Abstract

We report on the fabrication of a crystalline multi-layer lutetium aluminium garnet planar waveguide, with a ytterbium-doped core, via hetero-epitaxial pulsed laser deposition on an undoped yttrium aluminium garnet substrate. Physical and optical characterization of the device revealed good crystallinity of the grown films and mode propagation investigations confirmed waveguiding properties. The measured fluorescence lifetime and calculated absorption and stimulated emission cross section spectra are found to be comparable with those reported for Yb:LuAG crystals grown by traditional methods. When end-pumped by a diode-laser bar, the crystalline double-clad Yb:LuAG planar waveguide lased using a quasi-monolithic cavity configuration. An output power of > 3 W with a 20% slope efficiency was obtained, limited by a waveguide propagation loss of 1.2 dB cm−1. This first demonstration of a multi-layer LuAG double-clad planar waveguide laser shows great potential for realising compact high-power waveguide lasers and amplifiers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The field of optically pumped planar waveguide lasers (PWL) has developed rapidly over the past few decades driven by the requirements of a range of applications, including optical communications, all-optical switching for signal processing, lab-on-chip integration, master oscillator power amplifier (MOPA) sources, remote sensing, ranging and spectroscopy [1, 2]. The planar waveguide (PW) gain-medium geometry, offering an intermediate configuration between the thin-slab and optical-fibre, possesses several attractive features, including the potential for high optical gain with effective thermal management. PWL are compatible with diode-laser pumping, leading to efficient operation as demonstrated with various Yb-doped materials, such as garnets [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10], double tungstates [11,12,13], fluorides [14] and glasses [15]. Recently, good progress has been realised in fabricating high-quality crystalline ytterbium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Yb:YAG) planar waveguides by the pulsed laser deposition (PLD) technique. Initial laser experiments demonstrated Watt-level output from PLD-grown Yb:YAG PWs in 2015 [16], and a fivefold increase in laser power was reported a year later with 11.5 W and a 48% slope efficiency [17]. Subsequent improvements lead to a 21 W PWL with 70% slope efficiency, and the first demonstration of a PLD-grown planar waveguide amplifier with a small-signal gain of 24 dB. A maximum of 31 W (2 dB gain), in the saturated regime, with a 55% extraction efficiency was also obtained [18].

For a double-clad PW design, where the core mode(s) interact with the outer-cladding interfaces [4], mode selection can be achieved via gain saturation effects through tailoring the doping profile [2, 19], which can be crucially important for power scaling PWL [20]. In many cases, simply restricting the doping to the central portion (< 60%) of the full waveguide aperture robustly selects fundamental-mode operation [2]. This allows non-diffraction-limited diode-laser-bar-pumping of the multi-mode PW with excellent efficiency.

The dominance of YAG as a crystal host for Yb3+ ions is due to many material advantages such as an isotropic structure, physical and chemical robustness, potential for high dopant-ion concentrations, broad absorption bands in spectral regions where diode-lasers are available, and a thermal conductivity of ~ 10 W/m K at low impurity levels [21, 22]. However, increasing the Yb3+ concentration reduces the crystal’s thermal conductivity, e.g. to 6.1 W/m K for 10at. % Yb3+ [21]. In contrast, despite comparable physical and chemical properties, the thermal conductivity of the Yb-doped Lu3Al5O12 (Yb:LuAG) crystal, while lower than its isomorph YAG, is not strongly affected by ytterbium content, i.e. it has a value of 7.7 W/m K for undoped LuAG and 7.4 W/m K for 10 at.% Yb3+ doping [21]. This is due to the small atomic mass difference between Yb3+ and Lu3+ in comparison to Y3+, leading to a lower phonon scattering rate and higher thermal conductivity.

Recently, a ceramic Yb:LuAG PWL was reported based upon a YAG/Yb(15 at.%):LuAG/YAG composite, with a 0.6 mm- thick active core [23]. The output power reported was 288 mW at 1030.7 nm, with a maximum slope efficiency of 9%. Here, for the first time to our knowledge, we report the fabrication of a double-clad Yb:LuAG planar waveguide comprising three LuAG layers, with the central layer doped with Yb3+ to make an active core and the undoped-cladding layers themselves bounded by the YAG-substrate and air interfaces. Initial PWL results produced 3.3 W output power and 20% slope efficiency for a 940-nm diode-laser end-pumped quasi-monolithic configuration. With additional optimisation of the fabrication process, via our recent bi-directional target ablation technique, [24], it will be possible to reduce the waveguide propagation losses further to enable more efficient laser performance, paving the way for power-scaling through pumping with diode-laser stacks [8].

2 Fabrication and material characterization

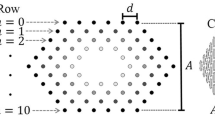

Designed to have a 7 at.% Yb-doped LuAG core layer bounded by two nearly refractive index-matched undoped LuAG cladding layers, and a core to full-waveguide thickness ratio of 0.5, the waveguide will provide a preferential selection of the fundamental propagating mode through gain saturation [2, 19].

The three layers were sequentially deposited on a 10 × 10 × 1 mm <100>-oriented YAG substrate using our PLD setup, shown in Fig. 1. A KrF excimer laser operating at a wavelength of 248 nm, with pulse duration of 20 ns, and a repetition rate of 100 Hz was focused to produce a fluence of ~ 1.1 J cm−2 on a LuAG or Yb:LuAG ceramic target. Each target was used sequentially for the respective undoped and doped layer depositions. The YAG substrate was heated to ~ 740 °C from the rear side, using a CO2 laser beam. The CO2 laser beam was shaped by a ZnSe tetra-prism, such that the profile matched the square substrate to provide quasi-uniform heating [25]. Deposition was conducted in an oxygen atmosphere at a pressure of 2 × 10−2 mbar, leading to an average growth rate for this material of ~ 5 µm/h, for both the doped and undoped layers.

Following the growth, two opposing facets of the waveguide structure were polished plane-parallel resulting in a final waveguide length of 9.5 ± 0.05 mm. A microscope image and backscatter scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of part of one facet is shown in Fig. 2a, b, respectively. Note the SEM image contrast has been enhanced to highlight the core. The central Yb:LuAG layer was ~ 4.0 μm-thick with each LuAG cladding layer ~ 2.0 μm-thick, yielding a total waveguide thickness of ~ 8.0 μm.

The waveguide fluorescence was imaged, as shown in Fig. 2c, obtained with a 20 × microscope objective mounted on a tube attached to a Spiricon SP620U beam-profiling camera. As the tube lens length was not identical to that of a microscope, this setup provided an object magnification of 17.7 times at the camera sensor. The Yb3+ ions in the waveguide were excited from the opposite facet by coupled light from a 974-nm fibre-coupled single-mode diode laser. Residual pump radiation was rejected before reaching the camera using a HR@915–980 nm, HT@1030 nm dichroic mirror. Figure 2c clearly demonstrates the waveguiding properties of the double-clad structure with no visible boundaries between LuAG and Yb:LuAG layers. A higher intensity—the orange band shown in Fig. 2c—is observed to be closer to the substrate, as this interface has the lower refractive index contrast.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed on the multilayer waveguide structure using a Bruker D2 Phaser X-ray diffractometer, which has a Cu Kα source (λ = 1.5406 Å) operating at 40 kV. The XRD spectrum is displayed in Fig. 3.

Due to the intensity difference between the <400> and <800> peaks, compared to the other peaks, we can conclude that the respective layers are predominantly <100>-oriented LuAG, but clearly containing additional crystal domains. The surface topology of the waveguide was studied using a KLA Tencor P-16 + Stylus Profiler and a ZeMetrics ZeScope Optical Profiling System. Measurements indicate a slightly convex profile, with thickness of 8.0 ± 0.1 µm at the central part of the substrate, decreasing at the edges to 7.0 ± 0.1 µm. The rms roughness of the as-grown surface was evaluated to be Sa = 1.67 nm.

Refractive index measurements, for a 0.7 µm-thick Yb(7%):LuAG film grown under the same conditions as the multilayer sample were made with a Metricon (2010) m-line prism coupling system at a wavelength of 632.8 nm. A refractive index of 1.8455 ± 0.0005 was obtained for the Yb(7%):LuAG layer and 1.8296 ± 0.0005 for the YAG substrate. The measured refractive index for YAG was almost identical to that previously reported by Kuwano et al. [26]. The refractive index of undoped LuAG is also given in the same paper as 1.8389 at 632.8 nm. Applying the Sellmeier equations to translate the refractive index values to those for 1 µm, we obtained 1.8148 for YAG, 1.8244 for LuAG and 1.831 for Yb(7%):LuAG. Using these values the modal properties of the waveguide structure were calculated. A waveguide with the parameters detailed should support five guided modes at a wavelength of 1 μm as shown in Fig. 4, as needed to be pumped by a non-diffraction-limited pump source.

With an index contrast of 6.6 × 10−3 between the core and adjacent layers, and for a full waveguide width of only 8 µm, for the ideal waveguide we would expect the fundamental mode to dominate under lasing conditions, due to saturation of the gain available to the other modes [2].

3 Spectroscopy and losses

A fluorescence spectrum from the Yb3+-ions in the core of the multilayer sample was measured using an optical spectrum analyzer (ANDO AQ6317B), set to a resolution of 0.2 nm. Excitation of the ions was achieved as detailed in the previous section to record the image in Fig. 2c. However, in this case the fluorescence signal was captured perpendicular to the waveguide through the top surface using a 0.275-NA optical fibre, 62.5-µm core-diameter, positioned in close proximity to the input facet. This collection geometry deliberately produced a minimal travel distance for the fluorescence through the doped material, effectively reducing the spectrally dependent re-absorption loss from the Yb ions. A fluorescence lifetime for the Yb3+ ions was measured using a similar setup, simply modulating the 974-nm diode laser and replacing the optical fibre with a lens to capture the emission through the surface and focus it onto an InGaAs Amplified Detector (Thorlabs PDA10CS-EC) set to 40 dB gain, which has a 320-kHz bandwidth. A single exponential fluorescence decay was measured as displayed in Fig. 5a with a fitted lifetime of 953 ± 5 µs, which is in good agreement with the results previously measured in ytterbium-doped bulk garnet crystals, namely 965 μs and 985 μs for the 10% and 15% doped Yb:LuAG, respectively [21].

The stimulated emission cross-section spectrum, shown in Fig. 5b, was calculated from the fluorescence spectrum using the Füchtbauer–Ladenburg equation [27] assuming a constant refractive index of 1.831, the measured lifetime, and a unity quantum efficiency; as typically done for ytterbium-doped gain media. To calculate the absorption cross section, shown in Fig. 5b, the reciprocity method was employed using the Stark levels reported in [28]. Whilst the overall spectrum shape is comparable to that reported for the bulk crystal [21], the amplitude of the zero phonon line (ZPL) peak at 970 nm is nearly double. The absorption maximum on the blue side of the ZPL was found to be at 940 nm with a cross-section of 6.1 × 10−21 cm2. This value is close to that previously reported in [21] (7.2 × 10−21 cm2), which was determined from absorption measurement. Moreover, we observed a significant difference in peak stimulated emission cross-section in the band around 1030 nm. In our case, the maximum emission cross-section is 1.6 × 10−20 cm2 with a bandwidth (FWHM) of 11 nm, whereas it is significantly higher in a bulk single crystal, equal to 2.6 × 10−20 cm2 with a bandwidth of 6.3 nm [21]. It is unclear at this stage what is the main cause for the variation in the crystal field environment of the Yb3+ ions in our PLD-grown crystalline film. It may come from an imperfect stoichiometry that is known to occur with aluminium loss during deposition, which is evidenced by the slightly smaller XRD <400> peak value at 29.8° offset from the accepted LuAG peak at 30.0° [29]; inherent strain due to the hetero-epitaxial structure; or simply the slightly polycrystalline nature of the film, as discussed previously. Nevertheless, the broader emission spectrum around 1030 nm offers a distinct advantage for this material for amplifying sub-ps laser pulses compared with Yb:YAG.

To determine the propagation loss for the waveguide sample, the beam from a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser was coupled into the double-clad structure and the transmitted power measured at the output. This wavelength does not fall within the Yb:LuAG absorption band; therefore, absorption is assumed to be negligible. An overall loss of 1.93 dB after the 9.5 mm-long waveguide was observed. Assuming Fresnel reflections from the facets of the waveguide total 0.77 dB, and that there is zero coupling loss, the worst case maximum propagation loss per pass is 1.16 dB, i.e. 1.22 dB·cm−1. This is a typical value for propagation losses in PLD-grown single-layer waveguides and represents a good starting point for the double-clad structure detailed here.

4 Laser experiments

Laser experiments were carried out using a quasi-monolithic plane–plane cavity, shown in Fig. 6. A pump input mirror (M1) was positioned in close proximity to one facet of the waveguide, and similarly for an output coupling mirror (M2), at the opposite uncoated facet, or, simply relying on the ~ 8.5% Fresnel reflection to provide feedback. No index matching fluid was used in the gap between the waveguide facet and mirror surface. The waveguide was mounted on a five-axis translation stage (three linear dimensions plus roll and yaw with respect to the optic axis of the cavity). A conduction-cooled 40 W diode-laser bar operating at 940 nm, with fast- and slow-axis collimation, was used as the pump source. The fast axis of the diode-laser output was expanded using a 5.0 × cylindrical telescope (C1 and C2), then focused by an acylindrical lens (AC1) to a second moments, D4σ, beam height of 6.0 μm at the waveguide facet. In the orthogonal axis, the unguided plane, the beam was focused (C3) to a D4σ width of 1.5 mm around the middle of the sample. The laser output was collected using an aspheric lens (A1) and reflected by a dichroic mirror (DM1) onto a power meter.

Waveguide laser experimental setup: C1–C2—fast-axis cylindrical-lens 5 × telescope; C3—slow-axis focusing cylindrical lens, f = 50 mm; AC1—fast-axis focusing acylindrical lens, f = 10 mm; M1—input mirror (AR@910-990 nm, HR@1020–1100 nm); WG—planar waveguide; M2—output coupler (PR@1030 nm); A1—aspheric lens, f = 15 mm; DM1—dichroic mirror (AR@940 nm, HR@1030 nm); PM—power meter

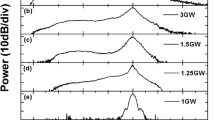

Lasing was characterised with the second facet’s Fresnel reflection providing the cavity feedback, or partially reflecting mirrors (M2) with reflectance values of 30 or 50% were used, as illustrated in Fig. 7a. The best laser performance was achieved in the case of Fresnel reflection with the maximum output power reaching 3.3 W with an emission wavelength of 1030.7 nm. The calculated slope efficiency with respect to absorbed power was found to be 20.0 ± 0.2%. With a 30% R output coupler the maximum output power of the laser decreased slightly to 3.1 W, as the slope efficiency reduced to 17.1 ± 0.2%. A further increase in the output coupler reflectivity up to 50% resulted in an even larger reduction in maximum output power to 2.2 W with a 12.5 ± 0.2% slope efficiency. The laser spectral bandwidth at half maximum of 0.23 nm was measured using a 62.5-µm core-diameter connected to the optical spectrum analyzer with 0.1 nm resolution and 10 pm step interval.

Using a modified Caird analysis accounting for large round-trip loss [30], a cavity loss per pass was determined to be 1.78 dB, as shown in Fig. 7b. This value exceeds the waveguide propagation loss determined via the passive transmission loss measurement; the deficit is assumed to be due to additional coupling losses associated with the finite distance between M1/M2 and the WG, and practical limitations for achieving perfectly polished facets. Laser beam quality was characterised with an Ophir Nanoscan (model NS2-GE/9/5-STD) using cylindrical lenses to collimate the output beam in the orthogonal axes. An example beam profile is shown in Fig. 7b as an insert. A second-moments beam-quality measurement established the waveguide output to have an M2 of 3.3 in the guided axis, at full power. However, in the non-guided direction significant intensity variation across the beam gave a best M2 value of 86 in this axis. We believe that the rather poor beam quality is primarily associated with scattering by particulates/defects in the film and, as later discovered, imperfect facet polishing. With additional fabrication process optimization, employing a bi-directional target ablation technique [24] and improved facet preparation, a reduction in the waveguide propagation losses will be achieved, enabling more efficient laser performance and better laser beam quality.

5 Conclusion

A novel multi-layered LuAG/Yb:LuAG/LuAG crystalline waveguide was fabricated by hetero-epitaxial PLD on a YAG substrate. Textured crystal structure was obtained with a predominance of <100> LuAG orientation, as determined by X-ray diffraction measurements. The modal structure of the fabricated double-clad waveguide was modelled and theoretically shown to support five guided modes, which backed-up experimental observations. Calculated cross section spectra are in reasonable agreement with that previously reported for bulk crystals, along with an excited-state lifetime of 953 µs. In the spectral region of maximum gain, around 1030 nm, broadening of the emission peak was observed for our waveguide material, which may be favourable for ultrashort-pulse amplification. For the first time to our knowledge, laser oscillation with a Yb:LuAG double-clad planar waveguide is demonstrated. End-pumped with a diode-laser bar an output power of 3.3 W is achieved at 1030.7 nm, with a maximum slope efficiency of 20 ± 0.2%, with respect to the absorbed pump power. A propagation loss of 1.2 dB cm−1 for the multi-layered waveguide was determined by an end-fire transmission measurement. While currently not compatible with efficient laser performance these are exemplary values for PLD-grown multi-layer waveguides. Recent work in our group [24] has shown an almost tenfold reduction in linear propagation losses for PLD-grown YGG films. With improved and optimised processes, we see the potential for comparable results in LuAG films.

References

C. Grivas, Optically pumped planar waveguide lasers: part II: gain media, laser systems, and applications. Prog. Quantum Electron. 45–46, 3–160 (2016)

J.I. Mackenzie, Dielectric solid-state planar waveguide lasers: a review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 13(3), 626–637 (2007)

D. Pelenc, B. Chambaz, I. Chartier, B. Ferrand, C. Wyon, D.P. Shepherd, D.C. Hanna, A.C. Large, A.C. Tropper, High slope efficiency and low threshold in a diode-pumped epitaxially grown Yb:YAG waveguide laser. Opt. Comms. 115(5–6), 491–497 (1995)

C.L. Bonner, T. Bhutta, D.P. Shepherd, A.C. Tropper, Double-clad structure and proximity coupling for diode-bar-pumped planar waveguide lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 36(2), 236–242 (2000)

U. Griebner, R. Grunwald, H. Schönnagel, Thermally bonded Yb:YAG planar waveguide laser. Opt. Comms. 164(4–6), 185–190 (1999)

D. Filgas, T. Clatterbuck, M. Cashen, A. Daniele, S. Hughes, D. Mordaunt, Recent results for the raytheon RELI program. Proc. SPIE 8381, 83810W (2012)

S.J. Beecher, J.A. Grant-Jacob, P. Hua, J.J. Prentice, R.W. Eason, D.P. Shepherd, J.I. Mackenzie, Ytterbium-doped-garnet crystal waveguide lasers grown by pulsed laser deposition. Opt. Mater. Express 7, 1628–1633 (2017)

I.J. Thomson, F.J.F. Monjardin, H.J. Baker, D.R. Hall, Efficient operation of a 400 W diode side-pumped Yb:YAG planar waveguide laser. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 47(10), 1336–1345 (2011)

K. Sueda, H. Takahashi, S. Kawato, T. Kobayashi, High-efficiency laser-diodes-pumped microthickness Yb:Y3Al5O12 slab laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 151110 (2005)

C.G. Leburn, C.Y. Ramírez-Corral, I.J. Thomson, D.R. Hall, H.J. Baker, D.T. Reid, Femtosecond pulses at 50-W average power from an Yb:YAG planar waveguide amplifier seeded by an Yb:KYW oscillator. Opt. Express 20, 17367–17373 (2012)

Y.E. Romanyuk, C.N. Borca, M. Pollnau, S. Rivier, V. Petrov, U. Griebner, Yb-doped KY(WO4)2 planar waveguide laser. Opt. Lett. 31, 53–55 (2006)

F.M. Bain, A.A. Lagatsky, S.V. Kurilchick, V.E. Kisel, S.A. Guretsky, A.M. Luginets, N.A. Kalanda, I.M. Kolesova, N.V. Kuleshov, W. Sibbett, C.T.A. Brown, Continuous-wave and Q-switched operation of a compact, diode-pumped Yb3+:KY(WO4)2 planar waveguide laser. Opt. Express 17, 1666–1670 (2009)

J.W. Kim, S.Y. Choi, D.-I. Yeom, S. Aravazhi, M. Pollnau, U. Griebner, V. Petrov, F. Rotermund, Yb:KYW planar waveguide laser Q-switched by evanescent-field interaction with carbon nanotubes. Opt. Lett. 38, 5090–5093 (2013)

W. Bolaños, F. Starecki, A. Braud, J.-L. Doualan, R. Moncorgé, P. Camy, 2.8 W end-pumped Yb3 + :LiYF4 waveguide laser. Opt. Lett. 38, 5377–5380 (2013)

D.L. Veasey, D.S. Funk, P.M. Peters, N.A. Sanford, G.E. Obarski, N. Fontaine, M. Young, A.P. Peskin, W.-C. Liu, S.N. Houde-Walter, J.S. Hayden, Yb/Er-codoped and Yb-doped waveguide lasers in phosphate glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 263(264), 369–381 (2000)

S.J. Beecher, J.A. Grant-Jacob, T.L. Parsonage, P. Hua, A. Choudhary, J.I. Mackenzie, D.P. Shepherd, R.W. Eason, Growth and initial experiments demonstrating watt level output from Yb:YAG planar waveguides grown by pulsed laser deposition. Advanced Solid State Lasers, OSA Technical Digest (online) (Optical Society of America, 2015), paper ATu1A.9

J.A. Grant-Jacob, S.J. Beecher, T.L. Parsonage, P. Hua, J.I. Mackenzie, D.P. Shepherd, R.W. Eason, An 11.5 W Yb:YAG planar waveguide laser fabricated via pulsed laser deposition. Opt. Mater. Express 6, 91–96 (2016)

S. Kurilchik, J. Grant-Jacob, J. Prentice, P. Hua, R. Eason, and J. Mackenzie, Pulsed-laser-deposited Yb:YAG planar-waveguide amplifier. Presented at 8th EPS-QEOD Europhoton Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 2–7 Sept. 2018

T. Bhutta, J.I. Mackenzie, D.P. Shepherd, R.J. Beach, Spatial dopant profiles for transverse-mode selection in multi-mode waveguides. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 19, 1539–1543 (2002)

J.I. Mackenzie, J.W. Szela, S.J. Beecher, T.L. Parsonage, R.W. Eason, D.P. Shepherd, Crystal planar waveguides, a power scaling architecture for low-gain transitions. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 21(1), 380–389 (2015)

K. Beil, S.T. Fredrich-Thornton, F. Tellkamp, R. Peters, C. Kränkel, K. Petermann, G. Huber, Thermal and laser properties of Yb:LuAG for kW thin disk lasers. Opt. Express 18, 20712–20722 (2010)

B. Wang, J. Haihe, X. Jia, Q. Zhang, D. Sun, S. Yin, Thermal conductivity of doped YAG and GGG laser crystal. Front. Optoelectron. China 1, 138–141 (2008)

C. Ma, J. Zhu, K. Liu, F. Tang, J. Long, Z. Wen, R. Ma, X. Yuan, W. Guo, J. Li, Y. Cao, Longitudinally diode-pumped planar waveguide YAG/Yb:LuAG/YAG ceramic laser at 1030.7 nm. Opt. Lett. 41, 3317–3319 (2016)

J.J. Prentice, J.A. Grant-Jacob, S.V. Kurilchik, J.I. Mackenzie, R.W. Eason, Particulate reduction in PLD-grown crystalline films via bi-directional target irradiation. Appl. Phys. A 125, 152 (2019)

T.C. May-Smith, A.C. Muir, M.S.B. Darby, R.W. Eason, Design and performance of a ZnSe tetra-prism for homogeneous substrate heating using a CO2 laser for pulsed laser deposition experiments. Appl. Opt. 47, 1767 (2008)

Y. Kuwano, K. Suda, N. Ishizawa, T. Yamada, Crystal growth and properties of (Lu, Y)3Al5O12. J. Cryst. Growth 260(1–2), 159–165 (2004)

P.F. Moulton, Spectroscopic and laser characteristics of Ti:Al2O3. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 3(1), 125–132 (1986)

A. Brenier, Y. Guyot, H. Canibano, G. Boulon, A. Ródenas, D. Jaque, A. Eganyan, A.G. Petrosyan, Growth, spectroscopic, and laser properties of Yb3+-doped Lu3Al5O12 garnet crystal. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 23, 676–683 (2006)

“Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD)”. http://icsd.cds.rsc.org

J. Morris, N.K. Stevenson, H.T. Bookey, A.K. Kar, C.T.A. Brown, J.-M. Hopkins, M.D. Dawson, A.A. Lagatsky, 1.9 µm waveguide laser fabricated by ultrafast laser inscription in Tm:Lu2O3 ceramic. Opt. Express 25, 14910–14917 (2017)

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) Grants no. EP/L021390/1 and EP/N018281/1. The authors thank Ping Hua for her sample processing expertise. The experimental data included in this paper can be found at https://doi.org/10.5258/soton/d0782.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kurilchik, S.V., Prentice, J.J., Eason, R.W. et al. Characterisation and laser performance of a Yb:LuAG double-clad planar waveguide grown by pulsed laser deposition. Appl. Phys. B 125, 201 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00340-019-7314-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00340-019-7314-9