is necessary. It is remarkable that, under the “perfect model” assumption, \(I\) is totally controlled by the initial conditions of each individual NMRS.

4.3 Assuming that moisture triggers primary MJO initiation

Another question to be addressed when using the CNOP method is: what are the most potential precursor signals or variables that can trigger a primary MJO initiation from the pre-chosen NMRS? In this study, the moisture triggering primary MJO initiation has been assumed, which has been justified as follows. (1) The moisture feedback under a weak temperature gradient approximation can successfully simulate some realistic features, including the unique westward energy dispersion, of the MJO (e.g., Adames and Kim 2016), though neglecting the wave feedback. (2) The significant role of the pre-moistening effect in the MJO has been revealed by a large number of observational and numerical studies (e.g., Benedict and Randall 2007; Nasuno et al. 2015; Feng and Li 2016; Wang et al. 2018a). (3) Improved skill in the MJO prediction with optimally moist initialization has been shown (e.g., Ham et al. 2012).

The next step is to choose the possible initiation location of the MJO events (Zhang and Yoneyama 2017). With an exclusive preference over the warm ocean, the MJO initiation may occur over the tropical IO, MC, EWP, and the tropical Atlantic (M08; Baranowski et al. 2017). We examine the three-dimensional (3-D) distribution of the variance associated with the 90-day highpass-filtered specific humidity, with a tacit assumption that the role of low-frequency (> 90 days) basic state is minor in triggering the large-scale deep convective initiation on the intraseasonal time scale (20–90 days). We use this assumption to highlight a non-varying mean state during the 42-day optimization time range, which is essentially different from Ray et al. (2011) who demonstrated that the error in the mean state could be sufficient to prevent the MJO initiation. The results show that the variance prefers the Indo–Pacific region and aggregates over the lower troposphere (500–1000 hPa) (see Fig. 2). Therefore, we choose the precise region for the extraction of possible precursor signals based on the areas with large moisture variance, in particular, the equatorially symmetric IO region from 15°S to 15°N, from 40° to 110°E, tiered vertically at 1000, 925, 850, 700, 600, and 500 hPa. Using only six pressure levels can effectively reduce our optimization problem constructed as follows and save the computation resource. We excluded the southeast Indian Ocean region with large variance, because the climatological mean easterly wind prevails over there and plays a minor role in promoting the moist perturbation into the deep tropics and helping initiate the primary MJO events.

Three-dimensional domain (refer to the cube outlined by the thick black lines) to perform EOF analysis and extract the possible moisture precursor signals triggering the primary MJO initiation. a Horizontal map of the variance associated with the 90-day, highpass-filtered, lower-tropospheric, specific humidity (g kg−1). b Longitude-pressure section of equatorially averaged (10°S–10°N) moisture variance. c Vertical profile of the domain-averaged (10°S–10°N, 40°–110°E) moisture variance. Here, to further reduce the dimensionality of our nonlinear optimization problem, only six representative pressure levels are used, that is, 1000 hPa, 925 hPa, 850 hPa, 700 hPa, 600 hPa, and 500 hPa

4.4 Constructing the nonlinear optimization problem

Building on the procedures from steps a to c, we then can construct the nonlinear optimization problem for studying the primary MJO initiation. We let \(\varvec{Q}_{0}\) be the initial specific humidity of the pre-chosen NMRSs, and \(\varvec{q}_{0}\) be a finite-amplitude disturbance of \(\varvec{Q}_{0}\), i.e., \(\parallel \varvec{q}_{0} \parallel \le \alpha\). We term “ctr” and “per” as the numerical integrations initiated from \(\varvec{Q}_{0}\) and \(\varvec{Q}_{0} + \varvec{q}_{0}\), respectively. From Eq. (7), we can get:

Note that although \(I\) is calculated from the spectrum of OLR, U850, and coherence between them (Eq. 7), it should originally vary as a function of initial moisture conditions. According to Eq. (8), contributions of the initial moist perturbations \(\varvec{q}_{0}\) to the excitation of primary MJO events can be derived as

From Eq. (9), a stronger MJO event should correspond to a larger value of \({\mathcal{J}}\). Thus, the problem of searching for the optimal moist precursor \(\varvec{q}_{0\alpha }\) that can excite the strongest primary MJO event is transformed to the following constraint nonlinear optimization problem:

Equation (10) implies that the optimal moist precursor just corresponds to the global optimal point in the domain \(\parallel \varvec{q}_{0} \parallel_{\alpha } \le \alpha\), that is, CNOP-m.

4.5 A combined space reduction-DE solving technique

To effectively solve the nonlinear optimization problem consisting of Eqs. (9) and (10), we have developed a combined space reduction-DE solving technique. To reduce the dimensionality of space, we have utilized the EOF-based strategy (e.g., Xue et al. 1994, 1997a, b; Chen et al. 2015a; Oosterwijk et al. 2017). The EOF decomposition of the 90-day highpass-filtered specific humidity is performed over the MJO initiation region (refer to the description in step c). The first 50 principal components (PCs), which are well separated from each other and can explain more than 80% of the total variance, are used here to span the original space. Any initial state \(\varvec{Q}_{0}\) can be projected orthogonally onto the N-dimensional (N = 50) subspace as:

where

denotes the projection coefficient vector, whereas

is the sparse matrix that consists of the first \(N\) EOF modes \(\varvec{e}_{j} \left( {j = 1, \ldots ,N} \right)\). Finally, the optimization problem (step d) is converted as

and

in which, \(\widetilde{{ \in_{0} }}\) is the finite-amplitude perturbation of \(\in_{0}\), that is, \(\parallel \in_{0} \parallel_{ \in } \le \beta\). The value of \(\beta\) (= 0.15) is given based on the previous observational diagnostic studies (e.g., Zhao et al. 2013; Li et al. 2015; and many others), in which the magnitude of the composite moisture anomaly during the pre-onset stage of MJO events is about 0.1 g kg−1, which can be well met when specifying the value of \(\beta\) being smaller than 0.3. To facilitate the following discussion, we still call the optimal projection coefficient vector \(\widetilde{{ \in_{0\beta } }}\) as CNOP.

To calculate the CNOP using the canonical gradient-based algorithms, the gradient information of the cost function in terms of initial perturbation, that is, \(\frac{{\partial {\mathcal{L}}}}{{\partial \widetilde{{ \in_{0} }}}}\), should be firstly estimated. Without the adjoint version of the CGCM, instead, we have directly computed the difference quotient of \({\mathcal{L}}\) in terms of \(\widetilde{{ \in_{0} }}\), namely \(\varvec{G} = \frac{{\Delta {\mathcal{L}}\left( {\widetilde{{ \in_{0} }}} \right)}}{{\Delta \widetilde{{ \in_{0} }}}} = \frac{{{\mathcal{L}}\left( {\widetilde{{ \in_{0} }} + \Delta \widetilde{{ \in_{0} }}} \right) - {\mathcal{L}}\left( {\widetilde{{ \in_{0} }}} \right)}}{{\Delta \widetilde{{ \in_{0} }}}}\), in which \(\Delta \widetilde{{ \in_{0} }}\) is a small perturbation of \(\widetilde{{ \in_{0} }}\). To check if the gradient exists or nor, we used the following formula,

where the operator \(\parallel \cdot \parallel\) denotes calculating the L2 norm. The numerical experiments results showed that \(R\) did not converge to 1 with the decreasing of \(\alpha\) (Figure not shown), which proved the inexistence of \(\varvec{G}\), presumably resulted from the nonlinear advection processes and/or the “ON-OFF” parameterization of tropical cumulus convection. Thus, the gradient-free algorithm, e.g., the DE algorithm (Storn and Price 1997) (see the brief introduction of DE algorithm in the Appendix), has been implemented here, and its global convergence has been checked by Price et al. (2005).

4.6 Experimental strategy

A series of numerical experiments have been carried out in the implementation and application of this new methodological framework. For example, for each NMRS, several distinctive groups of initial population have been input to the DE algorithm, through which the possibility of finding the global optimal point will increase. After 15–20 iterations, each group of initial guess value can reach a convergent solution with a fixed value of cost function. According to Eq. (14), the maximum value in the several convergent solutions is identified as the CNOP. To further validate the global convergence of CNOP, we have also chosen 600 initial random perturbations (RP) from the feasible region \(\left\{ { \in_{0} |\parallel \in_{0} \parallel_{ \in } \le \beta } \right\}\). But, none of them can induce a larger value of cost function than CNOPs.

Next, we substitute the CNOPs into the model initial conditions, to check their ability to trigger the initiation of primary MJO events. Specifically, we have made three reforecasts: (1) Control run, in which the unperturbed initial conditions have been used; (2) CNOP run, with CNOP-perturbed initial conditions; (3) RP run, which is the same as CNOP run, except for the random perturbations. For more details of these numerical experiments, one can refer to Table 1. To facilitate comparison, we scale any random perturbations to have the same norm as the CNOPs. The role of the CNOPs in exciting the primary MJO events is then revealed by comparing the three runs.

5 CNOPs of moisture

5.1 Three-dimensional distribution

Despite the central importance of moisture effect in MJO dynamics (e.g., Sobel et al. 2001; Raymond and Fuchs 2009; Sobel and Maloney 2012, 2013; Adames and Kim 2016), we still cannot identify some days early what kinds of anomalously preceding moisture patterns have the most potential to excite the onset of the immediately following primary MJO event. If CNOP-m can work well, the 3-D structures of CNOP-m should be unique with a physical significance, at the very least compared with that of random perturbations. Figure 3 shows the 3-D, that is, the zonal, meridional and vertical distributions of CNOP-m calculated from all four NMRSs. Seen from the vertical profiles in Fig. 3c, a coherent moistening aggregates in the lower-level troposphere, especially near the 850 hPa. However, in the boundary layer (BL), the perturbations are somewhat weak. Meridionally (Fig. 3b), the mean of CNOP-m shows dramatically positive anomalies straddling the equator (5°S–5°N). Negative anomaly towards the poles is also visible in the individual cases, as can be seen from the uncertainty of mean value. Along the equator (Fig. 3a), we can see that the signals over the WIO are stronger than those over the EIO. This kind of moist perturbations will firstly destabilize the equatorially lower-layer atmosphere, thus offering the potentiality to excite a new equatorially trapped deep convection of the MJO.

5.2 Validity in capturing the pre-moistening signals of primary MJO events

Considering that the CNOP-m have been artificially calculated from the nonlinear optimization problem, its capability in capturing the pre-moistening signals of primary MJO events should be validated further. W19 has revealed that 23 out of 49 observed primary events were preconditioned by evident moisture signals (refer to their Fig. 2) and used composite analysis demonstrated that such moisture signals originate from the equatorial EIO, and move toward the WIO. The horizontal structure and vertical distribution also bear a strong resemblance with that of CNOP-m, confirming the reality of CNOP-m. Upon approaching the East Africa, the moist precursor signals undergo a localized growth, possibly due to the topographic forcing over there (Hsu and Lee 2005), while then reversely propagate towards the east, helping excite the following primary MJO event. These findings are somewhat similar with the idea of “Rossby wave reflection” as suggested by Roundy and Frank (2004). More in-depth observational and modeling studies, however, are still necessary to make it sense in the future.

Are the 20 primary MJO events during boreal winter simulated from the CGCM always preceded by such signals as the CNOP-m? To address this question, in Fig. 4a–d, we show the time evolution of the 20–90-day filtered OLR anomaly over 10°S–5°N, 60°–90°E of a randomly chosen primary MJO event. Day 0 was defined as the date when the peak convection was met, whereas the convective initiation date was defined when the one STD of OLR anomaly was met. We calculated the pattern correlation coefficient (PCC) between CNOP and 90-day highpass filtered specific humidity anomaly over the three-dimensional domain used to calculate the CNOP (see the cube in Fig. 2). The PCC in Fig. 4a–d is shown using circles that are proportional to the PCC, in which the positive (negative) PCC is shown with a red (blue) circle. For this randomly chosen MJO case, we can see that strong positive (negative) PCCs calculated based on CNOP2 to CNOP4 aggregate during the Pre-onset (Post-onset) stage. However, the PCC calculated based on CNOP1 is dominated by the negative value aggregating during the Pre-onset stage. These results suggest that this randomly chosen primary MJO event tends to have moist precursors more like CNOP2–CNOP4 rather than CNOP1.

Time evolution of domain-averaged (10°S–5°N, 60–90°E) OLR (W/m2) anomaly for a randomly chosen primary MJO event in the CGCM. The circle in each day denotes the pattern correlation coefficient (PCC) between CNOP1 and 90-day highpass filtered specific humidity anomaly of this randomly chosen MJO case over the three-dimensional domain used to calculate CNOPs (see the cube in Fig. 2). The PCC is proportional to the circle diameter, and the red (blue) circle denotes positive (negative) PCC. The horizontal dashed line represents the one standard deviation (STD) of 20-90-day bandpass filtered OLR anomaly over 10°S–5°N, 60–90°E. The “Pre-onset” (“Post-onset”) stage is defined when the OLR anomaly is larger (smaller) than the one STD. (b–d) Same as (a), but for the CNOP2, CNOP3, and CNOP4, respectively. e Scatter diagram showing the averaged PCC calculated based on CNOP1 during the Pre-onset stage as a function of that during the Post-onset stage, in which the red dots denote that (1) the mean PCC during the Pre-onset stage is positive and (2) the Pre-onset stage has a larger mean PCC than the Post-onset stage, while the blue dots denote that the Pre-onset stage has a smaller mean PCC than the Post-onset stage. Each dot represents each primary MJO event. f–h Same as (e), but for the CNOP2, CNOP3, and CNOP4, respectively. “%” denotes the percentage of red dots in the whole dots, implying the ratio of primary MJO cases having CNOP-like moisture precursor signals

To quantitatively understand the extent to which the CNOP-m can represent the “true” precursors of primary MJO initiation in a robust manner, we examined the results like that in Fig. 4a–d for each primary MJO event and showed the averaged PCC during the Pre-onset stage as a function of that during the Post-onset stage in Fig. 4e–h. An event has a CNOP-type moist precursor should meet the following two criterions: (1) the mean PCC during the Pre-onset stage is positive and (2) the Pre-onset stage has a large mean PCC than the Post-onset stage. The first criterion guarantees that there should, at least, exist some moisture signals like the CNOP-m during the Pre-onset stage. However, a positive mean PCC may also occur during the Post-onset stage (see the Fig. 4a). With an extra restriction from the second criterion, we further guarantee that the majority of positive PCCs just aggregate during the Pre-onset stage (just like those shown in Fig. 4b–d). Those primary MJO events meeting both of the above two criterions are shown in red dots, while the blue dots denote the rest primary MJO events, for which one or both of the two criterions cannot be met. As we can see, the red dots in Fig. 4g are more than the blue dots, which implies that the majority of primary MJO events have moist precursors like CNOP3 (60%, 12 out 20 cases). The CNOP2 (Fig. 4f) and CNOP4 (Fig. 4h) also have a strong potential to explain the moist precursor signals of 40% (8 out of 20 cases) of the primary MJO events. Although there are only two primary MJO events that have CNOP1-type moist precursor signals (Fig. 4e), when we substituted the CNOP1 into the initial condition of the first randomly chosen NMRS (i.e., case 1), a strong primary MJO event was be still excited, which strongly suggests that the CNOP1, although not as that representative as the CNOP2–CNOP4, can also serve as a potential moisture precursor signal triggering the primary MJO initiation, as least compared with the random perturbations (refer to the following sections).

More worth noted is that although the individual CNOP cannot explain all of the primary MJO events, 85% (17 out of 20 cases) of these events always have moisture precursor signals like at least one of the four CNOPs (see Table 2). This implies that the CNOP-m can do serve as a potential nonlinear optimal precursor signal triggering the primary MJO initiation, at least during the boreal winter and in this CGCM, which will be confirmed in the next section using a suite of reforecast experiments.

In summary, based on both the observational and modeling diagnostic analyses, we confirmed the reality of our CNOP-m in representing the “true” moist precursors of the majority of primary MJO events, especially the role of CNOP2, CNOP3, and CNOP4.

6 Nonlinear optimal excitation of primary MJO events

To keep in a good consistency with the first two steps of our new methodological framework, in this section, we will examine both the zonal wavenumber-frequency spectrum and time evolutions of the OMI and RMM index to check whether the CNOP-m, which is characterized with inimitably spatial pattern, can excite the strongest MJO event than those randomly distributed perturbations. Besides, the organization and propagation of circulation and convection are also diagnosed here.

6.1 Zonal wavenumber-frequency spectrum

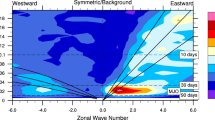

Figure 5 shows the zonal wavenumber-frequency spectra of equatorially averaged (10°S–5°N) OLR anomalies simulated from the Control, CNOP, and RP runs. It is interesting to note that, when focusing on one given NMRS, the CNOP run always exhibits the strongest power variance of OLR, especially that over \(\varOmega_{MJO}\). In the RP run, however, it shows some degrees of uncertainty. For example, over \(\varOmega_{MJO}\), the OLR variance has increased in cases 1–2 while decreased in cases 3–4, compared with that of Control run. The contrasting spectrum between the CNOP and RP runs implies that the CNOP-m, which is characterized by a unique 3-D structure with a physical significance, can do excite a robust signal oscillating at the intraseasonal time scale (20–90 days), and organizing on the planetary and subplanetary zonal scales (wavenumbers 0–4).

Zonal wavenumber-frequency spectrum of OLR simulated from the (Left) Control, (Middle) CNOP, and (Right) RP runs, respectively. The bottom axis denotes the zonal wavenumber (2π/40,000 km), whereas the left axis represents the frequency (cycles per day). The shading is shown from 20% of the maximum. (a–c) Case 1, (d–f) Case 2, (g–i) Case 3, (j–l) Case 4

Now we focus on the inter-comparison of the CNOP runs among the four NMRSs. We can see that the variance patterns of the OLR have actually a clear case dependence, which can be justified from the following two aspects. (1) Amplitude, the signal in case 2 is the strongest with the maximum OLR variance can exceed 40 W2/m4, while the weakest signal occurs in case 3 with a maximum of less than 25 W2/m4. Signals in cases 1 and 4 are moderate, and the peak variance is larger than 30 W2/m4. (2) Preferred zonal scale, in cases 2–3, the OLR variance tends to prefer the planetary scales (wavenumbers 0–2). In cases 1 and 4, however, the spectral energy is largely reduced at planetary zonal scales while enhanced at high wavenumbers (wavenumbers 3–4). Despite a large dissimilitude in the above two aspects, all the four NMRSs tend to prefer a unified oscillating frequency, peaking at 0.02 cycles per day (i.e., period of 50 days), well consistent with the statistical features of the observed intraseasonal variability (e.g., Madden and Julian 1971, 1972). Using the frequency and wavenumber, one can easily predict that the CNOP-m may also trigger different wave phase speeds, in which the fastest propagation occurs in cases 2–3, while signals in cases 1 and 4 propagate more slowly.

We also examined the spectra of U850 and the coherence square between OLR and U850 (Figures not shown). The results showed that a planetary zonal scale selection of circulation (Li and Zhou 2009; Wei et al. 2017) and a tight coupling between convection and circulation (Zhang 2005) associated with the MJO were also well simulated only in the CNOP runs, implying the superiority of CNOP-m in exciting the MJO signals.

6.2 Time evolutions of OMI and RMM index

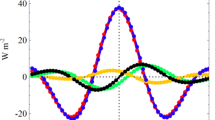

Now that the OMI and RMM index have been used to select NMRSs, we should also examine their time evolutions to determine whether there have been strong MJO events initiated by the CNOP-m. Figure 6 shows the 42-day time evolutions of the amplitudes of the two indices as simulated from the Control (black), CNOP (red), and RP (blue) runs, respectively. We can see that both the RMM index (Fig. 6a) and OMI (Fig. 6b) are very weak (amplitude < 1) in the Control run. In the RP run, although the mean amplitude has been amplified by the random perturbations, there exists the only excitation of short-duration synoptic-scale events, that is, non-MJO events (Ling et al. 2013). However, when NMRSs were initialized by the CNOP-m, both of the indices grow quickly and exceed the one STD threshold of MJO initiation, on average, after 10-day nonlinear evolutions. In addition, as shown in Fig. 6, a large spread exists in terms of the MJO’s initiation time, amplitude, and even duration, which reflect the intrinsic diversity of the MJO (Wang et al. 2019a, b; Wei and Ren 2019).

Time evolutions of the a RMM index and b OMI simulated from the Control (green), RP (blue), and CNOP runs (red), respectively. The bottom axis is the lead time (in days), whereas the left axis is the amplitude. The thick solid lines show the mean of the indices, and the shading represents the uncertainty of mean. The marker denotes result at that day

6.3 Organization and propagation of convection and circulation

The last step in confirming the MJO initiation is to examine the organization and propagation of convection and circulation in different reforecasts. The method is very similar to that used by Jiang et al. (2015) and Wang et al. (2018a). Keep in mind that, to clearly observe the convective initiation process of MJO events which conceptually consists of Pre-onset, Onset, and Post-onset stages (Stephens et al. 2004), the integration time has been extended to 62 days. A lagged regression field, with a maximum lag of 15 days, is firstly obtained by regressing the 62-day forecasts onto the negative RMM2 index (the second component of RMM index). Then we compose all the regression fields across different NMRSs.

Figure 7 shows the spatiotemporal evolutions of the composites of OLR and 850-hPa wind anomalies in the three runs. As predicted from their small evolutions of OMI and RMM index (refer to Fig. 6), in the Control and RP runs, both the convection and circulation manifest as non-organized and standing anomalies, therefore, no MJO events are initiated. Interestingly, in the CNOP run, a localized enhanced convection can be clearly observed over the southwestern IO at day − 15. Subsequently, this convective anomaly keeps growing, expanding, and also propagating slowly eastward (~ 5 m/s). Since day 5, the active convection tends to detour from the southern MC (Kim et al. 2017), and then propagates into the EWP. Just like those typical MJO cycles (e.g., Rui and Wang 1990; Hendon and Salby 1994; Wheeler and Hendon 2004; Matthews 2008), since lag 0, a suppressed convection is also initiated over the southwestern IO, and shows a similar evolution as the active convection. The lower-tropospheric winds are also tightly coupled with convection, forming a mixed Rossby-Kelvin wave structure (Wang and Rui 1990b; Kang et al. 2013; Wang and Chen 2017; Wang et al. 2018b).

In the CNOP run in Fig. 7, we can also observe clear suppressed convection propagating eastward and leading the deep convection initiation, which may lead one to treat it as successive MJO initiation. However, all the MJO events in the CNOP run have developed from non-MJO to MJO states (See Fig. 6), which was a typical excitation of primary MJO events according to the definition of previous studies (e.g., Straub 2013; Ling et al. 2013). To justify this point, we also examined the RMM phase diagrams of each case (Figure not shown). The results showed that the cases 1, 3, and 4 did manifest as canonical primary MJO initiation as defined in M08, in which the active convection was firstly triggered over the eastern Africa and western Indian Ocean. For the case 2, the convection also evolved from non-MJO to MJO state but displayed the first excitation of suppressed convection, which was a non-canonical primary-type initiation of MJO events mentioned in Fu et al. (2015)

Although the 3-D structure of CNOPs tends to be similar in different cases, especially that near the equator (Fig. 3), they still very likely excite very different primary MJO events due to (1) large spread in the CNOP ensembles and (2) the difference in the background states from which they were solved and evolved. With time, the initial subtle differences may be amplified enough to trigger distinctive primary MJO initiation. In case 2, the entire IO showed a pronounced cold SST anomaly, which occurs as a remote response to the La Niña phenomenon occurring over the central-eastern Pacific. However, in cases 1, 3, and 4, the SST anomalies over the equatorial IO were very weak (Figures not shown here).

7 Moisture budget analysis

Because MJO events have been exclusively excited by the CNOP-m, a moisture budget analysis is conducted here to reveal the dominant physical processes leading to the primary MJO initiation. Following Yanai et al. (1973), we write the moisture tendency equation at a constant pressure level as:

where \(\varvec{q}\) is the specific humidity, \(t\) is time, \(\varvec{V}_{h} = \left( {\varvec{u}, \varvec{v}} \right)\) is the horizontal wind vector, \(\nabla_{h} = \left( {\partial /\partial x, \partial /\partial y} \right)^{T}\) is the horizontal gradient operator, \(\varvec{\omega}\) is the vertical pressure velocity, \(p\) is pressure, \(\varvec{Q}_{2}\) is the apparent moisture sink of atmosphere, and \(L_{v}\) is the latent heat of condensation. Of interest is the 20–90-day intraseasonal time scale, thus, a 20–90-day bandpass filtering (denoted by a prime) has been applied to each term of Eq. (17). The first two terms on the right-hand side of Eq. (17) are the horizontal and vertical advection, respectively. The third term is the moisture sink, which include the subgrid-scale evaporation, condensation and eddy transport of moisture associated with the congestus (Yanai et al. 1973; Adames 2017; Hung and Sui 2018) and can be evaluated as the residual between the moisture tendency and the sum of all advection terms (e.g., Yanai et al. 1973; Hsu and Li 2012; Adames et al. 2016).

Figure 8 shows the lagged composite of the equatorially averaged (10°S–5°N) moisture and its temporal tendency, and OLR anomaly from the day − 15 to day 0 in the 5-day interval. At day − 15 in the CNOP run (Fig. 8b), a shallow, lower-tropospheric moisture anomaly can be observed over the WIO. More interestingly, centered on this shallow moisture anomaly, the moisture tendency manifests a clear zonal asymmetry, where the moistening tends to occur to the east of moisture center whereas the drying occurs to the west. This kind of zonal asymmetry has been suggested to be fundamental in destabilizing the MJO and dragging it to propagate eastward (e.g., Hsu and Li 2012; Hsu et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2017; Wei and Ren 2019). As seen from days − 10 to − 5, the preceding localized moisture anomaly has been intensified and pulled eastward slowly (~ 5 m/s) as a result of the continuous evolution and propagation of zonal asymmetry in moisture tendency. All of the above features are absent in the Control run (Fig. 8a), thus leading to non-growing, standing perturbations. These contrasting spatiotemporal evolutions of moisture perturbations, especially the zonal asymmetry of their temporal tendencies, have determined that the MJO initiation would occur in the CNOP run rather than the Control run.

Lagged composites of equatorially averaged (10°S–5°N) specific humidity (contour, g kg−1), moisture tendency (shading, 1 × 10−6 g kg−1 s−1), and OLR (color areas, W m−2) anomalies simulated from the a Control and b CNOP runs, respectively. The contours start from ± 0.5 g kg−1 with interval of 1.0 g kg−1, the thin solid lines denote the zero contour. The x-axis is longitude (°), while the y-axis is pressure (hPa) for contour or OLR (W m−2) for color area

To examine the role of CNOP-m in moistening the column, we calculated the vertical profiles of the difference of total moisture budget between CNOP run and Control run, and the results are represented in Fig. 9. To focus on the Pre-onset stage of primary MJO initiation, the time-averaged (days − 15 to − 5) results over the MJO initiation region (10°S–5°N, 60–90°E) have been shown here. As one can see from Fig. 9, the CNOP-m can induce a coherent net moistening in the free troposphere and BL (see the moisture tendency shown by black curve), with the maximum located near 500–800 hPa. Despite displaying a net drying in the BL, the horizontal advection (thick red curve) is still the dominant term contributing to the net moistening in the free troposphere. However, the vertical advection (blue curve) has led to a net drying effect throughout the lower troposphere and BL. The same as some previous studies (e.g., Kim et al. 2014; Hung and Sui 2018; Wei and Ren 2019), the net moistening associated with the subgrid-scale processes of condensation, evaporation and eddy transport of moisture has been largely canceled by the vertical advection, especially in the BL. By decomposing the horizontal advection into its zonal (solid red curve) and meridional (dashed red curve) components, we found that the primary contributor to the lower-level moistening is the meridional advection peaking around 650–800 hPa, whereas the zonal advection only contributes to the net moistening centered at 500 hPa.

Vertical profiles of the time-averaged (days − 15 to 5) totally moisture budget results (1 × 10−6 g kg−1 s−1) over the MJO initiation location (10°S–5°N, 60°E–90°E), which is calculated as the difference between the CNOP run and Control run. The thick lines show the moisture tendency (black), horizontal advection (red), vertical advection (blue), and column processes (green), respectively. The thin red solid line is the zonal advection, while the thin red dashed line is the meridional advection

To investigate the role of multiscale interactions of the high-frequency, intraseasonal, and low-frequency anomalies, especially that of the nonlinearity, in exciting the primary MJO events, the scale decomposition deserves a further examination here. Following Zhao et al. (2013), for each variable \(\varvec{X}\) (denoting \(\varvec{u}\), \(\varvec{v}\), or \(\varvec{q}\)), we make the following decomposition: \(\varvec{X} = \bar{X} + \varvec{X^{\prime}} + \varvec{X}^{*}\). The overbar and the asterisk denote respectively the low-frequency background state (> 90 days) and the high-frequency synoptic scales (< 20 days). In this way, both the zonal and meridional advection can be divided into nine terms. For ease of writing, we use B, M, and H to denote the above three time scales, respectively. Thus, the five linear advections can be abbreviated as BB, MB, HB, BM, and BH, while the four nonlinear advections are MM, HM, MH, and HH. The mathematical meanings of these abbreviations are listed as follows (taking the meridional moisture advection as an example), including the linear advections

and the nonlinear advections

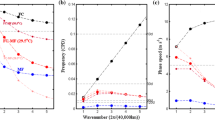

Figure 10 exhibits the vertical profiles of the scale-decomposing advection terms. For the meridional advection (Fig. 10a), we can see that, in the lower troposphere, the moistening effect of linear terms (primarily MB and BM) tends to be more important. Nevertheless, the amplitudes of the nonlinear terms are still comparable with that of the linear terms, especially the HH and HM that are associated with the high-frequency meridional wind anomaly. In the BL, it is interesting to find that the net moistening should be totally determined by the HM and HH. For the zonal advection processes as can be seen from Fig. 10b, except for the MB centered at 500 hPa, all the linear terms play negative feedback in terms of the net moistening effect. In other pressure levels, however, the moistening tendency is totally determined by the nonlinear advections consisting of HH, MM, and HM. To have a quantitative comparison between linear and nonlinear advections, we further represent the column-integrated (200–1000 hPa) budget results shown in Fig. 11, where the linear (nonlinear) results denote the sum of those linear (nonlinear) advections. We can see that the role of nonlinear advections is the most essential, especially the nonlinear meridional advection. The linear meridional advection also plays a role in pre-moistening the column but the contribution of linear zonal advection is negligible.

Same as Fig. 9, but for the scale-decomposed a meridional and b zonal advections, respectively

Column-integrated (200–1000 hPa) budget results of (red) zonal and (blue) meridional advections. “Linear” denotes the sum of all the five linear advections consisting of BB, MB, HB, BM, and BH, whereas “Nonlinear” shows the sum of all the four nonlinear advections, including MM, HM, MH, and HH. Refer to the main text for the physical meanings of these abbreviations

Seen from Fig. 10a, the terms HH and HM, namely the nonlinear moisture advections due to the high-frequency meridional wind anomaly, have large amplitude throughout the lower troposphere. One may wonder what kinds of disturbances are modulating the nonlinear moisture advections. Figure 12 shows the local wavelet analysis (Torrence and Compo 1998) of the column-integrated meridional wind anomaly and the equatorially averaged, 20–90-day, bandpass-filtered OLR anomaly averaged over the MJO initiation location in each case. As seen from this figure, although the initiation time of the large-scale deep convection over the IO is distinctive in different NMRSs, there always exist significant high-frequency signals during the first preceding suppressed phase. The preferred periods cover the quasi 3–4 days (e.g., cases 1 and 4), quasi 4–6 days (e.g., cases 1 and 3), and the quasi 6–8 days (e.g., case 2). Our findings, which have been derived from the CNOP-based methodology, together with the observational studies (e.g., Yasunaga et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2015b; Takasuka et al. 2019) jointly suggest the central importance of the upscale moisture transport associated with the nonlinear moisture advections due to synoptic-scale disturbances in supporting the nonlinear optimal excitation of primary MJO events.

Local wavelet power spectrum of the 20-day, highpass-filtered, vertically integrated, meridional wind anomalies averaged over the MJO initiation location (10°S–5°N, 60–90°E) simulated from a case 1, b case 2, c case 3, and d case 4, respectively. The left axis is the Fourier period (days), whereas the bottom axis is the lead time (days). The dotted area denotes those greater than the 95% confidence level for a red-noise process. The cross-hatched regions on either end indicate the “cone of influence”, where edge effects become important. To facilitate comparison, the time evolutions of domain-averaged, 20-90-day, bandpass-filtered OLR anomalies simulated in different cases are also attached below each subplot

The above scale decomposition has mainly focused on the MJO initiation stage (days − 15 to − 5) and revealed that the nonlinear moisture term plays a crucial role in the moisture advection process, which is in good consistency with the quantitatively observational analysis by Wang et al. (2019a, b). When the CNOP-m triggered deep convection begins to move eastward slowly, however, the linear moisture advection process should become more important. As one can see from the evolution of OLR and wind anomalies shown in the CNOP run in Fig. 7, since day - 5 when the MJO convection was initiated, two cyclonic Rossby wave gyres appear to the west of the moist convection center. The anomalous Rossby wave gyres could enhance the zonal asymmetry of moisture tendency through inducing negative mean moisture advection to the west of the convection (Wang et al. 2018b). These analyses reveal that the different stages of the life cycle of MJO, for example, the initiation and eastward propagation stages should be controlled by distinctive moist processes.

How is the CNOP-type initial moisture perturbation related to the nonlinear upscale moisture transport that excites and maintains the MJO? This may be understood from three aspects. First, the small-amplitude CNOP of moisture may directly evolve into or rectify the high-frequency and intraseasonal anomalies or indirectly lead to the response of high-frequency wind anomaly (refer to Fig. 12, such as quasi-3–4- and quasi-6–8-day meridional wind perturbations), both of which could induce a pre-moistening effect thorough the nonlinear moisture advection terms HH and HM. Second, the CNOP-type initial moisture perturbation may firstly produce small disturbances in the sea-air humidity difference or 10 m wind speed. These initially small disturbances may be amplified enough to influence the intraseasonal surface latent heat flux (see the net effect of CNOP-m on the subgrid-scale condensation, evaporation and eddy transport of moisture in the BL shown in Fig. 9) and therefore to destabilize the MJO through the nonlinear rectification feedback (Zhou and Li 2010; Hsu and Li 2011). Thirdly, the equatorially trapped CNOP-m may firstly evolve into the moist Kelvin wave. The moist Kelvin wave-driven eddy heat and momentum transfer could also induce an upscale impact onto the MJO (Liu and Wang 2013). Under the condition of nonlinearly positive-only precipitation heating combined with the air-sea interaction or the frictionally boundary layer moisture convergence, the multi-wavenumber Kelvin wave may also evolve into the wavenumber-one MJO mode through the planetary-scale selection (Li and Zhou 2009; Wei et al. 2017).

8 Summary and discussions

Despite that the MJO has been detected for almost half a century, our understanding of some of its salient features still remains elusive. For example, we have no idea about how the well-organized, large-scale deep convection-circulation coupling system is excited and whether there exist any significant precursor signals preceding the MJO initiation (Zhang and Yoneyama 2017). This is more so, when it comes to the primary type of MJO events (M08), i.e., those occur as a single event or a first one of a chain of successive events in the real world. Previous studies have shown the critical role of moisture feedback in the MJO dynamics (Raymond and Fuchs 2009; Majda and Stechmann 2009; Sobel and Maloney 2013; Adames and Kim 2016; Liu and Wang 2017), and the composite life cycle of successive MJO events even displays evident pre-moistening signals during the initiation stage (M08). Does this still hold for the primary events? Using a hybrid CGCM that has a good fidelity in simulating the tropical intraseasonal oscillation, in this study, from the nonlinear point of view, we have developed a new CNOP-based methodological framework to investigate the nonlinear excitation of primary MJO events through the identification of optimal moist precursors.

In developing this new framework, we firstly selected several NMRSs and the MJO initiation was then quantitatively defined based on an energy-based metric using a short time-duration space-time spectrum of convection and circulation. Secondly, we constructed a nonlinear optimization problem with a pre-assumption of moisture exciting primary MJO events. Finally, a combined space reduction-DE solving technique is utilized to obtain the optimal solutions, that is, CNOP-m.

A series of numerical experiments associated with the CNOP-m have been carried out. In particular, the simulations with the optimal perturbations have been evaluated against the control and random perturbations simulations. The mean of the optimal perturbations favored moistening of the equatorial region, while in some individual cases, the perturbation also manifested as drying towards the pole. W19 have shown that in observations, slightly less than half of the primary MJO events are preceded by low-tropospheric moistening that originates in the equatorial IO, and the three-dimensional structure of these pre-moistening anomalies bear a strong resemblance with that of CNOP-m. In this study using the output of CGCM, we also proved that 85% of the primary MJO events occurring during boreal winter have similar moist precursor signals as one to three of the four CNOPs. In particular, CNOP3 is the most representative optimal perturbations that can explain 60% of the total primary events. Both the CNOP2 and CNOP4 can explain 40% of the total primary events. CNOP1, however, only explain a small proportion of 10%. The comparisons with both observations and CGCM give credibility to the existence of moisture signals several weeks prior to some primary MJO events. The simulations with optimal precursor moisture perturbations show excitation of strong MJO events whereas the random perturbation simulations do not. These results are valuable in that they support the importance of moisture perturbations characterized by a particular pattern, particularly at a low level, to the nonlinear growth and propagation of the primary MJO events.

The moisture budget analysis revealed that horizontal advections, especially the nonlinear moisture advections by the high-frequency wind disturbances, serves as the dominant physical processes that control the nonlinear optimal excitation of primary MJO events. A wavelet analysis suggested the critical role of the upscale moisture transport associated with the synoptic-scale disturbances, such as the quasi-3–4- and quasi-6–8-day oscillations, in modulating the nonlinear advections. The subgrid-scale processes, including the evaporation, condensation and eddy transport of moisture associated with congestus, was also demonstrated to be important in supporting the net moistening in the BL.

The strong dependence of primary MJO initiation on the nonlinear advections may imply the essence of nonlinearity in controlling the fastest growth of initial perturbations at the subseasonal time scale. To give a clear proof of this implication, we can define an operator \({\boldsymbol{\mathcal{N}}}_{\tau }\) as:

The nonlinearity of \(\boldsymbol{\mathbf{\mathcal{N}}}_{\tau }\) can be proved indirectly by the following criterion, that is, there exists a real number \(\gamma\) (\(\ne 0\)) such that

in which \(\boldsymbol{\mathbf{\mathcal{N}}}_{\tau } \left( {\gamma \varvec{q}_{0\alpha } } \right)\) just characterizes the nonlinear evolution of initial perturbation \(\gamma \varvec{q}_{0\alpha }\), whereas \(\gamma \boldsymbol{\mathbf{\mathcal{N}}}_{\tau } \left( {\varvec{q}_{0\alpha } } \right)\) is its linear counterpart. To get a robust result, six values of \(\gamma\) have been used here, that is, \(\gamma \in \left\{ {0.1, 0.4, 0.8, 1.2, 1.6, 2.0} \right\}\). Figure 13 shows the time evolution of the CNOP-m \(\varvec{q}_{0\alpha }\) in different NMRSs at the forecast time \(\tau\) ranging from days 1 to day 30. We can see that the quasi-linearity only occurs during the first 10 days (Fig. 13a), after that, the nonlinear evolution of CNOP-m is always larger than the linear one (Fig. 13b). This highlights the central importance and necessity of using nonlinear methods to perform the S2S prediction. Besides, we find that the quasi-linearity only appears for a relatively small initial constraint, i.e., \(\gamma < 0.8\). For the large initial constraint of \(\gamma\), the nonlinear evolution is always dominated for both the short-duration and long-duration evolutions. This highlights that the quasi-linear approximation is suitable if and only if the initial constraint is sufficiently small and the forecast time is not long, which has been previously revealed in the predictability study of ENSO (e.g., Mu et al. 2003). This point also serves as an essential difference with the theory of linear singular vector, which is independent of the initial constraint and optimization time (e.g., Mu 2000). In the future study, we will further explore the sensitivity of CNOP-m to the variations of initial constraint \(\gamma\) and optimization time.

a Nonlinearly evolutions (x-axis, g/kg) of the CNOP-type initial perturbations as a function of its linear evolutions (y-axis, g/kg). The quasi-linearity meets when the dots are on and near the solid diagonal. The different colors denote different value of the initial constraint \(\gamma\) used to perform the numerical experiments, in which the gray dots are for the initial constraint \(\gamma\) of 0.1, the red dots are for \(\gamma\) of 0.4, the green dots are for \(\gamma\) of 0.8, the blue dots are for \(\gamma\) of 1.2, the magenta dots are for \(\gamma\) of 1.6, and the cyan dots are for \(\gamma\) of 2.0. b is the same as (a), but for the results of day 11 to day 30

Compared with the random perturbations, the CNOP-m display a much faster growth and trigger the nonlinear excitation of primary MJO events (Fig. 6). This may imply that when we utilize such growing, CNOP-type, initial perturbations to construct the ensemble samples, the skill of the ensemble forecasting associated with the MJO is very likely improved. Benefit from the CNOP-type initial perturbations, we may shed light on the fast-growing initial errors associated with the MJO prediction, as previous studies have shown the similarity between CNOP-type precursors and initial errors in terms of the same reference state (e.g., Mu et al. 2014). Because different NMRSs have produced distinctively CNOP-type optimal precursors (Fig. 3) and thus different fastest growing initial errors, it highlights the necessity of adaptive observations (Palmer et al. 1998) in terms of the MJO, especially over the tropical IO where the lack of in situ data makes such studies difficult, if possible. The robustness of these plausible conjectures, however, needs a substantial number of substantive modeling experiments, which are the key to our future works.

Some caveats also worth being noted when one citing our results or comparing them with other works. In this study, for example, we have only chosen one model to perform our study. The CNOP, however, may display some degree of sensitivity to the model specified (Mu and Duan 2005; Mu et al. 2015). It is, therefore, necessary to examine the optimal excitation of MJO events using multimodel experiments in the future. Under the conditions of limited computational resources and as a first step to recognize the nature of the scientific questions, only four pre-chosen NMRSs have been examined here. To reveal the nature of nonlinear optimal excitation of primary MJO events, more case studies are urgently necessary, and we are devoting to it. During calculating the CNOP-m, we have utilized an EOF-based strategy to reduce the dimensionality of the model as well as the optimization problem. However, if conditions permit, the perfectly accurate optimal precursors should be obtained using more EOF modes or directly the raw total fields. Meanwhile, it will need more advanced computational resources and take more computing time. In the real world, the nonlinear initiation of one primary MJO events may be jointly excited by some combination modes of the possible precursor signals. For example, some studies have suggested the crucial roles of the zonal wavenumber-1 surface pressure anomalies (e.g., Ling et al. 2013), the lower-level easterly wind anomalies (e.g., Straub 2013; Ling et al. 2013), the middle tropospheric cold temperature anomaly (e.g., Matthews 2008; Ling et al. 2013; Yong and Mao 2016), the dynamical vorticity anomalies (e.g., Seo and Song 2012; Zhang and Ling 2012), and even the oceanic dynamical signals associated with the dowelling Rossby waves (e.g., Webber et al. 2010, 2012) in helping exciting the primary MJO events. All of them, however, need more in-depth investigations. In this scenario, the CNOP method (Mu et al. 2010) is still a useful tool to search for these nonlinear optimal combination modes.

References

Adames ÁF (2017) Precipitation budget of the Madden–Julian oscillation. J Atmos Sci 74:1799–1817

Adames ÁF, Kim D (2016) The MJO as a dispersive, convectively coupled moisture wave: theory and observations. J Atmos Sci 73:913–941

Adames ÁF, Patoux J, Foster RC (2014) The contribution of extratropical waves to the MJO wind field. J Atmos Sci 71:155–176

Adames ÁF, Wallace JM, Monteiro JM (2016) Seasonality of the structure and propagation characteristics of the MJO. J Atmos Sci 73:3511–3526

Ahn M et al (2017) MJO simulation in CMIP5 climate models: MJO skill metrics and process-oriented diagnosis. Clim Dyn 49:4023–4045

Baranowski DB, Flatau MK, Flatau PJ et al (2017) Multiple and spin off initiation of atmospheric convectively coupled Kelvin waves. Clim Dynam 49:2991–3009

Benedict J, Randall D (2007) Observed characteristics of the MJO relative to maximum rainfall. J Atmos Sci 64:2332–2354

Birgin EG, Martínez JM, Raydan M (2000) Nonmonotone spectral projected gradient methods on convex sets. SIAM J Optim 10:1196–1211

Bladé I, Hartmann D (1993) Tropical intraseasonal oscillations in a simple nonlinear model. J Atmos Sci 50:2922–2939

Buizza R, Palmer T (1995) The singular-vector structure of the atmospheric global circulation. J Atmos Sci 52:1434–1456

Chen G, Wang B (2018a) Effects of enhanced front walker cell on the eastward propagation of the MJO. J Clim 31:7719–7738

Chen G, Wang B (2018b) Does the MJO have a westward group velocity? J Clim 31:2435–2443

Chen L, Duan W, Xu H (2015a) A SVD-based ensemble projection algorithm for calculating conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation. Sci China Earth Sci 58:385–394

Chen S et al (2015b) A study of CINDY/DYNAMO MJO suppressed phase. J Atmos Sci 72:3755–3779

Ciesielski PE, Johnson RH, Schubert WH, Ruppert JH Jr (2018) Diurnal cycle of the ITCZ in DYNAMO. J Clim 31:4543–4562

DeMott CA, Klingaman NP, Woolnough SJ (2015) Atmosphere-ocean coupled processes in the Madden-Julian oscillation. Rev Geophys 53:1099–1154

Diaconescu E, Laprise R (2012) Singular vectors in atmospheric sciences: a review. Earth-Sci Rev 113:161–175

Duan W, Mu M (2009) Conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation: applications to stability, sensitivity, and predictability. Science China 52:883–906

Feng J, Li T (2016) Initiation mechanisms for a successive MJO event and a primary MJO event during boreal winter of 2000–2001. J Trop Meteorol 22(4):479–496

Fouquart Y, Bonnel B (1980) Computations of solar heating of the earth’s atmosphere- A new parameterization. Beitraege zur Physik der Atmosphere 53:35–62

Fu JX, Wang B (2001) A coupled modeling study of the seasonal cycle of the Pacific cold tongue. Part I: simulation and sensitivity experiments. J Climate 14:765–779

Fu JX, Wang B (2004) The boreal-summer intraseasonal oscillations simulated in a hybrid coupled atmosphere-ocean model. Mon Weather Rev 132:2628–2649

Fu JX, Wang B, Li T (2002) Impacts of air-sea coupling on the simulation of mean Asian summer monsoon in the ECHAM4 model. Mon Weather Rev 130:2889–2904

Fu JX, Wang B, Li T, McCreary J (2003) Coupling between northward propagating ISO and SST in the Indian Ocean. J Atmos Sci 60:1733–1753

Fu JX et al (2015) Distinctive roles of air–sea coupling on different MJO events: a new perspective revealed from the DYNAMO/CINDY field campaign. Mon Weather Rev 143:794–812

Fu JX, Wang W, Ren H-L, Jia X, Shinoda T (2018) Three different downstream fates of the boreal-summer MJOs on their passages over the Maritime Continent. Clim Dyn 51:1841–1862