Abstract

Suboptimal fibromyalgia management with over-the-counter analgesics leads to deteriorated outcomes for pain and mental health symptoms especially in low-income countries hosting refugees. To examine the association between the over-the-counter analgesics and the severity of fibromyalgia, depression, anxiety and PTSD symptoms in a cohort of Syrian refugees. This is a cross-sectional study. Fibromyalgia was assessed using the patient self-report survey for the assessment of fibromyalgia. Depression was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, insomnia severity was measured using the insomnia severity index (ISI-A), and PTSD was assessed using the Davidson trauma scale (DTS)-DSM-IV. Data were analyzed from 291. Among them, 221 (75.9%) reported using acetaminophen, 79 (27.1%) reported using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and 56 (19.2%) reported receiving a prescription for centrally acting medications (CAMs). Fibromyalgia screening was significantly associated with using NSAIDs (OR 3.03, 95% CI 1.58–5.80, p = 0.001). Severe depression was significantly associated with using NSAIDs (OR 2.07, 95% CI 2.18–3.81, p = 0.02) and CAMs (OR 2.74, 95% CI 1.30–5.76, p = 0.008). Severe insomnia was significantly associated with the use of CAMs (OR 3.90, 95% CI 2.04–5.61, p < 0.001). PTSD symptoms were associated with the use of CAMs (β = 8.99, p = 0.001) and NSAIDs (β = 10.39, p < 0.001). Improper analgesics are associated with poor fibromyalgia and mental health outcomes, prompt awareness efforts are required to address this challenge for the refugees and health care providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Migration resulting from war displacement has become a growing global challenge, with the number of international refugees reaching unprecedented levels [1]. Among traumatized refugees, chronic pain is frequently reported, contributing to a detrimental cycle of poor mental health symptoms and low quality of life [2, 3], and is part of a vicious cycle of poor mental health symptoms and low quality of life [4].

Fibromyalgia, a condition characterized by widespread pain accompanied by mood and sleep disturbances, is prevalent in approximately 5% of the general population and affects around 30% of war-displaced Syrian refugees, with a higher incidence in women [5,6,7].

Fibromyalgia significantly impairs daily functioning and social activities in women and is closely associated with poor mental health status. A substantial proportion of fibromyalgia patients also experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with approximately one in every two patients reporting clinically significant PTSD and insomnia [4, 8]. Depression and anxiety disorders are also commonly observed, affecting 40% of individuals diagnosed with fibromyalgia [9].

The management of fibromyalgia is multifaceted and holistic, encompassing psychotherapy, physiotherapy, and pharmacotherapy [10]. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines recommend the use of centrally acting medications (CAMs), including anti-seizure medications and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, as they have shown efficacy in fibromyalgia treatment [11]. However, due to a lack of awareness about fibromyalgia, over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics such as acetaminophen (APAP) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly utilized [7]. In addition, individuals may resort to various household pain remedies, such as herbal preparations or warm compresses, to alleviate the widespread pain associated with fibromyalgia [12].

Proper diagnosis, management, and long-term care for women with fibromyalgia require specialized expertise, laboratory tests, medications, psychotherapy, social support, physiotherapy, and other interventions. Unfortunately, these resources are often unavailable or overlooked, particularly in war-displaced refugee communities where priority is given to addressing basic medical needs [13]. As a result, the majority of Syrian women tend to rely on conventional analgesics to manage their symptoms [12]. However, the potential impact of using these analgesics on fibromyalgia symptoms and related mental health outcomes remains largely unknown.

To the best of our knowledge, limited data exist regarding the potential association between analgesics such as APAP, NSAIDs, CAM, and the symptoms of fibromyalgia, depression, insomnia, and PTSD in vulnerable female refugees. Therefore, the objective of this study is to examine the association between OTC analgesics and the severity of subjective fibromyalgia, depression, insomnia, and PTSD symptoms in a cohort of war-displaced female Syrian refugees residing in Jordan.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional cohort study using predefined inclusion criteria. It followed a similar design as in previous cross-sectional cohort studies [14,15,16].

Patients

The study recruited female Syrian refugees through the utilization of data sets from Caritas, a Catholic Non-governmental organization, which operates medical and social care centers in Jordan.

Inclusion criteria

Females, aged above 18 years old, frequenting Caritas Primary Social and Health Care Centers, living in urban districts, displaced for 5 years or more, non-smoking, unemployed, willing to participate, and have completed the study questionnaire were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Females, aged below 18 years old, displaced in Jordan for less than 5 years, employed, smoking, unwilling to participate, and not completing the study questionnaire were excluded from the study.

Main outcome variables

Fibromyalgia

To screen for fibromyalgia symptoms among the refugees, the Patient Self-Report Survey for Fibromyalgia Assessment was employed. Diagnosing fibromyalgia accurately is challenging, particularly in low-income settings in primary care centers serving a high number of refugees where the care is focused on controlling infectious diseases and non-communicable chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes [13, 17]. Therefore, the authors opted to use the aforementioned scale, which comprises the Widespread Pain Index (a body map depicting 19 potential tender points) and Symptom Severity. Based on the 2011 modification of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia, individuals who reported experiencing symptoms at a similar level for at least 3 months, with a score equal to or greater than 13 points (7 or higher points on the widespread pain scale and 5 or more on the severity scale and symptoms that persist for 3 months) and the absence of a medical condition explaining the symptoms, were deemed to have fibromyalgia [18]. This approach was further informed by previous research that examined the prevalence of fibromyalgia using questionnaire-based methods [14,15,16].

PTSD

To assess the severity of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among participants, the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) [19] based on DSM-IV criteria was employed. The Arabic version of the DTS, used by Ali et al. [20], was utilized. This 17-item self-report measure evaluates the 17 symptoms of PTSD outlined in the DSM-IV. Each item is rated on a 5-point frequency scale (ranging from 0 for "not at all" to 4 for "every day") and a severity scale (ranging from 0 for "not at all distressing" to 4 for "extremely distressing"). Scores on the DTS range from 0 to 68, with higher scores indicating more severe PTSD symptoms.

Depression

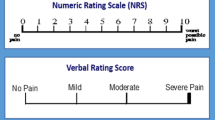

Depression severity was assessed using the Arabic-validated version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which aligns with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV criteria for diagnosing depressive symptoms [21]. The PHQ-9 has demonstrated a sensitivity and specificity of 88% for severe depression. It measures depression symptoms over the past 2 weeks and yields a score between 0 and 27, with a cutoff score of > 14 indicating severe depression [22,23,24].

Insomnia

The Arabic version of the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI-A) was used to evaluate sleep quality. Developed by [25], the ISI consists of 7 Likert-type questions, and its score ranges from 0 to 28. A cutoff score of > 14 indicates severe insomnia symptoms. The ISI has been validated for use in the Arabic language [26]

Study factors

Covariates

A self-administered structured online questionnaire was employed, consisting of various sections. Participants provided information on their age, marital status, residence location, body mass index, presence of chronic diseases namely hypertension and diabetes, and utilization of over-the-counter analgesics or centrally-acting prescribed medications for pain related to fibromyalgia symptoms.

Exposure

To ensure accurate data regarding analgesics used, the questionnaire incorporated brand and generic names, as well as pictures, of analgesics dispensed in Caritas pharmacies. This encompassed acetaminophen (APAP), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and centrally acting medications (CAMs) such as anti-seizure medications or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (e.g., duloxetine), depending on availability in the Caritas pharmacy unit. Additionally, two additional options were included: hot water compresses and herbal homemade remedies like anise, fennel, and green tea used in households.

Procedures

A well-trained female research assistant contacted potential participants via phone calls to provide detailed explanations regarding the study's objectives and methods. Interested individuals were then sent a study link that directed the participants to the Google survey to participate in the study.

The first page of the study instrument consisted of the informed consent form, where participants were required to read the objective and the methods of the study and then choose either to (“Yes: I agree to participate” or “No: I don’t agree to participate”). The study instrument was prepared in Arabic language. It is important to note that participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. The study received approval from the Yarmouk University IRB committee (number 175/2023) dated in 30/5/2023].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, means, and standard deviations, were utilized to summarize sample characteristics. Multivariate binary logistic regression models were employed to examine the association between different analgesics and mental health outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia. For PTSD, a multivariate linear regression model was employed to assess PTSD severity, preceded by an independent t test to examine the association between analgesic groups and PTSD severity, as the scale used did not establish a cutoff score. Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square analysis, and variables with a p value < 0.10 were included in the multivariate regression models. Finally, multivariable regression models were performed to identify independent associations between exposure variables and outcome variables (dependent variables). A statistical significance level of p < 0.05 (two-sided) was set, and estimates were provided with a 95% confidence interval.

Results

Response rate

Out of the 1100 eligible participants approached over the phone, 543 phone numbers were disconnected, 219 declined participations, and 47 were excluded due to incomplete data. Therefore, a total of 291 participants were included for analysis, resulting in a response rate of 26.5%.

Participants characteristics

Among the 291 participants, 151 (51.9%) were aged above 35 years old, 232 (79.7%) were married, and 169 (58.1%) resided outside Amman. Regarding analgesic use, 221 (75.9%) reported using acetaminophen, 106 (36.4%) reported using household herbal remedies, 79 (27.1%) reported using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), 42 (14.4%) reported using hot compresses, 56 (19.2%) reported receiving a prescription of centrally acting medications (CAMs), and 24 (8.2%) reported using no analgesics. Moreover, 169 (58.1%) reported a score consistent with fibromyalgia symptoms, 170 (58.4%) reported a score consistent with severe depressive symptoms, 159 (54.6%) reported a score consistent with severe insomnia symptoms, and the mean score for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was 30.57 (± 18.06). Please refer to Table 1 for detailed information.

Association between analgesic classes and the participants’ factors

A Chi-square analysis revealed significant associations between analgesic groups and various categorical participant variables. Specifically, the use of acetaminophen was associated with education level and the diagnosis of chronic diseases (p < 0.05). NSAID use was associated with age, body mass index (BMI), severity of fibromyalgia symptoms, severity of insomnia symptoms, and severity of depressive symptoms (p < 0.05). The use of hot compresses was associated with age, education level, BMI, diagnosis of chronic diseases, severity of fibromyalgia symptoms, severity of insomnia symptoms, and severity of depressive symptoms (p < 0.05). Similarly, the use of CAMs was associated with age, residence, BMI, severity of fibromyalgia symptoms, severity of insomnia symptoms, and severity of depressive symptoms (p < 0.05). Additionally, an independent t-test analysis indicated no significant difference in PTSD scores between acetaminophen users (30.71 ± 18.10) and non-users (30.12 ± 18.07), t(287) = − 0.24, p = 0.81. However, users of NSAIDs reported significantly higher PTSD scores (39.40 ± 15.93) compared to non-users (27.30 ± 17.70), t(287) = − 5.29, p < 0.001. Similarly, users of hot compresses reported significantly higher PTSD scores (36.00 ± 20.04) compared to non-users (29.62 ± 17.57), t(287) = − 2.17, p = 0.03. Users of herbal household remedies showed slightly higher PTSD scores (32.18 ± 18.01) compared to non-users (29.63 ± 18.07), although the difference was not statistically significant, t(287) = − 1.16, p = 0.25. However, participants receiving a prescription of CAMs reported significantly higher PTSD scores (39.84 ± 16.37) compared to non-users (28.34 ± 17.78), t(287) = − 4.41, p < 0.001. Please refer to Table 2 for detailed results.

Multivariate analysis

Multivariate binary logistic regression models were employed to assess the association between analgesic use and various mental health outcomes. For severe depressive symptoms, the final model included age, chronic diseases, NSAIDs, and CAMs. Only NSAIDs (2.07, 95% CI [2.18–3.81], p = 0.02) and CAMs (2.74, 95% CI [1.30–5.76], p = 0.008) demonstrated a significant association, indicating that participants using NSAIDs and CAMs had increased odds of experiencing severe depressive symptoms.

Regarding fibromyalgia symptoms, the final multivariate binary logistic regression model included age, chronic diseases, and NSAIDs. NSAIDs (3.03, 95% CI [1.58–5.80], p = 0.001), chronic diseases (2.48, 95% CI [1.36–4.53], p < 0.001), and age above 35 years (2.09, 95% CI [1.17–3.73], p = 0.006) exhibited significant associations, indicating that NSAID users, participants diagnosed with chronic diseases, and participants older than 35 years had higher odds of experiencing fibromyalgia symptoms.

For severe insomnia, the final multivariate binary logistic regression model included age, chronic diseases, NSAIDs, and CAMs. Only CAMs (3.90, 95% CI [2.04–5.61], p < 0.001) demonstrated a significant association, indicating that participants receiving CAMs had higher odds of experiencing severe insomnia.

Lastly, the multivariate linear regression model for PTSD included age, chronic diseases, hot compresses, NSAIDs, and CAMs. In the final model, both CAMs (β = 8.99, p = 0.001) and NSAIDs (β = 10.39, p < 0.001) showed significant associations with PTSD, suggesting that users of NSAIDs and CAMs were more likely to have higher PTSD scores. Please refer to Table 3 for detailed results.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the association between OTC analgesics and the severity of subjective fibromyalgia, depression, insomnia, and PTSD symptoms in a cohort of war-displaced female Syrian refugees.

We report a high prevalence of fibromyalgia, depression, anxiety, and insomnia in our study sample. The use of NSAIDs was associated with fibromyalgia symptoms. In addition, we report that NSAIDs and CAMs were associated with severe depression, severe insomnia symptoms, and severe PTSD symptoms. The use of APAP was not associated with any of the outcome variables.

War-displaced traumatized refugees experience chronic psychological stress that starts from the moment of displacement and continues after migration and settlement [27]. This stress accompanied by neuroendocrine alterations is a leading predisposing factor to developing many physical and mental disorders such as fibromyalgia and other related mental disturbances [28]. Furthermore, the awareness of the health care providers about fibromyalgia is limited, therefore, the majority of the subjects rely on OTC analgesics for symptomatic management. This explains the high rates of fibromyalgia in this study in comparison to normal displaced populations [7].

Fibromyalgia, a central pain syndrome is best managed by antiepileptic or antidepressants according to the ACR guidelines [29].

In the present study, the majority of the participants utilized APAP. This finding is consistent with our previous results, which indicated APAP as the most commonly used medication for pain [7, 12]. This could reflect the role of healthcare providers in directing patients towards APAP, as it is relatively safer with fewer contraindications. APAP may also be chosen due to its availability or lower price [30, 31]. The present study revealed no association between APAP and fibromyalgia or other mental health symptoms, which is consistent with our previous work where APAP was not associated with PTSD among Syrian refugee females [12].

The use of NSAIDs was associated with more severe depression, insomnia, PTSD, and fibromyalgia symptoms in our study sample. NSAIDs exert their analgesic and anti-inflammatory actions by peripherally inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX), the enzyme responsible for prostaglandin synthesis, which makes NSAIDs superior to APAP in alleviating peripheral pain [32]. In the current study, vulnerable females suffering from fibromyalgia symptoms also reported poor mental health outcomes. Therefore, our findings can be explained by the fact that females with severe fibromyalgia and poor mental health symptoms were more likely to use NSAIDs as a more effective option compared to APAP for relieving chronic widespread pain symptoms [33, 34]. Our previous study also showed that the use of NSAIDs is associated with poor fibromyalgia and mental health outcomes [7].

The ACR guidelines recommend the use of CAMs, such as anti-seizure medications or antidepressants, in the treatment of fibromyalgia [18, 35]. In our study, the use of CAMs was associated with severe depression, insomnia, and PTSD, but not with fibromyalgia. The term "CAM" refers to a prescription of centrally acting or "neurological medication for pain," as explained by the participants. This indicates the use of antiseizure or SNRI medications dispensed from the Caritas pharmacy unit. Approximately 19% of our study sample used CAMs, and their use was not associated with severe fibromyalgia symptoms. This finding is consistent with the ACR guidelines. It represents an improvement in healthcare quality compared to previous studies where only 1% of the same study population reported receiving a prescription for CAM for fibromyalgia [7]. Fibromyalgia in refugees is closely related to depression, insomnia, and PTSD [4]. Users of CAMs may have been diagnosed with fibromyalgia and may also be experiencing mental distress [4, 9]. This could explain the association between CAM use and severe depression, insomnia, and PTSD, suggesting that CAMs may alleviate fibromyalgia symptoms but no other related symptoms.

Our work adds to the existing literature on the impact of analgesics on fibromyalgia and mental health outcomes in war-displaced female refugees. The novelty of the idea, unique sample recruitment, inclusion criteria, and use of validated scales were strengths in the study design. However, the study has some limitations. The self-completing questionnaire may lack accuracy, especially for fibromyalgia. Proper diagnosis of fibromyalgia is challenging and costly, which is particularly true in low-income countries hosting war refugees. However, the self-reported scales were previously used to screen fibromyalgia and provide guidance [14,15,16]. In this study Based on the 2011 modification of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia, individuals who reported experiencing symptoms at a similar level for at least 3 months, with a score equal to or greater than 13 points (7 or higher points on the widespread pain scale and 5 or more on the severity scale and symptoms that persist for 3 months) and the absence of a medical condition explaining the symptoms, were positively screened for fibromyalgia.

Another limitation was the low response rate of the participants, which may reflect the challenges of maintaining an updated database and the dynamic nature of refugees' social circumstances, including changes in residence and phone numbers. Furthermore, complete medical profiles and detailed information regarding the NSAIDs and CAMs, such as exact names and doses, were challenging to obtain from the refugees, as they may seek medical help from different NGOs, resulting in fragmented medical records.

Conclusion

The use of suboptimal fibromyalgia treatments is associated with poor fibromyalgia, depression, anxiety, insomnia, and PTSD self-reported symptoms in female refugees. Therefore, efforts are required to raise awareness among patients and healthcare providers regarding the proper management of fibromyalgia among this vulnerable group.

Data availability

For inquiries related to data access, please contact the corresponding author's email.

References

Altun A, Brown H, Sturgiss L, Russell G (2022) Evaluating chronic pain interventions in recent refugees and immigrant populations: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 105:1152–1169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.08.021

Teodorescu D-S, Heir T, Siqveland J et al (2015) Chronic pain in multi-traumatized outpatients with a refugee background resettled in Norway: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol 3:1–12

Buhmann CB (2014) Traumatized refugees: morbidity, treatment and predictors of outcome. Dan Med J 61:B4871

Al-Smadi AM, Tawalbeh LI, Gammoh OS et al (2021) Relationship between anxiety, post-traumatic stress, insomnia and fibromyalgia among female refugees in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 28:738–747

Mease P (2005) Fibromyalgia syndrome: review of clinical presentation, pathogenesis, outcome measures, and treatment. J Rheumatol Suppl 75:6–21

McCarthy J (2016) Myalgias and myopathies: fibromyalgia. FP Essent 440:11–15

Gammoh OS, Al-Smadi A, Tayfur M et al (2020) Syrian female war refugees: preliminary fibromyalgia and insomnia screening and treatment trends. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 24:387–391

Cohen H, Neumann L, Haiman Y et al (2002) Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in fibromyalgia patients: Overlapping syndromes or post-traumatic fibromyalgia syndrome? Semin Arthritis Rheum 32:38–50. https://doi.org/10.1053/sarh.2002.33719

Gracely RH, Ceko M, Bushnell MC (2012) Fibromyalgia and depression. Pain Res Treat. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/486590

Binkiewicz-Glińska A, Bakuła S, Tomczak H et al (2015) Fibromyalgia Syndrome-a multidisciplinary approach. Psychiatr Pol 49:801–810

Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB et al (1990) The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum Off J Am Coll Rheumatol 33:160–172

Gammoh O, Durand H, Abu-Shaikh H, Alsous M (2023) Post-traumatic stress disorder burden among female Syrian war refugees is associated with dysmenorrhea severity but not with the analgesics. Electron J Gen Med 20:em485. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejgm/13089

Gammoh OS (2016) A preliminary description of medical complaints and medication consumption among 375 Syrian refugees residing in North Jordan. Jordan J Pharm Sci 9:13–21

Samman AA, Bokhari RA, Idris S et al (2021) The prevalence of fibromyalgia among medical students at King Abdulaziz University: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.12670

Branco JC, Bannwarth B, Failde I, Carbonell JA, Blotman F, Spaeth M, Saraiva F, Nacci F, Thomas E, Caubère JP, Le Lay K (2010) Prevalence of fibromyalgia: a survey in five European countries. In: Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism, vol 39, No. 6. WB Saunders, pp 448–453

Patel A, Al-Saffar A, Sharma M et al (2021) Prevalence of fibromyalgia in medical students and its association with lifestyle factors—a cross-sectional study. Reumatologia/Rheumatology 59:138–145

Gammoh O, Bjørk M-H, Al Rob OA et al (2023) The association between antihypertensive medications and mental health outcomes among Syrian war refugees with stress and hypertension. J Psychosom Res 168:111200

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M-A et al (2011) Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 38:1113–1122

Davidson JRT, Book SW, Colket JT et al (1997) Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med 27:153–160

Ali M, Farooq N, Bhatti MA, Kuroiwa C (2012) Assessment of prevalence and determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of earthquake in Pakistan using Davidson Trauma Scale. J Affect Disord 136:238–243

Patrick S, Connick P (2019) Psychometric properties of the PHQ-9 depression scale in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. PLoS One 14:e0197943

AlHadi AN, AlAteeq DA, Al-Sharif E et al (2017) An arabic translation, reliability, and validation of Patient Health Questionnaire in a Saudi sample. Ann Gen Psychiatry 16:1–9

Aljishi RH, Almatrafi RJ, Alzayer ZA et al (2021) Prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with multiple sclerosis in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.20792

Costantini L, Pasquarella C, Odone A et al (2020) Screening for depression in primary care with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): a systematic review. J Affect Disord. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.131

Morin C (1993) Insomnia: psychological assessment and management

Suleiman KH, Yates BC (2011) Translating the insomnia severity index into Arabic. J Nurs Scholarsh 43:49–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01374.x

Gammouh O, Al-Smadi A (2015) LT-P chronic, 2015 undefined Peer reviewed: Chronic diseases, lack of medications, and depression among Syrian refugees in Jordan, 2013–2014. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Carta MG, Moro MF, Pinna FL et al (2018) The impact of fibromyalgia syndrome and the role of comorbidity with mood and post-traumatic stress disorder in worsening the quality of life. Int J Soc Psychiatry 64:647–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764018795211

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA et al (2010) The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res 62:600–610. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20140

Power DV, Pratt RJ (2012) Karen refugees from Burma: focus group analysis. Int J Migr Heal Soc Care 8:156–166

Towheed T, Maxwell L, Judd M et al (2006) Acetaminophen for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd004257.pub2

Zeng AM, Nami NF, Wu CL, Murphy JD (2016) The analgesic efficacy of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) in patients undergoing cesarean deliveries: a meta-analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med 41:763–772. https://doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0000000000000460

Wattier JM (2018) Conventional analgesics and non-pharmacological multidisciplinary therapeutic treatment in endometriosis: CNGOF-HAS Endometriosis Guidelines. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol 46:248–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gofs.2018.02.002

Hang X, Zhang Y, Li J et al (2021) Comparative efficacy and acceptability of anti-inflammatory agents on major depressive disorder: a network meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol 12:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.691200

Häuser W, Wolfe F, Tölle T et al (2012) The role of antidepressants in the management of fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs 26:297–307

Acknowledgements

The corresponding author would like to thank Prof. Guiseppe Moscati, Suzan, Yasmina, and Nour for their support.

Funding

The study was funded by Yarmouk University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; (OG, AA, MT). Drafting the work or reviewing it critically for important intellectual content; (OG, AA, MT). Final approval of the version to be published; (OG, AA, MT). Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved (all authors).

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The study received approval from the Yarmouk University IRB committee (number 175/2023) dated in 31/5/2023.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gammoh, O., Aljabali, A.A.A. & Tambuwala, M.M. The crosstalk between subjective fibromyalgia, mental health symptoms and the use of over-the-counter analgesics in female Syrian refugees: a cross-sectional web-based study. Rheumatol Int 44, 715–723 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-023-05521-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-023-05521-0