Abstract

The role of the oceanic water cycle in the record-breaking 2015 warm-season precipitation in the US is analyzed. The extreme precipitation started in the Southern US in the spring and propagated northward to the Midwest and the Great Lakes in the summer of 2015. This seasonal evolution of precipitation anomalies represents a typical mode of variability of US warm-season precipitation. Analysis of the atmospheric moisture flux suggests that such a rainfall mode is associated with moisture export from the subtropical North Atlantic. In the spring, excessive precipitation in the Southern US is attributable to increased moisture flux from the northwestern portion of the subtropical North Atlantic. The North Atlantic moisture flux interacts with local soil moisture which enables the US Midwest to draw more moisture from the Gulf of Mexico in the summer. Further analysis shows that the relationship between the rainfall mode and the North Atlantic water cycle has become more significant in recent decades, indicating an increased likelihood of extremes like the 2015 case. Indeed, two record-high warm-season precipitation events, the 1993 and 2008 cases, both occurred in the more recent decades of the 66 year analysis period. The export of water from the North Atlantic leaves a marked surface salinity signature. The salinity signature appeared in the spring preceding all three extreme precipitation events analyzed in this study, i.e. a saltier-than-normal subtropical North Atlantic in spring followed by extreme Midwest precipitation in summer. Compared to the various sea surface temperature anomaly patterns among the 1993, 2008, and 2015 cases, the spatial distribution of salinity anomalies was much more consistent during these extreme flood years. Thus, our study suggests that preseason salinity patterns can be used for improved seasonal prediction of extreme precipitation in the Midwest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the spring of 2015, an extreme rainfall event affected the Southern US and triggered record-breaking floods. The extreme rainfall marked the wettest spring in the state records of Oklahoma and Texas, where the total precipitation more than doubled the springtime rainfall climatology (1950–2014). The resultant flooding caused extensive losses in the economy and agriculture, and claimed more than 20 lives (NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information 2016). The anomalous rainfall propagated northward in the summer of 2015 and resulted in above normal precipitation in the US Midwest and the Great Lakes. The excessive precipitation refilled the Great Lakes and brought the lake levels back to historical averages. According to the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (2016), the year 2015 was the second wettest year on record for the Midwest.

This 2015 extreme event has been attributed to the coexistence of an intensified Great Plains Low-Level Jet (GPLLJ) and an anomalous upper tropospheric trough over the Southwest US (Wang et al. 2015). The coupling between the two circulation systems can create a baroclinically unstable region over the Southern US that dynamically sustains the heavy rainfall events (Wang and Chen 2009; Harding and Snyder 2015). Such a circulation feature is further attributed to the interplay between anthropogenic forcing and the developing El Niño in the tropical Pacific (Wang et al. 2015; Steinschneider and Lall 2016).

While the atmospheric circulation provides a background condition for the precipitation, extreme rainfall cannot be sustained without moisture transport from the oceans (Trenberth et al. 2003; Stohl and James 2004; Chan and Misra 2010). Over the ocean, the net moisture source regions are primarily located in the subtropics, where evaporation is enhanced by the prevailing wind but precipitation is depressed owing to the presence of subtropical high pressures (e.g., Schmitt 1995; Wu et al. 2009; Lagerloef et al. 2010a; Schanze et al. 2010; Gimeno et al. 2012). On a yearly basis, evaporation exceeds precipitation by 1–3 m, resulting in a net moisture export from the subtropics (Schanze et al. 2010; Trenberth et al. 2011). Climatologically, about a third of the subtropical moisture converges on land and becomes an integral part of the terrestrial water cycle (Gimeno et al. 2010; van der Ent et al. 2010). Thus, the variability of the subtropical water cycle can significantly modulate precipitation on land (Gimeno et al. 2013; Castillo et al. 2014; Li et al. 2016a, b).

Our recent study has shown that the springtime water cycle in the subtropical North Atlantic significantly influences the moisture abundance for synchronized precipitation in the Southern US and modulates summer precipitation in the US Midwest (Li et al. 2016b). In the spring, increased moisture export from the subtropical North Atlantic tends to converge in the Southern US and thus elevate soil moisture content in the local area (Li et al. 2016b). Throughout the season, the increased soil moisture content is preserved because of the 3–6 month soil moisture memory in the Southern US (Wu et al. 2007; Dirmeyer et al. 2009). Soil moisture in this region actively couples with the overlying atmosphere (Koster et al. 2004), which in turn influences the regional water cycle both thermodynamically and dynamically (Li et al. 2016b). Along with the summertime intensification of the northward-flowing GPLLJ, the anomalously high precipitation propagates into the US Midwest (Li et al. 2016b). The North Atlantic water cycle-induced US precipitation change documented by Li et al. (2016b) closely resembled the seasonal evolution of precipitation anomalies in 2015, and allowed its accurate forecasting (Schmitt et al. 2015). This motivated us to explore the contribution of the North Atlantic water cycle to the 2015 extreme precipitation event, which lay beyond the analysis period covered in Li et al. (2016b).

Furthermore, the water cycle variability in the subtropical North Atlantic leaves an imprint on sea surface salinity (SSS), in that the freshwater flux is the ultimate source of SSS variations (Schmitt 1995; Mignot and Frankignoul 2003; Lagerloef et al. 2010a; D’Addezio and Bingham 2014). The close connection between salinity, the subtropical water cycle, and terrestrial precipitation enables SSS in certain regions of the subtropical oceans to be utilized as a rainfall predictor (Li et al. 2016a, b). Evidence is presented in Li et al. (2016b) that SSS in the northwestern portion of the subtropical North Atlantic provides even higher predictive skills for US Midwest summer precipitation than SST-based predictors. Predicting precipitation extremes remains challenging but of immense socioeconomic value. We will further evaluate the performance of SSS in predicting the 2015 events, as well as the extreme precipitation events in the historical records.

The rest of the manuscript is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the data and methods used in this study. In Sect. 3, atmospheric moisture flux in the 2015 extreme event is presented, and the contributions of the subtropical North Atlantic water cycle to the rainfall extreme are quantified. Section 4 analyzes subtropical salinity signals associated with the 2015 extreme events, as well as the predictability of historical extremes using the salinity precursors. Conclusions obtained in this study are summarized in Sect. 5.

2 Data and methods

2.1 Precipitation and atmospheric reanalysis datasets

The precipitation data used in this study are from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center (CPC) US Unified Precipitation for 1950–2006 and from the Real-Time US Daily Precipitation Analysis for the 2007–2015. The dataset is at 0.25° × 0.25° spatial resolution (Higgins et al. 2000). Seasonal mean precipitation is derived from the accumulated daily precipitation for the spring (March–April–May; MAM) and summer (June–July–August, JJA) seasons. To study the moisture transport between ocean and the conterminous US, we calculated atmospheric moisture flux \(\left( {\frac{1}{g}\mathop \smallint \nolimits_0^{{p_s}} q\vec V{\text{d}}p} \right)\) using six different reanalysis datasets (Table 1). The moisture flux calculated from the six datasets is averaged over their overlapping periods (Table 1) to minimize the uncertainties introduced by the choice of reanalysis datasets (Li et al. 2013). The moisture flux divergence (MFD) is quantified as \(MFD=\frac{1}{g}\nabla \cdot \mathop \smallint \limits_0^{{p_s}} q\vec V{\text{d}}p\), which represents the net moisture input or output for each grid cell. From the MFD, we derived the divergent component of the moisture flux by solving the Poisson equations (Lynch 1988). The divergent component and MFD enable us to identify the net moisture output regions associated with the anomalous precipitation (Chen and Pfaendtner 1993). The units of MFD have been converted to mm day−1, in order to be consistent with precipitation.

Furthermore, to explore the sea surface salinity (SSS) and sea surface temperature (SST) precursors of the extreme events, the UK Met Office EN4.1.1 salinity archive (Good et al. 2013) and Extended Reconstructed SST (ERSST) dataset (Smith et al. 2008) were used, respectively. The source data of EN4.1.1 salinity are observation based, including the World Ocean Database 2005, the global temperature–salinity profile program, and the Argo float data. The salinity profiles from these observational sources are quality controlled. The data used in this study are the objectively analyzed data with 1° × 1° spatial resolution and monthly temporal resolution. The SSS refers to salinity at 5-m depth. The linear trend in the salinity data was removed prior to the analysis.

2.2 CEOF analysis

To study the seasonally evolving modes of precipitation variability in the conterminous US, combined empirical orthogonal function (CEOF) analysis is applied to the spring (MAM) and summer (JJA) precipitation (Weare and Nasstrom 1982; Bretherton et al. 1992) during the 1950–2015 period. The JJA precipitation usually has higher temporal variance than its MAM counterpart (Higgins et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2010a). To avoid the dominance of JJA precipitation variability in the combined vector, we normalized both the MAM and JJA precipitation anomalies by their standard deviation prior to the analysis. The normalized MAM and JJA precipitation was first concatenated to form a combined data matrix P: \({\varvec{P}}=\left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{\varvec{P}}_{{\mathbf{MAM}}}}} \\ {{P_{JJ\mathbf{A}}}} \end{array}} \right)\). Then, the pair-wise covariance between all possible combinations of the precipitation fields were calculated to obtain the covariability matrix \({\varvec{R}}={\varvec{P}}{{\varvec{P}}^{\varvec{T}}}\). The ith eigenvectors of R (i.e., the i-th CEOF mode) can be calculated as \({{\varvec{E}}^{\varvec{i}}}=\left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\varvec{E}}_{{\text{MAM}}}^{\varvec{i}}} \\ {{\varvec{E}}_{{\text{JJA}}}^{\varvec{i}}} \end{array}} \right)\), where \({\varvec{E}}_{{\text{MAM}}}^{\varvec{i}}\) is the ith CEOF mode of MAM precipitation, and \({\varvec{E}}_{{\text{JJA}}}^{\varvec{i}}\) is the ith CEOF of JJA precipitation. The eigenvalue corresponding to the ith eigenvector (E i) is λi, and the explained variance by the ith CEOF mode is \(\frac{{100{\lambda _i}}}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i=1}^N {\lambda _i}}}\%\). In addition, by projecting P to \({{\varvec{E}}^{\varvec{i}}}\), we are able to derive the ith principle component (Weare and Nasstrom 1982; Bretherton et al. 1992).

In addition, we composited the MFD and the divergent component of moisture flux on the CEOF principal component (PC) indices to examine the regional moisture balance and moisture transport associated with the precipitation variation. The composite samples are the years when the PC index exceeds one standard deviation (STD). The significance levels of the composite moisture flux are determined using the two-sample Hotelling’s t-squared test (Hotelling 1931). It is assumed that the divergent component (u, v) is distributed as two-variate normal distribution. The samples from the subset of PC >1STD is distributed as \(X \sim {N_2}\left( {{{\varvec{u}}_1},~{\Sigma _1}} \right)\) with mean vector u 1 and covariance matrix \({\Sigma _1}\); while the samples from subset PC<-1STD have the distribution \(Y \sim {N_2}\left( {{{\varvec{u}}_2},~{\Sigma _2}} \right)\). The null hypothesis is \({{\mathbf{u}}_1}={{\mathbf{u}}_2}\), meaning that the divergent component of moisture flux does not differ between the two opposite phases of a CEOF mode. The null hypothesis can be tested using the t-squared statistics: \({t^2}=\frac{{{n_x}{n_y}}}{{{n_x}+{n_y}}}{\left( {\bar x - \bar y} \right)^T}{W^{ - 1}}\left( {\bar x - \bar y} \right)\) which has the T 2 distribution, i.e., \({t^2} \sim {T^2}\left( {2,{n_x}+{n_y} - 2} \right)\). Here, \({n_x}\) and \({n_y}\) are the number of high and low PC cases. \(\bar x=\frac{1}{{{n_x}}}\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i=1}^{{n_x}} {x_i}\), \(\bar y=\frac{1}{{{n_y}}}\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i=1}^{{n_y}} {y_i}\) and \({W^{ - 1}}\) is the inverse matrix of W which is calculated as \(W=\frac{1}{{{n_x}+{n_y} - 2}}\left( {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i=1}^{{n_x}} \left( {{x_i} - \bar x} \right){{\left( {{x_i} - \bar x} \right)}^T}+\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i=1}^{{n_x}} \left( {{y_i} - \bar y} \right){{\left( {{y_i} - \bar y} \right)}^T}} \right)\). The null hypothesis can be rejected at \(\alpha\) significance level if \({t^2}>T_{1 - \alpha ,~2,{n_x}+{n_y} - 2}^2\) (Hotelling 1931). In this study, we have also tested the composite using |PC| <1STD criteria as contrast samples, and we found the results do not change (not shown in the following).

3 Contribution of North Atlantic water cycle to 2015 warm-season extreme precipitation

3.1 Atmospheric moisture flux during the 2015 extreme rainfall events

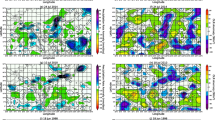

The 2015 extreme event is manifested in the seasonal mean precipitation (Fig. 1a, b). In the spring (MAM), significant above-normal precipitation is observed over the Central and Southern US (Fig. 1a). The increases in precipitation are most significant over Texas and Louisiana, where the 2015 MAM precipitation exceeds climatology by more than 2 mm day−1, equivalent to a 50% increase in the area-averaged seasonal-mean precipitation (Fig. 1a). In the summer, the positive precipitation anomalies in the Southern US weaken, but migrate northward to the US Midwest and the Great Lakes (Fig. 1b).

2015 US warm-season precipitation anomaly (colored, unit: mm day−1): a MAM, and b JJA. The hatched are the areas where the precipitation anomaly is significant at the 0.05 level; c–f are the atmospheric moisture flux anomaly in the 2015 MAM and JJA. In c–f, the colored areas show the anomalies of moisture flux divergence (unit: mm day−1). The vectors are the divergent component of moisture flux in c, d and are the full field of moisture flux anomaly in e, f (unit: kg m−1 s−1). Despite prevailing westerlies (e, f), US east coast dwellers are well aware that it is the east winds that bring in rain from the ocean (c, d)

The US precipitation anomalies in the 2015 spring and summer can be explained by the atmospheric MFD in the local atmospheric columns (Fig. 1c, d). In the spring, there are 2.5 mm day−1 increases in moisture flux convergence (MFC) in the Southern US corresponding to the observed 2 mm day−1 precipitation increase (Fig. 1c). Thus, the net moisture input from nonlocal sources is more than enough to sustain the extreme precipitation and can fully explain the observed precipitation anomaly. In the summer, the anomalous MFC moves northward, along with the excessive precipitation. The spatial distribution of the MFC anomaly generally follows the precipitation anomaly, except for the eastern portion of the Great Lakes (Fig. 1d). In these areas, the MFC anomaly (0.5–1 mm day−1) contributes approximately 30% of the observed precipitation anomaly (1.5–2 mm day−1), suggesting that local moisture recycling is a necessity to maintain the wet summer of 2015 (Fig. 1d).

The increased springtime MFC in the Southern US coincides with an increased moisture export from the subtropical North Atlantic (Fig. 1c, e). Examination of the divergent component of moisture flux suggests that the excessive moisture inflow into the Southern US comes mainly from two regions in the subtropical North Atlantic located along 40°N and the Southern edge of the subtropical oceans (15°–20°N) (Fig. 1c). Along 40°N, MFD increases by 2–2.5 mm day−1 in the spring of 2015. The excessive moisture from the subtropical North Atlantic tends to be transported into the Southern US (mostly Texas and Louisiana, the areas with maximum rainfall increases) along an intensified and westward movement of the subtropical high circulation (Fig. 1e), although the exact moisture transport pathway should be identified using a Lagrangian moisture tracking method. In addition, the anomalous MFD (2.5 mm day−1) over the Southern edge of the subtropical oceans contributes moisture to a relatively smaller area along the Gulf Coast (Fig. 1c).

In the summer, the MFD at 40°N is weakened or even reversed to MFC off the US coast. The largest oceanic moisture sources are located in the Southern portion of the subtropical oceans, where MFD anomalies exceed 3 mm day−1 and the divergent component of the moisture flux is directed to the Midwest. Thus, the excessive moisture for summer precipitation is from the climatological moisture source region for the Midwest (Gimeno et al. 2012). The results are consistent with our previous study about the seasonal evolution of precipitation across the Southern US and Midwest (Li et al. 2016b).

In contrast to the subtropical North Atlantic, the Pacific Ocean did not contribute a significant amount of moisture to the 2015 extreme precipitation. With the ongoing El Niño in the tropical Pacific, MFD increases in the subtropical oceans (Fig. 1c). The increased moisture flux from the subtropical North Pacific mainly converges in the tropical oceans (Fig. 1c), consistent with the typical circulation pattern induced by ENSO events (e.g., Seager et al. 2012; Xu et al. 2015). However, the moisture from the North Pacific barely converges onto the Southern US, indicating that the El Niño induced water cycle change does not directly influence the MFC that is a pre-requisite for the 2015 extreme precipitation event (Fig. 1c). Previous studies attributed the 2015 Southern US extreme rainfall to the atmospheric circulation change forced by the El Niño event (Wang et al. 2015). The analysis here suggests that the water cycle in the subtropical North Atlantic plays the dominant role in sustaining the moisture supply for the excessive precipitation, which together with the ENSO-induced circulation change fuels the 2015 extreme event (see details in Sect. 3.3).

3.2 The subtropical North Atlantic water cycle and its contribution to US precipitation

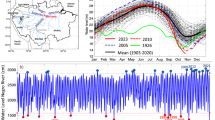

By performing a CEOF analysis, we show that warm-season extreme precipitation in 2015 is representative of a seasonal evolution mode of US precipitation throughout the historical records (1950–2015). Figure 2 shows the CEOF modes of spring and summer precipitation. The first CEOF mode shows a wet spring in the Southeastern US followed by a dry summer in the Central US (Fig. 2a, c). In contrast, the second CEOF mode is manifested as a northward movement of precipitation anomalies in the central US from spring to summer. In the spring, above normal precipitation is located in the Southern US (Fig. 2b). The excessive precipitation migrates northward to the Midwest in the summer. At the same time, dry summer conditions develop in the Southeastern US (Fig. 2d). The mode of variability presented in the second CEOF closely resembles the seasonal evolution of the 2015 warm-season precipitation (Fig. 1a, b). The PC2 index in 2015 exceeds two STD of the mode time series (Fig. 2f). Furthermore, the pattern correlation coefficients between 2015 spring (summer) precipitation anomaly and the CEOF-2 MAM (JJA) mode is 0.72 (0.41), both significant at a 0.001 level. It is worth noting that the similarity between the 2015 case and CEOF-2 is not solely caused by a disproportionate contribution from the 2015 case in generating the CEOF-2 mode. We computed the CEOF modes excluding the 2015 record and found that the spatial pattern and PC time series remain unchanged from those shown in Fig. 2. Similarly, the pattern correlation between 2015 case and the CEOF mode-2 is 0.68 and 0.39 for MAM and JJA, respectively.

The leading two CEOF modes of US warm season precipitation: a, b are the MAM mode and c, d JJA mode. The colors indicate where the projection of seasonal precipitation onto the mode index is significant at the 0.05 level. e, f are the normalized PC time series associated with the first and second CEOF mode. The red dots in e, f mark the year 1993, 2008 and 2015 with extreme summer precipitation in the US Midwest

The precipitation evolution pattern depicted by CEOF mode-2, and exemplified by the 2015 extreme event, seems to have become more dominant in recent decades. Figure 2f shows the PC of CEOF mode-2. According to our analysis, the STD of the PC increases by 68% (92%) in the 1986–2015 (1996–2015) compared to the 1950–1979 (1950–1969) period. This increase in CEOF2 mode variability indicates a stronger projection of the seasonal rainfall evolution pattern upon this northward migration mode (Fig. 2b, d). The mode variability increase is consistent with the increased frequency of both drought and flooding in the Southern US, as well as more variable summer rainfall in the Southeast (Wang et al. 2010a; Li et al. 2011; Wuebbles et al. 2014; Feng et al. 2016). Thus, extreme rainfall events, such as the 2015 case, are more likely to occur in recent decades than in the past. Given this context, a detailed analysis of the causes of CEOF mode-2 will provide insights for understanding extreme warm-season US precipitation.

Similar to the 2015 case, the variability of CEOF mode-2 is associated with the water cycle in the subtropical North Atlantic. Figure 3 shows the composite of springtime (MAM) and summertime (JJA) atmospheric moisture flux upon the PC2 time series. During the entire 1950–2015 period, above-normal spring precipitation in the Southern US coincides with an increased MFC in the local atmospheric column. The increased moisture inflow into the Southern US most likely originates from the northwestern portion of the subtropical North Atlantic (north of 20°N and west of 60°W), where MFD increases by 0.8–1 mm day−1 with PC2 exceeding one STD (Fig. 3a). The divergent component of moisture flux suggests that the excessive subtropical water is directed towards the Southern US and constitutes about 1 mm day−1 moisture input to the local area (Fig. 3a). In the summer, as the precipitation anomalies move northward, the MFC anomalies also migrate towards the Midwest. Accompanying the northward displacement of the MFC, the oceanic moisture sources shift westward and are located in the Gulf of Mexico (Fig. 3b). According to previous studies, the Gulf of Mexico is a climatological moisture source region for summer precipitation in the Midwest (Schubert et al. 2004; Gimeno et al. 2010, 2012). Thus, the JJA mode is likely caused by the intensified/weakened moisture flux in the source regions. Overall, the moisture budget analysis suggests an important contribution from the water cycle in the subtropical North Atlantic to the variability of CEOF mode 2, a seasonal evolution mode resembling the 2015 extreme rainfall event.

MAM (left column) and JJA (right column) atmospheric moisture flux anomalies composite on PC2 time series: a, b are 1950–2015 composite; c, d are 1950–1979 composite; and e, f are 1986–2015 composite. The colors show the MFD anomaly (unit: mm day−1), and the vectors are the anomaly of the divergent component of moisture flux (unit: kg m−1 s−1). MFD anomaly and the divergent component of moisture flux are shown only in the grid cells where MFD anomalies are significant at the 0.05 level by the student t test or the anomalies of the divergent component of moisture flux are significant at the 0.05 level by the Hotelling’s t-squared test

Since this mode of variability has significantly intensified in the second half of the record, we repeated the composite analysis for the 1950–1979 and 1986–2015 periods. According to the analysis, the most significant differences in the two moisture flux composites are located in the subtropical North Atlantic (Fig. 3c–f). In the 1950–1979 composite, there is almost no increase in MFD in the subtropical North Atlantic, especially in the spring (Fig. 3c, d). In the spring, along the northwestern portion of the subtropical ocean, the climatological MFD is weakened and shows an anomalous MFC, indicating that the subtropical ocean exports less moisture (Fig. 3c). As a result, there is no significant springtime MFC anomaly in the Southern US (Fig. 3c). In addition, the moderate wetting of the Midwest draws moisture mainly from the tropical Pacific (south of 15°N; Fig. 3d). The 1950–1979 composite suggests that the water cycle in the subtropical North Atlantic does not closely connect to the moisture balance over the conterminous US during this period. Such a connection between the oceanic and terrestrial water cycles becomes more significant in the recent 30 years of the record. In the 1986–2015 composite, springtime MFD in the northwestern portion of the subtropical North Atlantic exceeds 1.6 mm day−1, significant at a 0.05 level according to the student t test (Fig. 3e). The increased moisture export is directed toward the Southern US and significantly increases local MFC (Fig. 3e). Similar North Atlantic influence can be observed in the summer season. With an increase of MFD in the Gulf of Mexico by 1.8 mm day−1, more moisture is transported and converges in the Midwest, leading to excessive summer precipitation there (Fig. 3f).

The above analysis suggests that moisture from the subtropical North Atlantic is influencing the US moisture balance more significantly in recent decades. This enhanced Atlantic influence contributes to the recently increased variability of the CEOF mode-2 of US precipitation (Fig. 2f), which can be translated to an increased likelihood of extreme rainfall events, such as the 2015 case. Thus, in addition to the ENSO teleconnection identified in previous studies (Meehl and Teng 2007; Wang et al. 2015), the results here indicate that water cycle variability in the North Atlantic source regions can also fuel US extreme rainfall events during the warm season.

3.3 ENSO teleconnection and its relationship with the North Atlantic water cycle

In 2015, a strong El Niño event developed in the tropical Pacific. The ongoing El Niño induced an anomalous wave train in the mid-latitudes, which sets up a favorable background circulation for the extreme spring precipitation in the Southern US (Wang et al. 2015). Since the ENSO teleconnection is a major driver of US precipitation variability (e.g., Ropelewski and Halpert 1987; Higgins et al. 1997; Barlow et al. 2001), it is important to evaluate whether the contribution of the subtropical North Atlantic water cycle to the 2015 extreme US precipitation results from the covariability between ENSO and the water cycle.

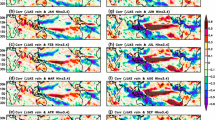

Thus, we analyzed the MAM and JJA moisture flux fields associated with El Niño events. Here, El Niño events were determined as years when MAM Niño 3.4 SST anomaly exceeds one STD. It is apparent from the composite shown in Fig. 4 that El Niño events are associated with anomalous MFC in the cold tongue which weakens the climatological MFD in this area. This leads to a reduction in moisture export from the local ocean (Fig. 4a). The ENSO’s impact on atmospheric moisture flux is most significant in the Pacific, and reflects a typical atmospheric teleconnection pattern, i.e., the Pacific-North-America (PNA) pattern (Alexander et al. 2002). In the North Atlantic, the anomalous MFC occurs in the Inter American Seas, whereas there is almost no change in MFD in the subtropical North Atlantic (Fig. 4a). The result is consistent with Castillo et al. (2014), whose moisture tracking analysis shows no significant changes in North Atlantic subtropical moisture sources during El Niño years.

Anomalies in MFD (colors; unit: mm day−1) and the divergent component of moisture flux (vectors; unit: kg m−1 s−1) composite on the Niño 3.4 index: a MAM composite; b JJA composite. The composite cases are the years with Niño 3.4 SSTA exceeds one STD. The divergent component of moisture flux is shown only for the grid cells where the MFD anomaly or the divergent component is significant at 0.05 level. c, d are the anomalies in MAM and JJA MFD (colors) and the divergent component of moisture flux (vectors) in 2015 resulting from a linear relationship with ENSO

In addition, the Southern US tends to experience less moisture input from external sources during El Niño years (Fig. 4a, b). Assuming a linear relationship between ENSO and MFD, Fig. 4b shows the anomalous MFD and the divergent component of moisture flux over the conterminous US given the 2015 El Niño intensity. Over the Southern US, the 2015 El Niño tends to reduce climatological MFC by 0.6 mm day−1, and should thus counteract the observed extreme precipitation (Fig. 4b). Overall, the ENSO composite moisture flux pattern in the North Atlantic and US sector differs from the 2015 case (Fig. 1a), as well as from that composite on CEOF mode-2 (Fig. 3a, e). Thus, the increased springtime moisture flux from the subtropical North Atlantic in 2015 is unlikely to have benefitted from the ongoing El Niño in the tropical Pacific.

Our analysis of summertime moisture flux, however, suggests that the ongoing El Niño might have positively contributed to the excessive precipitation in the US Midwest and the Great Lakes in 2015. According to Fig. 4c, in the summer following springtime El Niño, the peak of MFC anomaly shifts to the west of the dateline. MFC slightly increases in the US Midwest and the Great Lakes, contributing to approximately 0.2 mm day−1 above normal precipitation in the area (Fig. 4c, d). The positive contribution of El Niño to summertime Midwest precipitation is also noticed in previous studies (Ting and Wang 1997; Barlow et al. 2001; Schubert et al. 2004; Harding and Snyder 2015). The increase in MFC following the 2015 El Niño is equivalent to 20% of the total rainfall increase during the 2015 summer (Figs. 1b, 4d). Thus, the 2015 El Niño induced moisture flux variation plays a secondary but non-negligible role in the anomalous summer precipitation in the US, in addition to the water cycle in the subtropical North Atlantic.

4 Subtropical North Atlantic water cycle and its imprint on SSS

4.1 North Atlantic SSS precursor of 2015 US extreme precipitation events

The above analysis highlights the contributions of the North Atlantic water cycle to the CEOF mode-2 of US precipitation and the 2015 extreme precipitation event. The oceanic water cycle leaves an imprint on sea surface salinity (SSS), with increased net moisture export (i.e., MFD) corresponding to increased SSS (Schmitt 2008; Lagerloef et al. 2010a; Yu 2011; D’Addezio and Bingham 2014). Our study suggests that a saltier springtime subtropical North Atlantic coincides with an increased ocean-to-land moisture transport to the Southern US, and thus above-normal spring precipitation in the South followed by an anomalously wet summer in the Midwest (Li et al. 2016b). This seasonal evolution of US precipitation anomalies during the high SSS years is similar to the CEOF mode-2 and the 2015 case (Figs. 1a, b, 2b, d).

The significant correlation between SSS in the northwestern portion of the subtropical oceanFootnote 1 and the CEOF PC2 (R = 0.31, p < 0.02) supports the SSS-rainfall relationship identified in Li et al. (2016b). Furthermore, along with the extreme US precipitation in 2015, we observed increases in SSS over the subtropical North Atlantic (Fig. 5). Specifically, the most significant SSS anomalies (>0.5 unit of PSS-78) are located along the climatological P–E = 0 isoline, which defines the boundary of the subtropical oceans (Fig. 5). It is noteworthy that the SSS anomaly collocates well with the MFD anomalies (Figs. 1c, 5), where the increased net removal of moisture from the ocean surface leads to excessive salt flux into the ocean. The results are consistent with Yu (2011), who showed a predominance of freshwater flux (P–E) in modulating SSS variation in this area.

2015 MAM SSS anomalies in the subtropical North Atlantic (colors; unit: PSS-78). The contours are the MAM climatology of E–P (unit: mm day−1) and the bold contours are the E–P = 0 isoline. The vectors are the MAM climatology of the divergent component of MFD (unit: kg m−1 S−1). The hatched area denotes the northwestern portion of the subtropical North Atlantic.

The high salinity in the spring of 2015 provides independent evidence to support our previous study (Li et al. 2016b). In addition, the patterns of anomalous atmospheric moisture flux (Fig. 1c, d) and soil moisture content (Fig. 6) in 2015 are consistent with the physical mechanisms proposed in Li et al. (2016b), which is summarized and illustrated in Fig. 7.

Schematic figure illustrating the soil moisture mechanism bridging the 3-month time lag between springtime SSSA and summer precipitation in the US Midwest: in the western North Atlantic, higher springtime salinities are an indicator of enhanced moisture export onto the continental US which converges in the South. This greatly increases soil moisture there, allowing for enhanced evaporation and leading to more atmospheric convection on land (upper panel). The intensified convection on land draws in more moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and leads to the enhancement of the Great Plains Low Level Jet, which carries moisture to the upper Midwest in summer (bottom panel)

Initially, the increased moisture transport from ocean to land elevated soil moisture content in the Southern and Central US during the spring season. In the subsequent seasons, the high soil moisture content is preserved due to the 3–6-month land surface memory. The high soil moisture content serves as a moisture source to the local atmospheric column by increasing boundary layer humidity in the Southern and Central US. With the prevailing southerly wind in the summer, more moisture will be converged into the US Midwest, which is thermodynamically favorable for heavier precipitation (Meehl and Washington 1988; Delworth and Manabe 1989; Ek and Holtslag 2004).

In addition, the spatial distribution of soil moisture influences precipitation through atmospheric dynamics, i.e. the intensity of the Great Plains Low-level jet (GPLLJ). Specifically, the increased soil moisture in the Central US enhances the west-to-east soil moisture gradient along the slope of the Rocky Mountains. The soil moisture content gradient increases the zonal pressure gradient and forces the GPLLJ to intensify to balance the enhanced pressure gradient (Fast and McCorcle 1990, 1991). The intensified GPLLJ brings more Gulf of Mexico moisture northward, favors moisture flux convergence in the Midwest, and thus contributes to high precipitation dynamically.

The proposed mechanism is verified by the soil moisture content anomalies in the 2015 case (Fig. 6). Specifically, in the spring of 2015, the increased moisture inflow from the subtropical North Atlantic increases local soil moisture content in the Southern US. Both the NOAA CPC (model-based soil moisture product) and Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS; satellite remote-sensing soil moisture) datasets show anomalously high soil moisture content in the Southern US, especially along the coast of Texas where the extreme precipitation peaks (Fig. 6a, b). In the summer, soil moisture anomalies expand northward along with the seasonal strengthening of the GPLLJ (Fig. 6c, d). The increased soil moisture content in the Central US can influence the precipitation both thermodynamically and dynamically, and thus lead to above-normal precipitation in the US Midwest and Great Lakes [see details of the moisture budget analysis in Li et al. (2016b)]. The soil moisture anomalies in 2015 support the delay mechanism proposed in Li et al. (2016b) and Fig. 7, which bridges the 3-month lag of Midwest precipitation following springtime SSS in the northwestern subtropical North Atlantic. Thus, the 2015 case confirms our conclusion that salinity in the northwestern portion of the subtropical North Atlantic is indicative of US precipitation variability and can be a useful predictor for summer precipitation in the US Midwest.

4.2 Salinity as a predictor of historic Midwest extreme precipitation events

The SSS precursor observed in 2015 also appeared in the springs of 1993 and 2008, two other years with record-high summer precipitation in the US Midwest (Lott et al. 2012). Averaged over the Midwest (106–90°W, 37–49°N), precipitation anomalies exceed 4.3 and 1.3 standard deviations in the summer of 1993 and 2008, respectively. The extreme summer precipitation in these two years is preceded by wet springs in the Southern US (Fig. 8), presenting a seasonal rainfall evolution pattern similar to the second CEOF mode (Fig. 2b, d). Indeed, the 1993 and 2008 cases show high projection coefficients upon the CEOF mode-2 (Fig. 2f), a mode that is significantly influenced by the water cycle of the subtropical North Atlantic.

Since the water cycle provides a direct forcing on SSS variability in the subtropical oceans, the SSS precursor appeared in the subtropical North Atlantic in both springs, with above-normal SSS in the northwestern portion of the subtropical ocean (Fig. 9). Specifically, the maximum increases in SSS in 1993 are located off the eastern coast of the US, where positive SSS anomalies exceeds 0.8 unit of PSS-78 (Fig. 9a). In addition, the 2008 spring witnessed the most significant SSS increase in the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf Stream extension region, and the center of the subtropical gyre (Fig. 9b). Overall, the domain averaged SSS anomalies in the northwestern portion of the subtropical ocean are 0.15 (0.10) unit of PSS-78 in the spring of 1993 (2008), equivalent to 2.23 (1.49) standard deviation of SSS variation in this area (Fig. 9).

The lead time of salty subtropical North Atlantic in the spring to extremely wet summer in the Midwest suggests that SSS can be an indicator of extreme summer precipitation in the Midwest. Assuming a linear relationship between SSS and precipitation, the positive SSS anomaly in 1993 will be followed by a 0.7 mm day−1 increase in Midwest summer precipitation, which alone explains 37% of the observed precipitation anomalies. In contrast, the previously identified ENSO predictor (Mei and Wang 2011) can only explain 8%, insufficient to account for the observed 1993 extreme precipitation (Patricola et al. 2015). Furthermore, the SSS-based prediction forecasts 0.47 mm day−1 precipitation anomalies in the summer of 2008. The predicted precipitation equates to 78% of the observed precipitation anomaly. The higher-than-normal springtime subtropical North Atlantic SSS occurs in five out of six historical extreme precipitation events in the Midwest. Meanwhile, in all of the 6 years with the saltiest subtropical ocean, a wet summer ensued in the Midwest.

The success of using SSS in predicting extreme Midwest precipitation suggests that SSS can add important predictive skills to the existing SST-based seasonal forecast of terrestrial precipitation. Our previous study showed that SSS in the northwestern portion of the subtropical North Atlantic is a more important predictor for US Midwest summer precipitation in comparison with SST and atmospheric circulation modes (Li et al. 2016b). The superior rainfall predictive skill from SSS variations is even more apparent for extreme precipitation. Figure 10 shows the global SST anomaly (SSTA) in the spring and summer of 1993, 2008, and 2015. Among the three cases analyzed in this study, the SSTA patterns differ significantly. In 1993, the spring SSTA is characterized by a 1 K warming in the eastern tropical Pacific (Fig. 10a). The SSTA, however, almost completely decayed in the summer season when the extreme precipitation in the Midwest peaked (Fig. 10b). Such an SSTA pattern is favorable for wet summers in the Midwest and does contribute to the observed extreme events (Ting and Wang 1997; Weaver et al. 2009). The SSTA pattern in 2008 is almost opposite to the 1993 case, i.e. a cold Pacific but warm Atlantic (Fig. 10c, d). Previous studies suggested that a cold Pacific in combination with a warm Atlantic is favorable for drought in the US Midwest (Hoerling and Kumar 2003; McCabe et al. 2004; Schubert et al. 2004; Mo et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2010b). The development of the 2008 extreme events with the backdrop of the drought-prone SSTA pattern indicates that the seasonal forecasts of extreme Midwest summer seasons tend to be biased when only based on typical SSTA patterns. Similarly, the SSTA patterns in 2015 spring and summer show distinctly different structures compared to the 1993 and 2008 cases. With the 2015 El Niño event, positive SSTA spanned the central and eastern Pacific. The warm SSTA also extended to the Gulf of Alaska and the California Coast (Fig. 10e, f). Concurrent with the El Niño, a warming of the Indian Ocean by 1–1.5 K was seen (Fig. 10e, f). Such an anomalously warm Indian Ocean is absent in the 1993 and 2008 cases, which complicates the prediction of 2015 Midwest summer precipitation based on SSTA modes.

5 Discussions and conclusions

This study assesses the contribution of the oceanic water cycle to the extreme 2015 warm-season (MAM and JJA) precipitation event in the US. The record-breaking precipitation affected the Southern US in the spring and migrated northward to the Midwest and Great Lakes in the summer of 2015. Analysis of atmospheric moisture flux indicates that this extreme event is largely fueled by excessive moisture export from the subtropical North Atlantic. This North Atlantic contribution to 2015 US extreme precipitation differs from the typical changes in atmospheric moisture flux forced by ENSO variability. Thus, the influence of the North Atlantic water cycle on the extreme precipitation is independent of the impact exerted by the ongoing El Niño during the 2015 warm season.

The seasonal evolution of the precipitation in 2015 is representative of the second CEOF mode of US warm-season precipitation. Similar to the 2015 case, the rainfall variability depicted by the CEOF mode 2 is significantly influenced by the water cycle in the subtropical North Atlantic. Specifically, the excessive springtime precipitation in the Southern US is sustained by moisture from the northwestern portion of the subtropical North Atlantic. The oceanic moisture sources migrate into the Gulf of Mexico in the summer, which supplies moisture to above-normal summer precipitation in the Midwest and Great Lakes region.

Our analysis further showed that the interannual variability of the CEOF mode-2 has significantly intensified in the second half of the analysis period, suggesting that extreme precipitation events, like the 2015 case, are more likely to occur in recent decades. Indeed, both the 1993 and 2008 extreme precipitation events occur in the second half of the records and show anomalously high PC2 values. The intensified mode variability likely results from a stronger contribution of the subtropical North Atlantic water cycle to US precipitation (Gimeno et al. 2013).

Conservation of water and salt assures that the water cycle in the subtropical North Atlantic leaves an imprint on SSS. The close relationship between the subtropical water cycle and precipitation in the US makes subtropical SSS a useful predictor of summer precipitation in the US Midwest (Li et al. 2016b). The 2015 case provides independent evidence to support the predictability of Midwest precipitation based on springtime North Atlantic SSS. In the spring of 2015, abnormally high SSS is observed in the northwestern portion of the subtropical North Atlantic, which collocates with the increased moisture flux divergence. Furthermore, the changes in atmospheric moisture flux and land-surface variables in 2015 support the physical mechanisms proposed in our previous study (Li et al. 2016b).

By comparing the springtime SSS and SST patterns in the extreme cases (i.e. 1993, 2008, and 2015), we show that the SSS precursor, a saltier subtropical North Atlantic, appeared in all three spring seasons preceding the extreme events. In contrast, SST patterns were distinctly different among the three events. The SSS appears to be a more reliable predictor than SST in forecasting the summertime extreme precipitation in the US Midwest. Thus, our study calls for sustained monitoring of SSS using both in-situ and remote sensing tools (Lagerloef et al. 2010b), which will help to improve the predictability of extreme rainfall events.

Notes

The northwestern portion of the subtropical ocean is defined as the regions where local evaporation exceeds precipitation in the MAM and the divergent component of atmospheric moisture flux is directed northwestward towards the US continent (Li et al. 2016b).

References

Alexander MA, Bladé I, Newman M, Lanzante JR, Lau NC, Scott JD (2002) The atmospheric bridge: the influence of ENSO teleconnections on air–sea interaction over the global oceans. J Clim 15(16):2205–2231

Barlow M, Nigam S, Berbery EH (2001) ENSO, Pacific decadal variability, and US summertime precipitation, drought, and stream flow. J Clim 14:2105–2128

Bretherton C, Smith C, Wallace JM (1992) An intercomparison of methods for finding coupled patterns in climate data. J Clim 5:541–560

Castillo R, Nieto R, Drumond A, Gimeno L (2014) The role of the ENSO cycle in the modulation of moisture transport from major oceanic moisture sources. Water Resour Res 50:1046–1058

Chan SC, Misra V (2010) A diagnosis of the 1979–2005 extreme rainfall events in the Southeast US with isentropic moisture tracing. Mon Weather Rev 138:1172–1185

Chen T-C, Pfaendtner J (1993) On the atmospheric branch of the hydrological cycle. J Clim 6:161–167

D’Addezio JM, Bingham FM (2014) A subtropical North Atlantic regional atmospheric moisture budget. J Geophys Res Oceans 119:8731–8748

Dee DP et al (2011) The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Quart J R Meteorol Soc 137:553–597

Delworth T, Manabe S (1989) The influence of soil wetness on near-surface atmospheric variability. J Clim 2(12):1447–1462

Dirmeyer PA, Schlosser CA, Brubaker KL (2009) Precipitation, recycling, and land memory: an integrated analysis. J Hydrometeor 10:278–288

Ek MB, Holtslag AAM (2004) Influence of soil moisture on boundary layer cloud development. J Hydrometeor 5(1):86–99

Fast JD, McCorcle MD (1990) A two-dimensional numerical sensitivity study of the Great Plains low-level jet. Mon Weather Rev 118(1):151–164

Fast JD, McCorcle MD (1991) The effect of heterogeneous soil moisture on a summer baroclinic circulation in the central United States. Mon Weather Rev 119(9):2140–2167

Feng Z, Leung LR, Hagos S, Houze RA, Burleyson CD, Balaguru K (2016) More frequent intense and long-lived storms dominate the springtime trend in central US rainfall. Nat Commun 7:13429. doi:10.1038/ncomms13429

Gimeno L, Drumond A, Nieto R, Trigo RM, Stohl A (2010) On the origin of continental precipitation. Geophys Res Lett 37:L13804

Gimeno L et al (2012) Oceanic and terrestrial sources of continental precipitation. Rev Geophys 50:RG4003

Gimeno L, Nieto R, Drumond A, Castillo R, Trigo R (2013) Influence of the intensification of the major oceanic moisture sources on continental precipitation. Geophys Res Lett 40:1–8

Good SA, Martin MJ, Rayner NA (2013) EN4: quality controlled ocean temperature and salinity profiles and monthly objective analyses with uncertainty estimates. J Geophys Res Ocean 118:6704–6716

Harding KJ, Synder PK (2015) The relationship between the Pacific–North American teleconnection pattern, the Great Plains low-level jet, and North Central US heavy rainfall events. J Clim 28:6729–6742

Higgins RW, Yao Y, Yarosh ES, Janowiak JE, Mo KC (1997) Influence of the Great Plains low-level jet on summertime precipitation and moisture transport over the centural United States. J Clim 10:481–507

Higgins RW, Shi W, Yarosh E, Joyce R (2000): Improved United States precipitation quality control system and analysis, ATLAS No. 7. NCEP/Climate Prediction Center, Camp Springs, p 40

Higgins RW, Silva VBS, Shi W, Larson J (2007) Relationships between climate variability and fluctuations in daily precipitation over the United States. J Clim 20:3561–3579

Hoerling M, Kumar A (2003) The perfect ocean for drought. Science 299:691–694

Hotelling H (1931) The generalization of student’s ratio. Ann Math Stat 2:360–378

Kalnay E et al (1996) The NCEP-NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull Am Meteor Soc 77:437–471

Kanamitsu M, Ebisuzaki W, Woollen J, Yang S-K, Hnilo JJ, Fiorino M, Potter GL (2002) NCEP-DOE AMIP-II reanalysis (R-2). Bull Am Meteor Soc 83:1631–1643

Kobayashi S et al (2015) The JRA-55 reanalysis: general specifications and basic characteristics. J Meteor Soc Jpn 93:5–48

Koster RD et al (2004) Regions of strong coupling between soil moisture and precipitation. Science 305:1138–1140

Lagerloef G, Schmitt R, Schanze J, Kao H-Y (2010a) The oceans and the global water cycle. Oceanography 23(4):82–93

Lagerloef G, Boutin J, Carton J, Chao Y, Delcroix T, Font J, Lilly J, Reul N, Schmitt R, Riser S, Wentz F (2010b) Resolving the global surface salinity field and variations by blending satellite and in situ observations. In: Hall J, Harrison DE, Stammer D (eds) Proceedings of OceanObs’09: Sustained Ocean Observations and Information for Society (vol 2), Venice, ESA Publication WPP-306, pp 587–597

Li W, Li L, Fu R, Deng Y, Wang H (2011) Changes to the North Atlantic Subtropical High and its role in the intensification of summer rainfall variability in the Southeastern United States. J Clim 24:1499–1506

Li L, Li W, Barros AP (2013) Atmospheric moisture budget and its regulation of the summer precipitation variability over the Southeastern United States. Clim Dyn 41:613–631

Li L, Schmitt RW, Ummenhofer CC, Karnauskas KB (2016a) North Atlantic salinity as a predictor of Sahel rainfall. Sci Adv 2:e1501588. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501588

Li L, Schmitt RW, Ummenhofer CC, Karnauskas KB (2016b) Implications of North Atlantic sea surface salinity for summer precipitation over the US Midwest: mechanisms and predictive values. J Clim 29:3143–3159

Lott N, Smith A, Houston T, Shein K, Crouch J (2012) Billion dollar US weather/climate disasters 1980–2011. National Climate Data Center, Asheville, p 6

Lynch P (1988) Deducing the wind from vorticity and divergence. Mon Weather Rev 116:86–93

McCabe GJ, Palecki MA, Betancourt JL (2004) Pacific and Atlantic Ocean influence on multidecadal drought frequency in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101:4136–4141

Meehl GA, Washington WM (1988) A comparison of soil-moisture sensitivity in two global climate models. J Atmos Sci 45(9):1476–1492

Meehl GA, Teng H (2007) Multi-model changes in El Nino teleconnections over North America in a future warmer climate. Clim Dyn 29:779–790

Mei R, Wang G (2011) Impact of sea surface temperature and soil moisture on summer precipitation in the United States based on observational data. J Hydrometeor 12:1086–1099

Mignot J, Frankignoul C (2003) On the interannual variability of surface salinity in the Atlantic. Clim Dyn 20:555–565

Mo KC, J.-K. E. Schemm, Yoo S-H (2009) Influence of ENSO and the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation on drought over the United States. J Clim 22:5962–5982

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (2016) State of the climate: national overview for December 2015. http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/national/201512. Accessed 1 Nov 2016

Onogi K et al (2007) The JRA-25 reanalysis. J Meteor Soc Jpn 85:369–432

Patricola CM, Chang P, Saravanan R (2015) Impact of Atlantic SST and high frequency atmospheric variability on the 1993 and 2008 Midwest floods: regional climate model simulations of extreme climate events. Clim Change 129:397–411

Ropelewski CF, Halpert MS (1987) Global and regional scale precipitation patterns associated with the El Niño/Southern oscillation. Mon Weather Rev 115:1606–1626

Saha S et al (2006) The NCEP climate forecast system. J Clim 19:3483–3517

Schanze JJ, Schmitt RW, Yu LL (2010) The global oceanic freshwater cycle: A state-of-the-art quantification. J Mar Res 68:569–595

Schmitt RW (1995) The ocean component of the global water cycle. Rev Geophys 33:1395–1409

Schmitt RW (2008) Salinity and the global water cycle. Oceanography 21:12–19

Schmitt RW, Li L, Ummenhofer CC, Karnauskas KB (2015) Predicting Minnesota rainfall using Atlantic Ocean salinities. AMS 20th Conference on Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics, Minneapolis

Schubert SD, Suarez MJ, Pegion PJ, Koster RD, Bacmeister JT (2004) Causes of long-term drought in the US Great Plains. J Clim 17:485–503

Seager R, Naik N, Vogel L (2012) Does global warming cause intensified interannual hydroclimate variability? J Clim 25:3355–3372

Smith TM, Reynolds RW, Peterson TC, Lawrimore J (2008) Improvements to NOAA’s historical merged land-ocean surface temperature analysis (1880–2006). J Clim 21:2283–2296

Steinschneider S, Lall U (2016): El Nino and the US precipitation and floods: what was expected for the January–March 2016 winter hydroclimate that is now unfolding? Water Resour Res. doi:10.1002/2015WR018470.

Stohl A, James P (2004) A Lagrangian analysis of the atmospheric branch of the global water cycle. Part I: Method description, validation, and demonstration for the August 2002 flooding in Central Europe. J Hydrometeor 5:656–678

Ting M, Wang H (1997) Summertime US precipitation variability and its relation to Pacific sea surface temperature. J Clim 10:1853–1873

Trenberth KE, Dai A, Rasmussen RM, Parsons DB (2003) The changing character of precipitation. Bull Am Meteor Soc 84:1205–1217

Trenberth KE, Fasullo JT, Mackaro J (2011) Atmospheric moisture transports from ocean to land and global energy flows in reanalyses. J Clim 24:4907–4924

Uppala SM et al (2005) The ERA-40 re-analysis. Quart J R Meteor Soc 131:2961–3012

van der Ent RJ, Savenije HHG, Schaefli B, Steele-Dunne SC (2010) Origin and fate of atmospheric moisture over continents. Water Resour Res 46:W09525

Wang S-Y, Chen T-C (2009) The late-spring maximum of rainfall over the US Central Plains and the role of the low-level jet. J Clim 22:4696–4709

Wang H, Fu R, Kumar A, Li W (2010a) Intensification of summer rainfall variability in the Southeastern United States during recent decades. J Hydrometeor 11:1007–1018

Wang H, Schubert S, Suarez M, Koster R (2010b) The physical mechanisms by which the leading patterns of sst variability impact US precipitation. J Clim 23:1815–1836

Wang, S-YS, Huang W-R, Hsu H-H, Gillies RR (2015) Role of the strengthened El Nino teleconnection in the May 2015 floods over the southern Great Plains. Geophys Res Lett 42:8140–8146

Weare BC, Nasstrom JS (1982) Examples of extended empirical orthogonal function analysis. Mon Weather Rev 110:481–485

Weaver SJ, Schubert S, Wang H (2009) Warm season variations in the low-level circulation and precipitation over the central United States in observations, AMIP simulations, and idealized SST experiment. J Clim 22:5401–5420

Wu W, Dickinson RE, Wang H, Liu Y, Shaikh M (2007) Covariabilities of spring soil moisture and summertime United States precipitation in a climate simulation. Int J Climatol 27:429–438

Wu GX, Liu Y, Zhu X, Li W, Ren R, Duan A, Liang X (2009) Multi-scale forcing and the formation of subtropical desert and monsoon. Ann Geophys 27:3631–3644

Wuebbles D et al (2014) CMIP5 climate model analyses: climate extremes in the United States. Bull Am Meteor Soc 95:571–583

Xu G, Osborn T, Matthews AJ, Joshi MM (2015) Different atmospheric moisture divergence response to extreme and moderate El Niños. Clim Dyn. doi:10.1007/s00382-015-2844-2

Yu L (2011) A global relationship between the ocean water cycle and near-surface salinity. J Geophys Res Ocean 116:C10025

Acknowledgements

The authors thank three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. The data presented in this study can be obtained from public data archives. LL is supported by the Postdoctoral Scholar Program at WHOI, with funding provided by the Oceans and Climate Change Institute. RWS is supported by NASA Grants NNX12AF59G and NNX14AH38G, and NSF Grant OCE-1129646. CCU is supported by NSF Grant AGS-1355339.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L., Schmitt, R.W. & Ummenhofer, C.C. The role of the subtropical North Atlantic water cycle in recent US extreme precipitation events. Clim Dyn 50, 1291–1305 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3685-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3685-y