Abstract

When including outside pressure on voters as individual costs, sequential voting (as in roll call votes) is theoretically preferable to simultaneous voting (as in recorded ballots). Under complete information, sequential voting has a unique subgame perfect equilibrium with a simple equilibrium strategy guaranteeing true majority results. Simultaneous voting suffers from a plethora of equilibria, often contradicting true majorities. Experimental results, however, show severe deviations from the equilibrium strategy in sequential voting with not significantly more true majority results than in simultaneous voting. Social considerations under sequential voting—based on emotional reactions toward the behaviors of the previous players—seem to distort subgame perfect equilibria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Decision making by voting come in various forms, where some procedural differences can have apparent consequences for the results of a vote: absolute versus relative majority, simple versus qualified majority, or weighted voting versus equal suffrage. Other design characteristics may have an effect as well, and little has been done to theoretically as well as experimentally compare voting behavior under simultaneous versus sequential voting. Here, sequential voting is understood as voters casting their votes publicly one after another on one issue or candidate, and not (as often understood) as voting on a sequence of issues or candidates. Theoretically, sequential voting is different from simultaneous voting with the potential to fundamentally change the voting behavior.

The most common scheme is simultaneousFootnote 1 (simple relative) majority voting with equal weights. The most prominent examples of sequential voting are roll call votes in the US Senate. These votes are recorded and sequential, where senators are requested, in alphabetical order, to vote “yea” or “nay”. Also many other parliaments follow this procedure, but after the introduction of electronic voting, the dynamic character of the voting procedure is lost. Although still called “roll call votes”, they are transformed to recorded simultaneous votes.Footnote 2 Meanwhile, roll call voting is often used as a synonym for recorded voting (compare Ainsley et al. 2020, investigating the application of “roll call votes” in 145 legislative chambers). However, in the literature on information cascades, roll call voting always means dynamic voting, and there is also a minority of US states which apply role call voting in its original form: “Fourteen chambers use a traditional manual roll-call system in which the clerk calls the roll orally, records each member’s vote on paper, and then tallies the ayes and nays” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voting_methods_in_deliberative_assemblies#State_legislatures). If smaller parliaments use roll call votes then electronic devices are neither necessary nor available, and members are called to vote one after another. An example is the Boston City Council (https://library.municode.com/nh/keene/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=PTIICOOR_APXARUORCO). Also in the early Roman Republic there were roll call votes as in the US Senate. Further examples of sequential votes are the US primaries and all elections where late voters get (usually informally) information about the behavior of earlier voters, for example in countries where voting is possible over several days or which include different time zones.

The coexistence of simultaneous and sequential voting leaves the question open if one of the two procedures has a theoretical or practical advantage. This question of which of the two democratic mechanism is favorable need to be answered experimentally, as differences in voting mechanisms would not be a problem if all voters vote according to their “true preference.” Do voters always dare to vote their preferred outcome? In a comparison of parliamentary systems in 162 countries Kędzia and Hauser (2011, p. 2) state: “Indeed, the relationship between the concept of a free parliamentary mandate, widely recognized as an essential condition for democracy, and party discipline as a functional premise of the party system poses one of the major challenges to the present-day concept of parliamentary system of government.” We do not take a stance in this discussion, but will investigate effective pressure from party whips and other sources under simultaneous versus sequential voting. Most formal models of voting behavior neglect outside pressure, which can be extraordinary strong as the following example illustrates. On the 3rd of September 2019, the British Conservative Party withdrew the whip from 21 of its MPs because they voted against the party line. This means, they were practically expelled from their party. Only ten of the suspended MPs had the whip restored with four that could run in the December 2019 election as Tory candidates (retaining their seats); all others who rebelled against their party lost their seats. This is an extreme example of the outside pressure under which members of parliament and other voting bodies make their decisions. Outside pressures can stem from party whips (as in the provided example), from their electorate, lobbyists, or more generally the media. Thus, voting according to the individual preferences often comes with certain costs. The preferred outcome is not necessarily connected with the own confirmatory vote. Therefore, “true preferences” are simply defined under the assumption that the own vote is decisive. Then, not only the opportunity costs of voting counts, but also the individual value of an accepted proposal.

Thus, we assume preferences of voters that take into account costs (positive or negative values) for confirmatory votes and benefits (positive or negative values) for an accepted proposal. Models with individually opposing values have been proposed for simultaneous and sequential voting (Dal Bó 2007; Groseclose and Milyo 2010, 2013; Spenkuch et al. 2018; Bolle 2018, 2019). Under complete information, sequential voting behavior is theoretically rather simple for all kind of voting rules (absolute or relative majority, weighted voting, double majorities, etc.). Complete information means that each voter knows on their turn the decisions of all previous voters and the true preferences of all later voters (how these would vote if their vote would be decisive). Then, according to the unique subgame perfect equilibrium, the current voter decides as if all later voters would follow their true preferences. This (apparently often counter-factual) assumption allows a simple description of equilibrium behavior, which guarantees that voting results mirror true majorities, i.e. the result is the same as if all voters had voted according to their true preferences. The unique and true majority guaranteeing equilibrium of sequential votes has no pendent under simultaneous voting. Under simultaneous voting with equal weights, we mostly have a unique pure strategy equilibrium, but this is often rather implausible as it competes with a huge number of mixed and pure/mixed strategy equilibria. Only some pure strategy equilibria honor true majorities (others not); all pure/mixed strategy equilibria lead to random results. Therefore, relying on theory, sequential voting seems to be clearly advantageous over simultaneous voting.Footnote 3

Rarely people strictly follow behavioral rules based on game theoretic methods. The main reasons for deviations from theoretic predictions are assumed to be (i) social preferences and (ii) bounded rationality. For simultaneous and sequential voting, quite different heuristics may be applied. Thus, it remains an empirical question which of the two voting mechanisms should be preferred. In actual behavior, are there more true majority results under sequential or simultaneous voting? There have been empirical investigations of parliamentary decisions, for example of the roll call votes in the US Senate (Clinton et al. 2004; Spenkuch et al. 2018), but none directly compares sequential with simultaneous voting mechanisms.Footnote 4 We report the results of an experimental voting game, with the only mechanism difference of sequential versus simultaneous voting, and an otherwise identical decision situation. The theoretical model is introduced first, in Sect. 2, together with the derived equilibria. Sect. 3 describes the experimental details of the implemented voting games. The voting results are reported in Sect. 4 and discussed in Sect. 5 with concluding remarks.

2 Voting games with outside pressure

Our voting games belong to a class of games called binary threshold public good (BTPG) games, where players have only two possible actions and where a “public good” is produced (a proposal is accepted) if and only if a certain threshold is passed, that means “enough” players decide for the proposal. Abstention is not possible or has the same effect as voting against the proposal. Without abstention relative and absolute majority requirements for passing the threshold are the same. Furthermore, we focus on votes where all voters have equal weights.

Definition 1

In Voting Games (VG), players have two possible actions, called “Yes” and “No.” If the proposal is not accepted and if player i votes No, then her revenue is \(R_i=0\), i.e., the status quo is evaluated as zero. Player i bears costs \(c_i\) if she votes Yes and she enjoys benefits \(G_i\) if the proposal is accepted. Players maximize their expected revenues \(R_i=p_{acc} G_i-p_i c_i\), with \(c_i\), \(G_i\), and \(R_i\) as cardinal utilities, and where \(p_{acc}\) is the probability for the proposal to be accepted and \(p_i\) the probability of i of voting Yes to support the proposal with \(i=1,\ldots ,n\).

In VG, costs and benefits have the character of opportunity costs and benefits. The costs \(c_i\) may be described as the utility of voting No minus the utility of voting Yes while benefits are constant, i.e., if the proposal is accepted or rejected independent of i’s vote. If \(c_i\) is positive then voting Yes is disadvantageous (i’s party wants her to vote No), if \(c_i\) is negative it is advantageous. The costs of deviating from the party line can be extremely large as the example in the introduction shows. But party whips have also smaller sticks and carrots, both describing opportunity costs (Kilgour et al. 2006): “A ’loyal’ MP who votes the party line will be a candidate for promotion (if in the government party, perhaps to Cabinet), or other benefits from the party, such as interesting trips or appointment to an interesting House committee. A ’disloyal’ MP who votes against the party leadership may be prevented from ascending the political ladder and could ultimately be thrown out of the party caucus.”

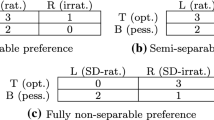

We distinguish four cases. If \(0<c_i<G_i\), player i wants the proposal to be accepted without voting Yes. If \(c_i<0<G_i\) or \(c_i<G_i<0\), i has the dominant strategy to vote Yes. If \(0<G_i<c_i\) or \(G_i<0<c_i\) , i has the dominant strategy to vote No. If \(G_i<c_i<0\), i wants to free-ride on the No votes of others. When all players with dominant strategies are removed from the game, while taking into account their dominant strategy decisions, then remains a game with n critical players, where a specific number k of Yes votes are necessary for the proposal to be accepted. If \(k=0\) or \(k>n\), then the dominant strategy players alone determine the outcome of the proposal. Here we concentrate on the other cases \(1\le k\le n\), where the n critical voters decide about the outcome of the vote.

Definition 2

-

(i)

\(N=N^++N^-\) is the set of critical voters. For all \(i\in N^+\) we have \(0<c_i<G_i\) and for all \(i\in N^-\) we have \(G_i<c_i<0\). The number of voters in \(N^+\) and \(N^-\) are \(n^+\) and \(n^-\).

-

(ii)

Voters from \(N^+(N^-)\) are called positive (negative) players.

-

(iii)

We define the true preference of \(N^+\) as voting Yes and of \(N^-\) as voting No.

-

(iv)

If the number of necessary votes for the acceptance of the proposal is \(k\le n^+\), acceptance is called the true majority result; otherwise, rejection is called the true majority result.

For voters from \(N^+\), outside pressure is represented by their costs \(c_i\), and for voters from \(N^-\) by \(-c_i\). These are opportunity costs of voting against the party line.

2.1 Simultaneous voting

Assumption 1

\(n^+\) and \(n^-\) are common knowledge.

Proposition 1

(Groseclose and Milyo 2010) If \(0<n^-<n\) and \(n^-\ne k,k-1\) then, regarding only pure strategy equilibria, there is a unique equilibrium where all players decide according to their costs. For \(n^-=k,k-1\), no pure strategy equilibrium exists.

A unique pure strategy equilibrium is a salient candidate for equilibrium selection. Nonetheless, this does not exclude competing equilibria, in particular, because Proposition 1 predicts rather disturbing voting behavior: Except in cases with \(n^-=k,k-1\), all players vote contrary to their true preferences, and results frequently oppose true majorities. This is particularly implausible in cases of small cost/benefit ratios.Footnote 5 Ochs (1995) and Ido and Roth (1998) find that learning in zero sum games may result in different behavior than the unique mixed strategy equilibria, but in some cases convergence to equilibrium is observed. Thus, mixed strategy equilibria provide an alternative benchmark when evaluating experimental behavior.

Assumption 2

All players’ signs and cost/benefit ratios are common knowledge.

We assume that the players’ probabilities of voting Yes are \(p_i\) with \(i=1,\ldots ,n\). Player i plays a strictly mixed strategy if \(0<p_i<1\). In a strictly mixed strategy equilibrium, all players play strictly mixed strategies. Q denotes the probability of success, i.e., that k or more players vote Yes. \(Q_{+i}\) \((Q_{-i})\) denote the probability of success if i votes Yes (No). The latter depends only on \(p_j\), \(j\ne i\). \(q_i=Q_{+i}-Q_{-i}\) is the probability that i’s vote is decisive for the acceptance of the proposal. With these definitions player i’s expected revenue is

A strictly mixed strategy equilibrium requires that \(R_i\) is independent of \(p_i\), i.e.,

This requirement has been non-formally derived by Downs (1957, p. 244) and formally by Riker and Ordeshook (1968) for the binary decision of voting or not voting. If \(G_i q_i-c_i>0\) (\(<0\)), then player i votes Yes with \(p_i=1\) (\(p_i=0\)).

Proposition 2

In equilibrium,

-

(i)

if i plays a strictly mixed strategy, then \(q_i=r_i=c_i/G_i\);

-

(ii)

if \(G_i> (<) 0\), \(q_i>r_i\) implies \(p_i=1(0)\) and \(q_i<r_i\) implies \(p_i=0(1)\).

Proof

Equation 2.

If all \(c_i/G_i=r_i=\rho\) are equal, then for a symmetric strictly mixed strategy equilibrium with \(p_i=\pi\), Proposition 2 (i) implies

The right hand side in of Eq. 3 is a unimodal function of \(\pi\) with a maximum at \(\pi =(k-1)/(n-1)\). For \(k=1\) (\(k=n\)) the function is decreasing (increasing), taking all values between 0 and 1. For other k, the maximum is smaller than 1. Therefore, Eq. 3 always has a unique solution for \(k=1\) and \(k=n\) and, otherwise, it has either two solutions \(\pi ''(k)>\pi '(k)\) (for small enough \(\rho\)), one solution (border case), or no solution. In the experimental cases (\(n=4\), \(k=2\), \(\rho =0.4\), \(n^-=1\) or \(n^-=2\)) there is no pure strategy equilibrium (Proposition 1) but, for both cases the same, two mixed strategy equilibria (Proposition 2). In addition, for \(n^-=2\) one and for \(n^-=1\) two pure/mixed strategy equilibria do exist (see Appendix A).

2.2 Sequential voting

As in the case of pure strategy equilibria for simultaneous votes, we do not need Assumption 2; but we need to expand on Assumption 1.

Assumption 3

Each voter knows about every fellow voter whether she is from \(N^+\) or \(N^-\) and, when it is her turn, she knows who has already voted and how many Yes votes have been casted.

Assume that the order of voters is (voter 1, voter 2, \(\ldots\), voter n) and again disregard all voters with dominant strategies after taking their decisions into account so that the threshold for the passing of the proposal is again described by k Yes votes. The game of the remaining players consists of a sequence of subgames which are essentially described by \(k_i\).

Definition 3

\(k_i\) is the number of Yes votes from voters \(1,2,\ldots ,i-1\) plus the number of positive voters among the remaining voters \(i+1,\ldots ,n\).

Because of Assumption 3, i knows \(k_i\). If \(k_i\ge k-1\), then i and the remaining players from \(N^+\) can enforce the acceptance of the proposal. If \(k_i<k-1\), i and the remaining players in \(N^-\) can enforce rejection; but \(i\in N^+\) (\(i\in N^-\)) votes Yes (No) only if she is a pivot player.

Proposition 3

(Groseclose and Milyo 2013; Bolle 2018) The sequential voting game has a unique subgame perfect equilibrium

-

(i)

if \(k_i=k-1\), \(i\in N^-\) votes No; otherwise Yes,

-

(ii)

if \(k_i=k-1\), \(i\in N^+\) votes Yes; otherwise No,

-

(iii)

if \(n^+<k\) then the proposal is rejected; otherwise it is accepted.

Proposition 3 implies that, for the acceptance of the proposal, the order of voters is irrelevant. Individual votes, however, depend crucially on the order. For illustrative purposes, take a voting game with \(k=n^+=n^-\). If the first k players are from \(N^+\), all vote Yes—the first k voters (all \(N^+\)) because they must vote Yes in order to guarantee the acceptance of the proposal, the second k voters (all \(N^-\)) in order to incur the negative costs of voting. If the first k voters are from \(N^-\), they vote Yes because they cannot prevent the acceptance of the proposal, and the second k voters choose No because for the proposal to pass they need not incur the positive costs of voting Yes.

3 Voting experiment

All our experimental games are with \(n=4\) with always positive and negative players. Player’s endowments, costs, and benefits in eurocents are depicted in Table 1. If a positive (negative) player voted Yes, she had to bear costs \(c_i=24\) (\(c_i=-24\), being an actual gain). If at least k players contributed, then positive (negative) players received a benefit of \(G_i=60\) (loss of \(G_i=-60\)). The result of voting can be illustrated by the following case: 1 and 4 are negative and 2 and 3 are positive players; players 1 and 2 vote Yes and the others vote No, resulting in the acceptance of the proposal. Then, for player 1, endowment plus revenue is \(60-60-(-24)=24\). For player 2 it is 2\(4+60-24=60\), for player 3 it is \(24+60-0=84\), and for player 4 it is \(60-60-0=0\). A player participated in only one treatment and kept the positive or negative type during the whole experiment. Note that the endowment has no strategic significance, only the expected income differences for voting Yes or No have. The different endowments guarantee non-negative revenues in the worst-case scenario.

For simultaneous voting, three treatments were implemented. In treatments \(T_1\), \(T_2\), and \(T_3\) there were one, two, and three negative players, and with \(n^+=4-n^-\). Each subject played 32 periods in the same treatment, but the thresholds completely varied (\(k=1,2,3,4\)) in randomized order of blocks of eight repeated games. For example, in \(T_1\) one player remained the negative player with always three other positive players, and in periods 1–8 the game had \(k=3\), periods 9–16 with \(k=4\), periods 17–24 with \(k=1\), and periods 25–32 with \(k=2\).

For sequential voting only treatments \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) were carried out and only with \(k=2\).Footnote 6 Also here each subject played 32 periods in one treatment, but with different sequences of positive and negative players, and again each sequence in a randomized order of blocks of eight repeated games. For example, in \(T_2\), in periods 1-8 the sequence was (\(+,+,-,-\)), in periods 9–16 with (\(-,+,+,-\)), in periods 17-24 with (\(-,-,+,+\)), and in periods 25–27 with (\(+,-,-,+\)), where \(+\) denotes a positive player (\(N^+\)) and − denotes a negative player (\(N^-\)). Exactly these four out of the six possible sequences of positive and negative players where played in randomized orders in \(T_2\). In \(T_1\), there are exactly four possible orders with the negative player once at each of the four possible positions.

Each session consisted of eight subjects, who were randomly assigned to a positive or negative player type: six positive and two negative players in \(T_1\), four positive and four negative players in \(T_2\), and (only for simultaneous voting), two positive and six negative players in \(T_3\). Simultaneous voting consisted of 36 sessions (12 for every treatment) with 288 subjects in total. Sequential voting consisted of 24 sessions (12 for each treatment) with 192 subjects in total. Because of a programming error the sequential voting data from the first session of \(T_2\) was not properly recorded and could not be used in the analysis. The respective results for \(T_2\) under sequential voting rely on 11 sessions or independent data points.

The negative and positive players kept their sign in all periods. In every period, the eight subjects were randomly allocated to two groups with the respective restriction, i.e. in \(T_1\) both groups consisted of one negative and three positive players. This implements a stranger rematching design, as the composition of the groups changed after each round and co-players could not be identified. There is a high probability that a subject was matched with at least one player from the previous group but subjects could neither build an individual reputation nor rely on more than the average behavior of the other players. Every player decided under complete information concerning the number of positive and negative players with the respective costs and benefits, and after each round players were informed about the decision of all positive and negative co-players.

The experiments took place in the ViaLab of the European University Viadrina, implemented with z-tree (Fischbacher 2007). In the beginning subjects were given printed instructions and had the possibility to ask questions. Instructions contained general information (see Appendix B). In order to make sure that everyone fully understood the task, subjects had to answer six on-screen comprehension questions concerning outcomes and profits implied by exemplary behaviors in the games. The experiment only started after all subjects had answered these questions correctly. In the case of comprehension problems, personal advice was provided. Every eighth period, the changing of the threshold (in simultaneous voting) or the changing of the sequence (in sequential voting) was announced on a separate screen. In each period, subjects were informed on the decision screen that the group composition had been changed. For simultaneous voting, they were simply required to decide whether to vote Yes (called action A) or No (called action B). In the sequential voting games, they made their decisions under the strategy method, i.e., depending on their position in the sequence of votes, for every possible number of previous Yes votes deciding Yes or No. After all decisions in one period were completed, subjects were informed on a profit display screen, about the decisions of co-players, whether the threshold was reached, and about all individual payoffs. In the literature, in most experiments with repeated games every round is paid; in some cases one round is randomly selected for payment. In the latter case, you avoid the issue of income effects, which theoretically should not be too severe because the income from experiments is small compared with other sources of income but which behaviorally may have an effect. On the other hand, because of the small probability that a game is selected, the subjects may give single decisions less importance. When paying every period, learning is faster and we can investigate more periods with an almost constant decision rule. Therefore, there are pros and cons concerning the payment of a random period or of all periods. Our impression is that we have joined the majority of experimental researchers. An example for an also otherwise quite similar approach are the experimental investigations of Stag Hunt games and Hawk-Dove games by Feltovich (2011). Before moving to the next period, subjects were asked to evaluate their emotions concerning perceived happiness, anger, and fairness on a five point scale. In total, sessions lasted about one hour, and participants received a fully behavior contingent payment between €9.48 and €18.60 (€14.16 on average).

4 Results

The analysis of the simultaneous voting results have been published in Bolle and Otto (2020).Footnote 7 Overall, the sequential voting behavior is rather different from the theoretical prediction and the comparison with simultaneous voting shows only small differences in true majority frequencies. Especially, sequential voting is investigated further to identify systematic deviations from equilibrium.

4.1 True majority results in simultaneous and sequential voting

Simultaneous voting for \(k=2\) with \(n^-=1\) in \(T_1\) and \(n^-=2\) in \(T_2\) has no pure strategy equilibria (Proposition 1). Eq. 3 delivers the two mixed strategy equilibria which are the same in \(T_1\) and \(T_2\).Footnote 8 This simplifies the theoretical prediction of results. Under the requirement that symmetric players should play the same strategy, mainly the two mixed strategies described by (4) remain. They are the same for \(T_1\) and \(T_2\). Therefore, we skip the pure/mixed equilibria as benchmarks for average behavior. The theoretical prediction for the sequential votes (derived from Proposition 3) are averages of the four sequences with which every treatment was played. The prediction for the negative players always voting Yes is clearly rejected. Table 2 shows that under simultaneous voting, true majority results were generated 11-12 percentage points more often and under sequential voting, 20 percentage points less often than predicted. Thus, the predicted difference between simultaneous voting (Eq. 3) and sequential voting (unique subgame perfection) largely vanishes when comparing experimental behavior.

4.2 Individual behavior in sequential voting

Contrary to simultaneous votes, the benchmark equilibrium for sequential votes is unique and—because it implies truthful results—also “fully satisfactory” from the perspective of mechanism design. Therefore, the major question is to which extent subjects stick to equilibrium behavior and, if not, what are possible reasons for deviations.

Deviations from the prediction might simply be “trembling hand” errors when applying the equilibrium strategy or might result from choosing a non-equilibrium strategy. Figure 1 shows frequency distributions of the number of individual Yes votes over the eight repetitions of one game. The U-shapes suggest that most voters play according to equilibrium predictions, that some play pure non-equilibrium strategies, and that there are deviations from equilibrium as well as pure non-equilibrium strategies. A first bounded rationality approach for explaining these errors is to assume that voters aim to follow Proposition 3 but incorrectly estimate \(k_i\) (number of previous Yes votes plus number remaining positive players). \(k_i\) can take integers from 0 to 3; for \(k_i=1\) a player should vote in line with true preferences (against true preferences otherwise). Under random errors, deviations from the equilibrium strategy should be independent of the position of a player. Alternatively, we might assume that subjects do not follow Proposition 3, but aim to apply backward induction if necessary. Backward induction is unnecessary if they are the last player; then they should know whether or not their vote is decisive. In positions one, two, and three they have to carry out respectively three steps, two steps, and one step of backward induction. Under this assumption, it appears plausible that the error rates decrease with the position in the decision sequence.

Average deviations from equilibrium in different player positions are reported in Table 3. Subjects seem to have increasing problems with backward induction the further they are away from the final position—especially in the first two positions. Kübler and Weizsäcker (2004) and Bolle (2017) find that backward induction in comparable games breaks down after two steps. This observation is clearly supported here. In sequential voting, even one-level reasoning (one step of backward induction in position 3 with deviation rates of 30.7% in \(T_1\) and 37.7% in \(T_2\)) is only weakly supported. However, deviations might as well originate from other sources like for example social preferences. A more complete picture concerning deviations for player types and separated for Yes versus No predictions are provided in Table 7 of Appendix A.

4.3 Social rules and static preferences

In the experimental voting games, we might expect two versions of ethical rules.Footnote 9 The first requires voting according to true preferences. The second is striving for efficiency (maximizing the sum of incomes): in \(T_1\) the equilibrium is efficient, but in \(T_2\) it requires never following true preferences. Some of the always Yes or always No voting subjects in Fig. 1 may be interpreted as a kind of voters who consistently follow a specific social rule. An alternative interpretation is that these voters follow opposite heuristics.

Two of the standard forms of static social preferences are linear altruism/spite and inequality aversion (formal representation in Appendix C). For both types of social preferences (with plausible parameter restrictions), a voter who is not decisive would never incur costs; i.e. positive voters would not vote Yes and negative voters would not vote No. Concerning altruism, the only effect is that i’s own income decreases; for inequality aversion, the value of reduced inequality is smaller than the loss of income. Only for strong altruism directed to negative voters, a positive voter who is decisive might vote No in order to save costs for himself and negative benefits for the negative voters. But under normal assumptions (in particular, stronger altruism for fellow positive voters than for negative voters), these gains cannot compensate the loss of the positive benefits of the positive players. Regarding strong enough inequality aversion, deviations from the equilibrium strategy of Proposition 3 are possible. Imagine a decisive positive voter whose fellow positive voter has or is expected to vote No. Voting against true preferences may prevent having less income than the fellow positive voter, but reduces own income and causes less income than negative voters. At least in \(T_2\), such a deviation from Proposition 3 requires inequality aversion to fellow positive players to be stronger than to negative players. This makes the explanation of deviations from the unique strategy of Proposition 3 rather implausible.

4.4 Emotional responses

There are various experiments which find (i) in-group subjects to be favored against out-group subjects (Ahmed 2007; Ben-Ner et al. 2009; Yan and Li 2009) and (ii) inequality aversion or altruism (Bellemare et al. 2008; Visser and Roelofs 2011). It is plausible, however, that magnitudes and relations of “social feelings” as in (i) and (ii) change when people interact. We want to keep things non-formal and call the changing preferences “emotional responses.” Subjects may become disappointed or thankful toward another player, in particular with respect to an in-group player. Let us introduce this hypotheses with an example: If there is a sequence (\(-,+,+,-\)), the equilibrium result of following the strategy from Proposition 3 is a sequence of votes (Yes, No, Yes, Yes). The positive voter in position 3 is disadvantaged compared with his fellow voter in position 2 who saves the costs of voting Yes. Although position 2 plays equilibrium, position 3 may become angry about this attempt to free ride or, in other words, about passing the buck.Footnote 10 Position 3 may punish position 2 by voting No, thus making the negative player in position 4 decisive. We call such a decision “anger” driven. Alternatively, position 3 may honor position 2 voting Yes (according to true preferences but against equilibrium) by own costly voting (also according to true preferences and against equilibrium). We say that, in the latter case, the voter at position 3 expresses “solidarity” with the voter at position 2. As a consequence of anger and solidarity, both positive players are not worse or better off than their exploitative or altruistic predecessor. This can be considered as a form of extreme inequity aversion (usually excluded) concerning the players with the same sign (compare Bolton 1997; Otto 2020).

The frequencies of individual choices in two (out of the eight) sequences are given in Appendix A. An example of solidarity is given in Fig. 3 with 48% (non-equilibrium) true preference votes after three No-votes. An example of anger driven votes are the \(51\%\) No votes of the positive player in position 2 in Fig. 4 after a No vote of the positive player in position 1. For statistical inferences, however, we need a clear definition of such kind of “emotional responses.”

Definition 4

A node or information set is called a solidarity node or solidarity information set if

-

(i)

the positive (negative) player i whose turn it is has a predecessor with the same sign,

-

(ii)

a current number of previous Yes (No) votes is larger than zero \(z_{Yes}>0\) (\(z_{No}>0\)) and implies the equilibrium move No (Yes) by player i,

-

(iii)

the equilibrium move would have been Yes (No) for \(z_{Yes}-1\) (\(z_{No}-1\)).

If, in addition, \(z_{Yes}\) (\(z_{No}\)) is equal to the number of predecessors then the node is called a strong solidarity node, and otherwise a weak solidarity information set.

There are alternatives to these definitions. For example, a player may reduce incomplete information by the assumption that, in most cases, the voters from the other group had played equilibrium. Another possibility is to mitigate the third requirement by substituting prY-1 by prY-h where h is between 1 and the number of players from one’s own group. We think, however, that the restriction to prY-1 is that with the strongest signal: with one Yes-vote less, the equilibrium reply would have changed.

Definition 5

A node or information set of a player in position m is called an anger node or anger information set if

-

(i)

the positive (negative) player whose turn it is has a predecessor with the same sign

-

(ii)

the current number of previous Yes votes \(z_{Yes}<m\) (\(z_{No}<m\)) implies the equilibrium move Yes (No)

-

(iii)

the equilibrium move would have been No (Yes) for \(z_{Yes}+1\) (\(z_{No}+1\))

If, in addition, \(z_{Yes}\) (\(z_{No}\)) is equal to zero then the node is called a strong anger node, and otherwise a weak anger information set.

Strong solidarity or strong anger can be found in nodes, weak solidarity or weak anger in information sets. In the latter cases the current voter is not sure how the predecessors with the same sign have voted. Every game has seven separate nodes and three information sets with two nodes, i.e. in the eight different games (treatments times sequences), there are 80 different decision situations. 27 (34%) of them are classified as anger or solidarity nodes/information sets. In the regression analysis below, we find that, in these situations, there is a stronger tendency to deviate from equilibrium behavior than in other situations. Because several influences (position in the sequence, decision according or against true preferences) overlap, a regression analysis is better suited to investigate these "emotional responses" than non-parametric tests. In Section 4.6 we will test the following hypotheses with a regression analysis.

Hypothesis 1—Prevalence of true preferences: Deviations from equilibrium moves are more frequent in the direction of true preferences than away from true preferences.

Hypothesis 2—Emotional responses: Deviations from equilibrium moves are more frequent in solidarity and anger nodes/information sets than otherwise.

Hypothesis 3—Strong versus weak: Deviations from equilibrium moves are larger in strong solidarity (anger) nodes than in weak solidarity (anger) information sets.

Hypothesis 4—In dubio pro reo: Deviations from equilibrium moves are larger in solidarity information sets than in anger information sets.

All four hypotheses are evaluated jointly as regression parameters in our overall results predicting Yes versus No votes. Appendix D reports non-parametric tests concerning these individual hypotheses. The last hypothesis states that, in doubt (in information sets) we tend to believe that our co-player with the same sign has acted nicely.

4.5 Emotional evaluations

Emotions are influenced by others’ and own decisions in the process of a game and by the (anticipated or experienced) final result. In the previous sub-section, we investigated hypothetical emotional responses in certain states of the game—usually not the final state. In the experiment subjects were asked to self-evaluate their emotions after each game (round) according to their perceived happiness, anger, and fairness. Are the hypothetical emotions reflected by the subjectively reported emotions? Table 5 shows that, in strong anger situations, costly retaliation helps to decrease anger and to increase the perceived satisfaction as well as fairness. In other cases, also the decisions of later acting players and the result of a game may play a decisive role. This supports the assumption of emotion venting (e.g., Dickinson and Masclet 2015): After taking revenge, anger dwindles and satisfaction increases.

While emotional responses are defined for situations where previous players put the current player into a pivot player situation or not, you may look back from the end of the game and ask whether your decision has been decisive, i.e. whether it turned out ex post that you have been a pivot player or not. It might be satisfactory to have made the reward maximizing decision and you might feel anger if not. Three significant regularities are observed:

-

(i)

Wasted contributions: If players of my own sign have contributed less than \(k-1\) Yes votes (positive players) or \(4-k-1\) No votes (negative players) then my emotions are worse if I have followed true preferences instead of deciding opposite to them.

-

(ii)

Superfluous contributions: If there would have been enough votes for their preferred result, on average players regret their “solidarity decisions” but not as much as in (i).

-

(iii)

Pivot player contributions: If, in the end, players turn out to be pivot players they enjoy having made the reward maximizing decision.

The first two rows in Table 4 for \(T_1\) and for \(T_2\) support (i). Positive players feel worse if they voted Yes when compared to No (negative players vice versa). Differences between the fifth and the sixth row support (ii). The two middle rows of Table 4 for \(T_1\) and \(T_2\), support (iii).

Tables 4 and 5 seem partly contradictory, but note that in Table 4 the pivot player status is determined ex post and in Table 5 the status was expected. The relevant sets of decisions/emotions overlap but are largely different.

The structure of emotions does not seem to be much different between sequential and simultaneous votes. The overall level, however, is a bit more “pleasant” for sequential votes. On average, fairness and satisfaction are rated by 0.3 points higher and anger by 0.2 points lower. In simultaneous games, our subjects knew about their pivot situation only ex post, and the same applies for the subjects in positions 1, 2, or 3 in the sequential games. Therefore, it is difficult to connect their ex post emotions with their ex ante decisions. The pivot position (possibly the emotions) in the current round of simultaneous games influence, however, the behavior in the following round (Bolle and Otto 2020; Bolle and Spiller 2021).

4.6 Regression analysis

The significance of equilibrium behavior and deviations according to the proposed hypotheses are tested within a regression analysis. Instead of running separate regressions for positive and negative players, we assume that deviations from equilibrium are symmetric, and for negative voters only into the opposite direction of deviations by positive voters. Therefore, all variables indicating behavioral predictions have been transformed by multiplication with the sign of the respective player. The intercept and the dummy \(P^+\) for a positive player measures autonomous (asymmetric) tendencies for positive versus negative players to vote Yes. Equilibrium behavior (variable “predict”) has a higher weight for decisions in positions 3 and 4, but not in position 2 (confirming the conclusion from Table 7). In all regressions, the respective dummy term for strong backward induction (predict\(\times\)position 2) was never significant and it has therefore been dropped in the presented Table 6. Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4 are generally confirmed with one surprising exception, namely the coefficient of the weak anger dummy. Positive (negative) players in a weak anger situation are more probable to play equilibrium by voting Yes (No) than players in a no-anger situation. Our explanation is a more intensive decision process under the uncertainty whether or not a co-player with the same sign has “passed the buck,” thus making fewer mistakes when determining the equilibrium strategy. Otherwise Hypothesis 2 is confirmed. Generally strong hypothetical emotions cause a higher deviations from equilibrium than weak emotions, which is in favor of Hypothesis 3. The difference between the dummies for weak anger and weak solidarity is explained by “in dubio pro reo.” Hypothesis 4 is supported as the propensity to neglect solidarity in cases of doubt is far lower than the propensity to neglect anger. The significantly negative effect of the intercept is to be interpreted with caution. This aggregated residual reflects an overall tendency to deviate from the prediction into the direction No. In regressions which include \(P^+\), this strong tendency to vote No only holds for negative players, who are more likely to vote according to their true preference. The sum of intercept and the \(P^+\) coefficient depicts the tendency to follow true preferences for positive players. In the most differentiated regression, this sum is close to zero. With this differentiation, Hypothesis 1 is confirmed only for negative players. Furthermore, temporal influences over game repetitions have a significant effect, namely round (1–8) and period (1–32) negatively influencing the propensity to vote according to true preferences. \(T_1\) is only weakly significant. Other influences like the sequences of positive and negative players, reported emotions, or demographic variables (29 variables including personality questions not included in Table 6) are not significant. The only exception is Sequence 5 (\(+,+,+,-\)) potentially supporting an extreme form of solidarity or confirmative behavior (compare Fig. 4.

5 Conclusion

Contrary to most other investigations of sequential voting, the concern here is not incomplete information about the alternatives and the beneficial or harmful updating of beliefs of later voters based on the decisions of their predecessors. The central question is how voters cope with outside pressure (e.g. from party whips). Our model is based on complete information about ordinal preferences for sequential and cardinal preferences for simultaneous voting. Insofar, our investigation does not challenge any results of the incomplete information literature, but provides complementary results about an important aspect of voting.

The clear theoretical superiority of sequential over simultaneous voting is not confirmed in voting experiments where both procedures showed about the same frequency of true majority results. Reasons for deviating from the simple subgame perfect equilibrium strategy of sequential voting are, in addition to trembling hand errors, first, a strong reluctance or inability to perform backward induction. Second, there is an asymmetric tendency (concerning supporters and adversaries of a proposal) to deviate from equilibrium moves if it requires deciding in line with or against true preferences. Third, there are emotional non-equilibrium responses to the decisions of previous players with the same preferences (sign) who—by following the equilibrium strategy—passed the buck (shifted responsibility and costs forward) or not. The former states are called anger and the latter solidarity nodes or information sets. Deviation from equilibrium in anger situations means costly punishment of the other player(s) with the same sign. Both anger as well as solidarity warrant the same income as the foregone voter to whom the emotions are directed. Uncertainty about the votes of previous voters with the same sign completely prevents deviations from equilibrium (in dubio pro reo) in anger situations, but only partially in solidarity situations.Footnote 11

Sequential choices are often different from simultaneous choices due to positional advantages or disadvantages. Besides strategic considerations, social relations can play a role. It would not be that surprising if social preferences are transported by emotional reactions within the sequence of choices, with contingent reaction to previous choices in the sequence. In standard public good games there are no theoretical differences between sequential and a simultaneous mechanism, but in experiments strong behavioral differences are reported (Coats et al. 2009; Gächter et al. 2010; Bag and Roy 2011; Normann and Rau 2015). Also here social norms transported by emotions can strongly influence the results. The existence of behavioral differences between sequential and simultaneous mechanisms can be confirmed here for voting games as a special form of public good games (BTPG). A theoretical strategic advantage of first movers induces different emotional responses by the later players with the same sign, if this advantage is exploited as well as if foregone. This kind of anticipated sensitivity contradicts backward induction.

Our model with the central problem of outside pressure on voters completes the evaluation of sequential voting from the viewpoint of information aggregation. The main message here is twofold: be aware of structural differences but do not base your evaluations exclusively on theory. Our experimental investigation clearly illustrates this point and supports the existence of alternative social mechanisms being in place. Sequential voting behavior shows random but also systematic deviations from theory, which do not seem to be the exception but rather the rule.

Availability of data and material

Publicly available upon publication

Notes

Note that decisions in some cases are nearly simultaneous as for example voting by raising hands. In some cases voters might want to follow the majority or at least join a large enough minority to not stand alone. This avoidance strategy might lead to a largely unconscious bandwagon or domino effect.

In the US House of Representatives, yea-and-nay votes are obligatory for some decisions and, otherwise, require the support of 20% of the members being present. “Today, yea-and-nay votes almost invariably are cast by use of the electronic voting system. However, the speaker has the discretion under clause three of rule XX to have the clerk call the roll for the yeas and nays.” (From The US Government Publishing Office: “House Practice: A Guide to the Rules, Precedents and Procedures of the House.” Chapter 58. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-HPRACTICE-112/html/GPO-HPRACTICE-112-59.htm.)

One objection against this conclusion could be incomplete information concerning not only the true preferences of other voters, but also the “true state of the world” (i.e., the complete consequences of passing a proposal). Feddersen and Pesendorfer (1999) investigate a model without opportunity costs of voting, but with asymmetric information about the voters. Battaglini (2005) assumes voting costs and information cascades in sequential voting. In both models information aggregation is the central topic. Only sequential voting can transfer information about both issues. Information aggregation over actual preferences and true consequences is not possible under simultaneous voting and, therefore, sequential voting again seems to be preferable. A possible disadvantage might be a trend setting instead of information enhancing effect initiated by first votes, for example in US primaries, which led to legal disputes about the admissibility of sequential voting (see Morton and Williams 1999). Trend setting (or momentum) has been investigated by Dekel and Piccione 2000 and Ali and Kartik 2006.

The only other experimental comparison of simultaneous versus sequential voting we know of is Morton and Williams (1999), but there are no voting costs and the true preferences are identical for all voters. Only the voters’ information about the candidates differ. Dasgupta et al. (2008) report that sequential voting improves coordinating on the here for all more orifirable majority vote. Thus no conflict between players exists. Mago and Sheremeta (2019) find significant over-expenditures in sequential battles compared to simultaneous battles.

Applying equilibrium selection theory (Harsanyi and Selten 1988) to almost symmetric voting games, Bolle (2019) finds for low enough cost/benefit ratios that mixed strategy equilibria are played. For cost/benefit ratios converging to zero, equilibrium strategies converge to pure strategies where all players vote Yes if \(n^+\ge k\) and No otherwise. In an almost symmetric voting game, signs and magnitudes of costs and benefits may be different, but their ratio is the same for all players. With this understanding, our experimental games are almost symmetric.

In \(T_2\), according to the subgame perfect equilibrium, sometimes both positive players must vote Yes in order to guarantee the acceptance of the proposal. In \(T_1\), the first positive player can always free ride on the decisions of the following players. This would be the same situation for three negative players under \(k=2\).

Here the experimental behavior alone in simultaneous voting games is investigated in more detail. Two theoretically predicted invariances are confirmed, but the hypothesis of all players playing the same mixed strategy is clearly rejected. Many subjects play (almost) pure strategies. In an estimation of a finite mixture model with three types, the two types playing pure strategies cover 25–40% of the population. The other players follow the same mixed strategy with a probability between 0.43 and 0.55 which is close to 0.5 (simple heuristic) and 0.46 (equilibrium strategy). Below, we will report further results and compare, in particular, the frequencies of true majority results in \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) for \(k=2\) with those in the sequential voting.

Feddersen and Sandroni (2006) investigate voting with “ethical voters” who incur costs in order to be better informed, which can be considered as a social rule.

In the laboratory as well as in parliament, where voter position 3 has to vote against the party line or public opinion, she may feel left alone and may not be ready to excuse the non-solidarity behavior of her predecessor as simply rational.

In our experiments, incomplete information resulted from decisions elicited for every number of previous Yes votes. In roll call votes, it is known who voted Yes.

References

Ahmed AM (2007) Group identity, social distance and intergroup bias. J Econ Psychol 28(3):324–337

Ainsley C, Carrubba CJ, Crisp BF, Demirkaya B, Gabel MJ, Hadzic D (2020) Roll-call vote selection: implications for the study of legislative politics. Am Polit Sci Rev 114(3):691–706

Ali SN, Kartik N (2006) A theory of momentum in sequential voting. SSRN 902697

Bag PK, Roy S (2011) On sequential and simultaneous contributions under incomplete information. Int J Game Theory 40(1):119–145

Battaglini M (2005) Sequential voting with abstention. Games Econ Behav 51(2):445–463

Bellemare C, Kröger S, Van Soest A (2008) Measuring inequity aversion in a heterogeneous population using experimental decisions and subjective probabilities. Econometrica 76(4):815–839

Ben-Ner A, McCall BP, Stephane M, Wang H (2009) Identity and in-group/out-group differentiation in work and giving behaviors: experimental evidence. J Econ Behav Organ 72(1):153–170

Bolle F (2017) Passing the buck on the acceptance of responsibility. Res Econ 71(1):86–101

Bolle F (2018) Simultaneous and sequential voting under general decision rules. J Theor Polit 30(4):477–488

Bolle F (2019) When will party whips succeed? Evidence from almost symmetric voting games. Math. Soc Sci 102(C):24–34:

Bolle F, Otto PE (2020) Voting games: an experimental investigation. J Inst Theor Econ 176(3):496–525

Bolle F, Spiller J (2021) Cooperation against all predictions. Econ Inq

Bolton GE (1997) The rationality of splitting equally. J Econ Behav Organ 32(3):365–381

Clinton J, Jackman S, Rivers D (2004) The statistical analysis of roll call data. Am Polit Sci Rev 98(2):355–370

Coats JC, Gronberg TJ, Grosskopf B (2009) Simultaneous versus sequential public good provision and the role of refunds—an experimental study. J Public Econ 93(1):326–335

Dal Bó E (2007) Bribing Voters. Am J Polit Sci 51(4):789–803

Dasgupta S, Randazzo KA, Sheehan RS, Williams KC (2008) Coordinated voting in sequential and simultaneous elections: some experimental evidence. Exp Econ 11(4):315–335

Dekel E, Piccione M (2000) Sequential voting procedures in symmetric binary elections. J Polit Econ 108(1):34–55

Dickinson DL, Masclet D (2015) Emotion venting and punishment in public good experiments. J Public Econ 122:55–67

Downs A (1957) An economic theory of democracy. Harper, New York

Feddersen TJ, Pesendorfer W (1999) Abstention in elections with asymmetric information and diverse preferences. Am Polit Sci Rev 93(2):381–398

Feddersen TJ, Sandroni A (2006) Ethical voters and costly information acquisition. Q J Polit Sci 1(3):287–311

Feltovich N (2011) The effect of subtracting a constant from all payoffs in a hawk-dove game: experimental evidence of loss aversion in strategic behavior. S Econ J 77(4):814–826

Fischbacher U (2007) z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp Econ 10(2):171–178

Gächter S, Nosenzo D, Renner E, Sefton M (2010) Sequential vs. simultaneous contributions to public goods: experimental evidence. J Public Econ 94(7):515–522

Groseclose T, Milyo J (2010) Sincere versus sophisticated voting in congress: theory and evidence. J Polit 72:60–73

Groseclose T, Milyo J (2013) Sincere versus sophisticated voting when legislators vote sequentially. Soc Choice Welf 40(3):745–751

Harsanyi JC, Selten R et al (1988) A general theory of equilibrium selection in games. MIT Press, Cambridge (1)

Ido E, Roth AE (1998) Predicting how people play games: reinforcement learning in experimental games with unique, mixed strategy equilibria. Am Econ Rev 88(4):848–881

Kędzia Z, Hauser A (2011) The impact of political party control over the exercise of the parliamentary mandate. Inter-Parliamentary Union, Geneva

Kilgour D, Kirsner J, McConnell K (2006) Discipline versus democracy: party discipline in Canadian politics. In: Crosscurrents: contemporary political issues, pp 219–241

Kübler D, Weizsäcker G (2004) Limited depth of reasoning and failure of cascade formation in the laboratory. Rev Econ Stud 71(2):425–441

Mago SD, Sheremeta RM (2019) New Hampshire effect: behavior in sequential and simultaneous multi-battle contests. Exp Econ 22(2):325–349

Morton RB, Williams KC (1999) Information asymmetries and simultaneous versus sequential voting. Am Polit Sci Rev 93(1):51–67

Normann H-T, Rau HA (2015) Simultaneous and sequential contributions to step-level public goods: one versus two provision levels. J Confl Resolut 59(7):1273–1300

Ochs J (1995) Games with unique, mixed strategy equilibria: an experimental study. Games Econ Behav 10(1):202–217

Otto PE (2020) Decentralized matching markets of various sizes: similarly stable solutions with high proportions of equal splits. Int Game Theory Rev 22(4):2050005

Riker WH, Ordeshook PC (1968) A theory of the calculus of voting. Am Polit Sci Rev 62(1):25–42

Spenkuch JL, Montagnes BP, Magleby DB (2018) Backward induction in the wild? Evidence from sequential voting in the US senate. Am Econ Rev 108(7):1971–2013

Visser MS, Roelofs MR (2011) Heterogeneous preferences for altruism: gender and personality, social status, giving and taking. Exp Econ 14(4):490–506

Yan C, Li SX (2009) Group identity and social preferences. Am Econ Rev 99(1):431–57

Acknowledgements

We thank the two anonymous reviewers of Social Choice and Welfare for their valuable suggestions, which substantially helped to improve the presentation of the theoretical and experimental results as well as their interpretation.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was funded by the German Science Foundation (# BO747/14).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Not applicable.

Code availability

Publicly available upon publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Voting equilibria in the experimental cases

Two treatments (\(T_1\) with \(n^-=1\) and \(T_2\) with \(n^-=2\)) with \(n=4\), \(k=2\), and \(\rho =0.4\) are used to compare the experimental behavior in simultaneous versus sequential voting. According to Proposition 1, there is no pure strategy equilibrium in simultaneous voting. The symmetric mixed strategy equilibria of both cases are the same. Applying Eq. 3, we find two completely mixed equilibria: \(\pi _1 =0.464\) and \(\pi _2=0.218\). There are no asymmetric mixed strategy equilibria in this case (Bolle 2018). Regarding asymmetric pure/mixed strategy equilibria, it is a plausible requirement that the symmetric players (positive and negative) should play the same strategy.

Case \(n^-=1\) (\(T_1\)): In this game only the negative player can play a pure strategy. If she decides Yes, then the positive players have a unique mixed strategy, \(\pi =1-\sqrt{0.4}\), derived from Eq. 3 with \(n=3\), \(k=1\). \(\pi\) provides us with the negative player’s decisiveness \(q_i=0.441\). According to the second part of Proposition 2, the negative player’s strategy is confirmed, i.e., \(P^-\) voting Yes with certainty and the positive players voting Yes with \(\pi\) constitutes an equilibrium. If \(P^-\) decides Yes with \(Pr=0\), then the positive players’ mixed strategies are derived from Eq. 3 with \(n=3\) and \(k=2\) which results in \(\pi _{1,2}=0.5\pm \sqrt{0.05}\). For \(\pi _1=0.724\), the negative player’s decisiveness is \(q_i=0.165\). Therefore, because of part two of Proposition 2, this constitutes a further pure/mixed strategy equilibrium. For \(\pi _2=0.276\), we get \(q_i=0.434\) which according to Proposition 2, is not compatible with playing Yes with \(Pr=0\), i.e. this is not an additional equilibrium of the game.

Case \(n^-=2\) (\(T_2\)): If the two positive players play Yes with \(Pr=1\), then also the two negative players would do the same; if the two negative players play Yes with \(Pr=1\), then the two positive players would play No; but these are no pure strategy equilibria. Therefore, we can concentrate on the two remaining sub-cases. If either the positive or the negative voters play Yes with \(Pr=0\), then the remaining players’ mixed strategy is determined by Eq. 3 with \(n=2\) and \(k=1\). This implies \(\pi =0.6\) and the decisiveness of the pure strategy players \(q_i=0.288\). Therefore, only the equilibrium with the negative voters playing Yes with \(Pr=0\) and the positive players playing Yes with \(\pi =0.6\) exists.

For the simultaneous voting game the subgame perfect equilibria hold. Deviation from subgame perfect equilibria in the sequential voting behavior are denoted in Table 7 as of the percentage of participants. The first player (position 1) clearly shows higher deviation rates than the last player (position 4). The last players decision under certainty appear to be rather “simple”, while the second to last player already shows an increase in deviations by a factor between 1.5 to 2. The higher model fit for \(N^-\) in \(T_2\) and position 1 might be understood as avoiding costs under higher uncertainty if there is another player of the same type. Higher uncertainty at position 2 leading here to lower model fits.

Appendix B: General experimental instructions

1.1 B.1 Simultaneous voting game

These general instructions, here shown for symmetric numbers of player in \(T_2\), were handed out on a sheet of paper in the beginning, and were kept by the participants throughout the experiment. The general instructions were supplemented by on screen examples of all thresholds and questions asking which individual payments would result for various decisions of the players. The experiment started only after every player had understood the effects of the different sequences and answered all test examples correctly. Before each sequences the central changes were provided on the screen.

Welcome and thank you for participating in this study on group behavior. The session will last about one hour. Your payment will depend on your and your co-players’ decisions.

Please switch off your mobile phones and similar devices. The experiment is fully computerized. Please do not speak or otherwise communicate with your co-players during the experiment.

Following is a brief overview of the procedure. Please read this carefully. In the case of questions, please directly consult the investigator. After this introduction, you will have to answer some comprehension questions.

-

1.

In this experiment, you have to make decisions in several rounds.

-

2.

In every round, groups of four players are formed randomly. You always remain the same player. You are either player 1, player 2, player 3, or player 4. Your player number is shown on the screen.

-

3.

In every round, player 1 and player 2 receives 24 eurocents each. Player 3 and player 4 receives 60 eurocents each.

-

4.

Each player can choose either action A or action B.

-

5.

Action B is costless.

-

6.

Action A has different consequences: Player 1 and player 2 costs action A 24 eurocents. Player 3 and player 4 both receive for action A 24 eurocents.

-

7.

If a sufficient number of the four players have chosen action A, then player 1 and player 2 receive 60 eurocents. Player 3 and players 4 pay 60 eurocents.

-

8.

What the sufficient number for the special payment is, will be newly determined every 8 rounds and will always be shown on the screen.

The eurocents you earned are computed for every round according to the above rules and added up over all rounds. The final sum is your payment for your participation in this experiment, which you will receive individually directly after the experiment.

We start when everybody is ready.

1.2 B.2 Sequential voting game

These general instructions, here shown for symmetric numbers of player in \(T_2\), were handed out on a sheet of paper in the beginning, and were kept by the participants throughout the experiment. The general instructions were supplemented by on screen examples of all thresholds and questions asking which individual payments would result for various decisions of the players. The experiment started only after every player had understood the effects of the different sequences and answered all test examples correctly. Before each sequences the central changes were provided on the screen. A screenshot of the task in the sequential treatment is provided in Fig. 2.

Welcome and thank you for participating in this study on group behavior. The session will last about one hour. Your payment will depend on your and your co-players’ decisions.

Please switch off your mobile phones and similar devices. The experiment is fully computerized. Please do not speak or otherwise communicate with your co-players during the experiment.

Following is a brief overview of the procedure. Please read this carefully. In the case of questions, please directly consult the investigator. After this introduction, you will have to answer some comprehension questions.

-

1.

In this experiment, you have to make decisions in several rounds.

-

2.

In every round, groups of four players are formed randomly. You always remain the same player. You are either player 1, player 2, player 3, or player 4. Your player number is shown on the screen.

-

3.

In every round, player 1 and player 2 receives 24 eurocents each. Player 3 and player 4 receives 60 eurocents each.

-

4.

Each player can choose either action A or action B.

-

5.

Action B is costless.

-

6.

Action A has different consequences: Player 1 and player 2 costs action A 24 eurocents. Player 3 and player 4 both receive for action A 24 eurocents.

-

7.

If at least two out of the four players have chosen action A, then player 1 and player 2 receive 60 eurocents. Player 3 and players 4 pay 60 eurocents.

-

8.

The decisions of the players are done one after the other in a given order. For each possible combination of previous decisions, the action has to be stated. In the first position you have to decide between action A and action B. In the second position you have to decide between action A and action B for the case that the first player chose action A and for the case that the first player chose action B. In the third position there are three possible cases (so far zero, one or two times action A) and in the fourth position there are four possibilities (so far zero, one, two, or three times action A).

-

9.

The order changes every 8 rounds. The positions of first, second, third, or fourth player are always shown on the screen.

The eurocents you earned are computed for every round according to the above rules and added up over all rounds. The final sum is your payment for your participation in this experiment, which you will receive individually directly after the experiment.

We start when everybody is ready.

Appendix C: Static social preferences

The most often assumed static social preferences are linear altruism

and inequity aversion

In both approaches, we differentiate between ingroup and outgroup members. \(E_{same}\) is the income of the voters with the same sign and \(E_{other}\) is the income of the voters with the opposite sign (and the opposite goal). For altruism, it is plausible to assume \(b_i<a_i\) and that the sum of coefficients of same and other voters is smaller than 1; therefore \(b_i<1/(n-1)\). For inequality aversion, it is plausible that \(0<e_i<c_i<d_i<f_i\) and that the sum of coefficients for the case that i is advantaged is smaller than 1; therefore \(c_i<1/(n-1)\). Because of the experimental stranger design of the experiments, these preferences can be applied only to period income and not to accrued income.

For both types of social preferences, a voter who is not decisive would never incur costs; i.e. positive voters would not vote Yes and negative voters would not vote No. For altruism, the only effect is that i’s income decreases; for inequality aversion, because of \(c_i<1/(n-1)\), the value of (possibly) reduced inequality is smaller than the loss of income. For altruism with \(b_i>0.6\), a positive (negative) voter i who is decisive would vote No (Yes) in order to generate opportunity benefits for the voters with the opposite sign. But this relation violates the assumptions \(b_i<1/(n-1)=1/3\). Therefore, deviations from the behavior described by Proposition 3 can never be explained by altruism. Because of the assumption \(b_i<a_i\), this conclusion includes negative coefficients (spite). For inequality aversion, it is possible that a decisive voter i votes against true preferences. As also deviations of non-decisive voters are observed (Figs. 3, 4 in the next section), inequality aversion could only explain part of the observed deviations.

Appendix D: Emotional differentiation

Table 7 clearly illustrates the variations in deviation rates according to the position of the players within the sequential game. In particular, the player in position 4 followed considerably more often equilibrium moves than players in other positions. This effect has to be taken into account when evaluating behavior in nodes/information sets with possible emotional responses (Table 8). A hypothesis from Sect. 4.3 is supported, while equal deviation rates for the cases is rejected in a two-sided test. The tests are separated by the experimental treatment \(T_1\) and \(T_2\), and, given the strong influence of the position, by position 1-3 and position 4. Anger concerns deviations away from true preferences, and solidarity concerns deviations toward to true preferences, both with differing levels from weak to strong.

Hypothesis 1 (prevalence of true preferences) is tested by comparing deviations away from true preferences with deviations towards to true preferences in the non-emotional nodes/information sets, i.e. two middle rows “other away from” and “other toward” true preferences. In all three possible comparisons, the deviations to true preferences are more frequent, but the differences are not significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is not supported by the non-parametric tests.

Hypothesis 2 (emotional responses) is tested against the frequencies in the remaining category “other” (non-emotional responses). Nodes with strong emotions mostly show higher frequencies of deviations. In three of four cases the deviations from equilibrium are stronger showing significant difference in two cases. Also where the emotional response leads to a less deviations, this difference is significant. For weak solidarity, Hypothesis 2 receives support in one of the two cases. For weak anger the deviations are significantly lower. Concerning weak anger and solidarity together, only in three of six comparisons the frequency of deviations is higher than in the comparing category (one significant support and one significant rejection). Overall Hypothesis 2 is rejected with three supporting significances and two contradicting significant differences.

Hypothesis 3 (strong versus weak forms) is always significantly different in the three cases where the corresponding nodes and information sets exist in the data set, but significantly lower in weak than in strong in two and significantly higher in one. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is supported in two and rejected in one of the three possible comparisons.

Hypothesis 4 (in dubio pro reo) states that, in doubt about responsibility, people rarely punish and often reward their co-players with the same sign. In one of three comparisons, Hypothesis 4 is supported, in the other two not. Therefore, all four hypotheses are, if at all, only weakly supported by non-parametric tests.

Sequential voting decisions can be illustrated by game trees with respective frequencies of behavior at the different nodes or information sets, as subjects decided Yes or No for every number of previous Yes votes. In cases where the number of Yes votes is different from zero and different from the number of previous voters, the current decision maker does not know who of the previous players has voted Yes. Game trees with the frequencies of votes at the different nodes and information sets for two out of the eight sequences applied in the experiment are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. Anger and solidarity nodes or information sets are highlighted in color.

Game tree with decision frequencies for the sequence 1 (\(P_1^+,P_2^+,P_3^-,P_4^-\)) from \(T_2\). Note: \(P_i^{+(-)}\) denotes a positive (negative) voter in position i. Subgame perfect moves in bold lines. Broken lines indicate information sets. Percentages rest on 176 decisions by 22 subjects in the previous node/information set. Average total frequency of deviations from subgame perfect equilibrium is 27%. Blue denotes anger and green solidarity. There are no strong anger nodes and no weak solidarity information sets in this game tree

Game tree with decision frequencies for the sequence 5 (\(P_1^+,P_2^+,P_3^+,P_4^-\)) from \(T_1\). Note: \(P_i^{+(-)}\) denotes a positive (negative) voter in position i. Subgame perfect moves in bold lines. Broken lines indicate information sets. Percentages rest on 176 decisions by 22 subjects in the previous node/information set. Average total frequency of deviations from subgame perfect equilibrium is 28%. Dark blue colored nodes denote strong anger and light blue color denotes weak anger information sets. Green denotes solidarity. There are only strong solidarity nodes and no weak solidarity information sets in this game tree

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bolle, F., Otto, P.E. Voting behavior under outside pressure: promoting true majorities with sequential voting?. Soc Choice Welf 58, 711–740 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-021-01371-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-021-01371-6