Abstract

The present developments in 10 m wind seasonal forecast products have lead to a growth in the number of studies analysing different aspects of both its predictability and applicability. However, there is still a lack of global studies analysing the statistical properties of the probability distribution of 10 m wind speed comparing the seasonal forecast systems with the widely used reanalysis products. To fill this gap we have studied the properties of the probability distributions of 10 m wind speed from the ERA-Interim reanalysis and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts System 4 seasonal forecast system. We have focused on two seasons, JJA and DJF, considering both their interannual and intraseasonal variability. The 10 m wind speed distribution has been characterized in terms of the four main moments of the probability distribution (mean, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis). We have also computed the coefficient of variation to identify the regions with the higher wind variability and the Shapiro–Wilks goodness of fit test to assess their normality. This set of parameters is important to provide useful climate information in wind energy decision-making processes that use simple assumptions of the wind speed frequency distribution to properly estimate the wind energy potential. Besides, this study also illustrates where the discrepancies of the distributions of the seasonal predictions and the reference dataset are higher and, thus, which might need special attention from a bias adjustment perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Climate change mitigation seeks the progressive substitution of fossil energy sources by cleaner renewable ones (e.g. Edenhofer et al. 2014). In this framework wind-power production is one of the most rapidly evolving fields (e.g. Chen 2011; Higgins and Foley 2013; Firestone et al. 2015). Nevertheless, wind is a variable subject to a strong variability at multiple time scales (Pryor et al. 2006). Thus, the critical effects that the irregularity of calm and gusty periods have on both the wind farms functionality and electricity distribution makes the possibility to foretell wind speed anomalies and engaging research for climate services (Hewitt et al. 2012; Torralba et al. 2017). Nevertheless, while short-term wind speed forecasting is already consolidated (Costa et al. 2008; Zhu and Genton 2012), the use of seasonal forecasts in the operational long range planning is rather limited (Jung and Broadwater 2014).

Moreover, in the framework of seasonal forecast verification it is important to know whether the characteristics of the simulated distribution of a variable are similar to its reference counterpart. This is essential to guide post-processing techniques such as bias correction or statistical downscaling (e.g. Benestad et al. 2008; Ruffault et al. 2013). In this regard the choice of ERA-Interim (ERA-Int; Dee et al. 2011) is a great opportunity to analyse the distribution’s characteristics of a dataset that has been extensively used in a wide range of research fields such as climatology (e.g. Škerlak et al. 2014), climate change (e.g. Andres et al. 2014), characterization of extremes (e.g. Cornes and Jones 2013), etc. More specifically, concerning wind-power forecasting, production and verification, it has been thoroughly applied also with positive results (e.g. Kiss et al. 2009; Rose and Apt 2015; Lorenz and Barstad 2016).

Concerning the seasonal forecast system, we have selected the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasting System 4 (S4; Molteni et al. 2011) which is the evolution of the well-considered ECMWF System 3 (Stockdale et al. 2011) and its full potential is still being unfolded (e.g. Tompkins and di Giuseppe 2015; Marcos et al. 2015; Ogutu et al. 2016; Marcos et al. 2017; Torralba et al. 2017). Nevertheless, there are still great uncertainties on the results obtained by seasonal forecast systems (Parker 2016), due to atmospheric and oceanic uncertainty along with the need for several parametrization and computational approximations during calculations (Palmer et al. 2005; Delsole and Shukla 2010). This makes post-processing methods such as bias correction and downscaling necessary for end-user applications. But these methodologies need a thorough knowledge of the inner properties of the variable distributions depicted both by the seasonal forecast systems and the reference datasets (e.g. Amengual et al. 2012).

Consequently, this paper tries to fill the existing gap in the characterization of the probability distribution of 10 m wind speed at a global scale by discussing and comparing the most relevant features of this variable in DJF (December–January–February) and JJA (June–July–August) for both S4 and ERA-Int datasets. Those seasons are the most important for stakeholders because they hold the greatest potential regarding seasonal predictability and wind production in both hemispheres (e.g. Trenberth and Olson 1988; Lu et al. 2009). Our evaluation provides valuable information of the different statistical parameters that should be considered in seasonal post-processing methods as well as when comparing predictions with reanalysis. This is relevant for the development of wind speed applications and services.

The manuscript is organised as follows: the second section, Sect. 2, is devoted to the description of the ERA-Int and S4 datasets together with the definition of the statistical parameters used to characterize the probability distribution of 10 m wind speed. Afterwards, the Sect. 3 is focused on the characterization and comparison of the ERA-Int and S4 10 m wind speed distributions in different seasons and time-frames. In the Sect. 4 the main outcomes of the study are summarised.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Datasets

We have used 10 m wind speed monthly means from the ERA-Int reanalysis and S4 seasonal prediction system. Although higher altitude wind speed would be desirable for wind industry applications (e.g 100 m; Drechsel et al. 2012), unfortunately the state-of-the art seasonal prediction systems only provide the wind speed values at 10 m height. For that reason, and taking into account that 10 m level wind speed is a common proxy for higher altitude winds (e.g. Gryning et al. 2007) we focus our analysis on the near-surface (10 m) wind speed.

The ERA-Int reanalysis is a global atmospheric reanalysis issued by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). It spans 1979 to nowadays at a \(0.7^{\circ }\) resolution, and it is updated on a real-time basis (Dee et al. 2011). In comparison to the previous system, ERA-40 (Uppala et al. 2005), it shows multiple improvements such as the incorporation of the four-dimension variational data assimilation approach, 4D-Var, the increase of system resolution (\(\sim\)80 km) or the enhancement of the forecast system physics.

The S4 seasonal prediction system (Molteni et al. 2011) is a fully coupled general circulation system that provides operational multi-variable seasonal forecasts in a real-time basis at \(0.7^{\circ }\) resolution. In this study we focus on a 35-years period, 1981–2015, coming from the combination of the 30-years hindcast with the 5-years contemporary pool of forecasts (from 2011 onwards). The forecasts are initialised on the first day of every month and span 7 months into the future. Although there are 51 members for the start dates of February, May, August and November, and for every month since May 2011, the forecasts used in this study retained only 15 members to stay coherent with the remaining months. Predictions starting in August, September, October, November and December have been selected for DJF season; whereas for JJA, have been selected February, March, April, May and June.

2.2 Methods

In this work we have characterized the main properties of the wind speed probability density function of both ERA-Int and S4 based on the computation of five statistical parameters: mean, standard deviation, coefficient of variation, skewness and excess of kurtosis. We have also assessed the goodness of fit to a Gaussian distribution through the Shapiro–Wilks test (Wilks 2006). The analysis of the statistical parameters of the distribution has been done at interannual and intraseasonal basis to distinguish the contribution of each variability source (e.g. Achuthavarier and Krishnamurthy 2010; Luo et al. 2011). Interannual statistics reflect the properties of the seasonal mean distribution, i.e., how values vary from year to year for a particular season, whereas intraseasonal statistics reflect the average properties of the distribution inside a season, i.e., how values vary among the months of the season. The difference between each time frame is that at the intraseasonal scale we do not average the wind speed of the 3 months of the season, instead, we concatenate each group of three values in the time series. Finally, it is worth noting that dealing with the S4 implies each year having 15 times more elements than ERA-Int per grid-point, due to the inclusion of the 15-members forecast in the computation. In order to assess the statistical significance of the model-reanalysis differences we have used a bootstrapping method. This has also been applied to assess the significance of the excess kurtosis and skewness statistics in ERA-Int. Our approach consists in the following steps.

-

1.

Compute the statistic for both ERA-Int and S4.

-

2.

Repeat 1000 times the first point resampling the data with replacement.

-

3.

Compute the difference of each pair of 1000 values (it only applies when working with differences).

-

4.

Obtain the percentile 97.5th and 2.5th of the distribution of each statistic.

-

5.

If the zero value falls above the 97.5th or below the 2.5th percentile, then we can regard the statistic (or the difference) significantly different from 0 at 95% confidence level.

Subsequently we will introduce each of the statistical metrics used as well as the reasons for its choice. All these statistics are obtained for each grid-point and lead time separately. The mean, \({{\bar{x}}}\) , is the first moment of the distribution and a useful measure in order to characterize which are the usual conditions in one particular location/grid point.

From now on \(x_{i}\) refers to each value of the distribution; and, N, to the total number of elements in the distribution. The evaluation of the differences in the mean value (climatology) between the seasonal predictions and the reference dataset is a measure of the systematic error. Having computed the distribution’s central value we have characterized its variability around the mean based on the standard deviation (\(\sigma\)), which is the second central moment.

This is helpful to understand whether wind speed values spread far from the mean or, conversely, if they are clustered around it. From an end-user perspective this information is important because it is directly related to the capacity factor curves (e.g. Sinden 2007).

The coefficient of variation (cv) is a standardized measure of dispersion. It is often expressed as a percentage, and is defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean:

The smaller coefficient of variation the less dispersion is in the distribution. This is an interesting parameter because it relates the magnitude of the variability to the mean wind value. Thus, not only it allows to compare distinct wind regime regions (e.g. Bett et al. 2017), but it provides information on the areas with lower variability compared to the mean, which is important when studying appropriate spots for wind-farm installation (the production is easier to plan).

Skewness is a measure of the degree of symmetry related to the normal distribution, which indicates whether a sample has more values to the left of its mean (left-skewed), to the right (right-skewed) or it is symmetrically distributed around the mean (zero skewness) and it is defined:

Kurtosis is the fourth moment of the distribution and it measures the weight of the tails of a sample distribution. It can be defined as:

Kurtosis is often compared to that of a Standard Normal distribution, which equals 3, by subtracting 3 from the kurtosis value, yielding what is known as ‘excess kurtosis’. In a positive (negative) excess kurtosis the weight of the tails is lower (higher) than for the Gaussian distribution. That is, the probability of an extreme located in the tails of the distribution is also lower (higher) than for the Gaussian distribution.

The goodness of fit assesses how closely a sample resembles a specific distribution. In our case we have assessed how close is our sample data to a normal distribution. Although instantaneous values or daily accumulations of many climatic variables do not have Gaussian distributions, at interannual or intraseasonal time scales the distributions tend to be ‘near-normal’ in accordance with the central limit theorem (Wilks 2006).

The evaluation of the goodness of fit is based on the Shapiro–Wilks test (Shapiro and Wilk 1965), which allows to quantify how similar is the distribution to a normal one. This test is a statistical hypothesis testing process whose null hypothesis is whether the distribution of a z variable for N values (\(z_{1}\), ...\(z_{N}\)) comes from a normally distributed population. The statistic that is employed in the hypothesis contrast is calculated as follows:

Where \(z_{i}\) are the ordered sample values (\(z_{1}\) is the smallest) and the \(a_{i}\) are constants that depend on the mean, variance and covariance matrix. The null hypothesis is that the population is normally distributed. Therefore, if the p-value computed with the statistic (6) is lower than a pre-set significance level (normally 95%), then the null hypothesis is rejected and the distribution is considered not normal. Since the skewness and kurtosis are another way for assessing the normality of the distribution, the outcomes and discussion linked to the goodness of fit are provided as Supplementary Material. All these statistical parameters are important to characterize the statistical distributions from both the model and the reanalysis. Besides, their difference is useful to identify which specific features of the statistical distributions are distinct between the prediction and reference datasets.

3 Results

In this section we present the results for DJF and JJA seasons at inter-annual and intraseasonal time scales. We start by analysing the results from ERA-Int and, afterwards, we assess the differences between S4 and the aforementioned reanalysis. To avoid cluttering we only provide images for DJF (results for JJA season are in supplementary material).

3.1 ERA-Int

The spatial patterns of the mean wind speed (climatology) for interannual and intraseasonal time scales are equal because the mean computation is independent of the number of steps (or the order) in which the mean is applied (e.g. Fig. 1a, b). For DJF, the climatology shows a widespread area of high wind speeds in the northern and southern extra-tropical oceans, with secondary maxima around 20\(^\circ\) north and south (Fig. 1a, b). The maximum wind speeds are over the oceans while the minimum values lie inland, with generally stronger winds in the Northern Hemisphere. In fact, the wind speed over land is generally less than half the observed over the oceans. This behaviour is a consequence of the increased roughness over the continents due to relief. For JJA, the maximum wind speeds are restricted to the Southern Hemisphere, around the extra-tropics and in the Indian Ocean, where the Monsoon structure is clear (Fig. 6a, b in the Supplementary Material). It is worth noting that the maximum wind speed difference between both hemispheres is more noticeable in JJA than in DJF, probably as a result of the stability of the southern circumpolar storm-track structure (Chang et al. 2002). Nevertheless, in both seasons the maximum wind speeds are observed over the oceans, with the minimum values settled over land.

The spatial patterns of the standard deviation inform us about the variability of the wind speed. Both DJF (Fig. 1c, d) and JJA (Fig. 6c, d in the Supplementary Material) show interannual values much lower than the intraseasonal. These differences are expected since month to month variations are normally bigger than interannual changes. For DJF the strongest variability is over the oceans and, more specifically, in the Northern Hemisphere where there is a region of high variability in the north-eastern Atlantic (Fig. 1c, d). This particular area contains the tail of the North-Atlantic stormtrack, where the storms enter the continent (Chang et al. 2002). Moving to the southern oceans, there is a strong variability region in the maritime continent (Indonesia) that propagates northwards. Conversely to DJF, JJA shows less variability (Fig. 6c, d in the Supplementary Material). Its maximum values are centred in the northern tropical regions and the southern Antarctic Ocean. Its worth noting that the differences between DJF and JJA are more remarkable in the Northern Hemisphere than in the Southern counterpart, probably due to the larger oceanic area in the latter.

Global 10 m wind speed probability distribution parameters from ERA-Int. They are computed for DJF at interannual and intraseasonal time-scales spanning the period 1981–2015. In skewness and excess kurtosis the hatching denotes regions where the values are different from 0 at 95% confidence level computed with a bootstrapping method. a Interannual climatology, b intraseasonal climatology, c interannual standard deviation, d intraseasonal standard deviation, e interannual coefficient of variation, f intraseasonal coefficient of variation, g interannual skewness, h intraseasonal skewness, i interannual excess kurtosis, j intraseasonal excess kurtosis

The coefficient of variation is the parameter displaying the greatest difference between the spatial patterns at interannual and intraseasonal time-scales (DJF, Fig. 1e, f; and JJA, Fig. 6e, f in the Supplementary Material). This is logical since it includes the second moment (standard deviation) and this tends to be higher at intraseasonal level than interannual. In DJF the greatest values are seen in the tropical Pacific and Indian Oceans and, also, the Greenland coast and western European regions (Fig. 1e, f). In JJA, conversely to DJF, the largest values are found only in the inter-tropical oceans, generally to the north of the Equator (Fig. 6e, f in the Supplementary Material).

The spatial patterns for the third moment (skewness) are noisy at interannual and intraseasonal level and for both seasons DJF (Fig. 1g, h) and JJA (Fig. 6g, h in the Supplementary Material). However, there are still some structures that can be outlined. Intraseasonal DJF and JJA show some prevalence of positive skewness over the continents (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Material Fig. 6h) and positive values over the equatorial line that are surrounded by negative ones. Additionally, around 30\(^\circ\) north and south to the Equator there is a global strip of positive values which is more evident in DJF (Fig. 1h) than JJA (Fig. 6h in the Supplementary Material). Finally, in DJF, we find positive values in the Arctic Ocean and negative skewness in the Antarctic Ocean. These structures are interesting because they highlight the influence of intraseasonal circulation processes on 10 m wind speed distribution. At interannual time scales the only remarkable structure is the dipole of the Eastern Pacific that can be found both in DJF and JJA and that could be linked to the ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation; Fig. 1g and Supplementary Material Fig. 6g).

The excess kurtosis, derived from the fourth moment compared to the normal, is interesting because it depicts some predominance of slightly negative values worldwide for both seasons, specially at interannual time scales (Fig. 1i and Supplementary Material Fig. 6i). This indicates that the wind speed distribution has heavier tails than a normal distribution, and consequently a higher than normal frequency of ocurrence of wind speed extreme events in that particular region. Besides, the most interesting structure lies in the Eastern Pacific, where a patch of positive values can be identified at both time frames and seasons (DJF, Fig. 1i, j; and JJA, Supplementary Material Fig. 6i, j), therefore the outliers are more frequent in that area than a gaussian distributed variable (Figs. 4a, c, 5a, c).

3.2 Differences between S4 and ERA-Int

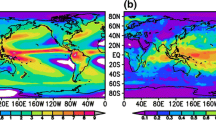

In this section we are evaluating the S4 predictions, with November (DJF) and May (JJA) start dates, against the reference data from ERA-Int using the parameters of the wind speed distribution (see supplementary material for wind speed distribution obtained with S4, Supplementary Material Figs. 7, 8). We limit the study to the first lead time because it retains some degree of predictability at extra-tropical latitudes (e.g. Doblas-Reyes et al. 2013) and, because the differences between start dates are rather small as it is illustrated in Fig. 2. This figure shows the S4 biases for DJF and JJA computed for three different start dates.

Global 10 m wind speed S4 biases relative to ERA-Int. They are computed for DJF and JJA considering the period 1981–2015 for 0, 2 and 4 months lead time. a DJF Lead 0, December initialization. b JJA Lead 0, June initialization. c DJF Lead 2, October initialization. d JJA Lead 2, April initialization. e DJF Lead 4, August initialization. f JJA Lead 4, February initialization

These results show that the seasonal bias is not dependent on the start date of the prediction. This might be due to the influence of mixing different lead times when building the season (e.g. DJF is built with the start date of November, which combines 1 month lead time for December, 2 months lead time for January and 3 months lead time for February). However, this is an hypothesis that has to be further studied but is out of the scope of this research.

Differences in climatology for DJF (Fig. 3a, b and JJA Fig. 9a, b from the Supplementary Material) seasons show that S4 has a systematic positive bias worldwide. More specifically, in DJF (Fig. 3a, b) the positive discrepancies lie in the inter-tropical oceans, eastern Siberia and western Canada. Regarding the areas where the S4 underestimates wind speeds, they are notorious in the Himalayan region, the Atlantic ocean close to the western coast of Equatorial Africa and the central and eastern Pacific ocean. S4 overestimates the values over the oceans in JJA (Fig. 9a, b from the Supplementary Material), especially in the inter-tropics and the Australia southern oceanic region and underestimates wind speeds in the eastern Pacific (near the Colombian coast), in the northern tropical Atlantic, in a strip of land between 20\(^\circ\) and 40\(^\circ\) north covering African and Asian territories and, also, in the Arctic ocean.

The differences in the standard deviation patterns at interannual and intraseasonal have similar magnitude at global scale (Fig. 3c, d and Supplementary Material Fig. 9c, d), although the latter displays slightly higher absolute values. There is also no dominant overall sign, either in DJF and JJA. In DJF, at intraseasonal timescales (Fig. 3d), there is higher variability over Indonesia and Indian ocean along a broader region than at interannual timescales (Fig. 3c). At both time scales, there are positive values over Indonesia, central equatorial Pacific and, also, northwestern Pacific. Negative values, on the other hand, are present in northern Europe, Siberia and eastern equatorial Pacific. Positive (negatives) values of the differences indicate that the S4 overestimates (understimates) the variability displayed at ERA-Int. Considering JJA, the differences at interannual level are less pronounced than at intraseasonal, although they hold a similar spatial structure (Fig. 9c, d from the Supplementary Material). In this case the interesting areas lie in the inter-tropics, especially in the maritime continent (where the S4 underestimates ERA-Int), the Bengal Bay (where S4 overestimates) and the equatorial Atlantic and Pacific Oceans (S4 underestimates variability in the Pacific; and overestimates in the Atlantic).

Differences in wind speed probability distribution parameters computed for DJF at interannual and intraseasonal time-scales (S4 minus ERA-Int) for the period 1981–2015. The seasonal predictions for DJF have been initialized the 1st of November. The hatching means the values are different from 0 at 95% confidence level computed with a bootstrapping method. a Interannual climatology, b intraseasonal climatology, c interannual standard deviation, d intraseasonal standard deviation, e interannual coefficient of variation, f intraseasonal coefficient of variation, g interannual skewness, h intraseasonal skewness, i interannual excess kurtosis, j intraseasonal excess kurtosis

The coefficient of variation differences show localised larger values at intraseasonal than interannual time frames, both for DJF and JJA (e.g. in the Indian Ocean, North America or Syberia; Fig. 3e, f and Supplementary Material Fig. 9e, f). An overestimation of the coefficient means that either the variability is too big or the mean, too small, always regarding ERA-Int reference. The increased value of the differences in several areas at the intraseasonal scale is due to variability between months within the same season tends to be higher than the interannual one. More specifically, in DJF the regions with more intense values can be found at the intertropical areas and a strip of land around 60\(^\circ\) north, from Scandinavia to Siberia (Fig. 3e, f). Intertropical regions present discrepancies at both time scales, being an underestimation of the cv by S4 for the most part of the Pacific Ocean, whereas an underestimation of the S4 is found mainly over the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In the strip of land from Scandinavia to Siberia the S4 underestimates the cv due to the intense underestimation of the S4 standard deviation over this area (Fig. 3c, d). There, it is also possible to find negative difference values of cv over Northern America, which are more intense at intraseasonal than at interannual time-scales. In JJA (Fig. 9e, f from the Supplementary Material), the inter-tropics is again the region where the magnitude differences is greater, particularly at intraseasonal time-scales, where negative (positive) values of the differences are found over central and western Pacific ocean, South America, Africa and Indian ocean (central Atlantic and Indian region) at most. Outside tropical zones, over land, there is an intensification of the negatives values over southern part of North America, northern Europe and Asia and South America. Similarly to what’s happening for standard deviation coefficient, the spatial amplitude of the cv values is higher in winter season than in summer and for the case of JJA higher at intraseasonal time-scales.

When studying skewness and excess kurtosis it is important to note that the S4 (Figs. 7g–j and 8g–j both from the Supplementary Material) is not capable of reproducing the structure of ERA-Int (Fig. 1g–j, Supplementary Material Fig. 6g–j), especially in the kurtosis case, where it only has non-zero values around the inter-tropics. Besides, these differences are mostly non significant at 95% confidence level, especially at interannual scales (except in winter intraseasonal excess kurtosis, where the differences are significant almost everywhere, Fig. 3h). This behaviour is also observed when assessing the statistical significance at a 95% confidence level in the ERA-Int (Fig. 1g–j). However, if we focus on the differences, in skewness they are more intense at interannual than intraseasonal time-scales (Fig. 3g, h and from the Supplementary Material Fig. 9g, h). This means the third moment’s magnitude is better depicted by the S4 when considering months within a season than when gathering seasons in a year to year basis. It is worth remembering that regions with S4 underestimation (blue colors in Fig. 3g, h and from the Supplementary Material Fig. 9g, h) imply that the statistical distribution is more skewed to the right than the ERA-Int reference. This indicates that high values of 10 m wind speed are more probable for the S4 than for ERA-Int. In case of overestimation, the behaviour is the opposite (red colours in Fig. 3g, h and from the Supplementary Material Fig. 9g, h). Besides, the spatial difference patterns are very noisy, and they only barely resemble when assessing the same season. More specifically, the areas holding greater differences are located in the inter-tropics, specially in the central and eastern Pacific at inter-annual scales (Fig. 3g and from the Supplementary Material Fig. 9g). Moreover, in DJF interannual scale, the Arctic shows some consistent S4 overestimation (Fig. 3g). Finally, regarding JJA, the S4 underestimates skewness at interannual scales in the Antarctic Ocean.

Finally, when the differences in excess kurtosis are analyzed, we can see they are also more intense at interannual than intraseasonal level (Fig. 3i, j and from the Supplementary Material Fig. 9i, j). That said, we have to consider that S4 is not able to produce excess-kurtosis values large enough outside the inter-tropical region. Areas with S4 overestimation signal greater values of excess kurtosis than the ERA-Int and, thus, lighter tails than the reference. Conversely, regions with S4 underestimation signal smaller values of excess kurtosis than the ERA-Int and, hence, heavier tails. Having lighter (heavier) tails means that the S4 shows less (more) 10 m wind speed extreme values than ERA-Int. In DJF, interannually (Fig. 3i), the most interesting regions lie in the central inter-tropical Pacific where there is a region of S4 underestimation surrounded by overestimated areas; the northern extra-tropical Atlantic, with patches of S4 underestimation; and northern Europe, which shows an area of S4 overestimation. Intraseasonally (Fig. 3j), we can highlight the Southern Hemisphere, with patchy areas of more intense S4 overestimation and underestimation and the Arctic Ocean (with areas of intense S4 underestimation). Regarding JJA, it seems there is a predominance of positive values, mainly at interannual level (Fig 9i from the Supplementary Material). In this case, although the behaviour is even noisier, we can identify some patterns in the inter-tropics (mainly S4 overestimation) and in the southern Pacific Ocean (S4 underestimation).

3.3 The Shapiro–Wilks test

In this section we summarise the application of the Shapiro–Wilks test to evaluate whether the distribution of the 10 m wind speed for both of the ERA-Int and S4 fits to a Gaussian distribution. The evaluation is performed for DJF and JJA at interannual and intraseasonal time scales (Figs. 4, 5) as in the rest of the parameters of this study. In this test the null hypothesis is that the underlying distribution is of Gaussian type. We have established the significance confidence level at 95%, which means a rejection of the null hypothesis when the p-value is equal or below 0.05.

At intraseasonal time scales the regions that we cannot regard Gaussian for ERA-Int are basically in the inter-tropical region for JJA (Fig. 5c), and extended to some other areas in extra-tropical regions for DJF (Fig. 5a). Interannually these areas are more scarce (Figs. 4a, c), although it is worth noting that the tropical Pacific still shows some deviations from a gaussian distribution. In S4 the number of territories with p value under 0.05 (i.e. where we can reject the null hypothesis) is superior to those found for ERA-Int (Figs. 4b, d, 5b, d). At intraseasonal time scale we find some areas in the extra-tropics where the null hypothesis is not rejected (Fig. 5b, d), although these areas are narrower than those at interannual level (Fig. 4b, d).

Shapiro–Wilks goodness of fit test for ERA-Int and S4 interannual 10 m wind speed, considering the period 1981–2015. The seasonal predictions for DJF have been initialized the 1st of November; for JJA, they have been initilized the 1st of May. a DJF, ERA-Int, sample size 35. b DJF, S4, sample size 525. c JJA, ERA-Int, sample size 35. d JJA, S4, sample size 525

The number of values entering the Shapiro–Wilks test can explain the observed differences between ERA-Int/S4 and interannual/intraseasonal time-scales. In fact, looking at Figs. 4, 5 we see that in Figs. 4a, c there are 35 values of sample size for each grid-point; in Fig. 5a, c 105 (\(35\times 3\)); in Fig. 4b, d there are 525 (\(35\times 15\)) values; and in Fig. 5b, d 1575 (\(35\times 3\times 15\)). For instance, in the intraseasonal configuration there is threefold more data entering the test than for the interannual case. Furthermore, when considering ERA-Int and S4 there are 15 times more values in the latter (one for each ensemble member).

Therefore, the rate to which the goodness of fit Shapiro–Wilks test rejects the hypothesis of normality is notably dependent on the sample size. This is not a unique feature of the Shapiro–Wilks test, but a general characteristic of every hypothesis testing relying on the p-value approach, because the power of a test depends, both, on the effect size and the sample size (e.g. Marsh and McDonald 1988; Sullivan and Feinn 2012).

Shapiro–Wilks goodness of fit test for ERA-Int and S4 intraseasonal 10 m wind speed, considering the period 1981–2015. The seasonal predictions for DJF have been initialized the 1st of November; for JJA, they have been initilized the 1st of May. a DJF, ERA-Int, sample size 105. b DJF, S4, sample size 1575. c JJA, ERA-Int, sample size 105. d JJA, S4, sample size 1575

4 Discussion and conclusions

In this work we have outlined the main characteristics of the global 10 m wind speed distribution of ERA-Int reanalysis and used this information to validate the corresponding S4 distribution. We have applied a set of six statistical diagnostics: mean value, standard deviation, coefficient of variation, kurtosis, skewness and goodness of fit Shapiro–Wilks test and studied them for DJF and JJA seasons at interannual and intraseasonal time scales and for all possible start dates. This diagnostic work helps to locate the hot-spot regions for the study of wind speed from a bias adjustment standpoint, which differ depending on the parameter considered.

In ERA-Int climatology (mean) DJF shows a widespread area of higher wind speeds in the northern and southern extra-tropical oceans, with secondary maxima around 20\(^\circ\) north and south. In JJA, on the other hand, the maximum wind speeds are restricted to the Southern Hemisphere, around the extra-tropics and in the Indian Ocean. In both seasons the maximum wind speeds are observed over the oceans, with the minimum values over land. The spatial standard deviation patterns for DJF are similar at interannual and intraseasonal time scales. In DJF the greatest standard deviation values are over the oceans, and in JJA, in the northern tropical regions and the southern Antarctic Ocean. The coefficient of variation, on the other hand, is the parameter displaying the greatest difference between interannual and intraseasonal frameworks. In DJF the most intersting areas are the southern tropical Pacific and Indian Oceans and, also, in Europe, the Greenland coast and western European regions. In JJA, contrary to DJF, the largest values are found only in the inter-tropical oceans, generally to the north of the Equator. In skewness and excess kurtosis the noisiness is the prevalent characteristic for both DJF and JJA and, also, at interannual and intraseasonal time scales. In skewness, around 30\(^\circ\) north and south to the Equator there is a global strip of positive values which is more evident in DJF than JJA. Additionally, in DJF, we find positive values in the Arctic Ocean and negative skewness in the Antarctic. For the excess kurtosis, the most interesting structure lies in the Eastern Pacific, where a patch of positive values can be identified in boh seasons and time scales. Regarding the seasonal S4 bias, it is almost independent of the lead time.

The differences in the first statistical parameter (mean) reveal that S4 systematically overestimates wind speed at global scales, except for some specific regions in which S4 understimates it. For standard deviation, the higher differences are found in the inter-tropical areas and the intraseasonal frame for JJA season, whereas for DJF the highest differences are found in the tropical areas but in Norhern Europe also. The disparity of values between ERA-Int and S4 is larger in DJF than in JJA, and over the oceans than over the continents. The coefficient of variation differences show larger values at intraseasonal than interannual time frames, both for DJF and JJA. More specifically, in DJF the inter-tropics is the area where the greatest discrepancies can be observed. The other significant area is a strip of land around 60\(^\circ\) north, from Scandinavia to Siberia, where the S4 underestimates the cv due to the intense uderstimation of the S4 standard deviation over this area. Regarding JJA, the inter-tropics is again the region where the magnitude differences is greatest. When studying skewness and excess kurtosis the S4 is not capable of reproducing the finer structure of ERA-Int, specially in the excess kurtosis case outside the inter-tropics (near zero values). Differences in skewness are more intense at interannual than intraseasonal time-scales. More specifically, the areas holding greater differences are located in the inter-tropics, specially in the central and eastern Pacific at inter-annual scales. Moreover, in DJF interannual scale, the Arctic shows some consistent S4 overestimation. Finally, regarding JJA, the S4 uderstimates skewness at interannual scales in the Antarctic Ocean. Regarding the excess kurtosis, the difficulty of the S4 to produce values substantially different from zero outside the inter-tropics might be due to the effect of the sample size on the fourth moment. However, since the effect of the S4 ensemble dimension on the kurtosis and the other moments seems different, a more thorough analysis on the reasons behind this behaviour might be needed to confirm or refute this hypothesis.

One conclusion we can draw from the results obtained is that while the S4 is able to approximately reproduce the structure of the first two moments of the distribution, it has much more difficulties when dealing with the third and fourth moment patterns or the combination of the first two (e.g. coefficient of variation). This is an outcome that should be considered when assessing the performance and suitability of any post-processing method, pushing towards the use of bias adjustment methods that take into consideration not only the first and second moments but the complete distribution, as for example the calibration method used in Torralba et al. (2017).

Eventually, regarding the goodness of fit to a normal distribution, the intertropical areas and the intraseasonal time-scales cannot be regarded normally fitted (for the extratropical, this is only true at intraseasonal scales). However, the way in which this normality is violated is different depending on the season, the time scale and the dataset. It is possible that some of these differences are consequence of the characteristics of the S4 or the number of values entering the Shapiro–Wilks goodness of fit test. In fact, in the intraseasonal configuration there is threefold more data entering the Shapiro–Wilks test than for the interannual case (when considering ERA-Int and S4 there are 15 times more values in the latter due to the ensemble size). Therefore, we have found that the rate to which the goodness of fit Shapiro–Wilks test rejects the hypothesis of normality is notably dependent on the sample size and, thus, the results obtained should be regarded with caution.

These results encourage us to proceed further in our research by validating the S4 with other reanalyses and comparing it with other seasonal prediction systems (e.g. ERA5 reanalysis or ECMWF System 5 seasonal forecast system). Furthermore, we will also seek the collaboration of wind industry end-users to tailor future experimental suites to test the usability of commonly used post-processing techniques (either downscaling or bias correction).

References

Achuthavarier D, Krishnamurthy V (2010) Relation between intraseasonal and interannual variability of the South Asian monsoon in the National centers for environmental predictions forecast systems. J Geophys Res 115:D08104

Amengual A, Homar V, Romero R, Alonso S, Ramis C (2012) Projections of the climate potential for tourism at local scales: Application to Platja de Palma, Spain. Int J Climatol 32(14):2095–2107

Andres N, Vegas Galdos F, Lavado Casimiro WS, Zappa M (2014) Water resources and climate change impact modelling on a daily time scale in the Peruvian Andes. Hydrol Sci J 59(11):2043–2059

Benestad RE, Hanssen-Bauer I, Chen D (2008) Empirical-statistical downscaling. World Scientific Pub Co Inc, Oslo

Bett PE, Thornton HE, Clark RT (2017) Using the twentieth century reanalysis to assess climate variability for the European wind industry. Theor Appl Climatol 127(1–2):61–80 arXiv:1409.5359v1

Chang EKM, Lee S, Swanson KL (2002) Storm track dynamics. J Clim 15(16):2163–2183

Chen J (2011) Development of offshore wind power in China. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 15(9):5013–5020

Cornes RC, Jones PD (2013) How well does the ERA-Interim reanalysis replicate trends in extremes of surface temperature across Europe? J Geophys Res Atmos 118(18):10,262–10,276

Costa A, Crespo A, Navarro J, Lizcano G, Madsen H, Feitosa E (2008) A review on the young history of the wind power short-term prediction. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 12(6):1725–1744

Dee DP, Uppala SM, Simmons AJ, Berrisford P, Poli P, Kobayashi S, Andrae U, Balmaseda MA, Balsamo G, Bauer P, Bechtold P, Beljaars ACM, van de Berg L, Bidlot J, Bormann N, Delsol C, Dragani R, Fuentes M, Geer AJ, Haimberger L, Healy SB, Hersbach H, Hólm EV, Isaksen L, Köllberg P, Köhler M, Matricardi M, Mcnally AP, Monge-Sanz BM, Morcrette JJ, Park BK, Peubey C, de Rosnay P, Tavolato C, Thépaut JN, Vitart F (2011) The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q J R Meteorol Soc 137(656):553–597

Delsole T, Shukla J (2010) Model fidelity versus skill in seasonal forecasting. J Clim 23:4794–4806

Doblas-Reyes FJ, García-Serrano J, Lienert F, Biescas AP, Rodrigues LRL (2013) Seasonal climate predictability and forecasting: status and prospects. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change 4(4):245–268

Drechsel S, Mayr GJ, Messner JW, Stauffer R (2012) Wind speeds at heights crucial for wind energy: measurements and verification of forecasts. J Appl Meteorol Climatol 51(9):1602–1617

Edenhofer O, Pichs-Madruga R, Sokona Y, WG3 I (2014) Climate Change 2014: mitigation of climate change. http://arxiv.org/abs/1011.1669v3

Firestone J, Archer CL, Gardner MP, Madison JA, Prasad AK, Veron DA (2015) Opinion: the time has come for offshore wind power in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112(39):11,985–11,988

Gryning SE, Batchvarova E, Brümmer B, Jørgensen H, Larsen S (2007) On the extension of the wind profile over homogeneous terrain beyond the surface boundary layer. Bound Layer Meteorol 124(2):251–268

Hewitt C, Mason SJ, Walland D (2012) The global framework for climate services. Nat Clim Change 2(12):831–832

Higgins P, Foley AM (2013) Review of offshore wind power development in the United Kingdom. In: 2013 12th international conference on environment and electrical engineering, pp 589–593

Jung J, Broadwater RP (2014) Current status and future advances for wind speed and power forecasting. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 31:762–777

Kiss P, Varga L, Jánosi IM (2009) Comparison of wind power estimates from the ECMWF reanalyses with direct turbine measurements. J Renew Sustain Energy 1(3):033,105

Lorenz T, Barstad I (2016) A dynamical downscaling of ERA-Interim in the North Sea using WRF with a 3 km grid-for wind resource applications. http://arxiv.org/abs/1006.4405v1

Lu X, McElroy MB, Kiviluoma J (2009) Global potential for wind-generated electricity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(27):10,933–10,938

Luo D, Diao Y, Feldstein SB (2011) The variability of the Atlantic storm track and the North Atlantic oscillation: a link between intraseasonal and interannual variability. J Atmos Sci 68(3):577–601

Marcos R, Turco M, Bedía J, Llasat MC, Provenzale A (2015) Seasonal predictability of summer fires in a mediterranean environment. Int J Wildland Fire 24(8):1076–1084

Marcos R, Carmen M, Quintana-seguí P, Turco M (2017) Use of bias correction techniques to improve seasonal forecasts for reservoirs : a case-study in northwestern mediterranean. Sci Total Environ 610:64–74

Marsh HW, McDonald JRBRP (1988) Goodness-of-fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis: the effect of sample size. Psychol Bull 103(3):391–410

Molteni F, Stockdale T, Balmaseda MA, Balsamo G, Buizza R, Ferranti L, Magnusson L, Mogensen K, Palmer TN, Vitart F (2011) The new ECMWF seasonal forecast system (System 4). ECMWF Tech Memo 656(November):49

Ogutu G, Supit I, Hutjes R (2016) Probabilistic maize yield simulation over East Africa using ensemble seasonal climate forecasts. Geophys Res Abstr EGU Gen Assem 18:2016–17,111

Palmer T, Shutts G, Hagedorn R, Doblas-Reyes F, Jung T, Leutbecher M (2005) Representing model uncertainty in weather and climate prediction. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 33(1):163–193

Parker WS (2016) Reanalyses and observations: what’s the difference? Bull Am Meteorol Soc 97(9):1565–1572

Pryor SC, Barthelmie RJ, Schoof JT (2006) Inter-annual variability of wind indices across Europe. Wind Energy 9:27–38

Rose S, Apt J (2015) What can reanalysis data tell us about wind power? Renew Energy 83:963–969

Ruffault J, Martin-StPaul NK, Duffet C, Goge F, Mouillot F (2013) Projecting future drought in Mediterranean forests: bias correction of climate models matters!. Theor Appl Climatol 117(1):113–122

Shapiro SS, Wilk MB (1965) An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 52(3):591–611 arXiv:1011.1669v3

Sinden G (2007) Characteristics of the UK wind resource: long-term patterns and relationship to electricity demand. Energy Policy 35(1):112–127

Škerlak B, Sprenger M, Wernli H (2014) A global climatology of stratosphere–troposphere exchange using the ERA-Interim data set from 1979 to 2011. Atmos Chem Phys 14(2):913–937

Stockdale TN, Anderson DLT, Balmaseda MA, Doblas-Reyes FJ, Ferranti L, Mogensen K, Palmer TN, Molteni F, Vitart F (2011) ECMWF seasonal forecast system 3 and its prediction of sea surface temperature. Clim Dyn 37(3):455–471

Sullivan GM, Feinn R (2012) Using effect size: or why the p value is not enough. J Grad Med Educ 4(3):279–282 arXiv:1011.1669v3

Tompkins AM, di Giuseppe F (2015) Potential predictability of malaria in Africa using ECMWF monthly and seasonal climate forecasts. J Appl Meteorol Climatol 54(3):521–540

Torralba V, Doblas-Reyes FJ, MacLeod D, Christel I, Davis M (2017) Seasonal climate prediction: a new source of information for the management of wind energy resources. J Appl Meteorol Climatol 56(5):1231–1247

Trenberth KE, Olson JG (1988) An evaluation and intercomparison of global analyses from the national meteorological center and the European centre for medium range weather forecasts. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 69(9):1047–1057

Uppala SM, Kallberg PW, Simmons AJ, Andrae U, Bechtold VDC, Fiorino M, Gibson JK, Haseler J, Hernandez A, Kelly GA, Li X, Onogi K, Saarinen S, Sokka N, Allan RP, Andersson E, Arpe K, Balmaseda MA, Beljaars ACM, Berg LVD, Bidlot J, Bormann N, Caires S, Chevallier F, Dethof A, Dragosavac M, Fisher M, Fuentes M, Hagemann S, Hólm EV, Hoskins BJ, Isaksen L, Janssen PAEM, Jenne R, Mcnally AP, Mahfouf JF, Morcrette JJ, Rayner NA, Saunders RW, Simon P, Sterl A, Trenberth KE, Untch A, Vasiljevic D, Viterbo P, Woollen J (2005) The ERA-40 re-analysis. Q J R Meteorol Soc 131(612):2961–3012

Wilks DS (2006) Statistical methods in the atmospheric sciences. Academic Press, London, http://arxiv.org/abs/1011.1669v3

Zhu X, Genton MG (2012) Short-term wind speed forecasting for power system operations. Int Stat Rev 80(1):2–23

Acknowledgements

We thank the S2S4E (GA776787), NEWA (PCIN-2014-012-C07-07), EUCP (GA776613), ERA4CS-INDECIS (GA690462), ERA4CS-MEDSCOPE (GA690462) and RESILIENCE (CGL2013-41055-R) projects funding for allowing us to carry out this research. We also acknowledge the ECMWF for the provision of the ECMWF System 4 ensemble re-forecast and the ERA-Interim reanalysis datasets.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Marcos, R., González-Reviriego, N., Torralba, V. et al. Characterization of the near surface wind speed distribution at global scale: ERA-Interim reanalysis and ECMWF seasonal forecasting system 4. Clim Dyn 52, 3307–3319 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-018-4338-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-018-4338-5