Abstract

Objectives

In this proof of concept study, a deep learning–based method for automatic analysis of digital mammograms (DM) as a tool to aid in assessment of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) treatment response in breast cancer (BC) was examined.

Methods

Baseline DM from 453 patients receiving NACT between 2005 and 2019 were included in the study cohort. A deep learning system, using the aforementioned baseline DM, was developed to predict pathological complete response (pCR) in the surgical specimen after completion of NACT. Two image patches, one extracted around the detected tumour and the other from the corresponding position in the reference image, were fed into a classification network. For training and validation, 1485 images obtained from 400 patients were used, and the model was ultimately applied to a test set consisting of 53 patients.

Results

A total of 95 patients (21%) achieved pCR. The median patient age was 52.5 years (interquartile range 43.7–62.1), and 255 (56%) were premenopausal. The artificial intelligence (AI) model predicted the pCR as represented by the area under the curve of 0.71 (95% confidence interval 0.53–0.90; p = 0.035). The sensitivity was 46% at a fixed specificity of 90%.

Conclusions

Our study describes an AI platform using baseline DM to predict BC patients’ responses to NACT. The initial AI performance indicated the potential to aid in clinical decision-making. In order to continue exploring the clinical utility of AI in predicting responses to NACT for BC, further research, including refining the methodology and a larger sample size, is warranted.

Key Points

• We aimed to answer the following question: Prior to initiation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, can artificial intelligence (AI) applied to digital mammograms (DM) predict breast tumour response?

• DMs contain information that AI can make use of for predicting pathological complete (pCR) response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer.

• By developing an AI system designed to focus on relevant parts of the DM, fully automatic pCR prediction can be done well enough to potentially aid in clinical decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) for breast cancer (BC) is increasingly used for patients with early-stage disease who are eligible for chemotherapy [1]. Advantages include assessment of treatment response with the option to continuously alter the systemic regime and provide an individualised prognosis post-NACT. From a surgical perspective, NACT enables less invasive surgery, both in terms of causing tumour shrinkage that would permit breast-conserving surgery and lowering the rates of axillary dissections due to recent treatment changes with the use of post-NACT sentinel lymph node biopsies [2, 3]. In addition, the recently introduced concept of salvage adjuvant chemotherapy for patients who do not achieve pathological complete response (pCR) further utilises the NACT setting [4,5,6].

In a clinical routine, assessment of disease stage (T- and N-stage) for BC patients undergoing NACT is based on imaging of the breast and the axilla. Common imaging includes digital mammograms (DM) and axillary ultrasound (US), whereas breast US, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) are less often used [7]. Imaging can predict a high degree of disease progression but has discouraging results when predicting pCR, a surrogate for survival [8, 9]. In clinical practice and research, different approaches can be used to monitor tumour responses during NACT: (1) clinical exam (most commonly used), (2) dynamic changes in tumour size as measured by imaging, (3) sequential biopsy of the tumour to evaluate change in biomarkers (often proliferation marker Ki67) and (4) molecular biomarkers in blood samples drawn over the time course of treatment [10, 11].

Previously, we investigated the impact of breast density on treatment response prediction as a means to extract additional data from the clinical DM but did not obtain any conclusive results by using this method [12, 13]. Going beyond a mere value of breast density, evidence that certain breast parenchymal patterns and tumour appearances, which could potentially have an impact on treatment response, are associated with the breast tissue milieu have been demonstrated [14, 15].

In this proof of concept study [16], we introduce a deep learning–based method for automatic DM analysis as a tool to aid in treatment response assessment. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have shown outstanding performance in image recognition tasks as this process automatically learns feature representation in a general manner from pixels in medical images according to corresponding class annotations [17]. Our hypothesis is that treatment response is affected by breast parenchymal patterns and tumour appearances as reflected by different grey-level pixel presentations or the features of images that can be deciphered using a CNN. The aim of this work was to develop a DM-based CNN model that will provide the discriminative power of pCR. The clinical question at hand can be asked: ‘Prior to initiation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, can we predict tumour responses utilising artificial intelligence (AI) in DM?’.

Materials and methods

Cohort

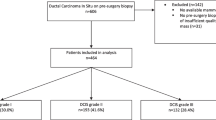

The cohort consisted of female BC patients undergoing NACT (chemotherapy, and in cases of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 [HER2] positivity, combined with HER2 blockade) for BC in Sweden from 2005 to 2019. A total of 493 patients were eligible for the AI model. The reasons for exclusion (50 patients) are pictured in Fig. 1. The study cohort (453 patients) consisted of a retrospective (N = 258, treatment period 2005–2016) and a prospective cohort (N = 195, treatment period 2014–2019) as previously described [18]. The inclusion criteria for both cohorts were female patients treated with NACT undergoing the intended breast surgery. Medical charts and study-specific patient questionnaires (filled out upon diagnosis) were reviewed and data on patients’ characteristics were retrieved.

In total, 90% (N = 408) of the patients received a chemotherapy regimen consisting of a combination of epirubicin and cyclophosphamide (EC)/fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide (FEC) and docetaxel/paclitaxel. Additionally, 8% (N = 38) of the patients received taxane-only NACT regimen and a total of 1% (N = 4) of the patients received FEC/EC only. The remainder 1% (N = 3) received various other regimens. For the patients with HER2 positive tumours (N = 134), N = 89 (66%) received trastuzumab, N = 43 (32%) received trastuzumab and pertuzumab, and the remaining two (1%) received no HER2 targeted treatment.

Information about tumour pathology from the surgical specimen following NACT was derived from clinical-pathological reports. In accordance with national guidelines, tumour hormone receptor positivity was defined according to staining positive in > 10% of the tumour cells with immunohistochemistry (IHC), and HER2 status was defined as either 3 + with IHC and/or amplified with fluorescence in situ hybridisation [11]. The proliferation marker Ki67 (reported as a percentage from 0 to 100%), was considered highly proliferative when Ki67 > 20%, and otherwise low proliferative [11]. The following definition for pCR was used: the absence of any residual invasive cancer in the resected breast after surgery as well as all sampled regional lymph nodes following completion of NACT [19].

All women with any baseline DMs were included in this study. From the eligible patients (N = 493), drawn randomly while maintaining the cohort pCR ratio, a test set of 60 (12%) patients were set aside for final assessment. The development and execution of the AI model led to the exclusion of 40 (8%) patients; 23 (5%) were excluded because only one breast had been imaged and 17 (3%) were excluded due to technical errors of which 15 (3%) were formatted incorrectly and two (0.4%) had corrupt files (Fig. 1). Four-hundred (88%) patients were used for model training and validation in an 80/20 ratio, and 53 (12%) for final assessment (of the original N = 60 in the reserved test set) (Table 1). This study was designed in accordance with the Strengthening of the Reporting of Observational Studies (STROBE) guidelines [20].

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Lund, Sweden (committee’s reference number: 2014/13, 2014/521 and 2016/521).

Imaging

DM were retrieved from local picture archiving system (Sectra AB) and/or prospectively stored on a local server. The 2514 processed DM (training N = 1796 DM, validation N = 422 DM and test set N = 296 DM) selected for analysis originated from the following vendors: (1) GE Healthcare (31%), (2) Philips Healthcare (16%) and (3) Siemens Healthineers (52%). All patients had sets of either six or four images with an average of 5.5 images acquired from both breasts and all available views (cranio-caudal and medio-lateral oblique for all patients and additional lateral-medial views in the set of six images). The important image parameters are collected from the standardised meta-information, i.e. Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) tags. When this was not standardised, we encountered technical issues as in N = 15 cases. All operations are invariant to any remaining differences.

Neural networks

The deep learning system used to predict pCR in DM consists of two main steps: (1) a network for detection tumours is first applied to the DM and (2) image patches are extracted around the detected tumour in addition to the same position in the reference image (contralateral cancer-free breast). The two image patches are fed into a classification network (Fig. 2) that predicted pCR. By extracting smaller image patches of interest, the classification network is forced to make predictions based on what we hypothesised to be relevant information instead of overfitting the information to irrelevant input.

Classification model architecture. Image patches from the detected tumour and corresponding position in the reference image were processed in two parallel pathways. The feature output from the two pathways was concatenated and processed by a series of fully connected layers and a final soft-max layer. The numbers shown in the image denotes the size of the feature dimension

For detection, a detection transformer (DETR) model was selected [21]. The model uses the whole DM as input and predicts the location and size of tumours in the form of bounding boxes. Apart from changing the number of output classes to one tumour, we followed the same training and inference procedures as described in the original paper [21]. For training, we used the publicly available Curated Breast Imaging Subset of DDSM (CBIS-DDSM) consisting of scanned film mammography studies paired with bounding boxes of tumours [22]. In total, we used 1485 images during training and validation of the detection network. Before being input to the model, histogram equalisation was performed on the images. This step was crucial for allowing the detection model to perform well on the images in the cohort presented in this paper. The equalisation was done to increase the contrast in the images as well as decrease differences between images from different vendors. This is done by using the normalised histogram of the original image intensities to remap the pixel intensities [23]. The resulting image will have a uniform distribution of image intensities. Equalisation was done on the range of intensities available in the original image, excluding zero.

The classification network consists of two parallel pathways in which the first one processes the image patch extracted from the detected tumour, and the second one processes the patch extracted from the reference image. The two pathways have the same base structures as ResNet18 [24] with a strided convolution at the end, which reduces the spatial size of the feature maps to 1 × 1. The features from the two pathways are then concatenated and processed through a series of fully connected and dropout layers to finally output classification scores for pCR, and non-pCR, a visualisation of the network structure can be seen in Fig. 2.

The classification network processed the DM in the original resolution of 0.085 and 0.085 mm per pixel for Siemens and Philips systems and 0.1 and 0.1 mm per pixel for GE systems. The size of the image patches input was 224 × 224 pixels. For the images in which multiple tumours were detected, a random one was chosen during training, whereas for images without detected tumours, a random area was selected in the foreground of the imaging areas within the breast contour. The training was done using cross-entropy loss and stochastic gradient descent with a learning rate 1e−3, momentum 0.9, weight decay 1e−4 and dropout rate of 0.5 for all dropout layers. Training was done for 300 epochs, and the weights from the epoch with lowest validation loss were used. During inference, the classification network was applied to all detected tumours averaging the output. For the final estimated patient pCR probability, the output for all available views was averaged.

Statistical analyses

We summarised cohort baseline characteristics for the whole cohort as absolute values and as percentual shares that were split by pCR status with pCR binary outcome. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves were constructed, and a two-sided Mann–Whitney U test was used for statistical significance testing. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

For both descriptive and analytic statistics, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26 (IBM Corp.) was used.

Results

Descriptive results

The patient and tumour characteristics of the 453 patients included in this study are presented in total and according to pCR in Table 1. A total of 95 patients (21%) achieved pCR. The median age was 52.5 years (interquartile range [IQR] 43.7–62.1), and 255 (56%) patients were premenopausal. The median tumour size at baseline was 30.0 mm (IQR 22.0–40.0); the patients in the pCR group presented somewhat smaller tumours (26.5 mm, IQR 20.0–34.5) in comparison to the non-pCR group (31.5 mm, IQR 22.5–40.0). The majority of the patients had highly proliferative tumours (N = 361, 80%) and presented with nodal metastases at diagnosis (N = 307, 68%). In terms of the St. Gallen subtype, patients with luminal A–like tumours were in the minority (as is to be expected given the criteria for receiving NACT), and none of these patients achieved pCR. Correspondingly, descriptive statistics for the randomly drawn test set (N = 53) is presented in Table 2; the test set shows similar patients and tumour characteristics of the cohort as a whole.

AI

The AI output probability pCR scores for the test set are shown in Fig. 3, and the associated ROC curve is illustrated in Fig. 4. The AI model showed a performance of predicting pCR as represented by the area under the curve [AUC] of 0.71 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.53–0.90; p = 0.036). The sensitivity at a fixed false-positive rate of 0.10 (90% specificity) was 0.46. Please note that false-positive here refers to AI predicting pCR where in fact the patient did not accomplish pCR.

Discussion

Prediction of treatment response, upfront or as early as possible, is important in order to offer BC patients individualised treatment. Currently, evaluation of responses to NACT includes anatomical imaging, functional imaging (metabolic evaluation through PET/CT), and possibly biomarker evaluation [10, 25]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first one investigating the use of AI on baseline DM to predict treatment responses. In this report, we present results of a deep learning–based method on baseline DM and its capability to subsequently identify patients who achieved pCR, resulting in an AUC of 0.71.

AI and treatment response evaluation

Tahmassebi et al. conducted a study using machine learning based on both pre- and during-NACT MRI (N = 38) with residual cancer burden as an outcome measure (with class zero being defined as pCR), which yielded an AUC of 0.86 [26]. A study by Qu et al. presented results of a deep learning–based method applied to MRI (N/training = 244, N/validation = 58) using pCR as an outcome measure and showed an AUC of 0.55 using pre-NACT data in comparison to an AUC of 0.97 when using post-NACT data or the combination of both pre- and post-NACT MRI [27]. Sutton et al. applied machine learning to pre- and post-NACT MRI (N/training = 222, N/validation = 56) and showed an AUC between 0.78 and 0.83. In the latter model, the molecular subtype was added to radiomics [28]. From the I-SPY TRIAL breast MRI database, an implemented CNN algorithm on MRI (N = 131) showed an AUC of 0.72 [29]. Similarly, CNN used in a pre-NACT MRI study by Ha et al. (N = 141) showed an AUC as high as 0.98 [30]. Cain et al. built multivariate machine learning models (logistic regression and a support vector machine) based on pre-NACT MRI (N/training = 144, N/ validation = 144), which resulted in an AUC of 0.71 [31]. Nevertheless, our results suggest that our AI model on DM is in the range of those based on pre-NACT MRI. The most obvious advantages of DM are easy accessibility worldwide in contrast to the expensive and more complicated imaging methods of MRI and PET/CT.

Predictive factors for NACT response

It is well known that different BC subtypes with their heterogeneous biology respond differently to NACT [32]. Generally, the most aggressive BC subtypes are associated with higher pCR rates [32]. On the other hand, the relevance of pCR as an outcome measure is less certain for luminal BC, which is often considered a less aggressive subtype [32, 33]. In addition to BC subtype and immunohistochemical parameters, immunological markers (such as tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes), tumour-genetic profiles (which are commonly used in the adjuvant setting), and immune-associated signatures hold predictive information at baseline [34,35,36]. However, the tumour and its relation to the surrounding tissue must be taken into account. The local microenvironment and the systemic host characteristics also influence tumour response, and these properties are not routinely included in medical decision-making and treatment algorithms [11, 37]. Increased mammographic density, MRI background parenchymal enhancement, higher age and higher body mass index have been suggested to be associated with lower rates of pCR [13, 38,39,40]. In addition, multiple studies have investigated dynamic predictive factors, for example, predicting pCR status by considering a change in various biomarkers, such as tumour immune microenvironments [41], measurements of cell loss [42] and circulating tumour cells [43]. Many tumour response studies using structural and functional imaging studies are published using both conventional and state-of-the-art imaging, including mammography, tomosynthesis, ultrasound, MRI, PET and shear wave elastography [44,45,46,47]. Evaluating AI in breast tomosynthesis would be an interesting line of research for future studies. In order to fine-tune predictive information, many nomograms have been developed that consider multiple parameters aiming to optimise precision in estimation of response to NACT [48]. Recently, the concept has been further developed by evaluating the predictive performances of machine learning using clinical and pathological data [49].

Implications of identifying pCR/non-pCR

In order to individualise NACT treatment, more biomarkers, including imaging biomarkers, are needed. Tools to early identify responders from non-responders could aid clinical decision-making, motivate patients to continue treatment, and enable the concept of response-guided treatment as introduced in the GeparTrio study [50]. Since response-guided treatment is currently lacking convincing evidence of its benefits, the common strategy is to complete NACT unless evident progression or intolerable side effects occur [11, 37]. Early identification of patients who are not likely to achieve pCR after subsequently administrated NACT has the potential to improve tailored treatment and escalate/de-escalate treatment accordingly. On the other hand, in the post-NACT setting, the potential clinical gain is mostly a surgical matter; if imaging in combination with minimally invasive procedures could lead to a considerably high degree of correctly identified pCR, further invasive surgery for these patients may not be needed.

Digital mammograms: AI versus breast radiologists

To evaluate the performance of our AI model in relation to the performance of radiologists, seven experienced radiologists jointly reached an AUC of 0.71 in correctly discriminating between pCR and non-pCR (unpublished data from the NeoDense trial [12]) for the post-NACT time point by evaluating DM. The baseline NeoDense study-specific protocol was not designed for the radiologists to estimate subsequent pCR status after completion of NACT; therefore, a more direct comparison between performances at the pre-NACT time point was not possible. Also, comparison with MRI is not possible since this modality is not currently used for this purpose at the study sites.

Strengths and limitations

We present the results of a relatively large BC patient cohort who received NACT according to clinical routine. Conventional imaging was used according to the local routine at the time being; thus, MRI, as used by many other researchers, was not available. While hindering direct comparison, the use of DM makes our study unique since, to the best of our knowledge, no literature is available concerning AI application to baseline DM to predict treatment response during NACT for BC patients. Before AI training, a test set of patients were set aside for final assessment, enhancing validity of our results. The concerns with a binary output as pCR must be briefly acknowledged. Many post-NACT pathological assessment scores also reflect partial responses, possibly providing a more nuanced prognosis. The importance of these results is most evident when considering salvage adjuvant chemotherapy for which residual cancer burden score 1 (“near-pCR”) shows as good an outcome as patients who achieved a pCR [51]. Nevertheless, convincingly, pCR is still the most widely accepted endpoint in NACT studies.

A limitation of our study is the heterogeneous cohort in terms of both BC subtype and time period for NACT treatment. Unfortunately, the cohort was not large enough to perform subgroup analyses according to BC subtype since AI modelling demands a large number of images. Here, we shortly address possible concerns of the long recording period (2005–2019) and possible changes in NACT treatment during this time period. For both cohorts, the standard NACT contained series of FEC or EC followed by series of taxanes (docetaxel or paclitaxel) and, in the case of HER2-positive tumour, combined with HER2 blockade (trastuzumab/pertuzumab). Thus, the NACT regimen was consistent during the recording time and we therefore believe this to be of minor impact.

Future aspects

Next, we will train AI using dynamic DM from three time points during NACT and further explore explainable AI by identifying the areas on the mammograms that AI find most informative to generate “heat maps.” In addition, the concept of AI-guided response evaluation during NACT can be applied to other medical images for other organs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study describes an AI platform using baseline DM to predict the response to NACT in BC patients. The initial AI performance presents the potential to aid in the clinical decision-making. In order to continue exploring the clinical utility of AI in predicting response to NACT for BC, further research including refined methodology and a larger sample size is warranted. Overall, our proof-of-concept study of the response evaluation highlights an important area of AI research in BC. In addition, our study might prompt future studies in NACT-treated cancer patients in general and, therefore, has implications beyond BC.

Change history

22 February 2022

In this article the following funding information was added: Open access funding provided by Lund University.

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CNN:

-

Convolutional neural network

- DM:

-

Digital mammograms

- EC:

-

Epirubicin and cyclophosphamide

- FEC:

-

Fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NACT:

-

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- pCR:

-

Pathological complete response

- PET/CT:

-

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristics

- US:

-

Ultrasound

References

Burstein HJ, Curigliano G, Loibl S et al (2019) Estimating the benefits of therapy for early-stage breast cancer: the St. Gallen International Consensus Guidelines for the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2019. Ann Oncol 30:1541–1557. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz235

Mohiuddin JJ, Deal AM, Lund JL et al (2017) Evaluating the effectiveness of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in reducing mastectomy for women with breast cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr 1(1):pkx004. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncics/pkx004

Cardoso F, Kyriakides S, Ohno S et al (2019) Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-updagger. Ann Oncol 30(8):1194–1220. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz173

von Minckwitz G, Huang CS, Mano MS et al (2019) Trastuzumab emtansine for residual invasive HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 380(7):617–628. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1814017

Masuda N, Lee SJ, Ohtani S et al (2017) Adjuvant capecitabine for breast cancer after preoperative chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 376(22):2147–2159. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1612645

Denduluri N, Chavez-MacGregor M et al (2018) Selection of optimal adjuvant chemotherapy and targeted therapy for early breast cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol 36(23):2433–2443. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8604

Expert Panel Breast I, Slanetz PJ, Moy L et al (2017) ACR appropriateness criteria((R)) monitoring response to neoadjuvant systemic therapy for breast cancer. J Am Coll Radiol 149(11S):S462–S475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2017.08.037

Houssami N, Macaskill P, von Minckwitz G, Marinovich ML, Mamounas E (2012) Meta-analysis of the association of breast cancer subtype and pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer 48(18):3342–3354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.05.023

Kong X, Moran MS, Zhang N, Haffty B, Yang Q (2011) Meta-analysis confirms achieving pathological complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy predicts favourable prognosis for breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 47(14):2084–2090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.014

Weber WA (2009) Assessing tumor response to therapy. J Nucl Med 50(Suppl 1):1S-10S. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.108.057174

Bröstcancer -Nationellt vårdprogram (2020). Available via https://kunskapsbanken.cancercentrum.se/globalassets/cancerdiagnoser/brost/vardprogram/nationellt-vardprogram-brostcancer.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2021

Skarping I, Fornvik D, Heide-Jorgensen U et al (2020) Mammographic density changes during neoadjuvant breast cancer treatment: NeoDense, a prospective study in Sweden. Breast 53:33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2020.05.013

Skarping I, Fornvik D, Sartor H, Heide-Jorgensen U, Zackrisson S, Borgquist S (2019) Mammographic density is a potential predictive marker of pathological response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. BMC Cancer 19(1):1272. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6485-4

Huo CW, Chew GL, Britt KL et al (2014) Mammographic density-a review on the current understanding of its association with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 144(3):479–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-2901-2

Sartor H, Zackrisson S, Hegardt C, Larsson C (2021) Association of mammographic features with molecular breast tumor profiles. Cancer Treat Res Commun 28:100387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctarc.2021.100387

Halligan S, Kenis SF, Abeyakoon O, Plumb AAO, Mallett S (2020) How to avoid describing your radiological research study incorrectly. Eur Radiol 30:4648–4655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-020-06720-0

Shen D, Wu G, Suk HI (2017) Deep learning in medical image analysis. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 19:221–248. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071516-044442

Skarping I, Fornvik D, Heide-Jorgensen U et al (2021) Mammographic density as an image-based biomarker of therapy response in neoadjuvant-treated breast cancer patients. Cancer Causes Cont 32:251–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-020-01379-w

Bossuyt V, Provenzano E, Symmans WF et al (2015) Recommendations for standardised pathological characterization of residual disease for neoadjuvant clinical trials of breast cancer by the BIG-NABCG collaboration. Ann Oncol 26(7):1280–1291. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv161

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al (2008) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61(14):344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

Carion N. MF, Synnaeve G., Usunier N., Kirillov A., Zagoruyko S (2020) End-to-end object detection with transformers European Conference on Computer Vision 2020 Springer, Cham, pp 213–229

Lee RS, Gimenez F, Hoogi A, Miyake KK, Gorovoy M, Rubin DL (2017) A curated mammography data set for use in computer-aided detection and diagnosis research. Sci Data 4:170177. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.177

Gonzales RCW, R. E (2008) Digital image processing, 3rd edn

He K ZX, Ren S, Sun J (2016) Deep residual learning for image recognitionProceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp 770–778

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45(2):228–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026

Tahmassebi A, Wengert GJ, Helbich TH et al (2019) Impact of machine learning with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of the breast for early prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and survival outcomes in breast cancer patients. Invest Radiol 54(2):110–117. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLI.0000000000000518

Qu YH, Zhu HT, Cao K, Li XT, Ye M, Sun YS (2020) Prediction of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer using a deep learning (DL) method. Thorac Cancer 11(3):651–658. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.13309

Sutton EJ, Onishi N, Fehr DA et al (2020) A machine learning model that classifies breast cancer pathologic complete response on MRI post-neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res 22(1):57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-020-01291-w

Liu MZ, Mutasa S, Chang P, Siddique M, Jambawalikar S, Ha R (2020) A novel CNN algorithm for pathological complete response prediction using an I-SPY TRIAL breast MRI database. Magn Reson Imaging 73:148–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2020.08.021

Ha R, Chin C, Karcich J et al (2019) Prior to initiation of chemotherapy, can we predict breast tumor response? Deep learning convolutional neural networks approach using a breast MRI tumor dataset. J Digit Imaging 32(5):693–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-018-0144-1

Cain EH, Saha A, Harowicz MR, Marks JR, Marcom PK, Mazurowski MA (2019) Multivariate machine learning models for prediction of pathologic response to neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancer using MRI features: a study using an independent validation set. Breast Cancer Res Treat 173(2):455–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4990-9

Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M et al (2014) Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet 384(9938):164–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62422-8

von Minckwitz G, Untch M, Blohmer JU et al (2012) Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol 30(15):1796–1804. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8595

Denkert C, von Minckwitz G, Darb-Esfahani S et al (2018) Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: a pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol 19(1):40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30904-X

Soliman H, Wagner S, Flake DD 2nd et al (2020) Evaluation of the 12-gene molecular score and the 21-gene recurrence score as predictors of response to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 27(3):765–771. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-08039-7

Sinn BV, Loibl S, Hanusch CA et al (2021) Immune-related gene expression predicts response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy but not additional benefit from PD-L1 inhibition in women with early triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 27(9):2584–2591. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3113

Korde LA, Somerfield MR, Carey LA et al (2021) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and targeted therapy for breast cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol 39(13):1485–1505. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.03399

Wang H, Zhang S, Yee D et al (2021) Impact of body mass index on pathological complete response following neoadjuvant chemotherapy in operable breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer 28(3):618–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-020-01194-w

Chou HH, Kuo WL, Yu CC et al (2019) Impact of age on pathological complete response and locoregional recurrence in locally advanced breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Biomed J 42(1):66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2018.10.007

La Forgia D, Vestito A, Lasciarrea M et al (2021) Response predictivity to neoadjuvant therapies in breast cancer: a qualitative analysis of background parenchymal enhancement in DCE-MRI. J Pers Med 11(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11040256

Park YH, Lal S, Lee JE et al (2020) Chemotherapy induces dynamic immune responses in breast cancers that impact treatment outcome. Nat Commun 11(1):6175. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19933-0

Tribukait B (2020) Early prediction of pathologic response to neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer: use of a cell-loss metric based on serum thymidine kinase 1 and tumour volume. BMC Cancer 20(2):440. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-06925-y

Bidard FC, Michiels S, Riethdorf S, Mueller V, Esserman LJ, Lucci A et al (2018) Circulating tumor cells in breast cancer patients treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 110(6):560–567. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy018

Han S, Choi JY (2020) Prognostic value of (18)F-FDG PET and PET/CT for assessment of treatment response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res 22(1):119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-020-01350-2

Skarping I, Fornvik D, Heide-Jorgensen U, Ryden L, Zackrisson S, Borgquist S (2020) Neoadjuvant breast cancer treatment response; tumor size evaluation through different conventional imaging modalities in the NeoDense study. Acta Oncol 59(12):1528–1537. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2020.1830167

Hylton NM, Blume JD, Bernreuter WK, Pisano ED, Rosen MA, Morris EA et al (2012) Locally advanced breast cancer: MR imaging for prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy–results from ACRIN 6657/I-SPY TRIAL. Radiology 263(3):663–672. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.12110748

Gu J, Polley EC, Denis M, Carter JM, Pruthi S, Gregory AV et al (2021) Early assessment of shear wave elastography parameters foresees the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 23(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-021-01429-4

Pu S, Wang K, Liu Y, Liao X, Chen H, He J et al (2020) Nomogram-derived prediction of pathologic complete response (pCR) in breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NCT). BMC Cancer 20(1):1120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07621-7

Meti N, Saednia K, Lagree A, Tabbarah S, Mohebpour M, Kiss A, et al (2021) Machine learning frameworks to predict neoadjuvant chemotherapy response in breast cancer using clinical and pathological features. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 5:66–80. https://doi.org/10.1200/CCI.20.00078

von Minckwitz G, Blohmer JU, Costa SD, Denkert C, Eidtmann H, Eiermann W et al (2013) Response-guided neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 31(29):3623–3630. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.0940

Symmans WF, Peintinger F, Hatzis C, Rajan R, Kuerer H, Valero V et al (2007) Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 25(28):4414–4422. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6823

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants in the study. The authors thank research nurse Lina Zander for excellent study coordination. We thank all personnel at Unilabs Malmö and Helsingborg for their excellent care of the study patients.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University. This study has received funding by grants from the Swedish Breast Cancer Group (BRO), Allmänna Sjukhusets i Malmö Stiftelse för bekämpande av cancer, and the Governmental Funding of Clinical Research within the National Health Services. Funding resources had no role in the study design, data collection, analyses, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is associated professor Daniel Förnvik, Lund University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Statistics and biometry

No complex statistical methods were necessary for this paper.

Informed consent

The general informed consents provided for the two cohorts at inclusion comprises the current study. More specifically, a general written consent, meeting the content of this current study, was obtained from the prospectively included patients at the time of inclusion. In accordance with the decision from the ethics committee regarding the retrospectively included patients, an “opt-out”-methodology was used and subsequently no written consent was obtained for these patients.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Lund, Sweden (committee’s reference number: 2014/13, 2014/521, and 2016/521).

Study subjects or cohorts overlap

Some study subjects or cohorts have been previously reported in:

Published:

- Skarping I, Fornvik D, Heide-Jorgensen U, et al. Mammographic density changes during neoadjuvant breast cancer treatment: NeoDense, a prospective study in Sweden. Breast. 2020 Oct;53:33–41. (Overlap: This study is based on the prospective cohort included in the current study. In this study, we investigated mammographic density (using VolparaTM) and its association with pCR).

- Skarping I, Fornvik D, Sartor H, et al. Mammographic density is a potential predictive marker of pathological response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019 Dec 30;19(1):1272. (Overlap: This study is based on the retrospective cohort included in the current study. In this study, we investigated mammogrpohic density (using Volpara TM) and its association with pCR)..

- Skarping I, Fornvik D, Heide-Jorgensen U, et al. Mammographic density as an image-based biomarker of therapy response in neoadjuvant-treated breast cancer patients. Cancer Causes Control. 2021 Mar;32(3):251–260. (Overlap: This study is based on the retrospective and prospective cohort included in the current study. In this study, we investigated mammographic density (BI-RADS) and its association with pCR).

- Skarping I, Fornvik D, Heide-Jorgensen U, et al. Neoadjuvant breast cancer treatment response; tumour size evaluation through different conventional imaging modalities in the NeoDense study. Acta Oncol. 2020 Dec;59(12):1528–1537. (Overlap: This study is based on the prospective cohort included in the current study. In this study, we investigated different aspects of conventional imaging (mammography, ultrasound and tomosynthesis) during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer).

Submitted: Skarping I, Blaabjerg Pedersen S, Förnvik D, Zackrisson S, Borgquist S. The association between body mass index and pathological complete response in neoadjuvant-treated breast cancer patients. (Overlap: This study is based on the retrospective and prospective cohort included in the current study. In this study, we investigated body mass index and its association with pCR)

Methodology

• prospective

• diagnostic or prognostic study, observational cohort study

• performed at one institution

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Skarping, I., Larsson, M. & Förnvik, D. Analysis of mammograms using artificial intelligence to predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients: proof of concept. Eur Radiol 32, 3131–3141 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-021-08306-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-021-08306-w