Abstract

Targeted efforts to better understand the barriers and facilitators of stakeholders and healthcare settings to implementation of exercise and education self-management programmes for osteoarthritis (OA) are needed. This study aimed to explore the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:D), a supervised group guideline-based OA programme, across Irish public and private healthcare settings. Interviews with 10 physiotherapists (PTs; 8 public) and 9 people with hip and knee OA (PwOA; 4 public) were coded by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) constructs in a case memo (summary, rationale, quotes). The strong positive/negative implementation determinants were identified collaboratively by rating the valence and strength of CFIR constructs on implementation. Across public and private settings, PTs and PwOA strongly perceived GLA:D Ireland as evidence-based, with easily accessible education and modifiable marketing/training materials that meet participants’ needs, improve skills/confidence and address exercise beliefs/expectations. Despite difficulties in scheduling sessions (e.g., work/caring responsibilities), PTs in public and private settings perceived advantages to implementation over current clinical practice (e.g., shortens waiting lists). Only PTs in public settings reported limited availability of internal/external funding, inappropriate space, marketing/training tools, and inadequate staffing. Across public and private settings, PwOA reported adaptability, appropriate space/equipment and coaching/supervision, autonomy, and social support as facilitators. Flexible training and tailored education for stakeholders and healthcare settings on guideline-based OA management may promote implementation. Additional support on organising (e.g., scheduling clinical time), planning (e.g., securing appropriate space, marketing/training tools), and funding (e.g., accessing dedicated internal/external grants) may strengthen implementation across public settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a major public health burden [1]. Several evidence-based guidelines for OA recommend exercise and education for self-management as first-line treatments [2, 3]. However, less than 40% of people with hip and knee OA (PwOA) receive guideline-based first-line treatments [4]. Global inequities and challenges within healthcare settings and service delivery, ageing populations, and higher obesity and physical inactivity rates may contribute to this evidence-to-practice gap [5,6,7]. Targeted efforts to strengthen the implementation of guideline-based healthcare services that may alleviate the burden of OA must be encouraged.

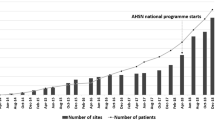

Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:D) is a supervised group education and neuromuscular exercise self-management programme for OA [8]. Findings from 28,370 PwOA in the GLA:D data collection registry (Denmark, Canada, Australia) suggest that participation reduces pain intensity by 26–33% and improves quality of life by 12–26% [9]. To optimise healthcare service delivery for OA, GLA:D was cross-culturally adapted for implementation in Irish public and private healthcare settings using a participatory health research approach [10, 11]. In Ireland, a two-tiered healthcare system exists (closest to the UK and Australia), where cost and access to public services are associated with an individual’s circumstance (e.g., people with low incomes may be allocated medical cards granting access to some services for free) [12]. Approximately, 33% of the population have a medical card and 46% are covered by voluntary private health insurance, which may provide faster access to and better choice of providers/services [13]. Furthermore, rheumatologists are currently under-staffed in Ireland, with per capita numbers one of the lowest in Europe [14]. A better understanding of the multilevel factors of stakeholders and healthcare settings that influence the implementation of new healthcare services is needed to address the gap in guideline-based OA management.

Implementation science and the application of established theoretical frameworks consider multifactorial barriers and facilitators to programme implementation [15, 16]. Previously, the implementation of GLA:D Canada and GLA:D Australia were evaluated using mixed methods [17] and surveys [18], respectively. Implementation determinants, such as costs and training, were reported using the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework. However, problems associated with applying RE-AIM have been highlighted regarding reporting of recruitment methods and/or costs and resources required [19]. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) is a comprehensive implementation science framework comprising of five domains: “Innovation”, “Outer Setting”, “Inner Setting”, “Individuals”, and “Implementation Process” [20]. Previously, CFIR has been used to identify the implementation barriers and facilitators of guideline-based programmes that may improve other healthcare services, including older adults with disabilities and frailty [21, 22]. CFIR’s inclusion of a broad range of implementation determinants may be useful across different healthcare systems, services, stakeholders, and societies globally. Thus, this study aims to use CFIR to qualitatively explore the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a supervised group neuromuscular exercise and education self-management programme for OA (GLA:D Ireland) across public and private healthcare settings. The implementation determinants associated with a strong positive/negative influence on stakeholders and healthcare settings will be identified.

Methods

GLA:D Ireland

This qualitative study, as part of a larger study (IMPACT: IMPlementation of osteoArthritis Clinical guidelines Together), was conducted between 2022 and 2023. A convenience sample of PTs from different Irish healthcare settings was invited to participate in GLA:D training, with additional courses advertised nationally, across networks and clinical interest groups [10]. These PTs participated in a training course, between October 2021 and May 2022, developing essential skills and knowledge on guideline-based OA management and GLA:D Ireland protocol (e.g., delivering education, supervising neuromuscular exercise, and using the online data collection registry) [10]. After completion of the course, GLA:D-trained PTs used existing/new referral sources to invite PwOA (≥ 18 years old) to participate. Criteria excluding participation were the non-OA cause of symptoms (e.g., tumour), or other symptoms that are more pronounced than OA (e.g., fibromyalgia) [10]. GLA:D Ireland consisted of face-to-face supervised group education sessions (n = 2) and neuromuscular exercise sessions (n = 12 (twice a week)).

Consolidated framework for implementation research

Implementation was assessed retrospectively, using CFIR as an evaluation framework. CFIR offers a structured approach developed from multiple implementation theories to promote effective implementation [20]. CFIR consists of 60 constructs sorted under five domains: “Innovation” “Outer Setting”, “Inner Setting”, “Individuals” and “Implementation Process”. Table 1 presents further details on the definitions and operalisation of CFIR domains.

Sample

Inclusion criteria were (1) PTs who have implemented GLA:D Ireland and (2) PwOA who have taken part in GLA:D Ireland. Participants were contacted by email and maximum variation sampling was applied to include a balance of gender, affected joint, duration of pain, and healthcare settings to collect data from the widest range of implementation experiences. The sampling of new participants continued until data saturation.

Data collection

A semi-structured interview guide including a range of open-ended questions/probes on participant experiences that were an implementation barrier and/or facilitator was developed using CFIR and prior literature [17] and is presented in Online Resource 1. The guide was tailored to gather specific information on GLA:D Ireland, with CFIR constructs informing operalisation. A pilot interview to test and refine the guide was undertaken. No revisions were necessary. Questions were related to programme delivery, logistics, fidelity, appropriateness and sustainability. Participant descriptions were probed to understand how implementation experiences related to each CFIR construct and the study aim. Interviews were conducted by a single investigator (AB) via a telephone call or online videoconferencing software Microsoft Teams (Microsoft Teams v.1.6, USA). AB is a PhD candidate evaluating the implementation of GLA:D Ireland, has trained in qualitative methodologies, and had no other interactions with participants. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by AB, and personal identifiers were removed. Written consent was obtained from all participants prior to interviews. To minimise bias, AB reflexively assessed pre-existing perspectives using field notes to document decisions.

Data analysis

Demographic characteristics were analysed quantitatively using frequency distributions. Interview data were interpreted by at least two investigators using a deductive content analysis approach first, appropriate for analysing data using an existing framework (CFIR) [23]. Any additional themes identified using an inductive approach were labelled as appropriate. Firstly, investigators (AB, CF, MG) familiarised themselves with the data through multiple readings of transcripts. Following this, transcripts were transferred to and managed with NVivo10 (QSR International). An NVivo10 template, pre-populated with CFIR construct definitions, was used [24] to develop codes for each transcript [25]. Based on these codes, case memos for each transcript including summary statements with quotations were developed and organised by each CFIR construct. This was a highly iterative process and involved refining CFIR constructs continuously within the scope of the study until the case memo for each transcript was complete (i.e., until data saturation). Next, each CFIR construct within each case memo was subjected to a rating process using a consensus approach [24, 25]. The ratings reflected the valence (positive/negative influence) and strength of each CFIR construct based on each case memo. CFIR constructs were rated as either: missing data (M), mixed positive and negative (X), strong negative (-2) or positive (+ 2), weak negative (-1) or positive (+ 1), or neutral/no influence on implementation (0). Table 2 presents further details on the criteria used to assign ratings. Once all CFIR constructs for all case memos were rated, we created a matrix that listed all the ratings using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Excel v.16.59, USA). Once consensus on overall ratings for each CFIR construct was reached, we reviewed overall ratings to discern patterns that reflected participants’ descriptions. This allowed us to take a collaborative approach to identify implementation barriers and facilitators. During each step of the analysis, investigators continuously reviewed the codes and associated ratings to identify pre-existing biases or assumptions, to ensure they reflected participants’ descriptions of implementation barriers and facilitators, and to resolve any discrepancies.

Results

Sample

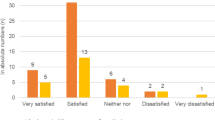

Interviews were conducted between 2022 and 2023 (i.e., within six months of having completed their respective GLA:D Ireland programmes). In total, 20 PTs and 35 PwOA were invited and of these, 10 PTs (50.0%) and 9 PwOA (25.7%) responded and agreed to be interviewed. The PT interviews ranged in duration from 29 to 54 min (telephone call n = 1), PwOA from 22 to 37 min (telephone call n = 9), and no repeat interviews were conducted. The majority of participants were female (PTs: 60.0%; n = 6 and PwOA: 77.8%; n = 7), living in the province of Connacht (PTs: 40.0%, n = 4) and Leinster (PwOA: 55.6%, n = 5), and reported public (PTs: 80.0%, n = 8) or private (PwOA: 55.6%, n = 5) healthcare settings. Detailed participant demographic characteristics can be found in Table 3.

CFIR domains

Of the total 60 CFIR constructs, PTs identified 11 as barriers ( – 2 or – 1), 33 as facilitators (+ 2 or + 1), 4 as both barriers and facilitators (X), 2 as neutral (0), and 10 as missing too much data to discern an influence on implementation (M). PwOA identified 2 CFIR constructs as barriers, 28 as facilitators, 2 as neutral, and 28 as missing. More facilitators were identified than barriers for both PwOA and PTs in the CFIR domains of “Innovation”, “Inner Setting”, “Individuals” and “Implementation Process”. However, more barriers were identified in the CFIR domain of “Outer Setting” for PTs. For a complete list of barriers and facilitators with associated ratings, see Online Resource 2.

Tables 4 and 5 list illustrative quotes for CFIR constructs with a (1) strong positive/negative and (2) mixed positive and negative influence on implementation for PTs and PwOA, respectively. PTs identified nine CFIR constructs as strong positive, 1 as strong negative, and 4 as mixed positive and negative influences on implementation. PwOA identified 15 CFIR constructs as strong positive influences on implementation. No CFIR constructs were identified by PwOA as strong negative or mixed positive and negative influences on implementation.

Innovation

“Innovation Evidence-Base” and “Innovation Design” were strong facilitators for all participants. PTs and PwOA believed that the programme was supported by peers/colleagues, up-to-date research, previous clinical/participant experience, and in line with current guidelines. Both reported that the programme marketing and training materials included high quality, effective resources that were designed to be easily accessible.

PT 9: “The quality of the programme is really good and it’s well-structured and evidence-based.”

PwOA 6: “If you found a particular exercise didn’t suit you, they had an alternative one that you could do.”

Only PTs reported “Innovation Relative Advantage” as a strong facilitator citing a clear advantage to implementing the programme. They perceived that the programme offers an alternative treatment/care pathway for PwOA, shortens waiting lists and encourages first-line treatment success.

PT 10: “On average, these patients would be seen once a month for three months, whereas now you’re definitely getting a more kind of an intensive input granted over a shorter period of time.”

Only PwOA reported “Innovation Adaptability” as a strong facilitator acknowledging that the programme materials and equipment were easily modifiable, and the structure could be tailored to fit participant needs.

PwOA 7: “You didn’t have to go and buy special equipment; you could use your stairs for the steps.”

Outer setting

“Financing” was both a barrier and facilitator only for PTs. They perceived that while external funding (e.g., grants, reimbursements) is available to implement new healthcare services, access may be limited, and long-term sustainability is challenging.

PT 1: “Maybe I do one in the morning somewhere and one in the afternoon somewhere else, but probably just won’t work out more because of funding than anything else.”

Only PwOA reported “Local Attitudes” as a strong facilitator citing previous exercise beliefs/expectations and PTs encouragement to engage in the programme.

PwOA 4: “Exercise has always been a huge part of my life.”

Inner setting

“Access to Knowledge and Information” was a strong facilitator for all participants. PTs and PwOA perceived that guidance and training to implement the programme was accessible, timely, and informative.

PT 3: “The practical component of it and practicing on each other and practicing teaching it. Even though the exercises are simple, it’s just getting the confidence in doing them and getting a structure with doing them.”

PwOA 4: “And X always was great at sending YouTube videos so you could actually watch, because I’ve been doing them religiously and consistently, I know how to do them, but that was handy at the start, so that you could just go back to them to refresh your memory on how to do the exercise.”

Only PTs found “Tension for Change” as a strong facilitator. They described first-hand experiences with PwOA that demonstrate a strong need for change in the healthcare setting.

PT 2: “Always see so much osteoarthritis, especially hip and knee. I think it could definitely help with our waiting list.”

“Information Technology and Work Infrastructure”, and “Available Funding” acted as both barriers and facilitators only for PTs. They found that while roles/responsibilities of individuals in the healthcare settings may be well-organised, technical systems, staffing levels, and lack of consistently available internal funding may not support day-to-day activities.

PT 2: “Management had been pretty good, just good timing that they had funding to buy stuff.”

Only PwOA reported “Physical Infrastructure”, “Recipient-Centredness”, and “Relative Priority” as strong facilitators. PwOA perceived that the features and layout of the healthcare setting supported functional performance as well as programme delivery. Additionally, they found that they received care that addressed their needs (e.g., supervision and autonomy). Further, supporting participation in the programme may be important.

PwOA 9: “I made up my mind that this is a chance to help me, to help myself, and that’s the way I looked at it, and that’s what worked out”

Individuals: roles

Only PwOA found “Implementation Leads” as a strong facilitator. PwOA believed that the programme was well-supported by individuals with expert knowledge.

PwOA 2: “The whole thing was conducted in a very professional manner.”

Individuals: characteristics

“Need” was a strong facilitator for PTs and PwOA. Both believed that the programme met the needs of participants including, functional improvements, pain reduction, increased strength and stamina and social engagement.

PT 8: “From a social point of view, they did so well. From a PT point of view, they did very well. From the exercise point of view, they did very well. And from functionally in their activities of daily living, they did very well.”

PwOA 1: “I bought myself a step. So, I’ve been stepping on the step and stepping over the step.”

“Capability” and “Motivation” were strong facilitators only for PTs. They found that participants were highly committed to their role in the programme, understood the exercise and education self-management strategies, and had high confidence in their skills and knowledge.

PT 9: “I didn’t experience many challenges because I have done a lot of classes before.”

Only PTs found “Opportunity” as a strong barrier. PTs perceived a lack of time and resources to implement the programme. Further, work/family commitments and the logistics of recruiting participants and scheduling appointments were reported as barriers.

PT 5: “Time is a challenge because resources are finite and trying to establish the programme on top of my other role, which is in triage, I only have very limited PT time.”

Implementation process

“Engaging Innovation Deliverers” was a strong facilitator for PTs and PwOA. Participants believed that attracting participation from appropriate healthcare professionals (HCPs) is important for implementation. They described several activities that may promote engagement including education, training, research, data, social marketing and role modelling.

PT 3: “You could use the argument with managers that you are clearing this cohort off the list and providing them with a service, which is easy to continue.”

PwOA 2: “I think the first phone call would be the consultant.”

“Teaming”, “Assessing Context”, “Engaging Innovation Recipients” and “Reflecting and Evaluating on the Implementation” were strong facilitators only for PwOA. They perceived that building a good support network with other participants was important for continued engagement. Also, the proximity of the class to their location, self-management education and supervision were positive influences on participation. Attracting participation from other PwOA to the programme is important, with participants suggesting word-of-mouth, role modelling, education and peer-to-peer rapport building strategies. Participants also believed that formal assessments to capture outcomes may improve programme implementation.

PwOA 2: “If it was known in the different hospitals that do orthopaedic surgery to give people the option of participating in that, I think more people might take it up.”

Discussion

Consistent with previous research, our findings within the CFIR domains of “Innovation”, “Outer Setting”, “Inner Setting”, “Individuals” and “Implementation Process” highlighted how characteristics and preferences of stakeholders and healthcare settings affect implementation. New healthcare services that are guideline-based and supported by colleagues/management are positively associated with implementation [26]. Gleadhill et al. [27] found that integration was crucial, with 77% of PTs (n = 57) rating their colleague’s treatment choices as ‘important’ or ‘very important’. This indicates the importance of developing appropriate care pathways and partnerships between stakeholders and healthcare settings. Participant-reported recommendations to encourage participation included early access to training and knowledge on components and benefits of the programme, social/role modelling, peer-to-peer marketing/word-of-mouth, and targeted education on up-to-date guidelines. Likewise, Parmar et al. [26] found that developing multidisciplinary teams, brainstorming potential implementation challenges and solutions, assigning responsibilities, and promoting HCP buy-in are critical steps to “intentional implementation planning”. Moreover, collecting feedback on implementation outcomes as an indicator of programme effectiveness may be used to improve stakeholder buy-in [28].

The use of new healthcare services is further promoted if participants perceive that programme marketing and training materials are easily accessible, and modifiable to meet specific needs [29]. Our participants believed that the programme may be tailored to suit their needs citing examples such as flexibility to use alternative equipment and the option to refine exercises to fit the home/outdoor environment. Also, the development of alternative online-delivered exercise and education self-management programmes may alleviate limitations imposed by work/caring responsibilities, location, or symptoms [30]. Further, training on how to implement the programme, and perceived confidence in capabilities to effectively execute the required steps are important positive determinants [26, 31]. Similar to GLA:D trained PTs in Switzerland (n = 86) who reported limited time and lack of appropriate space in the healthcare setting [32], our participants emphasised the need for flexible training opportunities that may improve participation (e.g., fit clinical time, proximity of training centre). Interestingly, PwOA did not report a lack of appropriate space (physical/technical features) as an implementation barrier citing opposing experiences to PTs. Possible reasons for this contrast in our findings could be due to differences in participant healthcare settings; the majority of PwOA in our sample reported as “private” healthcare settings (55.6%, n = 5), whereas majority of PTs reported “public” (80.0%, n = 8). Ireland’s private system offers faster access to and better choice of providers/services for those who can afford voluntary health insurance or to pay out of pocket [12]. While the Irish Health Service Executive delivers direct and indirect services, access to public healthcare remains poor. Specifically, Irish PwOA are estimated to use healthcare services significantly more than those without OA, costing €13.6 million annually [33]. Notably, only PTs reported the availability of internal and external funding/grants or reimbursement models as important determinants of implementation success. They perceived that the availability of financial support to implement new healthcare services is limited, citing that long-term adoption of new programmes may be difficult. A systematic review of reviews also reported that the financial climate of healthcare settings (e.g., allocation of or grants from health authorities/government funds) affects the implementation of evidence-based guidelines and new responsibilities [34]. It is pertinent to note that PTs in private healthcare settings did not identify financial climate as an implementation barrier. This supports previous findings on inequities in healthcare financing between public and private healthcare settings [13, 35]. Due to such inequities, it is possible participants in private healthcare settings are less likely to have experienced setting-level barriers to guideline-based clinical practice. Advocating for improved access to grants and reimbursement models and the development of programme guidelines/toolkits for logistics and financing may be effective. Likewise, future implementation efforts may find it helpful to define the necessary components of exercise and education self-management programmes for OA allowing healthcare settings to adapt services as relevant to their contexts.

Also, participation in GLA:D Ireland was perceived to be more beneficial than current clinical practice. While the perceived relative advantage of new healthcare services is an important factor in implementation success [36], it may be further compounded by dissatisfaction with current clinical practices. For example, challenges within healthcare settings are a barrier to implementation and may promote relative priority for testing new guideline-based programmes that aid global efforts to strengthen healthcare settings [7]. Additionally, implementation success may be influenced by how well the programme meets the needs of participants and is aligned with their beliefs/expectations. HCPs who were strongly interested in prevention also perceived a chronic disease prevention and screening programme to be a good fit with their role [37]. Similarly, in the implementation evaluation study on GLA:D Australia, PTs (n = 1064) reported that addressing participant beliefs about OA and treatment options was key to improving programme reach [18]. Our participants also described how PTs and healthcare settings addressed their needs including, receiving coaching/supervision, treatment choice and low costs. In the cross-cultural adaptation study on GLA:D Canada, PTs (n = 58) also described operational processes that may be patient-centred including, flexibility to schedule sessions and encouraging self-efficacy [17]. Future strategies may focus on promoting PwOA exercise behaviours and providing self-management education for stakeholders that highlights the benefits and advantages of exercise and education self-management programmes for OA.

Implications

Findings provide more specific knowledge on multilevel (programme, stakeholder and healthcare setting) implementation determinants of guideline-based healthcare services for OA. This comprehensive insight may guide research, policy, and practice towards the development of new healthcare strategies that are effective. Specifically, the identification of more strong implementation facilitators than barriers indicates that stakeholders and healthcare settings may acknowledge the importance of implementing guideline-based programmes for OA. It also suggests that future implementers must focus on addressing strong implementation barriers including, lack of time, unclear roles/responsibilities, limited internal and external financial support, and inappropriate space (physical and/or technical features). Further work on targeted strategies to address strong implementation determinants across varying geographical locations, healthcare settings, and stakeholders is needed. For example, a targeted strategy for a new healthcare service in the future may recommend an implementation checklist that requires implementers to develop multidisciplinary teams with designated responsibilities and/or to secure dedicated space/funding prior to the onset of the programme. Additionally, our findings on commonalities and differences between stakeholders (PTs vs PwOA) and healthcare settings (public vs private) may help provide evidence of the gap in the provision of guideline-based OA management. This is critical for supporting global priorities to shift healthcare policies and alleviate the OA burden. Specifically, future work must focus on advocating for equitable staffing levels, funding, and space to implement new guideline-based healthcare services. Also, our participants were offered GLA:D Ireland at no financial cost, and more work on the impact of limited public healthcare funding and out-of-pocket private healthcare costs on healthcare service utilisation is needed.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is its focus on the combination of theoretical framework-based and explorative approaches to interpret the experiences of PTs and PwOA. Using CFIR allowed for both a context-specific (rating each construct for each participant) and variable-oriented (rating each construct across all participants) approach to identifying implementation barriers and facilitators [38]. Additionally, using the updated CFIR framework based on user feedback [20] ensured that a broad range of outcomes were examined to identify what works where and why, and our definitions/approach to operationalisation may help establish and strengthen validated measures, relationships, and boundaries within CFIR. Further, reflexive assessment of reviewers’ beliefs/experiences helped counteract potential bias. The study sample was mostly female, older age, reported knee pain and were evenly located in public and private healthcare settings [39, 40]. Although reasons for non-response to interview requests were unclear, perhaps time constraints or lack of interest to continue participation may have contributed. While the robustness of the research approaches adds credence to the findings, at individual healthcare setting levels, the findings of this study must be contextualised in maximising generalisability.

Conclusion

To alleviate the public health burden of OA, global efforts to strengthen healthcare service delivery must address implementation barriers and facilitators of new guideline-based healthcare services. This study qualitatively identified the implementation determinants of PTs and PwOA for a supervised group neuromuscular exercise and education self-management programme for OA in public and private healthcare settings. Implementation may be strengthened by tailored training and education for stakeholders on the components and benefits of the programme, with more guidance needed for public healthcare settings on organising (e.g., scheduling clinic time, assigning responsibilities), planning (e.g., securing appropriate space, marketing/training tools), and funding (e.g., accessing dedicated internal/external grants). Future healthcare policy and practice may benefit from a framework-based approach to evaluating implementation determinants that may be applicable across broad contexts. Such contextualised research-driven strategies may support the future development of guideline-based healthcare services that encourage access to high-quality, equitable healthcare.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) from Zenodo at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10473852.

References

Steinmetz JD, Culbreth GT, Haile LM, Rafferty Q, Lo J et al (2023) Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990–2020 and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol 5(9):e508–e522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00163-7

Gray B, Eyles JP, Grace S, Hunter DJ, Østerås N et al (2022) Best evidence osteoarthritis care: what are the recommendations and what is needed to improve practice? Clin Geriatr Med 38(2):287–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2021.11.003

Conley B, Bunzli S, Bullen J, O’Brien P, Persaud J et al (2023) Core recommendations for osteoarthritis care: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Arthr Care Res (Hoboken) 75(9):1897–1907. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.25101

Hagen KB, Smedslund G, Østerås N, Jamtvedt G (2016) Quality of community-based osteoarthritis care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthr Care Res (Hoboken) 68(10):1443–1452. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22891

Baumann AA, Cabassa LJ (2020) Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Serv Res 20(1):190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4975-3

Cunningham J, Doyle F, Ryan JM, Clyne B, Cadogan C et al (2023) Primary care-based models of care for osteoarthritis; a scoping review. Semin Arthr Rheum 61:152221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2023.152221

Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health (2021) Towards a global strategy to improve musculoskeletal health. https://gmusc.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Final-report-with-metadata.pdf. Accessed 25 October, 2023

Skou ST, Roos EM (2017) Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:D™): evidence-based education and supervised neuromuscular exercise delivered by certified physiotherapists nationwide. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18(1):72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1439-y

Roos EM, Grønne DT, Skou ST, Zywiel MG, McGlasson R et al (2021) Immediate outcomes following the GLA:D® program in Denmark, Canada and Australia. A longitudinal analysis including 28,370 patients with symptomatic knee or hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil 29(4):502–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2020.12.024

Toomey CM, Kennedy N, MacFarlane A, Glynn L, Forbes J et al (2022) Implementation of clinical guidelines for osteoarthritis together (IMPACT): protocol for a participatory health research approach to implementing high value care. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 23(1):643. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05599-w

GLA:D Ireland (2022) GLA:D Annual Report 2022. https://www.gladireland.ie/gla-d-ireland-annual-reports. Accessed 25 October, 2023

Burke S, Barry S, Siersbaek R, Johnston B, Ní Fhallúin M et al (2018) Sláintecare – A ten-year plan to achieve universal healthcare in Ireland. Health Policy 122(12):1278–1282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.05.006

Murphy A, Bourke J, Turner B (2020) A two-tiered public-private health system: Who stays in (private) hospitals in Ireland? Health Policy 124(7):765–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.04.003

Kelleher D, Barry L, McGowan B, Doherty E, Carey JJ et al (2020) Budget impact analysis of an early identification and referral model for diagnosing patients with suspected rheumatoid arthritis in Ireland. Rheumatol Adv Pract 4(2):rkaa059. https://doi.org/10.1093/rap/rkaa059

Bauer MS, Kirchner J (2020) Implementation science: what is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Res 283:112376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.025

Bosse G, Breuer JP, Spies C (2006) The resistance to changing guidelines–what are the challenges and how to meet them. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 20(3):379–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2006.02.005

Davis AM, Kennedy D, Wong R, Robarts S, Skou ST et al (2018) Cross-cultural adaptation and implementation of Good Life with osteoarthritis in Denmark (GLA:D™): group education and exercise for hip and knee osteoarthritis is feasible in Canada. Osteoarthrit Cartil 26(2):211–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2017.11.005

Barton CJ, Kemp JL, Roos EM, Skou ST, Dundules K et al (2021) Program evaluation of GLA:D® Australia: Physiotherapist training outcomes and effectiveness of implementation for people with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthrit Cartil Open 3(3):100175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2021.100175

Gaglio B, Shoup JA, Glasgow RE (2013) The RE-AIM framework: a systematic review of use over time. Am J Public Health 103(6):e38–e46. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301299

Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, Lowery J (2022) The updated consolidated framework for implementation research based on user feedback. Implement Sci 17(1):75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0

Warner G, Lawson B, Sampalli T, Burge F, Gibson R et al (2018) Applying the consolidated framework for implementation research to identify barriers affecting implementation of an online frailty tool into primary health care: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 18(1):395. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3163-1

Wang H, Zhang Y, Yue S (2023) Exploring barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of home rehabilitation care for older adults with disabilities using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). BMC Geriatr 23(1):292. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03976-1

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9):1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (2023) Qualitative Data. https://cfirguide.org/evaluation-design/qualitative-data/. Accessed 14 March 2023

Damschroder LJ, Lowery JC (2013) Evaluation of a large-scale weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implement Sci 8(1):51. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-51

Parmar J, Sacrey LA, Anderson S, Charles L, Dobbs B et al (2022) Facilitators, barriers and considerations for the implementation of healthcare innovation: a qualitative rapid systematic review. Health Soc Care Community 30(3):856–868. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13578

Gleadhill C, Bolsewicz K, Davidson SRE, Kamper SJ, Tutty A et al (2022) Physiotherapists’ opinions, barriers, and enablers to providing evidence-based care: a mixed-methods study. BMC Health Serv Res 22(1):1382. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08741-5

Rogers LQ, Goncalves L, Martin MY, Pisu M, Smith TL et al (2019) Beyond efficacy: a qualitative organizational perspective on key implementation science constructs important to physical activity intervention translation to rural community cancer care sites. J Cancer Surviv 13(4):537–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00773-x

Cardona MI, Monsees J, Schmachtenberg T, Grünewald A, Thyrian JR (2023) Implementing a physical activity project for people with dementia in Germany-Identification of barriers and facilitator using consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR): a qualitative study. PLoS One 18(8):e0289737. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0289737

Turolla A, Rossettini G, Viceconti A, Palese A, Geri T (2020) Musculoskeletal physical therapy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: is telerehabilitation the answer? Phys Ther 100(8):1260–1264. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzaa093

MacKay C, Hawker GA, Jaglal SB (2018) Qualitative study exploring the factors influencing physical therapy management of early knee osteoarthritis in Canada. BMJ Open 8(11):e023457. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023457

Hinteregger A, Niedermann K, Wirz M (2023) The feasibility, facilitators, and barriers in the initial implementation phase of ‘good life with osteoarthritis in Denmark’ (GLA:D®) in Switzerland: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res 23(1):1034. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10023-7

Doherty E, O’Neill C (2014) Estimating the health-care usage associated with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in an older adult population in Ireland. J Public Health (Oxf) 36(3):504–510. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdt097

Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, Dziedzic K, Treweek S et al (2016) Achieving change in primary care–causes of the evidence to practice gap: systematic reviews of reviews. Implement Sci 11:40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0396-4

Smith S, Normand C (2009) Analysing equity in health care financing: a flow of funds approach. Soc Sci Med 69(3):379–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.030

Lewis CC, Mettert K, Lyon AR (2021) Determining the influence of intervention characteristics on implementation success requires reliable and valid measures: results from a systematic review. Implement Res Pract. https://doi.org/10.1177/2633489521994197

Sopcak N, Aguilar C, O’Brien MA, Nykiforuk C, Aubrey-Bassler K et al (2016) Implementation of the BETTER 2 program: a qualitative study exploring barriers and facilitators of a novel way to improve chronic disease prevention and screening in primary care. Implement Sci 11(1):158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0525-0

Miles MB, Huberman AM (1994) Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Eighan J, Walsh B, Smith S, Wren M-A, Barron S et al (2019) A profile of physiotherapy supply in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 188(1):19–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-018-1806-1

French HP, Galvin R, Horgan NF, Kenny RA (2016) Prevalence and burden of osteoarthritis amongst older people in Ireland: findings from The Irish LongituDinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Eur J Public Health 26(1):192–198. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv109

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (2023) Ùpdated CFIR Constructs. https://cfirguide.org/constructs/. Accessed 27 October, 2023

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium. Open access funding supported by the Health Research Board Emerging Investigator Award (EIA-2019-008) awarded to CMT and AB. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bhardwaj A: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft Preparation; FitzGerald C: Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing; Graham M: Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing; MacFarlane A: Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing; Kennedy N: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing; Toomey CM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

No conflicts of interests were disclosed.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Limerick Faculty of Education & Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (REC) (2020_12_13_EHS), Galway Clinical REC (C.A.2685), National Orthopaedic Hospital Cappagh REC (NOHC-2022-ETH-MB-CEO-331), Clinical REC of the Cork Teaching Hospitals (ECM 4 (v) 16/11/2021 & ECM 3 (cc) 22/02/2022), and the University of Limerick Hospitals Group Mid-West Region REC (051/2022).

Congress abstract publication

Data from the current study will be presented at one scientific meeting. Bhardwaj, A., FitzGerald, C., Graham, M., MacFarlane, A., Kennedy, N. and Toomey, CM. (in press). ‘Barriers and Facilitators to Implementation of an Exercise and Education Programme for Osteoarthritis: A Qualitative Study Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.’ Osteoarthr Cartil.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhardwaj, A., FitzGerald, C., Graham, M. et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of an exercise and education programme for osteoarthritis: a qualitative study using the consolidated framework for implementation research. Rheumatol Int 44, 1035–1050 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-024-05590-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-024-05590-9