Abstract

We elicit distributional fairness ideals of impartial spectators using an incentivized experiment in a large and heterogeneous sample of the German population. We document several empirical facts: (i) egalitarianism is more popular than efficiency- and maxi-min ideals; (ii) females are more egalitarian than men; (iii) men are relatively more efficiency minded; (iv) left-leaning voters are more likely to be egalitarians, whereas right-leaning voters are more likely to be efficiency-minded; and (v) young and high-educated participants hold different fairness ideals than the rest of the population. Moreover, we show that fairness ideals predict preferences for redistribution and intervention by the government, as well as actual charitable giving, even after controlling for a range of covariates. This paper thus contributes to our understanding of the underpinnings of voting behavior and ideological preferences and to the literature that links laboratory measures and field behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

How should we divide the pie? Despite the apparent simplicity of this question, the division of scarce resources is one of the most fundamental problems we face. In any distributional question, scarcity of means and plurality of goals collide, while material self-interest and social concerns might conflict. Recent empirical evidence shows that individuals tend to disagree on how the trade-off between personal income and fairness considerations is best resolved and on what the fairest outcome is. It is often assumed that left-wing voters are relatively egalitarian, while the political right is thought to focus more on efficiency. A disagreement about which qualities make a distribution or outcome desirable can greatly complicate any discussion that impacts the final distribution. If the difference of opinion between the political left and right is driven by fundamentally different views on what is fair, it is not surprising that political debate on issues like redistribution, the welfare system, or the provision of universal health care becomes heated. Finding an acceptable middle ground will require all parties to make concessions with regard to their moral ideals. Knowledge about these ideals can therefore greatly benefit the search for acceptable policies and achievable reform.

In this paper, we measure the prevalence of four stylized distributional fairness types and relate them to personal characteristics and political preferences (an additional result in the appendix also relates fairness preference to charitable giving). To do so, we run an incentivized experiment in a large and heterogeneous sample (N = 2890 completed responses) of the German population in the German Internet Panel (GIP). In two tasks, the decision maker selects an allocation of money for two other, anonymous persons. By paying other respondents the chosen amounts, we incentivize decision makers to think about which distribution they consider fair.Footnote 1 We consider four normative criteria (types) suggested in the literature: equality of outcomes (egalitarian), maximizing the minimum (maxi-min), maximizing the total amount of resources (efficiency), and maximizing the highest outcome (maxi-max). The allocations are constructed in such a way that each of the criteria leads to a different choice by a decision maker.

Spectator-type moral ideals are of significant importance in the organization of societies. In many political or policy decisions, an individual’s self-interest is not, or only indirectly, involved. Voters are asked to decide on many policy proposals that may never directly affect them, from the availability of birth control to women (for male voters), to a change in tax rates for incomes above their own, to the placement of a large power plant far away from their homes. Still, males, US conservatives, unions, and environmental organizations, respectively, have put up very strong campaigns around these proposals. Clearly these policies matter to voters, even if they are not personally affected by them. In the economic sphere, a spectator’s view plays a vital part when a company or person declares bankruptcy. A impartial third party is brought in to determine a fair way of distributing the (insufficient) assets over the competing claims. Despite the importance of spectator’s judgments, existing empirical evidence focuses mostly on situations where the decision maker has a personal monetary stake in the outcome and thus faces a potential trade-off between morals and self-interest. In this paper we avoid this trade-off completely and focus on spectator ideals directly.

If individuals want to express their fairness ideals at a societal level, they can do so by voting for parties or policies that bring outcomes closer to those ideals. The political sphere is a good test case for the abstract, spectator-type fairness ideals, as the link between individual votes and societal outcomes is weak. If fairness ideals shape voting behavior, one would expect that individuals with egalitarian fairness ideals are more likely to support redistributive policies as these reduce inequality. Since these interventions tend to come at a cost, one would expect individuals who put more weight on efficiency are less likely to support such policies. A preference for more (less) redistribution should also increase the tendency of individuals to vote for more left-wing (right-wing) parties since left-wing parties tend to focus more on equality over efficiency than right-wing parties, ceteris paribus. Hence, we also expect these preferences to influence voter behavior after controlling for other relevant factors.

Our main findings are that fairness preferences significantly relate to (i) support for government interventions to reduce inequality and (ii) views on tax rates, (iii) voting behavior. Secondary results, presented in the Appendix, show that egalitarian types are also more likely to donate money to charity than all other types. All these results continue to hold after including a battery of controls. Furthermore, we document several empirical facts regarding the distribution of fairness ideals. First, our sample of the German population predominantly and consistently chooses egalitarian allocations. From an economic point of view, these choices are striking: in both choice tasks the egalitarian option is (weakly) Pareto-dominated by at least one other allocation. Second, females are more egalitarian than males across all age groups. Third, males are more efficiency-minded than females. These two results are similar to a recurring finding in the literature on self-involved fairness that females put more weight on other people’s income.Footnote 2 Fourth, left-leaning voters are more likely to be egalitarian, whereas right-leaning voters are relatively more likely to be efficiency-minded. A noteworthy deviation from this trend can be found at the very extremes of the distribution. Individuals who place themselves at the extreme left or extreme right end of the political spectrum are overwhelmingly egalitarian. Fifth, age, education, and earnings all significantly correlate with fairness ideals. Since these are exactly the characteristics which differentiate students from the general public, our study also contributes to the question whether the fairness ideals held by students are similar to those found in the rest of the population as is discussed in Cappelen et al. (2007), Bellemare et al. (2008), Gaertner and Schokkaert (2011), Cappelen et al. (2015) and Fisman et al. (2017) for example. However, many of these studies have been confined to hypothetical settings (Konow 2003), our incentivized spectator design provides complementary results. Finally, maxi-max preferences are empirically irrelevant. Given that randomly clicking individuals would have chosen this option in 25% of the cases, we take this as evidence that individuals make deliberate choices.

We proceed as follows. In Sect. 2 we briefly discuss existing theoretical and empirical fairness research. Section 3 describes the survey and the experiment. Section 4 depicts the distribution and correlates of fairness views in our sample of the German population. Section 5 shows that fairness measures have predictive power for preferences about government intervention to reduce inequality, the tax rates and voting behavior. Section 6 concludes the article. The results regarding the correlation of fairness preferences and revealed charitable giving can be found in the Appendix.

2 Views on distributive justice

Social scientists have shown a great interest in fairness preferences, most commonly in situations in which the decision maker has a stake in the distribution and has no uncertainty about her own position. In the laboratory, this situation is mimicked by the classical dictator game (Kahneman et al. 1986), in which a decision maker decides on how to split a pie between herself and one other person. This game has had a large impact through the insight that people often care about the income of others. These findings led to the development of social preference models (Fehr and Schmidt 1999; Bolton and Ockenfels 2000) that not only emphasize the perceived (distributional) fairness of outcomes.Footnote 3

Besides the recent interest in perceived fairness of outcomes, there is a long tradition of studying impartial fairness from a normative point of view in philosophy, economics, and political science. In this tradition, researchers are interested in how a decision maker should choose between different income distributions. In their seminal works, Harsanyi (1953) and Rawls (1971) famously propose that the decision maker needs to be behind the veil of ignorance to achieve a just decision. That is, to make a fair decision, the decision maker should be ignorant of her own income, social status, wealth, abilities etc., and thus ignorant of her own stake in the outcome. In this original position, decision makers are then able to make judgments about income distributions which are free of self-interest. Hence, the veil of ignorance can be seen as a thought experiment aimed at reaching impartiality of decision makers, which should lead to fair and just outcomes.

There are many ways to define and measure fairness ideals. We focus on an abstract spectator setting that is both easy to implement and context free. This provides a complementary approach to the more specific instruments that measure preferences given certain contextual factors like production or risk (e.g. Konow 2000; Cappelen et al. 2013; Almås et al. 2019). All of these experiments involving fairness likely capture related behavioral traits. Through the abstract nature of the elicitation, we try to elicit preferences that transfer to different contexts more easily and are thus a stable aspect of preferences. The significant correlations found with policy preferences, political preferences, and charitable donations seem to indicate that they are indeed stable and travel across contexts.

2.1 Empirical literature

The empirical literature on fairness is split into several methodologies, with some studies using a set-up inspired by the veil of ignorance and others using spectator judgments. Most empirical papers based on the veil of ignorance are versions of dictator games with uncertainty about the decision maker’s position in the final allocation (e.g. Bosmans and Schokkaert 2004; Schildberg-Hörisch 2010). In contrast, the majority of empirical papers that focus on spectator judgments are so-called vignette studies. These studies present hypothetical situations to participants, who are then asked to make a choice or judgment. The choice made reveals some aspect of participants’ values or social norms applicable to the situation.Footnote 4 The incentivized impartial spectator we use in our experiments, was used by Konow (2000) to test the accountability principle as a basis of perceived fairness and by Cappelen et al. (2013) to study the impact of luck and risk on fairness preferences in spectators and in stakeholders and spectators, respectively.

Traub et al. (2005) highlight the importance of the distinction between spectator and veil of ignorance judgments, as well as the importance of the amount of information possessed by their subjects when making a moral judgment. They find a statistically significant difference between the choices made by subjects when they switch from a self-concern (veil of ignorance) to an umpire mode (impartial observer). In their experiments, subjects are asked to judge lotteries. Those who are informed about the associated probabilities of the lotteries are more inequality averse as umpires than as decision makers behind the veil. Subjects who do not know the associated probabilities are less inequality averse as umpires than as involved decision makers behind the veil. Similarly, Croson and Konow (2009) compare behavior behind the veil of ignorance with impartial spectators and find that “stakeholders are less inclined to respond to the generosity of others than are spectators”. More recently, Becchetti et al. (2011) show that impartial spectators and, to a smaller extent, stakeholders behind-the-veil both reward talent more strongly than informed stakeholders.

Konow (2009) presents interesting results regarding the choices of impartial spectators. His vignette study shows that spectators are more likely to agree on what is fair when they possess more information. This finding suggests that the impartial spectator is an attractive approach to elicit fairness preferences. One might hope to find agreement when all relevant information is known. Amiel et al. (2009), using a vignette survey with students in several countries, present evidence suggesting that impartial spectators behavior is impacted more by social concerns (i.e. they transfer more money) than involved participants. Aguiar et al. (2013) compare fairness views of planners behind the veil of ignorance, impartial spectators and ideal observers (who are assumed to be omniscient) to find out which of those procedures is most useful in ensuring impartiality. They find that the ideal observers choose significantly more equal distributions than stakeholders behind the veil or impartial spectators. A benevolent dictator (a third party observer) is also used in Cettolin and Riedl (2016) as a device to elicit fairness ideals under conditions of uncertainty. Their result indicates that the fairness of uncertain allocations, like their certain counterparts, is judged according to a variety of different ideals.

In a study related to ours, Almås et al. (2019) compare the fairness preferences of Scandinavians and Americans using a large-scale online experiment. They show that Americans and Scandinavians differ significantly in their fairness views. While they also use a spectator design, there are several differences to our study. Specifically, Almås et al. (2019) (i) employ a different experimental design, including different treatments and different roles (‘workers’ versus ‘spectators’); (ii) introduce luck and merit; (iii) use American and Scandinavian participants, not German ones; (iv) have a significantly smaller set of socio-demographic background information; (v) and do not correlate behavior in the experiment with redistributive preferences and charitable giving. Differences (i) and (ii) have a strong impact on the design, as they result in a different set of fairness types.

In this paper, we document fairness types in a large, heterogeneous sample of the German population. Such samples exhibit a larger variation in demographic characteristics than standard lab samples, allowing for a more accurate picture of preferences in the population. In addition, the panel vehicle offers rich information about subjects collected in many waves over several years. Consequently, we can correlate fairness ideals to a large range of demographic variables as well as to political and policy preferences, and charitable behavior. Moreover, we show that our parsimonious and abstract approach to classify respondents into fairness types captures important aspects of individual preferences, that help to predict and understand voting behavior beyond what is contained in demographic variables.

2.2 Normative fairness ideals

Normative theory has carved out several ideal types of distributive justice. In our empirical analysis, we exploit the fact that these different normative theories predict different choice patterns and assign a fairness type to our participants based on the criterion that is revealed to be most important to the decision maker. This paper focuses on four types, egalitarian, maxi-min, efficiency, and maxi-max.

First, egalitarianism proposes a simple comparison rule for allocations (e.g., Roemer 1996). In this philosophy, equality is considered the only moral or fair criterion by which to judge outcomes. Hence, in this view, differences in outcomes (e.g., income) should be minimized. Although there is some discussion about what should be equalized, egalitarians are expected to redistribute windfall gains, such as any earnings from the experiment, equally. In our experiment, egalitarianism violates the Pareto principle, as the egalitarian allocation is dominated by the maxi-min allocation. Intriguingly, we find that egalitarianism is the most popular ideal type.

Second, Rawls (1971) suggested that if people were to be placed behind the veil of ignorance, they would choose distributions according to the difference principle. This principle selects the distribution that maximizes the minimum income. Based on the assumed general acceptance and impartiality of the participant behind the veil, he argues that this maxi-min rule is the only moral or fair selection criterion. However, from an empirical point of view, support for this principle seems somewhat less compelling. Frohlich and Oppenheimer (1990) find little support for the maxi-min principle, instead many participants endorse the efficiency principle with a floor constraint, i.e. maximize the sum as long as a minimum income is guaranteed.Footnote 5 In contrast, Mitchell et al. (1993) find considerable support for Rawls’ maxi-min principle in an experiment with a hypothetical society and decision makers behind the veil of ignorance. Similarly, Michelbach et al. (2003) find that a “considerable minority” uses maxi-min as a decision criterion.

Third, the (weak) Pareto principle allows another simple approach to distributive justice. If in allocation \(\mathcal {A}\) at least one person is better off and no one is worse off than in allocation \(\mathcal {A}'\), then \(\mathcal {A}\) Pareto-dominates \(\mathcal {A}'\) and \(\mathcal {A}\) should be preferred to \(\mathcal {A}'\). While this principle is compelling, it does not provide a complete ranking of all potential allocations, i.e. it does not compare losses of one individual with the gains of another. If these losses and gains are treated equally, this boils down to the simple efficiency ranking as, for example, proposed by Posner (1983). In the monetary allocations in our experiments, efficiency yields the same ranking of distributions as Harsanyi’s Harsanyi (1953), Harsanyi (1955) utilitarianism, as long as one assumes that utility is (close to) linear in the sums of money involved. Hence, to the extent that utility functions are linear over the stakes in our experiment, utilitarianism does not require separate attention in our set-up. Efficiency concerns have been shown to play an important role in settings with personal stakes in the distribution of money (Charness and Rabin 2002; Engelmann and Strobel 2004), but less is known in situations involving impartial spectators.

Finally, one can also obtain a (partial) ranking of allocations based on the maximization of the highest income. Admittedly, this maxi-max criterion seems like a rather theoretical possibility. The position of the most advantaged individual does receive some attention in liberal thought in the Rawlsian tradition, but then mostly as something that might be envied (Green 2013). The maxi-max criterion gives a complete and transitive ranking of the alternatives (Brafman and Tennenholtz 1997). We included this criterion to test the reliability of our data. If it had been chosen by a similar number of participants as the other criteria, this could have been a signal of random choices. As it turns out, maxi-max preferences are empirically irrelevant (\(n=14\)). We will therefore not discuss any empirical results relating to maxi-max preferences. For completeness, we will however display them in the figures and tables.

3 Data

3.1 The German internet panel

Our experiment was part of wave 20 (November 2015) of the German Internet Panel (GIP). The GIP is maintained by the collaborative research center 884 “Political Economy of Reforms” at the University of Mannheim. The GIP is an well-established panel based on a probability-based sample of the German population between the ages of 16 and 75. Participants are recruited offline using face-to-face interviews, which precludes many of the potential data and subject issues common to online platforms. During recruitment, special care was taken to include people who generally do not have access to the internet (for example, by handing out tablets and computers).Footnote 6 A new wave is fielded every second month and all enrolled participants are invited to take part. Each wave consists of a series of questions from different research groups and takes around 20 min to answer, so that questions have to be relatively short.

The repeated nature of the survey is a big advantage for our research. It allows us to relate our experimental measures to demographic information and information about political and policy preferences collected in other GIP waves.Footnote 7 In terms of topics, the GIP predominantly covers attitudes towards reform policies, the (welfare) state, and general political opinions. The data from this survey are available for scientific use via the data archive of the GESIS Institute for Social Science. Participants are paid a flat fee for their participation in a wave, and additional payments are made if a participant completes all waves in a year. To this end, all participants hold an account with the GIP. Data about these payments are not usually available for research, but researchers connected to the collaborative research center can access them through a secure data facility. We use this data in the Appendix when we discuss charitable giving by our respondents.

3.2 The experiment

The standard approach in empirical justice research is the vignette study. Respondents are confronted with a hypothetical situation and given the relevant context and then they are asked to provide their judgment or choice. Vignettes have proven to be a useful instrument in empirical justice research. However, we believe that following the standard methodology of experimental economics has distinct advantages in our setting. First, it is unclear how to relate answers in vignette studies to the political variables and socio-demographic characteristics that we are interested in, without explicitly asking about similar problems. By using an abstract frame and avoiding loaded words like ‘fairness’ or ‘distribution’, we avoid the usual connotations associated with such words. This approach allows us to identify underlying preferences without an associated context. This should make it more likely that these preferences translate to other contexts, i.e. we try to capture a stable part of individual preferences. Second, a common problem in online surveys like the GIP is that many survey participants might not be willing to read lengthy texts describing the moral scenario to be evaluated in a vignette. Our design allows us to be brief and work without extensive explanations and can therefore avoid this issue. Monetary incentives are the paradigm in experimental economics, mainly to induce subjects to think carefully about their choices and to minimize concerns about experimenter-demand effects and hypothetical and social-desirability biases. As such, we consider them a vital part of our experiment.

The experimental task consists of two multiple-choice questions. Each question asks respondents to indicate their preferred allocation from four options. Each allocation specifies a distribution of money over two other, unknown, and randomly selected participants of the same experiment. The sum of the payments in each allocation is also shown to decrease cognitive burden on participants. The order of the options in every decision task is randomized across participants. This information is given to the respondents at the beginning of the experiment. No further information about the receivers of the money is given. As all respondents are recruited face-to-face from the German population, they should be aware that recipients are randomly selected from the German population.

The allocations are designed such that each fairness ideal makes a different prediction about which allocation should be chosen.Footnote 8 We use the two choices also to check consistency. The differences between the two choices create different trade offs, so that subjects might switch between options if the fairness criterion is not very important to them, or when they select randomly. The observed choices of our respondents are quite consistent in the primary fairness ideal over the two choices, which we take as an indication that subjects considered the choices and that they tended to select according to the identified fairness ideal in similar questions. Table 1 shows the options in the two tasks.Footnote 9

Table 1 lists the allocations participants could choose from for both choices. The average monetary value of each choice was around 20 Euro ($22 at the time the survey was fielded), which is more than twice the German federal minimum hourly wage. Winners were selected via the participant ID which identifies the responses of each participant over the GIP waves. This ID cannot be used to obtain any personal information, such as name and address of the person concerned. The selected subjects were informed about their winnings via e-mail, and payments were made via their account at the GIP. This procedure ensured anonymity. All of this was explained in the experimental instructions, so subjects were aware of this set-up before making their choices.

When explaining the incentives, we avoided the word “probability”. Instead, we explained that we would pay 400 randomly selected participants according to 200 randomly-selected decisions. Participants were not eligible to be selected more than once for payment. We also informed participants that about 3500 respondents were expected to participate in the GIP wave. We believe that this approach made it easier for subjects to understand the relevant probabilities. In general, the experiment was short and easy to understand, which we consider a distinctive advantage of the impartial spectator design and the neutral frame.

All in all, 3159 participants took part in the wave 20 of the GIP. Of those, 2890 participants completed our experiment. The GIP records the time it takes participants to complete the survey. We excluded all participants who spent less than 30 s on our experiment, leaving us with 2675 participants. Our conclusions remained virtually identical when we include all respondents. Moreover, and more importantly, we exclude 486 participants who were not consistent across the two questions. In the main part, we consequently use the 2189 participants who chose in accordance with the same stylized fairness type in both decision tasks.Footnote 10 We take the high degree of consistency as a good indication that choices were not made randomly. In the Appendix, we show that using only the first or the second choice to classify subjects does not change our results.

4 The distribution of fairness ideals in the German population

Figure 1 shows the distribution of consistent fairness types in our sample of the German population, in total and by gender. The most popular option, with roughly half of the choices, is egalitarianism while maxi-min and efficiency are chosen by the other half of the participants. This pattern is striking, since the egalitarian option was dominated by the maxi-min allocations. In economic terms, this finding implies that half of the participants in our sample demonstrate a willingness to reduce incomes to achieve more equality. Two other findings catch the eye in Fig. 1. First, females are clearly more likely to prefer the egalitarian allocation, and second, males are more likely to prefer the efficient allocation, although egalitarians are also the predominant types among males (\(\chi ^2\) on independence of the distribution: \(p<0.001\)).

Figure 2 depicts the fairness ideals by education: students and three groups of non-students. We split the sample of non-students according to the level of general education attained: those with no vocational training (low); those with some vocational training(mid); and those who passed the admission requirements for college (high). The figure shows that students are different from the rest of the population. A \(\chi ^2\) goodness-of-fit test rejects the null hypothesis of similarity of the distribution of students and non-students at all normal confidence levels (\(\chi ^2\), \(p<0.001\)). Even compared to the highly-educated non-students, students are less likely to choose the Pareto dominated egalitarian allocations. At the same time, both students and highly-educated non-students are about two times more likely to select the efficiency-maximizing allocation than the low-educated respondents. These findings hold important implications for empirical justice research which builds on laboratory/classroom experiments, as it shows that the prevalence of maxi-min types and efficiency types might be systematically overestimated in such studies.

A similar picture emerges in Fig. 3, which shows fairness ideals by age groups. In particular, in the 16 to 34 age group, maxi-min is the modal choice. Whereas in all other age groups, egalitarians are the most numerous (\(\chi ^2\), \(p<0.001\)). The fraction of efficiency-minded people somewhat decreases with age.

Figure 4a shows fairness ideals by net monthly income. We merged the income brackets with the lowest and highest 10% of the distribution to avoid cells with small numbers of observations. While we do not find any sudden shifts in the distribution between income levels, there are some visible trends. The distribution becomes less ‘downward sloping’ as income increases (\(\chi ^2\), \(p<0.001\)). This shift is mostly caused by the decrease in the fraction of egalitarians and the increase in the fraction of efficiency-minded people in the higher income brackets. In particular, the top ten percent are almost as likely to choose the maxi-min allocation as they are to choose the egalitarian allocation. They are almost four times more likely to choose the efficient allocation than the bottom ten percent.

Figure 4b shows fairness ideals by employment status. As before, we conclude that students (at school and at university) are the exception, rather than the rule. They are the only group where maxi-min as opposed to egalitarian types are modal and they are relatively more likely to choose according to the efficiency criterion. Another group that visibly stands out comprises participants who are not currently employed (either unemployed or homemakers). Here, egalitarians and maxi-min types are approximately balanced. It appears that employment status is a relatively strong predictor of these preferences (\(\chi ^2\), \(p<0.001\)).

4.1 Regression analysis

To assess the relative importance of these factors, we try to predict the observed fairness types. We standardize all explanatory variables. Table 2 reports the results.

The regressions mostly confirm our earlier conclusions. We find that gender and education are the strongest predictors of fairness types. Males are much more likely to be efficiency-minded and less likely to be egalitarian. A higher education mostly seems to shift individuals away from egalitarian preferences. Increases in age are related to an increase in the fraction of egalitarians and a decrease in the efficiency-seeking type. Although the student population clearly holds different fairness ideals than the rest of the population, this effect does not survive when we control for more covariates simultaneously. This result is an indication that students are not different per se, but that the difference between the student population and the non-student population is driven by age and education. Income is significant only in predicting maxi-min and efficiency-minded types (columns 1 and 3), respectively. The last variable, “East” is an extra control to account for the part of Germany in which the participant lives. It is the standardized version of a dummy equal to 1 if the participant lives in former East Germany.Footnote 11 As can be seen from Table 2, this control does not appear to be a significant predictor of fairness preferences.

5 Fairness views: relation to political and policy preferences

We now turn to our main research question—whether fairness ideals relate to policy preferences. Specifically, we look at three domains in which preferences and decisions are likely to be influenced by fairness ideals. First, many governmental policies influence the distribution of income. We therefore expect distributional preferences to influence preferences about policies, in particular for policy areas that directly deal with income (re-)distribution. Second, if individuals want to express their fairness ideals at a societal level in a democracy, they can do so by voting for parties with a policy platform that delivers the distribution closest to their optimal policy.

Since egalitarianism is defined by a dislike of inequality in our experiment. We hypothesize that voters who adhere to these ideals in the experiment, also display a greater aversion towards inequality in real life. In order to counter economic inequality in society, they can vote for parties or policies that promise to reduce inequalities. This implies that egalitarians should be more likely to support redistributive policies and higher taxation and also tend to vote for more left-wing parties (since these parties tend to focus more on equality over efficiency in general) ceteris paribus. Preferences for efficiency are characterized by a lower weight on equality and a stronger focus on efficiency. We hypothesize that individuals with such preferences are more likely to vote for parties that stress efficiency over equality (traditionally more right-wing parties) and are more likely to support policies that lead to more efficiency, such as lower taxes as taxes typically come with a deadweight loss.

5.1 Preferences for redistribution

To find relevant measures of policy preferences in the GIP, we first searched for questions that were repeated verbatim, related to redistribution or taxes, and had more than 1000 respondents in common with our experiment. This way, we uniquely identified our first policy question in three different waves. Then, we searched for questions about the tax system, again using the restriction that the question needed to have more than 1000 respondents in common with our experiment. We found one question that satisfied this restriction. The translated questions are (i) “Please rate to what extent you agree with the following statement: The government should take measures to reduce income inequality” (see Table 3, columns 1–3) and (ii) “Should people who earn more because they work more, be taxed more?” (column 4). Unlike the other survey items, this question brings considerations of effort. If the abstractly identified fairness ideals of our experiment are predictive in different contexts, they should still predict some of the preferences even when other aspects are also relevant. In this specific question, if our respondents would be willing to accept any inequality that can be attributed to differences in effort, we should find no relation between types and choices here. The fact that we do find significant correlations, gives us confidence that our abstract elicitation at least partially corresponds to more context (tax) related distributive preferences. These questions were asked in wave 15 (fielded January 2015), wave 17 (fielded May 2015) and wave 21 (fielded in January 2016).Footnote 12 In both questions, participants were asked to indicate their opinion on a 5-point Likert scale that runs from least willing to accept taxes and interventions (coded as 0), to most willing to accept taxes and interventions (coded as Table 4).Footnote 13

In all regressions in Table 3, the egalitarian types are the reference group. The coefficients on the other three types consequently display the average difference in policy preference of individuals between that type and the egalitarian type. In columns (1) and (3), the question was embedded in a survey experiment. The order of the questions in waves 15 and 21 was randomized over two groups of participants. We control for potential differences by including a treatment dummy (untabulated) in both cases. The dummy does not influence our results.

Table 3 shows that experimental fairness preferences are predictive of policy preferences, even after controlling for the standard battery of individual characteristics.Footnote 14 In all cases, the coefficients of the non-egalitarian types have the expected sign. In line with expectations, efficiency-minded people are consistently less likely to favor government intervention. Looking at the first three columns, it is particularly reassuring to find that the predictive power is robust over time. Even though wave 15 and 21 are a year apart, the relationship between our measures and participants’ opinions on government redistribution seems robust. It is remarkable, however, that we never find a significant difference between the maxi-min types and the egalitarians in these policy preferences.

Looking at the control variables, we find some interesting results. First, the positive coefficient on the male dummy is remarkable. Men seem to favor more redistribution and more tax intervention by the government than women, once fairness preferences are controlled for. Hence, our data indicates that the finding that females are more supportive of redistributive measures than males is driven by the differences in fairness ideals held by males and females. The male dummy loses significance in column (4), such that the generalizability of this finding remains an open question. The coefficient on the ‘Trust in government’ variable, measuring the trust an individual has in the federal government, is also surprising. The negative sign in the first three regressions indicates that individuals who trust the government more, want the government to intervene less. A study by Kuziemko et al. (2015) in the US finds the opposite effect. Although the effect is not very strong, we find it in all waves, even though these are up to a year apart. This result could be specific to the German setting. In Germany, trust in the government is relatively high, governmental redistribution has been a consistent part of the tax system, and after-tax inequality is relatively low. The feeling that the current system works well could result in both trust in the government and no desire for more intervention to reduce inequality. If this is the case, the result could easily reverse for countries like the US with less redistribution or less trust in the government. The coefficient on income has a negative and significant sign. Higher-income individuals are less likely to support higher redistribution, which is in line with material self-interest. Moreover, younger respondents are less likely to favor some form of redistribution, and this effect survives when we control for other covariates. The effect of education on policy preferences is less consistent. Higher-educated individuals have a slight preference for more redistribution and are more likely to favor high taxes on very high incomes, but the effect is not always significant. This effect survives in other specifications of the model. A final result is that participants living in former East Germany are more positive towards government interventions aimed at redistribution. This is not surprising given the history of this part of Germany, which greatly benefited from government investment after the fall of the Berlin wall.Footnote 15 The evidence in this section shows that experimental fairness measures help to predict preferences for government intervention and redistribution, even after controlling for the standard battery of demographic covariates.

5.2 Ideology and fairness types

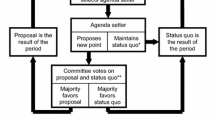

In this section, we study the relation of ideology, voting behavior and fairness ideals. The participants of the GIP are regularly asked to place themselves on the standard political scale from 1, ‘left’, to 11, ‘right’. We group participants into five groups and plot the relative frequency of fairness types for each group (see Fig. 5a), the answer-scales are shown in brackets. For the three largest groups of respondents in the center of the scale, we find that right-leaning participants are more likely to be efficiency-minded, while left-leaning participants are more egalitarian. Intriguingly, this relationship breaks down at the extremes of the scale. At both ends we find strong egalitarian preferences.Footnote 16

Next, we turn to the relation of voting behavior, and distributional fairness ideals. The GIP regularly asks participants what party they voted for in the last election and what party they identify with most. We split the sample of participants into groups based on the party they voted for in the last election.Footnote 17 The parties in Fig. 5b are grouped based on whether they are leftist (Die Linke, Bündis 90 - Die Grünen), centrist (SPD, CDU/CSU, FDP) or rightist (AfD, NPD). Figure 5b plots the differences relative to the overall distribution of fairness preferences. We calculate the distribution of fairness types within the sub-groups and subtract the average fractions found in the entire sample. The number between brackets indicates the number of participants that indicated to have voted for the party. In this figure, it becomes clear that left-leaning voters are more likely to be egalitarians and less likely to be efficiency-minded than right-leaning voters (\(\chi ^2\), \(p<0.001\)). The trend changes at the far-right (NPD). The term “National Socialism” seems to have been well chosen. In terms of their distributive fairness ideals, the far-right is closer the far-left than to the center. These political extremes likely define their in-group differently.Footnote 18 There is only limited empirical evidence concerning this presumed regularity in large, heterogeneous samples. Another interesting finding is the similarity between the established parties. The voter-base of each of the largest three parties is extremely close to the others and to the average German voter, which appears in line with the median voter theorem from Hotelling-Downs political competition models.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we make several contributions to the literature. First, we elicit the distribution of impartial-spectator fairness ideals of a large and heterogeneous sample of the German population using an incentivized and neutrally-framed experiment. While distributional preferences of stakeholders have often been studied, little is known about the fairness views of spectators in a broader population. These fairness views are important, as many real-life situations, particularly in the political arena, are closely approximated by an impartial observer. Surprisingly, our results show that egalitarians form the majority of the German population. This finding is unexpected, since egalitarian allocations are (weakly) Pareto-dominated in our experimental task.

Second, we contribute to the empirical literature that shows the plurality of fairness ideals held by individuals. We document a considerable individual heterogeneity of fairness ideals and we also show how individual characteristics are correlated with support for different fairness criteria. In particular, we find differences between the male and female, young and old, high and low educated, student and non-student, and high and low income participants. We therefore contribute to the emerging empirical literature showing it is unlikely that all individuals share the same fairness ideals (Cappelen et al. 2007; Fisman et al. 2007).

Third, although it is a commonly-held belief that left-wing voters are more egalitarian and right-wing voters are more efficiency-minded, there is surprisingly little empirical evidence on how voters differ with respect to their distributive preferences. Notable exceptions are Fisman et al. (2017) who show that conservatives in the United States make a different equity-efficiency trade-off, and Kerschbamer and Müller (2020) who find that inequality-averse, altruistic, and maxi-min subjects are more likely to express left-wing political attitudes, both in a stakeholder framework. In our study, we relate the distributive ideals of individuals to their political preferences and show that right-wing voters are indeed more efficiency-minded and left-wing voters more egalitarian. There is a noticeable break in this trend at the extremes, both far-left and far-right wingers are mostly egalitarian. In line with expectations from the Hotelling-Downs political competition models, we find that the German established parties are close to the median voter.

Fourth, we show that our experimentally-elicited fairness types are meaningful measures of underlying political and policy preferences. We show that rightist parties are more likely to attract efficiency-minded individuals than leftist parties. These same efficiency-minded individuals are less supportive of governmental redistribution and of higher taxation. Lastly, efficiency-minded individuals are less likely to donate to charity than maxi-min and egalitarian types. The predictive power of our fairness measures is considerable, even when controlling for a battery of individual characteristics. These findings add to the discussion on how laboratory measures relate to field behavior.

Furthermore, we present evidence suggesting that student populations hold different fairness views than the rest of the population. This finding suggests that previous studies in empirical social choice have systematically overestimated the importance of maxi-min and efficiency-minded types. These findings thus also contribute to the current discussion in the experimental literature on the generalizability of results obtained from student samples.

Notes

Decision makers in our experiment are not directly paid for their choices. One could therefore argue that only if people have social preferences, that is, if they care about the payoffs to other people, will their decisions actually be incentivized. There is, however, abundant evidence that people do care about payoffs of others in economically-relevant ways. Hence, pecuniary income for others can serve as incentives for third-party observers who do not have a personal direct stake in the allocation.

In a meta-study Engel (2011) finds i.e., that females give significantly more than men in dictator games. However, studies that account for the fact that men and women also make systematically different equity—efficiency trade—offs typically find little evidence for gender effects, see Andreoni and Vesterlund (2001), Kerschbamer and Müller (2020), Müller (2019).

By now, there is ample evidence that rejects the assumption of narrow money-maximizing behavior. Theoretical evidence for the view that “moral” preferences have evolutionary roots was given by, for example, Alger and Weibull (2013). There is also convincing evidence from biology that supports this statement, see Wright (2010) for an overview.

For an excellent overview, please consult Gaertner and Schokkaert (2011).

In a related study, Kerschbamer and Müller (2020) study distributional preferences of stakeholders in the GIP.

Screenshots of the design can be found in the Appendix.

The experiment presented in this paper was part of a larger set-up, combining two different experiments on fairness preferences. In each of the two parts, subjects made two choices about the distribution of money between two other randomly-selected, anonymous respondents. The second part of this experiment however involved two choices with risk in the final allocation. This second part is thus conceptually very different from the first part and will not be discussed in this paper.

We allowed for maxi-min types to be indifferent between the egalitarian and the maxi-min option in choice 2. That is, we do not assume that maxi-min subjects necessarily follow the stricter lexicographic interpretation of the maxi-min rule. Our conclusions are however hardly affected by this definition.

Due to privacy concerns this dataset does not allow us differentiate between Berlin and Brandenburg (the state surrounding Berlin), so that inhabitants of Berlin are coded as living in former East Germany.

English translations of complete questions can be found in the Appendix.

The distribution of answers to each of these questions is shown in Table 5.

We again use ordinary least squares since the marginal effects are easier to interpret. The coefficients from an ordered logit model are very similar in sign and significance and can be found in the tables in the Appendix. The Appendix also shows the same regression as displayed in Table 3, but now using only the first or only the second choice in the experiment to assign types. The results are very similar.

One could argue that this finding is surprising, because East Germany experienced the detriments of state-communism. Nevertheless, our finding is in line with research by Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln (2007) who show that former East Germans show greater support for state interventions than their West-German counterparts. Former East Germans seem to trust the current government, without fearing that an intervention to reduce inequality could lead to the repetition of past mistakes.

Table 8 in the Appendix reports a more detailed comparison of political extremists along different socio-demographic characteristics.

The last national election to take place before our experiment was in September 2013, and the last GIP wave to ask about this election before our experiment was in September 2015. From left to right, the party Die Linke is a democratic, socialist party. Its roots can directly be traced back to the former ruling party in communist East Germany, the SED. The other left-wing party is The Greens (Bündnis 90 - Die Grünen), that was formed in 1993 and mainly focuses on environmental topics and social sustainability. Closer to the political center is the Social Democrats of Germany (SPD). The SPD is by far the oldest party in Germany and mainly focuses on social policy and traditionally represents the working class. The other large party at the center of the German party system is the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). This party, together with its Bavarian ally - the Christian Social Union (CSU) - forms the Union. Most of the political leaders after World War II were members of the Union. A traditional, smaller coalition partner of the Union is the Free Democratic Party (FDP), which supports liberal values and focuses on civil liberties, human rights, and free market policies. On the right-side of the political spectrum there are currently two parties: Alternative for Germany (AfD) a populist, right-wing to far-right party. This party formed as Euro-skeptic party in 2013 and increased its popularity in the wake of the refugee crisis around 2015. The National Democratic Party of Germany (NDP)is a right-wing nationalistic party with a left-wing economic policy platform. It is strongly anti-immigration and anti-establishment, but currently does not hold any parliamentary seats.

The similarities between the far-left and far-right in this survey seem surprising. We therefore compared these groups further. If we take the most ideologically extreme groups in terms of self-placement, i.e. compare those who answer 1 to those who answer 11, we find no statistical differences in age, location or gender, but some indications about education. However, numbers of observations are small. If we take the two most extreme groups in terms of self-placement, i.e. answers 1 and 2 compared to 10 and 11, educational and gender differences appear. The extreme left appears to be slightly better educated and to attract more females. We report these tests in the Appendix, Sect. A.7.

The 2015 micro-census data was obtained from the German statistical agency (Statistisches Bundesamt) via https://www-genesis.destatis.de/, data code 12211.

Note that, for data privacy concerns, the GIP groups several small states with a neighboring state into a common categories. We adjusted the micro-census accordingly.

The participants cannot choose the exact charitable organization, all donations are shared equally among the Red Cross, WWF and the SOS Kinderdorf.

A different type of efficiency preference would be a concern for the sum of utilities in a society, i.e. utilitarianism. Utilitarians might actually be more likely to donate in certain settings due to the curvature of utility functions. However, since we measure efficiency-concerns via choices over sums of money, we define the efficiency concern as relating to monetary efficiency. Therefore, we predict that efficiency–seekers are less likely than maxi–min and egalitarians to donate money. This prediction should hold here, since charitable organizations need to pay fixed costs and are thus not a perfectly efficient redistribution mechanism.

References

Aguiar F, Becker A, Miller L (2013) Whose impartiality? An experimental study of veiled stakeholders, involved spectators and detached observers. Econ Philos 29(02):155–174

Alesina A, Fuchs-Schündeln N (2007) Goodbye lenin (or not?): the effect of communism on people’s preferences. Am Econ Rev 97(4):1507–1528

Alger I, Weibull JW (2013) Homo moralis–preference evolution under incomplete information and assortative matching. Econometrica 81(6):2269–2302

Almås I, Cappelen AW, Tungodden B (2019) Cutthroat capitalism versus cuddly socialism: Are americans more meritocratic and efficiency-seeking than scandinavians? Journal of Political Economy

Amiel Y, Cowell FA, Gaertner W (2009) To be or not to be involved: a questionnaire-experimental view on Harsanyi’s utilitarian ethics. Soc Choice Welf 32(2):299–316

Andreoni J, Vesterlund L (2001) Which is the fair sex? Gender differences in altruism. Q J Econ 116(1):293–312

Becchetti L, Antoni GD, Ottone S, Solferino N (2011) Spectators versus stakeholders with or without veil of ignorance: the difference it makes for justice and chosen distribution criteria. Working Paper

Bellemare C, Kröger S, Van Soest A (2008) Measuring inequity aversion in a heterogeneous population using experimental decisions and subjective probabilities. Econometrica 76(4):815–839

Blom AG, Gathmann C, Krieger U (2015) Setting up an online panel representative of the general population the german internet panel. Field Methods, 27(4):391–408

Blom AG, Bosnjak M, Cornilleau A, Cousteaux A-S, Das M, Douhou S, Krieger U (2016) A comparison of four probability-based online and mixed-mode panels in Europe. Soc Sci Comput Rev 34(1):8–25

Blom AG, Herzing JME, Cornesse C, Sakshaug JW, Krieger U, Bossert D (2017) Does the recruitment of offline households increase the sample representativeness of probability-based online panels? evidence from the german internet panel. Social Science Computer Review, 35(4):498–520

Bolton GE, Ockenfels A (2000) Erc: a theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. Am Econ Rev, pp 166–193

Bosmans K, Schokkaert E (2004) Social welfare, the veil of ignorance and purely individual risk: An empirical examination. Research on Economic Inequality 11:85–114

Brafman RI, Tennenholtz M (1997) On the axiomatization of qualitative decision criteria. In: AAAI/IAAI, pp 76–81. Citeseer

Cappelen AW, Hole AD, Sørensen E, Tungodden B (2007) The pluralism of fairness ideals: An experimental approach. American Economic Review, 97(3):818–827

Cappelen AW, Konow J, Sørensen E, Tungodden B (2013) Just luck: an experimental study of risk-taking and fairness. Am Econ Rev 103(4):1398–1413

Cappelen AW, Nygaard K, Sørensen E, Tungodden B (2015) Social preferences in the lab: a comparison of students and a representative population. Scand J Econ 117(4):1306–1326

Cettolin E, Riedl A (2016) Justice under uncertainty. Manage Sci 63(11):3739–3759

Charness G, Rabin M (2002) Understanding social preferences with simple tests. Q J Econ, pp 817–869

Croson R, Konow J (2009) Social preferences and moral biases. J Econ Behav Org 69(3):201–212

Engel C (2011) Dictator games: a meta study. Exp Econ 14(4):583–610

Engelmann D, Strobel M (2004) Inequality aversion, efficiency, and maximin preferences in simple distribution experiments. Am Econ Rev, pp 857–869

Fehr E, Schmidt KM (1999) A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Q J Econ, pp 817–868

Fisman R, Kariv S, Markovits D (2007) Individual preferences for giving. Am Econ Rev 97(5):1858–1876

Fisman R, Jakiela P, Kariv S (2017) Distributional preferences and political behavior. J Public Econ 155:1–10

Frohlich N, Oppenheimer JA (1990) Choosing justice in experimental democracies with production. Am Polit Sci Rev 84(02):461–477

Frohlich N, Oppenheimer JA (1992) Choosing justice: an experimental approach to ethical theory, vol 22. University of California Press, California

Frohlich N, Oppenheimer JA, Eavey CL (1987a) Choices of principles of distributive justice in experimental groups. Am J Polit Sci, pp 606–636

Frohlich N, Oppenheimer JA, Eavey CL (1987b) Laboratory results on Rawls’s distributive justice. Br J Polit Sci 17(1):1–21

Gaertner W, Schokkaert E (2011) Empirical social choice: questionnaire-experimental studies on distributive justice. Cambridge University Press

Green JE (2013) Rawls and the forgotten figure of the most advantaged: in defense of reasonable envy toward the superrich. Am Polit Sci Rev 107(1):123–138

Gsottbauer E, Müller D, Müller S, Trautmann S, Zudenkova G (2020) Social class and (un)ethical behavior: Causal versus correlational evidence. Innsbruck Working Paper Series

Harsanyi J (1953) Cardinal utility in welfare economics and in the theory of risk-taking. J Polit Econ 61(5):434

Harsanyi JC (1955) Cardinal welfare, individualistic ethics, and interpersonal comparisons of utility. J Polit Econ 63(4):309–321

Kahneman D, Knetsch JL, Thaler RH (1986) Fairness and the assumptions of economics. J Bus, pp S285–S300

Kerschbamer R, Müller D (2020) Social preferences and political attitudes: an online experiment on a large heterogeneous sample. J Public Econ, pp 182

Konow J (2000) Fair shares: accountability and cognitive dissonance in allocation decisions. Am Econ Rev, pp 1072–1091

Konow J (2003) Which is the fairest one of all? A positive analysis of justice theories. J Econ Lit 41(4):1188–1239

Konow J (2009) Is fairness in the eye of the beholder? An impartial spectator analysis of justice. Soc Choice Welf 33(1):101–127

Kuziemko I, Norton MI, Saez E (2015) How elastic are preferences for redistribution? Evidence from randomized survey experiments. Am Econ Rev 105(4):1478–1508

Michelbach PA, Scott JT, Matland RE, Bornstein BH (2003) Doing rawls justice: An experimental study of income distribution norms. American Journal of Political Science, 47(3):523–539

Mitchell G, Tetlock PE, Mellers BA, Ordonez LD (1993) Judgments of social justice: compromises between equality and efficiency. J Personal Soc Psychol 65(4):629

Müller D (2019) The anatomy of distributional preferences with group identity. J Econ Behav Org 166:785–807

Posner RA (1983) The economics of justice. Harvard University Press

Rawls J (1971) A theory of justice. Harvard University Press, Harvard

Roemer JE (1996) Egalitarian perspectives: essays in philosophical economics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Schildberg-Hörisch H (2010) Is the veil of ignorance only a concept about risk? An experiment. J Public Econ 94(11):1062–1066

Smeets P, Bauer R, Gneezy U (2015) Giving behavior of millionaires. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112(34):10641–10644

Traub S, Seidl C, Schmidt U, Levati M (2005) Friedman, harsanyi, rawls, boulding-or somebody else? an experimental investigation of distributive justice. Soc Choice Welf 24(2):283–309

Trautmann ST, van de Kuilen G, Zeckhauser RJ (2013) Social class and (un) ethical behavior a framework, with evidence from a large population sample. Perspect Psychol Sci 8(5):487–497

Wright R (2010) The moral animal: why we are, the way we are: the new science of evolutionary psychology. Vintage

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank seminar participants in Mannheim and Rotterdam and Alexander Cappelen, Ernst Fehr, Verena Fetscher, Hans Peter Grüner, and Erik Sørensen for helpful comments. We are indebted to the GIP team, in particular to Franziska Gebhard for logistical support during the experiment. Financial Support from the German research foundation (DFG, SFB 884) is gratefully acknowledged.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Screenshots

1.2 Translated instructions

This part of the questionnaire is about four proposals on the distribution of money. The amounts of money are real and can be paid to randomly selected participants of the questionnaire. We kindly ask you to select a proposal on how to divide the money between two other participants of the questionnaire in each of the four [two] decision situations. We will call these two participants person 1 and person 2. All other participants, not only you, will make four such proposals. Not all decisions are going to be paid out for real in the end. Instead, the computer will randomly choose 50 proposals made by the participants for each of the 4 decisions. This means that at the end 4 times 50 that is 200 proposals will be paid out for real. We estimate that 3500 people will take part in this questionnaire (Figs. 6, 7).

For each randomly selected proposal, two randomly chosen participants will be selected who will receive the proposed monetary amounts. One person will be randomly assigned to the role of person 1 and to the other to the role of person 2. Each of the two will then receive the payoff of corresponding to the relevant proposal. Each of the proposals made can be randomly selected for the actual payoff by the computer. So it could be that your proposal will be chosen and that two other participants will receive exactly as much money as you proposed. You could also be selected and receive the payoff that another participant proposed. In this case the money will be directly transferred to your account at the GIP. None of the participants can be chosen more than once to receive money. All decisions made will of course stay anonymous. We will notify the winners.

Below four proposals (A, B, C and D) on how to distribute money between person 1 and person 2 are depicted. We kindly ask you to indicate which of these alternatives you prefer.

-

Alternative A: person 1 should receive 10 Euros; person 2 should receive 9 Euros.

-

Alternative B: person 1 should receive 15 Euros; person 2 should receive 7 Euros.

-

Alternative C: person 1 should receive 8 Euros; person 2 should receive 8 Euros.

-

Alternative D: person 1 should receive 16 Euros; person 2 should receive 2 Euros.

Please pay attention that your decision can affect how much two other (anonymous) randomly selected participants actually receive. Which alternative do you prefer?

1.3 Translated wording of relevant GIP questions

Income differences

Now we will deal with a different topic. Please indicate to which extent you agree with the following statement:

The government should take measures to reduce income differences. Keep in mind that these measures must be financed by taxes that would lead to reductions of one’s salary.

You can only give one answer:

-

1.

I strongly agree.

-

2.

I agree.

-

3.

I am indifferent.

-

4.

I disagree.

-

5.

I strongly disagree.

Tax equity

Should people who work more than others and therefore also earn more pay less or more taxes than they currently do?

-

1.

Pay far less taxes than they currently do.

-

2.

Pay slightly less taxes than they currently do.

-

3.

Pay the same amount of taxes that they currently do.

-

4.

Pay slightly more taxes than they currently do.

-

5.

Pay a lot more taxes than they currently do.

1.4 The demographic characteristics of the German internet panel

In this Appendix, we compare our most restrictive sample of GIP participants, the consistent types, to the 2015 German micro-census in terms of age, gender and state of residence.Footnote 19 We report results from \(\chi ^2\) goodness-of-fit tests that compare the frequency of demographics in our sample and the micro-census. The first part of Table 4 presents frequencies of different age groups between the ages of 20 and 64. All things considered, the distribution of age is roughly the same in our sample compared to the census: In no bracket is the difference larger than 2 percentage points, which gives us confident that our sample covers the full distribution of age in the German population. Nevertheless, the sum of smaller differences in each bin leads to significant \(\chi ^2\) test (\(p=0.001\)). The distributions of gender on the other hand are statistically indistinguishable (\(p=0.511\)). Regarding the geographical distribution of our participants, we again find no significant difference to the distribution of respondents over the different states (\(p=0.213\)).Footnote 20

Taken together, we find that our participants exhibit similar distribution of key socio-demographics as those in the micro-census, with some exceptions in certain age brackets. Overall, it seems fair to say that the GIP provides a large and heterogeneous sample with participants from all walks of life and that it does not appear to systematically ignore specific demographic groups of the German society.

1.5 Additional results

In this section we repeat the main regressions in the form of ordered logistical regression to show that our conclusions are not affected by the choice of the empirical model. Table 5 shows the distribution of support for the main policy variables. The three different versions of the “Inequality” questions in waves 15, 17 and 21 show that the support for redistribution is fairly stable over time.

Figure 8 depicts the frequencies by left, center and right party. The parties are grouped in the same way as in Fig. 5b based on whether they are leftist (Die Linke, Grüne/Bündis ‘90), center parties (SPD, CDU/CSU, FDP), or right-wing (AfD, NPD).

1.6 Revealed charitable behavior and fairness types

In this section, we present results regarding the correlation between fairness types and revealed charitable behavior. All participants of the GIP receive a flat payment of four euro on their experimental account for every wave they participate in. Participating in all waves in a year yields an extra bonus of 10 euros, the bonus is reduced to 5 euro if one wave is missed and 0 if more than one wave is missed in any given year. Every six months the experimental account is automatically paid out to the participants. Participants can have the money transferred directly to their bank account, receive the corresponding value in Amazon vouchers, or donate it to charity.Footnote 21 Participants set their pay-out option when registering for the GIP, but can change their setting at any time. Before payment, respondents receive an email that asks them to review their account settings with regard to the payment method, but only about 2% of the participants change their settings after receiving this email. Below we will analyze the payout in October 2015, in which 14.3% of all participants chose to donate their money to charity.

Giving to charity should increase with one’s concern for others’ well-being. Egalitarians are willing to actively reduce incomes in order to achieve equality. Consequently, we expect egalitarians to be more likely to donate than the other types. In contrast, maxi-min types are expected to care about others’ welfare, but will not violate strict Pareto dominance, creating a similar but possibly smaller incentive to donate. Efficiency-minded individuals should show the lowest propensity to donate, as they do not show an indication of favoring income to those less-well-off over income to others. This difference may be reinforced by the possible inefficiencies found in charities—not every euro given to charity actually benefits the poor. Consequently, efficiency-minded participants should be less likely to give to charity than either of the two other types (Table 6).Footnote 22

We test these conjectures in Table 7. We regress the dummy whether a person has donated to charity or not, on a set of control variables like age, income (in 1000 euros), gender, education levels (according to the groups used before) and the fairness-type dummies. Additionally, we also control for trust in the government and the exact amount the participants received (which depends on how many waves the participant answered). As before, egalitarians serve as the reference group. We find that egalitarians are significantly more likely to donate to charity than both maxi-min and efficiency types. The first column shows the results using an OLS regression as done in the main text, the corresponding Logistic regression in column (2). The coefficient on efficiency in column (1) indicates that the donation rate decreases by six percentage points from the unconditional baseline of approximately 13%. The doubling of the likelihood of donations of the egalitarian type compared to the efficiency-minded type is both statistically and economically significant. As expected, the maxi-min types are located between efficiency-minded participants and egalitarians.

Additionally we find that older, more educated and high income individuals are more likely to donate to charity. In particular, the finding that richer people are more likely to donate money is interesting. In that sense, our experiment also provides suggestive evidence against the popular conclusion that the rich are more selfish (Trautmann et al. 2013; Smeets et al. 2015; Gsottbauer et al. 2020). To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to demonstrate the predictive power of third party spectator fairness views for field behavior, which is particularly interesting because these fairness ideals are philosophically-motivated, abstract concepts.

1.7 Comparing extreme left- and right- wingers

Extreme left- or right-wingers appeared fairly similar in terms of fairness preferences in the analysis in the main text, which raises intriguing questions about the similarities and the differences of political extremist. We therefore provide some additional comparisons of extreme left- and right-wingers in Table 8. We use two different definitions of extremists: a strict definition that only looks at those who answer either 1 or 11 on the 1-11 point scale, and a wide definition that considers those who answer (1,2) or (10,11). For each comparison, we report the \(\chi ^2\) statistics and corresponding p-values in the table. Obviously, the small number of observations (30 left- and 17 right-wingers in the former case and 124 left- and 42 right-wingers in the latter case) requires us to interpret the conclusions with caution.

We find that females are in general less likely to hold extremist views than males. Moreover, female extremists are more likely to be left- and than right-wingers. East Germans are more likely to classify themselves as extremists in general than West Germans (East Germans make up around 20% of the population and GIP participants). This effect is even stronger among right-wing extremists than left-wing ones. Next, we find that extremists from both sides are more likely to be above average age (the variable young equals 1 if the participant is younger than the median age). Right-wingers are older than left-wingers. Looking at education, it turns out that left-wingers are significantly more educated than right-wingers (the variable education equals 1 if the education level is either 3 or 4 on the 1 to 4 scale of the main text). We find very little evidence for a systematic difference in religious affiliations between left- and right-wingers but also between extremists and other GIP participants (the frequency of Catholics and Protestants in the GIP is around 20% in both cases).

1.8 Robustness check: assignment of types

Table 9 repeats the analysis of Table 3, but assigns types either based on the first (columns 1–4) or the second choice (columns 5–8) only. The main variable of interest is the coefficient on efficiency. Comparing the coefficients and significance levels, we see that in all regressions efficiency types are less likely to support government intervention as we already found in Table 3 before. It seems that the effects are somewhat stronger for the second distributional choice than for the first one.

When comparing behavior in the first and the second choice, we find that 134 subject switched from the efficient allocation to the maxi-min allocation. The efficiency choice had a total value of €22 in the first, but only €18 (only €1 more than maxi-min) in the second choice. That is, choosing the efficient allocation was less attractive in the second choice compared to the first. It thus seems that the subjects who chose to remain with the efficient distribution in the second choice display an even higher preference for efficiency and also differ more strongly from the egalitarians in their political attitudes.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Müller, D., Renes, S. Fairness views and political preferences: evidence from a large and heterogeneous sample. Soc Choice Welf 56, 679–711 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-020-01289-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-020-01289-5