Abstract

No real-world data are available about the complications rate in drug-induced type 1 Brugada Syndrome (BrS) patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). Aim of our study is to compare the device-related complications, infections, and inappropriate therapies among drug-induced type 1 BrS patients with transvenous- ICD (TV-ICD) versus subcutaneous-ICD (S-ICD). Data for this study were sourced from the IBRYD (Italian BRugada sYnDrome) registry which includes 619 drug-induced type-1 BrS patients followed at 20 Italian tertiary referral hospitals. For the present analysis, we selected 258 consecutive BrS patients implanted with ICD. 198 patients (76.7%) received a TV-ICD, while 60 a S-ICD (23.4%). And were followed-up for a median time of 84.3 [46.5–147] months. ICD inappropriate therapies were experienced by 16 patients (6.2%). 14 patients (7.1%) in the TVICD group and 2 patients (3.3%) in S-ICD group (log-rank P = 0.64). ICD-related complications occurred in 31 patients (12%); 29 (14.6%) in TV-ICD group and 2 (3.3%) in S-ICD group (log-rank P = 0.41). ICD-related infections occurred in 10 patients (3.88%); 9 (4.5%) in TV-ICD group and 1 (1.8%) in S-ICD group (log-rank P = 0.80). After balancing for potential confounders using the propensity score matching technique, no differences were found in terms of clinical outcomes between the two groups. In a real-world setting of drug-induced type-1 BrS patients with ICD, no significant differences in inappropriate ICD therapies, device-related complications, and infections were shown among S-ICD vs TV-ICD. However, a reduction in lead-related complications was observed in the S-ICD group. In conclusion, our evidence suggests that S-ICD is at least non-inferior to TV-ICD in this population and may also reduce the risk of lead-related complications which can expose the patients to the necessity of lead extractions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

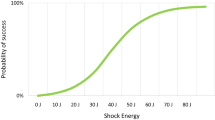

The sudden cardiac death (SCD) risk stratification of Brugada syndrome (BrS) patients is still challenging, in particular among those with a drug-induced type I electrocardiographic (ECG) pattern [1, 2]; in this subgroup, the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implantation for primary SCD prevention may be considered only in case of inducible ventricular fibrillation (VF) during programmed electrical stimulation at the electrophysiological study (EPS) [3]. The transvenous ICD (TV-ICD) implantation was frequently associated with complications among BrS patients, including inappropriate shocks (IAS), device or lead malfunctions, and infections[4,5,6]. Moreover, IAS was frequent in BrS patients with a subcutaneous ICD (S-ICD)[7]. However, these evidences refer to study cohort including more likely BrS patients with spontaneous ECG pattern and no data are available about the complications rate among drug-induced BrS patients implanted with TV-ICD or S-ICD. This study aimed to compare the device-related complications and inappropriate shocks among drug-induced BrS patients with TV-ICD versus S-ICD.

Materials and methods

Database

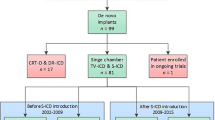

Data for this study were sourced from the IBRYD (Italian BRugada sYnDrome) registry which includes 619 drug-induced type-1 BrS patients followed at 20 tertiary referral hospitals throughout the Italian territory. All patients were diagnosed from July 1997 to May 2021, while follow-up was censored in December 2021. For the present analysis, we selected 262 consecutive BrS patients implanted with both subcutaneous (S-ICD Group) and transvenous (TV-ICD Group). From 2015, all participating hospitals have started to routinely implant S-ICD for primary prevention of SCD in young BrS patients not in need of pacing. Patients with incomplete baseline (n: 3) or follow-up data (n: 1) were excluded. The local institutional review boards approved the study (ID 553–19), and all patients provided written informed consent for data storage and analysis.

Diagnosis and EPS study protocol

BrS diagnosis was performed by inducing a type 1 ECG pattern through a flecainide or ajmaline drug test in all patients. Flecainide (2 mg/kg) was administered over 10 min, while Ajmalina (1 mg/kg) was administered over 5 min. The test was considered positive only if a coved type I ECG was documented in at least 1 of the right precordial leads (V1, V2), placed at the second, third, or fourth intercostal space. The EPS protocol consisted of double stimulation, at the apex and at the right ventricular outflow tract, of 2 drives (600 and 400 ms) and up to 3 extrastimuli by decreasing the coupling interval until inducing sustained ventricular arrhythmias, reaching chamber refractoriness, or a minimal coupling interval of 200 ms. The stimulation protocol was discontinued if VF or sustained (30 s)/syncopal polymorphic VT were induced.

ICD programming

The programming of the parameters for the detection of VT/VF was done according to the guidelines’ recommendations at the time of implant and optimized during the follow-up.

Until 2007, TV-ICDs were programmed with a VT window (cut-off rate 180–220 bpm) and/or a single VF zone (cut-off rate ≥ 220 bpm). From 2007, a single VF detection zone (cut-off rate 222–250 bpm) and a maximum of 6 shocks were programmed. S-ICD devices were programmed with a conditional zone, between 200 and 250 bpm, and a shock zone > 250 bpm.

Endpoints

The primary study endpoints were: ICD inappropriate therapies, defined as anti-tachycardia pacing (ATP) and/or shocks for conditions other than ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF); ICD-related complications, defined as all pulse generator (PG) or lead-related complications requiring surgical intervention; ICD-related infections, defined as all systemic infections requiring complete removal of thesystem including the leads extraction. Moreover, the type and distribution of ICD-related complications, defined as early, if occurred within 30 days after ICD implantation, or late, if occurred later than 30 days after implantation, were assessed. The secondary endpoint was all-cause mortality and appropriate ICD therapies.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were expressed as number and percentage, whereas continuous variables were expressed as either median [interquartile range (IQR)] or mean ± SD, based on their distribution as assessed both by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and the Shapiro–Wilk tests. Between-group differences, for categorical variables, were assessed by the chi-square test, with the application of Yates correction where appropriate. Either parametric Student’s t-test or nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test and Wilcoxon test were instead used to compare continuous variables, according to their distribution. The nearest neighbor propensity score matching (PSM) method, with a 1:1 ratio, without replacement, and with the use of a caliper (0.25-SD distance tolerance), was used to minimize the differences in baseline characteristics between patients receiving S-ICD vs TV-ICD group. Covariates included in the model were those significantly different between the 2 groups (age, history of syncope, and alcohol abuse).

Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed to assess the risk of primary outcome events either in the whole population (unadjusted) or in the matched cohorts (adjusted). A time-dependent Cox univariable (unadjusted) and multivariable (adjusted) regression model was used to evaluate the association between S-ICD and clinical outcome events. The multivariable model was computed on all covariates with a p-value < 0.05. A 2-sided probability p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (version 24.0, SPSS, Chicago, Illinois) and STATA 14.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Study population

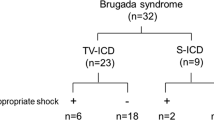

258 drug-induced BrS patients (mean age 51 ± 15; male 76.4%) with both TV-ICD (n: 198, 76.7%) and S-ICD (n: 60, 23.4%) followed for a median follow-up of 84.3 [46.5–147] months were included in the study. The indication for ICD implantation was primary prevention in 253 patients (98.1%) and secondary prevention in 5 patients (1.9%). TV-ICD was single or dual chambers in 187 (72.5%) and 10 patients (17.5%), respectively. S-ICD group showed more likely younger age (44 ± 12 vs 53 ± 15 years; P < 0.0001), lower prevalence of history of both syncope (40 vs 58.5%; P = 0.012), documented atrial tachyarrhythmias (1.7 vs 9.6%; P = 0.045) and alcohol abuse (0 vs 6.5%; P = 0.04) compared to TV-ICD group; moreover S-ICD group was followed for less time (46.3 [15.5–71] vs 111 [60.6–160]; P < 0.0001). Among TV-ICD patients, 61 patients (mean age 56.4 ± 14.2; male 72.1%) were implanted before 2007 and 131 (mean age 51.9 ± 14.99; male 77.4%) after 2007; no significant difference in baseline clinical characteristics was shown between the two groups. After PSM, 120 patients with balanced baseline characteristics were identified; all patients were implanted with single-lead ICD for primary prevention. All baseline clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Clinical outcome

The primary outcome events, divided into S-ICD vs TV-ICD subgroup are reported in Table 2.

Inappropriate ICD therapies

In the entire population, ICD inappropriate therapies were experienced by 16 patients (6.2%). 14 patients (7.1%) in the TV-ICD group and 2 patients (3.3%) in S-ICD group (P = 0.06). In all cases, the inappropriate ICD therapies were ICD shocks. The annual incident rate of ICD inappropriate therapies was 0.6%. The Kaplan–Meier analysis did not show a significantly different risk of inappropriate ICD therapies between the TV-ICD group implanted before and after 2007 (log-rank P = 0.60). At Cox univariable analysis no baseline patients’ characteristic, including the S-ICD (OR: 0.99; 95% CI 0.22- 4.06; P = 0.99) and the ICD implantation before 2007 (OR: 0.75; 95% CI 0.26- 2.2; P = 0.60) was associated with inappropriate ICD therapies.

In the matched cohort, ICD inappropriate therapies were experienced by 3 patients (2.5%). 2 patients (3.3%) in the S-ICD group, and 2 patient (3.3%) in the TV-ICD group (P = 0.986). At Cox univariable analysis no baseline patients’ characteristic, including the S-ICD (OR: 1.19; 95% CI 0.17–8.6; P = 0.86), was associated with inappropriate ICD therapies.The Kaplan–Meier analysis did not show a significantly different risk of inappropriate ICD therapies between the two subgroups in both unmatched (log-rank P = 0.64) and matched (log-rank P = 0.86) cohorts (Fig. 1).

ICD-related complications

ICD-related complications in need of surgical revision occurred in 31 patients (12%); 29 (14.6%) in TV-ICD group and 2 (3.3%) in S-ICD group (P = 0.018); mainly due to increased lead-related complications in TV-ICD vs S-ICD group (14.6% vs3.3%; P = 0.025). In contrast, no significant differences were shown in PG-related complications between the two subgroups (3.5% vs 1.7%; P = 0.46). The annual incident rate of ICD-related complications was 1.6%. At Cox univariate analysis no baseline patients’ characteristics, including the S-ICD (OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.12- 2.2; P = 0.39), was associated with ICD-related complications.

In the matched cohort, ICD-related complications in need of surgical revision occurred in 13 patients (10.8%); 11 (18.3%) in TV-ICD group and 2 (3.33%) in S-ICD group (P = 0.008); mainly due to increased lead-related complications in TV-ICD vs S-ICD group (15% vs1.7%; P = 0.008).

At Cox univariate analysis no baseline patients’ characteristic, including the S-ICD (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.27–1.99; P = 0.55), was associated with ICD-related complications. The Kaplan–Meier analysis did not show a significantly different risk of ICD complications between the two subgroups in both unmatched (log-rank P = 0.41) and matched (log-rank P = 0.09) cohorts (Fig. 2).

ICD-related infections

ICD-related infections in need of leads extraction occurred in 10 patients (3.88%); 9 (4.5%) in TV-ICD group and 1 (1.8%) in S-ICD group (P = 0.31).The annual incident rate of ICD-related infections was 0.44%.At Cox univariate analysis, no baseline patients’ characteristic, including the S-ICD (OR: 0.35; 95% CI 0.037–3.22; P = 0.55), was significantly associated with ICD-related infections.

In the matched cohort, ICD-related infections occurred in 5 patients (4.16%); 4 (6.6%) in the TV-ICD group, and 1 (1.66%) in the S-ICD group (P = 0.166). At Cox univariate analysis, the ICD replacement was the only independent predictor of ICD-related infectious (OR: 2.21; 95% CI 1.22- 4.01; P = 0.02). The Kaplan–Meier analysis did not show a significantly different risk of ICD-related infections between the 2 subgroups in both matched (log rank P = 0.80) and unmatched (log rank P = 0.33) cohorts (Fig. 3).

All-cause mortality and appropriate ICD therapies

5 (1.9%) patients died during follow-up, all in the TV-ICD subgroup. The annual incident rate of mortality was 0.33%0.13 (5%) patients experienced appropriate ICD therapies, all in the TV-ICD subgroup. The annual incident rate of appropriate ICD therapies was 0.32%.

Discussion

The main results of our study are the following: among drug-induced BrS patients no significant differences in inappropriate ICD therapies and ICD-related complications and infections were shown between TV-ICD vs S-ICD group; S-ICD was characterized by a lower rate of lead-related complications leading to surgical revision or extraction; no patients’ clinical features were associated to ICD inappropriate shocks or complications.The overall incidence of inappropriate ICD therapies among our cohort of drug-induced BrS patients was about 6.2% over a median follow-up of 83.7 months, three times lower than that emerged from a recent systematic review including 11 studies and 750 BrS patients, of whom 53.4% with drug-induced type-1 BrS, followed for 82.3 months [4]. Moreover, the annual incidence rate of inappropriate ICD therapies among our study population was 0.6%, 5 times lower than that emerged (3.3%) from a metanalysis of 22 studies including 1539 BrS patients with ICD, of whom 49% with drug-induced type-1 BrS [8].

The different incidence of ICD inappropriate therapies among our study population might be explained by different factors: first, our study cohort was composed of only drug-induced BrS patients. Considering that the presence of a spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern is one of the main causes of inappropriate shock among S-ICD patients [7], the exclusion of these patients from our study reduces this risk. We cannot exclude the probability of intermittent type 1 pattern, even if no specific triggers, such as fever or drug administration, were reported. Moreover, the introduction of an additional high-pass filter to the S-ICD sensing methodology [9], the enhanced supraventricular tachycardia discriminators [10], the activation of lead noise reduction algorithms [11], and the TV-ICD programming based on VF-only zone [12] with a cut-off rate greater than 220–240 bpm [13] and longer detection intervals [14] may have further reduced the risk of inappropriate ICD therapies.

The main causes of the inappropriate ICD therapies in our study cohort were the misdetection of supraventricular arrhythmias, mainly AF, in the TV-ICD group and the oversensing due to air entrapment in the S-ICD group. This latter evidence underlines the need to perform a systematic approach including device interrogation, provocative maneuvers, and chest radiography to early detect this early complication and an uncommon cause of IAS in S-ICD recipients [15].

Regarding the ICD-related complications, we observed an overall incidence of 12% over a median follow-up of 83.7 months, mainly lead-related, with an annual incident rate of 1.6%, as previously shown[8].

Among our study population, we showed lower ICD-related complications in S-ICD compared to TV-ICD recipients, mainly driven by less frequent lead-related complications; in contrast, no significant difference in device-related complications was shown between the 2 groups. These results confirm also in drug-induced type-1 BrS patients the emerging evidence from recent observational studies [16, 17].

Considering the young age of BrS patients, the reduction in lead-related complications represents a not negligible factor to consider in favor of the S-ICD implantation among this subgroup. Lead extraction is indeed one of the most hazardous electrophysiological procedures, accounting for risk of major complication rate of about 1.7%, including mortality of 0.5% [18]. The possibility to avoid transvenous lead implantation removes the risk of this type of complication.

Among our population, we reported a low rate of ICD infections, confirming the reduced number of infections in high implantation volume centers [19, 20]. This result may be due to the low prevalence of patients’risk factors for CIED infections, such as medical comorbidities, and the use of single-lead TV-ICD. Different from previous evidence [16, 17], no significant difference in ICD infections was shown between the TV-ICD and S-ICD groups. This evidence is of pivotal importance since systemic infections represent an important predictor of death for all causes, regardless of the result of the extraction procedure [21]. The only variable significantly associated with increased ICD-related infections in our population was the ICD replacement, as previously shown in the general population [22]. Moreover, it should be noted that the significant difference in the median follow-up duration among the two groups, 111 months in TV-ICD vs 46.3 months in S-ICD, might have underestimated the advantages of S-ICD. Looking at the Kaplan–Meier curves of all the outcomes, a clear separation between the two groups is evident, but a significant difference was not reached due to the low number of events and the shorter follow-up in the S-ICD group. This stresses the need of a longer follow-up which may help in better comprehending the long-term issue in this particular subgroup of Brugada patients.In light of all the above, our results support the hypothesis that S-ICD is at least not inferior to TV-ICD in drug-induced type-1 BrS patients; moreover, it offers an additive advantage in reducing the lead-related complications.

Limitations

The retrospective nature and non-randomized comparison are certain a limitation. However, the present study was the first including exclusively patients with drug-induced BrS who underwent S-ICD and TV-ICD implantation. The significant difference in the follow-up time between the two groups and the low number of outcome events may havei nfluenced the significatively of our results. Indeed, a bias could derive from the differences between groups and specifically from factors influencing the operator's decision to implant S-ICD or TV-ICD. Finally, the large time frame in which TV-ICD patients were implanted could itself be a bias, as, there have been changes in device programming after 2007 to reduce the frequency of inappropriate therapies [23, 24].

Conclusions

In a real-world setting of drug-induced type-1 BrS patients with ICD, no significant differences in inappropriate ICD therapies, device-related complications, and infections were shown among S-ICD vs TV-ICD. On the other hand, a reduction in lead-related complications was observed in the S-ICD group. Our evidence suggests that S-ICD is at least non-inferior to TV-ICD in this population and may also reduce the risk of lead-related complications which can expose the patients to the necessity of lead extractions.

Change history

06 January 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-022-02228-3

References

Krahn AD, Behr ER, Hamilton R, Probst V, Laksman Z, Han HC (2022) Brugada syndrome. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 8(3):386–405

Russo V, Pafundi PC, Caturano A, Dendramis G, Ghidini AO, Santobuono VE, Sciarra L, Notarstefano P, Rucco MA, Attena E, Floris R, Romeo E, Sarubbi B, Nigro G, D’Onofrio A, Calò L, Nesti M (2021) Electrophysiological study prognostic value and long-term outcome in drug-induced type 1 Brugada syndrome: the IBRYD study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 7(10):1264–1273

Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, Elliott PM, Fitzsimons D, Hatala R, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen K, Kuck KH, Hernandez-Madrid A, Nikolaou N, Norekvål TM, Spaulding C, Van Veldhuisen DJ (2015) 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: the task force for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death of the european society of cardiology (ESC)endorsed by: association for european paediatric and congenital cardiology (AEPC). Europace 17(11):1601–1687

El-Battrawy I, Roterberg G, Liebe V, Ansari U, Lang S, Zhou X, Borggrefe M, Akin I (2019) Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in Brugada syndrome: Long-term follow-up. Clin Cardiol 42(10):958–965

Conte G, Sieira J, Ciconte G, de Asmundis C, Chierchia GB, Baltogiannis G, Di Giovanni G, La Meir M, Wellens F, Czapla J, Wauters K, Levinstein M, Saitoh Y, Irfan G, Julià J, Pappaert G, Brugada P (2015) Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in Brugada syndrome: a 20-year single-center experience. J Am Coll Cardiol 65:879–888

Lee S, Li KHC, Zhou J, Leung KSK, Lai RWC, Li G, Liu T, Letsas KP, Mok NS, Zhang Q, Tse G (2020) Outcomes in Brugada syndrome patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: insights from the SGLT2 registry. Front Physiol 11:204

Casu G, Silva E, Bisbal F, Viola G, Merella P, Lorenzoni G, Motta G, Bandino S, Berne P (2021) Predictors of inappropriate shock in Brugada syndrome patients with a subcutaneous implantable cardiac defibrillator. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 32(6):1704–1711

Dereci A, Yap SC, Schinkel AFL (2019) Meta-analysis of clinical outcome after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation in patients with Brugada syndrome. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 5(2):141–148

Theuns DAMJ, Brouwer TF, Jones PW, Allavatam V, Donnelley S, Auricchio A, Knops RE, Burke MC (2018) Prospective blinded evaluation of a novel sensing methodology designed to reduce inappropriate shocks by the subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm 15(10):1515–1522

Geller JC, Wöhrle A, Busch M, Elsässer A, Kleemann T, Birkenhauer F, Bramlage P, Veltmann C, Investigators ReduceIT (2021) Reduction of inappropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapies using enhanced supraventricular tachycardia discriminators: the reduceit study. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 61(2):339–348

Beau S, Greer S, Ellis CR, Keeney J, Asopa S, Arnold E, Fischer A (2016) Performance of an ICD algorithm to detect lead noise and reduce inappropriate shocks. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 45:225–232

Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, Cho Y, Behr ER, Berul C, Blom N, Brugada J, Chiang CE, Huikuri H, Kannankeril P, Krahn A, Leenhardt A, Moss A, Schwartz PJ, Shimizu W, Tomaselli G, Tracy C (2013) Executive summary: HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes. Heart Rhythm 10(12):e85-108

Clementy N, Challal F, Marijon E, Boveda S, Defaye P, Leclercq C, Deharo JC, Sadoul N, Klug D, Piot O, Gras D, Bordachar P, Algalarrondo V, Fauchier L, Babuty D, Investigators DAI-PP (2017) Very high rate programming in primary prevention patients with reduced ejection fraction implanted with a defibrillator: results from a large multicenter controlled study. Heart Rhythm 14:211–217

Kutyifa V, Daubert JP, Schuger C, Goldenberg I, Klein H, Aktas MK, McNitt S, Stockburger M, Merkely B, Zareba W, Moss AJ (2016) Novel ICD programming and inappropriate ICD therapy in CRT-D vs ICD patients: a MADIT-RIT sub-study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 9(1):e001965

Iavarone M, Russo V (2022) Air entrapment as cause of S-ICD inappropriate shock. Heart Rhythm 19(10):1751–1752

Knops RE, Olde Nordkamp LRA, Delnoy PHM, Boersma LVA, Kuschyk J, El-Chami MF, Bonnemeier H, Behr ER, Brouwer TF, Kääb S, Mittal S, Quast ABE, Smeding L, van der Stuijt W, de Weger A, de Wilde KC, Bijsterveld NR, Richter S, Brouwer MA, de Groot JR, Kooiman KM, Lambiase PD, Neuzil P, Vernooy K, Alings M, Betts TR, Bracke FALE, Burke MC, de Jong JSSG, Wright DJ, Tijssen JGP, Wilde AAM, Investigators PRAETORIAN (2020) Subcutaneous or transvenous defibrillator therapy. N Engl J Med 383:526–536

Russo V, Rago A, Ruggiero V, Cavaliere F, Bianchi V, Ammendola E, Papa AA, Tavoletta V, De Vivo S, Golino P, D’Onofrio A, Nigro G (2022) Device-related complications and inappropriate therapies among subcutaneous vs transvenous implantable defibrillator recipients: insight monaldi rhythm registry. Front Cardiovasc Med 9:879918

Bongiorni MG, Kennergren C, Butter C, Deharo JC, Kutarski A, Rinaldi CA, Romano SL, Maggioni AP, Andarala M, Auricchio A, Kuck KH, Blomström-Lundqvist C, ELECTRa Investigators, (2017) The European lead extraction controlled (ELECTRa) study: a European heart rhythm association (EHRA) registry of transvenous lead extraction outcomes. Eur Heart J38(40):2995–3005

Tarakji KG, Mittal S, Kennergren C, Corey R, Poole JE, Schloss E, Gallastegui J, Pickett RA, Evonich R, Philippon F, McComb JM, Roark SF, Sorrentino D, Sholevar D, Cronin E, Berman B, Riggio D, Biffi M, Khan H, Silver MT, Collier J, Eldadah Z, Wright DJ, Lande JD, Lexcen DR, Cheng A, Wilkoff BL, Investigators WRAP-IT (2019) Antibacterial envelope to prevent cardiac implantable device infection. N Engl J Med 380(20):1895–1905

Russo V, Viani S, Migliore F, Nigro G, Biffi M, Tola G, Bisignani G, Dello Russo A, Sartori P, Rordorf R, Ottaviano L, Perego GB, Checchi L, Segreti L, Bertaglia E, Lovecchio M, Valsecchi S, Bongiorni MG (2021) Lead abandonment and subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (S-ICD) implantation in a cohort of patients with icd lead malfunction. Front Cardiovasc Med 8:692943

Tarakji KG, Wazni OM, Harb S, Hsu A, Saliba W, Wilkoff BL (2014) Risk factors for 1-year mortality among patients with cardiac implantable electronic device infection undergoing transvenous lead extraction: the impact of the infection type and the presence of vegetation on survival. Europace 16:1490–1495

Polyzos KA, Konstantelias AA, Falagas ME (2015) Risk factors for cardiac implantable electronic device infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 17(5):767–777

Sacher F, Probst V, Iesaka Y, Jacon P, Laborderie J, Mizon-Gérard F, Mabo P, Reuter S, Lamaison D, Takahashi Y, O’Neill MD, Garrigue S, Pierre B, Jaïs P, Pasquié JL, Hocini M, Salvador-Mazenq M, Nogami A, Amiel A, Defaye P, Bordachar P, Boveda S, Maury P, Klug D, Babuty D, Haïssaguerre M, Mansourati J, Clémenty J, Le Marec H (2006) Outcome after implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: a multicenter study. Circulation 114(22):2317–2324

Sacher F, Probst V, Maury P, Babuty D, Mansourati J, Komatsu Y, Marquie C, Rosa A, Diallo A, Cassagneau R, Loizeau C, Martins R, Field ME, Derval N, Miyazaki S, Denis A, Nogami A, Ritter P, Gourraud JB, Ploux S, Rollin A, Zemmoura A, Lamaison D, Bordachar P, Pierre B, Jaïs P, Pasquié JL, Hocini M, Legal F, Defaye P, Boveda S, Iesaka Y, Mabo P, Haïssaguerre M (2013) Outcome after implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: a multicenter study-part 2. Circulation 128(16):1739–1747

Acknowledgements

IBRYD study group: Vincenzo Russo, Gerardo Nigro (University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Department of MedicalTranslational Sciences, Division of Cardiology, Monaldi Hospital, Naples, Italy); Alfredo Caturano, Ferdinando Carlo Sasso (University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Department of Advanced Medical and Surgical Sciences, Piazza Luigi Miraglia 2, IT-80138 Naples, Italy), Federico Guerra (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Ospedali Riuniti, Ancona, Ancona, Italy); Federico Migliore (Università degli Studi di Padova, Padua, Italy); Giuseppe Mascia, Luca Barca, Italo Porto (IRCCS San Martino Polyclinic Hospital, Genoa, Italy); Andrea Rossi (Gabriele Monasterio Foundation, Pisa, Italy); Martina Nesti, Pasquale Notarstefano (Cardiovascular and Neurological Department, Ospedale San Donato, Via Nenni, 20/22, Arezzo 52100, Italy); Vincenzo Ezio Santobuono (University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine and Policlinico of Bari, Cardiology Unit, Italy); Emilio Attena, Maria Antonietta Ruocco (Cardiology Unit, Roccadaspide Hospital, ASL Salerno); Gianfranco Tola (Azienda Ospedaliera Brotzu, Cagliari, Italy); Luigi Sciarra, Leonardo Calò (Policlinico Casilino, Cardiology Unit, Rome, Italy); Giulio Conte, Livia Pardo Franchetti (Cardiocentro Ticino Foundation, Lugano, Switzerland); Alessandro Paoletti Perini (Azienda Sanitaria di Firenze, Florence, Italy); Pietro Francia, Carmen Adducci (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Sant'Andrea, Rome, Italy); Gregory Dendramis (Cardiology Unit, Clinical and Interventional Arrhythmology, ARNAS, Ospedale Civico Di Cristina Benfratelli, Palermo, Italy), Zeferino Palamà (Casa di Cura Villa Verde, Taranto, Italy); Stefano Albani, Nicola Berlier (Umberto Parini Regional Hospital, Aosta, Italy); Andrea Ottonelli Ghidini (Versilia Hospital, Cardiology Unit, Lido di Camaiore, Italy); Antonio D’Onofrio, Berardo Sarubbi (Monaldi Hospital, Departmental Unit of Electrophysiology, Evaluation and Treatment of Arrhythmias, Naples, Italy); Enrico Baldi, Alessandro Vicentini (IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy); Roberto Floris (Clinical Cardiology, Department of Medical Sciences and Public Health, University of Cagliari, Italy), Emanuele Romeo, Paolo Golino (Department of Cardiology, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Monaldi Hospital, Naples, Italy).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Russo, V., Caturano, A., Guerra, F. et al. Subcutaneous versus transvenous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator among drug-induced type-1 ECG pattern Brugada syndrome: a propensity score matching analysis from IBRYD study. Heart Vessels 38, 680–688 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-022-02204-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-022-02204-x