Abstract

Early research into coral reproductive biology suggested that spawning synchrony was driven by variations in the amplitude of environmental variables that are correlated with latitude, with synchrony predicted to break down at lower latitudes. More recent research has revealed that synchronous spawning, both within and among species, is a feature of all speciose coral assemblages, including equatorial reefs. Nonetheless, considerable variation in reproductive synchrony exists among locations and the hypothesis that the extent of spawning synchrony is correlated with latitude has not been formally tested on a large scale. Here, we use data from 90 sites throughout the Indo-Pacific and a quantitative index of reproductive synchrony applied at a monthly scale to demonstrate that, despite considerable spatial and temporal variation, there is no correlation between latitude and reproductive synchrony. Considering the critical role that successful reproduction plays in the persistence and recovery of coral reefs, research is urgently needed to understand the drivers underpinning variation in reproductive synchrony.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many plants and animals breed seasonally during periods that are likely optimal for fertilisation success and the early development of offspring. In addition to reproductive seasonality, many species exhibit marked reproductive synchrony, i.e. reproduction occurring in tighter temporal clusters than would be expected by seasonality alone (Ims 1990a). Some examples include species of mast-seeding bamboos, which will grow during a species-specific period of between 3 and 120 years, before reproducing synchronously (Janzen 1976), and the Pacific Ridley turtle, which lays eggs during synchronous mass nestings called “arribadas” involving tens of thousands of individuals (Hughes and Richard 1974).

In addition to high reproductive synchrony within species, spawning events involving multiple species occur in fishes (Whaylen et al. 2004; Heyman and Kjerfve 2008), polychaetes (Hardege 1999), echinoderms (Himmelman et al. 2008) and frogs (Wilczynski et al. 1993). Multi-species synchronous spawning is also a feature of most species-rich coral assemblages (Babcock et al. 1986; Guest et al. 2005; Baird et al. 2009a). Intra-specific synchrony is likely highly adaptive for sessile, broadcast spawning marine invertebrates as a way to maximise fertilisation success (Ims 1990a). The adaptive significance of numerous species spawning at the same time is less clear. While several hypotheses have been proposed (e.g. predator satiation), the most parsimonious explanation is that species have responded similarly, but independently, to environmental signalling cues (e.g. sea surface temperatures (SSTs), lunar cycles, diel cycles) (Oliver et al. 1988).

One of the early predictions relating to spawning in corals was that multi-species spawning synchrony was correlated with latitude, with a breakdown in spawning synchrony near the equator, due to a lack of suitable cues related to the annual amplitude of environmental variables or lack of selective pressures to spawn at an optimal time of the year (Oliver et al. 1988; Olive 1995). While later work revealed that multi-species spawning synchrony was a feature of most diverse coral assemblages, including those on equatorial reefs (Guest et al. 2005), the original hypothesis that synchrony is correlated with latitude was never quantitatively tested on a global scale (but see Baird et al. 2009a). Much of the confusion with respect to geographical variation in coral spawning synchrony exists because synchrony is rarely quantified (Baird and Guest 2009). Quantitative estimates of synchrony are available and have been widely used to quantify flowering synchrony in plant assemblages (Post 2003; Elzinga et al. 2007; Freitas and Bolmgren 2008).

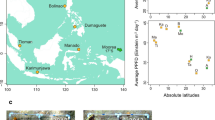

In this study, we use data from Acropora assemblages on 90 Indo-Pacific sites between the latitudes of 31.5°S and 27.2°N over a 20-year period and the Marquis index (Marquis 1988) to examine synchrony at the monthly scale within multi-species assemblages, within six individual species, and explore patterns in synchrony across multiple years at specific locations.

Materials and methods

The dataset

To explore patterns of coral spawning synchrony, we compiled a dataset of coral reproductive condition for Acropora (Fig. 1) from both published (i.e. Guest et al. 2005; Baird et al. 2009b, 2010, 2011, 2015; Rosser and Baird 2009; Hanafy et al. 2010; Raj and Edward 2010) and original data (see Online Resource 1). Coral reproductive condition was defined following Baird et al. (2002). To enable a rigorous comparison of synchrony, we only included surveys that, for each site, randomly sampled the entire Acropora assemblage, sampled at least 30 colonies in each month and we did not include sites with less than 50% cumulative spawning predicted in any one year, because it was assumed that the full spawning season had not been adequately captured. Synchrony was also examined in six species that were surveyed on at least 25 sites (n = 25 was chosen as a minimum for statistical robustness of correlation analyses (David 1938)), with at least 20 colonies sampled each month, and with greater than 50% cumulative spawning.

Species were identified in the field or from field images following Veron (2000). Due to current uncertainties in coral taxonomy, in particular in the genus Acropora (Cowman et al. 2020), the main analyses were run at the assemblage level, for which correct identifications are not necessary. For the species analysis, we chose six species that were common, widespread and relatively easy to identify. Nonetheless, we accept that these are taxa in which cryptic species are possible (Ladner and Palumbi 2012; Richards et al. 2016), suggesting these analyses might need to be revisited in the future. Uncertainties in the identifications are indicated by the use of a series of open nomenclature qualifiers (Bengtson 1988; Sigovini et al. 2016) that allow the assignment of a specimen to a nominal species with varying degrees of certainty. Specimens that closely resemble the type of a nominal species are given the qualifier cf. (e.g. Acropora cf. nasuta). Specimens that have morphological affinities to a nominal species but appear distinct are given the qualifier aff. (e.g. Acropora aff. pulchra): these specimens are either geographical variants of species with high morphological plasticity or undescribed species. Species that could not be matched with the type material of any nominal species were labelled as sp. with the image number (e.g. Acropora sp_81-4052). These specimens are most probably undescribed species. No individuals identified using open nomenclature qualifiers were used for the spatial analyses of reproductive synchrony within common Acropora species.

Predicting the month of spawning

In order to calculate the Marquis index, it was necessary to convert the coral reproductive condition data into the number of colonies spawning in each month of the year as follows. Mature colonies observed up to 6 days after the full moon were predicted to spawn in the same lunar month as the sampling date. In the few cases where mature colonies were observed 7 days or more after the full moon, they were predicted to spawn during the subsequent lunar month. The cut-off date was set at six nights after the full moon given that date is the peak night of spawning in Indo-Pacific Acropora assemblages (see Online Resource 2 for more details). Immature colonies were assumed to spawn a month later than mature colonies. We also considered that mature and immature colonies would not spawn again for up to two months after their predicted month of spawning. Indeed, gametogenic cycles require 6 to 14 months to complete (Baird et al. 2009a) and eggs that would be sufficiently mature to be released would be visible at least two months in advance. Similarly, we considered that empty colonies would not spawn for at least 60 days.

Quantifying reproductive synchrony: the Marquis index

Reproductive synchrony can be defined at several temporal levels (e.g. month, night or time of spawning) depending on the hypothesis being tested. Here, we define synchrony as the proportion of corals within a population or assemblage that are inferred to spawn in the same month based on the presence of mature (pigmented) or immature (white) gametes. We used the following index originally developed for flowering synchrony by Marquis (Marquis 1988) to quantify coral reproductive synchrony.

where t is the month of survey, n in the number of months surveyed, mt is the number of coral colonies predicted to spawn in month t, pt is the proportion of colonies examined in month t that are predicted to spawn and \(\sum\limits_{{{\text{t}} = 1}}^{{\text{t = n}}} {{\text{m}}_{{\text{t}}} }\)is the total number of coral colonies predicted to spawn during the period studied. The Marquis index of synchrony can take values from 0 (spawning spread evenly across the year) to 1 (spawning involving the entire population during each month of spawning, whether over a month or more). Marquis’ synchrony index was calculated at the assemblage level SM (A) to determine the synchrony among species and at the species level SM (S) to determine the intra-species synchrony and compare synchrony among species. Sites with multiple years of reproductive surveys were analysed per year, and yearly Marquis indices were averaged to produce one value per site unless mentioned otherwise. In regions where two spawning seasons exist, such as in Western Australia, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and Singapore, the Marquis index was calculated based on reproductive data from the entire year, to ensure a synchrony index based on the entire Acropora assemblage and to avoid overestimating synchrony when different individuals are involved in each spawning season.

Statistical analyses

Pearson’s correlation tests were conducted to examine the relationships between latitude and reproductive synchrony at both the assemblage level and at the species level. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for any difference in reproductive synchrony among Acropora species. Data were log-transformed where necessary to meet normality assumptions. Normality of residuals was verified visually or with a Shapiro–Wilk normality test. All statistical analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team 2019), with the R packages car (Fox and Weisberg 2019), dplyr (Wickam et al. 2019), ggplot2 (Wickham 2016), rcompanion (Mangiafico 2019), rnaturalearth (South 2017) and sf (Pebesma 2018).

Results

Reproductive synchrony of the Acropora assemblages was not correlated with latitude (Pearson’s correlation, r = 0.02, t(75) = 0.22, p = 0.83; Fig. 2), even when examined per year (Online Resource 3). High synchrony was found at both high latitudes (e.g. SM(A) = 0.89 at Ndigoro Reef in New Caledonia, 22.11°S) and low latitudes (e.g. SM(A) = 0.75 at Ahus 8 Reef, in Papua New Guinea, 1.91°S). Similarly, low synchrony was found at both latitude ranges (e.g. SM(A) = 0.28 at North Molle Reef, Whitsundays, Australia, 20°S, and SM(A) = 0.31 at Pulau Weh, Indonesia, 5.87°N).

Reproductive synchrony was not correlated with latitude in any of the six species examined (Fig. 3, Table 1). Both high and low reproductive synchrony was found at all latitudes, and within a given latitudinal range, there was high variability in reproductive synchrony (Fig. 3). For example, reproductive synchrony ranged between 0.36 and 0.85 in A. digitifera at 20°S (± 0.5°) and between 0.33 and 0.69 in A. hyacinthus at 20°S (± 0.5°). Average synchrony was similar across species (one-way ANOVA, F(5,197) = 1.55, p = 0.18, Fig. 3).

Reproductive synchrony was also variable on a temporal scale (Fig. 4). For example, at Magnetic Island (Australia), synchrony ranged from 0.37 (2005) to 0.50 (2017), at Orpheus Island (Australia), reproductive synchrony ranged from 0.24 (2012) to 0.70 (2016), and at Raffles Lighthouse (Singapore), reproductive synchrony ranged from 0.42 (2002 and 2011) to 0.68 (2009). Nonetheless, temporal variability in reproductive synchrony (can be quantified here by the standard deviation from the mean Marquis index at each location) did not follow any latitudinal trend (Pearson’s correlation, r = 0.34, t(7) = 0.95, p = 0.37).

Annual variability in spawning synchrony. From left to right: Magnetic Island, Australia, 19.1°S, n = 6; Orpheus Island, Australia, 18.6°S, n = 5; Pelorus Island, Australia, 18.6°S, n = 4; Lizard Island, Australia, 14.7°S, n = 5; Raffles Lighthouse, Singapore, 1.2°N, n = 5; Mainland Patch Reef, India, 8.7°N, n = 5; Kariyachalli Island, India, 8.9°N, n = 5; Sesoko, Japan, 26.6°N, n = 3; Oku, Japan, 26.9°N, n = 4

Discussion

No relationship was found between latitude and Acropora coral reproductive synchrony at the lunar month level. Instead, reproductive synchrony was highly variable on both spatial and temporal scales. These results support the only quantitative study of reproductive synchrony to date (i.e. Baird et al. 2009a), which found no consistent pattern between synchrony and latitude.

Our definition of reproductive synchrony is based on the proportion of mature colonies within each month of the year. We here define synchrony at a monthly scale given reproductive sampling efforts are currently mostly conducted on a monthly (lunar calendar) basis and because the resolution is sufficient to examine latitudinal patterns. Once reproductive patterns are better understood at the monthly level, similar indices for spawning synchrony, i.e. the proportion of individuals that spawn on any night, could also be determined. This will require extensive data on in situ spawning times (and absence of spawning) over an entire reproductive period but will allow for a deeper understanding of reproductive synchrony at a resolution that will provide insights into reproductive success or isolation among genotypes within a given species.

Recent work suggests a breakdown in spawning synchrony occurred over the last decades (Shlesinger and Loya 2019), with potential implications for fertilisation success. However, among other potential issues (see Guest et al. 2020 for more detail), no quantitative estimate of reproductive synchrony was used. The potential effects of climate change on coral reproduction are worrying (Mendes and Woodley 2002; Levitan et al. 2014; Hagedorn et al. 2016), but whether or not reproductive synchrony is affected will require the use of comparable quantitative data, such as is proposed here.

The lack of correlation between reproductive synchrony and latitude suggests that variation in synchrony is also not correlated with factors that vary predictably with latitude, such as range and amplitudes of SSTs and day length, which are marked at high latitudes and decrease towards the equator. This supports previous observations of marked reproductive synchrony in equatorial regions, where environmental variables show less variability throughout the year (Guest et al. 2005). We know that the range of change in temperature is a strong predictor in the peak month of spawning (Keith et al. 2016) but the driving forces responsible for variation in synchrony will most probably be challenging to identify, and might involve a combination of environmental constraints and adaptive strategies (Ims 1990a; Koenig et al. 2003). Similar challenges have been identified in ecological studies of large-scale masting synchrony in long-lived plant species (e.g. Koenig et al. 2003; Kelly et al. 2013; Pearse et al. 2014). For example, while the benefits of synchronising mast seeding in plant assemblages include predator satiation (Janzen 1971; Ims 1990b) and increased pollination efficiency in wind-pollinated species (Smith et al. 1990; Moreira et al. 2014), the proximate drivers remain elusive and challenging to identify (Kelly et al. 2013; Pearse et al. 2014).

Temporal variability in reproductive synchrony at any one site was considerable, and that variability was not linked with latitude. Nonetheless, that variability did not hide any latitudinal patterns in reproductive synchrony, which would have been visible when reproductive synchrony was examined in single years. The month(s) of spawning of different coral species in each region is generally reliable from one year to the next, but the exact dates of spawning vary as they are aligned with the lunar cycle. As such, in some years, instead of the peak spawning occurring within a single month, spawning can be split over two consecutive months (i.e. split spawning, Foster et al. 2018), thus decreasing spawning synchrony for that year. Some yearly variability in reproductive synchrony can be explained by the presence of a split spawning event, but other ecological factors are likely to be involved as well. For example, decreases in spawning synchrony may also occur in response to stress, such as following coral bleaching (Baird and Marshall 2002), or cyclones (Baird et al. 2018) disrupting timing cues and reducing reproductive output sometimes for years. Temporal variability in reproductive synchrony at each reef is likely further complicating the task of identifying the driving forces responsible for variation in spatial synchrony across the Indo-Pacific region. Further work is needed to identify temporal variability in other reefs and to determine how to incorporate annual variability in spatial analyses of reproductive synchrony.

Considering the importance of reproductive success to reef recovery and persistence, it is critical to examine spatial and temporal patterns in reproductive synchrony using quantitative approaches. In particular, long-term reproductive synchrony surveys are required to understand the possible long-term effects of climate change on spawning synchrony.

Change history

20 July 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-021-02149-z

References

Babcock RC, Bull GD, Harrison PL, Heyward AJ, Oliver JK, Wallace CC, Willis BL (1986) Synchronous spawnings of 105 scleractinian coral species on the Great Barrier Reef. Mar Biol 90:379–394

Baird AH, Guest JR (2009) Spawning synchrony in scleractinian corals: comment on Mangubhai & Harrison (2008). Mar Ecol Prog Ser 374:301–304

Baird AH, Marshall PA (2002) Mortality, growth and reproduction in scleractinian corals following bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 237:133–141

Baird AH, Marshall PA, Wolstenholme JK (2002) Latitudinal variation in the reproduction of Acropora in the Coral Sea. Proc 9th Int Coral Reef Symp 1:385–389

Baird AH, Guest JR, Willis BL (2009a) Systematic and biogeographical patterns in the reproductive biology of scleractinian corals. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 40:551–571

Baird AH, Birrell CL, Hughes TP, McDonald A, Nojima S, Page CA, Pratchett MS, Yamasaki H (2009b) Latitudinal variation in reproductive synchrony in Acropora assemblages: Japan vs. Australia Galaxea 11:101–108

Baird AH, Kospartov MC, Purcell S (2010) Reproductive synchrony in Acropora assemblages on reefs of New Caledonia. Pac Sci 64:405–412

Baird AH, Blakeway DR, Hurley TJ, Stoddart JA (2011) Seasonality of coral reproduction in the Dampier Archipelago, northern Western Australia. Mar Biol 158:275–285

Baird AH, Cumbo VR, Gudge S, Keith SA, Maynard JA, Tan C-H, Woolsey ES (2015) Coral reproduction on the world’s southernmost reef at Lord Howe Island, Australia. Aquat Biol 23:275–284

Baird AH, Álvarez-Noriega M, Cumbo VR, Connolly SR, Dornelas M, Madin JS (2018) Effects of tropical storms on the demography of reef corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 606:29–38

Bengtson P (1988) Open nomenclature. Palaeontology 31:223–227

Cowman PF, Quattrini AM, Bridge TC, Watkins-Colwell GJ, Fadli N, Grinblat M, Roberts TE, McFadden CS, Miller DJ, Baird AH (2020) An enhanced target-enrichment bait set for Hexacorallia provides phylogenomic resolution of the staghorn corals (Acroporidae) and close relatives. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 153:106944

David FN (1938) Tables of the ordinates and probability integral of the distribution of the correlation coefficient in small samples. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Elzinga JA, Atlan A, Biere A, Gigord L, Weis AE, Bernasconi G (2007) Time after time: flowering phenology and biotic interactions. Trends Ecol Evol 22:432–439

Foster T, Heyward AJ, Gilmour JP (2018) Split spawning realigns coral reproduction with optimal environmental windows. Nat Commun 9:718

Fox J, Weisberg S (2019) An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd edn. SAGE Publications Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA

Freitas L, Bolmgren K (2008) Synchrony is more than overlap: measuring phenological synchronization considering time length and intensity. Rev Bras Bot 31:721–724

Guest JR, Baird AH, Goh BPL, Chou LM (2005) Seasonal reproduction in equatorial reef corals. Invertebr Reprod Dev 48:207–218

Guest JR, Baird AH, Bouwmeester J, Edwards A (2020) Comment on Breakdown in spawning synchrony: a silent threat to coral persistence. Science eLetters. Available online: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/365/6457/1002/tab-e-letters

Hagedorn M, Carter VL, Lager C, Camperio Ciani JF, Dygert AN, Schleiger RD, Henley EM (2016) Potential bleaching effects on coral reproduction. Reprod Fertil Dev 28:1061–1071

Hanafy MH, Aamer MA, Habib M, Rouphael AB, Baird AH (2010) Synchronous reproduction of corals in the Red Sea. Coral Reefs 29:119–124

Hardege JD (1999) Nereidid polychaetes as model organisms for marine chemical ecology. Hydrobiologia 402:145–161

Heyman WD, Kjerfve B (2008) Characterization of transient multi-species reef fish spawning aggregations at Gladden Spit, Belize. Bul Mar Sci 83:531–551

Himmelman JH, Dumont CP, Gaymer CF, Vallières C, Drolet D (2008) Spawning synchrony and aggregative behaviour of cold-water echinoderms during multi-species mass spawnings. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 361:161–168

Hughes DA, Richard JD (1974) The nesting of the Pacific ridley turtle Lepidochelys olivacea on Playa Nancite, Costa Rica. Mar Biol 24:97–107

Ims RA (1990a) The ecology and evolution of reproductive synchrony. Trends Ecol Evol 5:135–140

Ims RA (1990b) On the adaptive value of reproductive synchrony as a predator-swamping strategy. Am Nat 136:485–498

Janzen DH (1971) Seed predation by animals. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 2:465–492

Janzen DH (1976) Why bamboos wait so long to flower. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 7:347–391

Keith SA, Maynard JA, Edwards AJ, Guest JR, Bauman AG, van Hooidonk R, Heron SF, Berumen ML, Bouwmeester J, Piromvaragorn S, Rahbek C, Baird AH (2016) Coral mass spawning predicted by rapid seasonal rise in ocean temperature. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 283:20160011

Kelly D, Geldenhuis A, James A, Penelope Holland E, Plank MJ, Brockie RE, Cowan PE, Harper GA, Lee WG, Maitland MJ (2013) Of mast and mean: differential-temperature cue makes mast seeding insensitive to climate change. Ecol Lett 16:90–98

Koenig WD, Kelly D, Sork VL, Duncan RP, Elkinton JS, Peltonen MS, Westfall RD (2003) Dissecting components of population-level variation in seed production and the evolution of masting behavior. Oikos 102:581–591

Ladner JT, Palumbi SR (2012) Extensive sympatry, cryptic diversity and introgression throughout the geographic distribution of two coral species complexes. Mol Ecol 21:2224–2238

Levitan DR, Boudreau W, Jara J, Knowlton N (2014) Long-term reduced spawning in Orbicella coral species due to temperature stress. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 515:1–10

Mangiafico S (2019) rcompanion: functions to support extension education program evaluation. R package version 2.3.7. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rcompanion

Marquis RJ (1988) Phenological variation in the neotropical understory shrub Piper arielanum: causes and consequences. Ecology 69:1552–1565

Mendes JM, Woodley JD (2002) Effect of the 1995–1996 bleaching event on polyp tissue depth, growth, reproduction and skeletal band formation in Montastraea annularis. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 235:93–102

Moreira X, Abdala-Roberts L, Linhart YB, Mooney KA (2014) Masting promotes individual-and population-level reproduction by increasing pollination efficiency. Ecology 95:801–807

Olive PJW (1995) Annual breeding cycles in marine invertebrates and environmental temperature: Probing the proximate and ultimate causes of reproductive synchrony. J Therm Biol 20:79–90

Oliver J, Babcock R, Harrison P, Willis B (1988) Geographic extent of mass coral spawning: clues to ultimate causal factors. Proc 6th Int Coral Reef Symp 2:803–810

Pearse IS, Koenig WD, Knops JM (2014) Cues versus proximate drivers: testing the mechanism behind masting behavior. Oikos 123:179–184

Pebesma E (2018) Simple features for R: standardized support for spatial vector data. R J 10:439–446

Post E (2003) Large-scale climate synchronizes the timing of flowering by multiple species. Ecology 84:277–281

R Core Team (2019) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

Raj KD, Edward JKP (2010) Observations on the reproduction of Acropora corals along the Tuticorin coast of the Gulf of Mannar, Southeastern India. Indian J Mar Sci 39:219–226

Richards ZT, Berry O, van Oppen MJ (2016) Cryptic genetic divergence within threatened species of Acropora coral from the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Conserv Genet 17:577–591

Rosser N, Baird A (2009) Multi-specific coral spawning in spring and autumn in far north-western Australia. Proc 11th Int Coral Reef Symp 1:366–370

Shlesinger T, Loya Y (2019) Breakdown in spawning synchrony: A silent threat to coral persistence. Science 365:1002–1007

Sigovini M, Keppel E, Tagliapietra D (2016) Open Nomenclature in the biodiversity era. Methods Ecol Evol 7:1217–1225

Smith CC, Hamrick J, Kramer CL (1990) The advantage of mast years for wind pollination. Am Nat 136:154–166

South A (2017) rnaturalearth: World Map Data from Natural Earth. R package version 0.1.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rnaturalearth

Veron JEN (2000) Corals of the world, vol I. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia

Whaylen L, Pattengill-Semmens C, Semmens B, Bush P, Boardman M (2004) Observations of a Nassau grouper, Epinephelus striatus, spawning aggregation site in Little Cayman, Cayman Islands, including multi-species spawning information. Environ Biol Fishes 70:305–313

Wickham H (2016) ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag, New York

Wickham H, François R, Henry L, Müller K (2019) dplyr: a grammar of data manipulation. R package version 0.8.3. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr

Wilczynski W, McClelland B, Rand A (1993) Acoustic, auditory, and morphological divergence in three species of neotropical frog. J Comp Physiol A 172:425–438

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (AHB), the Singapore National Research Foundation (AGB, MSRDP-P03) and King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) baseline research funding (MLB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Topic Editor Anastazia Teresa Banaszak

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bouwmeester, J., Edwards, A.J., Guest, J.R. et al. Latitudinal variation in monthly-scale reproductive synchrony among Acropora coral assemblages in the Indo-Pacific. Coral Reefs 40, 1411–1418 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-021-02129-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-021-02129-3