Abstract

To assess the reporting quality of interventions aiming at promoting physical activity (PA) using a wearable activity tracker (WAT) in patients with inflammatory arthritis (IA) or hip/knee osteoarthritis (OA). A systematic search was performed in eight databases (including PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library) for studies published between 2000 and 2022. Two reviewers independently selected studies and extracted data on study characteristics and the reporting of the PA intervention using a WAT using the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) (12 items) and Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) E-Health checklist (16 items). The reporting quality of each study was expressed as a percentage of reported items of the total CERT and CONSORT E-Health (50% or less = poor; 51–79% = moderate; and 80–100% = good reporting quality). Sixteen studies were included; three involved patients with IA and 13 with OA. Reporting quality was poor in 6/16 studies and moderate in 10/16 studies, according to the CERT and poor in 8/16 and moderate in 8/16 studies following the CONSORT E-Health checklist. Poorly reported checklist items included: the description of decision rule(s) for determining progression and the starting level, the number of adverse events and how adherence or fidelity was assessed. In clinical trials on PA interventions using a WAT in patients with IA or OA, the reporting quality of delivery process is moderate to poor. The poor reporting quality of the progression and tailoring of the PA programs makes replication difficult. Improvements in reporting quality are necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

People with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) are at greater risk of physical inactivity compared with their healthy peers, as they are often limited by disabling health problems and encounter disease specific barriers to be physically active [1, 2]. Promotion of physical activity (PA) and exercise are key components in clinical practice guidelines for the management of people with RMDs [3,4,5], based on the favorable effects of PA on pain, disease activity, joint range of motion, aerobic capacity, muscle strength and overall functional ability [6,7,8,9,10,11]. In addition, patients with an RMD may gain from the general health benefits and from the reduction of the increased risk of cardiovascular disease associated with inflammatory RMDs [12].

A frequently used strategy to promote PA in adults with chronic diseases includes monitoring and feedback of PA [13], which can be supported by the use of wearable activity trackers (WATs). WATs to stimulate PA can range from pedometers to advanced WATs that can provide real-time feedback (i.e. Fitbit® or Garmin® watches). Several systematic literature reviews have shown that PA promotion with the use of WATs has a moderate, positive effect on PA levels in patients with various (chronic) diseases, including RMDs, compared to the control intervention without a WAT or with usual care [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. A general conclusion from these reviews concerned the heterogeneity of the description of the interventions, whereas in one review the overall insufficient quality of reporting on the interventions was specifically addressed [16]. Using a WAT for PA promotion usually includes additional interventions, such as instruction on how to use the WAT and any digital applications or patient education, including behavioral change techniques such as individual goal setting. The variability and lack of information on these topics hamper the replication of studies for future research and the interpretation of the effects for, e.g. clinical guidelines. The reporting quality on WAT delivery in studies of PA promotion in patients with RMDs has not yet been systematically evaluated.

The reporting quality of trials with PA interventions using a WAT should preferably meet the requirements as defined in checklists for the reporting of PA interventions and of eHealth interventions [21,22,23,24]. Regarding PA or exercise interventions, there are various checklists available, including the Standard Protocol Items Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT statement) [21], the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR checklist) [23] and the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT checklist) [24]. The latter has been widely applied to assess the quality of PA intervention descriptions in low back pain, hip osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia and juvenile idiopathic arthritis populations [25,26,27,28]. The CONSORT E-Health checklist is generally mentioned as a reporting tool for web-based and mobile health interventions [22].

To date, no study has systematically assessed the reporting quality of intervention strategies that used a WAT as part of PA promotion in RMDs. Therefore, the aim of this study is to provide an overview of the reporting quality of interventions promoting PA using a WAT in patients with inflammatory arthritis (IA) or osteoarthritis (OA), using the CERT and CONSORT E-Health reporting checklists.

Methods

A systematic search was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement [29]. This review was performed based on a prespecified study protocol that was registered in the international Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42021213408).

Search strategy

The search was confined to studies published from 1st of January 2000 onwards, as the use of WATs was not common before that time. The final search was performed on June 27th 2022. The search strategy was developed by a trained librarian (JWS) and included MeSH terms and free text (see Online Resource 1 for complete PubMed search strategy). The following databases were used: PubMed, Embase (OVID), Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Emcare (OVID), PsycINFO (EbscoHOST), Academic Search Premier (EbscoHOST) and PEDro. Records were identified, imported to a reference list in EndNote™ version 20 [30] and subsequently into a reference system Rayyan (http://rayyan.qcri.org) [31] after removal of duplicates. No additional search for ongoing studies or unpublished data was done. The titles and abstracts of systematic reviews obtained from the search were also screened for potentially eligible studies.

Eligibility criteria, participants and type of intervention

The selection of the studies was based on following criteria: Inclusion criteria: studies (i) published between 1st of January 2000 and June 27th 2022; (ii) written in English or Dutch; (iii) including patients older than 18 years; (iv) with inflammatory arthritis (i.e. axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), or juvenile arthritis (JIA)) or hip or knee OA (including those scheduled for or underwent total hip or total knee arthroplasty (THA or TKA)) and mixed populations of patients with RMDs; (v) describing interventions aiming to increase PA and including the use of a WAT for that purpose; a WAT was defined as an electronic device designed to be worn on the user’s body; including accelerometers, altimeters, or other sensors to track the wearer’s movements and/or biometric data; (vi) with one of the following designs: observational studies (including pilot studies, pre-post studies or case series (at least ten subjects)), experimental studies including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi randomized controlled trials, controlled clinical trials, cluster randomized controlled trials and cross-over studies; (vii) availability of the full-text of the paper.

Exclusion criteria: studies (i) describing interventions using a way of self-monitoring of PA other than a WAT; (ii) a conference abstract, research letter or commentarial note or any other type of publication not being report of a clinical study.

Study selection

Study selection was performed by two reviewers (MVW and MB) independently in two steps: first, titles and abstracts were screened and full-text papers were retrieved for studies potentially meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Second, the full-text papers were assessed using the same eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers and if agreement was not reached, a third and fourth reviewer were consulted (SVW and TVV). The titles and abstracts of systematic reviews obtained from the search were also screened. All articles included in the selected systematic reviews were checked against the same eligibility criteria, first for abstract and title, then full-text. This process was documented in a Microsoft Excel [32] screening data file, in which an overview of the eligibility criteria was provided for each screened record.

Data extraction

Data extraction of the included studies was done by one reviewer (MVW) and verified by the second reviewer (MB). Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers and if agreement was not reached a third and fourth reviewer were consulted (SVW and TVV). The following data were extracted on a pre-designed data extraction form:

General characteristics

First author, country, year of publication, study design, in- and exclusion criteria, number and characteristics of subjects (mean age (years), gender (female/male) and diagnosis).

Reporting quality of the WAT and related interventions

To assess the quality of reporting on the delivery of the WAT and concurrent strategies, the CERT and CONSORT E-Health checklist were applied. Some items of the CERT and CONSORT E-Health checklist overlap. Similarities between CERT and CONSORT E-Health items are shown in Online Resource 2.

The CERT checklist is an extension of the TIDieR checklist [23], with the aim of providing authors direction for reporting exercise interventions by including key items that are considered essential for replicating. The CERT checklist comprises 16 items listed under seven categories: what (materials); who (provider); how (delivery); where (location); when and how much (dosage); tailoring (what, how); and how well (compliance/planned and actual). The CONSORT E-Health checklist is a detailed sub-checklist as an extension to the CONSORT item 5 intervention statement [33]. It comprises 12 items, listing required and desired reporting elements characterizing the functional components and other important features of the E-Health interventions.

Data were extracted for all CERT en CONSORT E-Health items and scored ‘1’ (adequately reported) or ‘0’ (not adequately reported or unclear).

Risk of bias assessment

Methodological quality assessment of RCTs was based on a risk of bias (RoB) assessment performed by two independent reviewers (XXX and XX). Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion and if agreement was not reached a third and fourth reviewer were consulted (XXX or XXX). The RoB 2 tool developed by the Cochrane Collaboration [34] was used for RCTs and ROBINS-I (the Risk Of Bias In Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions) was used for the non-randomized observational studies [35].

The RoB 2 tool comprises five domains, focusing on randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome and selection of the reported results. The ROBINS-I includes seven domains, focusing on confounding, selection of participants into the study, classification on interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurements of outcomes and selection of the reported results.

For both the RoB 2 and ROBINS-I tool, the judgement of the risk of bias are calculated by the individual scores of the domains, based on answers to the signaling questions. The response options of the signaling questions are: “Yes”; “Probably yes”; “Probably no”; “No”; and “No information”. Some signaling questions are only answered if the response to a previous signaling question is “Yes” or “Probably yes” (or “No” or “Probably no”). Judgment of the overall risk of bias can be low, some concern or high, with a low risk corresponding to a high-quality trial.

Statistical analyses and synthesis

A descriptive analysis was used to assess the reporting quality. For each study, each item of the CERT and CONSORT E-Health is scored with ‘1’ (adequately reported) or ‘0’ (not adequately reported or unclear). The reporting quality of each individual study is based on the percentage of adequately reported items of the 16 items for the CERT and 12 items for the CONSORT E-Health, respectively. Based on this percentage, the overall quality of reporting is classified into poor (50% or less), moderate (51 to 79%) or good (80–100%), as described by Mercieca-Bebber et al. [36]. The reporting quality of the individual items for the CERT and CONSORT E-Health is also calculated. The reporting quality of each item was calculated by dividing the number of studies that adequately reported the item by the total number of studies included. Thus, these results are expressed as the percentage of studies reporting a specific item.

Results

Selection of studies

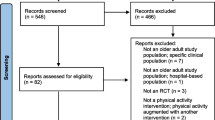

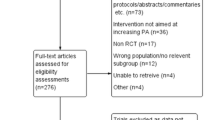

After removing duplicates, the search yielded 2.137 records, of which 124 were systematic reviews. Titles and abstracts of the 2.013 non-systematic reviews were screened from which 31 records were selected for screening of the full text papers, with 14 of these meeting the eligibility criteria. Of the 124 systematic reviews, eight were considered relevant to the research question, and included 111 clinical studies. After removing duplicates or not meeting the eligibility criteria, six of those papers were selected for full-text review resulting in the inclusion of three articles. So, in total 17 articles, describing 16 studies, met the eligibility criteria and were included in this review (Fig. 1: Flow diagram of selected studies).

General characteristics of included studies and populations

General characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. The 16 studies included a total of 858 participants across seven countries (United States, Canada, Sweden, France, Jordan, Japan and Australia). Ten studies included patients with knee OA, hip OA or OA (not specified), with a mean age of the participants ranging from 40 to 74 years [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Three studies included patients who underwent an unilateral TKR or TKA, participants included in these studies had a mean age ranging from 60 to 68 years [48,49,50]. The other three studies included patients with RA [51], spondyloarthritis [52] and RA or Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) [53] with a mean age of 55 years [51], 52 years [52] and 55 years [53], respectively. All but three of 16 studies were RCTs [41, 44, 47]. The exceptions concerned a pre–post-study without a control group [47] and the other two were feasibility studies including two intervention groups [41, 44]. Four of the RCTs had a controlled delay group [38,39,40, 53] and the other nine studies a parallel control group. The duration of interventions ranged from 1 week to 6 months. In the 13 studies with a control group, the control group received education (n = 2) [50, 51], usual care (n = 1) [50], monthly or weekly phone calls to discuss overall health (n = 2) [48, 50], physical therapy/activity (n = 4) [37, 48, 49, 52], newsletter/email about their disease (n = 2) [38, 53], theoretical group session with information on OA (n = 1) [43], individual appointment with a physical therapist for specific exercises based on needs and goals (n = 1) [43], and/or a blinded WAT (n = 1) [45].

Characteristics of the WAT

Detailed description on the type and brand of equipment (WAT) was reported in 14 of 16 studies (88%). Nine studies used the Fitbit®, with some variation regarding the type. In five of the studies a Fitbit Flex® was used [38,39,40, 43, 53], in three studies the Fitbit Zip® [48, 50, 51] and in one study the FitBit Charge 2® [47]. It was reported that the Fitbit Zip® was worn around the waist [48], whereas the Fitbit Flex (2)® and Fitbit Charge 2® were worn around the wrist [38,39,40, 43, 47]. Three of these nine studies did not explain the location of wearing of the Fitbit Flex or Zip® [50, 51, 53]. Two studies used a Garmin Vivofit 4.0®, worn around the wrist [44, 52]. Three other studies used an electronic pedometer as WAT (Jawbone UP 24® [45] worn around the waist, KenzLifecoder EX® worn around the wrist [37] and Omron HJ-320® [49] location of wearing unknown). Two studies did not report the type and brand of the WAT at all [41, 46]. Characteristic of the WATs are described in Online Resource 3.

Determining the starting level and tailoring of the use of a WAT in the PA program

Description of a decision rule to determine the starting level at which people start the PA program with a WAT was reported in 31% of the studies (5/16 studies) [37, 45,46,47, 51]. The starting level of the (step) goal in these five studies was based on the average daily steps of the first week. The other 11 studies did not describe any information on the starting level. Description of the PA programs/exercises and if they were generic or tailored are described in all but one of the studies (94%) [49], but a detailed description of how exercise were tailored to the individual was only described by 25% of the studies (4/16 studies) [47, 50, 51, 53]. Seven of the 16 studies (44%) described how the progression of the PA program was executed [37, 41, 46,47,48, 50, 51]; however, the decision rule(s) for determining exercise progression was only described by 13% of the studies (2/16 studies) [47, 50]. Details are also described in Online Resource 3.

Non-exercise components or motivational strategies in PA programs

All but one of the studies reported non-exercise components or motivational strategies [49]. In six of the 16 studies instructions on the use of the WAT was included [43,44,45, 47, 48, 50]. Another non-exercise component was the information and/or education given about PA and/or self-management of the disease. This information/education was given in group sessions by nine of the 16 studies [38,39,40, 43, 46, 50,51,52,53] and/or in newsletters, guides or booklets by six of the 16 studies [41, 44,45,46, 50, 51]. Motivational strategies were also included in ten of the 16 studies, including personal counseling in PA goals. In seven of those ten studies, weekly or bi-weekly phone calls were made to monitor and/or recall the PA goals [38,39,40, 43, 46, 47, 53], three studies did this by text messages [45, 47, 52]. Details on the non-exercise components and motivational strategies given during the PA intervention are stated in Online Resource 4.

Adherence, fidelity and adverse events

In nine of the 16 studies, the measurement of adherence to the intervention was described [38, 39, 43, 45, 46, 48, 50, 51, 53]. The adherence measured by attendance to education sessions [38, 46, 53], use of the WAT [38, 39, 43, 46, 48, 50, 51, 53], and participation in PA goal counselling sessions [38, 53]. Of the 16 included studies, seven studies reported information about the type and number of adverse events [38,39,40, 45, 48, 51, 53]. Details on the adherence, fidelity and adverse events are stated in Online Resource 5.

Risk of bias assessment

Full consensus was reached between researchers MB and MVW on risk of bias assessment. Overall, the methodological quality of the included trails was moderate to good. Six of the sixteen studies had a low [37, 38, 43, 45, 46, 53] and ten studie had a moderate risk of bias [39,40,41, 44, 47,48,49,50,51,52], whereas the studies from Paxton et al. and Darabseh et al. had the highest risk of bias [49, 50]. The randomization process was not clearly described in three of the studies [49,50,51]. Also, the selection of the reported results were not clearly described for four of the studies [40, 48, 49, 52]. Details are described in Online Resources 6 and 7.

Statistical analyses and synthesis

None of the studies had a complete reporting of the process of delivery of interventions using WATs to increase PA in patients with RMDs. For all studies the reporting quality was poor to moderate, according to both the CERT and CONSORT E-Health checklists. According to the CERT checklist, the reporting quality was classified as poor for six of the 16 studies [37, 43,44,45, 49, 52] and moderate for the other ten studies [38,39,40,41, 46,47,48, 50, 51, 53]. Of the ten studies with moderate reporting quality, the two studies with the highest quality had reported 68% of the items adequately [47, 48], the other eight studies showed lower percentages [38,39,40,41, 46, 50, 51, 53].

According to the CONSORT E-Health checklist the reporting quality was classified as poor for eight studies [37, 41, 45,46,47, 49,50,51], and the other eight of the 16 studies had a moderate reporting quality [38,39,40, 43, 44, 48, 52, 53]. All eight moderate reporting quality studies scored 58% of the items adequately. An overview of the reporting quality of the studies is shown in Table 2.

Of the CERT checklist, two of the 19 items were not reported in any of the studies (i.e. description of each exercise to enable replication and any home program components) and 8 of the 19 items were only reported by 50% or less of the studies (i.e. description of: the decision rule(s) for determining exercise progression; how the exercise program was progressed; the type and number of adverse events that occur during exercise; the exercise intervention including, but not limited to, number of exercise repetitions/sets/sessions, session duration, program duration; how exercises are tailored to the individual; the decision rule for determining the starting level at which people start an exercise program; how adherence or fidelity is assessed/measured; the extent to which the intervention was delivered as planned). Four of the 19 CERT items were reported by 51–79% of the studies (i.e. description of: the qualifications, expertise and/or training undertaken by the exercise instructor; motivational strategies; of how adherence to exercise is measured and reported; exercises are performed individually or in a group), and five of the 19 items were reported in more than 80% of the studies (i.e. description of: the type of exercise equipment; whether the exercises are generic (one size fits all) or tailored; exercises are supervised or unsupervised, how they are delivered; the setting in which the exercises are performed; whether there are any non-exercise components). In total five of the 12 CONSORT E-Health checklist items were not reported by any of the studies; description of the history and development process, revisions and updating, quality assurance methods and digital preservation. Two items of the CONSORT E-Health checklist were reported in 51–79% of the studies (i.e. description of the level of human involvement and any prompts/reminders used) and five items were reported in 80% or more of the studies (i.e. description of: developers/owners; access; mode of delivery of the intervention; use parameters and any co-interventions). An overview of the reporting quality of the checklist items are also shown in Table 2.

There was only limited overlap between the studies with poor reporting quality and those with a high risk of bias. Of the ten studies with a moderate risk of bias, three also showed poor reporting quality on the CERT checklist [47, 49, 52] and four [41, 49,50,51] on the CONSORT E-Health checklist.

Discussion

In this systematic review on the reporting quality of interventions to increase PA in patients with RMDs using WATs, it was found that overall the reporting quality was moderate to poor. Based on two checklists, for the reporting of exercise interventions (CERT) and eHealth interventions (CONSORT E-Health), the best reported items concerned the description of the equipment, supervision of the intervention and whether there were any non-exercise components included in the intervention. On the other hand, information on the description of the starting level, decision rules and progression of exercises, the description and tailoring of the exercises, adverse events, fidelity of the intervention, revisions and update of WATs and accessory quality assurance methods were in general not or poorly reported and are points of improvement for future studies.

Moderate to poor reporting quality of interventions targeting PA appears to be a more common problem. A previous systematic review on the effect of WATs on levels of PA in patients with various (chronic) diseases including RMDs concluded that the description of the interventions was heterogenous [16]. To date, no studies have systematically assessed the reporting quality of PA interventions including a WAT in patients with RMDs. Recently published systematic reviews on the reporting quality of PA promotion concern interventions without the use of a WAT in patients with low back pain [26], hip OA [25], pulmonary hypertension [54], progressive supranuclear palsy [55] and JIA [28] are in line with the results of our study, and concluded that the reporting quality of PA promotion interventions (all using the CERT checklist) was generally moderate to low. However, the findings on specific CERT items that were not or poorly reported were mixed and sometimes even contradictory. In addition, there is only one systematic review on the reporting quality of digital interventions using the CONSORT E-Health checklist, regarding digital interventions in general, in patients with cardiometabolic conditions [56]. That review used eight of the CONSORT E-Health items, and also concluded an overall inconsistent reporting of the interventions. Their finding regarding insufficient reporting of the development process is in line with the results of our study. Moreover, the results of previous studies and our study underline the need to develop better guidelines for the reporting of interventions targeting PA using WATs.

Complete reporting may have been limited due to lack of requirements from journals for authors to use the appropriate reporting guidelines, or journal restrictions on e.g. the length of a manuscript or number of tables. This was confirmed in a systematic review of Abell et al. where the completeness of reporting on exercise-based interventions increased from 8 to 43% after additional information was requested by corresponding authors [57]. In contrast to that study, no additional information was requested from authors within our systematic review. In case of incomplete reporting of specific elements, only the available study protocols or websites were consulted. Thus, it cannot be ruled out that failure to consult the corresponding author may have led to an underestimation of the reporting quality of the included studies. The CERT [22] and CONSORT E-Health checklist [24] were already published in 2016 and 2011. All but three studies in this review [37, 41, 46] were published after the checklists were available. The impact of these checklists on the reporting quality therefore appears to be limited.

A complicating factor in assessing the reporting quality of the delivery of WATs is the suitability of currently available sets of criteria for doing so. First of all, the CERT and CONSORT E-Health were designed as reporting guidelines and not as a measure to assess the reporting quality. To our knowledge, such reporting quality assessment instruments are not available. In this systematic review both reporting quality checklists were used, as both comprised elements that are relevant for the delivery of WATs to promote PA. Although there was some overlap regarding their contents, the description of items varied considerably, and both also comprised elements that were unique. Overall, neither of the checklists nor their combination appeared to be complete. As WATs are more and more used in PA promotion, the development of sets of criteria to report the delivery process of WATs and assess the reporting quality is needed. These sets could also consist of items already present in existing CERT and CONSORT E-Health checklists. While not within the scope of this systematic review, it would be interesting to assess the effect of the PA interventions using a WAT. However, no effects could be measured due to the heterogenous and moderate to poor reporting quality of the interventions. Future research, including more studies in RMD patients and with better reporting quality, should discuss the effect of PA interventions including a WAT in RMD patients.

This overview of reporting quality and the subsequent results may have implications for researchers and clinicians. For researchers, improvement of the reporting quality will increase the accurate application of WATs in clinical trials, make it easier to replicate studies and compare their results. Only when interventions are described in a comprehensive and standardized manner data from different studies can be analyzed and pooled. To improve the reporting quality, researchers may use the combination of the CERT [24] and CONSORT E-Health [22] checklists. However, the current systematic review demonstrated that the combination of both resulted in incomplete reporting of some aspects that are particularly relevant for WATs. Thus, the development of a specific guideline for reporting of interventions aimed at PA promotion with the use of a WAT is desired. For clinicians, improved reporting quality will increase the therapeutic validity of the interventions they are offering. Currently, the lack of relevant and/or detailed information hinders clinicians from implementing and carrying out the intervention as intended, because, e.g. information about determining the starting level and decision rules for progression or tailoring of PA using a WAT is lacking. Until now, clinicians may have to contact the corresponding authors for additional information on the methods used, which is not considered to be feasible for clinical practice.

A strength of the current study is the comprehensive evaluation of the reporting quality using two existing checklists and highlighting the key items for improvement in the reporting of interventions using WATs to increase PA. A systematic search was completed in most major databases, with a complementary hand search of systematic reviews to ensure that no relevant studies were missed. A limitation is that a larger number of studies would allow for sub-analysis of other characteristics of the studies, such as the publication journal and its author guidelines. Moreover, this systematic review included only three studies with patients with IA [51,52,53]. The observed difference between the number of identified studies on IA as compared to OA is likely to be related to the difference in the prevalence of OA and IA, with hip and knee OA being far more prevalent than IA. Likewise, the number of clinical trials on exercise and PA promotion is much more extensive in OA than in IA. Nevertheless, it is likely that the principles of the delivery of PA interventions with the use of a WAT are similar in OA and IA, and there is little ground for the expectation that the reporting quality of PA promotion interventions using a WAT would be different. So, although exceptions cannot be ruled out, it is likely that the conclusions of this review on the reporting quality are generalizable to studies on PA promotion for different RMDs. Regarding the practical approach to PA promotion in patients with different conditions, it is beyond doubt that this may differ at the individual patient level, in part due to differences in the clinical features of their underlying condition. However, the basic principles of exercise and PA promotion are similar, as is, e.g. reflected in the 2018 EULAR (European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology) recommendations for PA for people with IA and OA [58] that explicitly address both IA and OA together.

Conclusion

This study provides a first overview of the reporting quality of interventions using WATs to increase PA in patients with RMDs. While PA interventions using WATs have the potential to benefit people with RMDs [17], the moderate to poor reporting quality of PA interventions using WATs limits future replication and assessment of effects. The development of criteria to report on the use of WATs for PA promotion is needed and can improve the reporting quality and clinical usefulness of future studies.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sieper J, Poddubnyy D (2017) Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet 390(10089):73–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31591-4

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB (2016) Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 388(10055):2023–2038. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30173-8

Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, Towheed T, Welch V, Wells G, Tugwell P, American College of Rheumatology (2012) American college of rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 64(4):465–474. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21596

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians, Denberg TD, Barry MJ, Boyd C, Chow RD, Fitterman N, Harris RP, Humphrey LL, Vijan S (2017) Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American college of physicians. Ann Intern Med 166(7):514–530. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2367

Sepriano A, Regel A, van der Heijde D, Braun J, Baraliakos X, Landewe R, Van den Bosch F, Falzon L, Ramiro S (2017) Efficacy and safety of biological and targeted-synthetic DMARDs: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis. RMD Open 3(1):e000396. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2016-000396

Baillet A, Vaillant M, Guinot M, Juvin R, Gaudin P (2012) Efficacy of resistance exercises in rheumatoid arthritis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatology (Oxford) 51(3):519–527. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ker330

Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL (2015) Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Sports Med 49(24):1554–1557. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095424

Fransen M, McConnell S, Hernandez-Molina G, Reichenbach S (2014) Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007912.pub2

Rausch Osthoff AK, Juhl CB, Knittle K, Dagfinrud H, Hurkmans E, Braun J, Schoones J, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Niedermann K (2018) Effects of exercise and physical activity promotion: meta-analysis informing the 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis and hip/knee osteoarthritis. RMD Open 4(2):e000713. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000713

Regel A, Sepriano A, Baraliakos X, van der Heijde D, Braun J, Landewe R, Van den Bosch F, Falzon L, Ramiro S (2017) Efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological and non-biological pharmacological treatment: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis. RMD Open 3(1):e000397. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2016-000397

Smidt N, de Vet HCW, Bouter LM, Dekker J, Arendzen JH, de Bie RA, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Helders PJM, Keus SHJ, Kwakkel G, Lenssen T, Oostendorp RAB, Ostelo RWJG, Reijman M, Terwee CB, Theunissen C, Thomas S, van Baar ME, van’t Hul A, van Peppen RPS, Verhagen A, van der Windt DAWN, Exercise Therapy Group (2005) Effectiveness of exercise therapy: a best-evidence summary of systematic reviews. Aust J Physiother 51(2):71–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0004-9514(05)70036-2

Peters MJ, Symmons DP, McCarey D, Dijkmans BA, Nicola P, Kvien TK, McInnes IB, Haentzschel H, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Provan S, Semb A, Sidiropoulos P, Kitas G, Smulders YM, Soubrier M, Szekanecz Z, Sattar N, Nurmohamed MT (2010) EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 69(2):325–331. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2009.113696

Castro O, Ng K, Novoradovskaya E, Bosselut G, Hassandra M (2018) A scoping review on interventions to promote physical activity among adults with disabilities. Disabil Health J 11(2):174–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.10.013

Alothman S, Yahya A, Rucker J, Kluding PM (2017) Effectiveness of interventions for promoting objectively measured physical activity of adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. J Phys Act Health 14(5):408–415. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2016-0528

Baskerville R, Ricci-Cabello I, Roberts N, Farmer A (2017) Impact of accelerometer and pedometer use on physical activity and glycaemic control in people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med 34(5):612–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13331

Braakhuis HEM, Berger MAM, Bussmann JBJ (2019) Effectiveness of healthcare interventions using objective feedback on physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med 51(3):151–159. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2522

Davergne T, Pallot A, Dechartres A, Fautrel B, Gossec L (2019) Use of wearable activity trackers to improve physical activity behavior in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 71(6):758–767. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23752

de Vries HJ, Kooiman TJM, van Ittersum MW, van Brussel M, de Groot M (2016) Do activity monitors increase physical activity in adults with overweight or obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring) 24(10):2078–2091. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21619

Ridgers ND, McNarry MA, Mackintosh KA (2016) Feasibility and effectiveness of using wearable activity trackers in youth: a systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 4(4):e129. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.6540

Vaes AW, Cheung A, Atakhorrami M, Groenen MTJ, Amft O, Franssen FME, Wouters EFM, Spruit MA (2013) Effect of “activity monitor-based” counseling on physical activity and health-related outcomes in patients with chronic diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med 45(5–6):397–412. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890.2013.810891

Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, Laupacis A, Gotzsche PC, Krleza-Jeric K, Hrobjartsson A, Mann H, Dickersin K, Berlin JA, Dore CJ, Parulekar WR, Summerskill WSM, Groves T, Schulz KF, Sox HC, Rockhold FW, Rennie D, Moher D (2013) SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 158(3):200–207. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583

Eysenbach G, Group C-E (2011) CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res 13(4):e126. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1923

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman DG, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston M, Lamb SE, Dixon-Woods M, McCulloch P, Wyatt JC, Chan AW, Michie S (2014) Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 348:g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687

Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, Buchbinder R (2016) Consensus on exercise reporting template (CERT): explanation and elaboration statement. Br J Sports Med 50(23):1428–1437. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096651

Burgess LC, Wainwright TW, James KA, von Heideken J, Iversen MD (2021) The quality of intervention reporting in trials of therapeutic exercise for hip osteoarthritis: a secondary analysis of a systematic review. Trials 22(1):388. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05342-1

Davidson SRE, Kamper SJ, Haskins R, Robson E, Gleadhill C, da Silva PV, Williams A, Yu Z, Williams CM (2021) Exercise interventions for low back pain are poorly reported: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 139:279–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.05.020

Jo D, Del Bel MJ, McEwen D, O’Neil J, Mac Kiddie OS, Alvarez-Gallardo IC, Brosseau L (2019) A study of the description of exercise programs evaluated in randomized controlled trials involving people with fibromyalgia using different reporting tools, and validity of the tools related to pain relief. Clin Rehabil 33(3):557–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215518815931

Kattackal TR, Cavallo S, Brosseau L, Sivakumar A, Del Bel MJ, Dorion M, Ueffing E, Toupin-April K (2020) Assessing the reporting quality of physical activity programs in randomized controlled trials for the management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis using three standardized assessment tools. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 18(1):41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-020-00434-9

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group PRISMA (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med 3(3):e123-130

Team TE (2013) EndNote. EndNote, 20th edn. Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 5(1):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Microsoft Corporation (2019). Microsoft Excel. Retrieved from https://office.microsoft.com/excel

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, Elbourne D, Egger M, Altman DG (2010) CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340:c869. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c869

Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernan MA, Hopewell S, Hrobjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Juni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, Savovic J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR, Chan AW, Churchill R, Deeks JJ, Hrobjartsson A, Kirkham J, Juni P, Loke YK, Pigott TD, Ramsay CR, Regidor D, Rothstein HR, Sandhu L, Santaguida PL, Schunemann HJ, Shea B, Shrier I, Tugwell P, Turner L, Valentine JC, Waddington H, Waters E, Wells GA, Whiting PF, Higgins JP (2016) ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

Mercieca-Bebber R, Rouette J, Calvert M, King MT, McLeod L, Holch P, Palmer MJ, Brundage M, International Society for Quality of Life Research Best Practice for Reporting Taskforce (2017) Preliminary evidence on the uptake, use and benefits of the CONSORT-PRO extension. Qual Life Res 26(6):1427–1437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1508-6

Hiyama Y, Yamada M, Kitagawa A, Tei N, Okada S (2012) A four-week walking exercise programme in patients with knee osteoarthritis improves the ability of dual-task performance: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 26(5):403–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215511421028

Li LC, Feehan LM, Xie H, Lu N, Shaw CD, Gromala D, Zhu S, Avina-Zubieta JA, Hoens AM, Koehn C, Tam J, Therrien S, Townsend AF, Noonan G, Backman CL (2020) Effects of a 12-week multifaceted wearable-based program for people with knee osteoarthritis: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8(7):e19116. https://doi.org/10.2196/19116

Li LC, Sayre EC, Xie H, Clayton C, Feehan LM (2017) A community-based physical activity counselling program for people with knee osteoarthritis: feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the track-OA study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 5(6):e86. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.7863

Li LC, Sayre EC, Xie H, Falck RS, Best JR, Liu-Ambrose T, Grewal N, Hoens AM, Noonan G, Feehan LM (2018) Efficacy of a community-based technology-enabled physical activity counseling program for people with knee osteoarthritis: proof-of-concept study. J Med Internet Res 20(4):e159. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8514

Ng NT, Heesch KC, Brown WJ (2010) Efficacy of a progressive walking program and glucosamine sulphate supplementation on osteoarthritic symptoms of the hip and knee: a feasibility trial. Arthritis Res Ther 12(1):R25. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2932

Ostlind E, Eek F, Stigmar K, Sant’Anna A, Hansson EE (2022) Promoting work ability with a wearable activity tracker in working age individuals with hip and/or knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 23(1):112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05041-1

Ostlind E, Sant’Anna A, Eek F, Stigmar K, Ekvall Hansson E (2021) Physical activity patterns, adherence to using a wearable activity tracker during a 12-week period and correlation between self-reported function and physical activity in working age individuals with hip and/or knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22(1):450. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04338-x

Plumb Vilardaga JC, Kelleher SA, Diachina A, Riley J, Somers TJ (2022) Linking physical activity to personal values: feasibility and acceptability randomized pilot of a behavioral intervention for older adults with osteoarthritis pain. Pilot Feasibility Stud 8(1):164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-022-01121-0

Skrepnik N, Spitzer A, Altman R, Hoekstra J, Stewart J, Toselli R (2017) Assessing the impact of a novel smartphone application compared with standard follow-up on mobility of patients with knee osteoarthritis following treatment with Hylan G-F 20: a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 5(5):e64. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.7179

Talbot LA, Gaines JM, Huynh TN, Metter EJ (2003) A home-based pedometer-driven walking program to increase physical activity in older adults with osteoarthritis of the knee: a preliminary study. J Am Geriatr Soc 51(3):387–392. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51113.x

Zaslavsky O, Thompson HJ, McCurry SM, Landis CA, Kitsiou S, Ward TM, Heitkemper MM, Demiris G (2019) Use of a wearable technology and motivational interviews to improve sleep in older adults with osteoarthritis and sleep disturbance: a pilot study. Res Gerontol Nurs 12(4):167–173. https://doi.org/10.3928/19404921-20190319-02

Christiansen MB, Thoma LM, Master H, Voinier D, Schmitt LA, Ziegler ML, LaValley MP, White DK (2020) Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a physical therapist-administered physical activity intervention after total knee replacement. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 72(5):661–668. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23882

Darabseh MZRM, Darwish F (2017) The effects of pedometer-based intervention on patients after total knee replacement surgeries. Int J Rehabil Sci 6(1):17–24. https://doi.org/10.5455/ijhrs.0000000118

Paxton RJ, Forster JE, Miller MJ, Gerron KL, Stevens-Lapsley JE, Christiansen CL (2018) A feasibility study for improved physical activity after total knee arthroplasty. J Aging Phys Act 26(1):7–13. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2016-0268

Katz P, Margaretten M, Gregorich S, Trupin L (2018) Physical activity to reduce fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 70(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23230

Labat G, Hayotte M, Bailly L, Fabre R, Brocq O, Gerus P, Breuil V, Fournier-Mehouas M, Zory R, D’Arripe-Longueville F, Roux CH (2022) Impact of a wearable activity tracker on disease flares in spondyloarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.220140

Li LC, Feehan LM, Xie H, Lu N, Shaw C, Gromala D, Avina-Zubieta JA, Koehn C, Hoens AM, English K, Tam J, Therrien S, Townsend AF, Noonan G, Backman CL (2020) Efficacy of a physical activity counseling program with use of a wearable tracker in people with inflammatory arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 72(12):1755–1765. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24199

McGregor G, Powell R, Finnegan S, Nichols S, Underwood M (2018) Exercise rehabilitation programmes for pulmonary hypertension: a systematic review of intervention components and reporting quality. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 4(1):e000400. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000400

Slade SC, Underwood M, McGinley JL, Morris ME (2019) Exercise and progressive supranuclear palsy: the need for explicit exercise reporting. BMC Neurol 19(1):305. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1539-4

O’Neil A, Cocker F, Rarau P, Baptista S, Cassimatis M, Barr Taylor C, Lau AYS, Kanuri N, Oldenburg B (2017) Using digital interventions to improve the cardiometabolic health of populations: a meta-review of reporting quality. J Am Med Inform Assoc 24(4):867–879. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocw166

Abell B, Glasziou P, Hoffmann T (2015) Reporting and replicating trials of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation: do we know what the researchers actually did? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 8(2):187–194. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001381

Rausch Osthoff AK, Niedermann K, Braun J, Adams J, Brodin N, Dagfinrud H, Duruoz T, Esbensen BA, Günther KP, Hurkmans E, Juhl CB, Kennedy N, Kiltz U, Knittle K, Nurmohamed M, Pais S, Severijns G, Swinnen TW, Pitsillidou IA, Warburton L, Yankov Z, Vliet Vlieland TPM (2018) 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 77(9):1251–1260. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213585

Funding

This work was supported by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development [ZonMw; L-EXSPA: 852004019]; Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport [VWS]; the Dutch Arthritis Society [ReumaNederland] and the scientific college of the Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy [WCF-KNGF].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work (TPMVV and SFEVW); and Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content (MATVW, MAMB, JWS, MGJG, CHMVDE, TPMVV, SFEVW); AND Final approval of the version to be published (MATVW, MAMB, JWS, MGJG, CHMVDE, TPMVV, SFEVW); and Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved (MATVW, MAMB, JWS, MGJG, CHMVDE, TPMVV, SFEVW).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M.A.T. van Wissen, M.A.M. Berger, J.W. Schoones, M.G.J. Gademan, C.H.M. van den Ende, T.P.M. Vliet Vlieland and S.F.E. van Weely declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Wissen, M.A.T., Berger, M.A.M., Schoones, J.W. et al. Reporting quality of interventions using a wearable activity tracker to improve physical activity in patients with inflammatory arthritis or osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int 43, 803–824 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05241-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05241-x