Abstract

An analytical model is presented, which allows estimating the expected dose rates resulting from X-ray emission from ultra-short-pulse laser-produced plasma under industrial conditions. The model is based on the calculation of the Bremsstrahlung spectrum in the X-ray region between about 5 keV and 50 keV, which is created by the hot electrons in the plasma. The model was calibrated with both spectral and dose rate measurements. The scaling of the hot-electron temperature and the fraction of hot electrons in the plasma served as calibration values. The agreement between experiments and model for the investigated irradiances in range from 1012 to 1015 W/cm2 is excellent. The expected \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) and \(\dot{H}\)(10) dose rates at a distance of 20 cm from the process in air were calculated for upcoming lasers with 1 kW of average power. Although the dose rates close to the plasma significantly exceed the allowed dose of 50 mSv per year for an irradiance exceeding about 2·1015 W/cm2, the calculations show that shielding with a 2-mm sheet of iron already at a distance of 20 cm attenuates the radiation to a safe value below 0.4 µSv/h.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Materials processing with so-called ultrafast lasers with pulse durations below about 10 ps has been proven to allow very precise processing of a wide range of materials with mechanical and thermal accuracies in the micrometer range [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. In the last years, materials processing with ultrafast lasers has gained attention for industrial applications due to the increase of the average power up to the 100-W region, allowing reasonable productivity. Today, the next generation of ultrafast laser systems, with several kilowatt of average power, has already been demonstrated in the laboratory [8, 9]. Although the optimum irradiance for efficient processing with high quality is in the range of 1011–1012 W/cm2 as shown in [10], for example, such lasers allow one to achieve irradiances of up to about 1015 W/cm2 on the surface of the workpiece using appropriate focusing. Such high laser irradiances lead to hot-electron temperatures in the plasma of up to several keV [11] that result in Bremsstrahlung, recombination and line emission in the keV X-ray region. X-ray emission from laser-produced plasma is well known and has been investigated since the early 1980ies [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. X-rays emitted from laser-induced plasma were used, in particular, in indirect driven fusion and X-ray laser research, later also for X-ray lithography and X-ray spectroscopy. The conversion efficiency was investigated and optimized in particular for laser irradiances in the range of 1014 W/cm2 up to more than 1020 W/cm2, with the plasmas produced in a vacuum chamber, e.g. [18,19,20,21,22,23].

On the other hand, only little work was published for the X-ray emission from plasma under industrial processing conditions, i.e., in ambient air at atmospheric pressure, at rather moderate irradiances of 1010–1014 W/cm2, and for average laser powers up to a few 100 W. One of the reasons is that air is not transparent for radiation with photon energies in the range of a few eV up to about 5 keV. Although the fraction of radiation above 5 keV from these plasmas is low, the X-ray emission might become an issue with increasing average power of the ultrafast lasers, because the dose rate increases proportionally with the average power. Of special interest are the dose rates \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) and \(\dot{H}\)(10) which describe the absorbed X-ray energy per mass and time in a depth of the body of 0.07 mm and 10 mm, respectively. The former value mainly considers X-ray photon energies around 5 keV, the latter photon energies at about 30 keV. Recently, Legall et. al. published extensive measurements of the X-ray emission from laser-produced plasma under industrial processing conditions [11]. The results clearly showed that at irradiances well above 1014 W/cm2 X-ray photons with energies up to about 25 keV could be observed. These results were confirmed in [24]. Furthermore, \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) dose rates exceeding 105 µSv/h were measured at a distance of 20 cm from the plasma. However, the scaling of the X-ray dose as a function of the processing parameters under industrial processing conditions is not yet established.

The present paper presents an analytical approximation for the Bremsstrahlung emission, which was experimentally calibrated. The model allows one to estimate the dose rates created during processing with upcoming kilowatt-level lasers, and therefore to determine the required shielding of the laser processing cell for safe operation.

2 Analytical description of the Bremsstrahlung emission

2.1 Thermal Bremsstrahlung emission from laser-produced plasma

The irradiation of material with high-intensity, ultra-short laser pulses results in a plasma with very hot electron temperatures. The interaction of the free, fast electrons with ions results in Bremsstrahlung, recombination and line emission. The resulting spectrum is the sum of the three contributions. These radiation processes are described in detail in [25] and [26], which serve as basis for this work. The line emission strongly depends on the material which is processed. Following the argumentation in [26] for the emission from laser-produced plasma as considered here, the following can be summarized: for materials with a low atomic number such as Plastic ("low-Z", Z ≤ 8), the emission is essentially Bremsstrahlung, and the line emission can be neglected. For high-Z materials (Z ≥ 30) such as tungsten or gold, the large number of lines results in a quasi-continuum emission similar to Bremsstrahlung. In medium-Z materials such as aluminum or iron (8 < Z < 30), strong line emission might occur, mainly from the so-called resonance lines to the principle ground states, and in particular the K-alpha line. In the current work, only the part of the spectrum in the high-energy range between about 3 keV and about 15 keV is of interest. Although the K-alpha lines have a very high spectral brightness, the contribution to the total emission is only a few percent [26]. Therefore, only Bremsstrahlung is considered in the following.

In [25, 26] approximation formulae are derived for dPB/dω, the emitted Bremsstrahlung power PB per unit frequency ω. The derivations are based on the calculation of the number of Coulomb collisions of ions and free electrons, which have a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution of their kinetic energy. While the electrons are heated, the ions usually remain cold during the ultrashort-pulse interaction [12]. However, at very high irradiances, two electron temperatures develop during the laser–plasma interaction, the so-called cold-electron temperature of a few 100 eV at high plasma densities in the range of solid-state density and the so-called hot-electron temperature exceeding 1 keV as described in detail in [26]. The hot-electron temperature is even increased when resonance absorption occurs [13]. Due to their much higher temperature, mainly the hot electrons contribute to the spectrum of the Bremsstrahlung > 5 keV. In [26] analytical expressions for dPB/dω are derived in particular for dense, laser-produced plasma for Bremsstrahlung and recombination emission. The contribution of the recombination emission is similar to the Bremsstrahlung emission but shows additional edges in the spectrum at the energies of the different basic quantum states [26]. As no edges were seen in the measured high-energy part of the spectra discussed here, only the approximation for Bremsstrahlung is used in the following for estimating the scaling of the x-ray emission and the corresponding dose rates. The emitted power per unit frequency is therefore assumed to be [26]

where kB and are the Boltzmann and the Planck constants, respectively, c the speed of light, and me and e the electron-mass and charge, respectively. VP is the emitting plasma volume. The plasma properties, which are relevant for the X-ray emission, are the electron temperature, kBTe (usually expressed as energy in electron volts), the degree of ionization, Zi, and the number density of the hot electrons, nh. In contrast to the original formula given in [26], the emitting plasma volume is explicitly included in (1). The plasma is considered as quasi-neutral, i.e., the electron number density equals the degree of ionization times the ion number density, ne = Zi.ni. The exponential function in Eq. (1) describes the spectrum that is solely defined by the hot-electron temperature.

As seen in [11, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30] the plasma properties kBTh, Zi, and nh are complicated functions of space and time. However, for this work it is assumed that the predominant part of the Bremsstrahlung emission in the part of the spectrum of interest is produced by the hot electrons, during the laser pulse, and at a constant hot-electron temperature in a local thermal equilibrium. This leads to the approximations, which are discussed in the following.

2.2 Emitting plasma volume

The volume of the emitting plasma, VP, is taken as the ablated area times the ablation depth plus the contribution due to expansion. The plasma expands with the ion’s speed of sound. In the beginning of the process, which is of interest here, i.e., during the duration tP of the laser pulse, the expansion is purely perpendicular to the surface, yielding

where the ablation radius and the ablation depth for a Gaussian beam are given by

respectively, where ηabs is the absorption coefficient, EP the laser pulse energy, rF the radius of the beam on the surface, \(\ell_o\) the optical penetration depth, and hV the volume-specific enthalpy for evaporation of the considered material. It is noted that \(\ell_o \cdot h_v/\eta _{\rm abs}\) = Φth is the ablation threshold. In the present model, Eq. (3) does not consider energy transport by fast electrons. The ion’s speed of sound is given by

where mi is the mass of the ions.

2.3 Hot-electron number density

As already mentioned, the plasma is assumed to be quasi-neutral. Furthermore, it is assumed that only the fraction qh of the free electrons is hot, yielding the hot-electron number density

The ion number density is assumed to be the solid-state number density, decreasing with increasing plasma volume. With Eq. (2) the ion density becomes

where ρ is the density of the material.

The fraction qh is used in the following as a free parameter to fit the analytically derived expressions to the experimentally determined dose rates.

2.4 Degree of ionization

For calculating the degree of ionization in the plasma, the ionization level i as a function of the corresponding energy required for ionization, Ei, was approximated with a simple empirical fit

where ZE is the atomic number of the element and Ei,max the highest ionization energy. If Zi exceeds ZE, then Zi is set to ZE. A comparison of the fit with the ionization energies is given in the appendix for aluminum, iron, and tungsten. This simple fit can be used to obtain an estimate for the average degree of ionization Zi in the plasma by simply replacing Ei by the average kinetic energy of the hot electrons with three degrees of freedom, yielding

2.5 Hot electron temperature

The knowledge of both the hot-electron temperature and the scaling of the hot-electron temperature with the laser irradiance is crucial for the calculation of the scaling of the dose rate. In the literature, scaling laws are found for the hot-electron temperature in keV, determined with a variety of measurement methods, typically in the form of

where cT is a constant with the unit keV/(µm2 W/cm2), λL is the laser wavelength in micrometers, and

the irradiance in the center of the incident Gaussian beam averaged over the pulse duration in W/cm2. The exponent s is in the range of 0.3–0.5 and varies for different experimental conditions as found in [11, 24, 27,28,29,30], for example. It is seen that the hot-electron temperature only depends on the laser wavelength and the irradiance. In particular, it is independent of the material and of the pulse duration. However, as already mentioned, data was only published for IL > 1014 W/cm2.

2.5.1 Determination of the hot-electron temperature

The emission spectrum given in Eq. (1) was used to fit the measured spectra, in order to determine the temperature of the hot electrons. This spectrum can be expressed in the form

where TA(ω) and TF(ω) are the known frequency-dependent transmissions through air and all filters in front of the detector, respectively. As can be seen from Eq. (1), the constant cE is a function of the average degree of ionization, the hot-electron density, and the temperature and is therefore different for each spectrum, but does not depend on ω. The constant cE was used as a fit value to adapt the level of the calculated spectrum to the measured signal levels. The shape of the spectrum is purely determined by the hot-electron temperature Th and the transmission of the air and the filters in the experimental setup.

Figure 1 shows the emission spectra measured with a silicon-drift detector (PNDetector GmbH, Munich, Germany) for different laser irradiances. The measurements were made through air at atmospheric pressure at a distance of 13.5 cm (left) and 20 cm (right). It is noted that great care was taken to avoid the so-called pile-up effect. The sample material was tungsten. The laser provided pulses with a duration of 0.9 ps (left) and 0.24 ps (right). The laser pulse energy was 0.18 mJ, the repetition rate 100 kHz, and the beam was focused onto the surface of the sample to a focus diameter of 45 µm in both cases. This resulted in irradiances I0 of 2.6.1013 W/cm2 (left) and 9.8.1013 W/cm2 (right). The orange dashed lines represent manual fits to the spectra using Eq. (11). For the two fits shown in Fig. 1, the resulting temperature is 0.48 keV (left) and 0.82 keV (right).

Spectra of the thermal Bremsstrahlung emission from tungsten plasma generated by a laser with a wavelength of 1 µm, with a pulse duration of 0.9 ps, and an irradiance I0 of 2.6.1013 W/cm2 (left) as well as with a pulse duration of 0.24 ps and an irradiance I0 of 9.8.1013 W/cm2 (right). The orange dashed lines represent fits according to Eq. (11) yielding a temperature of 0.45 keV (left) and of 0.82 keV (right)

The position of both the maximum of the emission and the decrease of the emission towards higher photon energies is very sensitive to the temperature, which is used to the fit Eq. (12) to the experimental data. By considering the divergence between fit and measured data when changing the fit parameter Th, the accuracy of the temperature determined by this method was estimated to be better than ± 15%.

2.5.2 Scaling of the hot-electron temperature

Spectra were recorded for different pulse durations, pulse energies, focal diameters of the incident laser beam and different materials. The temperatures resulting from these measurements are shown as blue squares in Fig. 2. The error bars correspond to ± 15% as stated above. The gray (dashed) line represents the temperature scaling as given in [11] and Eq. (10) with cT = 3.65.10–5 and s = 1/3. The blue (dash-dotted) line represents a least-square fit of Eq. (10) to the data with cT = 2.1.10–6 and s = 0.41, and the orange (solid) line the scaling given by Eq. (10) with cT = 4.1.10–5 and s = 0.53, which leads to very good agreement of the model with the measured spectra and dose rates as will be shown later.

Hot-electron temperatures as a function of the irradiance multiplied by the laser wavelength in micrometers squared determined from the measured spectra for different setups. The gray (dashed) line represents the temperature scaling as given in [11], the blue (dash-dotted) line represents a least-square fit to the data, and the orange (solid) line the scaling which leads to very good agreement of the model with the measured spectra and dose rates

The large scattering of the data points is typical for measurements of the hot-electron temperature as also seen in [11, 24, 27,28,29,30], for example, and was not further investigated. The temperatures were determined mainly to prove the validity of the assumptions made for s and cT to experimentally verify the model.

3 Dose rates

As described in the introduction, due to radiation safety issues it is of special interest in industrial applications to know the scaling of the dose rate with the laser processing parameters.

3.1 Calculation of the dose rate

The dose rate \(\dot{H}\)(dP) is the energy per mass per time of ionizing radiation absorbed within a specified depth dP. It is a measure for possible harm to human beings. The allowed limits are varying among the countries and are typically below the natural radiation exposure, which can be up to a few hundred mSv per year. A typical limiting value for X-ray exposure is 50 mSv/a, which will be used for reference in the following.

The absorbed mass-specific enthalpy H(ω,z) as a function of the depth z for X-radiation of a certain frequency ω inside a body of density ρM, which has an optical penetration depth of \(\rho\)a(ω) is described by Beer's law

where ΦA (ω) = ηabs Φ0 (ω) and Φ0 (ω) is the absorbed and the incident fluence of the x-ray radiation, respectively, and \(\ell\)a() is the optical penetration depth. The plasma is assumed to emit the X-radiation given in Eq. (1) isotropically in the free half-space. Therefore, ΦA(ω) decreases with the square of the distance from the plasma, dD. Furthermore, it is assumed that the plasma emits during the pulse duration tP, yielding the fluence

for a single laser pulse, where SD(ω) is the relative spectral sensitivity of the detector and TA(ω) and TF(ω) are the spectral transmission through air and all filtering materials between the plasma and the sensor, respectively.

For calculating dose rates, the density ρICRU and the optical penetration depth \(\ell\)a,ICRU(ω) of the so-called ICRU-sphere have to be used. The ICRU-sphere is normalized human tissue with a density of 1 g·cm−3, consisting of 76.2% of oxygen, 11.1% of carbon, 10.1% of hydrogen, and 2.6% of nitrogen. With these assumptions, the dose rate for a given penetration depth dP in a body, applying a certain repetition rate fL of the laser, can be calculated by integrating Eq. (14) over all frequencies, resulting in

According to this result, the dose rate is determined in particular by dPB/dω, which according to Eqs. (1) and (10) depends on the incident laser irradiance I0, and scales with the product of pulse duration and pulse repetition rate. This means that the dose rate is directly proportional to the absorbed average laser power.

3.2 Comparison of the calculated dose rates with experiments

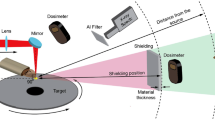

3.2.1 Experimental setup

Dose rates were measured for processing of mild steel. (In the Appendix, model calculations are compared with experimental results obtained with aluminum and tungsten from [11]).

The laser used for the measurement of the dose rate at GFH GmbH had a wavelength of 1.03 µm, a pulse duration of 921 fs, a constant repetition rate of 300 kHz, and a maximum pulse energy of 346 µJ, yielding a maximum average power of 104 W. The beam was tightly focused to a diameter of 11 µm resulting in a maximum irradiance I0 of 6.8.1014 W/cm2. The \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) dose rate was measured at a distance of 20 cm with two OD-02 dosimeters (STEP GmbH, Pockau, Germany), which were made light-tight with a 8 µm thick Be filter. It is noted that the OD-02 can be used with an additional filter cap to measure the much more dangerous \(\dot{H}\)(10) dose rates. However, according to the manufacturer this arrangement cannot be used for photon energies below about 15 keV. Therefore, only the \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) is discussed in the following.

For the following calculations, the data for the X-ray absorption and transmission for the involved materials was taken from [31], and for each approximated by a simple power fit over the range from 1 to 30 keV. The values, which were used, are given in the appendix. The relative sensitivity of the OD-02 sensor is changing only by about ± 10% between 5 and 30 keV and was therefore assumed as constant.

3.2.2 Measured \(\dot{H}\) (0.07) dose rate

Great care has to be taken to record the maximum dose rates. With every pulse, some material is evaporated and a small dimple created. Shielding of the emitted X-rays due to kerf walls or borehole walls around the processed region can significantly influence the measured dose rate [32]. For the present experiments, the laser spot was scanned over a small area of 20 mm × 20 mm on the surface of the steel sample with the direction of movement of the beam towards the detector. The line overlap and the pulse overlap were kept constant at about 75%. This arrangement minimized shielding due to kerf walls and reduced shielding due to remaining particles. Furthermore, the relative distance between the interaction zone and the detectors was constant within better than ± 0.2%. However, as seen in the temperature measurements in Fig. 2, the comparison of different measurements under almost identical conditions still shows a large scattering of the resulting dose rates, yielding uncertainties in the range of ± 90%.

Figure 3 shows the measured dose rates (blue dots) as a function of the irradiance, with vertical error bars of ± 90%. The solid line gives the calculated dose rates using Eq. (14) as explained in the next section.

\(\dot{H}\)(0.07) dose rates, measured (dots) and calculated with Eq. (14) (line) at 20 cm from the interaction zone as a function of the irradiance I0. For the measurements, the irradiance was varied by changing the pulse energy, all other laser parameters (see text) were kept constant

The measured dose rates increase from about 1 µSv/h for laser irradiances of 1013 W/cm2 to more than 106 µSv/h at about 1015 W/cm2. It is noted that the measured dose rates presented here agree very well with the values published in [11] (see also the Appendix).

3.2.3 Expected dose rates

The expected dose rate was calculated with Eq. (14) using the temperature scaling of Eq. (10) with cT = 4.1.10–5, s = 0.53 (cf. Fig. 2), and a laser wavelength of 1 µm. This temperature scaling was chosen because it yields the best fit to the data regarding the scaling of the dose rate with the irradiance. Applying Eq. (8) for iron this temperature scaling yields the average ionization as a function of the irradiance I0 shown in Fig. 4. The average degree of ionization increases from about 10 at an incident irradiance I0 of 3.1011 W/cm2 up to full ionization of 26 at about 7.1014 W/cm2. Above this irradiance, no additional electrons are created with further increasing irradiance.

The fraction of hot electrons was set to qh = 5.5.10–4 to fit the dose rate calculated with Eq. (14) to the measured \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) dose rates shown as blue line in Fig. 3. It is seen that the agreement of the model with the experimental values is excellent over the two orders of magnitude of irradiance I0 considered here.

3.2.4 Dose conversion efficiency

For the measurements of the dose rate presented above, the incident irradiance I0 was increased by increasing the pulse energy Ep, and with it the average power of the laser that was operated at a constant repetition rate. Normalizing the dose rate with the average laser power PL = Ep·fL yields a “H(0.07)-dose conversion efficiency at a distance of 20 cm from the target through air”, i.e. µSv per µJ of pulse energy at a distance of 20 cm, shown as a function of the irradiance in Fig. 5.

This dose conversion efficiency increases more than three orders of magnitude when I0 is increased from 1013 W/cm2 to 1014 W/cm2 and stays almost constant above I0 = 2.1014 W/cm2. The strong increase between I0 = 1013 W/cm2 and I0 = 1014 W/cm2 is consistent with the scaling of the hot-electron temperature that was used for the model, which is steeper than the scaling given in the literature for irradiances above 1014 W/cm2.

3.3 Scaling of the dose rate

3.3.1 Scaling of the dose rate with irradiance at constant average power for kW-class lasers

Figure 6 shows the dependence of the \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) dose rate at a distance of 20 cm, as calculated with Eq. (14) on the irradiance I0 when the average laser power is kept constant. Hence, the increase of the irradiance I0 is achieved by decreasing the focus diameter and keeping all the other parameters constant. It is noted that in this case also the emitting plasma volume is decreased due to the decreasing spot size, as can be seen in Eq. (2). The smallest focus diameter assumed was 10 µm. The blue line in Fig. 6 (left) corresponds to the values in Fig. 3 but at the constant average power of 104 W. It is seen that with 104 W of average power the dose rate at a distance of 20 cm from the interaction zone is already 100 µSv/h at an irradiance I0 of 1013 W/cm2 (blue arrow).

(Left) Expected \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) dose rate at a distance of 20 cm for the constant average laser power of 104 W (blue line) and 1 kW (red line) as a function of the irradiance I0. (Right) Dose rate as a function of the average laser power for an irradiance of 1013 W/cm2 (blue line) and 1014 W/cm2 (red line)

Furthermore, Fig. 6 (left) also shows the expected \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) dose rates for a laser with a pulse duration of 1 ps and constant average power of 1 kW, which is commercially available in very near future. The red line was calculated with a pulse energy of 2 mJ and a repetition rate of 500 kHz. With 2 mJ of pulse energy, an irradiance I0 of more than 6.1015 W/cm2 is achieved with a focus diameter of 10 µm. At an irradiance of I0 of 1013 W/cm2 and at 20 cm from the interaction zone the use of 1 kW of average laser power leads to a dose rate of about 1 mSv/h. Furthermore, it is seen that the dose rate exceeds 50 mSv/h when the beam is focused to I0 exceeding about I0 = 2.1013 W/cm2 (red arrow). It is noted, that the dose rates are identical for each combination of pulse energy and repetition rate, which yields the same irradiance. This means, that at a given irradiance and pule duration the dose rate is solely determined by the average laser power.

This dependence of the dose rate on the average laser power is shown in Fig. 6 (right) for a pulse duration of 1 ps and a focus diameter of 100 µm, for 0.4 mJ (blue line) and 4 mJ (red line) pulse energy yielding irradiances of 1013 W/cm2 and 1014 W/cm2, respectively. For these curves, the average power was increased by increasing the repetition rate from 1 kHz to 50 MHz.

3.3.2 Influence of the pulse duration at constant average power

In addition, the model allows calculating the expected dose rates at a distance of 20 cm as a function of the pulse duration. This is shown in Fig. 7 for the constant average power of 1 kW. Figure 7 (left) shows the expected dose rates for two different pulse energies and repetition rates for a focus diameter of 40 µm. Figure 7 (right) shows the expected dose rates for three different focus diameters at the constant repetition rate of 5000 kHz and a pulse energy of 0.2 mJ.

It is seen that the dose rates show a maximum which moves to longer pulse durations with increasing pulse energy (left) and decreasing focus diameter (right). The maximum occurs, when the irradiance is high enough that the material is fully ionized and Zi = const, i.e. at about 5.1014 W/cm2 for iron (Fig. 4). For Zi = const the assumptions given in Eqs. (2)–(6) and (2) yield a decreasing dose rate from Eq. (14), if the irradiance is increased by decreasing the pulse duration and keeping all other parameters constant.

3.3.3 \(\dot{H}\) (10) dose rates

As already mentioned the OD-02 dosimeters are not suitable for the measurements of the \(\dot{H}\)(10) dose rates when the major part of the spectrum of the emission is below 15 keV, which prevents trustable experiments. However, the model can be used to calculate the expected \(\dot{H}\)(10) dose rates. Figure 8 shows the \(\dot{H}\)(10) dose rates at a distance of 20 cm calculated by Eq. (14) for a pulse duration of 1 ps as a function of the irradiance I0 for the same conditions as in Fig. 6, i.e. a pulse energy of 0.35 mJ, a repetition rate of 300 kHz, and a constant average laser power of 104 W (blue line), and a pulse energy of 0.35 mJ, a repetition rate of 300 kHz, and a constant average laser power of 1 kW (red line).

The resulting dose rates at I0 = 1014 W/cm2 are about five orders of magnitude lower than the \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) dose rates. As the spectrum shifts to higher photon energies with increasing irradiance, i.e. with increasing hot-electron temperature, the \(\dot{H}\)(10) dose rate strongly increases to values comparable to \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) at I0 = 1015 W/cm2. The dose rate of 50 mSv/h is exceeded for irradiances I0 larger than about 4.1014 W/cm2 (red arrow).

4 Radiation protection

The radiation protection against X-rays from ultra-short pulsed laser-produced plasma under industrial conditions is quite simple. Persons are usually much further away from the plasma than 20 cm. In addition, due to laser safety requirements, a housing around the processing zone is needed in any case. Therefore, Fig. 9 shows the calculated \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) and \(\dot{H}\)(10) dose rates assuming a laser with 1 kW of average power at a distance of 100 cm from the plasma (left) and at a distance of 20 cm from the plasma behind a 2 mm thick iron sheet (right). Figure 9 (left) reveals that the radiation is strongly attenuated by the air and the additional distance compared to the dose rates shown in Fig. 6.

Furthermore, it is seen in Fig. 9 (right) that the strong attenuation of iron reduces the dose rates below any critical value for applied irradiances I0 of up to 1015 W/cm2. Since iron with a thickness of 2 mm has a cutoff energy for the photons (10% of transmission) of about 55 keV (data from [31]), the \(\dot{H}\)(0.07) and \(\dot{H}\)(10) dose rates are almost identical. However, one should keep in mind that the dose rate increases linearly with laser power.

5 Summary

An analytical model is presented in this paper, which allows estimating the expected dose rates resulting from X-ray emission from ultra-short-pulse laser-produced plasma under industrial conditions. It allows calculating both the spectral X-ray emission and the resulting dose rate for a given penetration depth in the body as would be suffered at a given distance. The scaling of the hot-electron temperature and the fraction of hot electrons in the plasma serve as calibration values. The model was calibrated with both spectral and dose rate measurements. The agreement between experiments and model is excellent.

The calculations were used to estimate the dose rate created when using upcoming lasers with 1 kW of average power. Although the dose rates close to the plasma might be very high, shielding with a 2-mm sheet of iron attenuates the radiation to a level low enough that, to current knowledge, any endangerment can be excluded.

References

H. Hügel, H. Schittenhelm, K. Jasper, G. Callies, P. Berger, Structuring with excimer lasers—experimental and theoretical investigations on quality and efficiency. J. Laser Appl. 10, 255–265 (1998)

W. Schulz, U. Eppelt, R. Poprawe, Review on laser drilling I: Fundamentals, modeling, and simulation. J. Laser Appl. 25(1), 012006 (2013)

S. Nolte, C. Momma, H. Jacobs, A. Tünnermann, B.N. Chichkov, B. Wellegehausen, H. Welling, Ablation of metals by ultrashort laser pulses. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 14(10), 2716–2722 (1997)

D. Hellrung, A. Gillner, R. Poprawe, Laser beam removal of micro-structures with Nd: YAG lasers. Proc. Lasers Mater Process Laser 97, 267–273 (1997)

E.G. Gamaly, A.V. Rode, Physics of ultra-short laser interaction with matter: From phonon excitation to ultimate transformations. Prog. Quantum Electron 37, 215–323 (2013)

T. Kononenko, V. Konov, S. Garnov, R. Danielius, A. Piskarskas, G. Tamoshauskas, F. Dausinger, Comparative study of the ablation of materials by femtosecond and pico- or nanosecond laser pulses. Quantum Electron 29(8), 724–728 (1999)

R. Weber, C. Freitag, T. Kononenko, M. Hafner, V. Onuseit, P. Berger, T. Graf, Short-pulse laser processing of CFRP. Phys Procedia 39, 137–146 (2012)

Negel J-P, Voss A, Abdou Ahmed M, Bauer D, Sutter D, Killi A, Graf T, 1.1 kW average output power from a thin-disk multipass amplifier for ultrashort laser pulses. Opt. Lett. 38(24), 5442–5445 (2013)

M. Müller, A. Klenke, A. Steinkopff, H. Stark, A. Tünnermann, A. Limpert, 3.5 kW coherently combined ultrafast fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 43(24), 6037–6040 (2018)

B. Neuenschwander, B. Jaeggi, M. Schmid, U. Hunziker, B. Luescher, C. Nocera, Processing of industrially relevant non-metals with laser pulses in the range between 10ps and 50ps. ICALEO 2011, 783 (2011)

H. Legall, C. Schwanke, S. Pentzien, G. Dittmar, J. Bonse, J. Krüger, X-ray emission as a potential hazard during ultrashort pulse laser material processing. Appl. Phys. A 124, 407 (2018)

P.B. Corkum, F. Brunel, N.K. Sherman, T. Srinivasan-Rao, Thermal response of metals to ultrashort-pulse laser excitation. Phys. Rev. Lett 61(25), 2886–2889 (1988)

J.E. Balmer, T.P. Donaldson, Resonance absorption of 1.06-μm laser radiation in laser-generated plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 17 (39), 1084 (1977).

R. Weber, P. F. Cunningham, J. E. Balmer, Temporal and spectral characteristics of soft x radiation from laser-irradiated cylindrical cavities. Appl. Phys. Lett. 53(26), (1988)

R. Weber, J.E. Balmer, Soft X-ray emission from double-pulse laser-produced plasma. J. Appl. Phys. 65, 1880 (1989)

B. Soom, R. Weber, J.E. Balmer, X-ray conversion efficiency in Cu plasma produced by subnanosecond laser pulses. J. Appl. Phys. 68(3), 1392–1394 (1990)

B.A.M. Hansson, Laser-plasma sources for extreme-ultraviolet lithography. Doctoral Thesis, KTH, Stockholm, Sweden (2003) (TRITA FYS 2003-56, ISSN 0280-316X, ISRN KTH/FYS/--03:56--SE, ISBN 91-7283-658-X)

W. Lampart, R. Weber, J.E. Balmer, Comparative X-ray spectroscopy of various-Z elements with wavelength calibration. J. Appl. Phys. 63, 273 (1988)

H. Kim, B. Yaakibi, J. M. Soures, P. C. Cheng, Laser-Produced Plasma as a Source for X-Ray Microscopy, X-Ray Microscopy III, Springer Series in Optical Sciences, vol 67. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 47–53 (1992)

C.A. Back, J. Davis, J. Grun, L.J. Suter, O.L. Landen, W.W. Hsing, M.C. Mille, Multi-keV X-ray conversion efficiency in laser-produced plasmas. Phys. Plasmas 10, 2047 (2003)

Wanli Shang, Jiamin Yang, Wenhai Zhang, Yunsong Dong, Zhichao Li, Bo Deng, Tuo Zhu, Chengwu Huang, Xiayu Zhan, Liang Guo, Yu. Ruizhen, Sanwei Li, Shaoen Jiang, Shenye Liu, Feng Wang, Yongkun Ding, Baohan Zhang, Riccardo Betti, Experimental demonstration of laser to X-ray conversion enhancements with low density gold targets. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 064102 (2016)

L. Miaja-Avila, G.C. O'Neil, J. Uhlig, C.L. Cromer, M.L. Dowell, R. Jimenez, A.S. Hoover, K.L. Silverman, J.N. Ullom, Laser plasma x-ray source for ultrafast time-resolved x-ray absorption spectroscopy. Struct. Dyn. 2, 024301 (2015)

E. Dewald, M. Rosen, S.H. Glenzer, L.J. Suter, F. Girard, J.P. Jadaud, J. Schein, C.G. Constantin, P. Neumayer, O. Landen, X-ray conversion efficiency of high-Z hohlraum wall materials for indirect drive ignition. Phys. Plasmas 15, 072706 (2008)

R. Behrens, B. Pullner, M. Reginatto, X-ray emission from materials processing lasers. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2018, 1–14 (2018)

G. Bekefi, Radiation Processes in Plasmas. Wiley Series in Plasma Physics, 1st edn. (Wiley, 1966)

D. Giulietti, L.A. Gizzi, X-ray emission from laser produced plasma. La Rivista del Nuovo Cimento 21(10), 1 (1998)

H.G. Tan, G.H. McCall, A.H. Williams, Determination of laser intensity and hot electron temperature from fastest ion velocity measurement in laser-produce plasmas. Phys. Fluids 27(1), 296 (1984)

R. Weber, J.E. Balmer, P. Lädrach, Thomson parabola time-of-flight ion spectrometer. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 57(7), 1251 (1986)

S.C. Wilks, W.L. Kruer, M. Tabak, A.B. Langdon, Absorption of ultra-intense laser pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69(9), 1383 (1992)

Y.-Q. Cui, W.-M. Wang, Z.-M. Sheng, Y.-T. Li, J. Zhang, "Laser absorption and hot electron temperature scalings in laser–plasma interactions. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 55, 085008 (2013)

http://henke.lbl.gov/optical_constants/filter2.html. Accessed Jan 2018

H. Legall, C. Schwanke, J. Bonse, J. Krüger, The influence of processing parameters on X-ray emission during ultra-short pulse laser machining. Appl. Phys. A 125, 570 (2019)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the funding of part of this work by the BMBF in the frame of the project ScULP3T. Furthermore, we acknowledge the contribution to parts of the dose rate measurements of G. Dittmar, Aalen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Filter transmissions

Figure 10 shows the absorption coefficient as a function of the photon energy (solid lines) from [31] for the filter materials, which were used in the presented experiments.

For the calculations, a simple power fit (dotted lines) to the data was used. The extent of the fit and the corresponding fit-coefficients are shown in Fig. 10.

1.2 Different materials

To further verify the validity of the model, the calculations were compared with experimental results for aluminum, iron and tungsten from [11].

1.2.1 Ionization level

Figure 11 shows the fit given in Eq. (7) for aluminum (left), iron (middle), and tungsten (right), proving a reasonable approximation for the ionization level i as a function of the respective ionization energy. Other elements might need different fitting parameters

Using the temperature scaling of Th = 4.1.10–5.I00.53 yields the average degrees of ionization Zi for aluminum, iron, and tungsten as shown in Fig. 12.

1.2.2 Spectra of different materials

The influence of the material on the X-ray emission is shown in Fig. 13.

The dashed lines are the spectra calculated with Eq. (11) for tungsten (red), steel (green) and aluminum (yellow) for an irradiance of I0 = 2.6.1014 W/cm2 through air at a distance of 645 mm and a 362-µm thick Al foil as filter in front of the detector. The same temperature scaling as above was used, i.e. Th = 4.1.10–5.I00.53, s = 0.53. The gray background spectra are measurements, which were published in [11]. All calculated spectra were multiplied with the same constant cE, which was set such that the iron spectrum fits the measured relative emission best.

As predicted by the model, the position of the peak of the emission and the temperature belonging to the respective Maxwell–Boltzmann fit are independent of the material. Although the difference between the emissions of the different materials is slightly over-estimated by the model, it very reasonably reproduces the fact that tungsten has the highest emission and aluminum the lowest. The difference between the calculated and the measured spectra might be due to the different contributions of the line emission, which is not considered in the model.

1.2.3 Dose rates

Figure 14 shows the comparison of calculated (dashed lines) dose rates and the measured dose rates published in [11] (gray background) for the three materials. The experimental conditions reported in [11] were used to calculate the dose rate for the three materials. Both the temperature scaling and the fraction of hot electrons were kept identical as above, i.e., Th = 4.1.10–5.I00.53, s = 0.53, and qh = 5.5.10–4.

Overlay of the absolute values of the calculated dose rates (dashed lines) and the dose rates measured in [23] (gray background) for tungsten (red), steel (green) and aluminum (yellow)

While the calculated emission for tungsten is about a factor of three too high, the agreement for iron and for aluminum is excellent.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Weber, R., Giedl-Wagner, R., Förster, D.J. et al. Expected X-ray dose rates resulting from industrial ultrafast laser applications. Appl. Phys. A 125, 635 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-019-2885-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-019-2885-1