Abstract

This article presents the results of the wood identification of 3,867 everyday objects dated from the 9th to the 15th century ad, which were excavated from 48 medieval strongholds and early urban centres in Poland. The analyses have shown that medieval craftsmen used the wood of 27 tree and shrub taxa. The timber used the most was Pinus sylvestris (pine), Quercus sp. (oak), Fraxinus excelsior (ash) and Alnus sp. (alder). Pine was used mainly to make vessels out of staves (curved pieces of wood) such as buckets and tubs, and for torches for lighting; oak was used for furniture, barrels, cart axles, spades and club hammers used by carpenters. Ash wood was the main material used for making turned bowls, and alder for making articles which were to be in long-lasting contact with water, such as beaters and scoops. Wood studies agree with historical records about the intensive use of yew wood, which finally caused the decrease of Taxus baccata in woodlands in the 14th and 15th centuries. Also, the wood of shrubs such as Euonymus sp. (spindle) and Sambucus sp. (elder) was quite often used. The choice of wood for the specific needs of a particular craft in medieval Poland was done selectively and it was determined by the particular function of the object being made, but at the same time it was limited by availability from the local woodlands. Regional differentiation in the selection of raw material is best indicated in the case of Abies alba (fir). Chronological analysis of the use of wood shows that the number of items made of timber from deciduous trees in all regions of Poland decreased in the late Middle Ages when compared to the Piast period of the early Middle Ages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In medieval Europe, timber was both one of the most important and readily available raw materials which was used in various commercial fields and absolutely essential for making all kinds of items used in everyday life (Mączak 1981; Sönke 2000; Miśkiewicz 2010). This has been shown by archaeological excavations carried out on sites containing well preserved organic material in, for instance, Novgorod, Russia (Brisbane and Hather 2007), Mikulčice, Czech Republic (Poláček et al. 2000) or in an early medieval cemetery in Oberflacht, Germany (Filzer 1992), where numerous everyday wooden objects were discovered. Similar evidence was also provided by archaeological investigations in Poland, such as at Ostrówek in Opole (Bukowska-Gedigowa and Gediga 1986) or Rynek Warzywny in Szczecin, where objects made of wood and bark formed the second most significant group of finds, after those made of leather (Kowalska and Dworaczyk 2011).

The great diversity of functions and dimensions of everyday wooden objects which have been found in many medieval archaeological sites raises questions about the identification of the timber used. Recognising how various kinds of timber were used in medieval crafts is significant for understanding both the woodworking techniques and the management of woodlands by medieval societies. The selective use of some kinds of wood could result in changes to the taxonomic composition of woodlands.

So far, no detailed botanical analyses of medieval objects of everyday use have been carried out in Poland which have reviewed the results of wood anatomical investigations from either a few sites or whole regions. The available archaeological reports which describe the assemblages of wooden artefacts from Polish sites most often concentrate on the form and function of the objects and the type of woodworking techniques used (Dziekoński and Kóčka 1939; Rulewicz 1958; Wilgocki 1995; Earwood 2002/2003; Słowiński 2004). A few papers about the kinds of timber used for making wooden objects have a local character and are mostly published in Polish (Table 1).

The studies of wooden objects from the Mikulčice site in the Czech Republic (Poláček et al. 2000) or Žemutinė Pilias (Lower Castle) in Vilnius (Pukienė 2008) are examples of botanical analyses of useful wood from central and eastern Europe. The taxonomic composition of medieval wood finds from western Europe has been well studied, for instance, from Charavines, France, Elisenhof and Haithabu, Germany (Müller 2008 and the literature cited) and Oberflacht, Germany (Filzer 1992).

The Middle Ages was the first historical epoch in Poland (Salamon and Waśko 2000) and this was a time of intensive changes connected with, among other things, the transition from tribal societies to the beginnings of a state, the establishment of hundreds of early urban centres and the development of handicrafts. Archaeological sources make it possible to distinguish three chronological phases within the early Middle Ages in Poland which differ from each other by the degree of social development and organization of craft production (Buko 2011). These phases are first the early Slavonic period in the second half of the 5th to the 7th century ad, followed by the tribal groupings culminating with the beginning of the Piast dynasty in the 8th to the first half of the 10th century, and finally the Piast state period from the second half of the 10th to the first half of the 13th century (Fig. 1). It should be stressed that the early medieval settlement of Poland was not uniform. It proceeded most quickly in Wielkopolska (Great Poland) and in the southern part of the uplands of Małopolska (Little Poland) (Kornaś 1972; Makohonienko 2004; Buko 2011), which were the most densely populated areas during the late Middle Ages (Fig. 2a), dated in Poland from halfway through the 13th to the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries (Fig. 1; Miśkiewicz 2010). According to Makohonienko (2004), important changes in the development of the vegetational and cultural landscape of Poland took place during the last 2,000 years, but in many regions the most intensive change of plant cover from woodland to mainly open land through human activity was from ca. 1,000 bp. This process is most evident in Wielkopolska and Małopolska and corresponds very well with the leading role of Ziemia Krakowska, the area around Kraków and central Wielkopolska in the 11th century in the formation of the Polish state by the first Piast dynasty (Makohonienko 2004).

a historical regions of early medieval Poland (after Iwaszczuk 2014) and population density in the 15th century (after Gędek 2015, changed); b geobotanical divisions of Poland. A, Dział Pomorski (Pomerania); B, Dział Brandembursko-Wielkopolski (Brandenburg and Great Poland); C, Dział Wyżyn Południowopolskich (southern Polish uplands); D, Dział Wołyński (Volhynia); E, Dział Mazowiecko-Poleski (Mazovia and Polesie); F, Dział Północny Mazursko-Białoruski (Mazuria and Belarus); G, Dział Sudecki (Sudetes); H, Dział Zachodniokarpacki (west Carpathians); I, Dział Wschodniokarpacki (east Carpathians) (after Matuszkiewicz 2008, changed); the main vegetation zones in Europe are indicated on the map (after Kondracki 2009, changed)

The aims of the present investigations, based on rich source material, were as follows: (1) to discover which trees and shrubs were used in medieval Poland for making everyday objects; (2) to find out whether the choice of wood for those purposes was motivated by the specific properties of the timber; and (3) to study possible regional differences in the use of timber for various crafts.

The present-day vegetation of Poland

Poland is situated in the Holarctic Euro-Siberian area (49°00′–54°50′N, 14°07′–24°08′E), in the group of central European vegetational provinces (Medwecka-Kornaś 1972; Wasylikowa 2004; Richling 2009). An important division separating the physical-geographical parts of western and eastern Europe runs through eastern Poland. Most of the part of Poland that belongs to western Europe shows no geographical zonation of vegetation, whereas zonation is distinctly marked in the flat south-western part of the geological East European Platform lying within Poland’s borders. The influences of oceanic and continental climates meet in Poland (Medwecka-Kornaś 1972; Kondracki 2009; Wołkowycki 2010). The temperatures of the summer months increase from west to east, while those of the winter months decrease and the annual temperature amplitude increases too. This temperature pattern is responsible for the transitional character of the vegetation (Wasylikowa 2004; Kondracki 2009). Several plants reach the limits of their ranges in Poland, including some trees and shrubs, such as Fagus sylvatica (beech), Quercus petraea (sessil oak), Acer pseudoplatanus (sycamore), A. campestre (field maple), Tilia platyphyllos (large-leaved lime), Abies alba (silver fir), Taxus baccata (yew) and Crataegus laevigata (hawthorn) (Medwecka-Kornaś 1972; Wołkowycki 2010).

Most of Poland is situated in a subatlantic deciduous and mixed woodland zone belonging to the subatlantic mountainous, Carpathian and middle European vegetational zones. Besides these, two zones are distinguished in eastern Poland, namely the sub-boreal zone with conifer and mixed conifer woods in north-eastern Poland and the woodland steppe zone, east of the river Wieprz (Medwecka-Kornaś 1972; Matuszkiewicz 2008; Richling 2009). Nine main geobotanical divisions are distinguished, reflecting the basic differentiation of Polish vegetation (Fig. 2b; Matuszkiewicz 2008). In the Polish flora the total number of tree and shrub species is small and only amounts to 40 (Pawłowska 1972; Mączak 1981; Danielewicz 2012a).

Materials and Methods

For this study, a taxonomic database of medieval everyday wooden objects from Poland was created, using two data sources: First, identifications previously published by other authors (Table 1) and second, recent wood identifications done by the author (Table 2).

A large range of wooden articles was used for various aspects of everyday life and work in medieval Poland. The majority of the examined objects represent simple items which are commonly found at the sites of that period. Among them are the remains of coopers’ wares from wooden staved vessels such as staves and the end discs of small buckets (Fig. 3, 4, 9), and small stave-built bowls (Fig. 3, 5). There were also turned vessels and other objects, including bowls (Fig. 3, 6), plates (Fig. 3, 2, 7) and lids (Fig. 3, 10); there were hollowed-out and carved vessels such as scoops (Fig. 3, 1), spoons (Fig. 3, 19, 23) and pegs (Fig. 3, 24, 26), and also various tools (Fig. 3, 25, 27, 31, 32, 34), children’s toys, weapons (Fig. 3, 30), musical instruments (Fig. 3, 33) and parts of footware (Fig. 3, 28). Other items taken into consideration included wicker baskets (Fig. 3, 13), bark containers, floats for fishing nets (Fig. 3, 3) and some small construction elements, for example, fragments of workbenches and wooden structures of various sorts (Fig. 3, 12, 18). Remains included means of transport, furniture (Fig. 3, 14) and objects interpreted as parts of buildings, such as roof remains (roof shingles), wall or floor insulation, and even a latrine seat and cover (Fig. 3, 20, 29). The analysis also included wood identification of small objects of unknown function (Fig. 3, 35) and/or representing woodworking waste.

A total of 3,867 wooden objects were identified after being excavated from 48 sites in Polish strongholds and early urban centres (Fig. 4) and dated to the period from the 9th to the 15th century (ESM 2). In the case of the sites at Szczecin Rynek Warzywny, Wrocław Ostrów Tumski, Płock Grodzka 14/16, Płock Grodzka 6 and Kraków Zakrzówek, the authors of the original publications gave no exact numbers of articles made of particular wood taxa. Therefore, in the present paper the following principle was followed: the mention of a taxon as wood used for making a certain category of objects was counted as one.

Selected objects of everyday use from Polish archaeological sites (for extended descriptions, see ESM 1); 1, scoop, Alnus sp.; 2, plate turned on both sides, Acer sp.; 3, float, pine bark; 4, end disc of a stave-built vessel, Abies alba; 5, stave-built bowl, Pinus sylvestris; 6, turned bowl with an incision for a lid, Fagus sylvatica; 7, bowl turned on one side, Fraxinus excelsior; 8, lid of a vessel/float wooden disc/cart wheel?, Pinus sylvestris; 9, tub stave, Taxus baccata; 10, turned lid, Salix sp.; 11, ball, Pinus sylvestris; 12, sinker, Carpinus betulus; 13, fragment of plaited basket, birch bark; 14, furniture fragment, Fraxinus excelsior; 15, 16, parts of folded altars?, Abies alba; 17, torch, Pinus sylvestris; 18, rocker for making cheese, Quercus sp.; 19, spoon, Taxus baccata; 20, piece of latrine seat cover, Quercus sp.; 21, part of folded altar?, Abies alba; 22, hook, Salix sp.; 23, spoon, Abies alba; 24, peg for making rope, Abies alba; 25, carpenter’s club hammer, Quercus sp.; 26, peg, Viscum album; 27, pricker, Abies alba; 28, shoe patten, Salix sp.; 29, piece of latrine cover (horizontal plank with an opening), Pinus sylvestris L.; 30, arrow shaft?, Pinus sylvestris; 31, needle for tying nets, Euonymus sp.; 32, hoe for fire, Quercus sp.; 33, tubular objects with openings, recorder or pipe?, Sambucus sp.; 34, beater, Alnus sp.; 35, object of unknown function, Quercus sp.; photos by K. Cywa

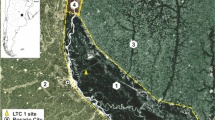

Locations of the find sites and numbers of medieval wood finds. Abbreviations of site names as in Table 2

The objects were arranged into larger groups according to their functions (Fig. 5), in which the tree and shrub taxa most often used for making them can easily be found. In some cases there are apparently similar groups, for example “big stave-built vessels” and “stave-built vessels”. Cooperage (barrels and other articles made with staves) of known sizes was put in the first group, and in the latter the products whose sizes were not specified in the source article.

In order to indicate areas of medieval Poland where a particular kind of wood was especially intensively used, mean values were calculated which give the average number of articles made from each wood taxon at all sites where it occurred. For example, Pinus was found at 30 sites, with an average of 46 articles made of pine per site (ESM 3). The maps of site distribution have been drawn on this basis, showing the sites from which the number of items made of a particular wood taxon was equal to or greater than the average number of items of the taxon from all sites where it occurred (Fig. 6). These calculations make it possible to compare the results of wood identification of the archaeological finds with the modern ranges of trees and shrubs in Poland, and with pollen data providing information about the role they played in medieval woodlands.

Distribution of sites in which the number of wooden objects made from a particular wood was average or above the average from all sites. The northern limit of Abies alba Mill. and the north-eastern limit of Fagus sylvatica L. are shown as dotted lines (after Konopski 2016)

To compare finds of different ages, which came from dozens of sites, each of them was attributed to one of the main chronological periods of the Middle Ages in Poland (ESM 2, Fig. 1). If the dating of these finds crossed the limits of these periods, for example between Period II and Period III (ESM 2, period column), then these were not taken into consideration in the analyses dealing with the chronological aspect (Figs. 7, 8).

Wood analysis

Fossil wood of most of the trees and shrubs growing in Poland can be identified only to genus level by anatomical studies. Picea (spruce) and Larix (larch) are not usually distinguished from each other, in spite of the fact that the anatomical features theoretically useful for more detailed identification have been described (Anagnost et al. 1994). In this article it was necessary to treat it uniformly as one taxon, Picea/Larix, because the data come from various authors, who made identifications to varying degrees of precision.

Wood for microscopic examination was cut directly from the outer surfaces of the objects (Gale and Cutler 2000), corresponding to transversal, longitudinal radial and longitudinal tangential sections. In some cases, when the surface of an object was badly damaged, larger pieces of ca. 0.5 cm3 were collected. The identification was done with the aid of a transmitted light microscope by studying the diagnostic features visible in the three anatomical sections (Lityńska-Zając and Wasylikowa 2005; Gärtner and Schweingruber 2013). For verification, reference material in the collections of the W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Science was used, as well as publications on wood and bark anatomy (Greguss 1945; Schweingruber 1978; Benkova and Schweingruber 2004; Schweingruber et al. 2011).

Results

The identification of medieval wooden objects revealed the occurrence of 27 tree and shrub taxa (Table 3), and also Viburnum sp. (viburnum, wayfaring tree), although only half of them were commonly used and were important as timber for woodworking crafts.

The analyses show that P. sylvestris (pine) wood was the most frequently used, for 36% of artefacts (Fig. 9a). Picea/Larix, Fraxinus, Quercus, Taxus, Alnus, Abies, Acer, Betula, Salix, Euonymus, Sambucus and Fagus were slightly less popular. The wood of these 13 taxa was used for over 90% of all analysed remains.

The use of the bark of eight taxa was also confirmed, Abies alba (fir) (0.03% of all remains), Alnus sp. (0.03%), Betula sp. (0.16%), Larix sp. (0.03%), P. sylvestris (1.73%), Quercus sp. (0.03%), Salix sp. (0.08%) and Tilia sp. (0.08%).

The survival of archaeological finds made of organic materials is determined by the preservation conditions of the site (Fejfer 2011). It is assumed that the amount, quality and proportions of materials found in medieval deposits depend on the type of site, type of object and type of sediment (Lityńska-Zając and Wasylikowa 2005; Buko 2011). In the case of early urban centres, the poor state of stratification there is usually the result of centuries of rebuilding which has destroyed earlier buildings (Buko 2011). This is perhaps the main reason for not having published official data from Poland so far, which would indicate how many archaeological sites dating to the Middle Ages are characterized by very well-preserved organic materials. Assuming that sites with well-preserved archaeological wood are likely to exhibit a low degree of wood degradation as well as a large number of surviving wooden objects, it was found that in the case of the analysed sites, most of the items were relatively well preserved. This is shown by the very low percentage of unidentified objects (0.21% of all remains), as well as ones identified only as deciduous (1.7%) or coniferous (1.6%). Among 48 analysed sites, 21 (44%) only had a few wood remains (< 20 artefacts), 15 (31%) were in the range between 28 and 100 items and 12 sites (25%) are in a group of plentiful finds, where more than 100 objects have survived (Tables 1, 2). It should be borne in mind that the size of a settlement, as well as the amount of woodworking there, may also have had an impact on the number of objects found.

Technological aspect

Listing of the objects according to their functions (Fig. 5) indicates that parts of furniture, timber structures including those for building boats and sledges, various wooden structures, maces (wooden clubs used as weapons and also ceremonially), staves, large stave-built vessels, and large tools such as spades and club hammers were made mainly of Quercus, Pinus and more rarely of Fraxinus. Taxus wood (11.4%) was an important material which was used for making big stave-built vessels, but most often for small and medium sized buckets.

Various kinds of walking sticks, rods and poles were mainly made of Quercus (29.4%), Taxus (17.7%), Pinus (9.8%) and Abies (9.8%). Spear shafts and axe handles as well as maces (clubs) were usually made of Fraxinus. Also, for large handles, Quercus (25%) and Alnus (20.8%) were often used. For arrow shafts, only the wood of P. sylvestris was recorded, and the only crossbow bolt was made of Fraxinus. All of the bows were made of Taxus, and the only shield found, at Podzamcze in Szczecin, was made of Alnus wood.

Small tools and their parts including punches, needles and spindles, as well as knife handles, were made of Pinus (16.1%), Quercus (8%), Euonymus (23.7%), Taxus (13%), Sambucus (6.3%) and Juniperus (0.5%). The material used for making small table spoons was the wood of Acer (26.4%), Fraxinus (4.7%), Betula (7.6%), Alnus (8.5%), Salix (3.8%), Taxus (7.6%), Euonymus (7.6%), Sambucus (2.8%), Juniperus (7.6%), Abies (2.8%) and of some trees and shrubs from the Rosaceae (7.6%).

For making turned objects, besides hollowed and carved ones such as scoops, ladles and beaters, Fraxinus, Quercus, Alnus and Acer were selected most often. Nearly 70% of turned bowls and plates as well as 36% of hollow and carved vessels were made of Fraxinus.

The parts of small stave-built bowls were made of Pinus, Picea/Larix and Abies. The hoops of small stave-built bowls were made exclusively from Salix branches, while those of big buckets or tubs with narrower tops and wider bases were of Taxus (30.8%), Fraxinus (23.1%), Corylus (7.7%), Abies (7.7%) or Picea/Larix (7.7%).

Objects of unknown function were made of Alnus (20.5%), Pinus (12.8%), Quercus (10.3%) and Fraxinus (7.7%).

Torches were usually made of Pinus (61.6%), but sometimes of Picea/Larix (36.6%). The musical instruments were mainly recorders and pipes which were most often made from Sambucus. The wood of Pinus, Fraxinus and Quercus was the usual material for pegs, pins and bungs.

Carved objects (Fig. 5, column: art and cult) were usually made of Abies (23.1%), Alnus (23.1%), Taxus (15.4%) and Acer (15.4%). Children’s toys, which were mainly miniatures of other articles and also pieces used in games were made mostly of Pinus (23.3%). The few fragments of ropes and plaited woodwork were made of Salix branches (85.7%) and phloem (14.3%).

Medieval baskets and containers were woven from various materials, such as thin Pinus (mostly) and Quercus twigs, Betula bark and phloem. The floats for fishing nets were usually cut out of Pinus bark (87.9%).

Geographical aspect

The list of wood identifications from individual sites shows that the most important raw materials in northern (particularly north-western) Poland were Pinus, Quercus, Fagus and Fraxinus (Fig. 10). Quercus was a significant component in the majority of the examined sites. The proportions of Pinus were also marked in almost all sites but were rather low in the south of the country, as in Wrocław and Kraków. The use of Taxus is also evident in the whole of Poland, but the highest proportions in wood composition were noted from the island of Wolin. The significance of Picea/Larix distinctly increases from the north to the south, especially for making stave-built bowls etc. In the south, Picea/Larix is the first or second most important component of the wood spectra.

The number of objects made of Pinus was average or above average in 10 sites, and of Quercus in 11, and Fraxinus in several (Fig. 6, ESM 3).

The pattern of intensive use of Abies alba in the past agrees with the modern distribution of fir in Poland. The sites with the greatest number of objects made of Fagus are also only within its modern distribution range.

The distribution map of the use of Carpinus betulus shows that it exceeds the average value in three sites.

The number of objects made of Betula sp. is above average in two sites only, Opole Ostrówek I–IV and Kraków Wawel X, and the numbers of items made of Taxus baccata reach the mean value in four sites which were scattered over the whole of Poland.

Chronological aspect

The chronological aspect of the wood analyses shows that there are no items dating from the early Slavonic period (Figs. 7, 8). Five objects belong to the early tribal period, a scoop, the end of a barrel, two paddles and a stave of a small bucket made of Taxus. There are 1,710 objects from 14 sites of the state period in the early Middle Ages (Period III) and 1,557 objects from 30 sites of the late Middle Ages (Period IV) (Table 3). Among the items representing Period IV, there are ones characterised by a smaller functional diversity than those in Period III, with a predominance of coopers’ wares, turned objects, pegs and tools. No distinct qualitative difference has been observed in the use of raw materials between the early and late Middle Ages, and the range of woods that were used decreases only insignificantly, from 24 taxa in Period III to 21 in the late Middle Ages (Table 3). Instead, the proportions of the individual taxa in the total composition of wood used are distinctly different. In the material from the late Middle Ages, there is less Quercus, Acer, Alnus, Taxus, Corylus, Betula, Sambucus, Ulmus and more Euonymus, while Abies and Picea/Larix increase. It seems, however, that the differences visible in such a general comparison are first of all connected with the slightly different kinds of wooden objects identified from each period, as well as with the locations of the sites and the local taxonomic composition of the finds from a given chronological phase.

The comparison of wood spectra in Periods III and IV could be done separately for individual sites only for four sites: Szczecin-Podzamcze V/VI, Gdańsk 1, Gdańsk 2, Kraków Wawel X and Kruszwica 4 (Fig. 7). In each site there is a strong decrease in the diversity of wood types in the material from the late Middle Ages, when compared to the state period of the early Middle Ages. This change is associated, however, mainly with a considerable disproportion in the number of items belonging to individual chronological phases. In some cases, as at Szczecin-Podzamcze V/VI and Gdańsk 1, the fewer taxa in Period IV are also influenced by the functional composition of the objects from that period, for instance, when they mainly consisted of turned or stave-built wares.

Discussion

The use of different types of wood in medieval Poland, selected aspects

This research has confirmed the use of various timbers in medieval Poland. The most important material was the wood of Pinus sylvestris. It represented a much valued timber which was used for various purposes due to its lightness and ease of working, as well as its useful qualities such as durability and strength. Pine wood, due to its high content of resinous substances, is durable in air and water (Warywoda 1957; Kocięcki et al. 1991; Szczuka and Żurowski 1999; Kokociński 2004). On the other hand, the high proportion of Pinus in the studied material could also be connected with the occurrence of very many small stave-built vessels or hollow ware made from pine (Fig. 9b). It is interesting that among the objects made of bark, those made of P. sylvestris were the most numerous, 81% of all identifications of bark.

An insignificant occurrence of Tilia (13 objects) and Carpinus (14 objects) among useful medieval wood seems striking, because both taxa are common in the Polish lowlands and foothills (Danielewicz 2012a). These days, Tilia wood is a very popular material which is used in Poland in wood turning, wood carving, sculpture and the production of fancy goods. It is soft, easy to work and cut, and shows a low tendency to warp or crack (Serwa 1986; Surmiński 1991; Samojlik 2005). Carpinus, on the other hand, has a heavy and hard wood which is resistant to abrasion (Serwa 1986; Surmiński 1993), thus making it an excellent timber for applications needing strength. One might also wonder whether the low natural durability of Tilia and Carpinus wood might not be the cause of their poor representation among the medieval archaeological finds. However, Fagus has similar physical properties to Carpinus, and is equally susceptible to damp (Surmiński 1990), yet it was found much more often (43 objects). In an old Polish botanical work from the time of the enlightenment (Kluk 1805), Carpinus was renowned as firewood and its charcoal was considered second only to Fagus. Perhaps Carpinus was used mainly for such purposes in the Middle Ages. A similar suggestion was put forward by Makohonienko (2000) in his analysis of the medieval history of woodland communities in the surroundings of Gniezno. Pollen investigations have shown that a massive expansion of Carpinus in central Wielkopolska took place before the early medieval settlement expansion, and its later decrease was evidently connected with the pressure from human occupation (Makohonienko 2000). Meanwhile, wooden objects made of Carpinus discovered at the site of Ostrów Lednicki, Wielkopolska, amounted to less than 3% of the wood used there, perhaps due to use of its wood for fuel.

In the case of Tilia, the decrease of its pollen values to below 0.5% was recorded in the whole country at the time of the Polish state formation (Kupryjanowicz et al. 2004; Wacnik et al. 2013). It is possible, however, that Tilia was mainly used for its bast fibres, for the oldest Tilia names in several languages are similar to the names of phloem or bast made of Tilia (Boratyńska and Dolatowski 1991). In a way, this conclusion is confirmed by the historical and ethnographic data from the neighbourhood of the Puszcza Białowieska (Białowieża ancient woodland), where the production of bast fibre from the bark was considered an inalienable right of the inhabitants of the surrounding villages. Some information is known from ad 1821 whereby a forest manager stated that this procedure caused more damage to the trees than obtaining wood from them (Samojlik 2005).

The relationship between the kind of wood used and object type and function

Large objects

Relatively large objects, which for their intended uses should be considerably strong and durable, such as architectural elements, pieces of furniture, structures of unknown uses and large tools, were made mainly of Quercus, Pinus and more rarely of Fraxinus. These timbers are characterised by considerable density, weight and hardness in the case of Quercus and Fraxinus, or durability and ease of being split, such as Pinus, Quercus and Fraxinus (Krzysik 1957; Surmiński 1995). Also, big timbers can be obtained for making large objects. The advantage of Quercus as a timber for making staved containers is the presence of tyloses within the vessels which lessen the permeability of its wood. Due to this property, oaken barrels are water- and airtight, which is particularly significant for the storage of various types of foods (Świderski 1966). Taxus wood was important for making big stave-built vessels, but was most often used for small and medium size buckets (Figs. 3, 9). Very hard Taxus wood (Amann 2009) could be an attractive timber for making household goods. Using Taxus wood for containers used mainly for transporting and storing food may seem surprising. The majority of papers on T. baccata have emphasized its toxic properties. In general, it has been claimed that all parts of the Taxus tree are poisonous except the arils enveloping the seeds (Wilson et al. 2001; Falencka-Jabłońska 2004; Berny et al. 2010; Kite et al. 2013). The poisonous properties of Taxus were already known in antiquity. “Celts committed ritual suicide by drinking extracts from yew foliage and used the sap to poison the tips of their arrows during the Gallic Wars” (Wilson et al. 2001). According to Julius Caesar, the king of the Eburones tribe which was conquered by the Romans also poisoned himself with yew “juice” (Wilson et al. 2001). Clearly, not only the leaves had a bad reputation then, as “wine was served in a jar made of yew wood to get rid of an inconvenient person” (Falencka-Jabłońska 2004). Information on the unsuitability of Taxus for drinking vessels can also be found in a medieval and renaissance textbook on agriculture (Crescenzi 1571). A mixture of alkaloids is responsible for the poisonous characteristics of Taxus, taxines which were first found in the leaf-needles of this tree (Theodoridis and Verpoorte 1996). Taxine B is considered the most cardiotoxic (Grobosch et al. 2012; Arens et al. 2016). Because of the wide use of Taxus wood for making pails and buckets in medieval Poland it is noteworthy that the few studies on the toxin content in Taxus wood do not indicate the presence of this taxine in branch heartwood (Kite et al. 2013) nor in the twigs (Ray 2017). Simultaneously, the presence of other types of taxines of unknown toxicity in Taxus wood has been revealed (Kite et al. 2013).

Weapons

The shield from Podzamcze in Szczecin was made of Alnus. The lightness of this wood together with its resistance to splitting and cracking could have been an advantage of using this timber.

Among a few objects that could be interpreted as remains of arrow shafts (Fig. 3, 30), or perhaps rather as semi-finished products, because no traces of a binder or twist fastening flight feathers were found (S. Słowiński, pers. comm.), only the wood of P. sylvestris was identified, just as in the material from Novgorod (Brisbane and Hather 2007). In this case, the lightness of the material together with its considerable hardness would have been of great significance (Jankowski 2008).

Bows found in Poland were made of Taxus, which is consistent with historical records about the use of yew wood (Marcin z Urzędowa 1595). Taxus wood is remarkably elastic and therefore does not crack or warp while drying (Kłosiewicz and Kłosiewicz 2011). Sapwood has a high tensile strength while heartwood withstands compression, qualities which are particularly relevant for longbows (Gale and Cutler 2000). Taxus wood was not only used by local craftsmen but was also exported. The first information about Poland’s trade in yew wood with the Netherlands comes from 1287 (Czartoryski 1975). According to historical sources, Taxus almost completely disappeared from Polish woods and for that reason became the basis of a royal law of 1423 that prohibited its felling (Czartoryski 1975; Cedro 2004; Pawelec 2010).

Small tools

In medieval deposits, various types of small tools have often been found, such as punches, needles and spindles, as well as handles for knives, borers or other small tools, which in accordance with their function should have great strength. Interestingly, such objects were very often made from the wood of small trees or shrubs, including Euonymus, Taxus and Sambucus, as well as Pinus and Quercus. Such wood has an exceptional hardness and density, exceeding that of Quercus. The frequent use of Taxus wood for making handles could be connected with its outstanding suitability for polishing, rendering it perfect for creating very smooth surfaces on objects. Euonymus, with its heavy and slightly flexible wood was used, among other things, as the main material for making spindles, hence its name, “spindle tree”. This means that the choice of wood for making these particular objects was not made by chance (Cywa 2016). Such uses of Euonymus sp. are consistent with the records of the use of this shrub in other parts of medieval Europe, such as at Dolny Zamek in Vilnius, Lithuania (Pukienė 2008), and at the Danish site of Svendborg (Müller 2008 and references). Euonymus was also used for making fork-shaped shuttles and needles used for tying and repairing fishing nets (Fig. 3, 31). Added to the group of relatively small articles which require hardness and strength are also a hammer handle from Wawel hill (Fig. 5, column: big tools) and a comb discovered in the Rynek (market square) in Wrocław (Fig. 5, column: outfit and hygiene). These objects were made of Cornus, which is very heavy and as hard as Euonymus (Krzysik 1957). The fact that the hard wood of shrubs was not used for making larger objects may be because their branches were too small.

Spoons

The material used for making small table spoons was fairly varied. Acer wood was the most common one, then Fraxinus, Betula, Alnus and Salix, which are all easy to work (Krzysik 1957; Serwa 1986), as well as the very hard woods of Taxus, Euonymus, Sambucus, Juniperus, Abies and of some rosaceous trees and shrubs. Evidently, both the ease and speed of working (more often) as well as the hardness and durability of the products were taken into consideration. It cannot be overlooked that the aesthetic values of Taxus, Euonymus and Juniperus woods, such as smoothness and colour, as well as the easy shaping of woodcarving details, favoured their use. This suggestion is confirmed by the wood identifications of well worked and decorated spoons that were mostly made of Taxus. It is worth mentioning that according to old Polish customs, spoons were generally carried under a belt (Gołębiowski 1830). In a sense, they were treated like personal equipment with an exceptional and individual character, which was constantly exposed to damage.

Turned, carved and drilled kitchen utensils

The choice of raw material for making turned objects, in addition to carved and planed ones, depended not only on attributes connected with their function but also on the kind of woodwork involved. Fraxinus, Alnus and Acer were selected most often. The wood of these trees is fairly homogenous, straight grained and durable, but soft enough to be easily worked. These are also fairly large trees, which makes it possible to make relatively large objects from single pieces of wood. The narrow growth rings of Fraxinus timber make it usually considered to be soft enough to work easily, both cutting it into planks and turning (Krzysik 1957; Surmiński 1995). In the book about farming by P. Crescenzi (1571), there is a statement that Fraxinus was a wood used first of all for making various domestic dishes. One- and two-sided turned dishes were made of it, but the latter were also made of Acer timber. Also, as a result of turning wood to make bowls, etc. on a lathe, there are waste cores from the middle of the turned wood pieces. In this group of “objects” only Fraxinus and Acer were identified.

The use of Alnus as the main wood for making scoops and most of the beaters, used for washing cloth among other things, could be because of its exceptional durability when in permanent contact with water. It must be added that Alnus wood becomes mineralized when soaked in water, which improves its strength, hardness and durability. This process is due to the precipitation of water soluble calcium and magnesium bicarbonates, which upon converting into inert salts, deposit on the cell walls of Alnus wood. This phenomenon is fastest in shallow standing water which warms up easily (Surmiński 1980). In the old Polish economic and technical herbarium of Gerald-Wyżycki (1845) there is a guide on how to prepare Alnus wood for a turner and a carpenter, according to which the wood should be put in water for 3 years in order to reach its proper hardness and durability.

Small stave-built bowls and other coopers’ goods

Small stave-built bowls (Fig. 3, 5), which most probably were used mainly for eating from (Polak 1996; Wysocka 2001), were only made of softwoods, namely Pinus, Picea/Larix and Abies, which are not as strong as, for instance, Taxus. These woods have great (Larix), medium (Pinus) or little (Picea, Abies) hardness but are both light and easy to split, particularly Picea and Pinus (Krzysik 1957), allowing craftsmen to make thin staves from them. Interestingly, the end discs of these bowl types were made mostly from Pinus, while their staves were Picea/Larix. This may be explained by the rules in coopers’ craft handbooks, whereby the use of pine wood for making containers used for food storage was limited due to the strong smell. Picea can be used for food storage purposes because its wood has a small number of resin canals (Świderski 1966). The use of Picea/Larix for making the side staves of containers, which have a much larger surface area than the end disc, could have reduced the influence of resin on food. No information was found about the influence of Larix wood on food.

Wooden hoops, used for fastening the sides of stave-built vessels, were made by hoopers. Wood analyses have shown that in order to make hoops for small stave-built bowls, thin Salix (willow) branches were split longitudinally (Fig. 11, 1a, b).

Selected everyday objects from Polish archaeological sites; 1a, stave of a small stave-built bowl, Pinus sylvestris with remains of hoop made of Salix sp. (Szczecin-Podzamcze V/VI, inv. no. 1288, collections of the National Museum in Szczecin); 1b, transversal section of the hoop, half of the branch; 2, the structure of a peg (after Molski 1968), which joined planks of a clinker-built boat (Szczecin-Podzamcze V/VI, inv. no. 7661); 3a, wooden end disc of a basket, Pinus sylvestris (Szczecin-Podzamcze V/VI, inv. no. 8549, collections of the National Museum in Szczecin); 3b, sharpened end of a vertical piece of plaited woodwork, Pinus sylvestris (photos by K. Cywa)

Ambiguous function

The group of objects of undefined function includes wooden balls (Fig. 3, 11) and discs with a hole in the centre (Fig. 3, 8), which are interpreted by archaeologists as fishing equipment, such as floats and net sinkers, dish lids or items used for games and toys such as balls or rattle-boxes or wheels from baby carriages (Dziekoński and Kóčka 1939; Ostrowska 1962; Świętek 1999). In the case of these object types, wood analysis does not offer an unequivocal answer as to their use. Some balls and rings were made from heavy, hard and strong kinds of wood, such as Quercus and Fraxinus (toys?), while the others were from much lighter and more water-resistant timbers, such as Alnus and Pinus (floats?). However, the fact that these objects were most often made out of alder points to a close connection with fishing.

Torches

Torches were made of Pinus and Picea/Larix (Fig. 3, 17). The main reason for this choice was that this wood can catch fire quickly and burn with a large flame, because of the considerable quantity of resinous substances in the wood (Surmiński 1970, 1986). Highly resinous wood absorbs less water and can catch fire more easily, which could have been important, especially in rainy weather.

Musical instruments

Among the items interpreted as musical instruments, the most common are tubular objects with openings (Fig. 3, 33), which according to archaeologists could be fragments of pipes or recorders. All objects of that kind, as well as tubular objects without openings, were made of thin Sambucus branches, which have an easily removable, exceptionally broad and spongy pith. It is interesting that the name Sambucus is a Latinized form of the Greek word, “sambuke”, meaning “pipe”. According to the ethnographic information about ancient Poland, in order to repel evil powers from huts and farmyards, village musicians played on pipes made of Sambucus (Kłosiewicz and Kłosiewicz 2011). The parts of medieval sounding boards and bodies of stringed instrument were made of various wood types, Tilia, Pinus, and Quercus. On the other hand, the mouthpiecees of musical instruments were cut from thin Salix twigs or from Picea/Larix and Betula.

Pegs, pins and wedges

With respect to wood types used, the most varied group was composed of pegs, pins and wedges, which were made from all available wood types, but largely from Pinus, Quercus, Fraxinus and Abies. Thin and sharpened pegs of unknown uses were made mainly of pine. Much larger items, often used in architectural elements, as well as pin-type pegs which joined, for instance, two parts of barrel lids composed of many segments, were produced from Fraxinus and less often Quercus. Dowels joining the staves of plank-built boats had a particularly interesting and complex structure. Their outer part was made of relatively soft pine wood while in the inner was a wedge of hard oak wood (Fig. 11, 2). The use of two types of wood is explained in the following way: the wedging of pegs in the planks had to be done very tightly, which could smash pine pegs (Molski 1968).

Footware

A wooden patten found at the Toruń Bankowa 14/16 site represents an interesting object (Fig. 3, 28). It is a sort of wedge-heeled sole which was put on shoes for protection against street dirt (R. Uziembło, personal communication). The specimen examined was made of Salix sp.

Fun and entertainment

On Polish archaeological sites toy boats made of pine bark have been found very often, which could easily float, just like real boats, due to the properties of the material used. Bark is a very simple material to work, and thanks to that, an attractive toy could be made of it quickly and without much work.

Baskets

Some medieval baskets were wholly woven from Pinus and Quercus twigs or Betula bark (Fig. 3, 13), while others had wooden end discs of pine with holes around the circumference into which the ends of the basket-work were inserted (Fig. 11,3a, b).

Floats

Most floats for fishing nets (Fig. 3, 3) were cut out of pine bark. Sometimes, thick Salix or Betula bark from the lower part of the trunk was used for this purpose.

Insulation

Betula bark was also used as a water repellant insulation. A complete chest lined with birch bark fragments for keeping cereals was found at the site of Bródno Stare (Ruszkowska et al. 2011).

Regional differences in the timbers used for making wooden articles

The pattern of wood use according to the intended function and purpose of the particular wooden articles, as mentioned above, is generally similar in all regions of Poland. However, there are some differences in composition of the wood used in certain areas, connected with the local availability of particular trees and shrubs (Fig. 10). When considering the geobotanical variation of Polish vegetation and the limitations of the wood identification methods, one can see that regional differences in the selection of wood are best expressed in the use of Abies, which was an important resource, but only in southern Poland. The use of Abies coincides with the distribution of fir in Poland, which is mainly in mountainous areas. The northern limit of the range of A. alba is in central Poland (Danielewicz 2012a). Abies wood was found at Radom 2, Wrocław Ostrów Tumski, Wrocław Rynek, Wrocław Szewska and Oławska, Opole Ostrówek I–IV and in most sites in Kraków. According to the wood identifications, Abies, in addition to Picea/Larix, was the most frequently used kind of wood there, while in sites in Wielkopolska and Pomorze, northern Poland (Pomerania) it occurred sporadically or was totally absent. A few examples of the use of Abies in Pomorze Zachodnie (western Pomerania) are a spoon from Szczecin Rynek Warzywny and three objects of unknown function from Szczecin-Podzamcze V/IV and V/VI, which are conventionally described by archaeologists as icons or portable altars (Fig. 3, 15, 16, 21). Images of saints could have been placed on oval depressions in these objects (S. Słowiński, personal communication). In their general scheme these artefacts, a thin plate with a depression, are like objects discovered in the medieval cultural layers in Novgorod, which are described as mirror cases and they were also made of Pinus sp. (Brisbane and Hather 2007). Altars and mirrors were luxury goods and therefore they could have come from long distance trade, which developed widely in Poland as late as the 13th century (Małowist 1938; Samsonowicz 1973). The dating of the Szczecin icons/altars, from the second quarter of the 13th and third quarter of the 13th century to the end of the 14th century, fits this time period. Consequently, these objects could be evidence of the early medieval importing of Abies timber from southern areas.

In the case of P. sylvestris, Quercus sp., Fraxinus excelsior, A. alba, Fagus sylvatica and Carpinus betulus, a distinct correlation was observed between the distribution of sites where their wood was most intensively used and the modern distributions of these trees in Poland (Fig. 6). The number of objects made of pine or oak wood reached the mean value in several of the analysed sites, thus confirming that these timbers were widely used and easily accessible there (Ralska-Jasiewiczowa et al. 2004). A similar tendency can be seen on the map showing the use of Fraxinus. It is worth noting that among wood deposits which contain a large number of objects, only those from Kraków are not marked on this map, which may be explained by the fact that turned objects, which are the main products of Fraxinus wood working, are very rare in these deposits.

The evidence of intensive use of A. alba and F. sylvatica wood agrees with the modern distributions of fir and beech in Poland (Fig. 6). It should be mentioned that north-eastern parts of Poland, which were at least partially beyond the range of Fagus during medieval times (Wacnik et al. 2016), also provided the smallest number of archaeological sites and the fewest wood finds.

It is interesting that the map showing the use of Carpinus betulus wood, a species very poorly represented among the archaeological finds, shows that it exceeds the mean values in three sites: Ostrów Tumski in Wrocław, Ostrów Lednicki and Toruń Bankowa 14–16 (Fig. 6). This coincides with pollen investigations which indicate that there were woodlands with much hornbeam in those areas before the spread of medieval settlement (Makohonienko 2000).

The number of objects made of Betula sp. exceeds the mean value in two sites only. Birch is a very common tree in Poland (Danielewicz 2012a). It includes pioneer trees that spread easily on land previously cleared by human activities (Wacnik et al. 2014; Bronisz et al. 2016; Jagodziński et al. 2017), which makes access to the timber easy. Taking into consideration the fact that Betula wood is easy to work and hardly warps (Surmiński 1979), it was probably used by medieval craftsmen. Low representation of this wood among the everyday medieval objects may thus be connected with its poor natural durability (Surmiński 1979).

The number of items made of Taxus baccata wood reached the mean value only in four sites. It is worth observing that the mean number of objects of yew wood is strikingly high compared to some larger trees, such as Fagus or Abies (ESM 3), which combined with its scarcity in woodland communities (Iszkuło et al. 2016) additionally emphasises the intensive use of Taxus in the Middle Ages.

The information based on analysis of the relationship between the taxonomic composition of medieval wood deposits and locations of the archaeological sites indicates that in most cases the wood spectra reflect the local availability of trees and shrubs in the surroundings. These conclusions agree with the opinions of archaeologists and historians about the great importance of local production, exchange and trade in medieval Poland (Samsonowicz 1973).

Relationship between the age of the material and taxonomic diversity of the wood

Wooden objects found in medieval archaeological sites show a typological similarity, so that articles have universal forms over extended periods of time, and undergo no distinct changes (Barnycz-Gupieniec 1959; Wysocka 1999; Łosiński et al. 2003; Müller 2008). Studying medieval artefacts can lead to the question whether there were any changes in the use of timbers due to changes in the woodlands around the sites from human activities, or to developments in woodworking crafts.

In order to compare archaeological finds from chronological periods II, III and IV, all of the objects were grouped according to the historical regions of medieval Poland (Figs. 2a, 8). This arrangement shows that in the late Middle Ages, in all regions of Poland, the number of objects made of deciduous tree and shrub wood decreased, except for Quercus and Fraxinus, whereas the use of coniferous wood remained at a similar level in the early and late Middle Ages. The composition of coniferous taxa used in the individual regions, however, changed distinctly. During the Piast period in the early Middle Ages, pine wood was most often used in Małopolska (Little Poland) and Śłąsk (Silesia, southern Poland), as in other parts of the country. By the late Middle Ages the use of this wood in southern regions distinctly decreased, while that of Picea/Larix and Abies increased. In other regions of Poland, the proportion of P. sylvestris wood in the wood spectra did not change. Historical sources indicate that in the late Middle Ages, pine timber from Małopolska was probably exported and that this trade developed on a large scale in Poland as late as the 14th century (Danielewicz 2012b). Pine wood with narrow growth rings grown in southern Poland, as well as from Russia and Lithuania, was highly appreciated for boat building (Gerlach 2011), although the best pine timber, known as mast pine, came from Puszcza Knyszyńska, northeast Poland (Kłosiewicz and Kłosiewicz 2011).

Among the coniferous taxa, only the wood of Taxus baccata was poorly represented in the late Middle Ages in the whole of Poland. This agrees with historical and pollen data according to which a decline of Taxus took place as early as the early Middle Ages (Czartoryski 1975; Cedro 2004; Pawelec 2010; Iszkuło et al. 2016).

The use of wood in medieval Poland in relation to the other countries in eastern and central Europe

The results of the identifications of medieval archaeological wood from Polish archaeological sites show several similarities with those obtained on the past uses of wood in other parts of eastern and central Europe. In Novgorod, Russia (Brisbane and Hather 2007), about 710 km from the eastern border of Poland, the wood of Pinus, Quercus and Fraxinus was also used very often. Taxus, Alnus and Picea were present too. Fraxinus wood, just as in Poland, was an important timber there for making turned vessels, while Pinus and Taxus were used for making stave-built containers. Alnus was used for making carved and hollowed vessels, and a spade for removing snow, suggesting that this wood was used in wet conditions, just as in Polish sites. On the Žemutinė Pilie (Lower Castle) site in Vilnius, Lithuania, Acer was frequently used for making scoops and spoons (Pukienė 2008). In Poland this wood was also one of the main ones used for making spoons and it was also used for plates and bowls turned on both sides. In the Žemutinė Pilie site at Vilnius, pine wood was mainly used for making parts of architectural structures, furniture and other things as well as large tools like spades. In contrast to Poland, Lithuanian craftsmen seldom used Quercus and Fraxinus, yet frequently used Betula. Tilia was found there more often than in Poland. In the Mikulčice site, Czech Republic, Quercus, Acer and Fraxinus were the main timbers used (Poláček et al. 2000). As in Poland, oak was used there mainly for making building structures and cooperage (barrels etc.), and Acer and Fraxinus for scoops and axe handles. Interestingly, in two cases axe handles were also made from Tilia. The staves of buckets were made of Taxus and yew was also used for these at the Devínska Nová site, Slovak Republic (Eisner 1952; Gluza 1977). The comparison of the results of wood analyses from Poland and southern Germany shows certain similarities, first of all in woodworking and object functions. For instance, in the medieval cemetery in Oberflacht (Filzer 1992), Acer and Fraxinus predominated among the turned objects, while Quercus was mainly used in architectural pieces, mostly planks of burial chambers. In the material from Elisenhof, the main timber used was Quercus, while Taxus and Sambucus appeared very often, which are two small trees or shrubs with strong wood (Müller 2008 and references).

Conclusions

Identifications of 3,867 wooden artefacts recovered from 48 archaeological sites in Poland make it possible to conclude that in the Middle Ages the choice of timber for the needs of handicrafts was deliberate and was motivated by the technological and working properties of particular kinds of wood. In each case, however, the possibility of obtaining the preferred timber was limited by its availability in the local woodlands.

Wood analyses have shown a great diversity of wood material used for making everyday objects in medieval Poland, but only some of the identified taxa were used on a large scale. Over 90% of the examined items were made of Pinus, Picea/Larix, Fraxinus, Quercus, Taxus, Alnus, Abies, Acer, Betula, Salix, Euonymus, Sambucus and Fagus.

The most frequently used wood was P. sylvestris, a widespread tree in the Polish flora, which was readily available. In addition to lightness, other useful properties such as its strength and ease of splitting, as well as its durability and ease of working, would have favoured it as a fairly universal timber. Staved vessels, both big buckets and small bowls, and also torches, were mainly made from pine. The articles which required durability and strength were made of Quercus, such as furniture, barrels, architectural elements, parts of wheels and axles, spades and carpenters’ club hammers. Picea/Larix was used for small stave-built bowls and for torches. Plates and bowls were turned from Fraxinus, and Alnus was used for making items to be exposed to prolonged contact with water, including net rings/floats, beaters, ladles and scoops.

Contrary to the common belief in the toxicity of Taxus baccata, it has been found that yew wood was frequently used for making big stave-built vessels. As yew wood was also used at various sites in Poland, as well as in other regions of central and eastern Europe as at Novgorod and Mikulčice, the issue of the toxicity of the wood of T. baccata to humans and animals requires further toxicological studies which take account of the content of various alkaloids in the wood.

It is particularly interesting that besides large trees, which nowadays play a leading role in the modern forestry industry, the wood of shrubs was fairly frequently used in the Middle Ages, such as Euonymus and Sambucus, which are not presently used either on an industrial scale or in small crafts. Euonymus sp. was the main wood for making spindles and Sambucus sp. for whistles or recorders.

The analysis of wood use, according to the locations of the sites, indicates a regional differentiation connected with the availability of particular trees and shrubs in the neighbourhoods of the sites, which were in strongholds and early urban centres. This can most clearly be seen in the use of Abies, which was used mainly in the parts of southern Poland which lie within the range of natural fir distribution. A few objects made of Abies discovered further away, in Szczecin, could be examples of trade in wooden objects or sporadic imports from distant places.

The studies have shown that the number of items made of the wood of deciduous trees and shrubs decreased in the late Middle Ages compared to the Piast period of the early Middle Ages in all of the historical regions of medieval Poland. Wood analyses also confirm historical information about the intensive use of Taxus in the early Middle Ages, which brought about a significant decrease of yew trees in medieval woodlands.

Similarities between Poland and other countries in central and eastern Europe are shown by the particular use of some wood taxa such as Acer for making spoons as in Lower Castle, Vilnius, Taxus for stave-built vessels, as in Novgorod, Mikulčice and Devínska Nová, Euonymus for making spindles, as in Žemutinė Pilie, Vilnius and in Svendborg, and Fraxinus as the material for making turned vessels as in Oberflacht.

References

Amann G (2009) Drzewa i krzewy, Kieszonkowy atlas, Seria flora i fauna lasów [Trees and shrubs, pocket atlas, a series on the flora and fauna of woodlands, in Polish]. Multico Oficyna Wydawnicza, Warszawa

Anagnost SA, Meyer RW, De Zeeuw C (1994) Confirmation and significance of Bartholin’s method for the identification of the wood of Picea and Larix. IAWA J 15:171–184

Arens AM, Anaebere TC, Horng H, Olson K (2016) Fatal Taxus baccata ingestion with perimortem serum taxine B quantification. Clin Toxicol 54:878–880

Barnycz-Gupieniec R (1959) Naczynia drewniane z Gdańska z X–XIII wieku [10th–13th century wooden vessels from Gdańsk, in Polish, with French summary]. Acta Archaeologica Universitatis Lodziensis 8:1–109

Barnycz-Gupieniec R (1961) Tokarstwo i bednarstwo z XIII–XIV wieku w osadzie miejskiej w Gdańsku. [The turnery and coopery in the town of Gdańsk in the 13th–15th centuries, in Polish, with English summary]. Materiały Zachodnio-Pomorskie 7:391–434

Benkova VE, Schweingruber FH (2004) Anatomy of Russian woods. Haupt, Wien

Berny P, Caloni F, Croubels S, Sachana M, Vandenbroucke V, Davanzo F, Guitart R (2010) Animal poisoning in Europe. Part 2: companion animals. Vet J 183:255–259

Bobik I (2012) Zabytki drewniane z późnośredniowiecznej latryny [Wooden artefacts from a late medieval latrine, in Polish, with German summary]. Archeologia Stargardu 1:185–195

Boratyńska K, Dolatowski J (1991) Systematyka i geograficzne rozmieszczenie [Systematics and geographical distribution, in Polish,with English summary]. In: Białobok S (ed) Lipy Tilia cordata Mill Tilia platyphyllos Scop. Nasze Drzewa Leśne XV. Polska Akademia Nauk, Instytut Dendrologii, Arkadia, Poznań, pp 21–55

Brisbane M, Hather J (eds) (2007) Wood use in medieval Novgorod. (The archaeology of medieval Novgorod 2. Oxbow Books, Oxford

Bronisz K, Strub M, Cieszewski C, Bijak S, Bronisz A, Tomusiak R, Wojtan R, Zasada M (2016) Empirical equations for estimating aboveground biomass of Betula pendula growing on former farmland in central Poland. Silva Fenn. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf1559

Buko A (2011) Archeologia Polski wczesnośredniowiecznej. Odkrycia—hipotezy—interpretacje. [The archaeology of early medieval Poland. Discoveries—hypotheses—interpretations, in Polish with English summary]. Wydawnictwo TRIO, Warszawa

Bukowska-Gedigowa J, Gediga B (1986) Wczesnośredniowieczny gród na Ostrówku w Opolu. [Early medieval stronghold in Ostrówek in Opole, in Polish, with German summary]. (Polskie Badania Archeologiczne 25) Zakład Narodowy im Ossolińskich, Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk, Instytutu Historii Kultury Materialnej, Wrocław

Cedro A (2004) Wpływ warunków klimatycznych na kształtowanie się przyrostów radialnych cisa pospolitego (Taxus baccata L) w rezerwacie Cisy staropolskie w Wierzchlesie [Influence of climatic conditions on the radial increments of yew (Taxus baccata L.) from Cisy Staropolskie Reserve in Wierzchlas, in Polish, with English summary]. Prace Geograficzne IGiPZ PAN 200:47–57

Cnotliwy E, Leciejewicz L, Łosiński W (eds) (1983) Szczecin we wczesnym średniowieczu, Wzgórze Zamkowe. [Szczecin in the Early Middle Ages, Castle Hill (Wzgórze Zamkowe), in Polish]. (Polskie Badania Archeologiczne 23) Zakład Narodowy im Ossolińskich, Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk, Wrocław

Crescenzi P (1571) Piotra Crescentyna, O pomnożeniu i rozkrzewieniu wszelakich Pożytkow Ksiąg Dwoienaście: Ludziom Stanu każdego/którzyby się gospodarstwem bawili/wielce potrzebne i użyteczne [Twelve volumes on the multiplication and spreading of any yield: Greatly needed by and useful for people of all classes who try their hand at farming, in Polish]. Wydawnictwo Stanisława Szarfenberga, Kraków

Cywa K (2016) Znaczenie użytkowe drewna Euonymus sp. w średniowiecznej Polsce [Uses of spindle tree Euonymus sp. wood in medieval Poland (in Polish, English summary)]. Fragmenta Floristica et Geobotanica Polonica 23:321–347

Cywa K (2017) Analysis of wood and bark remains from the site in Czermno [Analiza pozostałości drewna i kory ze stanowiska w Czermnie]. In: Florek M, Wołoszyn M (eds) The early medieval settlement complex at Czermno in the light of results from past research (up to 2010). Material evidence 1. Wczesnośredniowieczny zespół osadniczy w Czermnie w świetle wyników badań dawnych (do 2010). Podstawy źródłowe, vol 1]. U źródeł Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej/Frühzeit Ostmitteleuropas, Tom 2, część 1/Band 2, Teil 1, Kraków-Leipzig-Rzeszów-Warszawa, pp 499–509 (in press)

Czartoryski A (1975) Z przeszłości cisa [Yew in the past, in Polish]. In: Białobok S (ed) Cis pospolity Taxus baccata L. Nasze Drzewa Leśne III. Polska Akademia Nauk, Instytut Dendrologii, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warszawa-Poznań, pp 134–140

Danielewicz W (2012a) Drzewa leśne Polski [Polish woodland trees, in Polish]. In: Matuszkiewicz W, Sikorski P, Szwed W, Wierzba M (eds) Zbiorowiska roślinne Polski, Lasy i zarośla, Ilustrowany przewodnik [Polish plant communities, woodland and thickets, illustrated guide, in Polish]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa, pp 21–61

Danielewicz W (2012b) Zagrożenia i ochrona zbiorowisk leśnych [Threats to and protection of woodland communities, in Polish]. In: Matuszkiewicz W, Sikorski P, Szwed W, Wierzba M (eds) Zbiorowiska roślinne Polski, Lasy i zarośla, Ilustrowany przewodnik [Polish plant communities, woodland and thickets, illustrated guide, in Polish]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa, pp 74–86

Dzieduszycki W (1976) Wykorzystywanie surowca drzewnego we wczesnośredniowiecznej i średniowiecznej Kruszwicy [The use of timber in early medieval and medieval Kruszwica, in Polish, with German summary]. Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej 24:35–54

Dziekoński T, Kóčka W (1939) Przedmioty drewniane z grodu gnieźnieńskiego [Wooden artefacts from Gniezno stronghold, in Polish]. In: Kostrzewski J (ed) Gniezno w zaraniu dziejów (od VIII–XII wieku) w świetle wykopalisk [Gniezno at the dawn of history (from 8th to 12th centuries) in the light of excavations, in Polish]. (Biblioteka Prehistoryczna 4) Polskie Towarzystwo Prehistoryczne, Poznań, pp 136–145

Earwood C (2002/2003) Wooden artefacts from the medieval town of Dawidgródek. Belarus Wiadomości Archeologiczne 56:393–430

Eisner J (1952) Devínska Nová Ves [Devínska Nová Ves, in Czech]. Nakl Slovenskej akadémie vied a umení, Bratislava

Falencka-Jabłońska M (2004) Conservation of common yew (Taxus baccata L.) in Poland. In: Vančura K, Fady B, Koskela J, Mátyás C (eds) Conifers network, Report of the second (20–22 September 2001, Valsaín, Spain) and third (17–19 October 2002, Kostrzyca, Poland) meetings. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, pp 31–34

Fejfer M (2011) Monitorowanie warunków zalegania pozostałości osady kultury łużyckiej w Biskupinie jako przykład ochrony zabytków drewnianych na mokrym stanowisku archeologicznym [Monitoring of depositional conditions of the Lusatian Culture settlement finds in Biskupin as an example of timber monuments protection in a wet archaeological site, in Polish, with English summary]. In: Pelczyk A, Wyrwa AW (eds) Konserwacja drewna zabytkowego miedzy teorią a praktyką. Biblioteka Studiów Lednickich 23. Muzeum Pierwszych Piastów na Lenicy, Dziekanowice-Lednica, 65–77

Filzer P (1992) Die Holzproben von Oberflacht. In: Schick S (ed) Das Gräberfeld der Merowingerzeit bei Oberflacht (Gemeinde Seitingen, Lkr. Tuttlingen). Theiss, Stuttgart, pp 121–127

Gale R, Cutler D (2000) Plants in archaeology: identification manual of vegetative plant materials used in Europe and the Southern Mediterranean to c. 1500. Westbury Publishing and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Otley

Gerald-Wyżycki J (1845) Zielnik ekonomiczno-techniczny, czyli opisanie drzew, krzewów i roślin dziko rosnących w kraju, jako też przyswojonych, z pokazaniem użytku ich w ekonomice, rękodziełach, fabrykach i medycynie domowej, z wyszczególnieniem jadowitych i szkodliwych, oraz mogących służyć ku ozdobie ogrodów i mieszkań wiejskich ułożony dla gospodarzy i gospodyń [An economic and technical herbarium describing the trees, bushes and plants growing wild in the country as well as those assimilated, demonstrating their use in economy, handicraft, factories and home medicine, detailing poisonous and harmful species, and those that can be used as decoration of gardens and rural dwellings; arranged for hosts and hostesses, in Polish], vol 1. Drukiem Józefa Zawadzkiego, Wilno

Gerlach K (2011) Drewno szkutnicze do końca epoki żagla [Boatbuilding timber until the culmination of the ‘Era of Sail’, in Polish]. Warszawska Firma Wydawnicza, Warszawa

Gluza I (1977) Szczątki drewna z wczesnośredniowiecznego cmentarzyska w Krakowie na Zakrzówku. [Wood remains from an early medieval cemetery in Zakrzówek, Kracow, in Polish, with French summary]. Materiały Archeologiczne 17:201–203

Gluza I (2009) Zabytki drewniane z badań archeologicznych prowadzonych na Małym Rynku w Krakowie w 2007 roku—analiza paleobotaniczna. [Palaeobotanical analysis of wooden artefacts from archeological research conducted in Mały Rynek in Krakow in 2007, Polish, with English summary]. Materiały Archeologiczne 37:103–105

Gorczyński T, Molski B, Pogorzelska I (1969) Struktura drewna z wykopaliska “Rynek Warzywny” w Szczecinie [Wood structure from the archaeological excavation “Vegetable Market” in Szczecin in Poland, in Polish, with English summary]. Rocznik Dendrologiczny 23:5–38

Gostwicka J (1965) Dawne meble Polskie [Old Polish furniture, in Polish, with French summary]. Wydawnictwo Arkady, Warszawa

Gołębiowski Ł (1830) Domy i dwory, przy tym opisanie apteczki, kuchni, stołów, uczt, biesiad, trunków i pijatyki; łóżek, pościeli, ogrodów, powozów i koni; błaznów, karłów, wszelkich zwyczajów dworskich i różnych obyczajowych szczegółów [Houses and mansions, including the description of the first-aid kit, kitchen, tables, feasts and banquets, liquors and carousals; beds, bedding, gardens, carriages and horses; clowns, dwarves, all types of courtly customs and various societal curiosities, in Polish]. Druk N. Glücksberga, Warszawa

Grabska M (1979) Przedmioty drewniane [Wooden objects, in Polish]. In: Cofta-Broniewska A (ed) Zaplecze gospodarcze Konwentu OO. Franciszkanów w Inowrocławiu od połowy 14 w [The base of supplies of the monastery of the Franciscan order in Inowrocław, in Polish]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu im Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu, Poznań, pp 117–144

Greguss P (1945) Bestimmung der mitteleuropäischen Laubhölzer und Sträucher auf xylotomischer Grundlage. Ungarisches Naturwissenschaftliches Museum, Hungarian Museum of Natural History, Budapest

Grobosch T, Schwarze B, Stoecklein D, Binscheck T (2012) Fatal poisoning with Taxus baccata. Quantification of paclitaxel (taxol A), 10-Deacetyltaxol, baccatin III, 10-deacetylbaccatin III, cephalomannine (taxol B), and 3,5-dimethoxyphenol in body fluids by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol 36:36–43

Grupa M (2000) Sprzęt i wyposażenie gospodarstwa domowego [Household inventory and equipment, in Polish, with English summary]. In: Kurnatowska Z (ed) Wczesnośredniowieczne mosty przy Ostrowie Lednickim [Early medieval bridges at Ostrów Lednicki, in Polish], Mosty traktatu gnieźnieńskiego. Biblioteka Studiów Lednickich 5, vol 1. Muzeum Pierwszych Piastów na Lednicy, Lednica-Toruń, pp 139–162

Gärtner H, Schweingruber FH (2013) Microscopic preparation techniques for plant stem analysis. Kessel, Remagen-Oberwinter

Gędek M (2015) Atlas historii Polski [Atlas of Polish history, in Polish]. Bellona, Warszawa

Głosek M, Kajzer L (1977) Łuk średniowieczny znaleziony w Brzegu [Medieval bow discovered in Brzeg, in Polish]. Silesia Antiqua 19:241–250

Głosek M, Uciechowska-Gawron A (2009/2010) Wczesnośredniowieczna tarcza z podgrodzia w Szczecinie. [An early medieval shield from the borough in Szczecin (Polish, with English summary)] Materiały. Zachodniopomorskie Nowa Seria 6/7:269–284

Iszkuło G, Pers-Kamczyc E, Nalepka D, Rabska M, Walas Ł, Dering M (2016) Postglacial migration dynamics helps to explain current scattered distribution of Taxus baccata. Dendrobiology 76:81–89

Iwaszczuk U (2014) Animal husbandry on the Polish territory in the Early Middle Ages. Quat Int 346:69–101

Jagielska I (2009/2010) Badania i konserwacja drewnianej tarczy ze szczecińskiego Podzamcza [The study and conservation of a wooden shield from Podzamcze in Szczecin, in Polish]. (Materiały Zachodniopomorskie Nowa Seria, z. 1. Archeologia 6/7:285–297

Jagodziński AM, Zasada M, Bronisz K, Bronisz A, Bijak S (2017) Biomass conversion and expansion factors for a chronosequence of young naturally regenerated silver birch (Betula pendula Roth) stands growing on post-agricultural sites. For Ecol Manage 384:208–220

Jankowski J (2008) Kusza i łuk, rzemiosło średniowieczne i współczesne [Crossbow and bow, medieval and contemporary crafts, in Polish]. Wydawnictwo Replika, Zakrzewo

Kite GC, Rowe ER, Veitch NC, Turner JE, Dauncey EA (2013) Generic detection of basic taxoids in wood of European Yew (Taxus baccata) by liquid chromatography–ion trap mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B 915–916:21–27

Kluk JK (1805) Dykcjonarz roslinny, w którym podług układu Linneusza są opisane rosliny nie tylko kraiowe, dzikie, pożyteczne albo szkodliwe: na roli, w ogrodach, oranżeryach utrzymywane: ale oraz y cudzoziemskie, ktoreby w kraiu pożyteczne bydz mogły: albo z ktorych mamy lekarstwa, korzenie, farby, etc albo ktore jakową nadzwyczayność w sobie mają: ich zdatności lekarskie, ekonomiczne, dla ludzi, koni, bydła, owiec, pszczoł, etc utrzymywanie, etc Z poprzedzającym wykładem słów Botanicznych i kilkorakim na końcu Reiestrem [A lexicon of plants where plants are described using the Linnaean taxonomy, not only those in the country, wild, beneficial or harmful, growing in the field the garden or keptorangeries, but also foreign ones, which could be put to good usethe country or can be used to make medicine, roots, paint, etc, or which contasome special properties: medical, economic, for people, horses, cattle, sheep, bees, etc, preceded by a list of botanical terms and with a register added at the end,Polish, vol 1. Drukarnia Xięży Piarów, Warszawa

Kocięcki S, Zdanowski A, Kolk A, Rzadkowski S, Sobczak R (eds) (1991) Mała encyklopedia leśna A little encyclopaedia of the forest, in Polish]. PWN, Warszawa

Kokociński W (2004) Drewno pomiary właściwości fizycznych i mechanicznych [Wood—measurements of physical and mechanical properties, in Polish]. Prodruk, Poznań

Kondracki J (2009) Geografia regionalna Polski [Regional geography of Poland, in Polish]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa

Konopski M (2016) Środowisko przyrodnicze, Zasięgi wybranych gatunków drzew [Natural environment, the ranges of selected trees, in Polish]. In: Bański J (ed) Atlas obszarów wiejskich w Polsce [Atlas of rural areas in Poland, in Polish], IGiPZ PAN, Warszawa. https://www.igipzpanpl/atlas-obszarow-wiejskich-rozdzial1.html. Accessed 10 Oct 2016

Kornaś (1972) Wpływ człowieka i jego gospodarki na szatę roślinną Polski. Flora synantropijna [The influence of man and his economy on Polish vegetation. Synanthropic flora, in Polish]. In: Szafer W, Zarzycki K (eds) Szata Roślinna Polski [The flora of Poland, in Polish], vol 1. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warszawa, pp 95–127

Kowalska AB, Dworaczyk M (2011) Szczecin wczesnośredniowieczny, Nadodrzańskie centrum [Early medieval Szczecin, centre by the river Oder in Polish, with English summary]. (Seria Origines Polonorum 5) Fundacja na rzecz Nauki Polskiej. Instytut Archeologii i Etnologii PAN, Wydawnictwo TRIO, Warszawa

Krzysik F (1957) Nauka o drewnie [Wood science, in Polish]. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Rolnicze i Leśne, Warszawa

Kupryjanowicz M, Filbrandt-Czaja A, Noryśkiewicz AM, Noryśkiewicz B, Nalepka D (2004) Tilia L—Lime. In: Ralska-Jasiewiczowa M, Latałowa M, Wasylikowa K, Tobolski K, Madeyska E, Wright HE Jr, Turner C (eds) Late Glacial and Holocene history of vegetation in Poland based on isopollen maps. W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, Kraków, pp 217–224

Kłosiewicz S, Kłosiewicz O (2011) Przyroda w polskiej tradycji. Ocalić od zapomnienia [Nature in Polish tradition. Saving from oblivion, in Polish]. Sport i Turystyka, Muza SA

Łaszkiewicz T, Michalak A (2007) Broń i oporządzenie jeździeckie z badań i nadzorów archeologicznych na terenie Międzyrzecza [Weaponry and horse-riding equipment from archaeological exavations and observations on the site of the medieval town of Międzyrzecz, in Polish, with English summary]. Acta Militaria Mediaevalia 3:99–176

Lityńska-Zając M, Wasylikowa K (2005) Przewodnik do badań archeobotanicznych [Guide to archaeobotanical research, in Polish]. Sorus, Poznań

Łosiński W, Dworaczyk M, Kowalska AB, Rulewicz M (2003) Szczecin we wczesnym średniowieczu. Wschodnia część suburbium [Szczecin in the early Middle Ages, Eastern suburbs, in Polish]. Instytut Archeologii i Etnologii Polskiej Akademii Nauk, Szczecin

Makohonienko M (2000) Przyrodnicza historia Gniezna [Natural history of Gniezno, in Polish]. Homini, Bydgoszcz-Poznań

Makohonienko M (2004) Late Holocene period of increasing human impact. In: Ralska-Jasiewiczowa M, Latałowa M, Wasylikowa K, Tobolski K, Madeyska E, Wright HE Jr, Turner C (eds) Late Glacial and Holocene history of vegetation in Poland based on isopollen maps. W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, Kraków, pp 411–413

Marcin z Urzędowa (1595) Herbarz Polski to jest o przyrodzeniu ziół i drzew rozmaitych i inszych rzeczy do lekarstw należących księgi dwoje [Polish herbarium on the nature of various herbs and trees, and other items used as medicine, compiled in two volumes, in Polish]. Drukarnia Łazarzowa, Kraków

Matuszkiewicz JM (2008) Zespoły leśne Polski [Polish forest communities, in Polish]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa

Małowist M (1938) Polish-Flemish trade in the Middle Ages. Baltic Scandinavian Countries 4:1–9

Medwecka-Kornaś A (1972) Czynniki naturalne, wpływające na rozmieszczenie geograficzne roślin w Polsce [Natural factors influencing the geographic distribution of plants in Poland, in Polish]. In: Szafer W, Zarzycki K (eds) Szata Roślinna Polski, tom I [The flora of Poland, in Polish]. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warszawa, pp 35–94

Miśkiewicz M (2010) Życie codzienne mieszkańców ziem polskich we wczesnym średniowieczu [Day-to-day life of inhabitants of Polish lands in the early Middle Ages, in Polish]. Uniwersytet Kardynała Stefana Wyszyńskiego w Warszawie, Państwowe Muzeum Archeologiczne w Warszawie, Wydawnictwo TRIO, Warszawa

Molski B (1968) Gatunki drewna używane w średniowiecznym Szczecinie do wyrobu przedmiotów codziennego użytku [Wood species used in medieval Szczecin for the manufacture of objects of everyday use, in Polish, with English summary]. Archeologia Polski 13:491–502

Müller U (2008) Drechseln und Böttchern - Holz verarbeitende Handwerke. In: Melzer W (ed) Archäologie und mittelalterliches Handwerk—Eine Standortbestimmung. (Soester Beiträge zur Archäologie 9) Westfälische. Verlagsbuchhandlung Mocker & Jahn, Soest, pp 169–199

Mączak A (ed) (1981) Encyklopedia historii gospodarczej Polski do 1945 roku, A-N [Encyclopaedia of Poland’s economic history until 1945, A-N, in Polish], vol 1. Wiedza Powszechna, Warszawa