Abstract

This paper contains a detailed experimental analysis of an isothermal plane turbulent impinging jet (PTIJ) for two jet widths at moderate Reynolds numbers (7200–13,500) issued on a horizontal plane at fixed relative distances equal to 22.5 and 45 jet widths. The available literature on such flows is scarce. Previous studies on plane turbulent jets mainly focused on free jets, while most studies on impinging jets focused on the heat transfer between the jet and an impingement plane, disregarding jet development. The present study focuses on isothermal PTIJs at moderate Reynolds numbers characteristic of air curtains. Flow visualisations with fluorescent dye and 2D particle image velocimetry (PIV) measurements have been performed. A comparison is made with previous studies of isothermal free turbulent jets at moderate Reynolds numbers. Mean and instantaneous velocity and vorticity, turbulence intensity, and Reynolds shear stress are analysed. The jet issued from the nozzle with higher aspect ratio shows more intensive entrainment and a faster decay of the centreline velocity compared to the jet of lower aspect ratio for the same value of jet Reynolds number. The profiles of centreline and cross-jet velocity and turbulence intensity show that the PTIJs behave as a free plane turbulent jet until 70–75% of the total jet height. Alongside the information obtained on the jet dynamics, the data will be useful for the validation of numerical simulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Plane impinging jets at moderate-to-high Reynolds numbers (i.e., turbulent jets) are used in a wide range of applications. A typical example in building engineering is an air curtain, which can be used to separate two environments in terms of heat and mass transfer, for example, in laboratories to reduce contamination hazard or in operating theatres. The separation efficiency of plane turbulent impinging jets (PTIJs) when used as an air curtain depends on a wide range of parameters. On the one hand, these include the environmental parameters such as air temperature differences and pressure differences over the air curtain. On the other hand, they include the jet parameters that influence the vortex structures in the jet and the entrainment process, such as the jet Reynolds number, the turbulence intensity, and the jet temperature relative to the ambient temperature.

The existing literature on PTIJs and air curtains can be divided into two clear categories: (1) basic studies on PTIJs and (2) application-oriented studies on air curtains, both of which can be performed experimentally and numerically [e.g., using computational fluid dynamics (CFD)]. Basic studies on PTIJs are important to gain a better basic understanding of the jet dynamics, which can then be utilised to improve their performance in applications such as air curtains.

A range of basic experimental studies on PTIJs have been published in the past decades. These studies generally analyse the structure of the jet and the behaviour of turbulent vortical structures by means of different measurement and visualisation techniques. In the following, an overview of previous experimental studies is provided, from which the objectives of the present study are derived.

An extensive body of the literature exists on the jet dynamics in the impingement region of the jet. Gardon and Akfirat (1965) applied a transducer based on the operating principle of thermocouples to investigate heat transfer at a plane subjected to a plane impinging jet. They also provided velocities and turbulence intensities along the centreline of the jet for Re = 5500 obtained by hot-wire anemometry. The focus of their work was on characterising the Nusselt numbers and pressure coefficients (measured by pressure taps) at the impingement plane for Re ranging from 450 to 28,000 and jet height-to-width ratios γ = h jet/w jet ranging from γ = 2–80, with h jet the jet height and w jet the jet width. They showed the influence of inlet jet velocity and turbulence intensity on heat transfer at the impingement plane. Gardon and Akfirat (1965) suggested that the nozzle configuration becomes less influential for jet heights larger than 8 jet widths. Korger and Krizek (1966) used naphthalene sublimation to study jet impingement for Re between 6000 and 37,800 and γ = 0.25–40. Their experiments provided values for the mass transfer coefficients at the impingement plane. The maximum mass transfer coefficients on the jet centreline occurred for jets with γ = 8–9. Cartwright and Russell (1967) employed thermocouples to analyse the evolution of the wall jet along the impingement plane and provided pressure distributions and heat transfer characteristics on the impingement plane for jets with Re between 25,000 and 110,000 and γ = 8–47. They also showed that maximum heat transfer for jets with Re ≤ 51,000 occurred at the stagnation point, while for Re > 51,000 the maximum heat transfer lied at some distance from stagnation point. They analysed existing correlations for wall jet heat transfer and assessed their applicability based on the measurement results. This analysis showed that these correlations were accurate for the developed wall jet formed after jet impingement. However, it failed to accurately predict heat transfer near the stagnation point due to the high level of turbulence in this region. They also emphasised the influence of jet turbulence on augmented heat transfer in the impingement region. Ashforth-Frost et al. (1997) used hot-wire anemometry to analyse PTIJs with Re = 20,000 and γ up to 9.2 with focus on the near-wall region. They compared the results for an unconfined configuration with a semi-confined configuration and revealed the influence of the horizontal confining plane adjacent to the jet nozzle. The results showed a decrease in entrainment and jet spreading, and an increase of the potential core length for the semi-confined configuration. Beitelmal et al. (2000, 2006) employed thermocouples to study the heat transfer in the impingement region for Re between 4000 and 12,000 and γ = 2–12. By comparing their experimental data with other studies on heat transfer at the impingement plane, they noted the importance of inlet turbulence parameters at the jet nozzle on the results. Zhou and Lee (2007) used thermocouples for PTIJ at Re ranging from 2715 to 25,005 and γ = 1–30 to analyse the influence of Re and h jet on heat transfer at the impingement plane. They showed that for situations where the impingement plane is situated beyond the potential core region, the heat transfer between the impinging jet and the impingement plane appeared to be mainly governed by the turbulence intensity.

Another group of studies examined the whole jet flow field, i.e., over the entire height of the jet. Gutmark et al. (1978) applied hot-wire anemometry at the centreline of a PTIJ at Re = 30,000 and γ = 100. They observed an influence of the impingement plane on the jet development starting at a distance of 0.75h jet from the nozzle. Yoshida et al. (1990) examined the turbulence characteristics and heat transfer of a PTIJ with Re = 10,000 using laser Doppler anemometry (LDA) and thermocouples for γ = 8. They observed a steep increase in turbulence intensity and heat transfer near the stagnation point. Guyonnaud et al. (2000) used hot-wire anemometers, pressure sensors, and smoke visualisations for an analysis of a bending PTIJ (33,000 ≤ Re ≤ 66,000, γ = 12) separating environments with different ambient pressures. The authors provided a detailed description of the physics of the jet and its general structure. Maurel and Solliec (2001) performed experiments on PTIJs with Re = 13,500 and Re = 27,000 and γ = 5–50, impinging perpendicularly on a flat plate from a variable distance. The structure of the jet was analysed by LDA along the whole jet height and by particle image velocimetry (PIV) in the impingement region. The study provided centreline velocity distributions, instantaneous velocity and vorticity fields and Reynolds stresses along the jet centreline and along vertical lines at some distance from the centreline. They concluded that the height of the impingement region constitutes 12–13% of the total jet height, regardless of Reynolds number, nozzle width or jet height. They defined velocity laws for each of the three characteristic jet regions: the potential core, with length of about 3–4 jet widths, the intermediate region and the impingement region. The study of Sakakibara et al. (2001) provided an extensive analysis of vortical structures occurring in a periodically forced impinging jet at Re = 2000 and γ = 8 using digital PIV (DPIV). The study showed the presence of ‘wall ribs’, organised vortices along the impingement plane in the lateral direction of the jet. They questioned whether these wall ribs are formed in the boundary layer close to the impingement plane or already upstream of the impingement plane. They highlighted that these wall ribs are enhanced and might be sustained by vorticity upstream of the impingement region. Moreover, the authors observed so-called ‘cross ribs’, existing only in forced impinging jets that are responsible for an increase of the intensity of wall ribs. Loubière and Pavageau (2008) investigated the vortical structures occurring in a double PTIJ formed by a splitting plate at the nozzle (Re = 20,000–140,000, γ = 10) using PIV with focus on the impingement region. They showed that these vortical structures are responsible for significant mass transfer across the jet stream. It was found that most of the vortical structures were concentrated in the impingement region, and the authors suggested that shape and size of these structures are primarily influenced by flow curvature caused by the impingement plane, and that this curvature is mainly determined by the jet height. The study by Koched et al. (2011) focused on wall ribs in the impingement region for water jets with 3000 ≤ Re ≤ 16,000 and γ = 10. They found that the length of the potential core depends on Re and reaches a maximum of three jet widths, which complies with previous studies. The impingement region height is found to be slightly dependent on Re and equal to 10 and 13% of the total jet height for Re = 3000 and Re = 16,000, respectively. The amount and size of the observed vortical structures are also slightly dependent on Re; they occur in a wide range of length scales and their shape is mainly elliptical, and the amount of clockwise vortices is proportional to the amount of counterclockwise vortices.

The aforementioned studies all highlighted the existence of vortical structures in the jet flow, their role in the dissipation of jet energy to the ambient environment, and the existence of 3D vortices in the impingement region, in which thermal energy can be exchanged between the jet and the impingement surface.

In spite of this rather large number of experimental studies on PTIJs performed in the past, there is still a scarcity of detailed and high-quality experimental data on PTIJs at moderate Reynolds numbers and a jet height larger than 10 jet widths, including an evaluation of mean and instantaneous velocity, turbulence intensity, Reynolds shear stress, and vorticity. Although Maurel and Solliec (2001) performed a similar study for a large extent of jet heights (5–50 jet widths), their experiments only provided point measurements of velocities and Reynolds stresses for Re = 13,500 and 27,000; while their PIV measurements were only conducted near the impingement region and were used to describe the vorticity field in this region. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to provide experimental data based on 2D PIV for the whole vertical centreplane of the PTIJ. The jet Reynolds number ranges from 7200 to 13,500 and two different jet widths are studied: (1) jet width of 16 mm and γ = h jet/w jet = 22.5 and (2) jet width of 8 mm and γ = 45. Both instantaneous and time-averaged results are presented. Section 2 provides a short description of the experimental set-up, Sect. 3 contains results of the flow visualisations and the results of the PIV measurements are presented in Sect. 4. Section 5 (discussion) and Sect. 6 (conclusions) conclude this paper.

2 Experimental setup

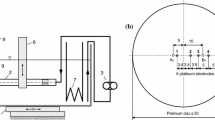

The isothermal PTIJ is generated in a water channel by issuing from a smoothly-shaped nozzle with a rectangular section upstream of the jet inlet (Fig. 1). The hydrostatic pressure driving the flow is exerted by a water column with a conditioning section consisting of one honeycomb and two screens to reduce lateral and longitudinal turbulence intensity. Water was chosen as working fluid, because it allowed to reach the moderate Reynolds numbers under study without a too large setup and the related required large field of view for the PIV measurements. The water jet is dynamically similar (equal Reynolds number) with air curtains in full scale. The streamwise inlet velocity V 0 at the end of the rectangular section downstream of the smoothly-shaped contraction and the jet width w jet at the inlet determine the jet Reynolds number (Re = V 0 w jet/ν, with ν the kinematic viscosity). In this experiment, the jet inlet velocity corresponds to jet Reynolds numbers Re = 7200–13,500. The jet is issued vertically on a horizontal plate at a distance of h jet = 360 mm. The jet width w jet is equal to 8 and 16 mm and the nozzle depth (dimension in spanwise direction) is 300 mm, resulting in nozzle aspect ratios (AR, which is the ratio of nozzle depth to width w jet) of 37.50 and 18.75, respectively. Due to the obstructing horizontal beam of the water channel, the visible part of the jet is limited to h′jet = 320 mm, with the missing part close to the jet inlet.

The following notations are used for the geometric parameters: x, y, z for the lateral, the streamwise and the spanwise (i.e. out-of-plane) directions, respectively. The flow parameters are u, v, w—the instantaneous lateral, streamwise and spanwise velocity components; U, V, W—the mean lateral, streamwise and spanwise velocity components, |v| and |V|—the instantaneous and the mean velocity magnitude, V 0—the mean jet inlet velocity; \(|{{v}_{\text{RMS}}}|(=\sqrt{u_{\text{RMS}}^{2}+v_{\text{RMS}}^{2}}/{{V}_{0}})\), u RMS , v RMS —root mean square values of the measured velocity magnitude and velocity components; ω z and Ω z —the instantaneous and the mean z-vorticity; I v and I uv—turbulence intensity based on only streamwise and both streamwise and lateral velocity fluctuations, respectively. The jet half-width δ 0.5 at a certain downstream position y (Fig. 1b) is the horizontal distance between the jet centreline and the point, where the mean streamwise velocity is equal to half the local jet mean centreline velocity V 0,y .

Prior to the PIV measurements, flow visualisations with fluorescent dye are performed to reveal the flow pattern. The dye is injected in the flow field at y = −35 mm using an injection needle with an outer diameter of 0.8 mm and a length of 80 mm, enabling injection in the centre of the jet. It is illuminated in the centreplane of the test section by a slide projector mounted below the water channel. The obtained flow patterns are recorded with a digital photo and video camera positioned perpendicular to the measurement plane.

For the PIV measurements, a 2D PIV system is used consisting of a solid-state frequency-doubled Nd:Yag laser (wavelength 532 nm and repetition rate 15 Hz) as a light source, and a charge coupled device (CCD) camera (1600 × 1200 pixels resolution, up to 30 frames/s) for image recordings. The light sheet is delivered at the bottom of the water channel by a set of mirrors and cylindrical and spherical lenses. Seeding is provided by polyamide particles (D = 50 μm, density ρ s = 1030 kg/m3) added to the water. Each measurement set consists of 5000 uncorrelated samples.

Three sets of measurements are performed, which focus on (Fig. 1a): (1) ROI1—the entire measurement plane of W × H = 192 × 360 mm2; (2) ROI2—the region close to the jet inlet (W × H = 128 × 192 mm2); and (3) ROI3—the impingement region (W × H = 128 × 176 mm2). The two latter sets provide measurement data at a higher resolution. The instantaneous PIV images are processed in five passes from 32 × 24 pixels to 16 × 12 pixels (for ROI1 and ROI2) and 48 × 32 pixels to 24 × 16 pixels (ROI3) with 50% overlap. Correlation peaks are fitted by a three-point Gauss fit algorithm advised by Forliti et al. (2000). Filters for outlier detection are applied for maximum and normalised median displacements. The correlation peak ratio is set to 1.3 to disable erroneous vectors resulting from insufficient seeding and background noise. The time separation between pulses is chosen according to the general guideline for particle displacement, which states that the particle displacement should be limited to 25% of the interrogation area (Prasad 2000).

3 Flow visualisation results

Figure 2 shows snapshots of the dye-visualised jet for Re = 7200 and w jet = 8 mm, corresponding to an inlet velocity V 0 of 0.9 m/s. The image indicates a growing shear layer and spreading of the jet after injection into the ambient fluid starting at a certain distance from the jet inlet. The indistinct jet boundaries exhibit turbulent behaviour with spanwise vortices developing in the outer region of the jet (Fig. 2a). The visualisation also indicates jet flapping as the jet is moving from side-to-side in the region close to the impingement plane: at time T 1, the jet is perpendicular to the impingement plane (Fig. 2a), however, 2 s later at T 2 it is slightly bent to the left (Fig. 2b), and 4 s later at T 4, it is bent to the right (Fig. 2d). At time T 6 (Fig. 2f), the jet again impinges perpendicularly on the surface. The jet flapping was also reported and analysed in earlier studies, such as Goldschmidt and Bradshaw (1973) and Antonia et al. (1983). It plays an important role in heat transfer between the jet and the impingement plane (e.g., Camci and Herr 2002; Chiriac and Ortega 2002; Varieras et al. 2007).

4 PIV measurement results

4.1 Main jet flow characteristics

Figure 3a, b shows cross-jet profiles of the dimensionless time-averaged velocity magnitude (|V|/V 0) and of the turbulence intensity \(({{I}_{\text{uv}}}=|{{v}_{\text{RMS}}}|/{{V}_{0}}=\sqrt{u_{\text{RMS}}^{2}+v_{\text{RMS}}^{2}}/{{V}_{0}})\) obtained from the PIV measurements in ROI2. The values are obtained in the vertical centreplane for Re = 7200 to 13,500 at two different downstream locations: y = 4w jet for w jet = 8 mm and y = 2w jet for w jet = 16 mm. These locations are chosen to provide information on flow conditions as close as possible to the inlet while avoiding erroneous data caused by reflections and visual obstruction by the top front beam of the water channel.

a Dimensionless mean velocity magnitude (|V|/V 0) and b turbulence intensity I uv near jet inlet (at y = 2w jet for w jet = 16 mm, at y = 4w jet for w jet = 8 mm). c Dimensionless mean velocity magnitude (|V|/V 0) and d streamwise turbulence intensity I v near jet inlet (at y = 2w jet for Re = 13,000, at y = 4w jet for Re = 13,500) compared to other studies. e Dimensionless mean velocity magnitude (|V|/V 0) and f turbulence intensity near jet inlet at yʹ = 2.8w jet

Figure 3a shows that the time-averaged profiles for the velocity magnitude clearly resemble a top-hat distribution. The velocity profiles for different Re values for w jet = 16 mm show good agreement among each other, which is also the case for the profiles of w jet = 8 mm. However, the velocity profiles for different jet widths do show some differences near the edges of the jet (|x|/w jet = 0.5), with larger gradients \(\partial (\left| V \right|/{{V}_{0}})/\partial (x/{{w}_{\text{jet}}})\) for w jet = 16 mm, while the actual gradients \(\partial ~\left( |V| \right)/\partial x\) are larger for w jet = 8 mm. Figure 3b shows that the turbulence intensity is highest in the shear layer due to the high velocity gradients (high turbulence production) in this area. The maximum values are equal to I uv ≈ 0.4 for w jet = 16 mm and I uv ≈ 0.44 for w jet = 8 mm. The turbulence intensities in the core of the jet reach I uv ≈ 0.05 for w jet = 16 mm and I uv ≈ 0.06 for w jet = 8 mm. There is no clear tendency visible in terms of different Re; however, the turbulence intensities in the central and shear layer regions are slightly higher for w jet = 8 mm (AR = 37.50) than for w jet = 16 mm (AR = 18.75), which is partly attributed to the higher actual gradients for w jet = 8 mm.

To indicate whether the flow has laminar, turbulent or transitional conditions near the jet inlet at the beginning of the potential core, the boundary layer displacement thickness δ * and momentum thickness θ are calculated as follows (Deo et al. 2007a):

The displacement thickness δ * for w jet = 16 mm is about 0.05w jet to 0.06w jet, while the momentum thickness θ ≈ 0.03w jet. This results in a shape factor H = δ */θ ≈ 1.6–2, indicative of turbulent flow. Note that the characteristic values of the shape factor for laminar and turbulent boundary layers are H = 2.3–3.5 and H = 1.3–2.2, respectively (Schlichting 1979). For w jet = 8 mm, the displacement and momentum thicknesses are δ * ≈ 0.06w jet to 0.07w jet and θ ≈ 0.03w jet to 0.04w jet, respectively, yielding a shape factor of around H ≈ 1.7–1.8. That means that the measured flow conditions near the inlet are turbulent.

Figure 3c, d compares the measured profiles of mean velocity and turbulence intensity (w jet = 16 mm: AR = 18.75, Re = 13,000; w jet = 8 mm: AR = 37.50, Re = 13,500) with those by Deo et al. (2007a) (A R = 20 and 30; Re = 18,000), Maurel and Solliec (2001) (AR = 18; Re = 27,000) and Koched et al. (2011) (AR = 20; Re = 11,000). Note that Deo et al. (2007a) provided the inlet distributions of the mean velocity and the turbulence intensity at a distance y = 0.2w jet from the jet inlet; Maurel and Solliec (2001) and Koched et al. (2011) measured the profiles at the jet inlet (y = 0). Figure 3c shows that the mean velocity profiles of Deo et al. (2007a) and Maurel and Solliec (2001) have a more pronounced top-hat distribution than our experimental data. This can be explained by the fact that our profiles were taken at a certain distance downstream of the nozzle, where the jet shear layer has already grown to some extent and consumed part of the jet potential core. In addition, the geometrical configurations of the contractions in the aforementioned studies differ from each other. Deo et al. (2007a) used a radially-shaped contraction, Maurel and Solliec (2001) used a bell-shaped contraction with a long converging section, and Koched et al. (2011) used a long sharp-edged nozzle. This results in variations of the boundary layer development upstream of the inlet, causing dissimilarity of the inlet conditions, which can explain the differences found here. Figure 3d shows a comparison of the profiles of the streamwise turbulence intensity (I v) with those from literature. Maurel and Solliec (2001) did not provide turbulence intensity profiles near the inlet, but only its range from 1.6 to 2.8% for different Re, assuming a uniform distribution. Note that in the remainder of the paper I uv is used, based on the turbulent fluctuations in both the streamwise and lateral directions. The values reported in the mentioned studies lie below I v = 0.2 and are lower than the values measured in our experiments. This is again attributed to differences in nozzle geometries, Re at the jet inlet and different downstream sampling positions.

The centreline velocity of plane jets varies as a function of \(\text{1}/\sqrt{y}\), where y is the downstream distance from the jet inlet (e.g., Scorer 1987; Pope 2000). Based on these centreline velocity distributions in the vertical centreplane, the vertical distances y 0 between jet inlet (y = 0) and the kinematic virtual jet origins (yʹ = 0) are defined. The virtual origin lies at y 0 ≈ 2.3w jet for w jet = 8 mm, and y 0 ≈ −0.8w jet for w jet = 16 mm. That means that the values for the profiles presented in Fig. 3a–d are taken at yʹ ≈ 1.7w jet for w jet = 8 mm, and yʹ ≈ 2.8w jet for w jet = 16 mm, where yʹ is the downstream distance from the kinematic virtual jet origin. To provide a clear comparison of the flow development at the beginning of the potential core between two different ARs, Fig. 3e, f compares cross-jet profiles of the mean velocity and the turbulence intensity near the jet inlet taken at the same distance from the virtual jet origin, i.e., yʹ ≈ 2.8w jet. The mean velocity profiles for w jet = 8 mm resemble rather parabolic than top-hat profiles, meaning that the jet spreads faster laterally and that ambient fluid has entrained the jet to a larger extent resulting in more developed shear layers than for w jet = 16 mm.

Figure 4a shows the dimensionless mean streamwise velocity along the jet centreline. From the mean velocity decay, the length of the potential core (h p) is defined as the distance from the jet nozzle where the local centreline mean velocity remains more than or equal to 98% of the inlet mean jet velocity, i.e., V 0,y /V 0 ≥ 0.98 (Deo et al. 2007a). The length of the potential core measured starting from the jet inlet is h p ≈ 4.8w jet for w jet = 16 mm, whereas it is h p ≈ (6.1–7.0)w jet for w jet = 8 mm. This is caused by differences in the jet inlet conditions, i.e., nozzle AR and velocity at the jet inlet. Note that these distances do not take into account the positions of the virtual jet origins. Deo et al. (2007a) showed that the ratio h p /w jet for jets with equal Re increases with A R of the nozzle, which is in line with the present results. The centreline velocity decreases to the half of its inlet value V 0 at y ≈ 0.85h jet (= 19w jet) for w jet = 16 mm and at y ≈ 0.55h jet (= 25w jet) for w jet = 8 mm.

a Dimensionless mean streamwise velocity along jet centreline (V 0,y /V 0). Orange dashed lines indicate impingement region. b Ratio (V 0/V 0,y )2 along jet centreline. Orange dashed lines indicate regions with close-to-linear distribution to define the jet decay rate. Note the double scale for y/w jet on the right of Fig. 4a, b: in black for w jet = 8 mm and in cyan for w jet = 16 mm

Figure 4b shows the decay of the inverse of the dimensionless mean centreline velocity squared as a function of y. The jet decay rate K u is defined as K u = (V 0/V 0,y )2/((y−y 0)/w jet), with y 0 the vertical distance between jet inlet and the kinematic virtual jet origin. It can be quantified as the slope of the velocity distribution in Fig. 4b where near-linear behaviour is observed. The jet with w jet = 8 mm (AR = 37.50) has a higher decay rate than the jet with w jet = 16 mm (AR = 18.75), which is also in line with the findings of Deo et al. (2007a) regarding the influence of nozzle AR. The values for w jet = 16 mm are about K u ≈ 0.14–0.15, and for w jet = 8 mm K u ≈ 0.17–0.18 meaning that entrainment rate of the ambient fluid within this region is higher for w jet = 8 mm (i.e. for higher AR). In previous experimental studies of free plane turbulent jets with sidewalls in the range of Re = 6000–16,000, e.g., Jenkins and Goldschmidt (1973), Browne et al. (1983), Thomas and Chu (1989), Sakai et al. (2006), Deo et al. (2007a), Suresh et al. (2008) and Alnahhal and Panidis (2009), a range of values of K u from 0.11 to 0.22 was reported, which encompasses the values found in the present study.

The impingement region can be identified as the region in the vicinity of the impingement plane with a linear decrease of the centreline velocity (see Fig. 4a), the height of which can be denoted with h i . Figure 4a shows that h i ≈ 0.12h jet for w jet = 16 mm and h i ≈ 0.13h jet for w jet = 8 mm. These heights correspond well with the values by Maurel and Solliec (2001) and Koched et al. (2011), who report impingement region heights of h i = (0.12–0.13)h jet and h i = (0.10–0.13)h jet, respectively. For a better estimation of the impingement height, additional flow quantities, such as centreline distribution of turbulence intensity and Reynolds shear stress in the vertical centreplane, will be analysed and described later.

The linear distribution in Fig. 4b indicates the self-similarity of normalised mean velocity in the region 0.35 ≤ y/h jet ≤ 0.75 for w jet = 16 mm and 0.20 ≤ y/h jet ≤ 0.75 for w jet = 8 mm. When converted to w jet, these values result in 7.5 ≤ y/w jet ≤ 17 for w jet = 16 mm and 9 ≤ y/w jet ≤ 33 for w jet = 8 mm. Beyond y/h jet > 0.75, the jet is influenced by strong three-dimensional effects which occur due to the presence of the impingement wall and sidewalls that prevent the jet to spread in the spanwise direction. To further investigate the existence of self-similarity in the flow, the cross-jet profiles along the jet height are examined and compared with a Gaussian distribution: V y /V 0,y = exp(a(x/δ 0.5)2), where a = −0.693 (Rajaratnam 1976). This equation was used by, among others, Namer and Otugen (1988), Deo et al. (2007a) and Suresh et al. (2008). As jets with the same w jet result in identical distributions for the investigated range of Reynolds numbers, only results for cases I and II, the parameters of which are specified in Table 1, are reported in Fig. 5. Note that the profiles are provided at distances yʹ from the virtual jet origins. From Fig. 5, it can be concluded that the velocity profiles resemble a Gaussian distribution for 5.9 ≤ yʹ/w jet ≤ 20.1 for w jet = 16 mm and 4.8 ≤ yʹ/w jet ≤ 35.1 for w jet = 8 mm.

Figure 6 presents the turbulence intensity along the jet centreline for the two jet widths and for different Re values. The data from measurement sets at ROI2 and ROI3 are combined. A slight mismatch is observed around y/h jet ≈ 0.5–0.65 for w jet = 16 mm and y/h jet ≈ 0.5–0.6 for w jet = 8 mm. This relatively small mismatch (6%) is likely to be caused by differences in interrogation area size between ROI2 and ROI3 due to different velocity magnitudes in these regions. Interrogation area size acts as a different spatial filter on the PIV data possibly leading to different turbulence statistics (e.g., Keane and Adrian 1990; Forliti et al. 2000). The shapes of the turbulence intensity profiles for the two jet widths are different due to different nozzle ARs and velocities at the jet inlet. The maximum turbulence intensity at the centreline reaches I uv ≈ 0.21 at y/h jet ≈ 0.55 (equivalent to y/w jet ≈ 12.4) and I uv ≈ 0.19 at y/h jet ≈ 0.25 (equivalent to y/w jet ≈ 11.3) for w jet = 16 and 8 mm, respectively. This gradual increase of the turbulence intensity downstream of the jet inlet can be attributed to the growth of vorticity in the shear layer, which consumes the potential core and causes higher velocity fluctuations along the centreline of the jet. At the same time, the local jet velocity downstream of the jet inlet is decreasing, resulting in higher turbulence intensities. The same behaviour of centreline turbulence intensity was observed by e.g. Browne et al. (1983) and Deo et al. (2007a). Slightly higher values of turbulence intensity for w jet = 16 mm can be explained by smaller AR compared to w jet = 8 mm that causes stronger influence of sidewalls and enhances velocity fluctuations (Deo et al. 2007a). Downstream of the locations of maximum turbulence intensities a linear decrease is present until I uv ≈ 0.16 and I uv ≈ 0.13 for w jet = 16 and 8 mm, respectively. This linear decrease is present until the jet impingement region. In the impingement region, the shape of the turbulence intensity profiles for the two different jet widths is similar, and the turbulence intensities show an increase to I uv ≈ 0.21 and I uv ≈ 0.16 for w jet = 16 and 8 mm, respectively. Maximum values are reached at y/h jet ≈ 0.99 for w jet = 16 mm and y/h jet ≈ 0.97 for w jet = 8 mm. This increase is caused by the compression of the vortices in the streamwise direction due to the presence of the impingement plane causing stretching of the vortices in the lateral direction. The jet flow near the impingement plane diverges to two opposite lateral directions and forms so-called stretching wall vortices (e.g., Sakakibara et al. 2001) enhanced by vorticity from upstream of the impinging jet and by the high pressure at the stagnation zone (e.g., Tsubokura et al. 2003).

Figure 7 shows the cross-jet profiles of turbulence intensity for case I (Fig. 7a) and case II (Fig. 7b). The distribution of I uv near the jet centreline downstream of yʹ/w jet = 5.9 smoothens out to about 0.2 for case I and to about 0.15 for case II due to entrainment of the ambient fluid and shear layer growth, which also results in a decrease of bulk jet velocity. Within 2.8 ≤ yʹ/w jet ≤ 7.9, the turbulence intensities at the jet centreline and shear layer for case II are slightly higher than for case I at the same relative downstream distances. The opposite is valid when the flow approaches the impingement plane (yʹ/w jet ≥ 12.1), where turbulence intensities for case I are slightly higher. To determine at which regions of the jet the turbulence intensity achieves self-similarity, the cross-jet profiles of turbulence intensity along the jet have been analysed at more lines than depicted in Fig. 7 (not all profiles are included in Fig. 7 for clarity). It appears that the profiles of the turbulence intensity tend to exhibit self-similar behaviour within regions of 12.1 ≤ yʹ/w jet ≤ 18.4 for case I and 12.1 ≤ yʹ/w jet ≤ 20.1 for case II, which partially comprise the regions of self-similar behaviour found for cross-jet velocity profiles.

4.2 Velocity contours and velocity vectors

Figure 8 shows contours of the dimensionless mean streamwise velocity and the mean velocity vectors in the vertical centreplane for case I (Fig. 8a, c) and case II (Fig. 8b, d). The white areas at the top and bottom parts of the figure indicate zones where erroneous measurement data due to obstructions by the structural beam of the water channel and reflections from the surfaces of the water channel are excluded.

The jet half-width δ 0.5 and the nominal jet boundaries 2δ 0.5 (e.g. Fan 1967; Jirka 2004; Socolofsky et al. 2013) are indicated by the dashed and dotted white lines, respectively. The near-linear variation of the jet half-width δ 0.5 along jet centreline within the intermediate jet region characterises the spreading rate of the jet K y = dδ 0.5/dy (Pope 2000), which is equal to K y = 0.10 for case I and K y = 0.12 for case II. Experimental studies for free plane turbulent jets with sidewalls in the range of Re = 6000–16,000, e.g., Jenkins and Goldschmidt (1973), Browne et al. (1983), Thomas and Chu (1989), Sakai et al. (2006), Deo et al. (2007a,b) and Suresh et al. (2008), reported values of K y in the range from 0.05 to 0.11. The jet spreading rate for case I lies within the range from literature, while the spreading rate for case II falls just outside this range. A possible explanation could be that although the jets considered in the aforementioned studies have an Re range (6000–16,000) and an AR range (20–35) similar to the values in our experiments, there are some differences in the contractions used in various studies. Jenkins and Goldschmidt (1973), Browne et al. (1983), Thomas and Chu (1989) and Suresh et al. (2008) conducted experiments with a gradually converging contraction; Sakai et al. (2006) applied a gradually converging contraction but without a rectangular section upstream of the jet inlet; and Deo et al. (2007a, b) used a contraction with radially-shaped edges but without a conditioning section.

The nominal jet boundaries are determined based on the distance of two jet half-widths δ 0.5 from the jet centreline (2δ 0.5) along the jet height. The angles between the jet boundaries and jet axis in the intermediate jet region are about 11°–12° for case I and about 12°–12.5° for case II. The slope of the jet boundaries indicates the jet entrainment rate. Thus, entrainment of ambient fluid is slightly more intensive for case II than for case I. The larger opening angle, and thus the more intensive entrainment and jet spreading can be caused by the higher turbulence intensities in the shear layer close to the jet inlet for w jet = 8 mm (case II) compared to w jet = 16 mm (case I) (as shown in Fig. 3b). Note that the development of the jet half-width δ 0.5 and the nominal jet boundaries 2δ 0.5 is identical for jets with the same w jet but different Reynolds numbers.

Figure 9 provides contours of the dimensionless absolute mean lateral velocity (abs(U)/V 0) in the vertical centreplane and indicates the lines where the lateral velocity component U = 0 and changes its direction. The plots indicate the growth of the lateral component of velocity near the jet centreline at the height y/h jet ≈ 0.7–0.75 due to the influence of the impingement plane. Recirculation occurs at the top part of the water channel, where the lateral velocity component reaches abs(U) = 0.08V 0.

4.3 Instantaneous velocity, vorticity ω Z , and Okubo-Weiss function Q

Contours of the dimensionless instantaneous velocity magnitude (|v|/V 0) from the measurements in ROI2 for cases I and II are depicted in Fig. 10 and indicate widening of the jet and growing of its shear layer due to entrainment of ambient fluid on either side of the jet. This entrainment is caused by vorticity induced in the jet shear layer due to high velocity gradients. At this Re value the flow is highly turbulent and it is difficult to clearly distinguish individual vortices in the jet with the present measurement resolution of 16 × 12 pixels per interrogation area of 1.8 × 1.4 mm2.

Contours of dimensionless instantaneous velocity magnitude and instantaneous velocity vectors in the vertical centreplane for a case I; b case II. Note that the Fig. 10b provides only part of the data for the measurement region ROI2

The distributions of the instantaneous vorticity for cases I and II (Fig. 11a, c) indicate that the highest levels of vorticity occur close to the inlet induced by the shear layer. The absolute maximum values of vorticity reach Ω z ≈ 160 μs− 1 for case I and Ω z ≈ 400 μs− 1 for case II. Although not presented here, it is worth mentioning that for the nozzle with w jet = 16 mm and Re = 13,000, the vorticity reaches Ω z ≈ 250 μs− 1, while for the nozzle with w jet = 8 mm and Re = 13,500 the value reaches Ω z ≈ 650 μs− 1. So, for a similar range of Reynolds numbers the vorticity for the jet width w jet = 8 mm is at least two times higher than for the jet width w jet = 16 mm, which can be attributed to the higher velocities (same Re and smaller width) and higher mean velocity gradients at the jet inlet for w jet = 8 mm. Note that the gradients \({\partial (\left| V \right|/{{V}_{0}})}/{\partial (x/{{w}_{\text{jet}}})}\) at the jet inlet are larger for w jet = 16 mm, while the actual gradients \(\partial (|V|)/\partial x\) are larger for w jet = 8 mm.

To analyse the presence of vortical structures in the flow domain the Okubo–Weiss function is used. The Okubo-Weiss function was independently defined by Okubo (1970) and Weiss (1991). Based on the Okubo–Weiss function, the Q criterion for the vertical centreplane (z = 0) can be defined as follows:

In this equation, the first two terms denote the normal and shear strain component, respectively, and the last term represents the vorticity ω z . The strain-dominated regions can be identified by Q > 0, while rotation-dominated regions can be identified by Q < 0. The Okubo–Weiss function is valid for two-dimensional flow and has been successfully used by, among others, Vosbeek et al. (1997), Isern-Fontanet et al. (2004), Molenaar et al. (2004), Cieślik et al. (2010) and van Hooff et al. (2012). Figure 11b, d shows distributions of Q for cases I and II, respectively, which reveal that along the jet centreline within the potential core region, the Q values lie around 0, which is also the case in the background flow on both sides of the jet. The values Q < 0 indicate turbulent eddy cores surrounded by circulation areas, while the regions with Q > 0 indicate the strain dominated regions.

4.4 Reynolds shear stress

Figure 12 shows the distribution of the dimensionless Reynolds shear stress (uʹvʹ/V 20 ) in the vertical centreplane for cases I and II. These data are analysed for each measurement set and are used to define the impingement region height. The Reynolds shear stress reaches its maximum value in the shear layer where velocity gradients and turbulence intensity are high. The change in sign of the Reynolds stresses occurs at the centreline of the jet due to symmetry of the time-averaged flow, and at the transition region from the jet to a wall jet, which defines the impingement region. For both jet widths, the impingement height is defined based on the Reynolds shear stress and is about 0.1h jet. This value corresponds with the impingement region height based on the dimensionless centreline velocity magnitudes in Fig. 4 of this paper, and also with the values reported in other studies (Maurel and Solliec 2001; Koched et al. 2011).

5 Discussion

In this study, 2D particle image velocimetry (PIV) measurements are performed for the analysis of plane turbulent impinging jets (PTIJs) at moderate Reynolds numbers (Re = 7200–13,500). Two jet configurations are considered: (1) w jet = 8 mm (AR = 37.50) and jet height h jet = 45w jet, (2) w jet = 16 mm (AR = 18.75) and jet height h jet = 22.5w jet. Note that the absolute jet height for both configurations is h jet = 360 mm. In addition, flow visualisations are performed to analyse the flow pattern, which shows cyclic jet flapping.

Based on the centreline and cross-jet velocity and the turbulence intensity profiles, the present study shows that PTIJs behave as a free plane turbulent jet up to at least y/h jet ≈ 0.75 for the two jet widths, which is in line with the study of Gutmark et al. (1978).

The jet decay rate K u was quantified by analysing the centreline velocity distribution and the following values were obtained: K u ≈ 0.14–0.15 for w jet = 16 mm and K u ≈ 0.17–0.18 for w jet = 8 mm. These values from the current experimental study of PTIJs are within the range of jet decay rates for free jets as reported in the literature. In addition, the spreading rate of the jet K y was defined by examining the development of the jet half-width δ 0.5 along the jet height: K y ≈ 0.10 for w jet = 16 mm and K y ≈ 0.12 for w jet = 8 mm. These comparisons indicate that for jet flows with the same Reynolds number decay of the centreline velocities and entrainment of ambient fluid by the jet is more intensive for w jet = 8 mm (AR = 37.50) than for w jet = 16 mm (AR = 18.75). A comparison with values from previous experimental studies shows that the jet spreading rate for w jet = 16 mm lies within the range reported in the literature, whereas the spreading rate for w jet = 8 mm falls just outside this range. This difference can be explained by the variation of the jet inlet conditions between these experiments, namely the configurations of the contractions used.

Future research of the authors will include experiments for an extended Reynolds number range, i.e. higher Re values (higher velocities). Moreover, 3D PIV measurements will be performed to address the influence of sidewalls on the flow development within the potential, intermediate and impingement regions of the current jet configuration, as was done in studies of Alnahhal and Panidis (2009) and Deo et al. (2007b). Finally, the experimental results will be applied for turbulence model validation in CFD simulations of PTIJs, including Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes and large eddy simulations.

6 Conclusions

This paper provides a detailed experimental analysis of plane turbulent impinging jets (PTIJs) with two jet widths (8 and 16 mm) at moderate Reynolds numbers (7200–13,500) issued on a horizontal plane at a fixed relative distance of 22.5 and 45 jet widths. There is a clear scarcity on similar experimental studies that aim at understanding the flow and to provide a database for comparison with numerical models. Prior to the PIV measurements, flow visualisations are performed to analyse the flow pattern.

For each jet width and for a range of Reynolds numbers, three sets of measurement data are obtained and examined: (1) the entire measurement region (ROI1); (2) the region close to the inlet (ROI2); and (3) the region close to the impingement plane (ROI3) to increase the measurement resolution in this area. The measurement data include time-averaged quantities of velocity, turbulence intensity and Reynolds shear stress measured in the vertical centreplane. In addition, instantaneous fields of velocity and vorticity have been analysed.

From the obtained results the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

The flow visualisations show the presence of cyclic flapping of the impinging jet.

-

The following regions of the jet are distinguished: (1) the potential core region with the centreline velocity more than or equal to 98% of the inlet jet velocity (h p = 4.8w jet for w jet = 16 mm, h p = (6.1–7.0)w jet for w jet = 8 mm); (2) the intermediate region with decaying centreline velocity comprising the transition region from the potential core to the developed region with largely self-similar profiles for mean velocity and turbulence intensity; and (3) the impingement region, where the flow is influenced by the pressure created by the opposing impingement plane (h i ≈ (0.10 − 0.13)h jet).

-

Calculation of the shape factor (H = δ */θ) near the inlet indicated that the flow near the jet inlet was turbulent.

-

The profiles of centreline mean velocity, cross-jet mean velocity and turbulence intensity show that the PTIJs considered in the present study behave as a free plane turbulent jet until y/h jet ≈ 0.7–0.75.

-

The self-similarity and self-preservation of the jet is shown by fitting the actual velocity profiles with theoretical profiles of a Gaussian distribution and analysing the cross-jet profiles of the turbulence intensity depending on the jet half-width. The investigated jet configurations exhibit self-similar behaviour of cross-jet velocity profiles between 5.9 ≤ y′/w jet ≤ 20.1 for w jet = 16 mm, and between 4.8 ≤ yʹ/w jet ≤ 35.1 for w jet = 8 mm. The profiles of turbulence intensity tend to achieve self-similarity between 12.1 ≤ yʹ/w jet ≤ 18.4 for w jet = 16 mm, and between 12.1 ≤ yʹ/w jet ≤ 20.1 for w jet = 8 mm.

-

The jet decay rate K u is quantified by analysing the centreline velocity distribution and the following values are obtained: K u ≈ 0.14–0.15 for w jet = 16 mm and K u ≈ 0.17–0.18 for w jet = 8 mm.

-

The spreading rate K y of the jet is defined by examining the development of the jet half-width δ 0.5 along the jet height: K y ≈ 0.10 for w jet = 16 mm and K y ≈ 0.12 for w jet = 8 mm.

-

A distinct influence of the nozzle aspect ratio on the development of the profiles of the centreline mean velocity and the turbulence intensity in the streamwise direction was found. Jet nozzles with a higher aspect ratio showed more intensive entrainment and a faster decay of the centreline velocity for the same value of the jet Reynolds number. This is caused by the higher inlet jet velocity, resulting in higher mean velocity gradients, higher turbulence intensity and higher vorticity in the shear layer.

References

Alnahhal M, Panidis T (2009) The effect of sidewalls on rectangular jets. Exp Therm Fluid Sci 33(5):838–851

Antonia RA, Browne LWB, Chambers AJ, Rajagopalan S (1983) Budget of the temperature variance in a turbulent plane jet. Int J Heat Mass T 26(1):41–48

Ashforth-Frost S, Jambunathan K, Whitney CF (1997) Velocity and turbulence characteristics of a semiconfined orthogonally impinging slot jet. Exp Therm Fluid Sci 14(96):60–67

Beitelmal AH, Saad M, Patel CD (2000) The effect of inclination on the heat transfer between a flat surface and an impinging two-dimensional air jet. Int J Heat Fluid Flow 21:156–163

Beitelmal AH, Shah AJ, Saad MA (2006) Analysis of an impinging two-dimensional jet. J Heat Transf 128(3):307

Browne LWB, Antonia RA, Rajagopalan S, Chambers AJ (1983) Interaction region of a two-dimensional turbulent plane jet in still air. In: Dumas R, Fulachier L (eds), Structure of Complex Turbulent Shear Flow, vol 1, pp 411–419

Camci C, Herr F (2002) Forced convection heat transfer enhancement using a self-oscillating impinging planar jet. J Heat Transf 124:770

Cartwright WG, Russell PJ (1967) Characteristics of a turbulent slot jet impinging on a plane surface. Proc Inst Mech Eng 182:309–319

Chiriac V, Ortega A (2002) A numerical study of the unsteady flow and heat transfer in a transitional confined slot jet impinging on an isothermal surface. Int J Heat Mass Transf 45(6):1237–1248

Cieślik AR, Kamp LPJ, Clercx HJH, van Heijst GJF (2010) Three-dimensional structures in a shallow flow. J Hydro Environ Res 4:89–101

Deo RC, Mi J, Nathan GJ (2007a) The influence of nozzle aspect ratio on plane jets. Exp Therm Fluid Sci 31(8):825–838

Deo RC, Nathan GJ, Mi J (2007b) Comparison of turbulent jets issuing from rectangular nozzles with and without sidewalls. Exp Therm Fluid Sci 32(2):596–606

Fan L-N (1967) Turbulent buoyant jets into stratified or flowing ambient fluids. W. M. Keck Laboratory of Hydraulics and Water Resources Report, 15. California Institute of Technology, Pasadena

Forliti DJ, Strykowski PJ, Debatin K (2000) Bias and precision errors of digital particle image velocimetry. Exp Fluids 28(5):436–447

Gardon R, Akfirat JC (1965) The role of turbulence in determining the heat-transfer characteristics of impinging jets. Int J Heat Mass T 8:1261–1272

Goldschmidt VW, Bradshaw P (1973) Flapping of a plane jet. Phys Fluids 16(3):354–355

Gutmark E, Wolfshtein M, Wygnanski I (1978) The plane turbulent impinging jet. J Fluid Mech 88:737

Guyonnaud L, Solliec C, Dufresne de Virel M, Rey C (2000) Design of air curtains used for area confinement in tunnels. Exp Fluids 28(4):377–384

Isern-Fontanet J, Font J, Garcı´a-Ladona E, Emelianov M, Millot C, Taupier-Letage I (2004) Spatial structures of anticyclonic eddies in the Algerian basin (Mediterranean Sea) analyzed using the Okubo-Weiss parameter. Deep-Sea Res II(51):3009–3028

Jenkins PE, Goldschmidt VW (1973) Mean temperature and velocity measurements in a plane turbulent jet. J Fluid Eng 95:81–584

Jirka GH (2004) Integral model for turbulent buoyant jets in unbounded stratified flows. Part I: single round jet. Environ Fluid Mech 4(1):1–56

Keane RD, Adrian RJ (1990) Optimization of particle image velocimeters. Part I. Double pulsed systems. Meas Sci Technol 1(11):1202–1215

Koched A, Pavageau M, Aloui F (2011) Experimental investigations of transfer phenomena in a confined plane turbulent impinging water jet. J Fluid Eng 133(6):061204 (1–13)

Korger M, Krizek F (1966) Mass-transfer coefficient in impingement flow from slotted nozzles. Int J Heat Mass Transfer 9:337–344

Loubière K, Pavageau M (2008) Educing coherent eddy structures in air curtain systems. Chem Eng Process 47(3):435–448

Maurel S, Solliec C (2001) A turbulent plane jet impinging nearby and far from a flat plate. Exp Fluids 31:687–696

Molenaar D, Clercx HJH, van Heijst GJF (2004) Angular momentum of forced 2D turbulence in a square no-slip domain. Phys D 196:329–340

Namer I, Ötügen MV (1988) Velocity measurements in a plane turbulent air jet at moderate Reynolds numbers. Exp Fluids 6(6):387–399

Okubo A (1970) Horizontal dispersion of floatable trajectories in the vicinity of velocity singularities such as convergencies. Deep Sea Res 17:445–454

Pope SB (2000) Turbulent flows. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Prasad AK (2000) Particle image velocimetry. Curr Sci India 79(1):51–60

Rajaratnam N (1976) Turbulent jets. Elsevier Scientific, New York

Sakai Y, Tanaka N, Kushida T (2006) On the development of coherent structures in a plane jet. JSME Int J B Fluid Therm Eng 49(1):115–124

Sakakibara J, Hishida K, Phillips WRC (2001) On the vortical structure in a plane impinging jet. J Fluid Mech 434:273–300

Schlichting H (1979) Boundary-layer theory, 7th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Scorer RS (1978) Environmental aerodynamics. Ellis Horwood, Chichester

Suresh PR, Sundararajan T, Das SK (2008) Experimental investigation of the influence of momentum thickness on the development of a slightly heated plane jet. Int Commun Heat Mass 35(3):282–288

Thomas FO, Chu HC (1989) An experimental investigation of the transition of a planar jet: subharmonic suppression and upstream feedback. Phys Fluids A Fluid 1(9):1566–1587

Tsubokura M, Kobayashi T, Taniguchi N, Jones WP (2003) A numerical study on the eddy structures of impinging jets excited at the inlet. Int J Heat Fluid Flow 24(4):500–511

van Hooff T, Blocken B, Defraeye T, Carmeliet J, van Heijst GJF (2012) PIV measurements of a plane wall jet in a confined space at transitional slot Reynolds numbers. Exp Fluids 53(2):499–517

Varieras D, Brancher P, Giovannini A (2006) Self-sustained oscillations of a confined impinging jet. Flow Turbul Combust 78(1):1–15

Vosbeek PWC, van Geffen JHGM, Meleshko VV, van Heijst GJF (1997) Collapse interactions of finite-sized two-dimensional vortices. Phys Fluids 9:3315

Weiss J (1991) The dynamics of enstrophy transfer in twodimensional hydrodynamics. Phys D 48:273–294

Yoshida H, Suenaga K, Echigo R (1990) Turbulence structure and heat transfer of a two-dimensional impinging jet with gas-solid suspensions. Int J Heat Mass T 33(5):859–867

Zhou DW, Lee SJ (2007) Forced convective heat transfer with impinging rectangular jets. Int J Heat Mass T 50(9–10):1916–1926

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Geert-Jan Maas and Stan van Asten (Laboratory of the unit Building Physics and Services) and Ad Holten (Fluid Dynamics Laboratory) at Eindhoven University of Technology for their assistance in the development and construction of the experimental set-up and their support during the measurements. Twan van Hooff is currently a postdoctoral fellow of the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO) and acknowledges its financial support (Project FWO 12R9715N).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Khayrullina, A., van Hooff, T., Blocken, B. et al. PIV measurements of isothermal plane turbulent impinging jets at moderate Reynolds numbers. Exp Fluids 58, 31 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-017-2315-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-017-2315-0