Abstract

This paper considers the design of taxes on real money balances and bank payment services, when realistically, the household can use either cash or a bank payment account for the purchase of different varieties of goods. These taxes, plus a consumption tax, fund a government revenue requirement. We find that generally, real money balances and bank transaction fees should be taxed, and at different rates, i.e. the tax system should not leave the choice of payment services undistorted. For a wide class of time transactions cost technologies, including the Baumol-Tobin case, fees should be taxed at a lower rate than real money balances, and the tax on real money balances should be positive. However, it is possible that fees should be subsidized. The rate of tax on fees has no simple relationship to the optimal consumption tax, and can be higher or lower. A Corlett-Hague type intuition for these results is also developed, which relies on the concept of a virtual time endowment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper addresses a relatively neglected issue, the optimal taxation of payment services. By payment services, we mean the services provided by the banking system that facilitate payment for goods and services. There is of course, a large literature on the optimal taxation of fiat money, the so-called inflation tax literature. This literature focuses on conditions for the zero taxation of cash, i.e. the Friedman rule, which says that the nominal interest rate should be zero. In this literature, however, it is assumed, without exception, that cash is the only medium of payment, or that some goods can be bought on credit, and so the issue of how services provided by the banking system should be taxed is not addressed.Footnote 1

This focus on cash may have been justified years ago, when the use of a bank account meant the writing of a check, and most transactions were made using cash. However, the focus on the literature on cash is clearly increasingly unrealistic because technological advances have allowed so-called electronic transfer of funds at the point of sale, by using credit and debit cards. These services are rapidly overtaking cash as means of payment for retail transactions.Footnote 2

For example, based on a large-scale payment diary survey, conducted between 2009 and 2012 in seven major countries, Bagnall et al. (2016) report that the share of the number of transactions with cash is on average of 62% (between 46 and 82%, varying by country), while its value share is on average of 35% (between 15 and 65%).Footnote 3 As expected, this shows that a larger number of smaller transactions are made by cash, and that larger value transactions are made by other means. In recent years, the share of cash has fallen further. For example, in the US, the share of cash in retail transactions fell from 40% in 2012 to 32% in 2015 (Matheny et al. 2016).

On the other hand, it is unlikely that cash will disappear altogether as a medium of payment; as reported by the Cash Product Office of the US Federal Reserve, “In 2015, cash continued to dominate small-value transactions, with cash being used for more than 50% of transactions under $25....(and) for more than 60% of purchases under $10.” (Matheny et al. 2016, p6). Again, in another large scale payment diary survey in the Euro Area in 2016, for a subset of EU countries, Esselink and Hernández (2017) report an even higher ratio of cash usage than Bagnall et al. (2016), for countries such as Cyprus, Greece, and Malta, which used above 70% cash by transactions value.

Does the choice of payment method matter? At a macroeconomic level, Philippon (2015) and Bazot (2018), show that the costs of financial intermediation for the banking sector in the US and Europe are considerable; for the US, they estimate these costs at around 2.5% of assets intermediated. The specific costs of operating payments services such as Mastercard, Visa etc are also large; for example a 2012 study by the European Central Bank estimated the average resource cost of non-cash payment systems across EU-27 at about 1% of GDP (Schmiedel et al. 2012). This translates to about 2.8% of the value of consumption facilitated by payments systems.Footnote 4 But, these costs have to be set against the benefits to consumers in terms of greater time saving, convenience, and security.

Given these two methods of payment for goods, the question then arises as to how they should be taxed, if a government has to use distortionary taxes to raise revenue. This paper studies the optimal tax structure in a model that combines the transaction cost theory of the demand for money (for example Correia and Teles (1996), Teles (2003)), with the model of Freeman and Kydland (2000), which allows for substitution between cash and use of bank accounts. In our model, the household demands different varieties of goods in different quantities, and these can be paid for either by cash, or by electronic transfer of funds at the point of sale, provided by a bank account. We will call this account a payment account (PA).Footnote 5

The time transactions cost of using cash is modeled in the usual way, by assuming that goods bought with cash require a time input from the household, which can be lowered by holding a higher stock of real money balances.

We model the cost of using a PA by assuming that the bank charges a per transaction fee to the seller of the good, which is then passed on to the consumer by the seller.Footnote 6 To make our point as clearly as possible, we assume the use of the PA requires no time input from the household. While this is an abstraction, it is increasingly close to reality, with so-called ”contactless” payment via debit card, and mobile phone apps for management of bank accounts becoming increasingly widespread.

To ensure that the choice between cash and a PA is not trivial, we assume that cash has a real resource cost, as in Correia and Teles (1996). The reason for this is that if cash were free, the optimal inflation tax would be zero, and then the household would use only cash.Footnote 7 We then show that in equilibrium, there will be a ”switch point” above which varieties in greater demand will be bought using the PA.

The government has a fixed revenue requirement in each period, and to finance this, can tax the payment fees charged by banks, and can also tax real money balances via an inflation tax. In addition, the government has the use of a consumption or income tax. In this setting, we characterize optimal payment service taxes i.e. the structure of taxes on both real money balances and the fees, as well as the consumption tax. Our main contribution is to develop simple formulae for the optimal ad valorem taxes on both real money balances and transactions fees. It turns out that the structure of taxes on these two payment methods only depend on the characteristics of the time transactions cost of cash, not the form of the household utility function.

Specifically, in our setting, the time used for transactions is a function of the quantity of goods bought with cash (cash purchases), and real money balances. Then, both the sign of each tax, and the ratio of these two taxes, depend only on the properties of the time transactions cost function. Assuming that this function is homogeneous of degree k, both taxes are decreasing in k. The tax on cash is also increasing in elasticity of the marginal time transactions cost of additional cash purchases with respect to real money balances. Similarly, the tax on fees is also increasing in elasticity of the marginal time transactions cost of additional cash purchases with respect to cash purchases. If \(k\le 1\), the tax on real money balances is always positive, but the tax on fees may be negative. We also find conditions on the time transactions cost of cash such that the taxes are positive, and that the tax on cash is always higher than the tax on fees.

The general intuition for these results is based on the concept of a “virtual” time endowment. Specifically, we can reduce the tax design problem for the government to a completely standard one, except that the household has, instead of a fixed time endowment, a “virtual” time endowment that is endogenous, and depends on k and the share of goods bought with cash and real money balances. This virtual time endowment is of course not directly taxable, but can be indirectly taxed by taxes on payment services insofar as they affect the share of goods bought with cash and real money balances. For example, a tax will be positive if it indirectly reduces the virtual time endowment. Thus, in general terms, the intuition is similar to that of Corlett and Hague (1953), who argue that taxes should be set to indirectly tax non-taxable leisure. However, the specific mechanism is quite different; in Corlett and Hague (1953), the key variable is the degree of complementarity in preferences between leisure and the taxed goods. Here, it is the properties of the transactions technology that are key.

We also relate our results to the Diamond and Mirrlees (1971) production efficiency result. One can interpret the transactions technology in our model as a form of household production, where inputs in the form of cash balances and PAs, combined with market purchases and time, produce final consumption. Our result is that even with a constant returns transactions time technology, these inputs to final consumption should generally be taxed. In other words, the Diamond–Mirrlees principle that inputs should not be taxed with constant returns in production does not extend to the household in this context.

Our results also have implications for the literature on the optimal inflation tax. For example, we show that the findings of Correia and Teles (1996) are not robust to introducing substitutability between cash and PAs.Footnote 8 Specifically, we show that when both payment media are used, real money balances should be taxed even when \(k=1\), in contrast to their findings when cash is the only medium of payment.Footnote 9

We then turn to some numerical simulations, using a calibrated version of the model. We find that, consistently with our analytical results, both the inflation tax and the tax on fees decrease markedly as the returns to scale in transactions costs increase from zero to one. The results show also that both inflation tax and the tax on fees decrease as the bank fee increases. This is interesting as the move away from cash that we currently observe is ultimately driven by technological innovation that reduces fees. Moreover, when the fee is large or when returns to scale are close to one, the tax on fees can be negative i.e. bank fees should be subsidized. We also find that the tax on bank fees can be greater or less than the rate of consumption tax although both taxes are of the same order of magnitude.

Our findings have some implications for the current policy debate on the taxation of banks, especially in Europe, where it is the view of many, including the European Commission, that banks are under-taxed, because many of their services are exempt from VAT.Footnote 10 In this debate, it is largely assumed that within a consumption tax system, such as a VAT, it is desirable to tax financial services at the standard rate of VAT e.g. Ebrill et al. (2001).Footnote 11 Our results provide some support for this position, in that we find that payment services provided by banks should be taxed positively in a number of cases.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a summary of related literature. Sections 3–5 outline the model. Section 6 presents the main results. Section 7 presents a calibrated version of the model, and Sect. 8 concludes.

2 Related literature

Our paper relates to a number of literatures. First, there is a small literature directly addressing the taxation of payment services (Grubert and Mackie 2000; Jack 2000; Auerbach and Gordon 2002). With the exception of Auerbach and Gordon (2002), these papers use a simple two-period consumption-savings model without an explicit production sector, and assume that payment services are consumed in fixed proportion to aggregate consumption.Footnote 12 In this setting, it is straightforward to show that if there is a pre-existing consumption tax at the same rate in both periods, the marginal rate of substitution between present and future consumption is left unchanged if payment services are taxed at the same rate as consumption.

Auerbach and Gordon (2002) consider a multi-period life-cycle model of the consumer where purchase of goods requires payment services, which themselves are produced using other inputs. Payment services are assumed to be demanded in strict proportion to consumption. They show that if there is initially only a labor income tax imposed on the household, then this is equivalent to a value-added tax if and only if the payment services consumed by the household are taxed at the same rate as other goods.Footnote 13

There are, however, a number of restrictive assumptions implicit in these existing models. First, and foremost, they do not allow the household to choose between cash and other payment services. Second, other taxes are assumed fixed, not optimized, and it is implicit that the existing taxes are non-distortionary, because the analysis proceeds by finding conditions under which taxation of payment services does not introduce any further distortions. By contrast, we take an explicit tax design approach to the question, investigating the second-best tax structure.

The second related literature is on the optimal inflation tax. This literature is mature, and there are a number of well-known reasons why the Friedman rule may not hold and it may be optimal to tax real money balances. These include the existence of pure profit due to decreasing returns to scale, imperfect competition in the product market, or tax evasion (see for example, the surveys by Kocherlakota 2005; Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe 2010). Our model has none of these features, but we still find violation of the Friedman rule, for completely different reasons. Moreover, in spite of the large literature on the Friedman rule, we are not aware of any paper that studies the optimal tax structure on both cash and non-cash payment instruments.

A third related literature is the one on optimal taxation with household production (Sandmo 1990; Piggott and Whalley 2001; Kleven et al. 2000). This literature has a number of similarities to ours. Specifically, the complementarity of purchased inputs and household time in household production is an important determinant of the optimal tax structure, and also, there is generally production inefficiency; that is, taxes distort the choice of inputs to household production. The relationship of our results to theirs is further discussed in Sect. 6 below.

Finally, there is a recent literature studying banks that engage in socially undesirable activities such as excessive risk-taking.Footnote 14 The main finding is that these should be corrected by Pigouvian taxes (or regulations) that apply directly to these decision margins, such as taxes on borrowing or lending. Our work is distinct from this line of inquiry, as the banking sector has no external effects in our setting; we are concerned with the design of taxes to raise revenue. So, we are studying ”boring banks” in the terminology of Aigner and Bierbrauer (2015), to which our paper is also related. They, however, focus on tax incidence issues, whereas we are concerned with tax design.

3 The model

The model is a modified version of the Freeman and Kydland (2000) model. This model has a number of attractive features which generates an equilibrium where cash and PAs co-exist, and where small items will be purchased with cash and larger items will be purchased with PAs. These are: (i) the consumption bundle is sorted by the sizes of the purchases, (ii) there is a time cost of using cash, and (iii) there is a fixed cost per transaction of using the PA. All these features are needed for a non-trivial analysis of the effects of payment services taxes on household behavior. The exact relationship of our set-up to Freeman and Kydland (2000) is discussed further in Sect. 3.5 below.

3.1 Set-up

A large number of identical households live for periods \(t=1,\ldots \infty .\) In each period, they consume a number of different varieties of a consumption good \(j\in \left[ 0,1\right] \), supply labor, and can also hold cash, bank deposits and government bonds. The banks take deposits and use them to buy government bonds, and also provide payment services to depositors. The government issues bonds and sets taxes to finance an exogenous level of public good provision in each period.

3.2 Firms and banks

In each period, a single competitive firm produces an intermediate good from labor, where one unit of labor produces one unit of the good. One unit of this intermediate good can be transformed by a seller j into one unit of variety \(j\in \left[ 0,1\right] \) of the consumption good. All sellers are perfectly competitive price takers and thus set a price of variety j equal to the price of the intermediate good.

A single competitive bank offers a PA to the households. It takes nominal deposits \(D_{t}\) from the household in period t, and purchases government bonds \(B_{t}^{B}\). The bank also provides payment services, using the intermediate good as an input. Specifically, any variety j can be purchased using the PA at a cost of f per purchase in units of the intermediate good. As the bank is competitive, we assume that the cost is just passed on to the household, without any mark-up.

This fee can be taxed at rate \(\tau _{t}^{f}\) so the household faces a cost \(f\left( 1+\tau _{t}^{f}\right) \) if it chooses to purchase variety j using a PA. We interpret f as covering all costs associated with the banking system. So, f measures, inter alia, the costs of physical bank branches, and all labor and other costs associated with PAs. Included in this would be the bank interchange fee that a card-issuing bank charges the seller of the good for the use of the card.Footnote 15

Finally, the stock of bonds outstanding at t pay a nominal interest rate \(i_{t}\). As the bank is perfectly competitive, this is also the return on deposits.

3.3 Households

The single infinitely lived household has preferences over levels of consumption goods and leisure \(t=0,..\infty \) of the form:

where \(c_{t}(j)\) is the level of consumption of variety j in period t, \(l_{t}\) is the consumption of leisure. We assume \(u\left( c,l\right) \) is strictly increasing and strictly concave, and that \(u_{cl}\ge 0\), where subscripts denote derivatives. Also, \(0<\beta <1\) is a discount factor.

The fixed coefficients specification for the commodity index follows Freeman and Kydland (2000); it allows for consumption levels of the different varieties to vary in an analytically tractable way. In particular, all varieties will be consumed in fixed proportions to some c, i.e.

Note that aggregate consumption is \(\int _{0}^{1}c\left( j\right) dj=c\).

The household can use either cash or the PA to make purchases. The advantage of using the PA is that relative to cash, it economizes on household time. To make this point as cleanly as possible, we assume that use of the PA requires no time. This is an increasingly close approximation to reality, as many card transactions are contactless (i.e. do not even require a security (PIN) number) and accounts can be managed via smart-phone apps. On the other hand, using cash is costly in terms of time, for several reasons that are well-documented in the literature; it has to be physically withdrawn from ATMs, stored securely, etc.

We capture this by supposing that a volume \(x\equiv 2c\int _{T}jdj\) of consumption bought with cash requires \(s\left( x,m\right) \) units of time, where \(T\subset \left[ 0,1\right] \) is the subset of goods that are bought with cash, and m is real money balances, defined below. We assume that s is twice continuously differentiable, increasing in x and decreasing in m. We will also assume that an increase in the use of money reduces the marginal transactions cost i.e. \(s_{xm}<0\). This general specification \(s\left( x,m\right) \) of the time transactions cost of cash is standard in the literature, and includes a number of well-known special cases. For example, with the inventory-theoretic demand for money of Baumol and Tobin, s has the interpretation of the time cost of the number of trips to the bank, so \(s=\alpha \frac{x}{m},\) where \(\alpha \) is the time cost per trip, and \(\frac{x}{m}\) is the number of trips. A rather different specification is used in the more recent literature on the optimal inflation tax; for example, Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2010) assume \(s=\sigma \left( \frac{x}{m}\right) x\), where \(\sigma (.)\) is strictly increasing.

Now note that given a level c of aggregate consumption, a switch from cash to a PA as a payment instrument for variety j has a financial cost for the consumer of \(f\left( 1+\tau ^{f}\right) \), and a time saving of \(\frac{\partial s}{\partial j}=s_{x}2cj\), where here and in what follows, subscripts denote partial derivatives, so that for example \(s_{x}=\frac{\partial s}{\partial x}\). At the household optimum, because the wage is unity, both are measured in the same units, so the net cost is \(f\left( 1+\tau ^{f}\right) -s_{x}2cj\). It is immediate that the net cost of using the PA is decreasing in j, so in any period t, there will be a critical index \(j_{t}^{*}\) such that all goods \(j<j_{t}^{*}\) are bought with cash, and all goods \(j>j_{t}^{*}\) are bought with the PA. This is consistent with what is observed in practice, where cash is used for small transactions, and PAs for larger transactions.Footnote 16

So, \(x_{t},\) the volume of goods bought with cash, is

Finally, following Correia and Teles (1996) and Teles (2003), to get \(m_{t},\) we deflate nominal money holdings by the period t price level \(P_{t}\), inclusive of the consumption tax\(\tau _t^c\) i.e.

This captures the idea that nominal money balances are needed to pay for goods where the price includes the tax \(\tau _{t}^{c}\).

In each period, the household consumes goods and leisure, and can accumulate bonds, cash, or deposits in the PA. So, the per period budget constraint is

Note that \(\left( 1-j_{t}^{*}\right) f\left( 1+\tau _{t}^{f}\right) \) is the overall cost in consumption units of using a PA for varieties \(j\ge j_{t}^{*}.\) Here, labor supply \(h_{t}\) to the intermediate good sector is the time endowment minus leisure and the time transactions cost i.e.,

Also, here, \(D_{t}\), \(B_{t}^{H}\) are holdings of deposits and bonds at time t. Finally, following Chari et al. (1996), we assume that \(M_{0}=D_{0}=B_{0}^{H}=0;\) if these initial conditions do not hold, then the government’s problem is trivial.Footnote 17

3.4 Government

The government chooses a sequences of expenditures, taxes, and nominal interest rates \(\left\{ g_{t},\tau _{t}^{c},\tau _{t}^{f},i_{t}\right\} _{t=1}^{\infty }\) to maximize the utility of the representative household (1), subject to the government budget constraint and optimization decisions by households, firms, and banks. Implicit in the choice of the nominal interest rate is a choice of ad valorem tax on real money balances. Moreover, to ensure that the choice between cash and a PA is not trivial, we assume that cash has a real resource cost, as in Correia and Teles (1996). If fiat money were free, the optimal tax on real money balances is zero, and then the household would not use a PA.Footnote 18 Specifically, we assume that there is a strictly positive per unit resource cost of real money balances, \(\gamma >0\). As we show below, the price facing the household for the use of real money balances is \(i_{t}\left( 1+\tau _{t}^{c}\right) \). The cost to the government of providing a unit of real money balances is \(\gamma \). So, the implicit ad valorem tax \(\tau _{t}^{m}\) on real money balances is defined by the identity \(i_{t}\left( 1+\tau _{t}^{c}\right) =\gamma (1+\tau _{t}^{m})\). So, effectively, the government sets a tax on real money balances as follows:

Note that because \(i_{t}\) is also a government policy instrument, \(\tau _{t}^{m}\) and \(\tau _{t}^{c}\) are set separately.

Also note that given all the other tax instruments, a wage income tax is redundant for the government. This is because as is well-known in public finance, a wage income tax is equivalent to uniform consumption tax on all goods (Atkinson and Stiglitz 2015, p309), and here, we effectively only have one good, as all varieties are consumed in fixed proportions. Unlike many papers, which drop a consumption tax to eliminate the redundancy (e.g. Atkeson et al. 1999), we retain the consumption tax because we want to be able to compare the consumption tax to the tax on fees.

As is standard in the literature, we solve the government’s tax design problem using the primal approach, as described in more detail in Sect. 5 below. In this approach, we allow the government to choose all the variables \(\{l_{t},c_{t},m_{t},j_{t}^{*}\}_{t=1}^{\infty }\) to maximize household utility subject to aggregate resource implementation constraints; the latter ensures that government choices can be decentralized. Once we have characterized the solution to this problem, we can “back out” the time path for the government’s actual policy variables i.e. the taxes on fees and consumption, \(\tau _{t}^{f},\tau _{t}^{c}\) and the nominal interest rate \(i_{t}.\)

3.5 Discussion

Our model is closely related to Freeman and Kydland (2000), and also Henriksen and Kydland (2010) and Lucas and Nicolini (2015), which build on the original Freeman-Kydland model. These models are, however, somewhat more complex as they are designed to be calibrated to macroeconomic aggregates. The model of Freeman and Kydland (2000) is used to explain certain correlations in the data, such as the positive correlation of Ml and the deposit-to-currency ratio with real output.Footnote 19 The model of Henriksen and Kydland (2010) does analyze quantitatively the welfare cost of inflation and compares it to the welfare cost of a labor tax, and so it is closer in spirit to what we do here, but it does not analyze the optimal tax problem analytically.

In more detail, start from the model of Henriksen and Kydland (2010). Then, if we drop capital as a factor of production, introduce government bonds as a store of value, and set the reserve ratio for the banking system equal to zero, we arrive at a model that is very close to the one of this paper. We think that these simplifications are appropriate because our objective is to characterize optimal taxes, not explain macroeconomic aggregates.

However, a major difference is that we model transactions costs somewhat differently. In Henriksen and Kydland (2010), the transactions cost s is interpreted as the number of trips the household makes to the asset market, or a savings account. On each trip, the household can sell capital and thus replenish its stocks of both fiat money and deposits. This seems to us a somewhat old-fashioned way of thinking about time transactions costs. As already mentioned, a key feature of electronic banking is that the time cost of moving money from (say) a savings account to the PA is very low and we in fact set that cost to zero. Rather, s in our model is the cost of obtaining and managing cash e.g. trips to ATMs, guarding against theft, etc.

Finally, if we assume that only fiat money can be used for purchases, i.e. if we impose \(j^{*}\equiv 1\), our model reduces to the model of Correia and Teles (1996) or Teles (2003). So, our results can be interpreted as generalizations of theirs.

4 Household behavior

In this section, we characterize household behavior, given a fixed sequence of taxes and government expenditures. We can write (4) in real terms as

where \(\pi _{t+1}=\frac{P_{t+1}}{P_{t}}-1\) is the rate of inflation. Substituting out \(d_{t}+b{}_{t}^{H}\ \)in (7), and using (5), we obtain the present-value budget constraint:

where \(\chi _{t}=\prod \nolimits _{j=1}^{t}\frac{1}{R_{t}}\), and \(R_{t}=\frac{1+i_{t}}{1+\pi _{t}}.\) We can make two remarks at this point,. First, as deposits are perfect substitutes for bonds, the choice of \(d_{t}\) by the household is indeterminate. Second, as is standard, the opportunity cost of holding real money balances is the nominal interest forgone i.e. \(i_{t}\); the complication here is that the opportunity cost is also scaled by \(1+\tau _{t}^{c}\) because one unit of consumption costs \(1+\tau _{t}^{c}\) from (7).

The household then maximizes (1) subject to (8). To write the first-order conditions compactly, we will use the notation \(u_{ct}\) for the derivative of \(u(c_{t},l_{t})\) with respect to \(c_{t}\), with second and cross-derivatives being denoted \(u_{cct},u_{clt}\) and so on.Footnote 20 Using this notation, we can write the first-order conditions for choice of \(c_{t},l_{t},m_{t},j_{t}^{*}\) respectively as:

where \(\lambda \) is the multiplier on (8) and where it is understood that \(s_{xt}\) is the derivative with respect to \(x_{t}=\left( j_{t}^{*}\right) ^{2}c_{t}\) from (3). Note from (11), the household holds real money balances up to the point where the cost, \(i_{t}\left( 1+\tau _{t}^{c}\right) \), is equal to the marginal reduction in transactions time, \(-s_{mt}.\) So, as Teles (2003) observes, the true cost of money to the household is not \(i_{t}\), but \(i_{t}\left( 1+\tau _{t}^{c}\right) \), reflecting the fact that money is implicitly subject to the consumption tax, because of the need to use money to pay the consumption tax. Similarly, (12) says that the household uses payment services up to the point where the per transaction cost of doing so, \(f\left( 1+\tau _{t}^{f}\right) \), is equal to time transaction cost saving \(s_{xt}2c_{t}j_{t}^{*}\).

Finally, a note on the second-order conditions. Given strict quasi-concavity of the utility function in \(c_{t},l_{t}\), and by inspection of (8), we just need \(s\left( \left( j^{*}\right) ^{2}c,m\right) \) to be convex in c, m, and \(j^{*}\). It is tedious but straightforward to check that sufficient conditions for this are simply that s is convex in its arguments x, m.Footnote 21

5 The tax design problem for the government

As already remarked, we solve the government’s tax design problem using the primal approach. In this approach, we allow the government to choose the quantity variables \(\left\{ l_{t},c_{t},m_{t},j_{t}^{*}\right\} _{t=1}^{\infty }\) to maximize household utility (1) subject to the resource constraint and the implementation constraint, which ensures that government choices can be decentralized. Once we have characterized the solution to this problem, we can “back out” the time path for the government’s actual policy variables i.e. the taxes on fees, real money balances, and consumption, \(\left\{ \tau _{t}^{f},\tau _{t}^{m},\tau _{t}^{c}\right\} _{t=1}^{\infty }\).

The resource constraint simply says that the output of the intermediate good, \(1-l_{t}-s_{t}\), is no smaller than the demand for that good. Following Correia and Teles (1996), we assume that in each period, there is an exogenous level of public good provision \(g_{t}\). The intermediate good also produces the final consumption good \(c_{t}\), and must also cover the real resource cost the banking system,\(\left( 1-j_{t}^{*}\right) f\), and of real money balances, \(\gamma m_{t}\). So, the resource constraint can be written as

The implementation constraint is obtained by substituting the household first-order conditions into the present value budget constraint. Substituting (9), (12) into (8), and rearranging, we get (see “Appendix”):

This derivation shows that (14) is necessary for an allocation \(\left\{ c_{t},l_{t},m_{t},j_{t}^{*}\right\} _{t=0}^{\infty }\) to be decentralizable; following standard arguments in the literature, it is also possible to prove that (14) is sufficient.

To interpret (14), we can rewrite the implementation constraint more compactly as,

where

Now, the key observation is that (15) is the implementation constraint of a standard dynamic tax problem where \(e_{t}\) is an endowment of time in periodt. So, we will refer to \(e_{t}\) as the virtual time endowment, and note that it is generally affected by choices of \(c_{t},m_{t},j_{t}^{*}\). Note also that \(m_{t},j_{t}^{*}\) only enter the tax design problem via \(e_{t}\) and the resource constraint. We assume from now on that s is homogeneous of degree k in x, m, and so by Euler’s theorem, we can write,Footnote 22

As is standard in the primal approach to tax design, we can incorporate the implementability constraint (15) into the government’s maximand by writing an effective objective for the government of

where \(\mu \) is the Lagrange multiplier on (15).

So, to summarize, the tax design problem for the government is the choice of \(\left\{ c_{t},l_{t},m_{t},j_{t}^{*}\right\} _{t=0}^{\infty }\) to maximize \(\sum _{t=0}^{\infty }\beta ^{t}W_{t}\) subject to (13), the usual non-negativity constraints on \(\left\{ c_{t},l_{t},m_{t},s_{t}\right\} ,\) and also that \(j_{t}^{*}\in \left[ 0,1\right] \). We assume that the non-negativity constraints are non-binding, but we will be interested also in the case where \(j_{t}^{*}=1\) i.e. where only cash is used, as this relates to the existing literature.

6 Results

6.1 First-order conditions for the government’s problem

First, we write down the first-order conditions for the government’s tax design problem. Assuming \(0<j_{t}^{*}<1\) at the optimum, the first-order conditions are the following:

where \(\beta ^{t}\xi _{t}\) is the Lagrange multiplier on the period t resource constraint.Footnote 23 Here, \(e_{jt}\) denotes the derivative of \(e_{t}\) with respect to \(j_{t}^{*}\), and \(e_{mt}\) denotes the derivative of \(e_{t}\) with respect to \(m_{t}\). In what follows, we will assume that the multiplier on the implementability constraint is strictly positive i.e. \(\mu >0\). To see the economic meaning of this, note first that

Note that in calculating (23), we use the fact that \(e_{t}\) is independent of \(l_{t}\). Then, combining (20) and (23), we get, after some manipulation:

Here, \(\frac{\xi _{t}-u_{lt}}{\xi _{t}}\) is the value of one unit of labor to the government, relative to its value to the household, and thus measures the social gain from additional taxation at the margin. We will assume that this is positive; if it is negative or zero, there is no need for distortionary taxation. Also, as \(u_{clt}\ge 0\) is assumed, \(1+H_{lt}\ge 0\) as long as \(e_{t}\ge l_{t}\). But from (17), \(e_{t}\ge l_{t}\) as long as s is not “too large”. Given that estimated transactions costs in practice are a very small share of total available time (see Sect. 7 below), this seems a reasonable assumption to make.

6.2 Optimal payment service taxes

The first-order conditions for the government’s tax design problem can be combined with the household’s first-order conditions to “back out” intuitive formulae for the optimal taxes. This Proposition is proved in the “Appendix”.

Proposition 1

If \(0<j_{t}^{*}<1\) at the optimum, then the optimal payment service taxes are

where \(Z=\frac{\mu u_{lt}}{\xi _{t}}>0\).

So, we see that both taxes take a similar form; there is a term in \(1-k\), where k is the returns to scale in the transactions cost function, and then a term in the elasticity of the marginal time transactions cost of additional cash purchases with respect to x, \(\varepsilon _{xt}\) (for fees), or with respect to m, \(\varepsilon _{mt}\) (for cash). In particular, the taxes are both decreasing in k and increasing in the elasticities.

We can develop some intuition for this as follows. The general principle is that the household has a virtual time endowment \(e_{t}\), which is untaxable directly. But, it is taxable indirectly via choice of payment services taxes. Thus, a tax will be positive if it indirectly reduces the virtual time endowment via its impact on household choices of \(m_{t},j_{t}^{*}\). Thus, in general terms, the intuition is similar to that of Corlett and Hague (1953), that taxes should be set to indirectly tax untaxable leisure. However, the specific mechanisms are quite different; in Corlett and Hague, the key variable is the degree of complementarity in preferences between leisure and the taxed goods. Here, it is the properties of the transactions technology that are key.

Specifically, consider first an increase in \(\tau _{t}^{m}\). This will decrease the use of cash balances m by the household. In turn, by inspection of (17), this decrease in m has two effects on \(e_{t}\). First, as s is decreasing in m, an increase \(\tau _{t}^{m}\) decreases the virtual labor endowment if \(k<1\). In this case, the tax will be positive. This explains the term in \(1-k\) in (26). A second effect is that as \(s_{xm}<0\), the decrease in m increases \(s_{x}\) and thus reduces \(e_{t}\). This explains the second positive term in \(\varepsilon _{mt}\) in (26).

Next, consider an increase in \(\tau _{t}^{f}\). This will decrease the use of the PA by the households i.e. increase \(j^{*}\), which raises x. In turn, by inspection of (17), this increase in x has three effects on \(e_{t}\). First, as s is increasing in x, an increase \(\tau _{t}^{f}\) decreases the virtual labor endowment if \(k<1\). In this case, the tax will be positive. This explains the term in \(1-k\) in (25). A second effect is that as \(s_{xx}>0\), the increase in x increases \(s_{x}\) and thus reduces \(e_{t}\). This explains the positive term in \(\varepsilon _{xt}\) in (25). A final effect is that an increase in \(j^{*}\)has an ambiguous effect on \(j_{t}^{*}\left( 1-j_{t}^{*}\right) \), and thus \(e_{t},\) in (17); it increases (decreases) it if \(j_{t}^{*}<0.5\) (\(j_{t}^{*}>0.5\)). This explains the middle term in (25).

What can we say about the signs and relative sizes of the taxes? Note first from (26) that as long as \(k\le 1\), \(\tau _{t}^{m}>0\) i.e. the inflation tax is positive. But, we cannot be sure that the tax on fees will be positive, due to the second term \(\frac{1-2j_{t}^{*}}{j_{t}^{*}}\) which can be negative, and indeed, we will shortly see that this is a possibility.

To get further results on the relative size of the payment taxes, we assume the special case where \(s=\alpha \frac{x^{k+1}}{m}\). If \(k=0\), this is the Baumol-Tobin specification of s. If \(k=1\), it is a special case of Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2010) specification \(\sigma \left( \frac{x}{m}\right) x\). With this specification of s, it is easily calculated that \(\varepsilon _{xt}=k,\;\varepsilon _{mt}=k+1\) and as a consequence, we can show:

Proposition 2

If \(0<j_{t}^{*}<1\) at the optimum, and \(s=\alpha \frac{x^{k+1}}{m}\), then \(\tau _{t}^{f}<\tau _{t}^{m}\) i.e. fees should be taxed at a lower rate than cash. Also, \(\tau _{t}^{f}>0\) iff \(j_{t}^{*}<\frac{1+2k}{1+3k}\), and \(\tau _{t}^{m}>0\) iff \(j_{t}^{*}<\frac{2+2k}{1+3k}\).

So, we see that in this special case, both taxes are positive if the fraction of goods purchased with cash, \(j_{t}^{*}\), is small relative to k. For particular values of k, we can say more. In the Baumol–Tobin case, where \(k=0,\) we see immediately that we always have \(\tau _{t}^{m},\tau _{t}^{f}>0\), irrespective of \(j_{t}^{*}\). If \(k=1\), then the condition for \(\tau _{t}^{m}>0\) always holds, and \(\tau _{t}^{f}>0\) if and only if \(j_{t}^{*}<\frac{3}{4}\), but if \(j_{t}^{*}>\frac{3}{4}\), fees should be subsidized. The conditions for non-negative taxes of course follow fairly directly from (25), (26) as k appears negatively in both (25), (26), and \(j_{t}^{*}\) appears positively in (26) and also in (25) if \(j_{t}^{*}<0.5\).

We conclude by linking our results to two important existing literatures on optimal tax. The first is the classic Diamond and Mirrlees (1971) result on production efficiency. To proceed, note that in our model, there is a special kind of household production technology, where aggregate consumption c is “produced” from purchases of individual varieties c(i) plus a time input s, real money balances m, and fees \(f\left( 1-j^{*}\right) \). So, following the literature on household production, it is of interest to know when there is production efficiency for the household in the Diamond–Mirrlees sense, i.e. when inputs to aggregate consumption are untaxed. As the time input s is untaxable by definition, production efficiency requires that the taxes on money and fees will be zero. But, from Proposition 2, we see that as long as \(k\le 1\), \(\tau _{t}^{m}>0\) i.e. the inflation tax is positive. So, we can state:

Proposition 3

If \(0<j_{t}^{*}<1\) at the optimum, then there is never production efficiency for the household i.e. the use of cash and PAs is always distorted by the tax system if \(k\le 1\).

We can make two observations at this point. First, the Diamond–Mirrlees result says that a sufficient condition for production efficiency is constant returns to scale in production. Here, the analogous assumption, i.e. constant returns in s(x, m) i.e. \(k=1\) is not sufficient. For example, from (26), if \(k=1,\)\(\tau _{t}^{m}=0\) additionally requires \(s_{xmt}=0\), and the latter does not hold for any of the specifications of the transactions cost function s considered in the literature. So, in this setting, the Diamond–Mirrlees result does not carry over in a simple way to household production.

Second, Proposition 3 is related to the literature on household production, which finds that the optimal tax structure should generally distort the use of inputs in household production, as we do. For example, Sandmo (1990) shows that in a simple model where the final consumption can be produced from household time and a produced input, the household input should generally be taxed. The paper by Kleven et al. (2000), which extends Sandmo’s analysis, finds similar results.

The second literature that we wish to link to is the existing literature on the optimal inflation tax. In that literature, cash is the only medium of exchange, so we assume that at the optimum, \(j_{t}^{*}=1.\) This might be because the cost of money \(\gamma \) is very low. In this case, from (26), we see

In such a case, the tax on real money balances is entirely determined by the returns in the time transaction demand function s. This is exactly the result in Correia and Teles (1996) and Teles (2003). As Teles (2003) remarks, ”if the transactions technology is constant returns to scale, so that \(k=1\), the modified Friedman rule is optimal. If \(k>1\), money should be subsidized, and if \(k<1\), money should be taxed.” So, we see that our results nest Correia and Teles (1996) as a special case. Also, comparing Proposition 2 to their result, we see that when the household has a choice of transactions technologies, compared to the Corriea-Teles formula, real money balances will be taxed more heavily. This is because increasing money balances have an additional positive effect on the virtual time endowment \(e_{t}\) via \(s_{x}\) when \(j_{t}^{*}<1\). In other words, their simple characterization of \(\tau _{t}^{m}\) in (27) is not robust to alternative forms of payment.

6.3 The consumption tax

We now turn to the optimal tax on consumption. We have the following characterization of the optimal consumption tax in ad valorem form, as a fraction of the total price of consumption, inclusive of both tax and time transactions costs:

Proposition 4

The optimal consumption tax as a fraction of the tax-inclusive price of consumption is

where \(H_{ct}=\frac{1}{u_{ct}}\left( u_{cct}c_{t}-u_{clt}\left( e_{t}-l_{t}\right) -u_{lt}e_{ct}\right) \) and \(H_{lt}\) is defined in (24).

This is proved in the “Appendix”. This formula is in fact very close to the formula for the optimal consumption tax in the usual static case without a transactions technology, when the primal approach is used (Atkinson and Stiglitz 2015). The term of the left-hand side of the formula is the consumption tax expressed as a fraction of the marginal rate of substitution between consumption and leisure. This can be seen by dividing Eq. (9) by (10), giving the marginal rate of substitution equal to \(1+\tau _{t}^{c}+\left( j_{t}^{*}\right) ^{2}s_{xt}\). This differs from the standard formula due to the inclusion of the term \(\left( j_{t}^{*}\right) ^{2}s_{xt}\), which is the additional time transactions cost associated with an additional unit of consumption. On the right-hand side, as already remarked, \(\frac{\xi _{t}-u_{lt}}{\xi _{t}}\) is the value of one unit of labor to the government, relative to its value to the household, and thus measures the social gain from additional taxation at the margin. Second, by inspection, \(-H_{ct}\) measures the degree of complementarity between consumption and leisure; the higher this is, other things equal, the higher the total effective tax on consumption, a well-known result. Note that if there are no transactions costs, i.e. \(e_{t}\equiv 1\), then \(H_{ct}\) reduces to the standard formula found in the primal approach to the static tax design problem (Atkinson and Stiglitz 2015).Footnote 24

One might ask why in our dynamic setting, the consumption tax formula is qualitatively identical to the static case. The reason is the following. In our dynamic model, the government controls the marginal rate of substitution between present and future consumption by the choice of the nominal return on the savings instrument i.e. bonds, of \(i_{t}\). This leaves the consumption tax as the instrument to control the marginal rate of substitution within the period between consumption and leisure, as in the static case. As a result, the formula for the optimal consumption tax in (28) is virtually identical to the static case (conditional on the complications due to costly transactions, captured by the term \(\left( j_{t}^{*}\right) ^{2}s_{xt}\)).

Finally, we can compare \(\tau _{t}^{c}\) to the tax on fees. Using (24) to substitute out for \(\mu \), in (A.8), we get:

So, comparing (28) and (29), we see that there is no obvious link between \(\tau _{t}^{c},\tau _{t}^{f}\) ; the ratio of the two depends on k and \(\varepsilon _{xt}\), as well as \(H_{lt}-H_{ct}.\) To investigate further, we turn to numerical simulations.

7 A calibrated model

To showcase the main theoretical results, we use a calibrated version of the model to numerically solve for the optimal value of the three endogenously determined taxes, \(\tau _{t}^{f},\tau _{t}^{c},\tau _{t}^{m}\). The aim is to provide a sense of the relative sizes of taxes, and how results would vary with key exogenous parameters such as the returns to scale in the time transactions cost function, k, and the cost of using the PA, f. These parameters are particularly important for the following reasons. First, we already know that k plays an important role in determining the optimal inflation tax. Furthermore, analytically, we have shown that when k is small (at zero or close to it), \(\tau ^{f}\) should be positive. Second, empirically, technological innovation is driving f lower over time, and we would like to know how this could affect payment service taxes.

In this illustration, we assume that the exogenous expenditure requirement \(g_{t}\) is constant over time at g, in which case the economy converges immediately to a steady state. We use a standard iso-elastic functional form for utility in (1) of the form:

In addition, we also assume the same functional form for s as in Proposition 2 i.e.

Here, k measures returns to scale, as above. Special cases include \(k=0\), which is the Baumol-Tobin case, and \(k=1,\)which is the specification of Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2010).

Using (30), (31), all the equilibrium conditions of the model, plus the first-order conditions to the government’s optimal tax problem, can be written in a simplified form at the steady state. The details are given in the Online Supplementary “Appendix”. In particular, the equilibrium conditions can be written as a number of simultaneous equations in unknowns \(\left( c,l,m,j^{*},\lambda ,\tau ^{c},\tau ^{m},\tau ^{f},Z\right) \) as described in the Online Supplementary Appendix. As defined in Proposition 1, \(Z=\frac{\mu u_{l}}{\xi }\) is the value of one unit of labor to the government, relative to its value to the household, and thus the social gain from additional taxation at the margin.

Table 1 summarizes the calibrated parameters. First, \(\theta ,\eta \) are the utility function parameters, and have the interpretation of the inverses of the inter-temporal elasticity of substitution of consumption and leisure, respectively. There are a very large range of estimates of \(\theta ,\) ranging from an early empirical study, Hall (1988), which concludes that it is not likely to be larger than 10, to more recent studies which give values of \(\theta \) of around 1 (Vissing-Jørgensen and Attanasio 2003; Gruber 2013). Given this range, we take a central value of 1. Early empirical studies find \(\eta \) to be greater than 1 (Mankiw et al. 1985), while more recent studies (Smets and Wouters 2007, 2005) find \(\eta \) to be near 2, and we therefore set \(\eta =2\).

Next, A, g are set to yield a plausible ratio of government expenditure to output of around 0.3.Footnote 25 Then, \(\alpha \) is set to target a realistic value for s. Based on a recent study of transactions costs, we assume that the household spends around 10 hours a year managing cash (Mazzotta and Chakravorti 2014). This includes time spent visiting ATMs, etc. This gives a target value for s of 10 divided by total number of hours in the year, i.e. \(16\times 365=5840\), which gives \(s=0.17\%\). Next, our central value of f is set at 0.015, based on Philippon (2015) and Bazot (2018), who calculate that the costs of financial intermediation for the banking sector in the US and Europe are around 2.5–3% of assets intermediated.Footnote 26 Finally, \(\gamma \) is set to ensure that the share of transactions that are cash, measured by \(j^{*}\), is around 50%, a reasonable figure for the US and Europe.Footnote 27 Finally, k, the degree of homogeneity of s, is chosen to range between 0 and 1, which covers all the usual specifications in the literature.

Before we turn to numerical simulations of the optimal taxes, we perform a simple comparative statics exercise to understand how key endogenous variables \((j^{*},m,c,l)\) respond the changes in exogenous taxes \((\tau ^{f},\tau ^{m})\), varying \(\tau ^{c}\) residually to satisfy the government budget constraint. The details are reported in the Online Appendix Section C. They show that as expected, \((j^{*},m)\) rise as PAs are more heavily taxed, and fall as cash in more heavily taxed. Other variables are not not very sensitive to the payment service taxes.

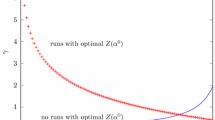

Now we turn to our main results. Figures 1 and 2 show how the optimal taxes \(\tau ^{c},\tau ^{m},\tau ^{f}\) change as the key parameters k, f change. Note that \(\tau ^{c},\tau ^{m},\tau ^{f}\) are all of the same order of magnitude, and the implied interest rate i, from the relationship (6), takes a sensible rate of values between 1 and 3% (not reported here).

In Fig. 1, k varies between 0 and 1, while f is fixed. This figure shows that first, both \(\tau ^{m},\tau ^{f}\) decrease markedly as the returns to scale in transactions costs increase, though \(\tau ^{m}\) remains positive at \(k=1\). Also, we see that \(\tau ^{m}\) is consistently bigger than \(\tau ^{m}\) , consistent with Proposition 1. We also see that for k above 0.5 or so, \(\tau ^{f}\) becomes a subsidy, a possibility that was shown theoretically in the previous section. We also see that real money balances should be taxed, \(\tau ^{m}>0\), even when \(k=1\). This is consistent with our theoretical finding in the previous section that the Correia-Teles result is not robust to alternative forms of payment. Finally, we see that both taxes are never zero at once, meaning that the use of cash and PAs is always distorted by the tax system, consistently with Proposition 3.

In Fig. 2, f varies between 0.01 and 0.02. This figure shows that both \(\tau ^{m},\tau ^{f}\) decrease markedly as the fee to scale in transactions costs increase, though \(\tau ^{m}\) remains positive at \(k=1\). This figure is again consistent with our theoretical results. For example, we see that \(\tau ^{m}\) is consistently bigger than \(\tau ^{m}\) , consistent with Proposition 1. We also see that for f above 0.015 or so, \(\tau ^{f}\) becomes a subsidy, a possibility that was shown theoretically in the previous section. One intuition for why \(\tau ^{f}\) can be negative can be gleaned from (A.3). As f rises, \(j_{t}^{*}\) increases i.e. cash is used more, and this tends to make the effect of \(j_{t}^{*}\) on the virtual leisure endowment, \(e_{jt}\) positive. So, in order to indirectly tax this virtual leisure endowment, \(j_{t}^{*}\) should be reduced, which can be achieved by subsidizing PAs.

8 Conclusions

This paper has considered the optimal taxation of payment services, when realistically, the household can use either cash and or a bank account with services, such as debit cards, for the purchase of different varieties of goods. The setting is an extension of Correia and Teles (1996), to allow for the use of bank accounts as a form of payment, as in Freeman and Kydland (2000). Our first contribution is to develop simple formulae for the optimal ad valorem taxes on both real money balances and payment fees. For common specifications of the time transaction cost function, we can show that the tax on real money balances is always greater than the tax on fees, and also, while the former is always positive, the tax on fees may be negative.

Numerical results, using a calibrated version of the model, yielded additional insights. We found that both the inflation tax and the tax on fees decrease markedly as the returns to scale in transactions costs increase from zero to one. The results show also that both the inflation tax and the tax on fees increase as the bank fee decreases; this is interesting as the move away from cash is ultimately driven by technological innovation that reduces fees. Moreover, when the fee is large, the fee tax can be negative, i.e. bank fees should be subsidized. We also find that the tax on bank fees, can be greater or less than the rate of consumption tax, although both taxes are of the same order of magnitude. So, our results show fairly robustly that this part of banking sector activity should probably not be left untaxed.

Notes

See for example, Correia and Teles (1996, 1999) which consider a transactions cost theory of money demand, or Chari et al. (1991, 1996), where some goods can be bought on costless credit. More recent models include a more micro-founded search theoretic demand for fiat money e.g. Aruoba and Chugh (2010), but existing models of this type do not include a banking sector. The literature is surveyed in Kocherlakota (2005) and Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2010).

As a result of these trends, the provision of payment services is an increasing source of both activity and profit for banks and payment network operators, such as VISA and Mastercard. For example, in the United States, the fee averages approximately 2% of transaction value. This is giving rise to large and growing revenues and profits for both banks and the operators. For example, DeYoung and Rice (2004) estimate that in the US in 2003, non-interest income accounted for half of all bank income, and 52% of non-interest income was generated by fees associated with payment accounts. Visa, the largest payment network operator, had gross income and profit of $18.36 bln. and $11.69 bln. in the 2017 financial year.

The countries were Austria, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, The Netherlands, USA.

On average, in the EU, consumption is about 70% of GDP. Also, as a rough approximation, about 50% of total transactions are non-cash. So, the percentage is 1%/\((0.7\times 0.5)\)=2.8%.

So, a payment account is what is known as a checking account in the USA, and a current account in the UK.

These fees are known as merchant discount fees. The bulk of this is made up of a change for card use by the card-issuing bank, known as the interchange fee, and the reminder of the merchant discount fee goes to the card company and the acquiring bank.

This is discussed formally in Sect. 3.4.

The Correia-Teles model is a special case of ours, as explained in Sect. 3.5

The work of Correia and Teles (1996) has already shown, however, that in an environment where only cash is used for transactions, such an efficiency result (i.e. a zero inflation tax) requires the additional condition that the transactions technology for cash must be constant returns to scale. The intuition is that if (say) the transactions technology is decreasing returns, this creates a ”virtual profit” for the household which can be taxed via a positive inflation tax. This is, of course, analogous to the original Diamond–Mirrlees result, which states that inputs to production should be untaxed as long as there are constant returns to scale (or 100% profit taxation), but taxed if there are decreasing returns to scale (Stiglitz and Dasgupta 1971).

See also the recent IMF proposals for a Financial Activities Tax levied on bank profits and remuneration, one version of which - FAT1 - would work very much like a VAT (IMF 2010).

Chia and Whalley (1999), using a computational approach, reach the rather different conclusion that no intermediation services should be taxed, but their model is not directly comparable to these others, as the intermediation costs are assumed to be proportional to the price of the goods being transacted.

In particular, they show that if there is initially a wage income tax at rate \(\tau ,\) which is replaced by a consumption tax at equivalent rate \(\tau /(1-\tau ),\) then the real equilibrium is left unchanged if and only if payment services are also taxed at this equivalent rate.

In practice, the bank interchange fee is a fixed charge f, plus a percentage of the value of the transaction. For example, in the US, Visa currently charges either $0.15 plus 0.80% or $0.21 plus 0.05% for debit card retail transactions, depending on whether the bank is exempt (small) or regulated (large, over $10 billion in assets). This second percentage cost element could be introduced without changing any of the qualitative results.

For example, using a sample of Dutch retailers, ten Raa and Shestalova (2004) estimate that the point at which households switch from cash to electronic payment media is somewhere between 13 and 30 Euros. More recently Wang and Wolman (2016) find similar switching thresholds for a large data-set for the US.

As is well-known, if the initial stock \(M_{0}+D_{0}+B_{0}^{H}\) of nominal assets is positive (negative), then welfare is maximized by setting the initial price level to infinity (or sufficiently low). See Chari et al. (1996, p207).

A formal proof of this point is as follows. Assume for convenience following Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2010), that \(s=\sigma \left( \frac{c}{m}\right) c\), and that there is a finite value of velocity \(v=\frac{c}{m}\), \(\bar{v}\) such that the household is satiated i.e. \(\sigma '\left( \bar{v}\right) =0\). Then, if real balances are untaxed, from (11) below, the household will use real money balances up to the point where \(s_{mt}=0\) or \(m_{t}=\bar{v}c_{t}\), which in turn implies from (A.6) below, that \(e_{mt}=0\) as long as \(j_{t}^{*}=1\). But, if \(e_{mt}=\gamma =0,\) then from (21) below, it is optimal to have \(s_{mt}=0\), completing the argument.

So, the “t” denotes the time at which the derivative is taken, not the derivative with respect to t, which of course is not even defined, as time is discrete.

This is satisfied in the Baumol-Tobin case, for example as \(s_{xx}=0,\ s_{mm}=\frac{\alpha x}{m^{3}}>0,\ s_{mx}=-\frac{\alpha }{m^{2}},\) which implies \(s_{xx}s_{mm}\le \left( s_{mx}\right) ^{2}.\)

Specifically, \(x_{t}s_{xt}+m_{t}s_{mt}=ks_{t}.\)

This specification of the Lagrange multiplier just ensures that \(\xi _{t}\) is time-invariant in the steady state and is thus just made to simplify the presentation.

One might also ask how our result relates to the well-known Ramsey tax rules in static optimal tax theory. The connection is as follows. First, in the special case where u is quasi-linear, i.e. \(u(c,l)=u(c)+l\), \(H_{lt}=0\) and \(H_{ct}=\frac{1}{u_{ct}}\left( u_{cct}c_{t}-e_{ct}\right) \). If we assume furthermore that there are no transactions costs, \(e_{t}=1\) and so \(e_{ct}=0\). Then, \(-H_{ct}=-\frac{u_{cct}c_{t}}{u_{ct}}\) is just one over the elasticity of demand for the consumption good, so (28) reduces just to the classic Ramsey inverse elasticity rule.

Output is \(y=1-l-s\).

The precise calculation is as follows. The real value of consumption purchased using PAs is \(c\left( 1-\left( j^{*}\right) ^{2}\right) \), and the real value of resources used in payments is \(f\left( 1-j^{*}\right) .\) So, in the model, the cost of bank payment services as a share of consumption is \(\frac{f\left( 1-j^{*}\right) }{c\left( 1-\left( j^{*}\right) ^{2}\right) }=\frac{f}{c\left( 1+j^{*}\right) }.\) From Schmiedel et al. (2012), and the discussion in the introduction, we estimate this to be to be about 3%. So, we set \(\frac{f}{c\left( 1+j^{*}\right) }=0.03.\) In our model, which calibrated to a consumption to GDP ratio of 0.7, \(c=0.25\) on average, and also also \(j^{*}\) is calibrated to 0.5. Substituting these elements into the last equation gives a value of \(f=0.011\). This turns out to give rise to computational problems, and so we choose a slightly higher central value of \(f=0.015.\)

References

Acharya VV, Pedersen LH, Philippon T, Richardson M (2017) Measuring systemic risk. Rev Financ Stud 30:2–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhw088

Aigner R, Bierbrauer F (2015) Boring banks and taxes. Working paper series of the Max Planck Institute for Research on collective goods 2015\_07, Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2603137. Accessed 20 Feb 2019

Aruoba SB, Chugh SK (2010) Optimal fiscal and monetary policy when money is essential. J Econ Theory 145(5):1618–1647

Atkeson A, Chari VV, Kehoe PJ (1999) Taxing capital income: a bad idea. Quarterly Review 2331, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/quarterly-review/taxing-capital-income-a-bad-idea

Atkinson AB, Stiglitz JE (2015) Lectures on public economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Auerbach AJ, Gordon RH (2002) Taxation of financial services under a VAt. Am Econ Rev 92(2):411–416

Bagnall J, Bounie D, Huynh K, Kosse A, Schmidt T, Schuh S (2016) Consumer cash usage: a cross-country comparison with payment diary survey data. Int J Central Bank 12(4):1–61

Bazot G (2018) Financial consumption and the cost of finance: measuring financial efficiency in Europe (1950–2007). J Eur Econ Assoc 16(1):123–160. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx008

Bianchi J, Mendoza EG (2010) Overborrowing, financial crises and ’Macro-prudential’ taxes. Working Paper 16091, National Bureau of economic research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w16091

Buettner T, Erbe K (2014) Revenue and welfare effects of financial sector VAT exemption. Int Tax Public Financ 21:1028–1050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-013-9297-5

Chari V, Christiano L, Kehoe P (1996) Optimality of the Friedman rule in economies with distorting taxes. J Monetary Econ 37(2–3):203–223

Chari VV, Christiano LJ, Kehoe PJ (1991) Optimal fiscal and monetary policy: some recent results. J Money Credit Bank 23(3):519–539

Corlett WJ, Hague DC (1953) Complementarity and the excess burden of taxation. Rev Econ Stud 21:21–30

Correia I, Teles P (1996) Is the Friedman rule optimal when money is an intermediate good? J Monetary Econ 38(2):223–244

Correia I, Teles P (1999) The optimal inflation tax. Rev Econ Dyn 2(2):325–346

De La Feria R, Lockwood B (2010) Opting for Opting-In? An evaluation of the European Commission’s Proposals for reforming VAT on financial services. Fiscal Stud 31(2):171–202

DeYoung R, Rice T (2004) How do banks make money? a variety of business strategies. Econ Perspect 28(4):52–67

Diamond P, Mirrlees J (1971) Optimal taxation and public production: I-production efficiency. Am Econ Rev 61(1):8–27

Ebrill L, Keen M, Bodin J-P, Summers V (2001) The modern VAT. International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781451993592.071

Esselink H, Hernández L (2017) The use of cash by households in the euro area. Research Report 201, ECB occasional paper. https://doi.org/10.2866/377081

Freeman S, Kydland FE (2000) Monetary aggregates and output. Am Econ Rev 90(5):1125–1135

Gruber J (2013) A tax-based estimate of the elasticity of intertemporal substitution. Q J Finance 03(01):1350001

Grubert H, Mackie J (2000) Must financial services be taxed under a consumption tax? Natl Tax J 53(1):23–40

Hall R (1988) Intertemporal substitution in consumption. J Polit Econ 96(2):339–57

Henriksen E, Kydland FE (2010) Endogenous money, inflation, and welfare. Rev Econ Dyn 13(2):470–486

IMF (2010) A fair and substantial contribution by the financial sector: final report for the G-20’. Technical report, International Monetary Fund (IMF). https://www.imf.org/external/np/g20/pdf/062710b.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2019

Jack W (2000) The treatment of financial services under a broad-based consumption tax. Natl Tax J 53(4):841–851

Jeanne O, Korinek A (2010) Managing Credit Booms and Busts: a Pigouvian taxation approach. NBER Working Paper 16377, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. https://doi.org/10.3386/w16377

Keen M (2011) The taxation and regulation of banks. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2011/wp11206.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2019

Kleven HJ, Richter W, Sørensen PB (2000) Optimal taxation with household production. Oxf Econ Papers 52(3):584–94

Kocherlakota NR (2005) Optimal monetary policy: what we know and what we don’t know. Int Econ Rev 46(2):715–729

Lucas RE, Nicolini JP (2015) On the stability of money demand. J Monetary Econ 73:48–65

Mankiw NG, Rotemberg J, Summers L (1985) Intertemporal substitution in macroeconomics. Q J Econ 100(1):225–251

Matheny W, O’Brien S, Wang C (2016) The state of cash: preliminary findings from the 2015 diary of consumer payment choice. Technical report, Cash Product Office (CPO), Federal Research System. https://www.frbsf.org/cash/publications/fed-notes/2016/november/state-of-cash-2015-diary-consumer-payment-choice. Accessed 14 Feb 2019

Mazzotta B, Chakravorti B (2014) Who pays more to use cash? J Paym Strategy Syst 8(1):94–107

Perotti E, Suarez J (2011) A Pigovian approach to liquidity regulation. Int J Central Bank 7(4):3–41

Philippon T (2015) Has the US Finance industry become less efficient? On the theory and measurement of financial intermediation. Am Econ Rev 105(4):1408–1438

Piggott J, Whalley J (2001) VAT base broadening, self supply, and the informal sector. Am Econ Rev 91(4):1084–1094

PWC (2011) How the EU VAT exemptions impact the banking sector. Technical report PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC). https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/financial-services/pdf/2011-10-18_vat_study_final_report.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2019

Sandmo A (1990) Tax distortions and household production. Oxf Econ Papers 42(1):78–90

Schmiedel H, Kostova G, Ruttenberg W (2012) The social and private costs of retail payment instruments: a European perspective. Research Report 137, ECB Occasional Paper. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecbocp137.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2019

Schmitt-Grohe S, Uribe M (2010) The optimal rate of inflation. Handb Monetary Econ 3:653

Smets F, Wouters R (2005) Comparing shocks and frictions in US and euro area business cycles: a Bayesian DSGE approach. J Appl Econ 20(2):161–183

Smets F, Wouters R (2007) Shocks and frictions in US business cycles: a Bayesian DSGE approach. Am Econ Rev 97(3):586–606

Stiglitz JE, Dasgupta P (1971) Differential taxation, public goods, and economic efficiency. Rev Econ Stud 38(2):151–174

Teles P (2003) The optimal price of money. Econ Perspect Q(II):29–39. https://ideas.repec.org/a/fip/fedhep/y2003iqiip29-39nv.27no.2.html. Accessed 14 Feb 2019

ten Raa T, Shestalova V (2004) Empirical evidence on payment media costs and switch points. J Bank Finance 28(1):203–213

Vissing-Jørgensen A, Attanasio OP (2003) Stock-market participation, intertemporal substitution, and risk-aversion. Am Econ Rev 93(2):383–391

Wang Z, Wolman AL (2016) Payment choice and currency use: Insights from two billion retail transactions. J Monetary Econ 84(Supplement C):94–115

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper is a substantially revised version of Centre for Business Taxation Working Paper 1423, ”Should transactions services be taxed at the same rate as consumption?”, published in 2014. We would like to thank Robin Boadway, Steve Bond, Clemens Fuest, Michael Devereux, Andreas Haufler, Michael McMahon, Miltos Makris, Ruud de Mooij, Carlo Perroni, and seminar participants at the University of Southampton, GREQAM, the 2010 CBT Summer Symposium, the 2011 IIPF Conference and OFS workshop on Indirect Taxes for helpful comments on earlier drafts. Ben Lockwood also gratefully acknowledges support from the ESRC grant RES-060-25-0033, ”Business, Tax and Welfare”.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Construction of the implementation constraint From (9)–(12) we have ,

So, substituting these expressions in (8), we get:

Rearranging (A.1) gives (14) as required. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 1

Combining first-order conditions (11), (21) with 6, and (12) with (22), we get general formulae for the optimal taxes:

Next, using using (A.2) and (17), we can compute \(e_{t}=\left( k-1\right) s_{t}-s_{xt}2c_{t}j_{t}^{*}\left( 1-j_{t}^{*}\right) \)

to compute \(e_{jt}\), we see that

Then, using the household optimization condition (12) to substitute out for f, we get

Finally, simplifying the right-hand side of (A.4), and using \(x_{t}=(j_{t}^{*})c_{t}\), we get

where \(Z=\frac{\mu u_{lt}}{\xi _{t}}\).

For the optimal inflation tax, the argument is similar. First, using (A.2) and (17), to compute \(e_{mt},\) we get:

Next, using the household optimization condition (11) and the definition of the inflation tax (6), we get a formula for \(\gamma \):

Then combining (A.6) and (A.7) gives

as required. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 2

If \(s=\alpha \frac{x^{k+1}}{m}\), then it is easily checked that \(\varepsilon _{xt}=k,\;\varepsilon _{mt}=k+1\), so (25) (26) become

Assume to the contrary that \(\tau _{t}^{f}\ge \tau _{t}^{m}\) . Then from (A.8), (A.9), as \(Z>0\), we see that

which rearranges to \(\frac{1-2j_{t}^{*}}{1-j_{t}^{*}}\ge 2\), which is impossible. To complete the proof, we note that the term in brackets in (A.8) is positive if \(j_{t}^{*}<\frac{2k}{1+3k}\), and the term in brackets in (A.9) is positive if \(j_{t}^{*}<\frac{1+2k}{1+3k}\). \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 4

where \(H_{lt},H_{ct}\) are defined in the paper above. And, from (9),(10):

Combining (A.10), (A.11), we get

Rearranging (A.12), we get:

Adding \(\tau _{t}^{c}\mu \left( H_{lt}-H_{ct}\right) \) to both sides, and and rearranging, we get

Using (A.13), and (24) and rearranging, we get

as required. \(\square \)

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.