Abstract

Actions can provide “responsibility utility” when they signal the actors’ identities or values to others or to themselves. This paper considers a novel implication of this responsibility utility for welfare analysis: fully informed incentive-compatible choice data can give a biased measure of the utility delivered by exogenously determined outcomes. A person’s choice of a policy outcome may be informed by responsibility utility that would be strictly absent if that same person were a passive recipient of that same policy outcome. We introduce the term “desirance” to describe a rank ordering over exogenously determined outcomes and present evidence that desirance captures the welfare consequences of exogenously determined outcomes more accurately than preference. We review literatures showing that preference is sensitive to contextual variations that influence responsibility utility and show experimentally that responsibility utility can explain discrepancies between welfare estimates derived from choice data and subjective well-being data. We close by discussing subjective well-being as a potential measure of desirance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

How should social planners allocate scarce resources? Should they subsidize health care? Or invest to protect the environment? Or support the local automobile industry by reducing taxes? Welfare economists often answer such questions with reference to the Kaldor–Hicks criterion which suggests that a policy is efficient and should be implemented if the gainers from the policy could potentially compensate the losers. To quantify utility gains and losses, welfare economists observe choices, reconstruct the underlying preferences from these choices, and use preference satisfaction as the welfare criterion. Using this choice-based approach to calculate utility gains and losses from policies assumes that the utility function that informs individual choices is the same utility function that informs the welfare people obtain from policies that the planner imposes on them. However, this might not always be the case. This paper considers the welfare implications of responsibility utility, which can incentivize people to choose an outcome other than that they would rather have imposed on them.

We are not the first to point out that, under certain circumstances, people choose outcomes other than those they would rather receive (e.g., Choshen-Hillel and Yaniv 2011); there is even an old joke on the subject.Footnote 1 The phenomenon has gone relatively unexplored in economics, however. This may be because there is no term in economics that captures the ranking of outcomes that people would rather receive, as distinct from those they would rather choose. We introduce that term: a desirance.Footnote 2 The difference between a desirance and a preference is that a desirance relation is defined over exogenously determined outcomes while a preference relation is defined over outcomes chosen by the agent. For example, someone who indicates that she would rather it rains tomorrow reveals a desirance (not a preference) for rain over dry weather. Systematic discrepancies across desirances and preferences are predicted, for example, in the literatures on signalling, self-signalling, warm glow, social pressure, regret, and delegation as reviewed in Sect. 2.2.

We identify one key source of the distinction between desirances and preferences as responsibility utility. Desirances are informed solely by what Loomes and Sugden (1982) call choiceless utility, which they define as “the utility that we would experience from an outcome if it were imposed on us” (Loomes and Sugden 1982, p. 807). As such, it is choiceless utility alone that determines the utility engendered by goods that are exogenously provided, e.g., as gifts, as externalities, or provided by policies. Whereas desirances are informed by choiceless utility alone, preferences are additionally informed by responsibility utility (though responsibility utility may take a value of zero). Responsibility utility is the utility that derives from being responsible for a choice.

We argue that responsibility utility and the difference between preferences and desirances have important implications for evaluating the welfare effects of policies. The distinction suggests that, in certain situations that can be identified ex ante, the revealed preference approach to welfare estimation is biased. The reason for this is that choices are partly informed by responsibility utility whereas responsibility utility cannot influence the utility people obtain from being subjected to an outcome, such as a policy. Hence, the relevant measure for evaluating which policy, if imposed on a population, would maximize utility is desirance, and not preference. We discuss the distinction between desirance and preference in detail in Part 1 of the paper and come back to the implications for welfare analysis in Sect. 3.4.

In Part 2, we suggest a way to measure choiceless utility and to elicit desirance rankings in practice. We first specify a non-responsibility criterion for the measurement of desirances. This criterion assumes that people cannot obtain responsibility utility from outcomes they are not responsible for. It requires that the subject whose ranking of outcomes is observed must believe that her ranking cannot influence the probability that any particular outcome is provided. We then discuss Subjective Well-Being (SWB) data, such as data on experienced affect and life satisfaction, as a measure for desirance. Unlike choice data from incentive compatible experiments, SWB data can fulfil the non-responsibility criterion and thus be used to calculate choiceless utility net of responsibility utility. This gain in conceptual precision may outweigh errors that result from hypothetical bias, i.e. the difference between answers people give to hypothetical questions compared to answers they give to questions with real consequences. We then suggest anticipated SWB as a generalizable means to elicit desirances and illustrate the use of anticipated SWB in an experiment.

We also show that responsibility utility and the difference between preferences and desirances can help organise and explain patterns in the literature. In particular, responsibility utility is one mechanism that can explain systematic discrepancies across anticipated SWB and choice, such as those reported in Benjamin et al. (2012, 2014). We consider how SWB measures might evoke differing levels of responsibility utility than choice procedures, which would cause choice trade-offs to differ from SWB trade-offs.

A related contribution is that our framework offers an empirical strategy to test whether responsibility utility explains anomalies and puzzles in the literature. As our experiment in Sect. 3.2 shows, we can use survey questions to recover measures of responsibility utility. In our data, this responsibility utility measure explains the discrepancy in rank order of outcomes across preference and desirance. This finding implies that our approach could be applied generally to test whether responsibility utility explains choice reversals. This empirical exercise could be useful when the goal is to extrapolate predictions and estimates from one specific choice context and apply them to others.

The concept of responsibility utility and the distinction between preferences and desirances relate to several literatures that discuss the way economists and other social scientists conceptualise utility. In the political economy literature (e.g., Morton et al. 2019; Robbett and Matthews 2018; Schuessler 2000; Spenkuch 2018), it is argued that “people obtain expressive utility, for example, by confirming pleasing attributes of being generous, cooperative, trusting or trustworthy, or ethical and moral” (Hillman 2010, p. 403). Expressive utility can potentially be delivered by any action—voting (Hillman 2010), responding to a survey (e.g., Bullock et al. 2015), and incentive-compatible market choices (e.g., DellaVigna et al. 2012) are examples. For precision, we coin the term responsibility utility to describe the subset of expressive utility that derives from being responsible for a choice. We separate it from other forms of expressive utility because responsibility utility has particular implications for welfare estimation that other forms of expressive utility do not.

Responsibility utility is also a subcomponent of what Frey et al. (2004) term procedural utility—the notion that outcomes deliver differing levels of utility depending on how they come about. The procedure by which the outcome comes about is decisive to responsibility utility: if the outcome is exogenously generated then responsibility utility is strictly zero. Our paper is also related to the distinction between decision utility and experienced utility made by Kahneman et al. (1997). Both approaches imply that the utility that informs choices can differ from the utility that informs welfare. However, in Kahneman et al. (1997) dissociations between choices (decision utility) and welfare (experienced utility) are the result of cognitive biases that lead agents to make decisions that do not maximise welfare (see also Sunstein 2007, 2020; Weimer 2017). Cognitive biases play no role in the current analysis. Responsibility utility can induce rational, fully-informed decision makers to choose outcomes other than those they expect would have maximised their utility had the outcomes been exogenously determined.

The remainder of the paper is structured in two parts. Part I reviews prior literature through the lens of our preference/desirance distinction. We present theory (Sect. 2.1) and evidence (Sect. 2.2) that a distinct utility function informs incentive compatible choice than informs a rank ordering over exogenously determined outcomes. Part II investigates which data might recover more accurate measures of the benefits delivered by exogenously determined outcomes. Section 3.1 suggests using SWB data to measure desirances, and Sect. 3.2 presents a short experiment illustrating that it is possible to measure desirances using anticipated SWB measures. Section 3.3 suggests that responsibility utility is one potential explanation for some key results reported in Benjamin et al. (2012, 2014) about differences across choice and anticipated SWB data. Section 3.4 concludes by discussing the policy-implications of our preference/desirance distinction suggesting that sometimes measures of desirances, rather than preferences, should be used in welfare analyses.

2 Part I: Prior theory and existing evidence

2.1 Responsibility utility, choiceless utility, preference, and desirance

Since the “mathematical revolution” in economics (Pareto 1971; von Neumann and Morgenstern 2007; Arrow 1950; Samuelson 1954), economists have inferred preference from what is revealed in choice. A dominant view is that it is meaningless to speak of a “preference” unless that preference is observed in choice (e.g., Gul and Pesendorfer 2005; Bernheim and Rangel 2009). A consequence of this view is that incentive-compatible choices enjoy a uniquely privileged position as valid data for welfare analysis in welfare economics where preference satisfaction is used as the welfare criterion. In this paper, we show that incentive-compatible choice data can provide biased measures of welfare when policy outcomes are exogenously determined.

People’s choices of outcomes are often informed by feelings of being responsible for the outcomes. However, this responsibility utility is strictly absent if the same individuals were passive recipients of those same outcomes. Hence, the utility function that informs people’s choices can differ from the utility function that informs people’s welfare when the outcomes are exogenously-determined, and choice data can give a misleading measure of the benefits received from some policies.Footnote 3 The appropriate welfare measure when outcomes are exogenously determined is thus not the satisfaction of preferences as revealed by choice. Instead of preferences, a rank-ordering over exogenously provided outcomes is needed. Yet there is no term we know of in economics to describe such an ordering in terms of expected utility over exogenously determined outcomes. We introduce the term “desirance” for this purpose.

2.1.1 Desirance

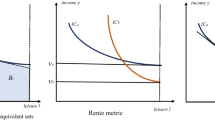

A desirance describes a ranking of alternatives based on their relative choiceless utility. Choiceless utility is the utility that an individual would derive from an outcome “if he experienced it without having chosen it. For example, he might have been compelled to have x by natural forces, or x might have been imposed on him by a dictatorial government” (Loomes and Sugden 1982, p. 807, italics theirs).Footnote 4 For illustrative purposes, let \({U}^{CL}\left(x,y\right)\) describe the choiceless utility that an individual derives from receiving an outcome that consists of two goods \(x\) and \(y\). Assuming a Cobb–Douglas utility function, choiceless utility is given by \({U}^{CL}={x}^{\alpha }{y}^{1-\alpha }\). As usual, the tradeoffs between the two goods in terms of choiceless utility can be described by the slope of the indifference curve, i.e., \(-\frac{dx}{dy}=-\frac{\alpha }{1-\alpha }\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)\), for a constant level of choiceless utility. The dotted line in Fig. 1 depicts the iso-desirance curve that charts all combinations of goods \(x\) and \(y\) that deliver some constant level of choiceless utility. The individual has a desirance for all \((x,y)\)-bundles of the goods \(x\) and \(y\) above this curve over the \((x,y)\)-bundles on or below this curve.

Indifference curves implied by preferences and desirances in a case where choosing \(x\) delivers positive responsibility utility and choosing \(y\) delivers zero responsibility utility. The parameters used are \({U}^{CL}\left(x,y\right)=100, {U}^{A}\left(x,y\right)=150,\alpha =0.4,\) and \({r}_{x}=0.5\)

2.1.2 Responsibility utility

Responsibility utility is the utility that an individual derives from choosing an outcome. It is recognised, for example, when we speak of people feeling ashamed, guilty, regretful, embarrassed or proud of their decision to take some specific action. To the extent that people value feeling such positive emotions or seek to avoid these negative feelings, responsibility utility will inform preferences (see Sect. 2.2 for more examples of sources of responsibility utility).

Responsibility utility is positive if an agent wants to be responsible for an outcome and it is negative if the agent would rather not be responsible for it. More specifically, we suggest that responsibility utility is a function of how good (or how bad) an agent feels about being responsible for an outcome and how responsible that agent feels for bringing about the outcome. Later we model responsibility utility as the interaction of these two dimensions so that responsibility utility is zero if either dimension takes a value of zero i.e., if the agent feels neither good nor bad about being responsible for the outcome or if the agent does not feel at all responsible for the outcome.Footnote 5

2.1.3 Preferences and desirances

Like desirances, preferences for an outcome consisting of goods \(x\) and \(y\) are also informed by choiceless utility \({U}^{CL}(x,y)\). Additionally, however, preferences are informed by the responsibility utility \(r(x,y)\) that an individual derives from choosing an outcome. By definition, choiceless utility is independent of one’s role in bringing about the outcome, whereas responsibility utility is entirely determined by one’s role in bringing about the outcome. Hence, we will assume that choiceless utility and responsibility utility are additively separable. We refer to the sum of choiceless utility and responsibility utility as “agentic utility” \({U}^{A}\left(x,y\right)={U}^{CL}\left(x,y\right)+r(x,y)\), because a prerequisite for responsibility utility to enter the utility function is that the agent has agency over the outcome of the choice. Table 1 presents a simple summary of how desirance differs from preference.

To illustrate how responsibility utility can lead to differences between preferences and desirances, let us assume that choosing one unit of good \(x\) delivers responsibility utility of \({r}_{x}\) and that choosing good \(y\) does not provide any responsibility utility (\({r}_{y}=0)\) so that \(r\left(x,y\right)={r}_{x}x\). We assume \({r}_{x}\) to be a constant parameter so that deciding for one unit of \(x\) provides \({r}_{x}\) responsibility utility independent of the amount of \(x\) already chosen.Footnote 6 Assuming a Cobb–Douglas utility function for choiceless utility as above, the agentic utility of deciding for (and consuming) outcome \((x,y)\) is \({U}^{A}\left(x,y\right)={x}^{\alpha }{y}^{1-\alpha }+{r}_{x}x\). The slope of the indifference curve corresponding to this agentic utility is \(-\frac{dx}{dy}=-\frac{\alpha }{1-\alpha }\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)-\frac{{r}_{x}}{\left(1-\alpha \right)}{\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)}^{\alpha }\) for a constant level of agentic utility. As such, with positive responsibility utility for choosing good \(x\) (\({r}_{x}>0\)) and zero responsibility utility for choosing good \(y\), at every level of x the iso-preference curve is steeper than the iso-desirance curve. The iso-preference curve for this case is presented in the solid line in Fig. 1.

Figure 1 illustrates that preferences and desirances can differ. It also shows that the iso-preference curve and the iso-desirance curve can cross each other. As a result, a \((x,y)\)-bundle that is more preferred to another is not necessarily more desired. For example, the consumption bundles represented by points \(A\) and \(B\) are both feasible, but the consumer has a desirance for \(A\) over B and a preference for \(B\) over \(A\). Given the choice, the consumer would choose B over A. In a world of exogenous allocations, the same consumer would be better off receiving A than B. If a (policy) change from \(A\) to \(B\) were imposed on the consumer, the increase in consumption of \(x\) would not compensate for the reduction in consumption of good \(y\) even though the same consumer would choose B over A.

Figure 2 illustrates a case in which \(x\) provides negative responsibility utility, i.e., where \({r}_{x}\) is negative, and where \(y\) does not provide any responsibility utility as before. Since in this illustration \(x\) provides choiceless utility at a decreasing rate and responsibility utility is constant (and negative) for each chosen unit of \(x\), choosing \(x\) becomes utility-decreasing at the point when the negative responsibility utility of choosing \(x\) equals the positive choiceless utility of consuming \(x\). As a result, the indifference curve will eventually slope upwards, indicating that the “good” \(x\) becomes a bad. People would enjoy consuming more of \(x\) but they would not choose more of x because they do not want to be responsible for having chosen more of it (e.g., for reasons of signalling or guilt avoidance).

Indifference curves implied by preferences and desirances in a case where choosing \(x\) delivers negative responsibility utility and choosing \(y\) delivers zero responsibility utility. The parameters used are \({U}^{CL}\left(x,y\right)=100, {U}^{A}\left(x,y\right)=71,\alpha =0.4,\) and \({r}_{x}=-0.5\)

2.1.4 Predictions

Taken together, the foregoing gives rise to five predictions about choosing and consuming an outcome which consists of two goods \(x\) and \(y\). The first two predictions concern the causes of responsibility utility as summarised in Sect. 2.1.2 and the following three concern the consequences of responsibility utility as illustrated in the indifference curve analysis described in Sect. 2.1.3.

Prediction 1

Increasing how good an agent feels about being responsible for choosing an outcome will increase the responsibility utility derived from choosing that outcome. Hence, ceteris paribus, it will increase preference for the outcome over other outcomes. It will not change the choiceless utility of the outcome nor the desirance for the outcome over other outcomes.

Prediction 2

Increasing how responsible an agent feels for bringing about an outcome will increase the responsibility utility derived from choosing the outcome. Hence, ceteris paribus, it will increase the preference for the outcome if the agent feels good about being responsible for the outcome, and it will decrease the preference for the outcome if the agent feels bad about being responsible for the outcome. It will not change the choiceless utility of the outcome nor the desirance for the outcome over other outcomes.

Prediction 3

As responsibility utility increases in absolute size, so too will the discrepancy between preference and desirance increase.

Prediction 4

Allowing people to choose between two outcomes can alter the rank ordering of those outcomes. An intervention that grants choice where previously there had been no choice has the effect of shifting the optimal consumption bundle from a point on the iso-desirance curve (e.g., point A in Fig. 1) to a point on the iso-preference curve (e.g., point B in Fig. 1).

Prediction 5

This prediction assumes that goods can be characterised by their attributes. If a good has an attribute that provides responsibility utility, changing the level of this attribute influences rank orderings differently in preference than in desirance. If the attribute gives responsibility utility to the good and choiceless utility to the good of the same sign (e.g., if an attribute gives positive choiceless utility to good \(x\) and positive responsibility utility to good \(x\) so that the iso-preference curve is steeper than the iso-desirance curve as in Fig. 1), then the attribute will be more predictive of preference than of desirance. Where the attribute gives responsibility utility and choiceless utility that differ in sign, the iso-preference curve will be less steep than the iso-desirance curve, and the attribute will be less positively predictive of preference than of desirance and may become negatively predictive of preference (e.g., Fig. 2).

The first two predictions about the causes of responsibility utility assume that we know whether being responsible for an outcome is anticipated to provide utility gains or losses. We can often rely on prior theory and experimental evidence to establish the valence of responsibility utility. We can also measure responsibility utility using self-report measures, as demonstrated in Sect. 3.2. The next section reviews literatures and specific results that relate to the predictions above.

2.2 Sources of responsibility utility

Manifestations of responsibility utility can be identified throughout the social sciences. For instance, theories on signaling and regret share the prediction that someone might choose an outcome that differs from the outcome she would rather receive. Prima facie, there is little overlap in these literatures: signaling is a public and instrumental behaviour whereas regret is a private, hedonic response. One contribution of the responsibility utility framework is that it explains and systematizes a broad range of decisions.

The goal of this section is to present examples that offer experimental evidence directly related to our Predictions 1 and 2 from Sect. 2.1.4. Each study below manipulates a feature of the decision-making context that influences either how responsible agents feel or how good they feel about being responsible. It is not the goal of this section to present an exhaustive list of literatures that imply that being responsible for an outcome delivers utility, but merely to present some salient examples that relate to our predictions.

2.2.1 Social pressure

In some cases, social pressure can cause individuals to choose outcomes they would rather not receive. For example, in Sah et al. (2013) choosers reported that outcome A was more attractive than outcome B, indicating a desirance for outcome A. Yet a majority chose B, indicating a preference for outcome B. They did so because they felt pressure to comply with the recommendation of an advisor who had an interest in recommending option B. This mechanism is revealed in two survey items that measured the responsibility utility associated with choosing option B: how uncomfortable the chooser would have felt turning down the advisor’s recommendation and how much the chooser wanted to help the advisor.

More generally, social pressure adds to the burden of responsibility one feels when making a choice: it intensifies how good/bad it feels to be responsible for a given outcome. Prediction 1 is that this increases responsibility utility. The specific prediction is that people who anticipate negative consequences from deviating from the choice recommended by social pressure will shift their preference towards whichever outcome is recommended by the group. Their desirance, however, will remain unaffected by social pressure.

2.2.2 Signalling

Individuals feel better about being responsible for outcomes when that responsibility sends positive signals to others regarding their character and values. For example, being responsible for a donation to a charity can signal to others that one is a generous person. This source of positive responsibility utility is eliminated if the donation is confidential: there is less reason to care about giving the impression of being generous if nobody can observe whether or not we acted generously. In line with Prediction 1, a recent study shows that the preference to donate is lower when donations are confidential than when they are publicly observable (Samek and Sheremeta 2017).

2.2.3 Regret

We regret decisions, not outcomes. As such, anticipated regret will influence preferences but not desirances. For example, van de Ven and Zeelenberg (2011) offered subjects a chance to swap an initial ticket they had been allocated in a lottery for another ticket and a pen. Since the new ticket was just as likely to win as was the old ticket, the pen was pure surplus, and so swapping delivered a gain in choiceless utility. Yet, over a third of subjects chose not to swap. We explain this result with reference to our Prediction 1. Knowing that we might receive negative feedback increases how bad it feels to be responsible for that outcome. The experiment tested that prediction because it manipulated whether the tickets that were initially assigned to participants were in an envelope. Subjects in the no envelope condition could see the number of the ticket they were initially allocated and so knew that swapping brought with it the possibility of learning that the initial ticket won the lottery. Those in the envelope condition could not receive this negative feedback. Hence swapping entails more negative responsibility utility (in the form of anticipated regret) for the no envelope group than the envelope group. In our interpretation, this greater negative responsibility utility caused subjects in the no envelope condition to be less likely to swap than those in the envelope group.

2.2.4 Delegation

Individuals can reduce feelings of responsibility by delegating a decision to another person or decision-making device such as an algorithm. The phenomenon of “algorithm aversion” (Dietvorst et al. 2015) might be explained by people’s wishes to obtain some responsibility utility from choosing themselves (Bobadilla-Suarez et al. 2017). Delegation is also an attractive solution to some dilemmas. For instance, in a dictator game the dictator might desire keeping the endowment but may anticipate guilt, i.e. negative responsibility utility, from following through on that desire (see Fig. 2 for an illustration). Hamman et al. (2010) introduced intermediaries into a dictator game. These intermediaries advertised to dictators how much of the dictators’ endowment they would pass on to the recipient and, on that basis, dictators chose which intermediary to use. Dictators assigned to the intermediary condition reported lower ratings of responsibility for the payment to the recipient than did dictators in a standard game. In line with Prediction 2, which stated that responsibility utility decreases as feelings of responsibility decrease, they also split less with recipients than did dictators in a standard game.

2.2.5 Warm glow, self-signalling and impure altruism

Many individuals are altruistic and derive benefits from others’ positive outcomes (e.g. Gintis 2009).Footnote 7 In addition, people generally enjoy a good feeling from being responsible for benefiting others (Aknin et al. 2009; 2013), which is termed warm glow (Andreoni 1990). Another source of responsibility utility that derives from acting virtuously (and hence is also difficult to distinguish from altruism) is self-signalling. Many people derive utility from thinking of themselves as decent and will act to bolster that view of themselves if it is inexpensive to do so (Bodner and Prelec 2003).

A study by Choshen-Hillel and Yaniv (2011) attempts to unpack pure altruism from expressive motivations. The study had subjects rank two compensation schemes: an equal scheme, where another participant to the study would be paid the same as the subject, or a pro-social scheme, where the other participant would be paid more than the subject. The study manipulated whether subjects ranked the compensation schemes by choosing one or by answering which scheme would make them more satisfied if it were to come about through an exogenous process. The design of this study speaks to our Prediction 4, which posits that merely granting agency over an outcome can alter rank-orderings in terms of expected utility. Choshen-Hillel and Yaniv (2011) found that a smaller proportion of study participants desired the pro-social compensation scheme than chose it.Footnote 8

3 Part II: Implications for welfare measurement

3.1 Towards a measure of desirance and choiceless utility

In what follows, we start from the premise that there are circumstances in which a policymaker wishes to measure which of two alternative policies, if imposed on the population, would maximize the utility of that population. According to the conceptual framework set out in Sect. 2.1.1, the appropriate measure for this task is a desirance. As evidenced by the empirical results set out in Sect. 2.2, using preference measures instead of desirance measures could bias the policymaker’s conclusions. The remainder of the paper considers the practicalities of measuring desirance.

3.1.1 The non-responsibility criterion

To elicit choiceless utility alone, it must be that there is no scope for responsibility utility to enter the utility function. We refer to this as the non-responsibility criterion. To see how difficult it is for a procedure to meet the non-responsibility criterion, consider the following scenario. Imagine we have a survey respondent from whom we wish to elicit a desirance ordering over goods \(x\) and \(y\) and that we ask the respondent the following question: “The State is deciding which of goods \(x\) and \(y\) to impose on the community. Please indicate which good would give you more utility if it were to be imposed on you by the State.” Even though the question asks for a desirance ordering, the answer that is elicited might well be a preference ordering. This will happen if the respondent believes that indicating good \(x\) increases the probability that the state imposes good \(x\); this belief that her response might make her partially responsible for whichever good is provided is a sufficient condition for responsibility utility to influence her response. To elicit a desirance then, we need an elicitation procedure that the respondent believes cannot influence the likelihood that a given outcome is realized. This is the non-responsibility criterion.Footnote 9

3.1.2 Trading-off hypothetical bias with bias induced by responsibility utility

Any measure that fulfils the non-responsibility criterion cannot rely on an incentivized procedure because any incentivized elicitation method, such as a Becker-deGroot-Marschak mechanism or observed choice, relies on consequential choices. The currently dominant view in welfare economics is that incentive-compatible choice is more precise and less prone to bias than unincentivized ratings as an indicator of welfare (Bernheim and Rangel 2009; Gul and Pesendorfer 2005). Welfare economists are often worried that hypothetical bias is too strong to rely on unincentivized procedures when making policy evaluations and recommendations (e.g., Hausman 2012).Footnote 10 However, stated preference measures that are hypothetical have become influential in informing policy making, especially in domains such as the evaluation of environmental goods (Atkinson et al. 2018).

Whenever there is a need to measure choiceless utility uncontaminated by responsibility utility, the welfare economist faces a dilemma. Should she be more worried about the hypothetical bias of unincentivized procedures or the bias created by responsibility utility when using preferences to measure desirances? We suggest that this is a positive question and not a normative one. The welfare economist should seek to minimize bias, regardless its source. There may exist circumstances in which an unincentivized desirance measure delivers a less biased measure of utility than an incentivized choice. This will happen whenever responsibility utility imposes a bias that is larger than hypothetical bias. Future research is needed to investigate the circumstances in which this occurs.

3.1.3 Experienced Subjective Well-Being (SWB)

There is an existing welfare measure that under specific circumstances can fulfil the non-responsibility criterion, namely experienced SWB, e.g. life satisfaction. Recall the definition of choiceless utility: “the utility that we would experience from an outcome if it were imposed on us” (Loomes and Sugden 1982, p. 807). Imagine that an outcome that was exogenously imposed on a population is reliably demonstrated to cause a change in SWB. The observed change in SWB cannot measure responsibility utility because an exogenously-imposed outcome cannot deliver responsibility utility and so it can only be picking up the choiceless utility delivered by the outcome. Some examples of exogenously imposed outcomes that have been valued using SWB measures include the relative costs of inflation and unemployment (Di Tella et al. 2001), the impact of the Chernobyl disaster (Berger 2010), and the negative externality induced by a neighbour’s wage (Luttmer 2005). If policy makers are interested in the net benefits delivered by the imposition of these outcomes on a population, then it follows that SWB data is conceptually more appropriate for this analysis than is choice data.Footnote 11

While experienced SWB data delivers information about desirances when comparing situations that differ only in exogenously imposed outcomes, experienced SWB data can also provide data on agentic utility when comparing outcomes that people have chosen themselves. The SWB question “how satisfied are you with your life, all things considered?” invites respondents to step back and consider the story of their life (Baerger and McAdams 1999; Steptoe et al. 2015). It invites respondents to consider the responsibility utility they derive from the choices that have brought them to this point, in addition to considering the choiceless utility they derive from living their lives. Experienced SWB data can deliver measures of the agentic utility derived from chosen outcomes as well as measures of the choiceless utility derived from exogenously imposed outcomes.

A number of practical considerations limit the degree to which experienced SWB can be used as a measure of choiceless utility. First, the goods in question must always be exogenously provided; otherwise experienced SWB might include the responsibility utility engendered by having chosen the good. Second, the goods must already exist; otherwise their impact on experienced SWB cannot be observed. Third, there must be as-good-as-random variation in the level provision of the goods; otherwise their causal impact on experienced SWB cannot be estimated. Since it is rare that all these conditions are satisfied, an alternative measure of desirances is needed.

3.2 Measuring desirances using anticipated Subjective Well-being

A leading candidate for a generalizable measure of desirances is anticipated SWB. Questions of the type used in Choshen-Hillel and Yaniv (2011), such as “Which would make you more satisfied if you were to receive it through random assignment?” fulfil the non-responsibility criterion and can be used to evaluate any good, even those that do not yet exist. In this section, we show that anticipated SWB measures can be used to measure desirances. Future research will have to quantify the trade-offs between the hypothetical bias that unincentivized procedures such as anticipated SWB measures induce and the bias resulting from disregarding responsibility utility. Here, we present a simple experiment to illustrate that it is possible to measure preferences and desirances and compare them to each other using anticipated satisfaction data. The section also illustrates that is it possible to measure responsibility utility and to test whether it explains differences between preferences and desirances.

3.2.1 Background and predictions

The study by Choshen-Hillel and Yaniv (2011) reported in Sect. 2.2.5 elicited desirance by asking participants to rank anticipated satisfaction and elicited preference by a different elicitation method (choice). To deliver an uncontaminated comparison of preference and desirance, we need the elicitation method to be constant. Hence, we conducted an experiment that modified the design of Choshen-Hillel and Yaniv (2011) and elicited both preference and desirance for a higher or lower payment to another participant using anticipated satisfaction. Specifically, we randomly assign participants to either a non-agentic condition that asks which outcome would make you more satisfied if it were randomly generated or an agentic condition that asks which outcome would make you more satisfied if you were to have chosen it. Additionally, we use three survey items to measure each participant’s responsibility utility.

We can apply predictions we presented in Sect. 2.1.4 to this experiment. Prediction 3 suggests that as responsibility utility increases in absolute size, so too will the discrepancy between preference and desirance. Hence, adding responsibility utility to our regressions should render the difference between agentic and non-agentic measures insignificant, suggesting that the discrepancy across choice and non-agentic procedures is explained by responsibility utility. Prediction 4 suggests that an intervention that grants choice can alter the rank ordering of outcomes relative to a no-choice situation. As such, respondents’ rankings of outcomes should differ across the agentic and the non-agentic conditions in our experiment. Prediction 5 suggests that agentic (vs. non-agentic) rankings place more positive weight on attributes that deliver positive responsibility utility. In our experiment, the relevant attribute with positive responsibility utility is “payment to the other participant”, where we assume that a positive payment to the other participant provides positive responsibility utility via warm glow or self-signalling. As such, relative to those in the non-agentic condition, respondents in the agentic condition should favour the pro-social outcome.

3.2.2 Participants

We conducted the experiment through Amazon Mechanical Turk where it was advertised as a “ten minute survey for academic research” and as paying $0.35. The informed consent page told the respondents that “we are interested in your preferences” but gave no further specifics on the survey content. Given concerns about data quality from Amazon Mechanical Turk (e.g. Chmielewski and Kucker 2020), we employed an instructional manipulation check that contained text buried within the question instructing respondents to click the fourth option to demonstrate that they had read the question (Oppenheimer et al. 2009). Between March 8th and 11th 2018, we recruited 332 respondents, 203 of whom passed the instructional manipulation check. Of these 203 participants, 103 were randomly assigned to be “participant B” who would passively receive the payment that is the focus of the current study. The dependent variable was not elicited from those 103 respondents and they were not aware of the fact that they might receive an extra bonus depending on other participants’ answers. The remaining 100 survey respondents are the subjects of our analysis (Mage = 35; 40% female).

3.2.3 Materials

At the close of an unrelated survey, we explained to our 100 subjects that they had been matched with another participant (Participant B). We asked our subjects which of two outcomes would lead them to be more satisfied—if participant B were paid the same as them ($0.35, equal compensation), or if participant B were paid more ($0.50, pro-social compensation). Table 2 displays the relevant questions and answers in the order that subjects encountered them.

Our subjects were randomly assigned to either a non-agentic condition (n = 51) to elicit a desirance, or to an agentic condition (n = 49) to elicit an agentic satisfaction ranking and, ultimately, a choice. The non-agentic condition told subjects that the other participants’ compensation would be determined by a random process. The agentic condition told subjects that on a later screen they would determine the level of compensation for the other participant, and asked whether they would be more satisfied if the other participant were paid $0.35 “because of your choice” or $0.50 “because of your choice”. The decision about the level of compensation for the other participant was consequential—we did match other participants with subjects and, if matched to a subject in the agentic condition, paid them in accordance with the choice made by that subject. For those matched to participants in the non-agentic condition, we randomly assigned a bonus of $0.15 to half so that they were paid $0.50 instead of $0.35. Of course, we could not make the desirance elicitation consequential because doing so would have breached the non-responsibility criterion.

On the screen after subjects had indicated which outcome would make them more satisfied, we asked three questions to measure their responsibility utility. We asked subjects how good they would feel about themselves for paying the other participant $0.35 (virtue35) and how good they would feel about themselves for paying the other participant $0.50 (virtue50) on 5-point Likert scales from “bad” to “good”. We also asked subjects how responsible they felt for the other participant’s payment on a 5-point Likert scale from “not responsible at all” to “entirely responsible”. We modelled the responsibility utility of a pro-social payment for each subject as the product of how responsible she felt for the payment (on a scale from 0 to 4) and of how much better it felt to pay the pro-social compensation than to pay the equal compensation (on a scale from 4 to − 4). Hence, our responsibility utility measure is calculated as Responsibility utilityprosocial = How responsible × (virtue50 − virtue35) and can take on values between − 16 and + 16.

3.2.4 Results

The probability of ranking the pro-social compensation as giving greater satisfaction is 73 percent in the agentic condition and 53 percent in the non-agentic condition (p = 0.034, see Model 1 of Table 3), which suggests that non-agentic and agentic SWB measures produce different rankings.Footnote 12

Our manipulation made subjects in the agentic condition responsible for the outcome that the other participant received and explicated that whichever payment the other respondent received would be “because of your choice”. This manipulation had the intended effect: subjects in the agentic condition gave higher ratings in response to the follow-up question how responsible do you feel for the other participant’s payment than did those in the non-agentic condition (M = 3.18 vs. M = 2.22, t = 4.34, p < 0.001).Footnote 13 As a result, the responsibility utility of making the pro-social payment was higher in the agentic condition than in the non-agentic condition (M = 3.45 vs. M = 0.98, t = 2.30, p = 0.024).

We also asked the 49 subjects in the agentic condition to choose whether participant B would get the lower or the higher payment. The overwhelming majority of these consequential choices (46 of 49) were in line with subjects’ agentic SWB ratings in the sense that they chose the payment they had ranked higher in answer to the satisfaction question.Footnote 14 For instance, thirteen respondents had ranked the $0.35 payment to payer B as giving greater satisfaction than the $0.50 payment and twelve of these chose to pay $0.35. Vice versa, thirty-six respondents had ranked the $0.50 payment to payer B as giving greater satisfaction than the $0.35 payment and thirty-four of these chose to pay $0.50.

Model 2 tests whether responsibility utility explains the agentic/non-agentic discrepancy. It finds that responsibility utility is highly predictive of rating the pro-social payment as giving greater satisfaction (z = 3.85, p < 0.001) and that the inclusion of responsibility utility in the model reduces the effect of the elicitation procedure to non-significance (z = 1.41, p = 0.158; see Model 2 of Table 3). In other words, responsibility utility fully explains the discrepancy across the agentic and non-agentic SWB measures.

3.2.5 Discussion

The results of the experiment illustrate one core message of this paper: people’s rank-orderings of outcomes can differ systematically depending on whether they are passive recipients versus whether they choose the outcome (see Prediction 4 in Sect. 2.1.4). Moreover, the discrepancy in rank-ordering across agentic and non-agentic procedures was fully accounted for by our survey measure of responsibility utility (in line with Prediction 3). Finally, the results are in line with our Prediction 5, that attributes which deliver responsibility utility (in this case, the higher amount others are paid) will be weighted more heavily in preference than in desirance.

The study has some limitations, however. First, respondents who we had assigned to a non-agentic condition reported feeling agency (see footnote 13). Second, anticipated SWB data might not exclude forms of expressive utility other than responsibility utility, e.g. social desirability bias. For example, subject A might report that she is made satisfied by participant B receiving a higher payment than subject A will herself receive but might secretly resent participant B’s good fortune. These two limitations suggest that accurately capturing a desirance is a difficult process and future work is needed to identify the best measures for desirances.

A third limitation concerns our analysis in Model 2. There was potential for an order effect in our study design. We asked the three questions on responsibility utility directly after the satisfaction questions, and, as a result, some subjects might have answered the “how good would you feel” questions to align with the ranking that they had expressed just a moment before. It is not possible to measure our key variables within a single survey such that we would eliminate the risk of some potential order effect.Footnote 15 However, any potential order effect could have no bearing on our primary dependent variable—the satisfaction rankings that the subjects made—because we elicited these rankings before presenting any other questions. The concern is that an order effect may have inflated the correlation between the satisfaction question and the virtue50—virtue35 measure. As a result, it is possible that our Model 2 result overstates the degree to which responsibility utility explains differences across the agentic and non-agentic satisfaction rankings.

3.3 Can marginal rates of substitution be inferred from happiness data? A reconsideration

A recent stream of research by Benjaminet al. (2012,2014,2020) compares the trade-offs implied by choice (marginal rates of substitution) with those implied by anticipated SWB. They find that SWB trade-offs differ from marginal rates of substitution, but do not propose a theory to explain this difference. To identify differences between SWB trade-offs and marginal rates of substitution, the 2012 paper presents a series of hypothetical alternative outcomes and asks “which do you think would give you a happier life as a whole?” and “which do you think you would choose?” (pp. 2087–8). The 2014 paper asks medical students to report SWB based on their anticipated experiences at their top-ranked residencies. The paper then compares these SWB ratings with the students’ incentive-compatible rankings of residencies and identifies differences across both measures. Benjamin et al. (2020) summarise these papers writing that the “findings from these two papers suggest that people care about more than just what is measured by standard, single-question survey measures of ‘happiness’ or even ‘life satisfaction’.” (2020, p. 4). As such, they argue, policy making should not yet rely on SWB data.

Our framework and the experiment presented in the previous section suggest that responsibility utility provides one potential explanation for the differences Benjamin and co-authors find between anticipated SWB trade-offs and marginal rates of substitution: It may be the case that for some participants in these studies responsibility utility was greater in choice than in anticipated SWB.

Whether responsibility utility informs choice more than it informs anticipated SWB is a question for future research. It will depend in part on whether the anticipated SWB questions are agentic or not. For example, we do not know whether participants in Benjamin et al. (2012) interpreted the anticipated SWB questions as non-agentic (along the lines of “which do you think would give you a happier life as a whole if it were to happen to you via some exogenous mechanism?”) or as agentic (along the lines of “which do you think would give you a happier life as a whole if you were to have chosen it?”). For a systematic difference to arise between choice and SWB, it would be sufficient that just a subset of participants interpreted the question as non-agentic. Even if most respondents interpreted the question such that responsibility utility was equal in choice and in SWB, when trade-offs are inferred from sample averages that majority would dilute but not neutralise the systematic discrepancies induced by respondents for whom responsibility utility was stronger in choice than in anticipated SWB.

Similarly, in Benjamin et al. (2014), it is not clear how responsible participants would have felt for ending up at the various residencies they were asked about in the SWB question. On the one hand, the survey highlighted to respondents their role in ending up at the residency by reminding them of the choice ranking they had previously submitted and through question wordings that referred to “your chosen residency”, “the programs you ranked”, and “the preference ordering you submitted” (our italics). On the other hand, when asked the SWB question “Thinking about how your life would be if you matriculate into the residency program in [residency you have just indicated you ranked in second position], please answer…” the student will have known that the only mechanism that could result in their ending up at their second-ranked residency is because the matching algorithm sent them there. In other words, students were entirely responsibility for the ranking of residencies that they submitted but may not have considered themselves entirely responsible for the scenarios over which they were estimating SWB. This mechanism could potentially explain why attributes that contribute toward responsibility utility (e.g., desirability for significant other) predicted trade-offs in ranking more strongly than trade-offs in anticipated SWB.

Where responsibility utility differs systematically across choice and anticipated SWB, SWB trade-offs should not be interpreted as marginal rates of substitution. However, our framework suggests SWB trade-offs might be equivalent to marginal rates of substitution when responsibility utility is identical across both procedures. For example, if participants interpreted anticipated SWB questions as agentic, i.e. to mean something like “which do you think would give you a happier life as a whole if you were to have chosen it?”, our framework would expect similar trade-offs compared to the question “which do you think you would choose?”. A second example concerns situations where responsibility utility is zero. This reasoning is in line with the result in Benjamin et al. (2012) showing that choice data and SWB data did not differ systematically when participants were presented with the alternatives of an apple and an orange—a choice that is very unlikely to deliver any responsibility utility. Future research should investigate the extent to which variations in responsibility account for discrepancies across choice and SWB. It remains possible that this research will show that current SWB measures can provide comprehensive welfare measures that correspond to MRSs.

We close by observing that there may exist other sources of discrepancy across choice and SWB and future research ought to examine how these relate to responsibility utility. For example, Benjamin et al. (2012) show that people are systematically more likely to choose options that provide more money than they are likely to indicate that this “money-option” will lead to higher SWB. Responsibility utility could explain this if people anticipate greater negative responsibility utility from missing out on money than from missing out on higher levels of well-being. Alternatively, people may choose the option with higher monetary payoffs more frequently than they anticipate higher SWB from it for reasons totally unrelated to responsibility utility, e.g., because tit-for-tat or lay rationalist rules inform decision making more readily than they inform SWB forecasts (e.g., Amir and Ariely 2007; Comerford and Ubel 2013; Hsee et al. 2003, 2015). With the existing data, we cannot distinguish between these various explanations. However, one of the contributions of the current paper is that we suggest simple survey questions to measure responsibility utility and so test whether it explains the observed results.

3.4 Implications for policy evaluation

The distinction between preferences and desirances has several implications for the way welfare economists evaluate policies. The first implication is that variation in responsibility utility must be considered when extrapolating from one choice situation to another. The literature review presented in Sect. 2.2 demonstrates that the preferences revealed by choice data are sensitive to features of the choice environment that alter responsibility utility. When extrapolating from one choice context to another, it is important to account for responsibility utility if choice predictions and welfare estimates are to be accurate. Relatedly, accounting for responsibility utility might expand the applicability of choice-based welfare measures. Choice-based welfare analysis grinds to halt when confronted with a preference reversal because the economist is confronted with contradictory preference orderings (Bernheim and Rangel 2009). Variations in responsibility utility offer a promising explanation for some preference reversals reported in the literature, as demonstrated by our examples in Sect. 2.2. The upshot is that a more coherent ordering in terms of expected utility is likely to be retrieved from revealed preferences if responsibility utility is accounted for.

A second implication of responsibility utility is that choice data may not always and everywhere be the gold standard measure of utility. When the aim is to measure welfare effects of outcomes imposed on a population of passive recipients,Footnote 16 choice data is expected to deliver utility measures that are biased to the extent that they are contaminated by responsibility utility. Hence, alternative measures to infer choiceless utility are needed in situations where responsibility utility should not be included in the welfare evaluation of a policy. We suggest experienced and anticipated SWB as promising candidates for such welfare evaluations and look forward to further work on this important topic.

Notes

The joke runs as follows: My grandmother was on a train with a stranger. They both ordered a slice of cake. When the cakes arrived, one slice was conspicuously larger than the other. My grandmother smiled and said that she would take the smaller slice. A few weeks later, she found herself in the identical situation: same passenger, same scenario with the cakes. This time, her fellow passenger immediately lunged forward and grabbed the larger cake. “How rude of you!”, my grandmother exclaimed. “Oh?” replied the passenger innocently, “and how would you have behaved?” “I would have offered you the larger slice, of course.” “And I would have taken it. You got exactly what you want.”.

We suggest using the term “desirance” because the notion of desire connotes that persons who desire lack the agency to bring about their desired outcomes. Also, the word “desirance” is novel and so unambiguous (unlike liking, which we also considered).

Where welfare analysis seeks to estimate the benefits delivered by having chosen a good, status-quo welfare analysis should perform well (if we ignore cognitive biases as discussed in Weimer 2017), because the appropriate measure is a preference ordering and the appropriate data is incentive-compatible choice. The debate on the validity of choice data in these circumstances is beyond the scope of the current discussion (see Bernheim 2016; Sunstein 2020; Weimer 2017).

Procedural utility predicts that choiceless utility might differ depending on whether an outcome is delivered by natural forces or by a dictator (Frey et al. 2004). This insight does not trouble our analysis, it simply means that an outcome delivered by natural forces should be modelled as a different outcome if delivered by a dictator. We do this all the time in life: a coat produced according to fair trade principles is valued as a substantively different good to an otherwise identical coat that is produced in a sweatshop.

To illustrate, one potential function of the responsibility utility that an individual derives from choosing good \(x\) could be \(r\left(x\right)=v\left(x\right)*res\left(x\right)\), where \(v(x)\) is the valence of choosing \(x\) and \(res(x)\) the extent of feeling responsible for \(x.\) This is how we model responsibility utility empirically in Sect. 3.2.

We can think of other functional forms of responsibility utility, such as concave utility functions. However, we stick to the most straightforward illustration here.

Pure altruists are often referred to as having pro-social preferences or other-regarding preferences. Our framework suggests that more accurate terms would be “pro-social desirances” or “other-regarding desirances” because a pure altruist, by definition, does not derive responsibility utility from the gain of others (Andreoni 1990; Crumpler and Grossman 2008).

Note that there are two variations simultaneously induced by the treatment in the study by Choshen-Hillel and Yaniv (2011), one is the procedure that respondents answer by and the second is whether the respondent is asked for a desirance or a preference.

Note that while the non-responsibility criterion makes sure that responsibility utility does not bias people’s rank orderings, the criterion is not sufficient to exclude the possibility of other forms of expressive utility informing the orderings. For example, it is possible that individuals gain expressive utility from the act of answering desirance questions by stating that they would rather outcome A than outcome B and thus sending a signal to themselves and to others.

Hypothetical bias refers to any systematic mismatch between the utility ordering a respondent manifests in response to a hypothetical question and the utility ordering the same respondent exhibits in an incentive-compatible choice situation (Hausman 2012). Hypothetical bias can arise for reasons of self-presentation (e.g., social desirability bias) or because, relative to a situation where the respondent has skin-in-the-game, there is simply less incentive to think through a hypothetical choice. An approach to overcoming hypothetical bias is to introduce incentive compatibility to elicitation procedures (e.g., Johansson-Stenman and Svedsäter 2012).

There were no differences in age and gender across the agentic and non-agentic conditions (both p-values > .7) and so we test our hypotheses using bivariate models.

We expected the mean responsibility score in the non-agentic condition to be close to zero, but in fact it was 2.22. Some respondents reported that they would feel “somewhat responsible” for an outcome that they had just been told would be determined by a random process. One explanation for this result is that some respondents engaged in “magical thinking” (Quick et al. 2016). A more prosaic explanation is response error. Either way, our manipulation was successful at engendering greater feelings of responsibility in the agentic condition than in the non-agentic condition.

While it might be expected that nothing other than agentic SWB would predict choice, we note that, independent of the explanatory effect of agentic SWB, choice was predicted by responsibility utility (n = 49, z = 2.25, p = 0.024). This result is driven by the three cases where choice deviated from agentic SWB. Though we do not attempt to interpret anything from a sample of three, one possible explanation consistent with this result is that the intervening questions on responsibility utility prompted respondents to consider which option would give greater responsibility utility and so caused them to choose that option.

Counterbalancing the order would not eliminate potential question order effects; the correlation between the responsibility utility questions and the ranking might still be inflated by presenting the questions one after the other, regardless of the order they are presented in. One way that might overcome these problems would be to elicit responsibility utility at one point in time and satisfaction rankings at another, allowing sufficient time between the two so that respondents forget their earlier responses. Still there would be no way to verify the absence of an order effect and the passage of time risks real and substantive changes which introduce noise and perhaps bias into the measures.

Of course, some policies are not imposed on a population but are, to some extent at least, selected by that population. The most obvious such case is a referendum, where each voter has agency over the policy outcome. An important question for future research is to what extent voters in democratic societies feel responsibility utility regarding government-imposed policies. We suspect that there are likely individual differences in these feelings of responsibility (e.g., locus of control) and that they are likely to be explained by self-serving biases (e.g. higher feelings of responsibility ex post if a policy turns out to have had positive versus negative consequences).

References

Aknin LB, Norton MI, Dunn EW (2009) From wealth to well-being? Money matters, but less than people think. J Posit Psychol 4:523–527

Aknin LB, Barrington-Leigh CP, Dunn EW, Helliwell JF, Burns J, Biswas-Diener R et al (2013) Prosocial spending and well-being: cross-cultural evidence for a psychological universal. J Pers Soc Psychol 104:635–652

Amir O, Ariely D (2007) Decisions by rules: the case of unwillingness to pay for beneficial delays. J Mark Res 44(1):142–152

Andreoni J (1990) Impure altruism and donations to public goods: a theory of warm-glow giving. Econ J 100:464–477

Arrow KJ (1950) A difficulty in the concept of social welfare. J Polit Econ 58:328–346

Atkinson G, Braathen NA, Mourato S, Groom B (2018) Cost benefits analysis and the environment: further developments and policy use. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris

Baerger DR, McAdams DP (1999) Life story coherence and its relation to psychological well-being. Narrat Inq 9(1):69–96

Benjamin DJ, Heffetz O, Kimball MS, Rees-Jones A (2012) What do you think would make you happier? What do you think you would choose? Am Econ Rev 102:2083–2110

Benjamin DJ, Heffetz O, Kimball MS, Rees-Jones A (2014) Can marginal rates of substitution be inferred from happiness data? Evidence from residency choices. Am Econ Rev 104:3498–3528

Benjamin D, Cooper K, Heffetz O, Kimball M (2020) Self-reported wellbeing indicators are a valuable complement to traditional economic indicators but are not yet ready to compete with them. Behav Public Policy 4:1–12

Berger EM (2010) The Chernobyl disaster, concern about the environment, and life satisfaction. Kyklos 63:1–8

Bernheim BD (2016) The good, the bad, and the ugly: a unified approach to behavioral welfare economics. J Benefit-Cost Anal 7:12–68

Bernheim BD, Rangel A (2009) Beyond revealed preference: choice-theoretic foundations for behavioral welfare economics. Q J Econ 124:51–104

Bobadilla-Suarez S, Sunstein CR, Sharot T (2017) The intrinsic value of choice: the propensity to under-delegate in the face of potential gains and losses. J Risk Uncertain 54(3):187–202

Bodner R, Prelec D (2003) Self-signaling and diagnostic utility in everyday decision making. The Psychology of Economic Decisions 1:105–126

Bullock JG, Gerber AS, Hill SJ, Huber GA (2015) Partisan bias in factual beliefs about politics. Quart J Political Sci 10:519–578

Chmielewski M, Kucker SC (2020) An MTurk crisis? Shifts in data quality and the impact on study results. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 11(4):464–473

Choshen-Hillel S, Yaniv I (2011) Agency and the construction of social preference: between inequality aversion and prosocial behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 101:1253

Comerford DA, Ubel PA (2013) Effort aversion: job choice and compensation decisions overweight effort. J Econ Behav Organ 92:152–162

Crumpler H, Grossman PJ (2008) An experimental test of warm glow giving. J Public Econ 92(5–6):1011–1021

DellaVigna S, List JA, Malmendier U (2012) Testing for altruism and social pressure in charitable giving. Q J Econ 127(1):1–56

Di Tella R, MacCulloch RJ, Oswald AJ (2001) Preferences over inflation and unemployment: evidence from surveys of happiness. Am Econ Rev 91:335–341

Dietvorst BJ, Simmons JP, Massey C (2015) Algorithm aversion: people erroneously avoid algorithms after seeing them err. J Exp Psychol Gen 144(1):114

Frey BS, Benz M, Stutzer A (2004) Introducing procedural utility: not only what, but also how matters. J Inst Theor Econ JITE 160:377–401

Gintis H (2009) The bounds of reason: game theory and the unification of the behavioral sciences. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Gul F, Pesendorfer W (2005) The revealed preference theory of changing tastes. Rev Econ Stud 72:429–448

Hamman JR, Loewenstein G, Weber RA (2010) Self-interest through delegation: an additional rationale for the principal-agent relationship. Am Econ Rev 100:1826–1846

Hausman DM (2010) Hedonism and welfare economics. Econ Philos 26:321–344

Hausman J (2012) Contingent valuation: from dubious to hopeless. J Econ Perspect 26:43–56

Hillman AL (2010) Expressive behavior in economics and politics. Eur J Polit Econ 26:403–418

Hsee CK, Zhang J, Yu F, Xi Y (2003) Lay rationalism and inconsistency between predicted experience and decision. J Behav Decis Mak 16(4):257–272

Hsee CK, Yang Y, Zheng X, Wang H (2015) Lay rationalism: individual differences in using reason versus feelings to guide decisions. J Mark Res 52(1):134–146

Johansson-Stenman O, Svedsäter H (2012) Self-image and valuation of moral goods: stated versus actual willingness to pay. J Econ Behav Organ 84(3):879–891

Kahneman D, Wakker P, Sarin R (1997) Back to Bentham? Explorations of experienced utility. Quart J Econ 112(2):375–405

Loomes G, Sugden R (1982) Regret theory: an alternative theory of rational choice under uncertainty. Econ J 92:805–824

Luttmer EFP (2005) Neighbors as negatives: relative earnings and well-being. Q J Econ 120:963–1002

Morton RB, Ou K, Qin X (2019) Reducing the detrimental effect of identity voting: an experiment on intergroup coordination in China. J Econ Behav Organ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2019.02.004

Oppenheimer DM, Meyvis T, Davidenko N (2009) Instructional manipulation checks: detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. J Exp Soc Psychol 45(4):867–872

Pareto V (1971) Manual of political economy. Macmillan, New York

Quick BL, Reynolds-Tylus T, Fico AE, Feeley TH (2016) An investigation into mature adults’ attitudinal reluctance to register as organ donors. Clin Transplant 30(10):1250–1257

Robbett A, Matthews PH (2018) Partisan bias and expressive voting. J Public Econ 157:107–120

Sah S, Loewenstein G, Cain DM (2013) The Burden of disclosure: increased compliance with distrusted advice. J Pers Soc Psychol 104:289–304

Samek A, Sheremeta RM (2017) Selective recognition: how to recognize donors to increase charitable giving. Econ Inq 55:1489–1496

Samuelson PA (1954) The pure theory of public expenditure. Rev Econ Stat 36:387–389

Schuessler AA (2000) Expressive voting. Ration Soc 12:87–119

Spenkuch JL (2018) Expressive vs. strategic voters: an empirical assessment. J Public Econ 165:73–81

Steptoe A, Deaton A, Stone AA (2015) Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet 385(9968):640–648

Sunstein CR (2007) Willingness to pay vs. welfare. Harv. L. & Pol’y Rev. 1:303

Sunstein CR (2020) Behavioral welfare economics. J Benefit-Cost Anal 11:1–21

van de Ven N, Zeelenberg M (2011) Regret aversion and the reluctance to exchange lottery tickets. J Econ Psychol 32:194–200

von Neumann J, Morgenstern O (2007) Theory of games and economic behavior. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Weimer DL (2017) Behavioral economics for cost-benefit analysis: benefit validity when sovereign consumers seem to make mistakes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to members of the Stirling Behavioural Science Centre and the UCD Behavioural Science and Policy Group, participants at the NIBS conference 2016, the Munich Micro Workshop, the LSE Wellbeing Seminar Series, and especially to Ori Heffetz for excellent comments on earlier versions on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Comerford, D.A., Lades, L.K. Responsibility utility and the difference between preference and desirance: implications for welfare evaluation. Soc Choice Welf 58, 201–224 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-021-01352-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-021-01352-9