Abstract

Globally, increasing demand for rheumatology services has led to a greater reliance on non-physician healthcare professionals (HCPs), such as rheumatology nurse specialists, to deliver care as part of a multidisciplinary team. Across Africa and the Middle East (AfME), there remains a shortage of rheumatology HCPs, including rheumatology nurses, which presents a major challenge to the delivery of rheumatology services, and subsequently the treatment and management of conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA). To further explore the importance of nurse-led care (NLC) for patients with RA and create a set of proposed strategies for the implementation of NLC in the AfME region, we used a modified Delphi technique. A review of the global literature was conducted using the PubMed search engine, with the most relevant publications selected. The findings were summarized and presented to the author group, which was composed of representatives from different countries and HCP disciplines. The authors also drew on their knowledge of the wider literature to provide context. Overall, results suggest that NLC is associated with improved patient perceptions of RA care, and equivalent or superior clinical and cost outcomes versus physician-led care in RA disease management. Expert commentary provided by the authors gives insights into the challenges of implementing nurse-led RA care. We further report practical proposed strategies for the development and implementation of NLC for patients with RA, specifically in the AfME region. These proposed strategies aim to act as a foundation for the introduction and development of NLC programs across the AfME region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The global prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is estimated to be 0.24% and on the rise due to an aging population [1]. Although there are limited epidemiological data for Africa and the Middle East (AfME), the prevalence of RA in some AfME countries is as high as 2.54% [2,3,4,5,6,7].

A study by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) found that the global demand for rheumatology services outstripped the supply of rheumatologists, with this imbalance projected to increase dramatically by 2030 [8]. Utilizing more non-physician service providers, such as specialist nurses, as part of a nurse-led care (NLC) model, is one suggested strategy to meet the increasing need for rheumatologists [9]. The NLC model has been defined as one in which nurses practice an extended role, assuming their own patient caseloads and providing patient services, such as treatment and monitoring, education, psychosocial support, and referral [10]. Internationally, NLC models have been used successfully in other chronic diseases, such as diabetes [11, 12], cardiovascular disease [13,14,15], and cancer [16]. Within the field of rheumatology, there have been specialist nurses working as part of multidisciplinary teams for over three decades in some regions [17]. Notably, in recognition of the vital role nurses can play in rheumatology care, some guidelines recommend that patients with RA have access to a nurse throughout their disease [18].

Despite global advances in rheumatology treatment, the management of RA in AfME countries remains suboptimal [19, 20], with challenges, including delayed referrals, lack of access to biologic therapies, and insufficient standardized disease assessment measures being used in clinical practice [19]. Furthermore, the burden of RA is frequently underestimated in AfME countries due to the perception that more prevalent conditions in the region (such as malnutrition, HIV, or tuberculosis) have a greater socio-economic impact, meaning that RA is not viewed as a healthcare priority [19, 21].

A lack of specialized HCPs and certified rheumatology nurse specialists also presents a major challenge to RA disease management in the AfME region, particularly in rural areas [19, 22]. Moreover, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the current global shortage of nursing personnel will worsen in the AfME region by 2030 [23]. Based on the authors’ expert knowledge, the reasons for this shortage include the absence of rheumatology nurse postgraduate degrees, structured pathways for training, and career progression, including well-developed courses on advanced clinical practice, as well as a lack of understanding of training needs across the region and lack of awareness of the importance of the role of the RA nurse.

With this in mind, the objective of this literature review was to explore the importance of NLC for patients with RA in a global setting, and to combine this evidence with the authors’ expert knowledge to provide proposed strategies regarding the implementation of NLC for RA in the AfME region, specifically.

Materials and methods

Literature search strategy and findings

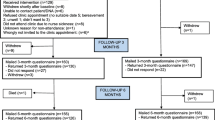

We used a modified Delphi technique to draft proposed strategies, following an extensive narrative literature review. Literature searches were conducted using PubMed, incorporating studies published between January 2008 and March 2018 based on the following search terms: (“nursing” OR “nurse”) AND “care” AND (“rheumatoid arthritis” OR “rheumatic disease”). A total of 296 papers were identified, and the titles manually reviewed for relevance; the screening process is outlined in Fig. 1. Papers selected for more detailed abstract review were limited to those written in English.

A total of 16 articles were identified as being most relevant and were reviewed (Table 1) [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Relevant articles were required to include adult patients (aged ≥ 16 years) with RA. One systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of NLC versus physician-led care (PLC), representing five randomized controlled trials (RCTs) subsequently considered for inclusion, was identified. These articles were predominantly in European settings, and most were conducted in specialized rheumatology clinics. All studies (aside from the meta-analysis) were set in a single country. The role of the nurses was varied and included coordinating treatment-to-target strategies, disease activity assessment, treatment modifications, patient education, and psychosocial support (Table 1). As detailed in Table 1, four key themes (patients’ perceptions of NLC in rheumatology, clinical effectiveness of NLC in rheumatology, impact of NLC on rheumatology healthcare costs and resource use, and training and resource needs identified by rheumatology nurse specialists) were identified from the articles; these themes are explored separately in the following narrative review of the literature.

The findings of the narrative review were summarized and presented to all authors. The author group comprised experts in rheumatology and nursing from different countries in the AfME region (Algeria, Jordan, Lebanon, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and UAE) and from the UK. Virtual open discussions were held between authors. All authors’ viewpoints and remarks were collected, summarized, and presented for further verification and adjustment. A consensus was developed by each author reviewing, adjusting, adding, deleting, combining, reforming, and approving proposed strategies. Each author participated in wording each proposed strategy.

Results

Patients’ perceptions of NLC in rheumatology

The literature search identified eight articles that explored the perceptions of NLC by patients with RA (Table 1).

As reported in interviews/surveys conducted with patients with RA in a Swedish rheumatology clinic, nurse-led management, information, and support was shown to be important in increasing patients’ sense of empowerment [26]. Nurses instilled feelings of security, trust, hope, and confidence [27, 36], and patients reported that they found it easier to discuss queries with nurses than with physicians [26]. Interestingly, in a 2016 study of the interactional style between patients and HCPs, patients with RA were seen to initiate more ‘personal talk’ and provide more unprompted information relevant to their care in nurse-led consultations, compared with physician-led consultations [38]. Therefore, it is unsurprising that the same study found nurses to engage in significantly more relationship building with their patients, compared with physicians [38]. In terms of the qualities that patients valued in their nurses, regular accessibility [26, 27, 36], competency in their disease and treatment knowledge [36], giving clear and meaningful explanations [27], and the provision of a patient-centered/holistic approach [26, 36] were mentioned consistently.

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs concerning the efficacy of, and patient satisfaction with, NLC had mixed results with respect to the latter: no significant differences in patient satisfaction with NLC versus PLC after a 1-year follow-up were reported (data from four RCTs) [28]. However, after a 2-year follow-up, significantly greater patient satisfaction was observed with NLC versus PLC (P < 0.05; data from two RCTs up to this time point) [28]. Specifically, one of these RCTs reported that patients with RA receiving NLC had significantly increased self-efficacy (defined as patients’ belief in their ability to perform specific tasks or behaviors to cope with their RA), confidence, and satisfaction at the 2-year follow-up versus patients receiving PLC [24]. Two studies in the meta-analysis used the Leeds Satisfaction Questionnaire (LSQ), a validated, self-administered questionnaire in which patients respond to a series of statements using a five-point Likert scale to assess their satisfaction levels across six subscales: general, information, empathy, technical, attitude, access [30, 34]. Results using this tool were mixed. Koksvik et al. reported significantly greater patient satisfaction across all subscales of the LSQ for patients with inflammatory arthritis (IA; RA, ankylosing spondylitis [AS], psoriatic arthritis [PsA], juvenile idiopathic arthritis [JIA], or undifferentiated polyarthritis) receiving NLC versus PLC at 9- and 21-month follow-up (primary endpoint; all P < 0.001, excepting general satisfaction at 9-month follow-up for which P < 0.05) [30]. However, in Ndosi et al., while general satisfaction scores were significantly higher with NLC versus PLC at 26-week follow-up (P < 0.05), no numerical differences in scores between patient groups were reported across the remaining LSQ subscales [34]. At 52-week follow-up, general satisfaction scores were similar to NLC versus PLC; as at the earlier time point, there were no numerical differences across the remaining LSQ subscales between patient groups [34].

Clinical effectiveness of NLC in rheumatology

The clinical effectiveness of NLC for patients in rheumatology care was evaluated in eight articles identified in the literature search (Table 1). A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs by de Thurah et al. reported no differences in disease activity data (per Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein [DAS28-4 [ESR/CRP]]) between NLC versus PLC at 1-year follow-up (data from four RCTs), and a statistically significant (P < 0.05), but not clinically relevant, the difference in disease activity favoring NLC at 2-year follow-up (data from two RCTs up to this time point) [28]. Of the two RCTs in the de Thurah et al. paper that reported disease activity at 1-year follow-up only, Ndosi et al. found that improvements in RA disease activity (primary endpoint; per DAS28) over 52 weeks for British patients receiving NLC were non-inferior to improvements for patients receiving PLC [34]. Similarly, a 12-month RCT in Sweden, as reported by Larsson et al. found that improvements in disease activity (primary endpoint; per DAS28-4 [ESR] and DAS28-4 [CRP]) were non-inferior in patients with stable chronic IA (CIA; RA, PsA, undifferentiated arthritis, or undifferentiated spondyloarthritis [SpA]) undergoing biologic therapy who had one of two annual rheumatologist monitoring visits replaced by a nurse-led monitoring visit, versus patients who saw a rheumatologist at both visits [31]. Of the two RCTs evaluated by de Thurah et al. that reported both 1- and 2-year disease activity data, Primdahl et al. reported no significant difference in disease activity (primary endpoint; per DAS28-4 [CRP]) in patients with RA receiving NLC versus PLC at 12 months, but found NLC to be significantly superior at 24 months (P = 0.049) [24]. Koksvik et al. found that improvements in disease activity (per DAS28-4 [ESR]) were significantly greater in patients with IA (RA, AS, PsA, JIA, or undifferentiated polyarthritis) receiving NLC versus PLC at 9-month follow-up (between-group difference in DAS28 [ESR] 0.45; P = 0.03), but no significant difference was seen at 21-month follow-up (between-group difference in DAS28 [ESR] 0.31; P = 0.15) [30].

Of the three further articles that explored the impact of NLC on disease activity (per DAS28), Muñoz-Fernández et al. found that there were no significant differences in RA disease activity with NLC versus PLC at 12-month follow-up (mean DAS28 of 2.7 vs. 2.8, respectively; P = 0.274) [33]. Similarly, across seven rheumatology practices in the US, no differences in changes in disease activity (per DAS28, Clinical Disease Activity Index [CDAI], and Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 score [RAPID3]) were observed between patients with RA treated by nurse practitioners or physician assistants versus those treated by rheumatologists only over 2 years [37]. However, a 12-month RCT conducted in China found that improvements in RA disease activity (per DAS28) were significantly greater in patients receiving NLC versus PLC throughout the study period (primary endpoint; P < 0.001) [39].

The impact of NLC on a range of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in patients with RA was explored in six studies, with mixed results [24, 30, 31, 33, 34, 39]. Wang et al. found that improvements in pain, fatigue, and stiffness were significantly greater with NLC versus PLC [39], while Muñoz-Fernández et al. reported significantly greater improvements in physical function and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) with NLC versus PLC [33]. In contrast, several studies reported no significant differences in improvements across PROs, including pain [24, 30, 31], physical function [24, 31], HRQoL [30], and fatigue [24, 30] in patients receiving NLC versus PLC. Finally, Ndosi et al. found that improvements in pain, physical function, fatigue, and stiffness in patients receiving NLC were non-inferior to improvements in patients receiving PLC [34].

Impact of NLC on rheumatology healthcare costs and resource use

The impact of NLC on rheumatology healthcare costs and resource use was assessed in five studies (Table 1). A 12-month RCT in Sweden of patients with stable CIA (RA, PsA, undifferentiated arthritis, or undifferentiated SpA) undergoing biologic therapy found that total annual rheumatology care costs per patient (including fixed monitoring, variable monitoring, rehabilitation, specialist consultations, radiography, and pharmacological therapy) were significantly lower for patients who had one of two annual rheumatologist monitoring visits replaced by a nurse-led monitoring visit versus patients who saw a rheumatologist at both visits (13% reduction in costs; P < 0.01) [32]. When annual resource use was investigated further, there were no significant differences between NLC and PLC for costs related to additional phone calls or visits to nurses/rheumatologists, rehabilitation, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, psychosocial treatment, specialist consulting, or radiography identified; while costs related to pharmacological therapy and additional blood tests were significantly higher with PLC versus NLC (P < 0.05) [32]. A 12-month RCT found that unplanned hospitalizations or additional clinic visits were less common in Chinese patients with stable RA receiving NLC versus PLC, with overall costs related to RA treatment, laboratory tests, radiography, steroid injections, and daycare admissions significantly lower with NLC versus PLC [39]. In addition to the reduced hospital visits observed with NLC, authors hypothesized that cost differences might also be due to the lower number of prescriptions, laboratory tests, and radiological investigations ordered for the NLC- versus PLC-recipient groups [39]. A 12-month RCT conducted in the UK also reported numerically lower rates of unplanned hospital admissions or visits to the accident and emergency department or general practitioner surgery with NLC versus PLC. However, differences in mean overall costs for RA care (including costs of clinic and specialist visits, community care, investigations, hospitalization, and medications) were not statistically significant between NLC and PLC groups, despite consultation costs for NLC being significantly lower versus PLC (P < 0.001) [34].

Similarly, a 2016 observational study conducted in Spain that evaluated the economic impact of NLC versus PLC in the treatment of patients with RA and AS reported that, while the costs of consultations at healthcare clinics were significantly lower with NLC versus PLC (P = 0.001), overall, there were no significant differences in total annual healthcare costs or indirect costs (work, travel, or carer-related) between the two systems [33]. Of the studies that conducted cost-effective analyses, Ndosi et al. found NLC to be cost-effective in comparison with PLC when health benefit was measured as a change from baseline in disease activity (primary endpoint; per DAS28), but not when health benefit was measured as quality-adjusted life years (QALY) [34]. However, a 24-month RCT in Denmark, in which health benefit was measured as QALY, found NLC to be cost-effective in the management of RA in comparison with both PLC and shared care (no planned nurse or rheumatologist consultations) [25].

Training and resource needs to be identified by rheumatology nurse specialists

Two articles provided considerations for training and resource needs identified by rheumatology nurse specialists (Table 1). While evidence suggests that NLC is generally associated with improved clinical and cost outcomes in the management of RA, there could be the potential to further optimize NLC by meeting additional training and resource needs identified by nurses working in rheumatology. A 2006 questionnaire administered to 95 nurse practitioners working in rheumatology departments in the UK identified the following factors that could enhance their role [29]: attendance at postgraduate courses and obtaining further qualifications; active participation in the delivery of medical education; training in practical procedures such as intra-articular injections; protected time and resources for audit and research; formal training in counseling; and implementation of nurse prescribing. Many of these factors were linked with attributes that nurses identified as being necessary for their competency (such as knowledge and understanding of rheumatic diseases and drug therapy). More recently, an extensive 2017 survey of 2338 nurse practitioners working with rheumatology patients in a primary care setting in the US identified the following resource and training needs to optimize NLC [35]: provision of an RA medication chart with indications/contraindications, adverse events, and monitoring advice to help determine the best course of treatment; an RA assessment tool for better management of patients; further education on the long-term efficacy and safety of RA medications; and access to academic conferences, events, peer-reviewed journals, and online forums or educational tools to facilitate the exchange of educational information with other HCPs.

Expert commentary: challenges around the implementation of NLC in the AfME region

An insight into the challenges facing the implementation of NLC in the AfME region was provided by the authors.

The wealth disparity across the AfME region impacts significantly on available healthcare resources, and limits opportunities for implementing and expanding multidisciplinary teams. The most recent data from the World Bank reports that health expenditure per capita, per year, ranges from US dollars (USD) 198.00 in sub-Saharan Africa to USD 1287.69 in the Middle East and North Africa [42]. With the health system chronically underfunded in numerous countries across the AfME region, there are shortages of nurses, with an unbalanced distribution between urban and rural areas. Also, negative cultural perceptions of the nursing profession, long working hours, and relatively low pay have further contributed to a nursing shortfall. As such, in areas with a limited nursing workforce, it may not be possible for nurses to focus on a single specialty. Furthermore, although recognition of nurse specialization is increasing, there remains the challenge of nurses emigrating from sub-Saharan African countries to areas where they receive greater appreciation and remuneration (author opinion).

In the opinion of the authors, NLC may be able to help overcome some of the particular challenges facing rheumatology care in the AfME region. For example, studies have shown that in Saudi Arabia and some African countries, the diagnostic delay of RA is long, between 2.5 and > 4 years [43,44,45], thereby preventing early access to treatment before irreversible joint damage. As a result, when patients are eventually diagnosed with RA, they often already have erosive disease or high disease activity. Access to NLC may relieve the burden on rheumatologists and allow quicker access to a specialist HCP. However, even after diagnosis, patients with RA are often undertreated in the region, with access to therapies dependent on the nation’s healthcare system, drug availability, and economic status [46]. Lack of access to biologic therapies has been highlighted as a particular challenge to the implementation of standardized European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) treatment guidelines in Africa [19]. At the same time, a recent study conducted in five Arab countries (Jordan, Lebanon, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and UAE) found significant differences in the use of biologic therapies between countries [47]. Patient educational deficits around the efficacy of treatments and the perception of RA as an incurable disease may also pose additional barriers to treatment acceptance. Specialized nurses with an in-depth knowledge of the available treatment pathways could enhance patient education. Furthermore, they could act as advocates for improved patient treatment and promote the wider use of more advanced therapies across the field of rheumatology (author opinion).

Expert commentary: proposed strategies for the implementation of NLC in the AfME region

The evidence discussed across each of the four key themes identified above was considered by the authors, and based on the expert knowledge of the authors, we propose a series of strategies, shown in Table 2 [48,49,50,51,52,53], for the implementation of NLC in the AfME region.

Discussion

In summary, the articles identified in this literature search provide compelling support for NLC in RA disease management. The roles of nurses in the NLC examples reviewed were varied. In addition to monitoring disease activity and treatment, NLC facilitates patient education and support, and nurses are able to coordinate multidisciplinary care. Patient perceptions of NLC are generally positive, and reported as better than or comparable with PLC, with no real patient-reported barriers to care identified.

Furthermore, there is evidence that NLC enhances clinical outcomes in patients, with most evidence focusing on disease activity (per DAS28). At the same time, from a health economics perspective, NLC is associated with better or comparable cost-effectiveness versus PLC. Finally, rheumatology nurses have important suggestions regarding the enhancement of NLC. Limitations acknowledged by the authors of the articles include the need for more data in this area from a greater number of patients, within which subgroups (for example, by disease type and activity) can be assessed over prolonged periods. Increased use of NLC could provide such data.

Overall, given the clear benefits associated with NLC, it is justified to propose strategies for the implementation of this practice in the AfME region. The evidence discussed across each of the four key themes identified above was considered by the authors and allowed the proposal of strategies for NLC programs across the AfME region.

There was no scoring system given for each author to determine the weight of each proposed strategy. Rather, the proposed strategies were collectively agreed upon using a modified Delphi technique. Overall, the proposals represent important strategies to be considered across the AfME region for the development of NLC programs. However, the value and importance of some strategies may vary by country, based on differences in their economic and educational systems. As such, it was not appropriate to assign a weight to each proposed strategy.

The findings of this narrative literature review are limited by the inclusion of articles from a small geographic area, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the application of these strategies may be limited by the legal requirements, differences in clinical practice, cost, cultural differences, and patient perception in each country. Nevertheless, these proposed strategies aim to act as a foundation for the introduction and development of NLC programs across the AfME region.

Conclusions

NLC in RA disease management has been shown to have positive impacts on patients’ perceptions of their treatment, clinical outcomes, and healthcare costs. Despite these benefits, there is a lack of rheumatology nurse specialists across AfME, a region where there is low public disease awareness and inadequate treatment for RA. The proposed strategies presented in this paper aim to act as a foundation for the development of NLC programs across the AfME region. Looking to the future, specialist nursing could move away from focusing on a specific disease, such as RA, and instead move towards working across disease taxonomies, such as immune-mediated rheumatic disorders [54]. It is the expert opinion of the authors that such a move could further enhance cost-effectiveness in training and establishing nurses to lead care in a range of clinical settings across the AfME region.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- AfME:

-

Africa and the Middle East

- AS:

-

Ankylosing spondylitis

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DAS28:

-

Disease Activity Score in 28 joints

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- EULAR:

-

European League Against Rheumatism

- HCP:

-

Healthcare professional

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- IA:

-

Inflammatory arthritis

- JIA:

-

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- LSQ:

-

Leeds Satisfaction Questionnaire

- MSK:

-

Musculoskeletal

- NLC:

-

Nurse-led care

- PLC:

-

Physician-led care

- PRO:

-

Patient-reported outcome

- PsA:

-

Psoriatic arthritis

- QALY:

-

Quality-adjusted life years

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SpA:

-

Spondyloarthritis

- UAE:

-

United Arab Emirates

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- US:

-

United States

- USD:

-

United States dollars

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Carmona L, Wolfe F, Vos T, Williams B, Gabriel S, Lassere M, Johns N, Buchbinder R, Woolf A, March L (2014) The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 73:1316–1322. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204627

Usenbo A, Kramer V, Young T, Musekiwa A (2015) Prevalence of arthritis in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 10:e0133858. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133858

Dahou-Makhloufi C, Mechid F, Benaziez R, Zehraoui N, Matari D, Haddam HT, Oussaid M, Achek M (2018) PT6C:096 Low rheumatoid arthritis prevalence in Algeria: a Mediterranean singularity? Clin Exp Rheumatol 1(Suppl 109):Abstract PT6C:096

Courage UU, Stephen DP, Lucius IC, Ani C, Oche AO, Emmanuel AI, Olufemi AO (2017) Prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases in a semi-urban Nigerian community: results of a cross-sectional survey using COPCORD methodology. Clin Rheumatol 36:2509–2516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3648-z

Al-Dalaan A, Al Ballaa S, Bahabri S, Biyari T, Al Sukait M, Mousa M (1998) The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the Qassim region of Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med 18:396–397. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.1998.396

Jamshidi AR, Tehrani Banihashemi A, Roknsharifi S, Akhlaghi M, Salimzadeh A, Davatchi F (2014) Estimating the prevalence and disease characteristics of rheumatoid arthritis in Tehran: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD study (from Iran COPCORD study, Urban Study stage 1). Med J Islam Repub Iran 28:93

Chaaya M, Slim ZN, Habib RR, Arayssi T, Dana R, Hamdan O, Assi M, Issa Z, Uthman I (2012) High burden of rheumatic diseases in Lebanon: a COPCORD study. Int J Rheum Dis 15:136–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01682.x

Battafarano DF, Ditmyer M, Bolster MB, Fitzgerald JD, Deal C, Bass AR, Molina R, Erickson AR, Hausmann JS, Klein-Gitelman M, Imundo LF, Smith BJ, Jones K, Greene K, Monrad SU (2018) 2015 American College of Rheumatology workforce study: supply and demand projections of adult rheumatology workforce, 2015–2030. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 70:617–626. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23518

Garner S, Lopatina E, Rankin JA, Marshall DA (2017) Nurse-led care for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the effect on quality of care. J Rheumatol 44:757–765. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.160535

Ndosi M, Vinall K, Hale C, Bird H, Hill J (2011) The effectiveness of nurse-led care in people with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 48:642–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.007

Houweling ST, Kleefstra N, van Hateren KJ, Kooy A, Groenier KH, Ten Vergert E, Meyboom-de Jong B, Bilo HJ, Langerhans Medical Research Group (2009) Diabetes specialist nurse as main care provider for patients with type 2 diabetes. Neth J Med 67:279–284

New JP, Mason JM, Freemantle N, Teasdale S, Wong LM, Bruce NJ, Burns JA, Gibson JM (2003) Specialist nurse-led intervention to treat and control hypertension and hyperlipidemia in diabetes (SPLINT): a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 26:2250–2255. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.8.2250

Campbell NC, Ritchie LD, Thain J, Deans HG, Rawles JM, Squair JL (1998) Secondary prevention in coronary heart disease: a randomised trial of nurse led clinics in primary care. Heart 80:447–452. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.80.5.447

Hendriks JM, de Wit R, Crijns HJ, Vrijhoef HJ, Prins MH, Pisters R, Pison LA, Blaauw Y, Tieleman RG (2012) Nurse-led care vs. usual care for patients with atrial fibrillation: results of a randomized trial of integrated chronic care vs. routine clinical care in ambulatory patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 33:2692–2699. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs071

Strömberg A, Mårtensson J, Fridlund B, Levin LA, Karlsson JE, Dahlström U (2003) Nurse-led heart failure clinics improve survival and self-care behaviour in patients with heart failure: results from a prospective, randomised trial. Eur Heart J 24:1014–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00112-x

Moore S, Corner J, Haviland J, Wells M, Salmon E, Normand C, Brada M, O'Brien M, Smith I (2002) Nurse led follow up and conventional medical follow up in management of patients with lung cancer: randomised trial. BMJ 325:1145. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7373.1145

Hooker RS (2008) The extension of rheumatology services with physician assistants and nurse practitioners. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 22:523–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2007.12.006

Bech B, Primdahl J, van Tubergen A, Voshaar M, Zangi HA, Barbosa L, Boström C, Boteva B, Carubbi F, Fayet F, Ferreira RJO, Hoeper K, Kocher A, Kukkurainen ML, Lion V, Minnock P, Moretti A, Ndosi M, Pavic Nikolic M, Schirmer M, Smucrova H, de la Torre-Aboki J, Waite-Jones J, van Eijk-Hustings Y (2020) 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the role of the nurse in the management of chronic inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 79:61–68. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215458

El Zorkany B, Alwahshi HA, Hammoudeh M, Al Emadi S, Benitha R, Al Awadhi A, Bouajina E, Laatar A, El Badawy S, Al Badi M, Al-Maini M, Al Saleh J, Alswailem R, Ally MM, Batha W, Djoudi H, El Garf A, El Hadidi K, El Marzouqi M, Hadidi M, Maharaj AB, Masri AF, Mofti A, Nahar I, Pettipher CA, Spargo CE, Emery P (2013) Suboptimal management of rheumatoid arthritis in the Middle East and Africa: could the EULAR recommendations be the start of a solution? Clin Rheumatol 32:151–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-012-2153-7

Halabi H, Alarfaj A, Alawneh K, Alballa S, Alsaeid K, Badsha H, Benitha R, Bouajina E, Al Emadi S, El Garf A, El Hadidi K, Laatar A, Makhloufi CD, Masri AF, Menassa J, Al Shaikh A, Swailem RA, Dougados M (2015) Challenges and opportunities in the early diagnosis and optimal management of rheumatoid arthritis in Africa and the Middle East. Int J Rheum Dis 18:268–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.12320

Kalla AA, Tikly M (2003) Rheumatoid arthritis in the developing world. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 17:863–875

Kumar B (2017) Global health inequities in rheumatology. Rheumatology (Oxford) 56:4–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kew064

World Health Organization (2020) Global Health Observatory (GHO) data. Density of nursing and midwifery personnel (total number per 10 000 population, latest available year). https://www.who.int/gho/health_workforce/nursing_midwifery_density/en/. Accessed 04 Aug 2020

Primdahl J, Sørensen J, Horn HC, Petersen R, Hørslev-Petersen K (2014) Shared care or nursing consultations as an alternative to rheumatologist follow-up for rheumatoid arthritis outpatients with low disease activity-patient outcomes from a 2-year, randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 73:357–364. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202695

Sørensen J, Primdahl J, Horn HC, Hørslev-Petersen K (2015) Shared care or nurse consultations as an alternative to rheumatologist follow-up for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) outpatients with stable low disease-activity RA: cost-effectiveness based on a 2-year randomized trial. Scand J Rheumatol 44:13–21. https://doi.org/10.3109/03009742.2014.928945

Arvidsson SB, Petersson A, Nilsson I, Andersson B, Arvidsson BI, Petersson IF, Fridlund B (2006) A nurse-led rheumatology clinic's impact on empowering patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Nurs Health Sci 8:133–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2006.00269.x

Bala SV, Samuelson K, Hagell P, Svensson B, Fridlund B, Hesselgard K (2012) The experience of care at nurse-led rheumatology clinics. Musculoskeletal Care 10:202–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1021

de Thurah A, Esbensen BA, Roelsgaard IK, Frandsen TF, Primdahl J (2017) Efficacy of embedded nurse-led versus conventional physician-led follow-up in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. RMD Open 3:e000481. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000481

Goh L, Samanta J, Samanta A (2006) Rheumatology nurse practitioners' perceptions of their role. Musculoskeletal Care 4:88–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.81

Koksvik HS, Hagen KB, Rødevand E, Mowinckel P, Kvien TK, Zangi HA (2013) Patient satisfaction with nursing consultations in a rheumatology outpatient clinic: a 21-month randomised controlled trial in patients with inflammatory arthritides. Ann Rheum Dis 72:836–843. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202296

Larsson I, Fridlund B, Arvidsson B, Teleman A, Bergman S (2014) Randomized controlled trial of a nurse-led rheumatology clinic for monitoring biological therapy. J Adv Nurs 70:164–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12183

Larsson I, Fridlund B, Arvidsson B, Teleman A, Svedberg P, Bergman S (2015) A nurse-led rheumatology clinic versus rheumatologist-led clinic in the monitoring of patients with chronic inflammatory arthritis undergoing biological therapy: a cost comparison study in a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 16:354. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0817-6

Muñoz-Fernández S, Aguilar MD, Rodríguez A, Almodóvar R, Cano-García L, Gracia LA, Román-Ivorra JA, Rodríguez JR, Navío T, Lázaro P, Group SW (2016) Evaluation of the impact of nursing clinics in the rheumatology services. Rheumatol Int 36:1309–1317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-016-3518-z

Ndosi M, Lewis M, Hale C, Quinn H, Ryan S, Emery P, Bird H, Hill J (2014) The outcome and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care in people with rheumatoid arthritis: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 73:1975–1982. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203403

Riley L, Harris C, McKay M, Gondran SE, DeCola P, Soonasra A (2017) The role of nurse practitioners in delivering rheumatology care and services: results of a U.S. survey. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 29:673–681. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12525

Sjö AS, Bergsten U (2018) Patients' experiences of frequent encounters with a rheumatology nurse-A tight control study including patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Musculoskeletal Care 16:305–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1348

Solomon DH, Fraenkel L, Lu B, Brown E, Tsao P, Losina E, Katz JN, Bitton A (2015) Comparison of care provided in practices with nurse practitioners and physician assistants versus subspecialist physicians only: a cohort study of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 67:1664–1670. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22643

Vinall-Collier K, Madill A, Firth J (2016) A multi-centre study of interactional style in nurse specialist- and physician-led rheumatology clinics in the UK. Int J Nurs Stud 59:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.02.009

Wang J, Zou X, Cong L, Liu H (2018) Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial comparing with rheumatologist-led care. Int J Nurs Pract 24:e12605. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12605

Hill J, Thorpe R, Bird H (2013) Outcomes for patients with RA: a rheumatology nurse practitioner clinic compared to standard outpatient care. Musculoskeletal Care 1:5–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.35

Primdahl J, Wagner L, Holst R et al (2012) The impact on self-efficacy of different types of follow-up care and disease status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis–a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns 88:121–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.01.012

The World Bank (2016) Current health expenditure per capita (current US$). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.PC.CD. Accessed 06 June 2019

Hussain W, Noorwali A, Janoudi N, Baamer M, Kebbi L, Mansafi H, Ibrahim A, Gohary S, Minguet J, Almoallim H (2016) From symptoms to diagnosis: an observational study of the journey of rheumatoid arthritis patients in Saudi Arabia. Oman Med J 31:29–34. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2016.06

Adelowo OO, Ojo O, Oduenyi I, Okwara CC (2010) Rheumatoid arthritis among Nigerians: the first 200 patients from a rheumatology clinic. Clin Rheumatol 29:593–597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-009-1355-0

Ndongo S, Lekpa FK, Ka MM, Ndiaye N, Diop TM (2009) Presentation and severity of rheumatoid arthritis at diagnosis in Senegal. Rheumatology (Oxford) 48:1111–1113. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kep178

Al Maini M, Adelowo F, Al Saleh J, Al Weshahi Y, Burmester GR, Cutolo M, Flood J, March L, McDonald-Blumer H, Pile K, Pineda C, Thorne C, Kvien TK (2015) The global challenges and opportunities in the practice of rheumatology: white paper by the World Forum on Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases. Clin Rheumatol 34:819–829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-014-2841-6

Dargham SR, Zahirovic S, Hammoudeh M, Al Emadi S, Masri BK, Halabi H, Badsha H, Uthman I, Mahfoud ZR, Ashour H, Gad El Haq W, Bayoumy K, Kapiri M, Saxena R, Plenge RM, Kazkaz L, Arayssi T (2018) Epidemiology and treatment patterns of rheumatoid arthritis in a large cohort of Arab patients. PLoS One 13:e0208240. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208240

Hibbert D, Al-Sanea NA, Balens JA (2012) Perspectives on specialist nursing in Saudi Arabia: a national model for success. Ann Saudi Med 32:78–85. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2012.78

Gormley GJ, Steele WK, Gilliland A, Leggett P, Wright GD, Bell AL, Matthews C, Meenagh G, Wylie E, Mulligan R, Stevenson M, O'Reilly D, Taggart AJ (2003) Can diagnostic triage by general practitioners or rheumatology nurses improve the positive predictive value of referrals to early arthritis clinics? Rheumatology (Oxford) 42:763–768. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keg213

Beattie KA, MacIntyre NJ, Cividino A (2012) Screening for signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis by family physicians and nurse practitioners using the Gait, Arms, Legs, and Spine musculoskeletal examination. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 64:1923–1927. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21740

Almoallim H, Janoudi N, Attar SM, Garout M, Algohary S, Siddiqui MI, Alosaimi H, Ibrahim A, Badokhon A, Algasemi Z (2017) Determining early referral criteria for patients with suspected inflammatory arthritis presenting to primary care physicians: a cross-sectional study. Open Access Rheumatol 9:81–90. https://doi.org/10.2147/OARRR.S134780

Almoallim H, Attar S, Jannoudi N, Al-Nakshabandi N, Eldeek B, Fathaddien O, Halabi H (2012) Sensitivity of standardised musculoskeletal examination of the hand and wrist joints in detecting arthritis in comparison to ultrasound findings in patients attending rheumatology clinics. Clin Rheumatol 31:1309–1317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-012-2013-5

Almoallim HM, Alharbi LA (2014) Rheumatoid arthritis in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 35:1442–1454

Hofmann-Apitius M, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Chamberlain C, McHale D (2015) Towards the taxonomy of human disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 14:75–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd4537

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support, under the guidance of the authors, was provided by Kirsten Woollcott, MSc, CMC Connect, McCann Health Medical Communications and was funded by Pfizer Inc, New York, NY, USA in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2015; 163: 461–464). CDB and KR are supported by the NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Birmingham.

Funding

This work was sponsored by Pfizer Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in the conception and development of this review. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final draft prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

IU has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Janssen, Newbridge, and Pfizer Inc. HA has received research grants from AbbVie and Pfizer Inc, and honoraria/speaker fees from Lilly, Novartis, and Pfizer Inc. BM has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bikma, Janssen, Novartis, and Pfizer Inc. YED and NS are employees and shareholders of Pfizer Inc. KR has received honoraria/speaker fees from AbbVie, BMS, Janssen, Lilly, Pfizer Inc, Sanofi, and UCB; and research grants from Pfizer Inc. KK has received speaker fees from Pfizer Inc. IL is an advisory board member of Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer Inc, and Roche. CDB, CDM, HASH, NT, and OA declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Uthman, I., Almoallim, H., Buckley, C.D. et al. Nurse-led care for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the global literature and proposed strategies for implementation in Africa and the Middle East. Rheumatol Int 41, 529–542 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04682-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04682-6