Abstract

Objective

The aim of this summary review is to analyse the current state of evidence in manual medicine or manual therapy.

Methods

The literature search focussed on systematic reviews listed in PubMed referring to manual medicine treatment until the beginning of 2022, limited to publications in English or German. The search concentrates on (1) manipulation, (2) mobilization, (3) functional/musculoskeletal and (4) fascia. The CASP Checklist for Systematic Reviews was used to present the included reviews in a clear way.

Results

A total of 67 publications were included and herewith five categories: low back pain, neck pain, extremities, temporomandibular disorders and additional effects. The results were grouped in accordance with study questions.

Conclusion

Based on the current systematic reviews, a general evidence-based medicine level III is available, with individual studies reaching level II or Ib. This allows manual medicine treatment or manual therapy to be used in a valid manner.

Zusammenfassung

Ziel

Ziel der vorliegenden Übersichtsarbeit war eine Auswertung des aktuellen Erkenntnisstands in der manuellen Medizin bzw. in der manuellen Therapie.

Methoden

Bei der Literatursuche lag der Fokus auf systematischen Übersichten, begrenzt auf die Sprachen Englisch oder Deutsch, die bis Anfang 2022 in der Datenbank PubMed vorhanden waren und sich auf die Behandlung mittels manueller Medizin bezogen. Die Suche umfasste die Begriffe (1) „manipulation“, (2) „mobilization“, (3) „functional/musculoskeletal“ und (4) „fascia“. Die Checkliste für systematische Übersichten gemäß Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) wurde verwendet, um die einbezogenen Übersichtsarbeiten auf eine übersichtliche Weise zu präsentieren.

Ergebnisse

In die Auswertung wurden 67 Publikationen eingeschlossen, die in 5 Kategorien unterteilt waren: Schmerzen des unteren Rückens, Nackenschmerzen, Extremitäten, temporomandibuläre Störungen und sonstige Auswirkungen. Die Ergebnisse wurden in Übereinstimmung mit den Fragestellungen der Studie gruppiert.

Schlussfolgerung

Auf der Grundlage aktueller systematischer Übersichtsarbeiten liegt eine allgemeine Evidenz der Stufe III vor, dabei erreichten einzelne Studien sogar Stufe II oder Ib. Diese Ausgangssituation ermöglicht eine valide Behandlung mit manueller Medizin oder manueller Therapie.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

In recent years, the European Scientific Society of Manual Medicine (ESSOMM) has developed “the European core curriculum and principles of manual medicine” (MM) [40]. Many authors from all of the member countries of ESSOMM have contributed substantially to the important issues. They state in their introduction: “The techniques and methods of manual medicine are diverse and innumerable, therefore, it was necessary to delineate the scientific background in anatomy and physiology on which they were based, to gather proof of their effectiveness in reported clinical studies and to identify the positioning of manual medicine in complex clinical therapeutic regimens” [40].

MM consists of “manual diagnostic examination of the locomotor system, the head and connective tissue structures and of manual techniques to treat reversible dysfunction and the pain associated with it aiming to prevention, cure and rehabilitation. Diagnostic and therapeutic procedures are based on scientific neurophysiological and biomechanical principles” [40].

The procedures described in this curriculum relate specifically to investigating and treating tension and pain in muscles, joints and connective tissues as well as structures located within these tissues. The main goal of the therapeutic techniques is to eliminate or reduce movement restrictions and pain.

In Germany, MM is practiced by doctors specialized in this field and as “manual therapy” (MT) by physical therapists (PT). In the United States of America, MM is taught and practiced by doctors of osteopathy (DO). The German Society of Manual Medicine (DGMM) considers osteopathy as a part and an extension of MM. Chiropractic, as a form of so-called complementary medicine, aims also on motor dysfunction and pain in the movement system. In the USA, osteopathy is taught at universities offering a DO degree. In Europe, MM is taught through non-academic seminars whose teachers and, to a large extent, their graduates are organized into national scientific societies. MT is also taught through schools run by professional physical therapy organizations. The criteria and rules for training and further education in MM and MT are specified and controlled by the medical association and the health insurance companies. In contrast, there are no such controlled rules for training in osteopathy and it is taught, learned and used by doctors, PT, and lay people alike. On this inconsistent basis, there are a variety of different textbooks, most of which were written by experienced users of MM. Greenman’s book “Principles of Manual Medicine” can be considered as a basic textbook in MM, which received the title Lehrbuch der osteopathischen Medizin in the German translation [23, 24].

MM, MT and osteopathy are now widely used worldwide as proven conservative methods in the treatment of functional limitations and pain in the musculoskeletal system. However, the terms MM, osteopathy and MT are used inconsistently and promiscuously. This inconsistency is reflected by a wide spectrum in the different variables of clinical practice:

-

Techniques for treatment are commonly described as manipulation, mostly as a thrust (impulse) with high velocity and low amplitude (HVLA technique); mobilization, as passive, mostly repeated movement by traction and/or rotation, e.g. joint mobilization; soft tissue techniques or muscle energy techniques, as massage-like techniques, e.g. “strain–counter strain” and others.

-

The specific path and level of training and skills of the acting people, i.e. physicians, physical therapists, osteopaths, chiropractors, laymen.

-

The spectrum of diagnosed and treated complaints and disorders:

-

Pain: low back pain (LBP), neck pain (NP), headache, muscle or joint pain.

-

Restricted spine or joint movement (hypomobility), hypermobility, elevated muscle tone.

-

In the past three decades, a growing number of case reports, retrospective analyses and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have accumulated in the literature, which has also resulted in a greater number of published systematic reviews. The authors of these studies are looking for answers about the strength and effectiveness of their MM-based intervention. This is mostly done directly or in comparison versus an alternative treatment. The outcomes are discussed very differently. The focus is on the special conditions of the execution of the treatment in the context of study quality, as well as on the criteria for the statement about the evidence.

Because there have been a large number of reviews on this problem in recent years, it is our goal to analyse the current state of evidence in MM based on the available reviews regarding the varying influencing factors on the effects of MM and MT treatment. The aim of this summarizing review is to give an overview of the current state of evidence for hands-on techniques, independent of special techniques or localization of complaints.

Methods

The aim of this summarizing review is to gain a picture of the level of evidence in MM. For this purpose, a corresponding literature search was conducted in autumn 2019 using the PubMed database. In order to keep the review up to date, the literature search was repeated at the beginning of 2022. In this way, numerous reviews could be added.

The search strategy included various terms, which were divided into four categories:

-

First category, manipulation: spinal manipulation OR manipulation thrust OR HVLA OR high-velocity low-amplitude OR HVT OR high-velocity thrust OR OMT OR osteopathic manipulative treatment OR manipulation with impulse OR musculoskeletal manipulation.

-

Second category, mobilization: (mobilization OR mobilization) AND (manual OR joint OR spine OR extremity)

-

Third category, functional/musculoskeletal: (“manual medicine” OR “manual therapy”) and (functional OR musculoskeletal OR disorder)

-

Fourth category, fascia: (“manual medicine” OR “manual therapy”) AND (fascia OR myofascial OR neurofascial)

The search was limited to the last 10 years, to studies with humans and to full texts of clinical studies and reviews in German or English language.

First, the literature was narrowed down by title. The second step in the selection process was to review the available abstracts. Furthermore, only the reviews were extracted from this large number of hits, in order to avoid duplication of content that had already been summarized.

In addition, a free search was carried out on the topic of manual therapy in subject-specific databases of the Dutch manual medicine association and the Ärztevereinigung Manuelle Medizin, Berlin, whereby here, again, only reviews were included into the overview.

To sum up, publications were included if they address manual medicine or manual therapy treatment in an original manner and if they were presented as a systematic review. Studies were excluded if they concentrate on concomitant factors like cost effectiveness or topics other than therapy. Furthermore, single trials, conference papers and so on were ruled out.

Currently, there is no systematically developed reporting guideline for overviews [56]. The CASP Checklist for Systematic Reviews was used to present the studies found in a meaningful and clear way [7]. It must be emphasized that the aim of this checklist is not to evaluate the included research. Rather, the three sections of the CASP checklist support answering of the questions about validity, the results and the consequences that can be drawn for clinicians and researchers. Therefore, the referring tables can be found in the supplementary material.

Two reviewers extracted the data regarding target/treatment, the used assessments, the studies included and the found outcome. Furthermore, the CASP scale was used by both, to allow a better overview. Disagreements were resolved by a third opinion.

Results

Search results

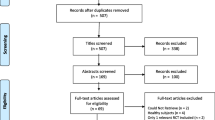

With the chosen search strategy, 4720 hits were obtained in the specialist literature via the PubMed database and an additional free search. Screening the records by title and abstract left 378 hits. To concentrate on realistic and generally valid statements concerning the evidence of MM or MT, only the reviews were selected (n = 88). The published papers were assessed for eligibility, with a final number of 67 records; 21 reports had to be excluded for different reasons, e.g. topics other than therapy, focus on cost effectiveness or the small number of included studies, etc.

The remaining studies could be divided into five categories: 1) low back pain (LBP) with n = 17 reviews, neck pain (NP) with n = 12 reviews, extremities with n = 11 reviews, temporomandibular disorder (TMD) with n = 8 reviews and additional or other effects with n = 19 reviews. The literature search is illustrated in Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews. (From [51]

Low back pain

From the reviews found and selected, we classified 18 publications in the group “treatment of LBP with MM” [14, 18, 20,21,22, 26, 33, 34, 38, 39, 48, 50, 52, 59, 64, 65, 71, 72], where 11 of them described the treatment of unspecific LBP with HVLA [21], spinal manipulation [18, 33, 59] or spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) [50, 52, 59, 64, 65]. Other manual treatments are qualified as mobilization [14, 38, 59], manual therapy [20, 22, 39, 48] or other hands-on treatments, e.g. myofascial release or osteopathic manipulative treatment [48, 72]. The term “manual therapy” is inconsistently used for all hands-on interventions. Three reviews were targeted to MM in pregnancy-related LBP and pelvic pain [26, 71, 72], and one review to pain and disability caused by symptomatic lumbar spine stenosis [34].

Table 1 gives a summary of the treatment and intention of treatment, the assessments and included studies, and a summary of the results. Outcome in pain reduction is proved by a visual analogue scale (VAS) or numeric rating scale (NRS), functional enhancement by questionnaires such as the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire, Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire or Short Form-36 Health Survey; occasionally by range of motion (ROM). The reviews that focused on non-specific LBP included up to 46 [20] studies, most more than 10 studies. One review has a summary of 6000 patients [59]. The quality of the studies evaluated in the reviews was not sufficient for meta-analysis, or meta-analysis could not include all studies from the review [65] because of deficits due to study quality.

The outcomes of SMT or MT are described as “to offer significant benefits in management of pain and function” [18, 33, 39, 52, 64], “to be better than usual medical care” as well as “short-term effects on pain relief and functional status” or significant benefit up to 6 weeks. One review with 26 RCTs and about 6000 participants in total [59] demonstrated high-quality evidence that spinal manipulation therapy in non-specific LBP has a statistically significant short-term effect on pain relief and functional status in comparison with other interventions. Evidence suggests that SMT causes neurophysiological effects (local hypoalgesia, sympathoexcitation, improved muscle function) [38, 50, 59]. Spinal manipulation in addition to general practitioner care was relatively cost effective [18, 20, 33]. The reviews support that “manipulative treatment should be part of musculoskeletal rehabilitation of LBP” [22].

No serious aversive events were reported.

Ten studies with 1198 pregnant women suffering from LBP and pelvic girdle pain report “limited evidence to support the use of MT on pain intensity as an option during pregnancy” [26, 72] whereas SMT “showed a significant effect on reducing pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea” [1], with the shortfall that not all studies reported dosage or session duration. Chiropractic care in postpartum LBP was not identified as a treatment option.

Studies in lumbar spine stenosis “showed better results in surgery for pain, disability and quality of life when continued conservative treatment has failed for 3 to 6 months” [34].

Neck pain

From the reviews found and selected, we classified 12 publications in the group “treatment of NP with MM” [11, 12, 16, 19, 25, 28, 30, 36, 47, 61, 75, 76]. NP is described as non-specific, mechanical or cervicogenic NP with or without headache or radicular findings. One review focused on cervicogenic dizziness treated with HVLA or mobilization [42]. Table 2 gives a summary of the treatment and intention to treat, the assessments and included studies, and a summary of the results. Measurement of the results in pain reduction and functional improvement is by VAS, cervical ROM, NRS, neck pain questionnaire and/or dizziness handicap inventory. The 11 reviews that focused on NP included 3 to 23 studies.

Manual interventions consisted mostly of manipulation (with or without thrust), mobilization or myofascial techniques. The term “manual therapy” is inconsistently used for all hands-on interventions.

Two reviews including 23 RCTs with 680 patients with acute NP and 929 patients with chronic NP [28] and six studies with around 600 patients [61] stated positive effects for HVLA as statistically significant and clinically relevant improvements for pain and disability immediately and for up to 1 week to 6 months.

Two large reviews [25, 47], both from the same research group, included 1400 and 1900 patients. In their conclusions they state a “support for combined mobilization, manipulation and exercise for short-term pain reduction” and found “low-quality evidence suggesting manipulation, mobilization and exercise to produce greater long-term pain reduction compared to no treatment and low-quality evidence for improvement in function” [47] and concluded “moderate-quality evidence after cervical manipulation and mobilization for similar effects on pain, function and patient satisfaction at intermediate-term follow-up than in control group” [25]. These findings are congruent with the outcome of the other reviews [12, 16, 19, 30]. It is mentioned that “outcome is consistent with evidence from previous systematic reviews” [28]. A long-term follow-up with low-quality evidence shows a non-significant difference between spinal manipulative treatment and other manual therapies [16]. The treatment period is reported mostly up to several weeks and follow-up-until 1 year. No serious adverse events were reported.

There is “moderate evidence in a favourable direction to support the use of HVLA or mobilization for cervicogenic dizziness” [42].

Temporomandibular disorder

Eight of the reviews found belong to the category “treatment of temporomandibular (joint) disorder (TMD) with MM” [3, 6, 19, 29, 37, 43, 46, 69]. The symptoms to treat are also called orofacial (myogenous and arthrogenous) disorder, sometimes accompanied by headache or myofascial pain. The intention of treatment is referred to as “orofacial myofunctional therapy” in these reviews [29]. One review included treatment of cardiovascular performance with C5/C5 HVLA manipulation [19].

Table 3 summarizes the treatments and intention of treatment, the assessments, included studies and results. The results were evaluated by VAS, maximal mouth opening (MMO) and pain pressure threshold (PPT). The eight reviews comprise 95 studies with about 2000 patients. These reviews report mostly a high risk of bias.

The outcomes are shown as evidence of orthopaedic manual therapy (OMT) in correcting “dentofacial deformities when combined with orthodontic treatment” [6, 29, 37, 43], “greater MMO (high evidence) [6], pain (moderate evidence) and PPT, compared to a usual care group”, “MT targeted to the cervical spine decreased pain and increased mouth ROM” [3, 19, 37] and “significant large effect on active mouth opening and on cervicogenic headaches” [43]. In subjects with hypertension, blood pressure seemed to decrease after cervical HVLA manipulation [19].

Upper and lower extremities

Eleven of the publications found were assignable to the category “treatment of pain and dysfunctions in upper or lower extremities with MM” [2, 5, 15, 27, 41, 45, 54, 55, 60, 67, 74]: three reviews focused on knee osteoarthritis (KOA) [60, 67, 74], one on plantar heel pain [55], one on lateral ankle sprains [41], two on thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis [5, 27] and three further reviews on shoulder or elbow [2, 54] or on MT for rotator cuff tendinopathy [15]. Table 4 gives a summary of the treatments with the intention of treatment, the assessments, the included studies and the results. Outcome is measured with VAS or other NRS, ROM, and WOMAC for KOA, regional typical functional tests and/or electromyography. The reports on KOA are based on 32 studies with more than 1000 patients. MT is meant as technique with contact to the soft tissues, bones, and joints, often “individualized based on examination findings” [60]. Results of treatment are described as preliminary evidence: “manual therapy significantly relieves pain, significantly improves physical function for > 4 weeks [74], specifically as an adjunct to another treatment and versus comparators of no treatment” [60]. Regarding the long-term benefits of MT, the research findings were inadequate for making safe and reliable conclusions [67].

For MT containing joint manipulation in glenohumeral cuff tendinopathy, a “small but statistically significant overall effect for pain reduction compared with a placebo or in addition to another intervention” could be reported [15], whereas spinal manipulation on shoulder and upper limb pain “is not as effective as local treatment in reducing upper limb pain”.

For upper limb pain, the overall quality of evidence was very low; no strong recommendations can be made for the use of spinal manipulation (SM) in these patients [2]. In patients with lateral epicondylalgia, cervical HVLA manipulation resulted in increased pain-free handgrip [19].

The reviews on carpal tunnel syndrome or thumb carpometocarpal osteoarthritis showed a short-term improvement of function with pain relief when MT was combined with therapeutic exercise [5] and also better outcome when compared with electrotherapy [27].

Additional effects of manual medicine treatment

Of the reviews found and selected, we classified 19 publications in the group of reviews searching for additional treatment effects after applying MM. Four reviews searched for changes in biochemical markers or for influence on the autonomic nervous system (ANS) after mobilization or MT [35, 49, 57, 58]. Outcome was measured with biochemical markers (neuropeptides, inflammatory and endocrine biomarkers from blood, urine or saliva) or via cardiovascular parameters, skin conductance or skin temperature. One reason that there are many studies referring to effects accompanying MM- and MT-induced pain relief and motor function improvement (> 60) may be the insufficient knowledge about the mechanisms of MM treatment. On the other hand, the connections between pain, inflammatory activity and stress response suggest that changes triggered here can be measured—since pain itself is a subjective phenomenon.

Changes in cardiac parameters were expected when acting on the cervical or thoracic spine. Moderate-quality evidence on influencing biochemical markers is described, but was only followed up for a short time: modulation of pain and inflammation is possible, but without a statement on clinical importance [35] Results of OMT and MT are scarce in subjects, heterogeneous and limited in the methodological quality. No conclusive statement about influencing the ANS by cranial OMT can be reported, there may be responders and non-responders [57]. No declaration can be made on whether a certain treatment in an area can have more influence on the sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous system.

Two reviews focus on pelvic manual treatment. One shows significant evidence of pain reduction in primary dysmenorrhea [1]. The results of the second review including 18 studies might not necessarily apply to sustained application of external pelvic compression [4].

Two reviews show significant treatment effects of myofascial techniques on ROM and pain [70] and reduction of tender points [73].

One review found preliminary evidence supporting the effectiveness of subgroup-specific manual therapy in LBP, mostly in the short-term range [63].

Two reviews looked for the effect of manipulation and MT on vertigo and unsteadiness. 31 studies used balance tests, stabilography and a dizziness handicap inventory. The results show no correlation between pain reduction and stability, which limits the ability to generalize [32, 66].

Few studies are devoted to fibromyalgia [62, 68]. They are heterogeneous and usually only examine short-term effects. Results are insufficient to support and recommend the use of manual therapy.

One review (five studies) reports a positive effect on upper limbs and the thorax of female breast cancer survivors. MT decreased chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity and increased pain pressure threshold [13].

Nine studies focused on the effects of MT on the diaphragm. An immediate significant short-term effect on parameters related to costal, spinal and posterior muscle chain mobility could be shown [17].

Manual therapy is not significantly different to no treatment in terms of reducing fear-avoidance in individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain [31].

No clinical studies support or refute the efficacy or effectiveness of SMT in preventing the development of infectious disease or improving disease-specific outcomes [8].

To date, there is no evidence for an effect of SMT in the management of non-musculoskeletal disorders including infantile colic, childhood asthma, hypertension, primary dysmenorrhea and migraine [10].

There are no studies measuring the incidence or association of cervical spine manipulation and internal carotid artery dissection [9]. Table 5 summarizes the treatments and intention of treatment, the assessments, included studies and results.

Manual medicine treatments, especially myofascial techniques, are common and effective in a variety of complaints, e.g. in conditions after breast cancer or with fibromyalgia, dysmenorrhea, migraine, hypertension, infantile colitis, asthma or balance disorders—MM does not prevent their occurrence, but is helpful and facilitates in the management of several diseases.

Manual therapy influences the range of motion, pain intensity, flexibility and parts of the autonomic nervous system.

However, the level of heterogeneity between studies concerning intervention, outcome measures, comparison groups and implementation makes it difficult to draw consistent conclusions and give binding recommendations.

Diversity of research objectives

It is the aim of this summarizing review to evaluate the level of evidence for treatment with specific methods of MM for pain and functional disorders in the musculoskeletal system. The distribution of the keywords used for the search strategy describing the content of the evaluated literature is shown in Fig. 2. Manipulation and mobilization give 45%, MT results in 25%, and other manual or non-manual techniques add up to 30% of the keywords. Paying attention to the fact that the included reviews were published in about 30 different journals, these results speak for different intentions and aims of the single reviews. This is underlined by an even broader spread in the so-called clearly focused questions targeted to different complaints: LBP and NP together result in 44%, extremity pain is about 16% and TMD adds up to 12% of the questions. Other targets are fascia, muscles, vegetative or physiological effects, as shown in Fig. 3.

Discussion

The quality of the studies integrated into a review is based on proven criteria for assessing a risk of bias. The weakest points in almost all studies are blinding of patients and care providers (treating person, outcome-assessors) and selective reporting. Not all studies reported session duration of treatments [26]. Cross et al. (2011) stated “it is impossible to blind the care provider in manual treatments and, when self-reported measures are used, the trials do not meet the observer blinding criteria” [11]. Only a few trials avoided co-intervention [11]. One criterion, which upgrades the body of evidence, is a large amplitude of effects. An overall strength of “high” means we have high confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect and further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimation of the effect [64]. Quality decreases by inadequate execution and reporting, by the large and non-quantified variation in the spinal manipulation, and by the unknown heterogeneity of LBP patients [18, 21, 59]. There are a great number of studies which report that the manual techniques are provided by persons skilled and experienced in manual medicine treatment techniques and show a high intra- and interrater reliability, equivalent to high quality in the provided treatment variations.

Again, it should be particularly emphasized that adequate execution of both the examination and the treatment techniques is a combination of haptic and fine motor perception abilities. These skills are only perfected in a motor learning process in practical lifelong everyday activity. There are a large number of factors and variables influencing the success of MM. However, we do not think that this is fundamentally different from the conditions in other clinical disciplines.

Concentrating on the form used to describe treating pain and discomfort in the musculoskeletal system in the different parts of the body, it is noticeable that we not only encounter different treatment techniques but also differently qualified therapists and treatment providers, named as practitioners, doctors, manual medicine specialists, osteopaths, chiropractors and physiotherapists. One reason for this may be that there are different occupational titles and training paths in the single countries. The included studies are mostly in English language, some in Spanish or Portuguese, but the authors are from all over the world. There is also a great variety in the applied techniques described: different forms of MT, SMT, manipulation therapy, manipulation, HVLA, spine thrust, mobilization, hands-on therapy, physical therapy, osteopathic manipulative treatment, etc. With few exceptions, the individual treatment methods are not defined. The biggest shortcoming, however, is the missing description of the treatment carried out, the sequence and duration of treatment, and the procedure of the treatment technique itself. This makes it extremely difficult to compare treatments from different studies and prevents the studies from being repeated by other investigators for verification.

Masic et al. stated in 2008: “Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is the conscientious, explicit, judicious and reasonable use of modern, best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. EBM integrates clinical experience and patient values with the best available research information. … The practice of evidence-based medicine is a process of lifelong, self-directed, problem-based learning in which caring for one’s own patients creates the need for clinically important information about diagnosis, prognosis, therapy and other clinical and health care issues. It is not a ‘cookbook’ with recipes, but its good application brings cost-effective and better health care. The key difference between evidence-based medicine and traditional medicine is not that EBM considers the evidence while the latter does not. Both take evidence into account; however, EBM demands better evidence than has traditionally been used” [44].

In regular meetings of the MM societies, academies, teachers and expert commissions, opinions and convictions from clinical experience are agreed on and published in relevant international journals. This corresponds to level IV of the evidence classes according to the recommendations of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). A higher level of evidence is dependent on methodologically high-quality non-experimental studies such as comparative studies, correlation studies or case–control studies (level III) and on methodologically high-quality non-experimental studies such as comparative studies, correlation studies or case–control studies (level III) and high-quality studies without randomization (level IIb) as well as sufficiently large, methodologically high-quality RCTs (level Ib).

The levels are explained as follows [47]:

-

High quality of evidence: further research is unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. There are consistent findings among 75% of RCTs with a low risk of bias that can be generalized to the population in question. There are sufficient data, with narrow confidence intervals. There are no known or suspected reporting biases. (All of the domains are met).

-

Moderate quality of evidence: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. (One of the domains is not met).

-

Low quality of evidence: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. (Two of the domains are not met).

-

Very low quality of evidence: we are very uncertain about the estimate. (Three of the domains are not met).

Prerequisites for evidence-based diagnostics in MM are good reproducibility, validity, sensitivity and specificity studies of the diagnostic procedures. To ensure the quality of such studies, the International Academy for Manual Musculoskeletal Medicine has developed a “reproducibility protocol for diagnostic procedures in MM” in recent years. “The protocol can be used as a kind of ‘cook book format’ to perform reproducibility studies with kappa statistics. It makes it feasible to perform reproducibility studies in MM clinics and by educational boards of the MM societies” [53].

Conclusion

Based on the available scientific material, it can be concluded that a general EBM level III is available, with individual studies reaching level II or Ib, which creates the prerequisite and the ability to perform tasks to a satisfactory or expected verification (validity) of MM diagnostic and therapeutic techniques.

The results of this systematic review show that

-

Spinal manipulation and mobilization and MT were significantly more efficacious for neck/low back pain than no treatment, placebo, physical therapy or usual care in reducing pain.

-

SMT is a cost-effective treatment to manage spinal pain when used alone or in combination with general practitioner (GP) care or advice and exercise compared to GP care alone, exercise or any combination of these.

-

SMT has a statistically significant association with improvements in function and pain improvement in patients with acute low back pain.

-

Preliminary evidence that subgroup-specific manual therapy may produce a greater reduction in pain and increase in activity in people with LBP when compared with other treatments. Individual trials with a low risk of bias found large and significant effect sizes in favour of specific manual therapy.

-

Upper cervical manipulation or mobilization and protocols of mixed manual therapy techniques presented the strongest evidence for symptom control and improvement of maximum mouth opening.

-

Musculoskeletal manipulation approaches are effective for the treatment of temporomandibular joint disorders—here is a larger effect for musculoskeletal manual approaches/manipulations compared to other conservative treatments for temporomandibular joint disorder.

-

MM is helpful and facilitating in the management of several diseases, with an influence on range of motion, pain intensity, flexibility and parts of the autonomic nervous system.

The results of the available reviews and the evidence found on the effect of manual medicine treatment with the view to inclusion of manual therapy in guidelines are regarding treatment of acute and chronic pain due to the musculoskeletal system, especially including spine, joints and muscles.

All reviews mentioned call for further qualitative studies in order to consolidate and increase the level of evidence.

The previous initial shortcomings of the studies must be overcome:

-

Clear elaboration of questions.

-

Exact description of manual medicine practice/manual techniques.

-

Lowering the bias in patient inclusion.

The EBM-oriented physicians and therapists of tomorrow’s manual medicine treatment have three tasks [44]:

-

To use evidence summaries in clinical practice.

-

To help develop and update selected systematic reviews or evidence-based guidelines in their area of expertise.

-

To enrol patients in studies of treatment, diagnosis and prognosis on which medical practice is based.

The topicality of this statement has not changed to this day.

Abbreviations

- ANS:

-

Autonomic nervous system

- DGMM:

-

German Society of Manual Medicine

- EBM:

-

Evidence-based medicine

- ESSOMM:

-

European Scientific Society of Manual Medicine

- HVLA:

-

High-velocity low-amplitude

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- MM:

-

Manual medicine

- MT:

-

Manual therapy

- NP:

-

Neck pain

- NRS:

-

Numeric rating scale

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- OMT:

-

Orthopaedic manual therapy

- PPT:

-

Pain pressure threshold

- PT:

-

Physical therapists

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- ROM:

-

Range of motion

- SMT:

-

Spinal manipulative therapy

- TMD:

-

Temporomandibular disorder

- TMJ:

-

Temporomandibular joint

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Abaraogu UO, Igwe SE, Tabansi-Ochiogu CS, Duru DO (2017) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of manipulative therapy in women with primary dysmenorrhea. Explore 13(6):386–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2017.08.001

Aoyagi M, Mani R, Jayamoorthy J, Tumilty S (2015) Determining the level of evidence for the effectiveness of spinal manipulation in upper limb pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Man Ther 20(4):515–523

Armijo-Olivo S, Pitance L, Singh V, Neto F, Thie N, Michelotti A (2016) Effectiveness of manual therapy and therapeutic exercise for temporomandibular disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther 96(1):9–25

Arumugam A, Milosavljevic S, Woodley S, Sole G (2012) Effects of external pelvic compression on form closure, force closure, and neuromotor control of the lumbopelvic spine—a systematic review. Man Ther 17(4):275–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2012.01.010

Bertozzi L, Valdes K, Vanti C, Negrini S, Pillastrini P, Villafane JH (2015) Investigation of the effect of conservative interventions in thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil 37(22):2025–2043

Calixtre LB, Moreira RF, Franchini GH, Alburquerque-Sendín F, Oliveira AB (2015) Manual therapy for the management of pain and limited range of motion in subjects with signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorder: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. J Oral Rehabil 42(11):847–861

CASP Checklist 10 questions to help you make sense of a systematic review. https://casp-uk.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Systematic-Review-Checklist-2018_fillable-form.pdf. Accessed 23 Sept 2021

Chow N, Hogg-Johnson S, Mior S, Cancelliere C, Injeyan S, Teodorczyk-Injeyan J, Cassidy JD, Taylor-Vaisey A, Côté P (2021) Assessment of studies evaluating spinal manipulative therapy and infectious disease and immune system outcomes: A systematic review. JAMA Netw Open 4(4):e215493–e215493

Chung CLR, Côté P, Stern P, L’Espérance G (2015) The association between cervical spine manipulation and carotid artery dissection: a systematic review of the literature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 38(9):672–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.09.005

Côté P, Hartvigsen J, Axén I, Leboeuf-Yde C, Corso M, Shearer H, Wong J, Marchand A‑A, Cassidy JD, French S (2021) The global summit on the efficacy and effectiveness of spinal manipulative therapy for the prevention and treatment of non-musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Chiropr Man Therap 29(1):1–23

Cross KM, Kuenze C, Grindstaff T, Hertel J (2011) Thoracic spine thrust manipulation improves pain, range of motion, and self-reported function in patients with mechanical neck pain: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 41(9):633–642

Cumplido-Trasmonte C, Fernández-González P, Alguacil-Diego I, Molina-Rueda F (2021) Manual therapy in adults with tension-type headache: a systematic review. Neurologia 36(7):537–547

Da Silva FP, Moreira GM, Zomkowski K, de Noronha MA, Sperandio FF (2019) Manual therapy as treatment for chronic musculoskeletal pain in female breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 42(7):503–513

Dal Farra F, Risio RG, Vismara L, Bergna A (2021) Effectiveness of osteopathic interventions in chronic non-specific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med 56:102616

Desjardins-Charbonneau A, Roy J‑S, Dionne CE, Frémont P, MacDermid JC, Desmeules F (2015) The efficacy of manual therapy for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 45(5):330–350

Fernandez M, Moore C, Tan J, Lian D, Nguyen J, Bacon A, Christie B, Shen I, Waldie T, Simonet D (2020) Spinal manipulation for the management of cervicogenic headache: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pain 24(9):1687–1702

Fernández-López I, Peña-Otero D, de los Ángeles Atín-Arratibel M, Eguillor-Mutiloa M (2021) Effects of manual therapy on the diaphragm in the musculoskeletal system: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 102(12):2402–2415

Furlan AD, Yazdi F, Tsertsvadze A, Gross A, van Tulder M, Santaguida L, Gagnier J, Ammendolia C, Dryden T, Doucette S (2012) A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and safety of selected complementary and alternative medicine for neck and low-back pain. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/953139

Galindez-Ibarbengoetxea X, Setuain I, Andersen LL, Ramirez-Velez R, González-Izal M, Jauregi A, Izquierdo M (2017) Effects of cervical high-velocity low-amplitude techniques on range of motion, strength performance, and cardiovascular outcomes: a review. J Altern Complement Med 23(9):667–675

Gianola S, Bargeri S, Del Castillo G, Corbetta D, Turolla A, Andreano A, Moja L, Castellini G (2022) Effectiveness of treatments for acute and subacute mechanical non-specific low back pain: a systematic review with network meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 56(1):41–50

Goertz CM, Pohlman KA, Vining RD, Brantingham JW, Long CR (2012) Patient-centered outcomes of high-velocity, low-amplitude spinal manipulation for low back pain: a systematic review. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 22(5):670–691

Gomes-Neto M, Lopes JM, Conceição CS, Araujo A, Brasileiro A, Sousa C, Carvalho VO, Arcanjo FL (2017) Stabilization exercise compared to general exercises or manual therapy for the management of low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport 23:136–142

Greenman PE (2003) Principles of manual medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Greenman PE (2005) Lehrbuch der osteopathischen Medizin: mit 8 Tabellen. Thieme

Gross A, Miller J, D’Sylva J, Burnie SJ, Goldsmith CH, Graham N, Haines T, Brønfort G, Hoving JL (2010) Manipulation or mobilisation for neck pain: a Cochrane Review. Man Ther 15(4):315–333

Hall H, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Ward L, Adams J, Moore C, Sibbritt D, Lauche R (2016) The effectiveness of complementary manual therapies for pregnancy-related back and pelvic pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000004723

Hernández-Secorún M, Montaña-Cortés R, Hidalgo-García C, Rodríguez-Sanz J, Corral-de-Toro J, Monti-Ballano S, Hamam-Alcober S, Tricás-Moreno JM, Lucha-López MO (2021) Effectiveness of conservative treatment according to severity and systemic disease in carpal tunnel syndrome: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(5):2365

Hidalgo B, Hall T, Bossert J, Dugeny A, Cagnie B, Pitance L (2017) The efficacy of manual therapy and exercise for treating non-specific neck pain: A systematic review. BMR 30(6):1149–1169

Homem MA, Vieira-Andrade RG, Falci SGM, Ramos-Jorge ML, Marques LS (2014) Effectiveness of orofacial myofunctional therapy in orthodontic patients: a systematic review. Dental Press J Orthod 19:94–99

Jin X, Du H‑G, Qiao Z‑K, Huang Q, Chen W‑J (2021) The efficiency and safety of manual therapy for cervicogenic cephalic syndrome (CCS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000024939

Kamonseki DH, Christenson P, Rezvanifar SC, Calixtre LB (2021) Effects of manual therapy on fear avoidance, kinesiophobia and pain catastrophizing in individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 51:102311

Kendall JC, Vindigni D, Polus BI, Azari MF, Harman SC (2020) Effects of manual therapies on stability in people with musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap 28(1):1–10

Kolber MR, Ton J, Thomas B, Kirkwood J, Moe S, Dugré N, Chan K, Lindblad AJ, McCormack J, Garrison S (2021) PEER systematic review of randomized controlled trials: management of chronic low back pain in primary care. Can Fam Physician 67(1):e20–e30

Kovacs FM, Urrútia G, Alarcón JD (2011) Surgery versus conservative treatment for symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Spine 36(20):E1335–E1351

Kovanur-Sampath K, Mani R, Cotter J, Gisselman AS, Tumilty S (2017) Changes in biochemical markers following spinal manipulation—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 29:120–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2017.04.004

Krøll LS, Callesen HE, Carlsen LN, Birkefoss K, Beier D, Christensen HW, Jensen M, Tómasdóttir H, Würtzen H, Høst CV (2021) Manual joint mobilisation techniques, supervised physical activity, psychological treatment, acupuncture and patient education for patients with tension-type headache. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Headache Pain 22(1):1–12

La Touche R, Martínez García S, Serrano García B, Proy Acosta A, Adraos Juárez D, Fernández PJJ, Angulo-Díaz-Parreño S, Cuenca-Martínez F, Paris-Alemany A, Suso-Martí L (2020) Effect of manual therapy and therapeutic exercise applied to the cervical region on pain and pressure pain sensitivity in patients with temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Med 21(10):2373–2384

Lascurain-Aguirrebeña I, Di Newham, Critchley DJ (2016) Mechanism of action of spinal mobilizations: a systematic review. Spine 41(2):159–172

Lavazza C, Galli M, Abenavoli A, Maggiani A (2021) Sham treatment effects in manual therapy trials on back pain patients: a systematic review and pairwise meta-analysis. BMJ Open 11(5):e45106

Locher H, Bernardotto M, Beyer L, Karadjova M, Vinzelberg S (2022) ESSOMM European core curriculum and principles of manual medicine. Man Med 60(1):3–40

Loudon JK, Reiman MP, Sylvain J (2014) The efficacy of manual joint mobilisation/manipulation in treatment of lateral ankle sprains: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 48(5):365–370

Lystad RP, Bell G, Bonnevie-Svendsen M, Carter CV (2011) Manual therapy with and without vestibular rehabilitation for cervicogenic dizziness: a systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap 19(1):1–11

Martins WR, Blasczyk JC, de Oliveira MAF, Gonçalves KFL, Bonini-Rocha AC, Dugailly P‑M, de Oliveira RJ (2016) Efficacy of musculoskeletal manual approach in the treatment of temporomandibular joint disorder: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Man Ther 21:10–17

Masic I, Miokovic M, Muhamedagic B (2008) Evidence based medicine—new approaches and challenges. Acta Inform Med 16(4):219

Maxwell CM, Lauchlan DT, Dall PM (2020) The effects of spinal manipulative therapy on lower limb neurodynamic test outcomes in adults: a systematic review. J Man Manip Ther 28(1):4–14

de Melo LA, de Medeiros AB, Campos M, de Resende C, Barbosa GAS, de Almeida EO (2020) Manual therapy in the treatment of myofascial pain related to temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 34(2):141–148

Miller J, Gross A, D’Sylva J, Burnie SJ, Goldsmith CH, Graham N, Haines T, Brønfort G, Hoving JL (2010) Manual therapy and exercise for neck pain: a systematic review. Man Ther 15(4):334–354

Namnaqani FI, Mashabi AS, Yaseen KM, Alshehri MA (2019) The effectiveness of McKenzie method compared to manual therapy for treating chronic low back pain: a systematic review. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 19(4):492

Navarro-Santana MJ, Gómez-Chiguano GF, Somkereki MD, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Cleland JA, Plaza-Manzano G (2020) Effects of joint mobilisation on clinical manifestations of sympathetic nervous system activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy 107:118–132

Nim CG, Downie A, O’Neill S, Kawchuk GN, Perle SM, Leboeuf-Yde C (2021) The importance of selecting the correct site to apply spinal manipulation when treating spinal pain: myth or reality? A systematic review. Sci Rep 11(1):1–13

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Paige NM, Miake-Lye IM, Booth MS, Beroes JM, Mardian AS, Dougherty P, Branson R, Tang B, Morton SC, Shekelle PG (2017) Association of spinal manipulative therapy with clinical benefit and harm for acute low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 317(14):1451–1460

Patijn J (2019) Reproducibility protocol for diagnostic procedures in manual/musculoskeletal medicine. Man Med 57(6):451–479

Pieters L, Lewis J, Kuppens K, Jochems J, Bruijstens T, Joossens L, Struyf F (2020) An update of systematic reviews examining the effectiveness of conservative physical therapy interventions for subacromial shoulder pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 50(3):131–141

Pollack Y, Shashua A, Kalichman L (2018) Manual therapy for plantar heel pain. Foot 34:11–16

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Pieper D, Tricco AC, Gates M, Gates A, Hartling L (2019) Preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews (PRIOR): a protocol for development of a reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev 8(1):1–9

Rechberger V, Biberschick M, Porthun J (2019) Effectiveness of an osteopathic treatment on the autonomic nervous system: a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Med Res 24(1):1–14

Roura S, Álvarez G, Solà I, Cerritelli F (2021) Do manual therapies have a specific autonomic effect? An overview of systematic reviews. Plos One 16(12):e260642

Rubinstein SM, van Middelkoop M, Assendelft WJJ, de Boer MR, van Tulder MW (2011) Spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low-back pain: an update of a Cochrane review. Spine 36(13):E825–E846

Salamh P, Cook C, Reiman MP, Sheets C (2017) Treatment effectiveness and fidelity of manual therapy to the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskelet Care 15(3):238–248

Schroeder J, Kaplan L, Fischer DJ, Skelly AC (2013) The outcomes of manipulation or mobilization therapy compared with physical therapy or exercise for neck pain: a systematic review. Evid Based Spine Care J 4(01):30–41

Schulze NB, Salemi MM, de Alencar GG, Moreira MC, de Siqueira GR (2020) Efficacy of manual therapy on pain, impact of disease, and quality of life in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Pain Phys 23(5):461–476

Slater SL, Ford JJ, Richards MC, Taylor NF, Surkitt LD, Hahne AJ (2012) The effectiveness of sub-group specific manual therapy for low back pain: a systematic review. Man Ther 17(3):201–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2012.01.006

Standaert CJ, Friedly J, Erwin MW, Lee MJ, Rechtine G, Henrikson NB, Norvell DC (2011) Comparative effectiveness of exercise, acupuncture, and spinal manipulation for low back pain. Spine 36:S120–S130

Thornton JS, Caneiro JP, Hartvigsen J, Ardern CL, Vinther A, Wilkie K, Trease L, Ackerman KE, Dane K, McDonnell S‑J (2021) Treating low back pain in athletes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 55(12):656–662

Tramontano M, Consorti G, Morone G, Lunghi C (2021) Vertigo and balance disorders—the role of osteopathic manipulative treatment: a systematic review. Complement Med Res 28(4):368–377

Tsokanos A, Livieratou E, Billis E, Tsekoura M, Tatsios P, Tsepis E, Fousekis K (2021) The efficacy of manual therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Ann Univ Mariae Curie Sklodowska [Med] 57(7):696

Ughreja RA, Venkatesan P, Gopalakrishna DB, Singh YP (2021) Effectiveness of myofascial release on pain, sleep, and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract 45:101477

van der Meer HA, Calixtre LB, Engelbert RHH, Visscher CM, Nijhuis–van der Sanden MWG, Speksnijder CM (2020) Effects of physical therapy for temporomandibular disorders on headache pain intensity: a systematic review. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 50:102277

Webb TR, Rajendran D (2016) Myofascial techniques: What are their effects on joint range of motion and pain?—A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Bodyw Mov Ther 20(3):682–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.02.013

Weis CA, Pohlman K, Draper C, Stuber K, Hawk C (2020) Chiropractic care for adults with pregnancy-related low back, pelvic girdle pain, or combination pain: a systematic review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 43(7):714–731

Weis CA, Pohlman K, Draper C, Da Silva-Oolup S, Stuber K, Hawk C (2020) Chiropractic care of adults with postpartum-related low back, pelvic girdle, or combination pain: a systematic review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 43(7):732–743

Wong CK, Abraham T, Karimi P, Ow-Wing C (2014) Strain counterstrain technique to decrease tender point palpation pain compared to control conditions: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Bodyw Mov Ther 18(2):165–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2013.09.010

Xu Q, Chen B, Wang Y, Wang X, Han D (2017) The effectiveness of manual therapy for relieving pain, stiffness, and dysfunction in knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Pain Physician 20(4):229–243

Young JL, Walker D, Snyder S, Daly K (2014) Thoracic manipulation versus mobilization in patients with mechanical neck pain: a systematic review. J Man Manip Ther 22(3):141–153

Zhu L, Wei X, Wang S (2016) Does cervical spine manipulation reduce pain in people with degenerative cervical radiculopathy? A systematic review of the evidence, and a meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 30(2):145–155

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

L. Beyer, S. Vinzelberg, and D. Loudovici-Krug declare that they have no competing interests.

For this article, no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies mentioned were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

Additional information

Scan QR code & read article online

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beyer, L., Vinzelberg, S. & Loudovici-Krug, D. Evidence (-based medicine) in manual medicine/manual therapy—a summary review. Manuelle Medizin 60, 203–223 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00337-022-00913-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00337-022-00913-y