Abstract

The objective of this work is to investigate the feasibility of intense laser-beam propagation through optical fibers for temperature and species concentration measurements in gas-phase reacting flows using coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) spectroscopy. In particular, damage thresholds of fibers, nonlinear effects during beam propagation, and beam quality at the output of the fibers are studied for the propagation of nanosecond (ns) and picosecond (ps) laser beams. It is observed that ps pulses are better suited for fiber-based nonlinear optical spectroscopic techniques, which generally depend on laser irradiance rather than fluence. A ps fiber-coupled CARS system using multimode step-index fibers is developed. Temperature measurements using this system are demonstrated in an atmospheric pressure, near-adiabatic laboratory flame. Proof-of-concept measurements show significant promise for fiber-based CARS spectroscopy in harsh combustion environments. Furthermore, since ps-CARS spectroscopy allows the suppression of non-resonant background, this technique could be utilized for improving the sensitivity and accuracy of CARS thermometry in high-pressure hydrocarbon-fueled combustors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Various nonlinear spectroscopic techniques exist for measuring temperature, velocity, and chemical-species concentrations in gas-phase reacting flows (Eckbreth 1996; Gord et al. 2008). Among those techniques, broadband multiplex coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) has been proved to be the most accurate and promising method for measuring temperature and major-species concentrations under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions (Eckbreth 1996; Roy et al. 2010) because of its ability to acquire single-shot spectra of transient phenomena under unsteady flow conditions (Snelling et al. 1994; Hahn et al. 1997; Kuehner et al. 2003; Roy et al. 2010). One of the major requirements for this nonlinear technique is precise spatial and temporal superposition of three laser beams—pump, Stokes, and probe—at the probe volume to generate the CARS signal. Hence, performing state-of-the-art CARS measurements based on free-standing optics in harsh environments such as combustors and gas-turbine-engine test facilities poses significant challenges due to vibration, thermal transients, and unconditioned humidity associated with these environments. Optical fibers, because of their capability to provide flexibility in transmitting light to a remote location, can provide access to such probe volumes, which will simplify the application of CARS-based spectroscopy in harsh environments. Fiber-based CARS spectroscopy has several advantages in such environments: (1) reduced need of free-standing optics in the test-cell environment, (2) ease of alignment of multiple laser beams with flexibility when needed and ability to access non-windowed test sections, (3) isolation of the high-power laser system from harsh environments, and (4) safe, guided, and confined laser delivery.

Recently, several fiber-based CARS systems have been investigated for microscopy in the condensed phase using single-mode fibers (SMFs) (Légaré et al. 2006) and large-mode-area photonic crystal fibers (LMA-PCFs) (Wang et al. 2006). In addition, continuously wavelength-tunable, fiber-based laser light sources have been used to help avoid coupling losses for the CARS input beams (Andersen et al. 2007; Murugkar et al. 2007; Marangoni et al. 2009). In these studies, it has been shown that the pulse energy required for CARS in the condensed phase is considerably below the damage threshold of the fiber (Légaré et al. 2006). In gas-phase reacting flows, because of the lower molecular densities, the effective optical depth is reduced by four to five orders of magnitude, and the pulse energy required for CARS signal generation is approximately four orders of magnitude higher than that required for the condensed phase (Légaré et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2006; Meyer et al. 2007). This high energy requirement for CARS in the gas phase imposes significant constraints on fiber-based CARS because of the intrinsic optical damage threshold of the fibers. The enhanced higher-order nonlinear processes during propagation of intense laser beams through the fiber can also cause spectral broadening of the input laser beam and complicate the spectral analysis of CARS signal.

The CARS process is a special type of four-wave mixing where the pump and Stokes beams generate Raman coherence that is scattered off by the probe beam to obtain the CARS signal. Thus, the signal strength is proportional to the product of the intensities I ~ E/τA of each input laser beam, with E being the pulse energy, τ the pulse length, and A the cross-sectional area at the focal point. Therefore, higher pulse energy, shorter pulse duration, and smaller cross-sectional area of the beam are favorable for increasing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The accuracy and sensitivity of the measurements are determined by the spectral resolution of the CARS system (Eckbreth 1996). For a fiber-based CARS system, the spectral resolution depends on the bandwidth of the fiber-delivered beams (Gord et al. 2009; Hsu et al. 2010). Thus, for acquiring a high-quality CARS signal, retention of the bandwidth of the input laser pulse during propagation through the fibers is an important criterion. Furthermore, sufficient spatial resolution is required for the fiber-based CARS system to achieve accurate “point” measurements of temperature. The spatial resolution of fiber-based CARS depends on the spot size of the focused beam in the probe volume, which is dependent on the quality of the input laser beam, and the geometry of the phase-matching condition such as collinear CARS or a BOXCARS configuration (Eckbreth 1996; Roy et al. 2010). To achieve an accurate point measurement of temperature in a reacting flow, a high-quality beam at the target end of the fiber is required.

Hence, the design and performance of a fiber-based CARS system for gas-phase thermometry is dependent on three vital parameters: (1) delivery of high-energy/irradiance CARS beams for reacting flows, (2) retention of the bandwidth of the input pulse during propagation through the fiber, and (3) delivery of high-quality laser beams at the probe volume. The amount of energy/irradiance that can be delivered in such a system is limited by the damage threshold of the fiber for varying pulse duration, the physical structure of the fiber, and the wavelength of the input laser beam (Wood 1986).

The objective of this study was to investigate the feasibility of delivering intense ns and ps laser pulses through various fibers for CARS spectroscopy in reacting flows. In particular, the optical damage threshold, the output beam quality, the nonlinearities inside the fiber, and the temporal distortion of the input laser pulses were studied in detail. Based on the results of the fiber studies, a proof-of-principle, ps laser-based fiber-coupled collinear CARS system employing multimode step-index fibers (MSIFs) was designed and demonstrated for thermometry of nitrogen (N2) in an atmospheric pressure, nearly adiabatic H2-air flame. It is understood that the spatial resolution of the CARS system using collinear geometry will be significantly lower than the BOXCARS geometry, and the temperature accuracy of the collinear CARS will also suffer due to the spatial averaging of cold and hot region of the reacting flows. The collinear phase-matching geometry was chosen just to explore the feasibility of fiber-based gas-phase CARS spectroscopy.

In Sect. 2 of this paper, the experimental methods used for characterizing fibers for CARS operation are described. In Sect. 3, the investigation of suitable pulse duration for delivering the energy/irradiance required for nonlinear CARS spectroscopy in reacting flows is described. In Sect. 4, the damage threshold and transmission characteristics of various fibers are addressed. In Sect. 5, demonstration and application of fiber-based ps-CARS for temperature measurements in laboratory flames are discussed, followed by a summary in Sect. 6.

2 Experimental methods for testing fiber transmission

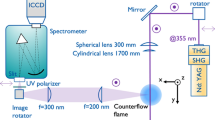

A schematic diagram of the optical system for the investigation of transmission characteristics of 8-ns and 150-ps pulses through various optical fibers is shown in Fig. 1. The 8-ns, 10-Hz laser is an injection seeded, Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (Spectra-Physics, Model Quanta-Ray Pro 350) having pulse energy of ~1.4 J at 532 nm. This laser produces nearly transform-limited pulses with an M 2 ~ 2. The ps laser is a 10-Hz Nd:YAG (EKSPLA, Model SL300) with pulse energy ~200 mJ at 532 nm. The ps laser output is also nearly transform-limited (single-longitudinal-mode oscillator) with an M 2 ~ 2. The pulse length of the ps laser can be varied from 150–600 ps. The beam is down collimated using a 4× telescope system, and the resulting beam diameter is ~2 mm. The collimated beam was passed through a coupling lens into the fiber. The fibers were placed in a six-axis kinematic mount, which was attached to a 1D translational stage that moved along the laser-beam propagation direction. To align the incoming laser beam with the fiber axis, the fiber position was adjusted such that the back-reflected laser light from the front surface of fiber returned along the incoming beam path. The fiber input facet was observed with a camera microscope to optimize the transverse alignment of the laser beam relative to the center of the fiber core. A lens with proper focal length (f = 250 mm) was used to condition the laser beam to form a waist to illuminate ~80% of the fiber core diameter. To prevent fiber damage from the unwanted self-focusing effect and laser-induced air breakdown at high energy, the fiber was installed behind the focal point of a large focal length lens (Allison et al. 1985; Hand et al. 1999). In all fiber damage tests (except fiber bundles and LMA-PCFs, which are limited by the fiber length), the fiber was held with a 90° bend having a radius of ~500 mm. The indicator of fiber damage was a sudden increase in the fiber attenuation. The damage threshold of each fiber was tested three times, and the mean value of the damage threshold is reported. The variation in the data points are within ~±10% from the mean value.

Beam quality for a fiber (straight fiber) is determined by the spatial quality of the beam profile and is quantitatively evaluated using the beam-quality factor M 2 associated with the focusing and collimation capability. Assuming that the divergence of the fiber-delivered beam is the same as that of the diffraction-limited beam, M 2 for the fiber can be estimated as (Sasnett and Johnston 1991)

where W 0 is the diameter of the delivered laser beam at the focal plane and w diff is the diameter of the diffraction-limited beam at the focal point. For the beam-quality measurements, the output beam from the fiber was collimated and then focused onto a CCD camera (Spiricon, Model LW230). After attenuation of the laser beam, the CCD camera was translated along the axis of the beam propagation through the focal plane of lens L5 and the beam diameter W 0, and beam profile was recorded at the focal point. W 0 was determined from 1/e 2 irradiance points of the Gaussian fits to the beam profile using Spiricon’s LBA-PC beam-analysis software. The 1/e 2 method defines the spot diameter as the width at which the beam irradiance becomes 1/e 2 (13.5%) of its peak irradiance (Fischer et al. 2008). The standard ISO second moment method for beam-waist measurement is not used for characterizing the fiber output beam because this method is extremely sensitive to scattered light from fiber cladding and background noise of the CCD, which requires further correction procedures to obtain the more accurate results (Champagne and Bélanger 1995). The w diff can be theoretically estimated as

where D is the beam diameter, f is the focal length of L5, and λ is the laser wavelength. By measuring W 0 and theoretically estimating w diff, the M 2 can be determined using Eq. 1. To verify the accuracy of the M 2 measurement method, the M 2 value of the beam of ps and ns lasers was measured. The factory specifications of M 2 for Nd:YAG ps and ns lasers are in good agreement with our measurements (discrepancy <5%). The Gaussian-fit error associated with the M 2 measurement is given in Table 2.

The nonlinear effect of a fiber is determined by the spectral broadening of the input pulses after propagating through the fiber. Spectral broadening of the fiber-delivered beam was measured using a 0.25-m spectrometer (Acton Research Corporation, Model Spectrapro 275), equipped with a 1,200-grove/mm grating, and the spectrum was recorded using a back-illuminated, unintensified, 2,048 × 512-pixel-array CCD camera (Andor Technologies, Model DU 440BU). The overall dispersion was estimated to be ~1.5 cm−1/pixel. The fine structure of the power spectra is resolved using a high-resolution 1.25-m spectrometer (Jobin Yvon, Model SPEX 1250M) with a resolution of ~0.174 cm−1/pixel (~0.005 nm).

3 Results—suitable pulse regimes for fiber-based CARS: picosecond vs. nanosecond

The main challenge involving fiber-based CARS in gas-phase reacting flows is the transmission of high-irradiance laser beam, required for signal generation, without optically damaging that fiber. Most of the commercially available fibers are made of silica-based materials because of their superior flexibility and higher damage threshold. However, because of the high pulse-energy requirement in realizing fiber-based CARS in gas-phase flows, understanding the damage mechanism of silica fiber is essential for designing the ideal fiber-based CARS system. The temporal duration of the laser pulse is one of the most critical parameters that determines the threshold for laser-induced damage. The threshold irradiance/fluence for bulk silica has been extensively investigated over the pulse duration from tens of ns to a few femtoseconds (fs) (Wood 1986; Stuart et al. 1995; Du et al. 1996; Pronko et al. 1998; Tien et al. 1999). For a pulse duration < 10 ps, the damage mechanism is dominated by an avalanche breakdown process that is determined by the peak irradiance of the laser rather than the fluence (Stuart et al. 1995). The typical characteristic irradiance required for avalanche breakdown of bulk silica is greater than 80 GW/cm2 (Stuart et al. 1996). However, since the typical irradiance required for both ns- and ps-CARS is significantly less than the above-mentioned breakdown irradiance, the effect of the avalanche process on fiber damage is negligible in the design of a fiber-based CARS system. Stuart et al. and Shen et al. reported that for a laser pulse with a duration of 10 ps–10 ns, the fiber damage is dominated primarily by fluence-based lattice heating and thermal processes that involve heating of the conduction-band electrons by incident radiation followed by the transfer of energy to the lattice via electron–phonon interaction (Shen et al. 1989; Stuart et al. 1995, 1996). Since the typical thermal conduction rate (electron–phonon interaction) is ~10 fs (Pronko et al. 1998), Stuart et al. observed that there is sufficient time for the interaction of the energetic electrons with the lattice leading to melting, boiling, or fracturing of the lattice for a laser pulse with τ > 10 ps. The model for lattice heating and thermal processes predicts a τ1/2 dependence of the threshold fluence of bulk silica on pulse duration (Wood 1986), in good agreement with numerous experimental measurements (Wood 1986; Stuart et al. 1995; Du et al. 1996; Tien et al. 1999). A few recent studies based on 8-ns and 14-ps pulses reported by Smith and collaborators showed that the threshold irradiance of bulk silica is higher than the characteristic avalanche irradiance and that the corresponding threshold fluences for ps and ns pulses do not fit a square-root pulse-duration scaling rule (Smith and Do 2008; Smith et al. 2008). They reported that the observed higher damage-threshold fluence and different pulse-duration effect, when compared to those of the previous damage studies (Wood 1986; Stuart et al. 1995; Du et al. 1996; Tien et al. 1999), could result from the use of a small focal spot size and single-longitudinal-mode pulses to suppress the stimulated Brillouin scattering (SBS) and self-focusing effects (Smith and Do 2008; Smith et al. 2008, 2009). Based on an experimental and theoretical investigation, Smith et al. concluded that the bulk damage mechanism for a pulse duration of 14 ps–8 ns pulses in fused silica is dominated by irradiance rather than fluence (Smith and Do 2008; Smith et al. 2008). See Table 4 in the “Appendix” that lists a review of the damage thresholds reported in the literature for fused silica corresponding to mechanisms related to bulk damage, surface damage, and core–clad interface damage in the fibers in ns and ps regime.

The energy and corresponding power for damage of a 1-m-long MSIF with a core diameter of 1 mm (Thorlabs, Model BFL37-1000) was measured as a function of pulse duration, as shown in Fig. 2. The observed power-law dependence of energy on pulse duration for damage of the MSIF is similar to that found for damage of bulk material (Wood 1986; Stuart et al. 1995, 1996). These measurements show that although the energy threshold for damage with a 150-ps pulse is approximately a factor-of-three less than that with an 8-ns pulse, this energy is still significantly higher than that required for CARS spectroscopy with a 150-ps pulse in high-temperature flames (Meyer et al. 2007), as shown in Fig. 2a. On the contrary, even though a relatively high-energy threshold for damage is observed with an 8-ns pulse, this energy is not sufficient for acquiring good quality single-shot spectra (typically, SNR ~ 50) at high temperatures because of the reduction in peak power with longer pulses. This is illustrated in Fig. 2b, where the damage threshold is plotted in terms of peak power rather than laser energy. In this case, the transmitted power of the 150-ps pulse through the fiber is actually increased by 20-fold compared to that of an 8-ns pulse without causing fiber damage. The experimentally determined maximum transmission and the corresponding efficiency for two MSIFs are given in Table 1. It was found that using ns pulses, only the largest core-size fiber (1,500 μm) is capable of delivering pulse energies over the minimum energy required for CARS (Kuehner et al. 2003).

Laser-induced damage threshold at 532 nm for silica fiber as function of pulse duration. a Open circles represent measured energy threshold for damage, and diamonds represent required energy for performing single-shot CARS at flame temperature of 2,400 K. The corresponding power of a is shown in b. Dashed lines represent curve fitting

For the purpose of estimating the CARS signal, let us assume that all three input lasers are operating at the maximum threshold intensity I max that can propagate through the fiber without damage. Since the CARS signal strength is proportional to the product of intensities of pump, Stokes and probe pulses, it is reasonable to estimate the relative strength of the ps and ns fiber-based CARS signals, S ps-CARS and S ns-CARS, respectively, as being proportional to (I max)3. Since I max ~ (E out/τA), then the measured data in Table 1 show that S ps-CARS is ~500 times higher than S ns-CARS for the same cross-sectional area, A, of the laser beams at the focal point. Therefore, a substantially higher CARS signal can be expected using lasers with pulse widths of the order of 150 ps. Thus, based on the results shown in Table 1, the delivery of ps pulse energy not only sufficiently meets the requirements for generating robust CARS signals but also exceeds the optimal energy required for reacting-flow measurements. Therefore, from the damage-threshold point of view, ps laser-based fiber delivery is more favorable than ns laser-based delivery for obtaining a large signal for a fiber-based CARS system.

Employing ps lasers for CARS also has the advantage of enabling non-resonant background suppression (NRB) with minimal loss in signal, which is important for fiber-based CARS systems that will be photon-limited. In a ns-laser-based CARS approach, the pump, Stokes, and probe beams overlap temporally to produce a significant NRB signal. The interference of the NRB signal with the resonant CARS signal is one of the major disadvantages that limit the applicability, sensitivity, and accuracy of ns-CARS at higher pressure–especially in hydrocarbon-rich environments (Meyer et al. 2007; Seeger et al. 2009; Roy et al. 2010). On the contrary, in the ps-CARS regime, it is possible to delay the probe beam temporally with respect to the pump and Stokes beams for suppressing the non-resonant contribution to the CARS signal, thereby improving the sensitivity and accuracy of CARS thermometry (Roy et al. 2005b, 2010; Meyer et al. 2007). Although beyond the scope of the current work, the ability to separate the probe pulse from the pump and Stokes pulses also allows ps-CARS to be used for studies of energy transfer processes by performing time-resolved measurements where the probe beam interacts with the coherence during various phases of its evolution (Roy et al. 2005b, 2010; Meyer et al. 2007; Seeger et al. 2009; Kulatilaka et al. 2010).

4 Results: characterization of various fibers for CARS

Ideally, a fiber-based CARS system needs to have sufficient energy/irradiance such that a CARS signal with reasonable SNR can be generated without fiber damage, with minimal beam profile distortion (i.e., with a smaller beam-quality factor M 2). Therefore, the beams can be focused well at the probe volume, with minimal nonlinearity such that the bandwidth of the input laser does not change significantly, and with minimal dispersion of the beam so that the pulse duration is retained. Keeping these criteria in mind, the fiber characteristics for various ps and ns pulses through MSIFs were investigated in detail. For a 8-ns beam, the laser irradiance that could be delivered through a 1-mm-core-diameter silica fiber without damaging is ~0.2 GW/cm2, while it is ~3.3 GW/cm2 for a 100-ps laser beam. The corresponding energies are 12 and 4 mJ/pulse for ns and ps laser beams, respectively. Based on our experience and the results of other researchers involved in performing high-quality single-shot CARS measurement in a practical combustor, with a focal spot diameter of ~100 μm and an interaction length of ~1.5 mm, it was observed that the optimal energy for a 8- to 10-ns laser-based experiment is ~25 mJ/pulse and for a 100- to 120-ps laser-based experiment is ~0.5 mJ/pulse. Clearly, one needs to operate near the threshold of damage for fiber-based ns-CARS experiments, whereas the ps-CARS signal can be obtained well below the damage threshold of the fibers. Also, the advantages and disadvantages of using other fibers such as SMFs, fiber bundles of many SMFs, and state-of-the-art dispersion-compensated PCFs for a fiber-based CARS system were evaluated. Note that this study does not include comprehensive analysis of hollow-core fiber (HCF) because this type of fiber is very sensitive to bending losses; the bending losses of HCFs are ~2 dB/m at a bending radius of 30 cm (Robinson and Ilev 2004), which is approximately two to three orders of magnitude higher than those of solid-core fibers (Boechat et al. 1991). Since this investigation targeted production-level devices with limited optical access, these features were deemed problematic. However, with further advances in fiber-optic technology, evaluation of HCFs may be of significant future interest. Recently, Kriesel et al. investigated the feasibility of high-power laser-beam delivery through HCFs for CARS application (Kriesel et al. 2010). The transmission loss in HCF is ~1 dB/m (J. M. Kriesel, private communication) when compared to ~0.004 dB/m in our MSIF. However, the effect of bending on transmission loss in HCFs was not discussed in (Kriesel et al. 2010)

4.1 Investigation of damage threshold

As discussed earlier, sufficient pulse energy must be delivered at the probe volume of the sample to ensure generation of a CARS signal with reasonable SNR. To a large degree, this is dependent upon the damage threshold of the fiber. In Table 2, the damage threshold and the corresponding beam-quality factor M 2 are given for various fibers with 150-ps pulses for the frequency-doubled Nd:YAG wavelength of 532 nm, which is commonly used in many CARS systems and is available commercially in both the ns and ps regimes. Also given are the delivered output energy and the corresponding coupling efficiency for fibers of various sizes and constructions. In general, fibers with larger core diameters exhibited slightly higher coupling efficiency in MSIFs because of more effective mode coupling. The damage threshold of all-silica MSIFs (in which both the cladding and the core are made of silica) is approximately a factor-of-two higher than that of conventional MSIFs because the silica cladding has higher heat and radiation resistance than the non-silica cladding used in conventional MSIFs (Poli et al. 2007). The damage threshold of a single-mode fiber (SMF) is very low due to small core diameter. However, fiber bundles have a relatively high damage threshold. The solid-core LMA-PCFs exhibited the highest damage threshold when compared to conventional silica fibers. The damage threshold for the 150-ps laser pulse transmitted through a LMA-PCF is ~2.25 J/cm2, which is approximately a factor-of-five higher than that for MSIFs. The damage threshold of PCFs is higher than that of conventional fibers such as MSIFs because (1) the existence of a 2D photonic bandgap in the transverse direction guides the field propagating through the PCF without surface confinement, reducing the optical depth and, hence, increasing the damage threshold (Knight et al. 1998; Russell 2003, 2006) and (2) since the PCF is made of pure silica glass, the all-silica fiber exhibits better radiation and heat resistance than the conventional fiber (Poli et al. 2007). However, the transmission efficiency in PCFs is low, which can be attributed, in part, to inefficient coupling of the input laser beam to the relatively small core (diameter ~ 15 μm) and very small numerical aperture (NA) (NA ~ 0.04) of the PCF. It is well known that the optical damage threshold is low for bent fibers because of the intense light strip from the core into the clad, where it can be absorbed by the coating, which results in heating the coating and damaging the cladding (Percival et al. 2000; Glaesemann et al. 2006; Sun et al. 2007). Therefore, the effect of bending on the lowering damage threshold is important when the fiber is tightly bent (Sun et al. 2007). The effect of bending on the damage threshold of MSIFs and the fiber CARS signal will be investigated in our future work. In our experience, the bending loss is negligible for a 5-m-long MSIF fiber with a core diameter of 1 mm at 0.025 m bending radius (loss < 1%).

4.2 Propagation-related characteristics of fibers

Since laser beam properties can be modified during propagation through a fiber, a few other parameters that are of importance for a fiber-based CARS system are as follows: quality of the output beam at the exit of the fiber, energy/irradiance stability of the delivered beam, spectral broadening due to possible nonlinearities experienced by the intense laser pulses, and possible temporal broadening of the pulses. All such propagation-related changes were studied for different types of fibers. However, as will be discussed in the next subsection, MSIFs showed the most potential and, hence, were chosen for the experiment to be discussed in Sect. 5.

4.2.1 MSIFs with large core

Currently, two types of widely available large-core commercial fibers have the potential to deliver the intense laser beams necessary for CARS measurements in reacting flows—large HCFs and large solid-core MSIFs. HCFs are made of a glass capillary tube with an internal reflective coating and suffer higher loss due to Fresnel reflection (Parry et al. 2006). However, the absence of a solid core enables a higher damage threshold. Because of the significant transmission loss and degradation in beam quality during propagation through the fiber, the typical operational length of HCFs is limited to <2 m (Stephens et al. 2005). Furthermore, HCFs cannot withstand significant bend radii since this further degrades beam transmission and quality. For the state-of-the-art coated HCFs (Matsuura et al. 2002), the bending loss at 0.3 m bending radius was 2.3 dB, which is two to three orders of magnitude larger than that for commercial MSIF (~0.005 dB) (Boechat et al. 1991; Kovacevic and Nikezic 2006). Thus, such fibers are not suitable for applications involving high-power laser-beam delivery over a long distance and within enclosed test sections with complex geometries. On the contrary, solid-core MSIFs have a high transmission efficiency of greater than 70% and maintain the same beam quality over the entire length of the fiber (if the fiber is not bent) even though they have a lower damage threshold than HCFs because of stronger laser-material interaction in the solid core (Parry et al. 2006). Since large solid-core MSIFs are readily available commercially and are suitable for robust operations in harsh environments, they are the primary focus of the current study on laser transmission.

4.2.1.1 Output laser-beam quality

The spatial resolution of a CARS system is determined by the beam quality of the input laser at the probe volume. Using MSIFs, a top-hat beam profile can be obtained; however, the irradiance distribution still exhibits random variation in some areas that may appear as high-order modes or speckle, as shown in Fig. 3a. The spatial uniformity of the beam profile can be improved by coupling the laser beam into a larger core-size fiber where the number of guiding modes propagating through the fiber increases, as shown in Fig. 3b. However, an increase in the core size of the fiber results in an increase in M 2, as shown in Table 2, which degrades the ability to collimate and focus the beam. This can be partially addressed using a tapered fiber at the exit to improve the collimation of the output beam. It has also been reported that conditioning the beam before launching using a diffuser and ensuring that the focal point occurs in front of the fiber can effectively increase the damage threshold (Allison et al. 1985; Hand et al. 1999). These strategies are currently being investigated and will be reported in the future.

4.2.1.2 Stability measurements

As in any CARS-based system, the energy/irradiance stability of the input beam is essential for accuracy and precision. To examine the effects of fiber transmission on laser-beam stability, the power fluctuation of a 1-mJ pulse was measured over time for the beams entering and exiting a 1,500-μm-core-diameter MSIF, as shown in Fig. 4. Measurement results show that the average fluctuation of the laser beam through the fiber is ~40% lower than that of the original laser source. Thus, through fiber coupling, the signal fluctuations due to instrument noise can be reduced.

4.2.1.3 Spectral broadening

One of the important characteristics of fiber delivery systems is that nonlinearity increases with input laser irradiance. This behavior is of high interest in the current study because, as noted earlier, delivery of high-irradiance beams is essential for fiber-based CARS systems. The most visible signature of fiber nonlinearity is spectral broadening, which originates from nonlinear effects such as self-phase modulation and Raman effects under high laser-fluence conditions with strong dependency on the length of the fiber (Stolen and Lin 1978; Agrawal 2001; Boyd 2003). Spectral broadening for various lengths of MSIFs is shown in Fig. 5a. High peak-power ps pulse delivery can not only cause spectral broadening but also generates new frequencies due to the aforementioned nonlinearities. An additional new frequency of 85 cm−1 was generated for a ps pulse propagating through a 5-m fiber at a fluence of 204 mJ/cm2. These secondary frequencies may have the potential to reduce the spectral resolution of the CARS signal. In Fig. 5b, the power spectrum obtained using a ns laser pulse (with five times the energy of a ps pulse) shows that the power broadening and the bandwidth of additional frequencies generated through these nonlinear processes are approximately a factor-of-two lower than those obtained using a ps laser. From Fig. 5, it is clear that ps laser pulses lead to larger nonlinear effects than ns laser pulses because of the large peak intensities of the former.

a Measured power spectra for 150-ps laser-beam propagating through 1-m (dashed line, green), 3-m (dashed line, red), and 5-m-long (dashed line, blue) fiber at constant laser fluence (204 mJ/cm2). Spectra for low laser fluence (<1 mJ/cm2) are same for each length and are shown as black solid line. b Measured power spectra for 8-ns laser beam propagating through a 3-m-long fiber at high fluence of 1,020 mJ/cm2 (dashed line, red) and low fluence of <1 mJ/cm2 (solid line, black)

For exploring the fine structure of the power spectra, a high-resolution spectrometer (Jobin Yuvon, Model SPEX 1250M) was used to record the spectra at the exit of the fiber. The effects of laser fluence on the spectral profile of the transmitted 150-ps laser beam propagating through a 1-m fiber are presented in Fig. 6. The linewidth of the spectrum is broadened by approximately a factor-of-two when the fluence is increased from 18 to 72 mJ/cm2, illustrating that nonlinear effects can be significant in the transmission of a ps pulse through a MSIF.

4.2.1.4 Temporal broadening

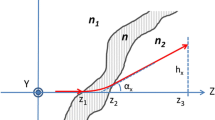

In addition to spectral broadening, the pulse can also be broadened temporally during its propagation through the fiber because of dispersion within the fiber. Such temporal broadening is strongly dependent on the fiber length, the laser wavelength, and the laser bandwidth. The temporal broadening of a pulse traveling in a dispersive medium can be theoretically calculated as (Agrawal 2001)

where σ(L) is the output pulse duration, σ0 is the input pulse duration, L is the fiber length, β is the dispersion characteristic parameter of the medium [for fused silica β = 700 fs2/cm at 532 nm (Agrawal 2001)], and ωd is the spectral bandwidth of the input pulse. For transform-limited 8-ns and 150-ps pulses delivered through a 20-m-long silica fiber, the pulse broadening is calculated to be negligible (<0.01%). Therefore, fiber delivery does not have a significant effect on the temporal profile distortion of ns and ps pulses for fiber lengths generally required for test-cell operations. On the contrary, temporal broadening is significant for fs pulses propagating through fiber because of the broad bandwidth. For example, for a transform-limited 100-fs pulse propagating through a 20-m-long silica fiber, the pulse broadening is calculated to be 14 ps, which is more than 140 times the input pulse duration. Hence, unlike ns and ps lasers, the use of fs lasers for fiber-based CARS system would require significant pre-compensation.

To summarize Sect. 4.2.1, the advantages of using MSIFs for delivery of ps laser pulses include a top-hat output beam profile, commercially available large-core MSIFs for transmission of high-irradiance laser beams, reduced instrumental noise, and minimal dispersion over long fiber lengths. The disadvantages include reduced spatial resolution due to poor beam quality (M 2 ≫ 1), which limits the beam-focusing ability, and significant nonlinear effects for longer length fibers.

Continuing with the feasibility study for a fiber-based CARS system, the characteristics of several other types of fibers for high-power laser-beam propagation were investigated, and the results are briefly summarized in the following section.

4.2.2 Single-mode graded-index fiber (SMF)

SMFs have an advantage over MSIFs in that they exhibit higher output beam quality [Gaussian profile and M 2 ~ 1 shown in Fig. 7a and Table 2, respectively] with a clean spatial mode. However, the main drawback of this fiber is that only a limited amount of energy can be transmitted through it, as shown in Table 2. It was observed that the maximum transmitted energy for a ps pulse was <2 μJ because of the small core size (core diameter ~ 3.5 μm). This is the case for both polarization-maintaining (Nufern, Model PM-460-HP) and non-polarization-maintaining (Nufern, Model 460-HP) fibers. Although it may be possible to improve the transmission efficiency through the use of a larger core diameter, the expected increase is probably insufficient for CARS spectroscopy in reacting flows.

4.2.3 Fiber bundles

Fiber bundles, which can be constructed by assembling a large group of SMFs, have been widely used for high-power laser-beam transmission and for multichannel imaging transmission (Anderson et al. 1996; Estevadeordal et al. 2005). In the present research effort, damage thresholds for various sizes of fiber bundles were investigated using 150-ps pulses at a visible wavelength of 532 nm. The results are included in Table 2. The fiber bundles (Myriad Fiber Imaging Tech, Inc.) can deliver >2.5 mJ/pulse with the smallest core size (FIGH-10-500N, a bundle of 10,000 SMFs with an estimated core size of 450 μm). The largest fiber bundle tested (FIGH-30-850N, a bundle of 30,000 SMFs with an estimated core size of 780 μm) can deliver >4 mJ/pulse. The beam profiles after transmission through the fiber bundles are shown in Fig. 7b. The output beam exhibits a diffused Gaussian beam profile due to leakage of light through the relatively thin cladding layer. It was observed that the small fiber bundles provide the highest output beam quality.

Fiber bundles are known to have excellent heat and radiation resistance. Other advantages observed in characterizing fiber bundles for fiber-based CARS include a higher damage threshold (typically three times higher than that of MSIFs). However, fiber bundles are likely to be unsuitable for fiber-based CARS because of a diffused Gaussian beam profile, low coupling efficiency, difficulty in coupling light uniformly into each SMF (Hand et al. 1999), and possible reduction in spatial resolution because of poor beam quality (M 2 ≫ 1).

4.2.4 PCFs

PCFs have attracted widespread attention because of their configurable dispersion properties when compared to those of standard fibers (Russell 2003, 2006; Zolla et al. 2005). In particular, high peak-power transmission (Borghesi et al. 1998; Shephard et al. 2004; Konorov et al. 2004), low optical loss (Smith et al. 2003; Roberts et al. 2005; Kristensen et al. 2008), and high-quality beam profiles (Shephard et al. 2006) are achievable with PCFs (Knight et al. 1998; Cregan et al. 1999; Russell 2003, 2006).

In our experiment, a 1-m-long solid-core LMA-PCF with 15-μm core diameter and optimized for maximum transmission at 532 nm was used. The output beam profile presented in Fig. 7c displays the high-quality Gaussian profile that was obtained at the exit of the PCF. As noted earlier, PCFs have higher damage threshold irradiance than conventional fibers. Moreover, the effect of nonlinear spectral broadening in PCFs is small compared to that in MSIF, as shown in Fig. 8. These observations suggest that the spectral resolution and image contrast of fiber-based CARS can be improved through the use of PCFs. However, only a limited amount of energy can be delivered through a solid-core PCF because of its small core size; hence, the output power is insufficient for performing fiber-based CARS in reacting flows. Nevertheless, with the advent of specially designed, air-guided hollow-core PCFs at the desired wavelengths, it may be possible to transmit sufficient energy with low nonlinearity and high beam quality for gas-phase CARS spectroscopy. Because of the absence of a solid glass core and the reduced overlap between the glass and the light, hollow-core PCFs can have smaller core diameters with much higher optical damage thresholds than MSIFs and solid-core PCFs (Borghesi et al. 1998; Shephard et al. 2004; Russell 2003, 2006; Konorov et al. 2004). However, the major drawback of hollow-core PCFs is the significant cost associated with the production of each custom-designed fiber at the desired wavelength because PCF manufacturing techniques are still evolving.

However, if hollow-core PCFs become more readily available, their advantages over standard MSIFs for fiber-based CARS would include higher damage threshold due to the photonic band-gap guiding mechanism, negligible nonlinear effects, manipulation of the zero-dispersion point, good spatial-mode filter, and low transmission loss over long distances (~2 dB/Km) (Roberts et al. 2005).

4.3 Summary of fiber characterizations

The study of various fiber characteristics will now be summarized (see Table 3). MSIFs and fiber bundles have the combination of higher damage threshold and large core size needed for fiber-based delivery of intense laser pulses for performing CARS in reacting flows. The low transmission loss also enables remote operation of the laser system for isolation from harsh environments. SMFs are preferable for delivering a high-quality beam profile but are incapable of delivering high-energy laser pulses. The main disadvantages of MSIFs are generally nonlinear effects and limited focusing ability. In contrast, PCFs have a high-quality spatial beam profile, low dispersion, low transmission loss, and a high damage threshold. Unfortunately, the low coupling efficiency and lack of commercial availability limits the usefulness of this fiber at this time. Hence, in terms of overall performance for a fiber-based CARS system, MSIFs or fiber bundles are currently considered to be the most suitable for delivery of high-irradiance ps pulses. Since MSIFs can be constructed with all-silica materials (core and cladding), it is possible to increase the damage threshold and delivered laser energy when compared to traditional MSIFs while improving the spatial mode significantly. Hence, ps-CARS demonstration measurements were conducted using all-silica MSIFs, as detailed further below.

5 Fiber-based ps-CARS experiments

Based on studies described earlier for delivering intense laser pulses through optical fibers for CARS spectroscopy, a proof-of-principle, fiber-based ps-N2-CARS system employing MSIFs was developed for gas-phase thermometry, as shown in Fig. 9. For this proof-of-principle experiment, the CARS system was designed using a collinear phase-matching geometry because of its higher signal strength and ease of alignment. The 532-nm output of a frequency-doubled, 10-Hz, Nd:YAG regenerative amplifier was used for the pump beam in the fiber-based CARS system. The ~607-nm output of a home-built modeless dye laser pumped by the same Nd:YAG laser was used as the Stokes beam (Roy et al. 2005a). The output of the dye laser has a full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) bandwidth of ~135 cm−1 and a pulse duration of ~115 ps. The Nd:YAG output is a nearly transform-limited beam at 532 nm and has a FWHM pulse duration of ~135 ps. Note that the same 532-nm beam serves as both the “pump” and “probe” beams in the collinear CARS configuration. The pump and Stokes beams were coupled into two 30-cm-long all-silica MSIFs (OFS, Model HCG-M0500T), each having a 550-μm core diameter. To avoid damaging the fibers at high pulse energies while maintaining good coupling efficiency, each fiber was installed behind the focal point of the coupling lens (Allison et al. 1985; Hand et al. 1999). The fiber-delivered pump and Stokes energies at the probe volume were 1.6 mJ for each beam. The two fiber-delivered beams were combined to propagate collinearly using a dichroic mirror and were focused into the probe volume. The beam diameter and the divergence of each beam were adjusted independently for spatially overlapping the focal points of the two beams. The focal spot size was reduced to 100 μm by allowing the two beams that exit the fiber to diverge slightly such that they nearly fill the clear aperture of a 50-mm-diameter focusing lens. A delay line in the pump–beam line was used to overlap the pump and Stokes pulses temporally. The collected CARS signal was dispersed by a 1.25-m spectrometer (Jobin Yuvon, Model SPEX 1250M) with a 2,400-grove/mm grating, and the spectrum was recorded using a back-illuminated, unintensified, 2,048 × 512-pixel-array CCD camera (Andor Technologies, Model DU 440BU). The overall dispersion was estimated to be ~0.174 cm−1/pixel. Measurements were performed in the product zone of an adiabatic H2-air flame stabilized over a Hencken burner at a height of 10 mm above the burner surface. The flame temperature was adjusted by changing the equivalence ratio (ϕ) of the flame, defined as the actual fuel-to-air ratio to the stoichiometric fuel-to-air ratio.

Figure 10 shows N2 spectra at various flame temperatures that were acquired using the fiber-based ps-CARS system. These spectra are plotted using the square root of the signal intensity, which is proportional to the N2 number density in the medium. Moreover, to increase the SNR for the fitting process, each spectrum was averaged over 5,000 laser pulses. Figure 10 shows a comparison with the theoretical spectra obtained by the Sandia CARSFT code (Palmer 1989). The temperature can be extracted from the CARS spectra by fitting the intensity and bandwidth of the primary band (ν = 0 → ν = 1) and the first hot band (ν = 1 → ν = 2) of N2. The extracted temperature and spectra obtained by CARSFT agree well with experimental room-air CARS results, as presented in Fig. 10a. However, in Fig. 10b–d, the temperature obtained by CARSFT is lower than the adiabatic flame temperature by 60–450 K for ϕ = 0.18 to ϕ = 0.71, respectively. To verify that the fiber delivery is not the main cause of the difference between the temperature extracted by CARSFT and the adiabatic flame temperature, direct-beam (without fibers) collinear CARS measurements were also performed under the same flame conditions. The temperature acquired from direct-beam CARS measurements agrees well with that from fiber-based CARS, as shown in Fig. 11. The measured temperature difference for the two cases is <±2%, which is within the standard temperature resolution of CARS measurements. The observed temperature bias may result from the collinear configuration used in the experiments, in which non-negligible contributions to the N2 CARS signal can be generated from the cooler regions. Hence, the measured CARS spectrum is composed of spatially averaged CARS signals from high- and low-temperature regions along the beam propagation path. The temperature bias, resulting from the collinear geometry, becomes significant as the flame temperature increases further, limiting the temperature accuracy of the current system for high-temperature flame measurements (Thumann et al. 1995; Eckbreth 1996; Seeger et al. 2006). However, this temperature bias can be greatly reduced through the use of the well-known folded BOXCARS geometry, in which the CARS signal is generated only at the probe volume where all beams overlap spatially. By employing the folded BOXCARS geometry, the spatial resolution of the temperature measurements can be greatly improved (Eckbreth 1996). In addition, when a dedicated probe beam is added in the BOXCARS geometry, it enables an increase in the CARS signal and suppression of NRB by temporally delaying the probe pulses (Roy et al. 2005b; Meyer et al. 2007). We are currently working with various fiber manufacturers to design and fabricate fiber collimators with beam-shaping telescopes for large-core MSIFs to perform fiber-based CARS in BOXCARS geometry for combustion diagnostic applications.

6 Summary

The feasibility of delivering intense laser pulses through optical fibers for CARS spectroscopy was investigated. It was demonstrated that the propagation of ps laser pulses through large-core MSIFs allows transmission of sufficient laser energy for performing CARS thermometry in reacting flows. It was also determined experimentally that the use of ps pulses would provide significantly larger CARS signal without damaging the fiber. The transmission characteristics of ps pulses through MSIFs were investigated in great detail. Other fibers such as SMFs, fiber bundles, and state-of-the-art dispersion-compensated PCFs were also studied as potential candidates for a fiber-based CARS system. Based on the fiber characteristics studies, it was concluded that all-silica MSIFs are currently the most suitable fibers for fiber-based CARS. Although hollow-core PCFs appeared to have high potential for fiber-based nonlinear spectroscopy techniques, their major shortcomings are the significant cost associated with the production of each fiber for a specific wavelength.

A proof-of-principle, fiber-based ps N2 CARS system employing MSIFs has been developed and demonstrated for gas-phase thermometry in flames. It has been demonstrated experimentally that the temperatures measured using fiber-based CARS agree well with those from direct-beam CARS measurements, and the difference between the two cases is within ±2%. The proof-of-concept measurements show significant promise for extending the application of fiber-based CARS measurements to the harsh environments of combustors and engine test facilities. The use of ps-CARS also enables reduction in non-resonant background without significant loss in signal, which is important for maintaining sufficient SNR in the hot-band spectra for combustion thermometry. Future work includes measurements using the BOXCARS phase-matching geometry for improving spatial resolution and tests with longer fibers for characterizing the effects of spectral broadening.

References

Agrawal GP (2001) Nonlinear fiber optics, 3rd edn. Academic Press, San Diego

Allison SW, Gillies GT, Magnuson DW, Pagano TS (1985) Pulsed laser damage to optical fibers. Appl Opt 24:3140–3145

Andersen ER, Nielsen CK, Thogersen J, Keiding SR (2007) Fiber laser-based light source for coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microspectroscopy. Opt Express 15:4848–4856

Anderson DJ, Morgan RD, McCluskey RD, Jones JDC, Easson WJ, Greated CA (1995) An optical fibre delivery system for pulsed laser particle image velocimetry illumination. Meas Sci Technol 6:809–814

Anderson DJ, Jones JDC, Easson WJ, Greated CA (1996) Fiber-optic-bundle delivery system for high peak power laser particle image velocimetry illumination. Rev Sci Instrum 67:2675–2679

Boechat AAP, Su D, Hall DR, Jones JDC (1991) Bend loss in large core multimode optical fiber beam delivery systems. Appl Opt 30:321–327

Borghesi M, Mackinnon AJ, Gaillard R, Willi O, Offenberger AA (1998) Guiding of a 10-TW picosecond laser pulse through hollow capillary tubes. Phys Rev E 57:R4899–R4902

Boyd RW (2003) Nonlinear optics. Elsevier, Singapore

Campbell JH, Rainer F, Kozlowski MR, Wolfe CR, Thomas IM, Milanovich FP (1990) Damage resistant optics for a mega-joule solid-state laser. Proc SPIE 1441:444–456

Champagne Y, Bélanger PA (1995) Method for measurement of realistic second-moment propagation parameters for nonideal laser beams. Opt Quan Electron 27:813–824

Cregan RF, Mangan BJ, Knight JC, Birks TA, Russell PSJ, Roberts PJ, Allan DC (1999) Single-mode photonic band gap guidance of light in air. Science 285:1537–1539

Du D, Liu X, Mourou G (1996) Reduction of multi-photon ionization in dielectrics due to collisions. Appl Phys B 63:617–621

Eckbreth AC (1996) Laser diagnostics for combustion temperature and species, 2nd edn. Gordon and Breach, Netherlands

Estevadeordal J, Meyer TR, Gogineni SP, Polanka MD, Gord JR (2005) Development of a fiber-optics PIV system for turbomachinery application. AIAA Paper 2005-0038

Fischer RE, Tadic-Galeb B, Yoder PR Jr (2008) Optical system design, 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Glaesemann GS, Winningham MJ, Clark DA, Coon J, DeMartino SE, Logunov SL, Chien CK (2006) Mechanical failure of bent optical fiber subjected to high power. J Am Ceram Soc 89:50–56

Gord JR, Meyer TR, Roy S (2008) Applications of ultrafast lasers for optical measurements in combusting flows. Ann Rev Anal Chem 1:663–687

Gord JR, Hsu PS, Patnaik AK, Meyer TR, Roy S (2009) Gas-phase temperature measurements in reacting flows using fiber-coupled picosecond coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering spectroscopy. AIAA Paper 2009-1444

Hahn JW, Park CW, Park SN (1997) Broadband coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy with a modeless dye laser. Appl Opt 36:6722–6728

Hand DP, Entwistle JD, Maier RR, Kuhn A, Greated CA, Jones JDC (1999) Fibre optic beam delivery system for high peak power laser PIV illumination. Meas Sci Technol 10:239–245

Harjes HC (1979) Laser triggered spark gap using fiber optics transmission. Sci Rep 1 on LLL Subcon 2257509, Texas Tech University

Hsu PS, Kulatilaka WD, Patnaik AK, Gord JR, Roy S (2010) Picosecond laser-based fiber-coupled CARS spectroscopy for gas-phase thermometry. AIAA paper 2010-1399

Knight JC, Broeng J, Birks TA, Russell PSJ (1998) Photonic band gap guidance in optical fibers. Science 282:1476–1478

Konorov SO, Mitrokhin VP, Fedotov AB, Sidorov-Biryukov DA, Beloglazov VI, Skibina NB, Wintner E, Scalora M, Zheltikov AM (2004) Hollow-core photonic-crystal fibres for laser dentistry. Phys Med Biol 49:1359–1368

Kovacevic MS, Nikezic D (2006) Influence of bending on power distribution in step-index plastic optical fibers and the calculation of bending loss. Appl Opt 45:6675–6681

Kriesel JM, Gat N, Plemmons D (2010) Fiber optics for remote delivery of high power pulsed laser beams. AIAA paper 2010-1305

Kristensen JT, Houmann A, Liu XM, Turchinovich D (2008) Low-loss polarization-maintaining fusion splicing of single-mode fibers and hollow-core photonic crystal fibers, relevant for monolithic fiber laser pulse compression. Opt Express 16:9986–9995

Kuehner JP, Woodmansee MA, Lucht RP, Dutton JC (2003) High-resolution broadband N2 coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy: comparison of measurements for conventional and modeless broadband dye lasers. Appl Opt 42:6757–6767

Kulatilaka WD, Hsu PS, Stauffer HU, Gord JR, Roy S (2010) Direct measurement of rotationally resolved H2 Q-branch Raman coherence lifetime using time-resolved picosecond coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering. Appl Phys Lett 97:1

Légaré F, Evans CL, Ganikhanov F, Xie XS (2006) Towards CARS endoscopy. Opt Express 14:4427–4432

Lowdermilk WH, Milam D (1981) Laser-induced surface and coating damage. IEEE J Quant Electron 17:1888–1903

Lowdermilk WH, Milam D (1984) Review of ultraviolet damage threshold measurements at Lawrence Livemore National Laboratory. Proc SPIE 476:143–162

Mann G, Vogel J, Preuß R, Vaziri P, Zoheidi M, Eberstein M, Krüger J (2007) Nanosecond laser damage resistance of differently prepared semi-finished parts of optical multimode fibers. Appl Surf Sci 254:1096–1100

Marangoni M, Gambetta A, Manzoni C, Kumar V, Ramponi R, Cerullo G (2009) Fiber-format CARS spectroscopy by spectral comparison of femtosecond pulses from a single laser oscillator. Opt Lett 34:3262–3264

Matsuura Y, Takada G, Yamamoto T, Shi YW, Miyagi M (2002) Hollow fiber for delivery of harmonic pulses of Q-switched Nd:YAG lasers. Appl Opt 41:442–445

Merkle LD, Koumvakalis N, Bass M (1984) Laser-induced bulk damage in SiO2 at 1.064, 0.532, and 0.355 μm. J Appl Phys 55:772–775

Meyer TR, Roy S, Gord JR (2007) Improving signal-to-interference ratio in rich hydrocarbon-air flames using picosecond coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering. Appl Spectrosc 61:1135–1140

Murugkar S, Brideau C, Ridsdale A, Naji M, Stys PK, Anis H (2007) Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy using photonic crystal fiber with two closely lying zero dispersion wavelengths. Opt Express 15:14028–14037

Palmer RE (1989) The CARSFT computer code for calculating coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectra: user and programmer information. Report SAND89-8206. Sandia National Laboratories, Livermore, CA

Parry JP, Stephens TJ, Shephard JD, Jones JDC, Hand DP (2006) Analysis of optical damage mechanisms in hollow-core waveguides delivering nanosecond pulses from a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. Appl Opt 45:9160–9167

Percival RM, Sikora ESR, Wyatt R (2000) Catastrophic damage and accelerated ageing in bent fibers caused by high optical powers. Electron Lett 36:414–416

Pini R, Salimbeni R, Matera M, Lin C (1983) Wideband frequency-conversion in the UV by nine orders of stimulated Raman scattering in a XeCl laser pumped multimode silica fiber. Appl Phys Lett 43:517–518

Poli F, Cucinotta A, Selleri S (2007) Photonic crystal fibers: properties and applications. Springer, Netherlands

Pronko PP, VanRompay PA, Horvath C, Loesel F, Juhasz T, Liu X, Mourou G (1998) Avalanche ionization and dielectric breakdown in silicon with ultrafast laser pulses. Phy Rev B 58:2387–2390

Roberts PJ, Couny F, Sabert H, Mangan BJ, Williams DP, Farr L, Mason MW, Tomlinson A, Birks TA, Knight JC, Russell PSJ (2005) Ultimate low loss of hollow-core photonic crystal fibers. Opt Express 13:236–244

Robinson RA, Ilev IK (2004) Design and optimization of a flexible high-peak-power laser-to-fiber coupled illumination system used in digital particle image velocimetry. Rev Sci Instrum 75:4856–4862

Roy S, Meyer TR, Gord JR (2005a) Broadband coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering spectroscopy of nitrogen using a picosecond modeless dye laser. Opt Lett 30:3222–3224

Roy S, Meyer TR, Gord JR (2005b) Time-resolved dynamics of resonant and nonresonant broadband picosecond coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering signals. Appl Phys Lett 87:264103–264105

Roy S, Gord JR, Patnaik AK (2010) Recent advances in coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering spectroscopy: fundamental developments and applications in reacting flows. Prog Energy Combust Sci 36:280–306

Russell PSJ (2003) Photonic crystal fibers. Science 299:358–362

Russell PSJ (2006) Photonic-crystal fibers. J Lightwave Technol 24:4729–4749

Sasnett MW, Johnston TF (1991) Beam characterization and measurement of propagation attributes. Proc SPIE 1414:21–32

Seeger T, Weikl MC, Beyrau F, Leipertz A (2006) Identification of spatial averaging effect in vibrational CARS spectra. J Raman Spectrosc 37:641–646

Seeger T, Kiefer J, Leipertz A, Patterson BD, Kliewer CJ, Settersten TB (2009) Picosecond time-resolved pure rotational coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy for N2 thermometry. Opt Lett 34:3755–3757

Shen XA, Jones SC, Braunlich P (1989) Laser heating of free electrons in wide-gap optical materials at 1064 nm. Phys Rev Lett 62:2711–2713

Shephard JD, Jones JDC, Hand DP, Bouwmans G, Knight JC, Russell PStJ, Mangan BJ (2004) High energy nanosecond laser pulses delivered single-mode through hollow-core PBG fibers. Opt Express 12:717–723

Shephard JD, Roberts PJ, Jones JDC, Knight JC, Hand DP (2006) Measuring beam quality of hollow core photonic crystal fibers. J Lightwave Technol 24:3761–3769

Smith AV, Do BT (2008) Bulk and surface laser damage of silica by picosecond and nanosecond pulses at 1064 nm. Appl Opt 47:4812–4832

Smith CM, Venkataraman N, Gallagher MT, Müller D, West JA, Borrelli NF, Allan DC, Koch KW (2003) Low-loss hollow-core silica/air photonic bandgap fibre. Nature 424:657–659

Smith A, Do B, Schuster R, Collier D (2008) Rate equation model of bulk optical damage of silica, and the influence of polishing on surface optical damage of silica. Proc SPIE 6873:U118–U129

Smith AV, Do BT, Hadley GR, Farrow RL (2009) Optical damage limits to pulse energy from fibers. IEEE J Sel Top Quant Electron 15:153–158

Snelling DR, Sawchuk RA, Parameswaran T (1994) Noise in single-shot broadband coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy that employs a modeless dye laser. Appl Opt 33:8295–8301

Stephens TJ, Haste MJ, Parry JP, Towers DP, Matsuura Y, Shi YW, Miyagi M, Hand DP (2005) Hollow-core waveguides for particle image velocimetry. Meas Sci Technol 16:1119–1125

Stolen RH, Lin C (1978) Self-phase-modulation in silica optical fibers. Phys Rev A 17:1448–1453

Stuart BC, Feit MD, Rubenchik AM, Shore BW, Perry MD (1995) Laser-induced damage in dielectrics with nanosecond to subpicosecond pulses. Phys Rev Lett 74:2248–2251

Stuart BC, Feit MD, Herman S, Rubenchik AM, Shore BW, Perry MD (1996) Nanosecond-to-femtosecond laser induced breakdown in dielectric. Phys Rev B 53:1749–1761

Sun XG, Li J, Hokansson A (2007) Study of optical fiber damage under tight bend with high optical power at 2140 nm. In: Proceedings of SPIE, vol 6433, p 43309

Thumann A, Seeger T, Leipertz A (1995) Evaluation of two different gas temperatures and their volumetric fraction from broadband N2 coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy spectra. Appl Opt 34:3313–3317

Tien AC, Backus S, Kapteyn H, Murnane M, Mourou G (1999) Short-pulse laser damage in transparent materials as a function of pulse duration. Phys Rev Lett 82:3883–3886

Torruellas W, Chen Y, McIntosh B, Farroni J, Tankala K, Webster S, Hagan D, Soileau MJ, Messerly M, Dawson J (2006) High peak power ytterbium-doped fiber amplifiers. In: Proceedings of SPIE, vol 6102, pp 61020N-1–61020N-7

Wang H, Huff TB, Cheng JX (2006) Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering imaging with a laser source delivered by a photonic crystal fiber. Opt Lett 31:1417–1419

Wood RM (1986) Laser-induced damage of optical materials. Hilger, Boston

Zolla F, Renversez G, Nicolet A, Kuhlmey B, Guenneau S, Felbacq D (2005) Fundamentals of photonic crystal fibres. Imperial College Press, London

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge useful discussions with Prof. Thomas Seeger of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Prof. Margaret M. Murnane of the University of Colorado/JILA, and Dr. Hans Stauffer and Ms. Amy Lynch of the Air Force Research Laboratory. The authors thank Mr. Shuvro Roy for the help with the experimental setup. Funding for this research was provided by the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) under Contract Nos. FA9101-09-C-0031 and FA8650-09-C-2001 and by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (Dr. Julian Tishkoff and Dr. Tatjana Curcic, Program Managers).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Bulk, surface, and core–clad interface damage

Appendix: Bulk, surface, and core–clad interface damage

In the study of the transmission of high-power laser beams through a fiber, the three damage mechanisms that can cause optical damage in silica fibers are as follows: (1) bulk damage, (2) surface damage, and (3) core–clad interface damage. A summary of the damage thresholds via three damage mechanisms reported in the literature for fused silica in the ps and ns regime is presented in Table 4. As shown in the table, the damage threshold of all the above types of damages may vary by orders of magnitude, depending on many parameters defined by the experimental conditions such as the input laser-beam profile (laser modes), incident spot size and position, fiber-tip surface flatness, and laser wavelength. In this study, we do not claim to resolve such disagreements but only report the observed threshold for our own conditions of measurement and indicate agreements/disagreements with other reported studies.

The single-shot damage threshold for pure bulk fused silica reported by Du et al. was 80–250 J/cm2 using 7-ns pulses at a wavelength of 780 nm (Du et al. 1996). A similar result was obtained by Tien et al. (Tien et al. 1999). Campbell et al. reported a damage threshold of 50 J/cm2 using 7-ns pulses at 1,060 nm (Campbell et al. 1990). Merkle et al. reported a damage threshold for suprasil-1 fused silica of 1,400 J/cm2 using 15-ns pulses at 532 nm (Merkle et al. 1984). The multiple-shot damage threshold for bulk silica was reported by Stuart et al. to be 40 J/cm2 using 600-shot, 1-ns pulses at 1,053 nm (Stuart et al. 1995). Torruellas et al. reported a damage threshold of 800 J/cm2 for Yb-doped fused silica using 1,000-shot, 15-ns pulses at 1,064 nm (Torruellas et al. 2006). Smith and Do reported the damage threshold of polished bulk silica to be 3,800 J/cm2 using 8-ns pulses at 1,064 nm with a small focal spot size (results obtained for both single and multiple shots) (Smith and Do 2008). Smith and collaborators reported that the high damage threshold obtained may have resulted from the use of a small focal spot and single-longitudinal pulses to reduce the SBS and self-focusing effects (Smith and Do 2008; Smith et al. 2008, 2009).

The surface damage thresholds of fused silica were reported by Pini et al. to be 10 J/cm2 using 7.5-ns pulses at 308 nm (Pini et al. 1983). Lowdermilk and Milam reported a higher surface damage threshold for optically polished silica of 30–50 J/cm2 using 3-ns pulses at 1,064 nm (Lowdermilk and Milam 1981). Mann et al. reported the surface damage threshold of polished suprasil silica to be 150–320 J/cm2 using 1-ns pulses at 1,064 nm (Mann et al. 2007). Smith and Do showed that the surface damage threshold (3,800 J/cm2) could be made the same as the bulk damage threshold through the use of an alumina or silica surface polish (Smith and Do 2008). The core–clad interface damage for silica-core/plastic(hard)-clad fibers was reported by Allison et al. to be 0.7–6.4 J/cm2 using 5-ns pulses at 392 nm (Allison et al. 1985). Anderson et al. reported the interface damage for silica-core/silica-clad fibers to be 1.8–5.6 J/cm2 using 6-ns pulses at 532 nm (Anderson et al. 1995).

According to Table 4, clearly the damage threshold of the bulk is higher than that of the surface and of the core–clad interface. Harjes showed that laser-induced damage thresholds (LIDT) of the surface of the material are approximately one-third that of the bulk material (Harjes 1979). From Table 4, the reported damage threshold of the well-polished surface is higher than that of the core–clad interface. Allison et al. reported that the damage threshold of the core–clad interface is approximately one order of magnitude lower than that of the surface (Allison et al. 1985). From our fiber-damage test for the plastic-clad silica fiber (Thorlabs, Model BFL37-1000), the observed damage fluence for the fiber is in the range 1.5–2.1 J/cm2 (damage test parameters: τ = 8 ns, λ = 532 nm). The damage-threshold values obtained are in good agreement with those of Allison et al. (Allison et al. 1985).

Furthermore, according to Table 4, the lowest threshold of fluence at which the onset of fiber damage can occur is due to core–clad interface damage. The core–clad interface damages were observed from our damage test; the damage in the fiber appeared as a linear fracture along the core–clad interface, generally beginning within a few centimeters from the input fiber facet. Therefore, the lower LIDT for the fiber reported in our study is thought to result from the damage of the core–clad interface that has a threshold which is lower than that of the bulk and surface.

Table 4 is a summary of the damage thresholds reported in the literature for fused silica, corresponding to the mechanisms related to bulk damage, surface damage, and core–clad interface damage in the ns and ps regime.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hsu, P.S., Patnaik, A.K., Gord, J.R. et al. Investigation of optical fibers for coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) spectroscopy in reacting flows. Exp Fluids 49, 969–984 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-010-0961-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-010-0961-6