Abstract

Following the seminal contribution of Koray and Yildiz (J Econ Theory 176:479–502, 2018), we re-examine the classical questions of implementation theory under complete information in a setting where coalitions are fundamental behavioral units, and the outcomes of their interactions are predicted by applying the solution concept of the strong core. The planner’s exercise includes designing a code of rights that specifies the collection of coalitions having the right to block one outcome by moving to another. We provide a complete characterization of the implementable social choice rules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The challenge of implementation lies in designing a mechanism (i.e., a game form) in which the equilibrium behavior of agents always coincides with the recommendation given by a social choice rule (SCR). If such a mechanism exists, the SCR is implementable. Most early studies of implementation focused on noncooperative solution concepts, such as the Nash equilibrium (Maskin 1999) and its refinements (e.g., Moore and Repullo 1988; Abreu and Sen 1990).

Although implementation theory has had a tremendous success in identifying the class of SCRs that are implementable in various information structures, a nagging criticism of the theory is that many of its constructive proofs rely on questionable tail-chasing procedures to eliminate unwanted equilibria, such as integer or modulo games (Jackson 1992).Footnote 1

Since the relevance of the theory depends on the qualities of the devised mechanisms, economists have also been interested in understanding how to circumvent the limitations imposed by such unnatural features by exploring the possibilities offered by approximate (as opposed to exact) implementation (Abreu and Matsushima 1992), as well as by implementation by bounded mechanisms (Jackson 1992; Mukherjee et al. 2019). One additional way around those limitations is offered by implementation by codes of rights, recently proposed by Koray and Yildiz (2018).

As demonstrated in the seminal paper by Koray and Yildiz (2018), an alternative to the noncooperative approach is to allow groups of agents to coordinate their behaviors in a mutually beneficial manner. To move away from non-cooperative modeling, the details of coalition formation are left unspecified. Consequently, coalitions—not individuals—become the basic decision-making units. Here, the role of the solution concept is to explain why, when, and which coalition forms and what it can achieve.

More importantly, the chosen coalitional solution concept is independent of the physical structure under which coalition formation takes place (e.g., Chwe 1994). This structure, often defined by an effectivity relationship, specifies which coalitions can form given a status quo outcome, and what they can achieve when they form (i.e., what new status quo outcomes they can induce). From an implementation viewpoint, the effectivity relationship is the design variable, playing the role of the mechanism.

Koray and Yildiz (2018) formalize this idea and study its implications. In their framework, the implementation of an SCR is achieved by designing a generalization of the effectivity relationship, introduced by Sertel (2001), called a code of rights.Footnote 2

A code of rights specifies, for each pair of outcomes (x, y), a collection of coalitions \(\gamma (x,y)\) that are effective at moving from x to y. The code of rights is more flexible than the effectivity function, as it allows the strategic options of coalitions to depend on how the status quo outcome is reached (i.e., on the current state).

Note that Koray and Yildiz (2018) introduce the more general concept of rights structures, which the code of rights is a special case of. In a rights structure, the state space may be augmented with other features apart from the set of outcomes Z, such as a preference profile. By restricting attention to the set of outcomes as the state space, the design exercise admits a very intuitive interpretation, bearing a straightforward analogy to the exercise of rights in the real world. This is in contrast to the more general rights structure framework which, although has shown to be more permissive for the implementation exercise, it does not easily conform with our intuition. We believe that the limitations that implementation by codes of rights bears better convey the constraints of the mechanism design exercise in a real world scenario, thus making it more applicable.

As a coalitional solution, Koray and Yildiz (2018) adopt the core defined in terms of strong domination. Outcome x strongly dominates y if a coalition K exists that is effective at moving from x to y, and this move is beneficial for all members of K. The weak core is the set of outcomes that are not strongly dominated.

The core can also be defined in terms of weak domination. That is, x weakly dominates y if a coalition K exists that is effective at moving from x to y, and this move is beneficial for at least one member of K and non-harmful for others. The strong core is the set of all outcomes that are not weakly dominated.

Most studies tend to utilize the notion of the weak core that admits in general more simple results. However, whether one should consider the weak or the strong core as a solution concept is not straightforward. That is, there is no clear reason to prefer one over the other for any environment, as such choice relies heavily on the particular issues that arise in each case. For example, as pointed out in Roth and Postlewaite (1977), in a market with indivisibilities, an important consequence of using weak instead of strong domination is that the strong core has no instability problems. Moreover, in the exchange market model of Shapley and Scarf (1974), the strong core is included in the set of competitive allocations (Wako 1984).

In this paper, we fully characterize the set of implementable SCRs in strong core by codes of rights (Theorem 1). Our characterization consists of the well-known unanimity condition and a new condition that we call SC-monotonicity, a variant of strong monotonicity as found in Korpela et al. (2020), who study implementation in codes of rights in weak core.

We provide applications of our result in a rationing environment, where we show that the intersection of the no-envy correspondence with the (strongly) Pareto optimal rule satisfies our sufficient conditions and is implementable in strong core (Corollary 1). On the other hand, we show by means of an example with single-pleateaued preferences, that the previous intersection is not implementable in weak core (Example 3). More generally, there are solutions that cannot be achieved if we restrict our attention only to the weak core solution concept.

The remainder of the paper is divided into four sections. Section 2 sets out the theoretical framework and outlines the implementation model. Section 3 contains our characterization theorem. In Sect. 4 we provide some remarks and applications of our results, while in Sect. 5 we conclude and discuss points for further research.

2 Preliminaries

Our environment consists of a collection of n agents (we write N for the set of agents), a (nonempty) set of outcomes Z. By \(R_{i}\) we denote agent i’s weak preference relation on Z and \(R=(R_{1},...,R_{n})\) denotes a preference profile. As usual, the asymmetric part of \(R_{i}\) we denote by \(P_{i}\). The set of agent i’s admissible preferences is \({\mathcal {R}}_{i}\) and the set of all admissible preference profiles is denoted by \({\mathcal {R}}\).

We focus on complete information environments in which the true preference profile is common knowledge among the agents but unknown to the designer. The power set of N is denoted by \({\mathcal {N}}\), and \({\mathcal {N}}_{0} \equiv {\mathcal {N}}-\{\varnothing \}\) is the set of all nonempty subsets of N. Each group of agents, K (in \({\mathcal {N}}_{0}\)), is a coalition. By slightly abusing notation, for all \(R\in {\mathcal {R}}\) and \(K\in {\mathcal {N}}_{0}\), let x \(P_{K}\) y denote \(xR_{i}y\) for all \(i\in K\), and \(xP_{j}y\) for some \(j\in K\).

The goal of the designer is to implement a social choice rule (SCR) \(F:{\mathcal {R}}\rightarrow 2^{Z}\) defined by \(\varnothing \ne F\left( R\right) \subseteq Z\) for every \(R\in {\mathcal {R}}\). We refer to \(x\in F\left( R\right) \) as an F-optimal outcome at R. To implement his goal, the designer devises a code of rights \(\gamma \), which is a (possibly empty) correspondence \(\gamma :Z\times Z\twoheadrightarrow {\mathcal {N}}\). \(\gamma \) specifies, for each pair of outcomes \(\left( x,y\right) \), a family of coalitions \(\gamma \left( x,y\right) \) entitled to approve a change from outcome x to y.

For any cooperative game \(\left( \gamma ,R\right) \), we say that x (strongly) dominates y if there exists a coalition K such that (i) \(K\in \gamma \left( y,x\right) \) and (ii) \(xP_{i}y\) for all \(i\in K\). The definition of weak domination is obtained by relaxing condition (ii) to read (iia) \(xP_{K}y\). The core of the game \(\left( \gamma ,R\right) \), denoted by \(C\left( \gamma ,R\right) \), is the set of undominated outcomes. The strong core of \(\left( \gamma ,R\right) \), denoted by \(SC\left( \gamma ,R\right) \), is instead the set of weakly undominated outcomes.

Definition 1

A code of rights \(\gamma \) implements F in strong core, simply SC-implements F, if \(F\left( R\right) =SC\left( \gamma ,R\right) \) for all \(R\in {\mathcal {R}}\). If such a code of rights exists, then F is SC-implementable by a code of rights.

Definition 2

A code of rights \(\gamma \) implements F in core, simply C-implements F, if \(F\left( R\right) =C\left( \gamma ,R\right) \) for all \(R\in {\mathcal {R}}\). If such a code of rights exists, then F is C-implementable by a code of rights.

Given preference profile R and outcome x, let agent i’s lower contour set be defined by \(L_{i}\left( x,R\right) \equiv \left\{ y\in Z|xR_{i}y\right\} \), and agent i’s strict lower contour set be defined by \(SL_{i}\left( x,R\right) =\{y\in Z|xP_{i}y\}\). Fix any \(i\in N\), any \(R,R^{\prime }\in {\mathcal {R}}\) and any \(x\in Z\). We say that \(R^{\prime } \) is a monotonic transformation of R at x for agent i if \(L_{i} (x,R)\subseteq L_{i}(x,R^{\prime })\). If \(R^{\prime }\) is a monotonic transformation of R at x for each agent \(i\in N\), we say that \(R^{\prime }\) is a monotonic transformation of R at x. F satisfies monotonicityFootnote 3 provided that for all \(R,R^{\prime }\in {\mathcal {R}}\) and all \(x\in Z\), if \(x\in F\left( R\right) \) and \(R^{\prime }\) is a monotonic transformation of R at x, then \(x\in F\left( R^{\prime }\right) . \)

3 A full characterization

As we will show later, monotonicity is not a necessary condition for SC-implementation by a code of rights. Thus, we introduce below a new condition, called strong core monotonicity, simply SC-monotonicity, using the following additional notation. For any coalition \(K\in {\mathcal {N}}_{0}\), profile \(R\in {\mathcal {R}}\), and outcome \(x\in Z\), let

Now, we define our notion of the “collective lower contour set” of a coalition \(K\in {\mathcal {N}}_0\) at \((x,R)\in Z\times {\mathcal {R}}\) as follows:

Finally, given a SCR F, we define:

For completeness, we assume that when \(F^{-1}(x)=\emptyset \), \(S\Lambda _K^F(x)=Z\).

Definition 3

F is SC-monotonic provided that for all \(x\in Z\) and all \(R,R^{\prime }\in {\mathcal {R}}\), if \(x\in F\left( R\right) \) and

then \(x\in F\left( R^{\prime }\right) \).

At this stage, it would be useful to compare SC-monotonicity with strong monotonicity, which is found to be necessary and almost sufficient for C-implementation in Korpela et al. (2020). First we define:

Now, strong monotonicity is stated as follows:

Definition 4

F is strongly monotonic provided that for all \(x\in Z\), \(R,R'\in {\mathcal {R}}\), if \(x\in F(R)\) and

then \(x\in F(R')\).

The difference between the two conditions lies in the “collective lower contour set” of a coalition.Footnote 4 Notice that, in the case of strong monotonicity, the collective lower contour set of coalition K is represented by \(\cup _{i\in K}L_i(x,R)\), while it becomes \(S\Lambda _K(x,R)=\cap _{i\in K}L_i(x,R)\bigcup \cup _{i\in K}SL_i(x,R)\) in the case of SC-monotonicity. In the former case, a coalition which is entitled to move from x to y will form when all of its potential members strictly prefer y to x unanimously, i.e. when \(y\notin \cup _{i\in K}L_i(x,R)\). On the other hand, in the latter case dealt with in this paper, a coalition which is entitled to move from x to y will form when all of its potential members weakly prefer y to x with the preference being strict for at least one agent, i.e. when \(y\notin S\Lambda _K(x,R)\).

As we formally show below, SC-monotonicity is a necessary condition for SC-implementation via codes of rights, and it is sufficient when combined with another necessary condition known as unanimity. This condition states that, if an outcome is at the top of the preferences of all agents, then that outcome should be selected by the SCR. The condition can be stated as follows:

Definition 5

F satisfies unanimity provided that, for all \(x\in Z\) and all \(R\in {\mathcal {R}}\), if \(Z\subseteq L_{i}(x,R)\) for all \(i\in N\), then \(x\in F\left( R\right) \).

We show that SC-monotonicity and unanimity are necessary and sufficient for SC-implementation by codes of rights.

Theorem 1

F is SC-implementable by a code of rights if and only if F satisfies the conditions of SC-monotonicity and unanimity.

Proof

“Only If”: Assume that \(\gamma \) SC-implements F. First, we show that F satisfies unanimity. For this, let \(Z\subseteq L_{i}(x,R)\) for all \(i\in N\) but, for the sake of contradiction, \(x\notin F\left( R\right) \). Then, we have \(x\notin SC\left( \gamma ,R\right) \), so there exists \(y\in Z\) and \(K\in \gamma \left( x,y\right) \) such that \(yP_{K}x\). This however contradicts our premise.

In order to show that F satisfies SC-monotonicity, assume that \(R,R'\in {\mathcal {R}}\), \(x\in F(R)\) and \(S\Lambda ^F_K(x)\subseteq S\Lambda _K(x,R')\) for all \(K\in {\mathcal {N}}_0\). Suppose that \(x\notin F(R')\). Now, \(x\in SC(\gamma ,R)\), but \(x\notin SC(\gamma ,R')\), as \(\gamma \) SC-implements F. Then, there exist \(y\in Z\) and \(K\in \gamma (x,y)\) such that \(yP'_Kx\), implying that \(y\notin S\Lambda _K(x,R')\). This means that \(y\notin S\Lambda _K^F(x)\), Then, however, there is some \(R''\in F^{-1}(x)\) with \(y\notin S\Lambda _K(x,R'')\). That is, \(yP''_Kx\). So, \(x\notin SC(\gamma ,R'')\) since \(K\in \gamma (x,y)\), in contradiction with \(x\in F(R'')=SC(\gamma ,R'')\).

“If”: Assume that F satisfies the conditions of SC-monotonicity and unanimity. Let us define a code of rights \(\gamma :Z\times Z\twoheadrightarrow {\mathcal {N}}\) as follows. The range of F is the set \(F\left( {\mathcal {R}}\right) =\left\{ x\in Z|x\in F\left( R\right) \text { for some }R\in {\mathcal {R}}\right\} \). Given any \(x,y\in Z\) and \(K\in {\mathcal {N}}_0\), we let

-

(a)

\(K\in \gamma (x,y)\) if and only if \(y\in S\Lambda _K^F(x)\), when \(x\in F({\mathcal {R}})\),

-

(b)

\(K\in \gamma (x,y)\), when \(x\in Z\setminus F({\mathcal {R}})\).

Take any \(R\in {\mathcal {R}}\). In order to show that \(F(R)\subseteq SC(\gamma ,R)\), pick any \(x\in F(R)\). Also, take any \(K\in {\mathcal {N}}_0\) and any \(y\in Z\) with \(yP_Kx\). Now, however, \(y\notin S\Lambda _K^F(x)\), implying that \(K\notin \gamma (x,y)\) by part (a) above, as \(x\in F({\mathcal {R}})\). Thus, \(x\in SC(\gamma ,R)\).

Conversely, take any \(x\in SC(\gamma ,R)\). First, consider the case where \(x\in Z\setminus F({\mathcal {R}})\). Take any \(i\in N\) and \(y\in Z\). Since \(\{i\}\in \gamma (x,y)\) and \(x\in SC(\gamma ,R)\), we conclude that \(xR_iy\) for all \(i\in N\). So, \(x\in F(R)\) by unanimity of F.

Now, assume that \(x\in F({\mathcal {R}})\). Then, \(x\in F(R')\) for some \(R'\in {\mathcal {R}}\). Suppose that \(S\Lambda _K^F(x)\nsubseteq S\Lambda _K(x,R)\) for some \(K\in {\mathcal {N}}_0\). That is, there is some \(y\in S\Lambda _K^F(x)\) with \(y\notin S\Lambda _K(x,R)\). Now, \(K\in \gamma (x,y)\) by (a) since \(y\in S\Lambda _K^F(x)\), and \(yP_Kx\) since \(y\notin S\Lambda _K(x,R)\), contradicting that \(x\in SC(\gamma ,R)\). Thus, \(S\Lambda _K^F(x)\subseteq S\Lambda _K(x,R)\) for all \(K\in {\mathcal {N}}_0\), implying that \(x\in F(R)\) by SC-monotonicity. This completes the proof. \(\square \)

4 Remarks and applications

4.1 Remarks

In this section, we provide some applications and remarks on our characterization theorem. First, we show that SC-monotonicity and monotonicity are logically independent. To see this, let us consider the following SCRs:

Weak Pareto solution, WPO. For all \(R\in {\mathcal {R}}\),

\(WPO\left( R\right) \equiv \left\{ x\in Z|\text {for all }y\in Z-\left\{ x\right\} \text {\ there exists }i\in N\text {\ such that }xR_{i}y\right\} \).

Pareto solution, PO. For all \(R\in {\mathcal {R}}\),

\(PO\left( R\right) \equiv \left\{ x\in Z|\text {there exists no }y\in Z-\left\{ x\right\} \text { such that }y\text { }P_{N}\text {\ } x\right\} \).

It is well-known that the weak Pareto solution satisfies monotonicity.Footnote 5 We show first in Example 1 below that it does not satisfy SC-monotonicity.

Example 1

There are two players in \(N\equiv \left\{ 1,2\right\} \), three preference profiles in \({\mathcal {R}}=\left\{ R,R^{\prime },R^{\prime \prime }\right\} \), and two outcomes in \(Z\equiv \left\{ x,y\right\} \). Preferences are represented in the table belowFootnote 6:

Notice that \(WPO\left( R\right) =WPO\left( R^{\prime }\right) =\left\{ x,y\right\} \) and \(WPO\left( R^{\prime \prime }\right) =\left\{ y\right\} \). Let us check that the weak Pareto solution does not satisfy our condition SC-monotonicity. To this end, let us note that:

-

(i)

\(L_{1}\left( x,R\right) =\left\{ x,y\right\} \), \(SL_{1}\left( x,R\right) =\varnothing \), \(L_{2}\left( x,R\right) =\left\{ x\right\} \) and \(SL_{2}\left( x,R\right) =\varnothing \);

-

(ii)

\(L_{1}\left( x,R^{\prime }\right) =\left\{ x\right\} \), \(SL_{1}\left( x,R^{\prime }\right) =\varnothing \), \(L_{2}\left( x,R^{\prime }\right) =\left\{ x,y\right\} \) and \(SL_{2}\left( x,R^{\prime }\right) =\varnothing \);

-

(iii)

\(L_{1}\left( x,R^{\prime \prime }\right) =L_{2}\left( x,R^{\prime \prime }\right) =\left\{ x\right\} \) and \(SL_{1}\left( x,R^{\prime \prime }\right) =SL_{2}\left( x,R^{\prime \prime }\right) =\varnothing \).

Thus, by construction, it can be verified that \(S\Lambda _{K}^{WPO}\left( x\right) =\left\{ x\right\} \) for all \(K\in {\mathcal {N}}_{0}\). WPO does not satisfy SC-monotonicity because \(x\in WPO\left( R\right) \), \(S\Lambda _{K}^{WPO}\left( x\right) \subseteq S\Lambda _K(x,R'')=\{x\}\) for all \(K\in {\mathcal {N}}_{0}\) and yet \(x\notin WPO\left( R''\right) \).

We showed that WPO does not satisfy SC-monotonicity and is thus not SC-implementable. In Proposition 1, we show that PO on the other hand is SC-implementable.

Proposition 1

The Pareto solution PO is SC-implementable.

Proof

The fact that PO satisfies unanimity is obvious. We will prove that PO satisfies SC-monotonicity. For the sake of contradiction, consider \(x\in PO(R)\setminus PO(R^{\prime })\) for some \(R,R^{\prime }\in {\mathcal {R}}\), and suppose that for all \(K\in {\mathcal {N}}_{0}\), we have \(S\Lambda _{K}^{PO}\left( x\right) \subseteq S\Lambda _K(x,R')\). Since \(x\notin PO(R^{\prime })\), there must exist \(y\in Z\), such that for all \(i\in N\), \(yR_{i}^{\prime }x\) and \(yP_{j}^{\prime }x\), for some \(j\in N\). Now take \(K=N\). We now have that \(y\notin L_{N}\left( x,R^{\prime }\right) \) and \(y\notin SL_{N}\left( x,R^{\prime }\right) \), so, by our assumption, \(y\notin S\Lambda _{N}^{PO}\left( x\right) \). Then, by the definition of \(S\Lambda _{N}^{PO}\left( x\right) \), there must exist \(R^{\prime \prime }\in {\mathcal {R}}\) where \(x\in PO(R^{\prime \prime })\), such that \(y\notin S\Lambda _K(x,R'')\equiv L_K(x,R'')\bigcup SL_K(x,R'')\). This in turn implies that for all \(i\in N\), we have \(yR_{i}^{\prime \prime }x\), and for some \(j\in N\), we have \(yP_{j}^{\prime \prime }x\). This however contradicts our assumption that \(x\in PO(R^{\prime \prime })\). We conclude that PO satisfies SC-monotonicity as well, and, by Theorem 1, we have that PO is SC-implementable. This completes the proof.

Finally, consider the following example:

Example 2

There are two players in \(N\equiv \left\{ 1,2\right\} \), two preference profiles in \({\mathcal {R}}=\left\{ R,R^{\prime }\right\} \), and two outcomes in \(Z\equiv \left\{ x,y\right\} \). Preferences are represented in the table below:

Now, \(PO\left( R\right) =\left\{ x,y\right\} \) and \(PO\left( R^{\prime }\right) =\left\{ y\right\} \). The Pareto solution does not satisfy monotonicity because \(x\in PO\left( R\right) \), \(R^{\prime }\) is a monotonic transformation of R at x, and \(x\notin PO\left( R^{\prime }\right) \).

Thus, PO does not satisfy monotonicity verifying the logical independence of SC-monotonicity and monotonicity. Note that Korpela et al. (2020) show that strong monotonicity, is necessary and almost sufficient for C-implementation by codes of rights. Since strong monotonicity implies monotonicity (see Korpela et al. 2020; p. 8), the examples above also show that SC-monotonicity and strong monotonicity are logically independent. On the same issue, Korpela et al. (2018; Example 2, p. 23) show that the weak Pareto solution is strongly monotonic. Thus, we conclude that while PO is implementable in strong core, it is not in weak core, while the opposite is true for WPO.

Additionally, note that, a code of individual rights is a code of rights that allocates blocking powers only to single individuals. Korpela et al. (2020) introduce a stronger variant of strong monotonicity, called singleton strong monotonicity, which is necessary and sufficient for C-implementation by a code of individual rights when combined with the unanimity condition.Footnote 7 When only individual deviations are allowed, the core defined by weak domination coincides with the core defined by strong domination, and so C-implementation by individual codes of rights is equivalent to SC-implementation by individual codes of rights. This implies that SC-monotonicity is equivalent to singleton strong monotonicity when only individual deviations are allowed.

As a final remark, note that singleton strong monotonicity implies monotonicity. Since the strong Pareto solution violates monotonicity, it follows that it does not satisfy singleton strong monotonicity. However, the strong Pareto solution is SC-monotonic. It follows that coalitions matter in the design of codes of rights implementing in strong core equilibria.

4.2 Applications

Strong core has a bite relative to its weak counterpart, when indifferences matter. Indeed, in many instances where indifferences are inconsequential, the two equilibrium notions coincide.Footnote 8 Consider for example a one-to-one matching environment with strict preferences over partners. Korpela et al. (2020) show in this case that the stable rule is C-implementable. While indifferences are allowed among matchings, they have no bite, as agents only care about their partners. The reader then can easily verify that the stable rule is SC-implementable as well in this case.

In order to further outline the significance of our characterization theorem, we turn our focus to rationing problems,Footnote 9 where indifferences matter. We proceed with some formal definitions.

A social planner desires to allocate an infinitely divisible amount \(M\in {\mathbb {R}} _{+}\) among the agents. An allocation is a vector \(x=(x_{1},x_{2},...,x_{n})\in {\mathbb {R}} _{+}^{n}\), such that \(\sum _{i\in N}x_{i}=M\). Each agent \(i\in N\) has a weak preference relation \(\succsim _{i}\)on \( {\mathbb {R}} _{+}\), with \(\succ _{i}\) and \(\sim _{i}\) as its asymmetric and symmetric counterparts respectively. The set of all admissible preferences for agent i is denoted by \({\mathcal {L}}_{i}\). In this setting then, the set of outcomes consists of the set of allocations, that is, \(Z\equiv \{x\in {\mathbb {R}} _{+}^{n}|\sum _{i\in N}x_{i}=M\}\) and agents’ preferences naturally extend to the set of outcomes Z as follows:

For all \(i\in N\), \(\succsim _i \in {\mathcal {L}}_i\) and \(x,y\in Z\):

A desirable rule that has attracted attention from the normative viewpoint is the no-envy correspondence which is defined as follows:

Definition 6

The no-envy correspondence \(NE:{\mathcal {R}}\rightarrow 2^{Z}\) is defined such that, for all \(x\in Z\), we have \(x\in NE(R)\) if and only if for all \(\{i,j\}\subseteq N,x_{i}\succsim _{i}x_{j}\).

We now show that the no-envy correspondence satisfies SC-monotonicity.

Proposition 2

NE satisfies SC-monotonicity.

Proof

Consider \(R,R^{\prime }\in {\mathcal {R}}\), where \(x\in NE(R){\setminus }NE(R^{\prime })\), while for all \(K\in {\mathcal {N}}_{0}\), \(S\Lambda _{K}^{F}\left( x\right) \subseteq S\Lambda _K(x,R')\). Since \(x\notin NE(R')\), there exists \(\{i,j\}\subseteq N\), where \(x_{j}\succ _{i}^{\prime }x_{i}\). Define \(y=(y_1,y_2,...,y_n)\), such that for all \(y_k\) where \(k\notin \{i,j\}\), \(y_k=x_k\), while \(y_i=x_j\) and \(y_j=x_i\). That is, y is the allocation where i’s and j’s assignments are permuted, while all other agents’ assignments are the same as in x. Now take \(K=\{i\}\) and notice that \(y\notin L_{i}(x,R')=L_{i}\left( x,R^{\prime }\right) {\displaystyle \bigcup } SL_{i}\left( x,R^{\prime }\right) =S\Lambda _i(x,R') \). Then, by our assumption and the definitionFootnote 10 of \(S\Lambda _{K}^{F}\left( x\right) \), there must exist \(R^{\prime \prime }\in {\mathcal {R}}\) with \(x\in NE(R^{\prime \prime })\), such that \(y\notin L_{i}\left( x,R^{\prime \prime }\right) {\displaystyle \bigcup } SL_{i}\left( x,R^{^{\prime \prime }}\right) =L_{i}(x,R^{\prime \prime })\). It follows that \(x_{j}\succ _{i}^{^{\prime \prime }}x_{i}\) as well and \(x\notin NE(R^{\prime \prime })\), which is a contradiction. Therefore, NE satisfies SC-monotonicity. This completes the proof. \(\square \)

SC-monotonicity is preserved under intersections, which is stated in our Corollary below:

Corollary 1

Suppose that \(PO\cap NE\ne \emptyset \). Then it is SC-implementable.

Proof

Follows from Propositions 1 and 2 and Theorem 1. \(\square \)

We have verified that the intersection of PO and NE is SC-implementable. The reader might note that this result does not depend upon the specifics of the rationing problem and it holds in any abstract social choice setting, where \(PO\cap NE\ne \emptyset \).

We will now show an example where the previous intersection is not C-implementable. Specifically, we consider single-plateaued preferences in the rationing problem.Footnote 11 Formally, preferences are single-plateaued, if for every agent i there exist \({\underline{x}}_{i},{\overline{x}}_{i}\in {\mathbb {R}} _{+}\), such that for all \(x_{i},y_{i}\in {\mathbb {R}} _{+}:\)

-

1.

\(y_{i}<x_{i}\le {\underline{x}}_{i}\) implies \(x_{i}\succ _{i}y_{i}\).

-

2.

\(y_{i}>x_{i}\ge {\overline{x}}_{i}\) implies \(x_{i}\succ _{i}y_{i}\).

-

3.

\(x_{i},y_{i}\in [{\underline{x}}_{i},{\overline{x}}_{i}]\) implies \(x_{i}\sim y_{i}\).

Single-plateaued preferences generalize single-peaked preferences and have been central in studies of voting and public goods environments. Intuitively, an agent has single-plateaued preferences if there exists an interval such that, preference is strictly increasing (decreasing) to the left (right) of the interval, while the agent is indifferent among assignments in the interval, which correspond to the most preferred ones. Consider now the following example:

Example 3

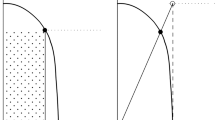

Let \(N\equiv \{1,2\}\), \({\mathcal {R}}=\{R,R^{\prime }\}\), \(M=20\), while the preferences are depicted in Fig. 1.

Single-plateaued preferences, Example 3

The left dashed graph corresponds to agent 1’s preferences in R, \(R_{1}\). The left solid graph corresponds to agent 1’s preferences in \(R'\), \(R'_{1}\). Finally, the right solid graph represents the preferences of agent 2 both in R and \(R^{\prime }\).

Consider the allocation \(x=(10,10)\in (PO\cap NE)(R)\). Then, notice that agent 1’s preferences change from R to \(R^{\prime }\) in a monotonic transformation at x: \(L_1((10,10),R)=L_1((10,10),R')={\mathbb {R}}_+\). Moreover, agent 2’s preferences remain unchanged. However, notice that \(x\notin PO(R^{\prime })\), as there is a weak Pareto improvement to \(y=(5,15)\). As the change from R to \(R^{\prime }\) is a monotonic transformation at x, we verify that PO does not satisfy monotonicity. Since strong monotonicity implies monotonicity (Korpela et al. 2020), it follows directly that \(PO\cap NE\) is not C-implementable. This point outlines the importance of the right choice of equilibrium concept according to the environment in hand, as well as the relevance of the strong core as a solution concept.

5 Conclusion

We have studied the problem of implementing a social choice rule with codes of rights when the solution concept is the strong core, by characterizing the set of implementable rules. With our results we also aim to further motivate the study of mechanism design with cooperative game-theoretic devices, a special case of which is a code of rights. Additionally, we aim to outline the relevance of the strong core as a solution concept in economic design.

Our research can be taken further in several directions. Apart from applications of our results in more structured environments, a particularly fruitful avenue would be to relax the myopic assumption in the solution concept. Indeed, it is not clear yet what implications does farsightedness bear for the literature.

Notes

Mcquillin and Sugden (2011) propose a similar notion, named the game in transition function form, as a generalization of effectivity functions.

Monotonicity, also known as “Maskin monotonicity”, is necessary for full implementation in Nash equilibria (Maskin 1999). In this paper, we refer to it as “monotonicity”.

We thank an anonymous referee for suggesting this interpretation.

See for example Maskin (1999). Even though the condition we call monotonicity in our setting is slightly different than his, as ours concerns coalitions in general rather than individual agents, the proof still holds.

As usual, \(_{b}^{a}\) for agent i means that he/she strictly prefers a to b, while a, b means that i is indifferent between a and b. Notice that preference profile \(R'\) is not necessary for the example. It is merely added to outline the formulation of SC-monotonicity in a more general case with more than two preference profiles.

F is singleton strongly monotonic provided that, for all \(x\in Z\) and all \(R,R'\in {\mathcal {R}}\), if \(x\in F(R) \) and

$$\begin{aligned} {\displaystyle \bigcap \limits _{{\hat{R}}\in F^{-1}\left( x\right) }} L_{i}(x,{\hat{R}})\subseteq L_{i}(x,R')\text { for all }i\in N\text {,} \end{aligned}$$then \(x\in F\left( R'\right) \).

Notice that if we confine preferences to linear orders, SC-monotonicity collapses to strong monotonicity. We thank a referee for pointing to this useful remark.

For Nash implementation results in rationing problems see Thomson (2010).

Note that in this case \(S\Lambda _{i}^{NE}\left( x\right) =\bigcap _{R''\in NE^{-1}(x)}(L_i(x,R'')\cup SL_i(x,R''))\), because \(F=NE\), \(K=\{i\}\), and \(R''\) is the preference profile we want.

Ehlers (2002) studies strategy-proofness in single-plateaued environments. For Nash implementation results, see Doghmi Ziad (2013).

References

Abreu D, Matsushima H (1992) Virtual implementation in iteratively undominated strategies: complete information. Econometrica 60:993–1008

Abreu D, Sen A (1990) Subgame perfect implementation: a necessary and almost sufficient condition. J Econ Theory 50:285–299

Benoit J-P, Ok E (2008) Nash implementation without no-veto power. Games Econ Behav 64:51–67

Chwe MS-Y (1994) Farsighted coalitional stability. J Econ Theory 63:299–325

Doghmi A, Ziad A (2015) Nash implementation in private good economies with single-plateaued preferences and in matching problems. Math Soc Sci 73:32–39

Ehlers L (2002) Strategy-proof allocation when preferences are single-plateaued. Rev Econ Des 7:105–115

Jackson MO (1992) Implementation in undominated strategies: a look at bounded mechanisms. Rev Econ Stud 59:757–775

Jackson MO (2001) A crash course in implementation theory. Soc Choice Welfare 18:655–708

Koray S, Yildiz K (2018) Implementation via rights structures. J Econ Theory 176:479–502

Korpela V, Lombardi M, Vartiainen H (2020) Do coalitions matter in designing institutions? J Econ Theory 185:1–19

Korpela V, Lombardi M, Vartiainen H (2018) Do coalitions matter in designing institutions?. Available at SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3305209

Maskin E (1999) Nash equilibrium and welfare optimality. Rev Econ Stud 66:23–38

Maskin E, Moore J (1999) Implementation and renegotiation. Rev Econ Stud 66:39–56

Maskin E, Sjöström T (2002) Implementation theory. In: Arrow K, Sen AK, Suzumura K (eds) Handbook of social choice and welfare. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, pp 237–288

Mcquillin B, Sugden R (2011) The representation of alienable and inalienable rights: games in transition function form. Soc Choice Welf 37:683–706

Moore J, Repullo R (1988) Subgame perfect implementation. Econometrica 56:1191–1220

Mukherjee S, Muto N, Ramaekers E, Sen A (2019) Implementation in undominated strategies by bounded mechanisms: the Pareto correspondence and a generalization. J Econ Theory 180:229–243

Ray D, Vohra R (2015) The farsighted stable set. Econometrica 83:977–1011

Roth A, Postlewaite A (1977) Weak versus strong domination in a market with indivisible goods. J Math Econ 4:131–137

Sertel MR (2001) Designing rights: Invisible hand theorems, covering and membership, mimeo, Bogazici University

Shapley LS, Scarf HE (1974) On cores and indivisibility. J Math Econ 1:23–37

Thomson W (2010) Implementation of solutions to the problem of fair division when preferences are single-peaked. Rev Econ Des 14:1–2

Wako J (1984) A note on the strong core of a market with indivisible goods. J Math Econ 13:189–194

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lombardi, M., Savva, F. & Zivanas, N. Implementation in strong core by codes of rights. Soc Choice Welf 60, 503–515 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-022-01425-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-022-01425-3