Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the need for additional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) following ultrasound (US) in patients with shoulder pain and/or disability and to compare the accuracy of both techniques for the detection of partial-thickness and full-thickness rotator cuff tears (RCT).

Methods

In 4 years, 5,216 patients underwent US by experienced musculoskeletal radiologists. Retrospectively, patient records were evaluated if MRI and surgery were performed within 5 months of US. US and MRI findings were classified into intact cuff, partial-thickness and full-thickness RCT, and were correlated with surgical findings.

Results

Additional MR imaging was performed in 275 (5.2%) patients. Sixty-eight patients underwent surgery within 5 months. US and MRI correctly depicted 21 (95%) and 22 (100%) of the 22 full-thickness tears, and 8 (89%) and 6 (67%) of the 9 partial-thickness tears, respectively. The differences in performance of US and MRI were not statistically significant (p = 0.15).

Conclusions

MRI following routine shoulder US was requested in only 5.2% of the patients. The additional value of MRI was in detecting intra-articular lesions. In patients who underwent surgery, US and MRI yielded comparably high sensitivity for detecting full-thickness RCT. US performed better in detecting partial-thickness tears, although the difference was not significant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Both ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can confirm a suspected partial-thickness or full-thickness rotator cuff tear. Both techniques have their advantages and disadvantages, and can be competitive and complementary at the same time. Factors of consideration concerning which technique should be used are availability of the test in a timely manner and the skill of the operators in carrying out and interpreting a given examination. In the literature the question which test constitutes the most accurate, cost effective, expedient or least invasive approach to the diagnosis of rotator cuff tears is still controversial. The question as to which is the best test should be answered on the basis of clinical experience, availability, and the expected sensitivity and specificity of the tests.

Although many investigators have evaluated the accuracy of US or MRI separately for the detection of partial-thickness (PTT) and full-thickness (FTT) rotator cuff tears, some have directly compared the two tests for the detection of full-thickness tears [1, 2], partial-thickness tears [3] or partial-thickness and full-thickness tears [4–10], but most with a relatively small number of patients [8–10].

In a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of clinical examinations with US and MRI in the detection of full-thickness and partial-thickness rotator cuff tears, Dinnes et al. [11] showed that US and MRI have comparably high accuracy for the detection of full-thickness tears. Based on the available literature, US is the method of first choice in the detection of rotator cuff tears in our hospital. In the case of unequivocal findings or clinical doubt, additional MRI is requested.

The purpose of this study was first to evaluate the need for additional MRI following US of the shoulder and secondly to evaluate and compare the accuracy of US and MRI for the detection of partial-thickness and full-thickness rotator cuff tears with surgery as the reference standard in a selected group of patients.

Materials and methods

Patients

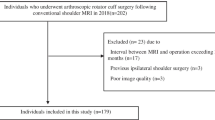

The inclusion criteria for this retrospective study were: (1) shoulder pain and/or disability for which the patients underwent plain radiography and US, (2) an additional MRI was performed and (3) subsequent surgery was carried out. The indications to perform MRI following US were suspicion for having intraarticular pathology (n = 94), inconclusive US examination due limited shoulder motion, obesity or undefined findings (n = 25), discrepancy between clinical and US findings (n = 77), and finally as a request for more diagnostic certainty (n = 18), and of the remaining patients (n = 61), the indication to perform MRI could not be determined. Patients were excluded when no surgery was performed and when the time intervals between US and MRI and/or US and surgery exceeded 5 months.

The study was performed in one tertiary teaching hospital. Between January 2004 and December 2007, 5,216 patients with shoulder pain and/or disability were referred by the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery or general practitioners and underwent US. Eighty-one were operated upon without MRI. Two hundred seventy-five patients (147 men and 128 women, with a mean age of 47 years, range 18–87 years) also underwent MRI of the shoulder, and 80 of the 275 patients subsequently had surgery. Twelve patients were excluded because the time interval between US and MRI or surgery exceeded 5 months. The remaining 68 patients (37 men and 31 women, with a mean age of 48 years, range 24–81 years) formed the study group whose data were analysed retrospectively.

Patients were evaluated for the presence of rotator cuff tears. Findings were classified into intact cuff, partial-thickness and full-thickness rotator cuff tears, and correlated with surgical findings, which were considered the gold standard. The time interval between the US examination and MRI ranged from 0 to 98 days (mean 41 days). The time interval between US examination and surgery ranged from 5 to 147 days (mean 99 days) and between MRI and surgery 5 to 139 days (mean 59 days).

Ultrasound

All US examinations were performed by two musculoskeletal radiologists (MR, GJ), using a APLIO device (Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with a 7.5–14-MHz linear array transducer (PLF-805ST). Real-time imaging of the shoulder was performed in a standardised fashion as described in the literature [12]. Established criteria were used for the diagnosis of a partial-thickness or full-thickness rotator cuff tear [13–15].

Magnetic resonance imaging

All MRI examinations were performed with an 1.5-T MR system (Signa Horizon, GE, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands). Of the 80 patients, 34 patients underwent MR arthrography (MRA) and 46 patients conventional MRI. The conventional MRI shoulder protocol consisted of oblique coronal T2-weighted with fat suppression (2.48 min) and T1-weighted turbo spin echo images (5.58 min), oblique sagittal T2-weighted turbo spin echo images without fat suppression (2.36 min) and transverse T1-weighted turbo spin echo images (4.52 min). A field of view of 16 cm was used, the slice thickness was 3 mm, the imaging matrix was 320 × 224, and three signals were averaged for each pulse sequence.

The MRA protocol consisted of 3D-gradient T1-weighted (SPGR) oblique coronal and axial images (5 min), which were reconstructed, if indicated, in any other desired plane. SPGR 3D imaging (TR: 51 ms; TE: 7 ms; 1 acquisition; 256 × 256 matrix; FOV: 22 cm, slice thickness 2.8 mm) with 2.8-mm consecutive slices was used, and coronal T2-weighted turbo spin echo images (2.30 min), sagittal T2-weighted turbo spin echo images (2.40 min) and the ABER view with coronal T1-weighted turbo spin echo images with fat suppression (4.15 min).

Overall MRA imaging time was 19 min 30 s.

The MRI examinations were blinded and retrospectively evaluated by the same experienced musculoskeletal radiologists (MR, GJ) who performed the US examinations, at a later date, to avoid any effect on the interpretation of findings at MRI by the recent ultrasound examination. This set-up was chosen to exclude the potential bias of having readers with a different level of knowledge of anatomy and pathological features of the shoulder.

Established criteria were used for the diagnosis of a partial-thickness or full-thickness rotator cuff tear [16–19]. An example of a full-thickness rotator cuff tear as demonstrated by US and MRI is shown in Fig. 1.

Full-thickness rotator cuff tear. (a) Ultrasound appearance of a full-thickness tear (arrows) at the insertion of the supraspinatus tendon (SSP). GT = greater tuberosity. (b) The corresponding oblique coronal gradient T1-weighted MR arthrography image, showing the same configuration of the full-thickness tear (arrows) of the supraspinatus tendon (SSP). GT = greater tuberosity

Surgery

In all study subjects, surgery (arthroscopy or open) was performed by a subspecialty-trained shoulder surgeon, who was aware of the US and MRI findings. The presence or absence of a partial-thickness or full-thickness rotator cuff tears and intraarticular lesions were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Using cross tabulations, the presence or absence of a partial-thickness or full-thickness rotator cuff tear was compared among US, MRI and surgery. Based on the tables, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, the positive predictive value and the negative predictive value were calculated.

The agreement between the results of US and MRI in the detection of rotator cuff tears was determined by calculating a kappa coefficient. Differences in scoring between US and MRI were tested for statistical significance using a marginal homogeneity test (or McNemar-Bowker test) for related samples. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 14.0.2 for Windows (Chicago, IL).

Results

At surgery, 22 full-thickness and 9 partial-thickness rotator cuff tears were found (Table 1). US correctly depicted 29 (94%) of the 31 rotator cuff tears: 21 (95%) of the 22 full-thickness tears and 8 (89%) of the 9 partial-thickness tears (Tables 1 and 2). MRI correctly depicted 28 (90%) of the 31 rotator cuff tears: all 22 (100%) full-thickness tears and 6 (67%) of the 9 partial-thickness tears (Tables 1 and 2).

The overall accuracy of US and MRI in diagnosing full-thickness and partial-thickness tears and intact rotator cuffs (Table 1) was 78% (53/68) and 79% (54/68) with a 95% confidence interval of 66%-87% and 68%-88%, and an overall specificity of 65% (24/37) and 70% (26/37), respectively.

Table 2 lists the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and positive and negative predictive values for both diagnostic imaging techniques in the detection of partial-thickness and full-thickness rotator cuff tears. The agreement between US and MRI was high: the kappa coefficient was calculated to be 0.78 (SE = 0.06) (Table 3). The differences in the scoring between the two diagnostic tests were not statistically significant: the marginal homogeneity test was 0.15, suggesting that the two tests have comparable diagnostic value.

For the detection of full-thickness rotator cuff tears with US and MRI (Fig. 1), there was a high degree of sensitivity, specificity and accuracy (95%, 93%, 94% for US and 100%, 91%, 94% for MRI, respectively). The full-thickness rotator cuff tears varied in size from 0.5 to 3.0 cm. US and MRI showed three and four false-positive full-thickness tears, respectively (Table 1). US showed one false-negative study (Fig. 2). In this case MRI showed a full-thickness tear, which was proven surgically, whereas with US it was identified as an extended (>50%) partial-thickness rotator cuff tear (Fig. 2).

Sonographically underestimated full-thickness rotator cuff tear. Long (a) and short (b) axis ultrasound section showing an intratendinous partial-thickness tear (arrows) at the insertion of the supraspinatus tendon (SSP). GT = greater tuberosity, H = humeral head. (c) The corresponding oblique coronal gradient T1-weighted MR arthrography image, showing the same intratendinous extending tear (arrows) of the supraspinatus tendon (SSP), but also leakage of intraarticularly injected contrast media to the subacromial–subdeltoid bursa (arrowheads), suggestive of a full-thickness SSP tear, which was surgically confirmed. GT = greater tuberosity

For the detection of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears, there was a comparable diagnostic value for US and MRI with a specificity and accuracy of 80%, 81% and 86%, 84%, respectively. The sensitivity of US (89%) for the detection of partial-thickness tears seems to be a little better than that of MRI (67%), but these percentages are based on only nine cases, and the difference is not significant. These partial rotator cuff tears were located superficially, at the articular side (n = 8) and bursal side (n = 1). Both US and MRI incorrectly overestimated one partial-thickness tear as a full-thickness rotator cuff tear (Table 1). With conventional MRI, two partial-thickness tears were incorrectly underestimated as no tear (Fig. 3).

Partial-thickness rotator cuff tear in the supraspinatous tendon (SSP) underestimated with conventional MRI. (a) Ultrasound showed an intratendinous partial-thickness tear (arrow) in the insertion (i.e., at the footprint) of the SSP, which was confirmed surgically. (b) The corresponding oblique coronal T2-weighted fat saturated MR image shows high signal in the SSP, which was wrongly interpreted as tendinosis. GT = greater tuberosity

Surgery demonstrated no rotator cuff tears in 37 shoulders (Table 4). US and MRI correctly demonstrated no tears in 24 and 26 shoulders, respectively (Table 4). However, US and MRI suggested 2 and 3 full-thickness and 11 and 8 partial-thickness rotator cuff tears in the remaining 15 and 13 shoulders, respectively, which were not confirmed by surgery.

In 7 cases both US (7/11) and MRI (7/8) demonstrated a false-positive PTT (Fig. 4). In five of these cases, the PTT was located intratendinously (Fig. 4) and two at the articular site near to the insertion of the supraspinatus tendon. In four other false-positive PTT cases, US demonstrated a PTT, whereas MRI and surgery did not. In three of these cases MRI demonstrated signal distortion in the tendon, which was interpreted as tendinosis. In one of the eight false-positive cases with MRI, US as well as surgery was negative. Retrospective analyses of the MRI findings are more suggestive of tendinosis than of PTT.

False-positive partial-thickness rotator cuff tear in the supraspinatous tendon (SSP). Both ultrasound (a) and the corresponding oblique coronal T2-weighted fat saturated MR image (b), show an undersurface partial-thickness tear (arrow) in the insertion (i.e., at the footprint) of the SSP. However, this finding was not confirmed during surgery. GT = greater tuberosity

In the two cases in which US identified an FTT and surgery demonstrated no tear, MRI also identified a FTT. In one case US and MRI showed an FTT, whereas surgery showed a PTT (Table 1). In three cases MRI demonstrated an FTT, while surgery showed no tear; US showed in two cases an FTT as well, but no tear in the other case (Table 3).

In seven patients MRI changed the surgical strategy because in six patients a labral tear and in one patient a glenohumeral ligament tear was found.

Discussion

In the present study we compared the accuracy of US and MRI in the detection of rotator cuff tears in patients who underwent both imaging techniques. In our institution, US is the method of choice in evaluating patients with shoulder complaints. As in other countries, the use of US has increased significantly [20]. In our study the use of US obviates the need for further imaging in 95% of the cases.

The high lifetime prevalence of shoulder pain of 66% [21] and the moderate reliability and reproducibility of clinical history and clinical examination may be an explanation for the large number of US examinations. In this study we focussed on the presence or absence of rotator cuff tears. Other diagnoses that are often made with US, e.g., subacromial bursitis and impingement syndrome, were not evaluated. The combination of clinical history, clinical examination and ultrasound fulfil the need for diagnostic certainty and permit the initiation of therapy in most cases. The disadvantage of the liberal use of US may be a large number of negative findings as was an additional finding of our study, because the indication to perform US of the shoulder was shoulder pain and/or disability instead of suspicion for having a rotator cuff tear. Another disadvantage could be a large number of false-positive findings, as there is a chance of up to 50% of finding abnormalities in an asymptomatic shoulder [22]. Therefore, good clinical examination remains of utmost importance in the evaluation of patients with shoulder complaints.

Another purpose of this retrospective study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of US in cases in which additional MRI was requested and to compare these two techniques.

US and MRI findings were compared with surgical findings and appeared comparably accurate in diagnosing full-thickness tears (94% and 94%, respectively) and less, but also comparably accurate for the detection of partial-thickness tears (81% and 84%, respectively). Our findings substantiate those reported by Dinnes et al. [11] and Teefey et al. [9], who showed that US and MRI have comparable accuracy for identifying partial-thickness and full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Although Teefey et al. [9] performed a prospective study, while we retrospectively analysed findings in a more diverse patient population from daily practice, both studies show that MRI of the shoulder provides, with regard to the rotator cuff, little additional information following an US examination. However, in our selected study group in 7 (10%) of the 68 patients MRI detected intraarticular pathology, which changed the therapy strategy. Furthermore, for some surgeons MRI may have additional value to assess fatty infiltration of the rotator cuff; however, we agree with others that US can depict fatty infiltration and atrophy of the rotator cuff as reliably as MRI [23, 24]. Although it is known that US and MRI have comparable accuracy for identifying and measuring the size of full-thickness and partial-thickness rotator cuff tears [9], MRI may be used to define the precise location and extent of a rotator cuff tear; however, this was not the case in our series.

There are several limitations of our study. A potential drawback is the operator dependency of US [25–27] and MRI [16, 28]. In an unpublished study we evaluated the learning curve and the interobserver variability of US in a series of 200 patients. If US was performed in a standardised manner, the interobserver agreement was excellent. The kappa coefficient was calculated to be 0.80 (SE = 0.05).

Furthermore, the study design was prone to bias. For example, the study population of the 207 patients who underwent US and MRI but did not undergo surgery probably differs from the 68 patients who were operated upon (selection bias). On the other hand, the agreement between US and MRI in the group of 207 patients was 86%, approximately similar to that in the group of 68 patients (85%), indicating that the result of our study was not biased by this selection.

Also, a verification or workup bias was present because imaging findings were known by the surgeon and influenced the decision whether or not to treat surgically and thus influenced patient selection. Preoperative knowledge of the imaging results caused diagnostic review bias, as a result of a more thorough exploration of the cuff in order to find a RCT identified using US or MRI, which of course influences the gold standard.

The value of MRI as a follow-up examination is probably underestimated due to the low threshold to request US and consequently overuse of US.

Finally, there is an imperfect standard bias, which occurs when the reference standard is not 100% accurate. In our opinion the so-called gold standard is such a potential cause of bias. Waldt et al. [29] showed that the diagnosis of small partial-thickness tears are restricted because of difficulties in the differentiation among fibre tearing, tendinitis, synovitic changes and superficial fraying at tendon margins. Interobserver variability is also introduced by varying definitions and/or synonyms used by both sonologists and surgeons. Kuhn et al. [30] showed that six currently described rotator cuff classification systems have demonstrated little interobserver agreement among experienced shoulder surgeons. In our experience in these studies the ‘gold standard’ was more a ‘silver handicap’, especially with regard to the detection of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears (Fig. 4). When we assume that the seven cases in which both US and MRI showed a non-surgically proven PTT were true-positives, then the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV and NPV of US would increase to 94%, 90%, 91%, 75%, 98%, and those of MRI to 81%, 98%, 94%, 93%, 94%, respectively, which is almost as good as the accuracy for diagnosing full-thickness rotator cuff tears. The imperfect standard bias may cause an underestimation of the reported accuracy for diagnosing partial-thickness rotator cuff tears with US and MRI.

At the RSNA meeting of 2008 a special focus session was dedicated to the question “Musculoskeletal US: Has the Time Come?” We have demonstrated that diagnostic US of the shoulder in patients with periarticular complaints in our institution performed by a radiologist fulfils the clinical need for diagnosis and further management. We are of the opinion that if musculoskeletal radiologists ignore increasing requests for US of the shoulder, these examinations will soon be performed by rheumatologists [27, 31], orthopaedic surgeons [32–34], physiotherapists or family physicians who have been reported to be able to performing US of the shoulder equally well.

In summary, in patients with periarticular shoulder pain, US is a reliable diagnostic tool that obviates the need for further imaging in most cases. Our study established that US and MRI yield comparably high sensitivity, diagnostic accuracy and positive predictive value in detecting full-thickness rotator cuff tears. In detecting partial-thickness rotator cuff tears both tests are less accurate; however, US appears to be more sensitive than MRI.

Finally, following US of the shoulder performed by a dedicated radiologist, MRI offers little additional value, with regard to the detection of rotator cuff tears. Of course local setting and other factors such as equipment availability, personal expertise and preference, patient preference [35] and cost effectiveness [36] may play a role in choosing which imaging technique will be used.

References

Chang CY, Wang SF, Chiou HJ, Ma HL, Sun YC, Wu HD (2002) Comparison of shoulder ultrasound and MR imaging in diagnosing full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Clin Imaging 26:50–54

Swen WA, Jacobs JW, Algra PR et al (1999) Sonography and magnetic resonance imaging equivalent for the assessment of full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Arthritis Rheum 42:2231–2238

Vlychou M, Dailiana Z, Fotiadou A, Papanagiotou M, Fezoulidis IV, Malizos K (2009) Symptomatic partial rotator cuff tears: diagnostic performance of ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging with surgical correlation. Acta Radiol 50:101–105

Nelson MC, Leather GP, Nirschl RP, Pettrone FA, Freedman MT (1991) Evaluation of the painful shoulder. A prospective comparison of magnetic resonance imaging, computerized tomographic arthrography, ultrasonography and operative findings. J Bone Joint Surg Am 73-A:707–716

Bachmann GF, Melzer C, Heinrichs CM, Mohring B, Rominger MB (1997) Diagnosis of rotator cuff lesions: comparison of US and MRI on 38 joint specimens. Eur Radiol 7:192–197

Kenn W, Hufnagel P, Muller T et al (2000) Arthrography, ultrasound and MRI in rotator cuff lesions: a comparison of methods in partial and small complete ruptures. Fortschr Roentgenstr 172:260–266

Ferrari FS, Governi S, Burresi F, Vigni F, Stefani P (2002) Supraspinatus tendon tears: comparison of US and MRI arthrography with surgical correlation. Eur Radiol 12:1211–1217

Martin-Hervas C, Romero J, Navas-Acien A, Reboiras JJ, Munuera L (2001) Ultrasonographic and magnetic resonance images of rotator cuff lesions compared with arthroscopy or open surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 10:410–415

Teefey SA, Rubin DA, Middleton WD, Hildebolt CF, Leibold RA, Yamaguchi K (2004) Detection and quantification of rotator cuff tears. Comparison of ultrasonographic, magnetic resonance imaging, and arthroscopic findings in seventy-one consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86-A:708–716

Fotiadou A, Vlychou M, Papadopoulos P, Karataglis DS, Palladas P, Fezoulidis IV (2008) Ultrasonography of symptomatic rotator cuff tears compared with MR imaging and surgery. Eur J Radiol 68:174–179

Dinnes J, Loveman E, McIntyre L, Waugh N (2003) The effectiveness of diagnostic tests for the assessment of shoulder pain due to soft tissue disorders: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 7:1–166

Rutten MJ, Maresch BJ, Jager GJ, Blickman JG, van Holsbeeck MT (2007) Ultrasound of the rotator cuff with MRI and anatomic correlation. Eur J Radiol 62:427–436

van Holsbeeck MT, Kolowich PA, Eyler WR et al (1995) US depiction of partial-thickness tear of the rotator cuff. Radiology 197:443–446

Teefey SA, Hasan SA, Middleton WD, Patel M, Wright RW, Yamaguchi K (2000) Ultrasonography of the rotator cuff. A comparison of ultrasonographic and arthroscopic findings in one hundred consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 82-A:498–504

Rutten MJ, Jager GJ, Blickman JG (2006) Ultrasound of the rotator cuff: pitfalls, limitations and artifacts. Radiographics 26:589–604

Balich SM, Sheley RC, Brown TR, Sauser DD, Quinn SF (1997) MR imaging of the rotator cuff tendon: interobserver agreement and analysis of interpretive errors. Radiology 204:191–194

Jbara M, Chen Q, Marten P, Morcos M, Beltran J (2005) Shoulder MR arthrography: how, why, when. Radiol Clin North Am 43:683–692

Kassarjian A, Bencardino JT, Palmer WE (2006) MR imaging of the rotator cuff. Radiol Clin North Am 44:503–523

Seibold CJ, Mallisee TA, Erickson SJ, Boynton MD, Raasch WG, Timins ME (1999) Rotator cuff: Evaluation with US and MR Imaging. Radiographics 19:685–705

Awerbuch MS (2008) The clinical utility of ultrasonography for rotator cuff disease, shoulder impingement syndrome and subacromial bursitis. Med J Aust 188:50–53

Luime JJ, Koes BW, Hendriksen IJ et al (2004) Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population; a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol 33:73–81

Milgrom C, Schaffler M, Gilbert S, van Holsbeeck M (1995) Rotator cuff changes in asymptomatic adults: the effect of age, hand dominance, and gender. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 77:296–298

Khoury V, Cardinal E, Brassard P (2008) Atrophy and fatty infiltration of the supraspinatus muscle: sonography versus MRI. Am J Roentgenol 190:1105–1111

Strobel K, Hodler J, Meyer DC, Pfirrmann CW, Pirkl C, Zanetti M (2005) Fatty atrophy of supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles: accuracy of US. Radiology 237:584–589

Middleton WD, Teefey SA, Yamaguchi K (2004) Sonography of the rotator cuff: Analysis of interobserver variability. Am J Roentgenol 183:1465–1468

O’Connor PJ, Rankine J, Gibbon WW, Richardson A, Winter F, Miller JH (2005) Interobserver variation in sonography of the painful shoulder. J Clin Ultrasound 33:53–56

Scheel AK, Schmidt WA, Hermann KG et al (2005) Interobserver reliability of rheumatologists performing musculoskeletal ultrasonography: results from a EULAR “Train the Trainers” course. Ann Rheum Dis 64:1043–1049

Robertson PL, Schweitzer ME, Mitchell DG et al (1995) Rotator cuff disorders: interobserver and intraobserver variation in diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiology 194:831–835

Waldt S, Bruegel M, Mueller D et al (2007) Rotator cuff tears: assessment with MR arthrography in 275 patients with arthroscopic correlation. Eur Radiol 17:491–498

Kuhn JE, Dunn WR, Ma B et al (2007) Interobserver agreement in the classification of rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med 35:437–441

Naredo E, Moller I, Moragues C et al (2006) Interobserver reliability in musculoskeletal ultrasonography: results from a “Teach the Teachers” rheumatologist course. Ann Rheum Dis 65:14–19

Iannotti JP, Kwon YW (2005) Management of persistent shoulder pain: a treatment algorithm. Am J Orthop 34:16–23

Roberts CS, Galloway KP, Honaker JT, Hulse G, Seligson D (1998) Sonography for the office screening of suspected rotator cuff tears: early experience of the orthopedic surgeon. Am J Orthop 27:503–506

Al-Shawi A, Badge R, Bunker T (2008) The detection of full thickness rotator cuff tears using ultrasound. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 90:889–892

Middleton WD, Payne WT, Teefey SA, Hildebolt CF, Rubin DA, Yamaguchi K (2004) Sonography and MRI of the shoulder: Comparison of patient satisfaction. Am J Roentgenol 183:1449–1452

Parker L, Nazarian LN, Carrino JA et al (2008) Musculoskeletal imaging: medicare use, costs, and potential for cost substitution. J Am Coll Radiol 5:182–188

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Rutten, M.J.C.M., Spaargaren, GJ., van Loon, T. et al. Detection of rotator cuff tears: the value of MRI following ultrasound. Eur Radiol 20, 450–457 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-009-1561-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-009-1561-9