Abstract

Previous studies show that the dominant mode of variability in the Northeastern subtropical Pacific and Atlantic are analogous. Most attention has been given to the wind-evaporation-sea surface temperature (WES) feedback, but more recent studies suggest that clouds and ocean play a role. Here, it is shown that, while the mode of variability is similar, the quantitative role of clouds and ocean are different. Using Community Earth System Model, version 1.2, cloud feedbacks and interactive ocean dynamics are disabled separately to diagnose the relative contributions of each to sea surface temperature (SST) variability in subtropical northeastern ocean basins. Results from four experiments show that the relative contributions from WES and cloud radiative feedback depend on the role of the ocean. Positive cloud radiative feedback is evident in both basins but has less impact on SST variance in the Atlantic than in the Pacific. The reason for this is that ocean processes strongly damp SST anomalies in the Pacific and weakly enhance SST anomalies in the Atlantic. When cloud feedbacks are disabled, ocean processes become a larger driver of SST variability in the Atlantic. In line with previous studies, the Northeast Pacific SST variability may be understood as a white-noise-forced linear stochastic system with positive feedback from cloud and damping by latent heat flux and ocean processes, while Atlantic SST is driven partially by variations in ocean circulation and requires vertical mixing for rendition. Between these two regions, different ocean dynamics lead to different roles for atmospheric feedbacks but still result in similar patterns of SST variability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Sea surface temperature (SST) variability in northeastern subtropical ocean basins is important for tropical-extratropical teleconnections (Chiang and Vimont 2004; Zhang et al. 2014), low-frequency modes of climate variability (Middlemas and Clement 2016; Di Lorenzo et al. 2015; Di Lorenzo and Mantua 2016), and precipitation on continental coasts (Nobre and Shukla 1996; Kutzbach and Liu 1997; Burgman et al. 2017). A notable example of observed SST variations in this region was the marine heatwave occurring in 2013 through 2015 off the coast of Baja California which led to severe drought conditions in the Western United States (Bond et al. 2015; Seager et al. 2015; Swain et al. 2016). Despite the importance of SST variability in this region, uncertainty about the mechanisms controlling this variability remains.

SST variability on interannual timescales occurring in Northeast ocean basins often resembles a form of tropical-extratropical variability called meridional modes—a mode of variability which is fairly well-understood. Meridional modes occur both in the Atlantic and the Pacific through a combination of trade wind forcing and the wind-evaporation-SST (WES) feedback and are thought to occur through similar mechanisms between the two ocean basins (see Figure 1 in Chiang and Vimont 2004; Xie and Philander 1994). Meridional modes in these two regions are thought to be analogous given their interaction with the ITCZ and their colocation with oceanic upwelling (Xie and Philander 1994; Chiang and Vimont 2004). Recent studies show that this meridional-mode-like SST variability is influenced by positive cloud radiative feedback, which enhances the persistence of SST variability (Smirnov and Vimont 2012; Evan et al. 2013; Bellomo et al. 2014b, 2015; Zhang et al. 2014; de Szoeke et al. 2016). Previous studies also implicitly assume that local anomalous ocean heat transport is not essential for the WES feedback because it occurs in model configurations that do not have interactive ocean dynamics (Chiang and Vimont 2004; Vimont 2010; Smirnov and Vimont 2012). On the other hand, analyses of Atlantic Meridional Mode events in observations suggests that both WES feedback and mixed layer dynamics contribute (Foltz et al. 2012; Rugg et al. 2016). Additionally, Myers et al. (2018b) used satellite observations and assimilated ocean data to deduce that weaker-than-average vertical mixing due to weakened trade winds in combination with anomalously low cloud cover produced SST anomalies associated with the 2013–2015 marine heatwave off the coast of Baja California. Using various model configurations with one climate model, we explore the extent to which that cloud radiative feedback, latent heat flux, and ocean dynamics produce northeastern subtropical SST variability in both Pacific and Atlantic basins on interannual-and-longer timescales.

Positive shortwave cloud radiative feedback on northeast subtropical SST has been identified extensively in observations and models (Klein and Hartmann 1993; Norris and Leovy 1994; Burgman et al. 2008; Clement et al. 2009; Evan et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2014; Bellomo et al. 2014a, b, 2015; de Szoeke et al. 2016; Burgman et al. 2017; Myers et al. 2018a, b), though only one other study has assessed how much subtropical SST variability depends on cloud radiative feedback (Brown et al. 2016). The feedback occurs through climatologically cool SST coinciding with the descending branch of the Hadley circulation, high atmospheric stability, a strong temperature inversion—all of which contribute to the formation of boundary layer stratocumulus cloud decks (Klein and Hartmann 1993; Norris 1998). These low-lying, optically dense clouds reflect incident shortwave radiation, shading the underlying sea surface. Likewise, during periods of anomalously warm SST, the overlying atmosphere is less stable, the cloud fraction decreases, which allows more incident solar radiation to heat the sea surface. A few studies have enhanced the feedback or prescribed cloud forcing in the northeastern subtropical region to find an enhancement of decadal variability (Bellomo et al. 2014a, 2015; Burgman et al. 2017). Bellomo et al. (2014a, 2015) enhanced positive low cloud feedback in the subtropical Pacific Ocean in an atmospheric global climate model (AGCM) coupled to a slab ocean by enhancing the clouds’ optical depth in response to cooling SST. These authors report up to a 100% increase in SST variability on decadal timescales (Bellomo et al. 2014a, 2015). Another study prescribed observed shortwave cloud radiative forcing in a fully-coupled GCM, which reproduced observed decadal variability in Pacific SST and North American precipitation (Burgman et al. 2017). While the findings of these studies highlight the importance of SW cloud radiative feedback for low-frequency variability in SSTs, the methodologies do not isolate how much SST variability depends on cloud radiative feedback. Another study disabled cloud feedbacks entirely to isolate the change in SST variability due to cloud feedback, but these authors were concerned with changes in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation and did not consider the impact of ocean dynamics on cloud radiative feedback (Brown et al. 2016).

The role of ocean dynamics in producing eastern subtropical variability has been given little attention compared to that of WES feedbacks or meridional modes. A couple of Atlantic meridional mode studies find a role for mixed layer depth variations in observations, but these studies focused on the seasonal timescale (Foltz et al. 2012; Rugg et al. 2016). A few other Atlantic meridional mode studies attribute the ocean’s role to variations in gyre circulation (Chang et al. 1997), Ekman transport (Xie 1999), or Ekman pumping (Doi et al. 2010). A more recent study points to Ekman transport as a mechanism for damping SST variance in subtropical ocean basins (Larson et al. 2018). Ultimately, none of these studies provide a role for cloud radiative feedbacks in producing northeastern subtropical SST variability. A study on climate models’ inability to capture SST in Eastern subtropical ocean basins has pointed to both ocean circulation and cloud feedbacks as contributing to SST biases (Zuidema et al. 2016), but those authors focus on biases in the mean state in Southern Hemisphere, while here we are interested in variability.

We use a novel approach to address the role of both ocean dynamics and cloud radiative feedbacks. Comparing meridional-mode-like SST variability in a fully-coupled modeling configuration to that of an AGCM-slab configuration will isolate the role of ocean dynamics while cloud-locking will isolate the role cloud radiative feedbacks. Some studies have noted that atmospheric forcing (Doi et al. 2010) and, in particular, positive cloud feedback (Norris 1998; Myers et al. 2018a) impact the northeast subtropical SST the most during the summertime through shoaling of the mixed layer during this season. This process would be missed in an AGCM coupled to a slab ocean where monthly-varying climatological mixed layer depth is prescribed (Bellomo et al. 2014a, 2015). The competition between cloud feedback and ocean dynamics on SST variability in Northeastern subtropical ocean basins in a climate modeling framework has not been explored in the literature but may offer increased understanding of WES feedback and associated meridional modes, and phenomena like the 2013–2015 NE Pacific heat wave. We attempt to answer two questions in this study: (1) how much does positive cloud radiative feedback matter for SST variability in northeast subtropical ocean basins, and (2) do ocean dynamics change the role of cloud radiative feedbacks?

2 Methods

2.1 Modeling experiments

We compare four climate modeling configurations that are summarized in Table 1: two with no ocean dynamics and two with no cloud radiative feedbacks. We utilize the Community Earth System Model, version 1.2, with the Community Atmosphere Model, version 5 (“CESM1.2”). All have preindustrial control forcing (constant greenhouse gas forcing and aerosol emissions from year 1850). The simulations with active cloud radiative feedbacks are taken from the CESM Large Ensemble Project (Kay et al. 2015). The two experiments with no ocean dynamics use CAM5 coupled to a motionless slab ocean with a spatially-varying but temporally-fixed mixed layer depth (“CAM5-slab”). This model configuration contains no anomalous ocean heat transport; instead, ocean heat transport is prescribed with a climatological “q-flux”. This means that the damping rate of SST variability, or the amount of SST variance, depends solely on the variance of atmospheric fluxes and the heat capacity of the mixed layer. The two experiments using this configuration include one with cloud radiative feedbacks (“control”) and one without (“cloud-locked”).

To disable cloud radiative feedbacks, we utilize the cloud-locking method. Here, cloud fields are prescribed in the radiation module of CAM5 every two hours of the model run to prevent clouds from radiatively interacting with their surroundings. We prescribe the same year of clouds repeatedly so that cloud radiative forcing does not vary on timescales of longer than one year. The results are not sensitive to the year of cloud that is prescribed (not shown). Due to an implementation detail of the cloud-locking methodology, high latitudes have enhanced cloud cover in these experiments that led to a 2K global-average cooling. To bring the CAM5-slab climate back to equilibrium, we add the zonal mean of the initial annual mean TOA imbalance to the climatological q-flux file. This reintroduces whatever energy is lost from the system due to cloud-locking and prevents drift. The length of the cloud-locked CAM5-slab experiment is 370 years. Since these experiments were conducted, the error in the cloud-locking method has been identified and corrected; the q-flux adjustment used here stabilizes the climate appropriately, and we do not anticipate that the results presented here are impacted by this high-latitude effect.

We also conduct a cloud-locking experiment in the fully-coupled CESM1.2 simulations. We repeat the cloud-locking method described above in CESM1.2, except that the experiment length is 315 years, and the climatological SST change is small in the subtropical eastern ocean basins, so no flux adjustment is required. On the other hand, the El Niño Southern Oscillation responds dramatically to cloud-locking by a threefold magnitude increase and a shift to decadal timescales (Middlemas et al. 2019), which dominates the global SST response. Because we are interested in the local energy budget determining SST variability in the subtropical eastern ocean basins, we remove teleconnections from El Niño Southern Oscillation in the fully-coupled simulation by subtracting the Niño3.4 index from every field through linear regression analysis (Chiang and Vimont 2004).

2.2 Isolating SST variability affected by cloud feedback on interannual-and-longer timescales

We are concerned with the impact of positive cloud radiative feedback on SST variability on interannual-and-longer timescales in northeastern subtropical regions, and how ocean dynamics may change that impact. We calculate the shortwave cloud radiative feedback in the control simulations as the pointwise regression of surface shortwave cloud forcing on local SST anomalies (black or gray contours in Figs. 1, 2, 6). We focus on SST in regions that fall within two-thirds of the maximum shortwave positive cloud feedback in CESM1.2 (boxes are identical for CAM5-slab simulation). The resulting box boundaries are from 15N to 28N and 120W to 136.25W in the Pacific, and 10N to 24N and 36.25W to 21.25W in the Atlantic (see black contours and magenta boxes in Fig. 1, as well as black dashed boxes in Figs. 2, 4, 6). Furthermore, previous studies show that the SSTA averaged within these regions appropriately resemble meridional modes (Chiang and Vimont 2004; Zhang et al. 2014). Following Zhang et al. (2014), we low-pass filter every field using a Lanczos filter with 1.5-year cutoff to isolate low-frequency variability. There is no clear pattern in seasonality among the events that we find across the four model configurations, which suggests that the mechanisms we will investigate are independent of the season.

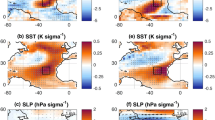

Percent change SST variance (% K K−1) due to cloud-locking in CAM5-slab (top) and fully-coupled CESM1.2 (bottom) in colored contours, and shortwave cloud radiative feedback overlaid in black contours (W m−2 K−1). Shortwave cloud radiative feedback is calculated as the pointwise regression of surface shortwave cloud forcing onto local SST anomalies from the control simulations. Regions that fall within 75% of maximum shortwave cloud radiative feedback are outlined in magenta and are the regions over which energy budgets are calculated in Sects. 4–7. The average percent change in variance in either of these boxes are indicated in text above each panel

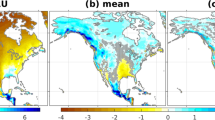

Lag-zero regression of various quantities on standardized SST averaged over region of maximum positive cloud feedback (black dashed boxes; described in Sect. 2.2). Associated surface winds are shown in vectors and only those exceeding 0.5 × standard deviation are pictured. Dark gray contours are total cloud radiative forcing (QCLOUD) regressed on standardized SST, i.e., cloud radiative forcing change per σSST, pictured from − 6 to 6 W m−2 K−1, and in increments of 0.6 W m−2 K−1. Positive values, indicated by solid black contours, are defined as positive down. Magenta contours indicate sea level pressure anomalies per σSST, with levels from − 1.95 to 1.95 hPa K−1 in increments of 4.3 hPa K−1

2.3 Ocean mixed layer heat budget

To understand contributions to SST variability in the Northeastern subtropical ocean basins, we frame our analysis in terms of the ocean mixed layer heat budget, which may be written

where \(\rho\) is the density of seawater (1.025e3 kg m−2), and Cp is the specific heat of seawater, of 3850 J kg−1 K−1. QATM represents the fluxes into the mixed layer from the atmosphere, and include net shortwave radiation (SW), net longwave radiation (LW), latent heat (LHFLX), and sensible heat (SHFLX) fluxes, all defined as positive down or into the surface (2). SW and LW components may be further divided into clearsky and cloudy parts. QOCEAN is the convergence of heat into the oceanic mixed layer by horizontal advection of temperature (first term on the right-hand side of Eq. (3)) and vertical mixing of heat into the bottom of the mixed layer (second term on right hand side). In the horizontal advection term, \(\vec{U}\) is horizontal velocity (U, V) of ocean currents and \(\nabla T\) is the horizontal gradient in mixed layer temperature. Both of these quantities are averaged down to the mixed layer depth at every model output timestep and grid point prior to computation.

The CAM5-slab configuration has a mixed layer depth fixed to the annual mean (\(\bar{H}\)), and there is no ocean heat transport except for a climatological “q-flux” term (Bitz et al. 2012). Since we are only considering anomalous fields and timescales of 1.5 years or longer, this q-flux term should not contribute to the SST variance changes we are concerned with. Thus, we may think of the CAM5-slab heat budget as Eq. (1) with \(Q_{OCEAN} = 0\):

Generally, the surface temperature reflects the convergence of heat in the mixed layer, which is determined by the balance between atmospheric and oceanic fluxes into the mixed layer and the heat capacity of the mixed layer (Eq. 1), but in the CAM5-slab configuration, SST changes in this configuration are determined explicitly by atmospheric heat fluxes into the surface. In this study, we will be considering the anomalies of the heat flux terms, i.e., the seasonal cycle and the mean have been removed from all terms.

3 Changes in SST variance due to cloud-locking with and without ocean dynamics

Cloud radiative feedbacks enhance SST variance in the NE subtropical ocean basins in both the AGCM-slab and fully coupled configurations, but the fully-coupled simulation shows less enhanced SST variance (Fig. 1), suggesting that interactive ocean dynamics alter the influence of cloud radiative feedback in SST variability. We quantify the change in SST variability by calculating the percent change in variance (Fig. 1): \(\% \Delta Var_{SST} = \frac{{\Delta Var_{SST} }}{{\overline{{SST'^{2} }}_{CTRL} }}\), where \(\Delta Var_{SST} = \overline{{SST'^{2} }}_{CTRL} - \overline{{SST'^{2} }}_{CLDLCK}\); a positive value indicates that the SST variance in the simulation with active cloud feedbacks is larger. Due to the location of shortwave cloud radiative feedback (indicated by line contours and magenta boxes in Fig. 1), we expect a decrease in variance when cloud radiative feedbacks are disabled via cloud-locking, assuming positive cloud radiative feedback enhances SST variability. Indeed, positive values, indicating that SST variance is larger when cloud radiative feedbacks are active, emerge in regions of large positive cloud radiative feedback (red shaded contours, Fig. 1). Both model configurations and regions exhibit analogous patterns of SST variance change that resemble the SST signal associated with meridional modes in response to disabling cloud radiative feedbacks (Fig. 1). This is consistent with Evan et al.’s (2013) result that positive shortwave stratocumulus cloud feedback in the Atlantic enhances the persistence of SST anomalies which play a role in meridional modes. In the region defined by the magenta box in the AGCM-slab configuration (Fig. 1), SST variance is enhanced by cloud radiative feedbacks by ~ 42% in the NE Pacific and ~ 37% in the NE Atlantic. When interactive ocean dynamics are allowed to impact SST, SST variability of the Atlantic responds differently from the Pacific. The fully-coupled simulation shows that cloud radiative feedbacks enhance SST variance by ~ 35% in the Pacific and ~ 13% in the Atlantic. This leaves two questions: (1) why do clouds impact SST variance more in a model configuration without interactive ocean dynamics, and (2) why do clouds impact SST variance less in the NE Atlantic than in the Pacific in the configuration with interactive ocean dynamics?

4 The NE Pacific

We start by investigating the response of latent heat flux feedback, or WES feedback, to disabling cloud radiative feedbacks in the NE Pacific. Figure 2 shows the lag-0 regression of various heat budget terms on standardized SST anomalies averaged in the area of maximum shortwave cloud feedback described in Sect. 2.2 (and outlined in the black dashed box on Fig. 2). This regression highlights the contribution of each term to one standard deviation of SST anomaly. Dark gray contours nearly disappear in the Fig. 2c, d because climatological cloud fields are prescribed in the cloud-locked simulations, and so cloud radiative forcing does not vary on timescales longer than one year by design. Bottom panels (“a minus c” and “b minus d”) show that cloud radiative feedbacks enhance SST anomalies in almost the entire northeastern Pacific. Furthermore, the righthand panels (“b minus a” and “d minus c”) clearly show that anomalous ocean heat transport damps maximum SST anomalies.

These results are further illustrated by lead-lag regressions of various mixed layer heat budget terms onto SST anomalies averaged over the boxes described in Sect. 2.2 (Fig. 3). The LHS of Eq. (1) is indicated by the dashed black lines, which, in the case of the AGCM-slab configuration (Fig. 3, left panels) must be balanced by atmospheric fluxes (solid red lines). This is indicated by the fact that they are overlaid in the left panels. In both configurations and in the experiments with cloud radiative feedbacks (Fig. 3, top left panel) downward cloud radiative forcing (solid orange lines) becomes more positive as the temperature increases, leading to a positive SST anomaly (solid black lines). This represents the reduced amount of stratocumulus clouds with increasing temperature in positive cloud radiative feedback (Klein and Hartmann 1993; Norris and Leovy 1994; Burgman et al. 2008; Clement et al. 2009; Bellomo et al. 2014b; Myers et al. 2018a, b). Here, cloud radiative forcing includes LW and SW, but they oppose each other: LW acts as a damping and cools the event, albeit less than the amount that SW warms (not pictured). Latent heat flux is also a large contributor to the temperature tendency, especially in the termination of the warm event (solid green lines), representing latent heat flux damping on warmer SST. When cloud radiative feedbacks are disabled (bottom panels, Fig. 3), the cloud radiative forcing goes to near-zero since we prescribe climatological clouds and the terms pictured are low-pass filtered by 1.5 years. The cloud radiative forcing is not exactly zero because the cloud radiative forcing metric contains effects of cloud masking, i.e., both cloud and non-cloud (i.e., water vapor) radiative forcing (Soden et al. 2004). By removing positive cloud radiative feedback, and thus, low-frequency anomalies of cloud radiative forcing, the total atmospheric flux QATM decreases, and latent heat flux contributes more in the cloud-locked simulation than in the control per unit SST anomaly (Fig. 3, compare top and bottom panels). In fact, without cloud radiative feedback, latent heat flux more than doubles per unit SST anomaly and explains nearly all of the atmospheric forcing in the AGCM-slab configuration (Fig. 3, lower left panel). This would be the traditional WES feedback.

Lead-lag regressions of various anomalous mixed layer energy budget terms on SST anomalies within area of maximum positive cloud radiative feedback (i.e., the magenta box pictured in the North Pacific on Fig. 1; described in Sect. 2.2). CAM5-slab is pictured on the left, CESM1.2 on the right. Control (cloud radiative feedbacks active) simulations are in the top panels and the cloud-locked (cloud feedbacks disabled) simulations are in the bottom panels

SST variability and its response to disabling cloud radiative feedbacks in the fully-coupled configuration (Fig. 1, bottom panel) is different from the AGCM-slab configuration (Fig. 1, top panel) because ocean heat transport also contributes to the temperature variations. In the case of the NE Pacific, the ocean flux acts to damp SST anomalies (Fig. 3, right panels, solid blue line), indicative of a divergence of heat (negative values) at the peak of SST. The divergence of heat is around − 4 W m−2 K−1 regardless of cloud radiative feedbacks, meaning the ocean flux contribution to SST variability is not affected by cloud radiative feedback. The ocean acts merely as a damping on SST. This is also reflected by the fact that maximum SST in CESM1.2 is weaker than in CAM5-slab configuration (Fig. 2). The role of CESM1.2’s atmospheric feedbacks is just like that of the CAM5-slab configuration: the WES feedback becomes the dominant driver when cloud feedbacks are disabled. Latent heat flux increases by around two times per degree K when cloud radiative feedbacks are disabled (Fig. 3, right panels). In other words, the SST variability of CESM1.2 can be conceptualized by the CAM5-slab plus additional oceanic damping.

The spatial pattern of ocean damping at the peak of SSTA in the North Pacific is illustrated in the left-hand panels of Fig. 4. Oceanic heat flux damping occurs in the North Pacific from west of the North American coast across the basin, though the maximum location of damping occurs slightly south of the maximum SSTA (compare black contours to colored contours in Fig. 4a, c). The structure of ocean damping follows the structure of SSTA, which becomes more zonally symmetric when cloud radiative feedbacks are disabled (compare colored contours in Fig. 4a, c). This is also illustrated by the zonal elongation of the Aleutian Low without cloud radiative feedbacks (compare magenta contours in Fig. 2a, c).

Lag-zero regression of SST and QOCEAN on standardized SST averaged over region of maximum positive cloud feedback (black dashed boxes; described in Sect. 2). Colored contours show the contribution of QOCEAN to SST. The blue contour indicates the zero-crossing of QOCEAN; i.e., from ocean heat flux divergence to convergence, or from damping to enhancing SST. Black contours are SST per σSST and are pictured from − 0.75 to 0.75 K K−1 in increments of 0.075 K K−1

Numerous previous studies have shown that SST in the Northeast Pacific acts like a linearly damped stochastic model driven by atmospheric white noise with feedbacks from entrainment (Deser et al. 2003), clouds (Park et al. 2006), or ENSO (Newman et al. 2003; Di Lorenzo et al. 2015; Newman et al. 2016). Understanding the complex relationships between SST variability, surface heat flux, and ocean heat transport can be tricky (e.g., Cane et al. 2017), so we use a simple stochastic model to construct hypotheses to test against that of the more complex model:

\(\lambda_{LHFLX}\) is the latent heat flux damping feedback, \(N_{LHFLX}\) is the white noise component of latent heat flux caused by high frequency wind fluctuations, \(\lambda_{CLOUD}\) is the positive cloud radiative feedback, \(N_{CLOUD}\) is the white noise component of cloud forcing related to perturbations unrelated to SST, and \(\gamma_{OCEAN}\) is ocean damping. In this case, all damping rates are calculated using the fully-coupled control experiment for latent heat flux, cloud forcing, and net ocean flux following Park et al. (2005), i.e., as the ratio of lagged covariance between SST and each flux over the lagged autocovariance of SST (see their equation (1)). Then, one or more damping rates are set to zero to simulate our experimental model configurations. Specifically, to simulate the CAM5-slab configuration, we set ocean damping to zero, and the cloud-locking experiments are simulated by setting the cloud feedback term and associated noise to zero. All other damping rates are that of the fully-coupled control simulation.

The roles of cloud radiative feedback and latent heat flux feedback in producing SST variability are the same among CAM5-slab, CESM1.2, and the stochastic model: both cloud radiative feedback and latent heat flux forcing contribute to the onset of warm SST. Without cloud radiative feedbacks, latent heat flux doubles per unit change in SSTA (compare solid green lines between top panels and bottom panels in Fig. 5). Ocean damping stays approximately the same with or without cloud radiative feedbacks (Fig. 5, right panels, solid blue lines).

Lead-lag regression of various mixed layer energy budget terms computed with a white-noise-forced linear stochastic model. Feedback values used in the stochastic model are derived from the corresponding model configuration in the Northeast Pacific. The model without ocean damping is pictured on the left, with ocean damping on the right. The model with cloud feedback is pictured in the top panels and that with cloud feedback set to zero are in the bottom panels. See Sect. 4 for a description of the model formulation

The major differences between the representation of NE Pacific SST in the climate model and the stochastic model is that latent heat flux and ocean heat convergence are larger contributors to SST anomalies in the stochastic model (compare left panels of Figs. 3 and 5) but only because other potentially competing flux terms are not included in the stochastic model. Despite these differences, we are able to capture the dominant feedbacks on SST. In fact, the change in the “slab” due to setting cloud feedback equal to zero in the stochastic model is greater than that of the “fully-coupled”; SST variance is reduced by 35.9% with cloud-locking in the “slab” and 28.3% in the “fully-coupled”. This is similar to the relationship found between the cloud-locked CAM5-slab and CESM1.2, where the change in variance is approximately 42% and 35%, respectively. It is also important to note that, just like the more complex model, ocean damping results in a smaller response due to cloud-locking, or smaller SST anomalies (Figs. 2b, d, 4a, c). The stochastic model can reproduce the relationship between SST variance, positive cloud radiative feedback, and latent heat flux and oceanic damping found in the comprehensive climate model.

It should be noted that the ocean damping interannual warming events presented here is different than the role of the ocean during the 2013–2015 marine heatwave discussed in Myers et al. (2018b). Those authors presented observations that are consistent with weaker trade winds, which the authors presume suppress oceanic upwelling, both of which enhance mixed layer warming. We will show in Sect. 6 that vertical mixing actually dominates the ocean damping evident on interannual timescales in the Northeast Pacific in CESM1.2.

5 The NE Atlantic

The response of the WES feedback and large-scale atmospheric circulation to disabling either cloud radiative feedbacks or interactive ocean heat dynamics is similar between the NE Atlantic basin and NE Pacific basin. Figure 6 shows the SSTA and atmospheric response to disabling either by regressing various fields onto standardized SSTA. Again, contribution from cloud radiative forcing disappears with cloud-locking, weakening the maximum value of SSTA in the northeastern ocean basin in CAM5-slab (panel “a minus c” in Fig. 6). Cloud radiative forcing produces larger zonal asymmetry in SSTA in the CAM5-slab configuration, so when cloud radiative feedbacks are disabled, more zonally-symmetric SST anomalies appear (bottom two left panels of Fig. 6). Atmospheric circulation follows (magenta contours, left panels of Fig. 6). On the other hand, ocean coupling slightly changes the response of SST and associated atmospheric circulation to disabling cloud feedbacks (middle vertical panels of Fig. 6). Furthermore, cloud feedbacks affect the temperature response to ocean coupling (compare “b minus a” and “d minus c” on Fig. 6). With cloud feedbacks, ocean coupling weakens the zonal gradient in SST anomalies set up by cloud feedbacks (top panels, Fig. 6). Without cloud feedbacks, ocean coupling shows a smaller impact on SST anomalies (“d minus c”, Fig. 6).

Same as Fig. 2 but for the Northeast Atlantic

We investigate this balance between cloud feedbacks and ocean coupling further with a surface energy budget within the region of maximum positive cloud feedback defined in Sect. 2. Without ocean dynamics and cloud radiative feedbacks in CAM5-slab, latent heat flux increases per unit SSTA (Fig. 7, left panels, green lines), consistent with the NE Pacific, suggesting that the contribution of the WES feedback to SSTA increases without cloud radiative feedbacks. In the fully-coupled cloud-locked simulation, however, latent heat flux contribution per unit SSTA decreases relative to the fully-coupled control simulation without cloud radiative feedbacks (Fig. 7, right panels, green lines). The balance of ocean and atmospheric fluxes becomes smaller. The weak damping by ocean coupling observed in the presence of cloud feedbacks changes to weak enhancement as the warm event subsides (compare blue lines on right panels of Fig. 7), suggesting that ocean dynamics are important for the simulation of SST variability. This reveals that ocean heat transport has the potential to drive SST anomalies rather than damp them like in the NE Pacific or stochastic model. This is illustrated further by the right-hand panels of Fig. 4. A small region of ocean damping is co-located with maximum shortwave cloud feedback (black dashed box) when cloud radiative feedbacks are active (Fig. 4, top right panel, blue colored contours). When cloud radiative feedbacks are disabled, the weak damping confined to the small area of the maximum positive cloud feedback moves westward and is partially replaced by increased coastal ocean heat convergence (Fig. 4, bottom panel, colored contours). This implies that, unlike the Pacific, where the same underlying stochastic model can explain all four model configurations (by simply turning ‘on’ and ‘off’ ocean damping and clouds), in the Atlantic, the underlying ‘model’ would change depending on which processes are enabled/disabled.

Same as Fig. 3 but for the Northeast Atlantic

6 Drivers of ocean heat convergence and divergence

In the Atlantic, weak ocean heat divergence provides a weak damping during maximum SSTA, but when cloud radiative feedbacks are disabled, weak ocean heat convergence occurs during the abatement of SSTA occurring on timescales longer than 1 year (Figs. 6, 7). Meanwhile, ocean heat divergence damps SSTA in the Pacific basin, whether cloud radiative feedbacks are active or not. What oceanic processes may be driving these differences in ocean heat convergence between ocean basins and the changes in ocean contribution due to disabling cloud radiative feedbacks in the Atlantic?

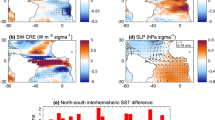

Studies have pointed to a variety of oceanic drivers of SST variability in the subtropical eastern Atlantic, such as horizontal advection of heat by Ekman transport (Xie 1999) and geostrophic currents (Servain et al. 1999) as well as vertical mixing, such as through mixed layer depth variations (Doi et al. 2010; Foltz et al. 2012; Rugg et al. 2016). We separate total oceanic heat flux convergence into horizontal advection and vertical mixing in both locations to shed light on mechanisms of ocean contribution to SST variability (Eq. 3 in Sect. 2). We find that the total oceanic heat flux contribution to SST change is weak in the Atlantic (≅ 1 W m−2 K−1) compared to the Pacific (≅ 4 m−2 K−1), and thus, the subtle balance between horizontal advection and vertical mixing can change whether the ocean is damping or enhancing SST anomalies (Fig. 8). When cloud radiative feedbacks are active, both vertical mixing (magenta lines, Fig. 8) and horizontal advection (light green lines, Fig. 8) act to cool the mixed layer at the peak of SST anomalies and weakly enhances SST during the termination of positive SST anomalies (top right panel, Fig. 8). When cloud feedbacks are disabled, horizontal advection counteracts the positive contribution from vertical mixing to result in a nearly negligible role from oceanic heat flux convergence at the peak of SST anomalies, but then enhances positive SST anomalies at the peak of the event (bottom right panel, Fig. 8).

Lead-lag regressions of various anomalous oceanic terms in the mixed layer energy budget on SST anomalies within regions of maximum positive cloud feedback (described in Sect. 2.2) in the subtropical Northeast Pacific (left) and Atlantic (right). Control (cloud radiative feedbacks active) simulations are in the top panels and the cloud-locked (cloud feedbacks disabled) simulations are in the bottom panels

In the North Pacific, the largest contributor to total oceanic heat transport is vertical mixing (Fig. 8). Vertical mixing has been hypothesized to drive North Pacific SST variations through entrainment (Alexander et al. 1999; Deser et al. 2003; Park et al. 2006) and Ekman pumping (Doi et al. 2010). In CESM1.2, vertical mixing plays the same role whether or not cloud feedbacks are active (left panels of Fig. 8). Though we do not find seasonality in the occurrence of interannual warm events in either Atlantic or Pacific basins, we cannot rule out that the damping (at least in winter months) in the Pacific basin is due to entrainment, possibly through the re-emergence of cold water from the prior boreal winter via the “re-emergence mechanism” (Alexander et al. 1999; Deser et al. 2003; Park et al. 2006). Damping in other seasons could be due to the mixed layer deepening when SSTs are warm, mixing cold water from below into the mixed layer—and heat flux changes by changes in the mixed layer are not explicitly calculated in the present analysis.

The differences in oceanic contributions to SST variability between the Northeastern subtropical ocean basins may be due to the size and scale of the ocean circulation patterns within each basin. The spatial pattern of total oceanic heat flux contribution in both Atlantic and Pacific basins shows that the oceanic contribution in the Pacific basin is more coherent and larger in both magnitude and area than that of the Atlantic (Fig. 4, compare left and right panels). We hypothesize that the ocean circulation in the North Pacific is less sensitive to atmospheric perturbations like that imposed by cloud-locking due to its large spatial scale. Thus, the ocean’s role in SST variability in the Pacific is the same with and without cloud radiative feedbacks. In the Atlantic, on the other hand, oceanic contributions to SST variability are small in magnitude and noisy in space (Fig. 4, right panels, blue contours). Here, the atmospheric circulation may more easily change the sign of ocean heat flux convergence under the region of maximum cloud radiative feedback, thus altering the impact of cloud feedbacks on SST anomalies.

7 Discussion and conclusions

We find that, while the atmospheric processes producing meridional-mode-like interannual SST variability in the Pacific and Atlantic basins are similar, the respective roles of the ocean are not. Through climate model configurations with cloud radiative feedbacks and ocean dynamics disabled both separately and together, we have shown that the impact of positive cloud radiative feedback on SST variability is determined by the role of ocean dynamics. Clouds enhance variability in both regions, consistent with Evan et al. (2013), but the enhancement is stronger in the Pacific than in the Atlantic. In the NE Pacific, when cloud radiative feedbacks cannot enhance SST variability, WES feedback prevails. The ocean exports heat from the NE Pacific at the peak of an SST event regardless of cloud radiative feedbacks, meaning that the ocean acts as a constant damping. In the Atlantic, on the other hand, WES feedback is active, but contribution from oceanic processes are small. Here, cloud radiative feedback reinforces while the ocean damps SST anomalies. When cloud radiative feedbacks are disabled, the circulation responds so as to change the sign of the Atlantic’s weak oceanic contributions, so the ocean heat transport enhances SST anomalies without cloud radiative feedbacks. This means the change in SST variance due to cloud-locking is reduced relative to that in the North Pacific. The different roles of the ocean in the two basins may be a reason why the observed summertime shortwave feedback in the Atlantic (6.7 ± 2.7 W m−2 K−1) is less than that of the Pacific (9.1 ± 2.4 W m−2 K−1) (Myers et al. 2018a).

This is the first study to simultaneously isolate contributions from cloud feedback and ocean dynamics to Northeastern subtropical SST variability and leaves implications for future study. Though we have only utilized one climate model, CESM-CAM5 produces more realistic stratocumulus cloud feedback than other models (Myers and Norris 2015). The large-scale changes in atmospheric circulation induced by cloud-locking provide motivation for understanding the role of subtropical stratocumulus cloud feedback on modes of variability in Northern ocean basins, like the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO). In fact, some studies have already highlighted the role of positive low-cloud radiative feedback for low-frequency variations in both the Pacific (Clement et al. 2009) and the Atlantic (Bellomo et al. 2015; Myers et al. 2018a). The results presented here raise the possibility of cloud-SST-ocean interactions that warrant further exploration in other climate models and offer some guidance in interpreting observations of this region.

References

Alexander MA, Deser C, Timlin MS (1999) The emergence of SST anomalies in the North Pacific Ocean. J Clim 12:2419–2433. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1999)012%3c2419:trosai%3e2.0.co;2

Bellomo K, Clement A, Mauritsen T et al (2014a) Simulating the role of subtropical stratocumulus clouds in driving Pacific climate variability. J Clim 27:5119–5131. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-13-00548.1

Bellomo K, Clement AC, Norris JR, Soden BJ (2014b) Observational and model estimates of cloud amount feedback over the Indian and Pacific Oceans. J Clim 27:925–940. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-13-00165.1

Bellomo K, Clement AC, Mauritsen T et al (2015) The influence of cloud feedbacks on equatorial Atlantic variability. J Clim 28:2725–2744. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-14-00495.1

Bitz CM, Shell KM, Gent PR et al (2012) Climate sensitivity of the community climate system model, version 4. J Clim 25:3053–3070. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-11-00290.1

Bond NA, Cronin MF, Freeland H, Mantua N (2015) Causes and impacts of the 2014 warm anomaly in the NE Pacific. Geophys Res Lett 42:3414–3420. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015gl063306

Brown PT, Lozier MS, Zhang R, Li W (2016) The necessity of cloud feedback for a basin-scale atlantic multidecadal oscillation. Geophys Res Lett 43:3955–3963. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016gl068303

Burgman RJ, Clement AC, Mitas CM et al (2008) Evidence for atmospheric variability over the Pacific on decadal timescales. Geophys Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007gl031830

Burgman RJ, Kirtman BP, Clement AC, Vazquez H (2017) Model evidence for low-level cloud feedback driving persistent changes in atmospheric circulation and regional hydroclimate. Geophys Res Lett 44:428–437. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016gl071978

Cane MA, Clement AC, Murphy LN, KBellomo (2017) Low-pass filtering, heat flux, and Atlantic multidecadal variability. J Clim 30(18):7529–7553

Chang P, Ji L, Li H (1997) A decadal climate variation in the tropical Atlantic Ocean from thermodynamic air-sea interactions. Nature 385:516–518. https://doi.org/10.1038/385516a0

Chiang JC, Vimont DJ (2004) Analogous Pacific and Atlantic Meridional modes of tropical atmosphere–ocean variability. J Clim 17:4143–4158. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli4953.1

Clement AC, Burgman R, Norris JR (2009) Observational and model evidence for positive low-level cloud feedback. Science 325:460–464. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1171255

de Szoeke SP, Verlinden KL, Yuter SE, Mechem DB (2016) The time scales of variability of marine low clouds. J Clim 29:6463–6481. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-15-0460.1

Deser C, Alexander MA, Timlin MS (2003) Understanding the persistence of sea surface temperature anomalies in midlatitudes. J Clim 16:57–72. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(2003)016%3c0057:utposs%3e2.0.co;2

Di Lorenzo E, Mantua N (2016) Multi-year persistence of the 2014/15 North Pacific marine heatwave. Nat Clim Change 6:1042–1047. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3082

Di Lorenzo E, Liguori G, Schneider N et al (2015) ENSO and meridional modes: a null hypothesis for Pacific climate cariability. Geophys Res Lett 42:9440–9448. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015gl066281

Doi T, Tozuka T, Yamagata T (2010) The Atlantic meridional mode and its coupled variability with the Guinea dome. J Clim 23:455–475. https://doi.org/10.1175/2009jcli3198.1

Evan AT, Allen RJ, Bennartz R, Vimont DJ (2013) The modification of sea surface temperature anomaly linear damping time scales by stratocumulus clouds. J Clim 26:3619–3630. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-12-00370.1

Foltz GR, McPhaden MJ, Lumpkin R (2012) A strong Atlantic Meridional Mode Event in 2009: the role of mixed layer dynamics. J Clim 25:363–380. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-11-00150.1

Kay JE, Deser C, Phillips A et al (2015) The Community Earth System Model (CESM) large ensemble project: a community resource for studying climate change in the presence of internal climate variability. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 96:1333–1349. https://doi.org/10.1175/bams-d-13-00255.1

Klein SA, Hartmann DL (1993) The seasonal cycle of low stratiform clouds. J Clim 6:1587–1606. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1993)006%3c1587:tscols%3e2.0.co;2

Kutzbach KE, Liu Z (1997) Response of the African monsoon to orbital forcing and ocean feedbacks in the middle holocene. Science 278:440–443. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.278.5337.440

Larson SM, Vimont DJ, Clement AC, Kirtman BP (2018) How momentum coupling affects SST variance and large-scale pacific climate variability in CESM. J Clim 31:2927–2944. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-17-0645.1

Middlemas EA, Clement AC (2016) Spatial patterns and frequency of unforced decadal-scale changes in global mean surface temperature in climate models. J Clim 29:6245–6257. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-15-0609.1

Middlemas EA, Clement AC, Medeiros B, Kirtman B (2019) Cloud radiative feedbacks and El Niño Southern Oscillation. J Clim 32:4661–4680. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-18-0842.1

Myers TA, Norris JR (2015) On the relationships between subtropical clouds and meteorology in observations and CMIP3 and CMIP5 models*. J Clim 28(8):2945–2967

Myers TA, Mechoso CR, Cesana GV et al (2018a) Cloud feedback key to marine heatwave off Baja California. Geophys Res Lett 45:4345–4352. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018gl078242

Myers TA, Mechoso CR, DeFlorio MJ (2018b) Coupling between marine boundary layer clouds and summer-to-summer sea surface temperature variability over the North Atlantic and Pacific. Clim Dyn 50:955–969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3651-8

Newman M, Compo GP, Alexander MA (2003) ENSO-forced variability of the Pacific decadal oscillation. J Clim 16:3853–3857. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(2003)016%3c3853:evotpd%3e2.0.co;2

Newman M, Alexander MA, Ault TR et al (2016) The Pacific decadal oscillation, revisited. J Clim 29:4399–4427. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-15-0508.1

Nobre P, Shukla J (1996) Variations of sea surface temperature, wind stress, and rainfall over the tropical Atlantic and South America. J Clim 9:2464–2479. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1996)009%3c2464:vosstw%3e2.0.co;2

Norris JR (1998) Low cloud type over the ocean from surface observations. Part I: relationship to surface meteorology and the vertical distribution of temperature and moisture. J Clim 11:369–382. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1998)011%3c0369:lctoto%3e2.0.co;2

Norris JR, Leovy CB (1994) Interannual variability in stratiform cloudiness and sea surface temperature. J Clim 7:1915–1925. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1994)007%3c1915:ivisca%3e2.0.co;2

Park S, Deser C, Alexander MA (2005) Estimation of the surface heat flux response to sea surface temperature anomalies over the global oceans. J Clim 18:4582–4599. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli3521.1

Park S, Alexander MA, Deser C (2006) The impact of cloud radiative feedback, remote ENSO forcing, and entrainment on the persistence of North Pacific Sea surface temperature anomalies. J Clim 19:6243–6261. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli3957.1

Rugg A, Foltz GR, Perez RC (2016) Role of mixed layer dynamics in tropical north Atlantic interannual sea surface temperature variability. J Clim 29:8083–8101. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-15-0867.1

Seager R, Hoerling M, Schubert S et al (2015) Causes of the 2011–14 California drought. J Clim 28:6997–7024. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-14-00860.1

Servain J, Wainer I, McCreary JP, Dessier A (1999) Relationship between the equatorial and meridional modes of climatic variability in the tropical Atlantic. Geophys Res Lett 26:485–488. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999gl900014

Smirnov D, Vimont DJ (2012) Extratropical forcing of tropical Atlantic variability during boreal summer and fall. J Clim 25:2056–2076. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-11-00104.1

Soden BJ, Broccoli AJ, Hemler RS (2004) On the use of cloud forcing to estimate cloud feedback. J Clim 17:3661–3665. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<3661:OTUOCF>2.0.CO;2

Swain DL, Horton DE, Singh D, Diffenbaugh NS (2016) Trends in atmospheric patterns conducive to seasonal precipitation and temperature extremes in California. Sci Adv 2:e1501344. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501344

Vimont DJ (2010) Transient growth of thermodynamically coupled variations in the tropics under an equatorially symmetric mean state*. J Clim 23(21):5771–5789

Xie S-P (1999) A dynamic ocean–atmosphere model of the tropical Atlantic decadal variability. J Clim 12:64–70. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442-12.1.64

Xie S-P, Philander SGH (1994) A coupled ocean–atmosphere model of relevance to the ITCZ in the eastern Pacific. Tellus A 46:340–350. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0870.1994.t01-1-00001.x

Zhang H, Clement A, Di Nezio P (2014) The South Pacific Meridional Mode: a mechanism for ENSO-like variability. J Clim 27:769–783. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-13-00082.1

Zuidema P, Chang P, Medeiros B, Kirtman BP, Mechoso R, Schneider EK, Toniazzo T, Richter I, Small RJ, Bellomo K, Brandt P, de Szoeke S, Farrar JT, Jung E, Kato S, Li M, Patricola C, Wang Z, Wood R, Xu Z (2016) Challenges and prospects for reducing coupled climate model SST biases in the eastern tropical Atlantic and Pacific Oceans: the U.S. CLIVAR eastern tropical oceans synthesis working group. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 97(12):2305–2328

Acknowledgements

The authors thank T. Myers for insightful discussion throughout the project and guidance in computing the subtropical mixed layer heat budget. We express immense gratitude to J. Olson at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) for his help in writing the module for cloud-locking in CESM. The authors further acknowledge the resources provided by NCAR, namely supercomputing resources on Yellowstone. We extend our thanks to NCAR staff for making the CESM Large Ensemble data publicly available for use in this study. Support was provided by National Science Foundation grants with award numbers 1735245 and 1650209 as well as the Graduate Research Fellowship program. Portions of this study were supported by the Regional and Global Model Analysis (RGMA) component of the Earth and Environmental System Modeling Program of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Biological and Environmental Research (BER) via National Science Foundation IA 1844590.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Middlemas, E., Clement, A. & Medeiros, B. Contributions of atmospheric and oceanic feedbacks to subtropical northeastern sea surface temperature variability. Clim Dyn 53, 6877–6890 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-019-04964-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-019-04964-1